Introduction

The Programmatic Action Framework (PAF) introduced programmatic groups and their policy programmes into policy process research (Bandelow et al., Reference Bandelow, Hornung and Smyrl2020; Hassenteufel and Genieys Reference Hassenteufel and Genieys2020). Programmatic groups are defined as social groups of individuals within the state that form on the basis of shared biographic experiences and create a social group identity by committing to a policy programme. Policy programmes are defined as sets of policy goals and related instruments based on an inherent problem perception and resulting structural solutions that, for several decades, may shape a sector’s policies (Nyby et al. Reference Nyby, Nygård and Blum2018). More specifically, PAF postulates that the career aspirations of actors who are directly involved in the policy-making process can matter in the promotion and persistence of policy programmes, based on the premise that policy actors strive to enhance authority and expect occupational benefits and normative returns from pursuing policy ideas (Dolan Reference Dolan2000). Previous applications of the PAF and evidence for its hypotheses concern health policy (Genieys and Smyrl Reference Genieys and Smyrl2008), labour market policy (Bandelow and Hornung Reference Bandelow and Hornung2019) and defence policy (Faure Reference Faure2020).

While the PAF explanation for policy change rests on programmatic groups that pursue a joint policy programme out of career-related and normative reasons, it has so far not explicitly addressed the question of how long-term dominance of a policy programme (policy stability) and its eventual decline can be explained. Applying the PAF, we argue that the hypothesis of programmatic groups promoting programmes to advance their careers suggests that the variations in programmes closely tracks proponents’ career trajectory. PAF may thereby answer the question of how programmatic dominance, despite usually change-inducing developments, can be explained and what PAF adds to the understanding of the rise and decline of policy programmes. Against the backdrop of the hypotheses that programmatic groups and policy programmes institutionalize themselves out of strategic career interests and that greater inclusiveness of the programmatic group and its programme leads to long-term programmatic dominance, the PAF presents an endogenous explanation for policy stability.

The role of actors – or agency – and especially their careers and biographies in long-term phases of policy change and stability is yet undertheorized (May and Jochim Reference May and Jochim2013, 446). While the established perspectives inherently capture a dynamic of alternating phases of policy stability and change over time (Capano and Howlett Reference Capano, Howlett, Capano and Howlett2009), the foci of interests differ. Perspectives on policy stability identify stabilizing determinants of path dependence and preshaped trajectories for incremental change through feedback effects as well as critical junctures at which departing from this path would lead to major change (Koning Reference Koning2016; Mettler and Sorelle Reference Mettler, Sorelle, Weible and Sabatier2017; Béland and Schlager Reference Béland and Schlager2019; Hogan Reference Hogan2019). However, they do not explicitly address a continuous major change in a certain programmatic direction. By contrast, theories of policy change shed light on how external perturbations (crises, societal developments and the like), policy actors (individual or collective) and learning affect major policy change (Zafonte and Sabatier Reference Zafonte and Sabatier1998; Herweg et al. Reference Herweg, Zahariadis, Zohlnhöfer, Weible and Sabatier2017; Weible and Sabatier Reference Weible and Sabatier2017). So far, these neglect the importance of shared biographical and career-related trajectories and interests in explaining the rise and decline of policy programmes.

The upcoming section reviews existing theories of policy change and stability to emphasize the peculiarities of the PAF perspective with a focus on its contribution to understanding cyclical patterns of programmatic dominance. Based on this, the third section conceptualizes programmatic groups and policy programmes in order to substantiate testable hypotheses on the interrelation of programme characteristics, actor characteristics and programmatic dominance. The case study of German health policy from 1992 to 2011 constitutes an empirical anchor for the argument that the rise and decline of a policy programme followed a pattern of economic cycles. A final conclusion summarizes avenues for future research and discusses the scope and limitations of PAF.

Policy process theories of change and stability

Structuralist perspectives on the policy process generally have a larger focus on institutions blocking major change instead of investigating the factors that actively bring about change, such as actor networks. Regarding stability, prominent literature on path dependency has taught us that, in specific situations, altering existing structures is as costly as time-consuming and thus policy-makers stick to the status quo (Wilsford Reference Wilsford1994; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2001; Thelen Reference Thelen, Rueschemeyer and Mahoney2003) or that policy-making takes place incrementally in its regular venues, with the usual types of actors involved, and a dominant policy image shaping actors’ perceptions of problems and appropriate solutions, termed as “negative feedback” (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Breunig, Green-Pedersen, Jones, Mortensen, Nuytemans and Walgrave2009; Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Weible and Sabatier2017). Previous policies thereby shape trajectories for subsequent policy decisions, which are known under the term “policy feedback.” Actors can challenge and depart from these trajectories, though (Béland Reference Béland2010, 575). Tying in with this discussion, the PAF focuses on long-term persistence and institutionalization of a policy programme and theoretically links it to actor groups.

Turning to the factors that interrupt the stability and enable major policy change in structuralist and institutionalist theories, policy termination literature takes into account institutional opportunities and constraints for the dismantling of policies and refers to external influences like permanent austerity or crises in creating the desire for policy dismantling (deLeon Reference deLeon2007; Jordan et al. Reference Jordan, Bauer and Green-Pedersen2013; Pollex and Lenschow Reference Pollex and Lenschow2019). Bauer and Knill (Reference Bauer and Knill2014) assume that policy actors act rationally according to cost–benefit analyses and particularly the goal of electoral success when dismantling and terminating policies. Additionally, the notion of critical junctures refers to the identification of instances when there is a chance for policy termination and major policy change beyond incremental change (Hogan Reference Hogan2019; Rinscheid et al. Reference Rinscheid, Eberlein, Emmenegger and Schneider2019). In accounting for both exogenous and endogenous triggers for critical junctures, incrementalists have centred on the concept of actors inherent particularly in ideational institutionalism to assess in what way and under what circumstances actors alter institutions and policies (Koning Reference Koning2016). Then, change is often ascribed to different factors such as policy networks resolving policy failures (Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Skogstad and Atkinson1996) or narratives of crisis impacts that prompt a new, fitting policy paradigm (Oliver and Pemberton Reference Oliver and Pemberton2004; Kern et al. Reference Kern, Kuzemko and Mitchell2014). In the view of Hacker and Pierson (Reference Hacker and Pierson2014), actor groups strategically act in the policy process to fight for authority and, when succeeding in this struggle, are rewarded with the ability to shape governance and policies. In policy regime perspectives, regime durability then follows from changes in the composition of political power and interests, declining support among the coalition that braces the regime or certain partisan coalitions that benefit from maintaining support for a policy regime (Jochim and May Reference Jochim and May2010, 320).

Actor-centred perspectives on policy change and stability bring in different lenses on the linkage between actors and ideas. A first look is devoted to policy communities, policy networks, issue networks and epistemic communities. While policy networks encompass different types of networks that are characterized by different degrees of close and coordinated cooperation and different scopes of actor inclusion (Döhler Reference Döhler, Marin and Mayntz1991; Jordan and Schubert Reference Jordan and Schubert1992), policy communities, issue networks and epistemic communities each present a specific type of network, distinguished by the number of actors, homogeneity, variety of interests, agreement on policy goals, transnationality, sector specificity, resources and power positions (Marsh and Rhodes Reference Marsh, Rhodes, David and Rhodes1992; Dunlop Reference Dunlop2009; Mavrot and Sager Reference Mavrot and Sager2018; Elander and Gustavsson Reference Elander and Gustavsson2019). Yet these types of networks are rarely bound to a subsystem and therefore can hardly promote a sectoral policy programme that, over a longer period of time, dominates sectoral policy. Moreover, they neither include shared biographies, nor a career interest in the group’s members. The differences between programmatic groups and other network types are detailed in Table 1.

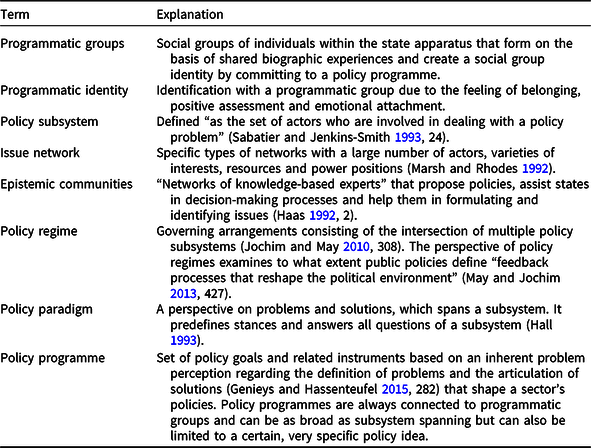

Table 1. Explanation and distinction of subject-specific terms

Why do actors promote certain content? The Advocacy Coalition Framework (ACF) sees shared beliefs as the driving factor of cooperation (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith Reference Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith1993; Weible and Ingold Reference Weible and Ingold2018). However, ACF studies suggest that trust and resources are sometimes more and sometimes less important for cooperation than shared beliefs (Matti and Sandström Reference Matti and Sandström2011; Calanni et al. Reference Calanni, Siddiki, Weible and Leach2014; Fischer et al. Reference Fischer, Ingold, Sciarini and Varone2016; Weible et al. Reference Weible, Heikkila and Pierce2018). The Multiple Streams Framework (MSF) (Herweg et al. Reference Herweg, Zahariadis, Zohlnhöfer, Weible and Sabatier2017; Sager and Thomann Reference Sager and Thomann2017) primarily refers to situational explanations for explaining change; stability here just results from the absence of policy windows and/or adequate strategies of entrepreneurs. Moreover, a policy entrepreneur pushing a policy proposal out of strategic self-interest does so in an ambiguous environment that does not actively promote her/his pet policy but grants it (Zahariadis Reference Zahariadis, Sabatier and Weible2014; Herweg et al. Reference Herweg, Huß and Zohlnhöfer2015; Béland and Howlett Reference Béland and Howlett2016).

Summarizing this section, what PAF adds to the presented theoretical lenses is a European perspective on policy change and stability that assumes biographical intersections and resulting trust as the root for collective action and a career-related promotion of policy programmes within a policy subsystem as an explanation for programmatic dominance. PAF’s main focus lies on the long-term role of actors in key positions whose career is connected to the success of a policy programme. The PAF is thereby distinct from existing theoretical perspectives both with regard to the theoretical mechanisms linking actors and policy change and with regard to terminology and term definitions. These have been reviewed above and compiled in an overview presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 2. Comparison of theoretical approaches in relation to the PAF

Source: Weible and Sabatier Reference Weible and Sabatier2017, own compilation.

Programmatic groups and policy programme cycles

PAF starts from the idea that policy programmes are associated with programmatic groups and that this view can explain long-term policy persistence because it enables a focus on programme- and actor-related characteristics that, in combination, explain policy programme persistence in its dynamic of alternating policy change and stability. It understands programmatic groups as composing actors with direct influence in the policy process and particularly on policy content who ally out of strategic reasons to push their individual careers and influence within the subsystem. A programmatic group adopts a policy programme that functions both as a binding element of the programmatic group and as a means of leverage to realize the common goal of increased authority. The term programmatic group denotes an irrevocable tie between a policy programme and a programmatic group that is committed to this programme. Such group membership then builds the basis for mutual trust and collaboration (Tanis and Postmes Reference Tanis and Postmes2005; Stern and Coleman Reference Stern and Coleman2015). We build upon these factors that enable long-term stability of the policy programme and thus explain policy persistence over career cycles. The end of a policy program is determined by the observation that no programmatic actors of the policy program can be found in the identified key positions.

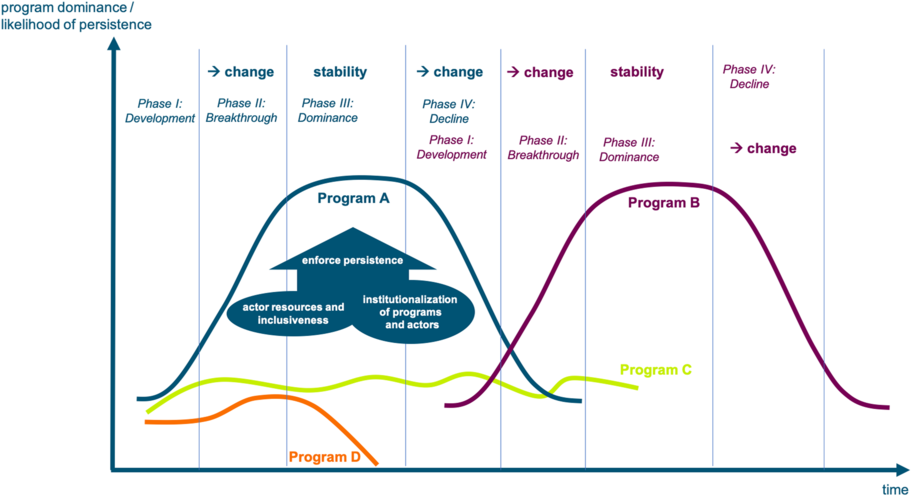

From this argument, one can derive the assumption that policy programmes follow a pattern of cycles. The mechanism behind this pattern is a logical array of developments within a policy subsystem. It proceeds from the basic assumptions that (1) in political systems, there are limited positions of power which are central in decision-making processes and that (2) actors in policy subsystems strive to maximize their influence and authority by occupying these positions. It can be hypothesized that there are different phases of a programmatic “cycle,” which determine the likelihood of a policy programme’s persistence. Figure 1 depicts this cyclical pattern that is accordingly formulated as the programme cycle hypothesis.

Figure 1. Policy programme cycles. Source: Own depiction of ideal types of phases that policy programmes run through (cyclical pattern), X axis presents time (in years) and Y axis presents the dominance of a programme that is connected to the likelihood of persistence.

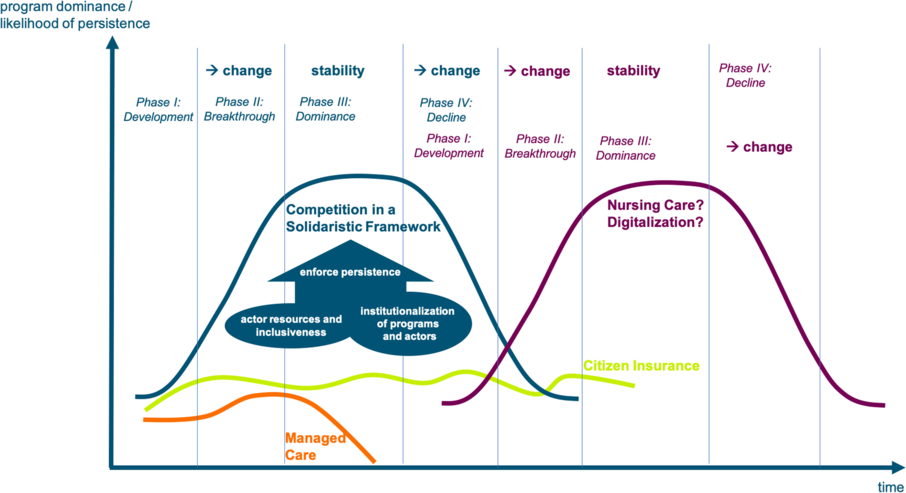

Figure 2. Empirical illustration of the case study according to theoretical considerations. Source: Own depiction based on interviews with programmatic actors that have promoted or still promote these programmes (at least one interviewee per programme).

Phase I: The programmatic group forms and develops a joint policy programme. This policy programme is not a result of shared ideology, beliefs or other types of value-based preferences but rather serves as an instrument to enter the struggle over authority in the sector. Central to the programmatic group’s motive is to make the policy programme succeed in order for the programmatic group to place itself in top-level positions that assert dominance within a policy subsystem. Phase I, the development phase, is a phase that is independent of other existent programmes in other phases and is always possible to run through by policy programmes and programmatic groups. The existence of other parallel programmes is possible but since policy programmes in PAF logic are connected to groups, these parallel programmes are competitive policy programmes and therefore not used by newly forming programmatic groups. It is however possible for an emerging programmatic group to take an existing policy programme as inspiration for the development of its own programme and only introduce some amendments that should help the programme’s success. Some programmes might never pass the preparation phase (see programme C in Figure 1) because the programmatic groups are too weak; the policy programme does not fulfill the criteria of success (programme coherence, programme correlation to the national mood and response to emerging challenges), or the programmatic group has chosen the wrong point in time for an attempt to breakthrough – meaning they challenged the ruling group in their phase of dominance.

Phase II: At a given point in time, a policy programme is likely to succeed and establish itself as the dominant policy programme in a given sector. This is particularly likely if either there is no current dominant policy programme so that the programmatic group only needs to prevail over programmatic groups at the same stage of development. Or, a policy programme may substitute a previously dominant policy programme. However, this is much more likely when the previously dominant programme has already entered the phase of decline and least likely when it is on the way to or at the top of its phase of dominance. In those cases, policy programme persistence and consequent stability are highest. If a policy programme breaks through, by definition, the actors who are connected to the programme come out on top, too.

Phase III: As a consequence of breakthrough, the programme gains popularity among those actors in the subsystem that feel they can equally profit from the dominant programme by engaging in it and thus gaining remaining posts in power. With a rising number of proponents of the programme, the programmatic group prospers and its power increases correspondingly. Top positions are occupied by the dominant programmatic group and the policy programme enjoys support among both officials and the public, who are climbing career ladders by joining the programmatic group and supporting the policy programme. This is the phase in which the policy programme and the programmatic group are strongest and hardest to tackle. While single policies of e.g. single-policy entrepreneurs have a chance to be adopted, provided that they fit the dominant policy programme, policy programmes that are different from the dominant policy programme almost necessarily fail as long as they do not present a group as strong and a programme as successful as the dominant one – which is almost impossible given that the dominant group already pervades the top positions. In this phase, there is programme stability, which does not mean that there are no new policies adopted, only that policy change occurs within the boundaries of the policy program’s overall vision. Usually, the dominant programme is implemented step by step in this phase, meaning that one policy after another is adopted in the attempt to realize the entire policy programme over a long period of time and in every corner of a subsystem because adopting an encompassing policy reform that depicts all elements of the policy programme would be hard to realize and push through at once.

Phase IV: At one point in time, when the programmatic group’s resources in terms of power positions and influence diminish, internal competition within the programmatic group over remaining resources arises. Resources diminish when the programmatic group’s members leave office due to retirement or change in positions or are being replaced due to e.g. scandals or when the policy programme does not manage to adapt to emerging national challenges and present adequate measures to solve them. At this point, the policy programme and the associated programmatic group become less attractive to outsiders, as there is less to be compared to the alternative of turning to a new programmatic group with a new policy programme. Yet, the remaining individual actors in the policy subsystem equally strive towards increased authority in the sector and thus tend to orientate themselves to a different programmatic group with a different policy programme to be able to challenge the dominant one. The dominant programmatic group and the associated programme lose supporters and, with them, authority. In addition to that, while they had once represented innovation and change, they only represent stagnation at that point because the ideas and individuals have aged. Briefly speaking, once the policy programme and programmatic group in power have transcended the zenith of power, the likelihood increases that other programmatic groups and their policy programmes are successful. This leads to a new hypothesis to be added to the existing PAF:

Programme Cycle Hypothesis: A policy programme’s persistence runs through a cyclical pattern, during which the likelihood of policy persistence depends on the phase in which the policy programme finds itself at a given point in time.

Figure 1 presents an ideal-typical illustration of the four phases of programme dominance (programme A) and the hypotheses. It visualizes how a policy programme (A) becomes successful, stays dominant for a certain amount of time and later declines. At the same time, it exemplifies the relation to other policy programmes: Parallel to policy programme dominance, there may be other policy programmes and programmatic actors striving to break through and become dominant. They will not succeed as long as the policy programme is at the peak of dominance because the power positions are occupied by the members of the dominant programmatic group, and other actors might have an interest in joining an emerging programme but not (yet) have the resources to make it succeed. An emerging programme, therefore, may only trigger the decline of a dominant programme if it manages to win over members of the other programmatic group, which is, in fact, only possible when the strong social identification of these programmatic actors with the policy programme is not damaged (e.g. by combining two policy programmes or providing a stronger social identification). The unsuccessful programmatic groups may either dissolve (programme D) or live on and wait for their time to come (programme C). After the programme cycle has ended, a new policy programme may take its place (programme B).

Drawing more explicitly on the theoretical overview presented in the preceding section and the foundations of the PAF, we can formulate hypotheses on the persistence of policy programmes and connected programmatic groups to account for policy stability. The hypotheses are best tested within a qualitative research design, preferably interviews, as shown in the later empirical case study. The degree of institutionalization of the programme and programmatic actors and the programmatic group’s inclusiveness emerge as potentially enforcing factors for policy programme resilience both from existing literature and the insights from interviews that are later presented in the empirical case study. Path dependence displays as a further potential mechanism on stability, the power constellations of actors when institutions evolve (Thelen Reference Thelen, Rueschemeyer and Mahoney2003; Beyer Reference Beyer2010). Thus, actors’ institutionalization presents a determinant of stability because “an institution may persist even when most rational individuals prefer to change it, provided that a powerful elite that benefits from the existing arrangement has sufficient strength to resist its transformation” (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2001). A powerful programmatic group and programmatic dominance are reinforced by the institutions that are created, because these institutions privilege the powerful programmatic group in distributing authority and, in turn, the powerful programmatic group again reinforces the institutions that present the path-dependent settings to support the policy programme by installing its members in the respective institutions (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2001).

As with “a dominant political coalition successfully fending off all attempts by minorities to alter the political course” (Peters et al. Reference Peters2005, 1278), a programmatic group similarly attempts to produce path dependencies that guarantee its dominance. Path dependence is ensured by establishing new institutions connected to the policy programme and by providing a discourse around the policy programme that is shared by as many policy actors and the public as possible. Thus, a high degree of institutionalization generates more of such positions at the top level and thus an increased number of supporters who secure the policy program’s support. Furthermore, institutionalization becomes a process with its own dynamics, as newly created institutions strive towards their self-enhancement (Pierson Reference Pierson2002). This leads to the following hypothesis.

Programme and Programmatic Actor Institutionalization Hypothesis: A policy programme is more likely to persist and persist over a longer period of time, the more institutions sustain its dominance through programmatic actors occupying these positions and the greater the authority these institutions and actor groups possess.

Especially in consensus democracies the homogeneity of programmatic actors can become a problem as successful programmatic groups need support from different political parties and different potential veto points (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002; Zohlnhöfer Reference Zohlnhöfer2009). Even if programmatic groups, whose members do not have a pluralistic background, gain power, they will not be able to implement their programme and, therefore, soon lose power. If the programmatic group exerts influence at many and various power positions in a sector, it can cushion changes in power relations that might lead to some actors being replaced as those newly elected take their place. As a consequence, a programmatic group – and the associated policy programme – are more likely to stay successful the broader and more various power positions it occupies, as the Actor Pluralism Hypothesis states.

Actor Pluralism Hypothesis: A policy programme is more likely to persist and persist over a longer period of time, the higher the variety and the wider the breadth of power positions that the individual members of the programmatic group occupy.

Despite the need for the breadth of power positions to be successful, a programmatic group continues to base on homogenous and commonly shared experiences of its programmatic actors. Among these are repeated instances of collaboration, in organizations, committees or similar types of bodies that are concerned with intellectual thinking and decision-making. Only then it is possible for them to develop a feeling of belonging, positive evaluation, and emotional attachment to what emerges as a social group of actors that can later turn into a programmatic group when committing to a jointly shared and supported policy programme. The policy programme thereby can be based on their previous work, which normally resembles their way of thinking and preferences. Nevertheless, these preferences are supposed to be much less stable than it is the case with the ACF and core beliefs or perspectives of rationality that presume stable and certain preferences but much more pronounced than in ambiguous environments that form the basis of the MSF. More important for success is the extent to which individual members of social groups exhibit group loyalty. A higher degree of group loyalty and strong identification of members at the various power positions ensures long-term support of the group throughout the policy process, but a strong identification regarding e.g. political parties easily leads to strong polarization (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015), which leaves programmatic groups with the challenge of decreasing potential polarization while keeping group loyalty and identification high. Therefore, the inclusion of leading figures of the party competition in democracies can have a negative impact as these polarizing people prevent actors from joining the group. Consequently, programmatic success is more likely when the programmatic group manages to be inclusive, without putting prominent, polarizing figures centre-stage in group representation.

Actor Inclusiveness Hypothesis: A policy programme is more likely to persist and persist over a longer period of time if the programmatic group attached to it is not primarily associated with prominent figures of partisan competition.

Empirical illustration from German health policy: Competition in a Solidaristic Framework

To illustrate the empirical relevance of the theoretical argument presented in this article, this section takes German health policy as an example. The selection of this case is made considering the case as a deviant one with regard to existing theoretical approaches and thereby checking an alternative explanation for the outcome (policy change) (Seawright and Gerring 2007, 297). Regarding the validity of the findings that support the formulated theoretical claims, the case study rests on the assumption of process tracing that the evidence supporting the theoretical explanation is most trusted when alternative explanations fall short in explaining the process (Bennett and Elman Reference Bennett and Elman2006, 460). Further cross-case studies then are to confirm the explanatory power of PAF. German health policy fulfills both the criteria of being largely independent of changes in government, with a strong self-governance and a range of decision-makers not reshuffled through elections, and of a sector close to the state, with the statutory health insurance (SHI), state oversight on hospitals and the self-governance as a mediate public administration, among other characteristics. Furthermore, German health policy is a sector that must repeatedly deal with emerging challenges, complex actor constellations and different policy ideas that fight over getting a hearing. German health policy is an exciting case study for observing the relation between innovative programmatic groups and programmatic gridlock. Previous literature indicates a paradox at this point. On the one side, analyses depict substantial changes through a programmatic elite that encouraged a systematic restructuring of the health system in the last quarter-century (Knieps Reference Knieps2015; Busse et al. Reference Busse, Blümel, Knieps and Bärnighausen2017; Hornung and Bandelow Reference Hornung and Bandelow2018). On the other side, there is the observation that fundamental reforms were not realized, although a broad political majority supports them. How can we explain this apparent contradiction between reform realization and blockades, with an ongoing realization of specifically directed reforms? The established perspectives of policy research do not provide an adequate answer to this question, as neither systematic policy core beliefs of a dominant coalition nor single political entrepreneurs or situational aspects nor persuading narratives or systematic interests of corporative actors explain the two sides of reform success and failure. The empirical illustration of programme conjunctures presented here for German health policy, in fact, shows the change in strategies of an identifiable programmatic group towards specific policies, dependent on the direct relation of the programmatic group to its own policy programme. The empirical data supporting this argument were gathered during research projects on German health policy and stemmed from repeated interviews with high-ranking officials and actors in key positions as well as outsiders. In sum, the data include some 20 of those in-depth interviews.

Phase I: Enquete Commission

German health policy had experienced fundamental blockades of structural reform that resulted from the institutional conditions of the German consensus democracy (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012) and the contradictory substantial policy goals of the involved actors. The evolution of the first programmatic group in German health policy at the end of the 1980s presented a precondition for surmounting these blockades and for realizing in several steps a reform programme called “Competition in a Solidaristic Framework” (Knieps 2017). This programmatic group comprised actors from different areas of the state (government, parliament, self-governance, sickness fund associations) and different parties, all of them having divergent ideological orientations. The origins of both the programmatic group and the policy programme can be traced back to the Enquete Commission “Structural Reform of the Statutory Health Insurance” from 1987 to 1990. The final report of this Commission already included a number of reform proposals that were adopted during the subsequent 20 years, and the members of the Commission achieved central power positions in establishing this programme. Interviews with these actors have confirmed that many ideas from this Commission were later translated into policy and that the actors mutually helped each other to enter higher policy positions in administration and self-governance.

Phase II: a cross-partisan compromise and the German Health Care Structure Act 1992

The breakthrough phase found expression in the preparation of the first structural reform on the basis of the policy programme from 1990 to 1992. In these years, the programmatic actors that were bound by their biographical intersection of the Enquete Commission attracted other programmatic actors that joined the group and were equally biographically bound to existing members of the group. While the core of this group consisted primarily of bureaucrats that occupied central positions in the health ministry, such as heads of divisions and departments (e.g. Franz Knieps, Manfred Lang, Ulrich Tilly), the group also encompassed central figures of the self-governance (like Wolfgang Kaesbach, Christopher Herrmann) (actor pluralism). With these varieties of resources coming from central positions in the health sectors without being subject to partisan competition (programmatic actors partly had partisan affiliations, which however did not play a central role, as one interview partner emphasizes), the programmatic group was able to realize the adoption of its first step in the policy programme: the Health Care Structure Act 1992. At this point, the partisan competition only became relevant in the sense that the programmatic group needed to get the partisan decision-makers of government on board. For this undertaking, it was necessary that the programme provided a vision that multiple political camps could likewise identify with. The Lahnstein compromise – named according to the place where the reform was negotiated between party representatives and programmatic actors – finally resulted in the reform proposal that was later approved by the parliament, thanks to the preparation of the programmatic actors in cooperation with the governing majority. The strategic alliances formed with multiple actors in key positions thereby enabled to pass the reform, also because the content was not considered as a “pet policy” of outstanding figures of partisan competition ( actor inclusiveness ).

Phase III: competition in a Solidaristic Framework from 1992 to 2011

The phase of stability finally ranged from 1992 to 2011. In this period, several also major policy reforms were adopted that are in line with the overall vision of the policy programme “Competition in a Solidaristic Framework.” Consequently, the policies introduced elements of competition in the health care sector, starting from the competition between sickness funds that were enhanced by the Health Care Structure Act 1992 and proceeding with the Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) Modernization Act 2003 that further strengthened this competition e.g. by selective contracts with ambulatory health care suppliers and implemented the Joint Federal Committee (JFC) as the central body of decision-making. The 2007 reform was even labelled the Act to Enhance Competition in the Statutory Health Insurance (SHI) and also established a new institution, the health care fund, that since then has occupied the important role of collecting wage-related contributions of all insured citizens independent of the sickness funds and then reallocates these funds to the sickness funds by also complying with a risk compensation scheme. This has also led to the creation of new jobs, for example, in the now Federal Agency for Social Security (Bundesamt für Soziale Sicherung, BAS). Connected to the vision of competition, there is an increasing amount of scientific reports on the arrangement, procedure and effects of competition in the health care system. As a result, many scientific advisors that belong to the programmatic group since its beginnings now profit from the programme in the sense that they cover advisory positions close to the state with significant influence in the policy process, where they continuously spread the idea of competition ( programme and actor institutionalization ). The final reform that finalized the vision of increased competition in the health care sector was the Pharmaceutical Market Restructuring Act (Arzneimittelmarktneuordnungsgesetz, AMNOG). It made an additional benefit assessment for the introduction of new medical products into the market obligatory and only then allowed the companies to enter price negotiations. If no additional benefit can be documented, the product is automatically priced according to the reference pricing system. This again led to new jobs and the creation of the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen, IQWIG) ( programme and actor institutionalization ).

Although the programmatic group once started as a great reformer to effect substantial changes in the health system, it fended off other reform proposals in this phase. For instance, a group concerned with managed care, which picked up on the problem of a strong separation between the sectors of inpatient and outpatient care, was formed and tried to gain influence in the system. Some elements of managed care were indeed compatible with the programme of the dominant programmatic group. Hence, these were partly integrated into the policy programme, such as medical service centres, which were originally called polyclinics, later health centres and finally found the narrative of medical service centres that fit into the programme. Managed care as a fixed term was not usable as a narrative, and the group and programme did not make it to the breakthrough phase because of the lack of power resources, despite selected elements being adopted and despite several members of the dominant programmatic group being, in fact, favourable towards essential parts of managed care and having sympathy for them. A second substantial initiative to reorganize the health system targeted the programme of the so-called “citizen insurance.” Again, a majority of members of the dominant programmatic group supported the concept as to content. Apart from the dominant programmatic group, the programme attracted support among the public and – recently in the course of the interest crisis – generated consent among private health insurances due to the increasing external problem pressure. Yet, the main proponent of the programme of citizen insurance was and still is in deep personal conflict with the leading figures of the dominant programmatic group. At the top of the group of advocates behind a citizen insurance are strongly polarizing partisan politicians who so far did not manage to form a programmatic group holding resources and being powerful. Furthermore, the Greens and the Social Democrats alternately employed the concept in several electoral campaigns, which makes it almost impossible to form a party-spanning group of supporters. Programmatic groups do not function in their logic if they only involve members of specific parties and if their programme is in fact a partisan programme. As a consequence, and in spite of relatively broad support, the programme did not reach the phase of breakthrough because it is too attached to prominent partisan actors (actor inclusiveness).

Phase IV: Reactionary policy-making in economic prosperity

Since the last major policy reform of 2011, the policy programme and the programmatic group have been declining. Reasons for this decline are numerous, but the most important ones are that leading representatives of the group have reached retirement age, that the group increasingly experienced internal conflict because of tangible decisions, and that there is a partial disillusionment regarding the substantial results of the reform programme. In light of the current decline of the programme, new programmatic groups have the chance to occupy central positions. If key positions are replaced with actors that are part of a social group that emerged out of the usual bodies of cooperation, such actors may emerge as a new programmatic group. A recent example of strong and close cooperation on a central topic in German health care is that of care policy. Within a concerted action on care policy, a group of actors from state, unions, associations and self-governance repeatedly met to work out reform proposals that are now considered for future reforms in this policy area. The lead actor in writing the reform programme has been promoted within the ministry and now occupies a central post in the policy formulation process (source for this information is an interview in the ministry). A smaller programmatic group has already taken its chance to realize its programme of strengthening and valorising nursing professions in several smaller reform steps. The recent Covid-19 pandemic puts the issue of care policy on the agenda but sheds light on a formerly neglected group of actors committing themselves to a programme on public health in connection with scientific advice, as it has been the case in the UK (Ettelt and Hawkins Reference Ettelt and Hawkins2018). Here, we see much leeway for the establishment of (a) further, encompassing programmatic group(s). Other initiatives coexist, for instance, with respect to the digitalization of the German health system or patient-oriented goal governance – but none of these groups and programmes have reached the breakthrough phase so far, nor is it clear that they have already formed as a programmatic group (see Figure 2).

Conclusion

This contribution presents insights into policy processes and avenues for future research in several respects. Firstly, the PAF constitutes an additional theoretical lens to capture policy process dynamics, especially how the dominance of groups and their programmes persists and how it eventually ends. Informed by the empirical case and existing literature, its main argument is that the institutionalization of policy programmes and their programmatic actors, as well as the inclusiveness and pluralism of programmatic groups, affects policy programme persistence. With a view on programmatic groups and policy programmes as irrevocably tied, the PAF also explains strategies that are not covered by all established theories of the policy process but nonetheless quite ancient knowledge: The reformers of today become the conservatives of tomorrow.

Secondly, while there is evidence that PAF’s theoretical claims sometimes hold true in explaining policy processes, one must acknowledge that this is not always the case. There are important limitations and scope conditions that constrain the formation of programmatic groups and policy programs’ success. First of all, while all political systems entail opportunities for networking and thereby present the basis for contact and joint development of ideas between policy actors who later may cooperate based on their biography, these chances are not equally distributed across political systems. Given that the programmatic approach roots in French political science, the École Nationale d’Administration (ENA), which every individual who becomes a powerful policy actor has typically run through, presents the place to be when programmatic actors are born. In the analysed case, the programmatic group and its policy programme were initiated in the Enquete Commission, but this is a non-regular body of cooperation. Policy programmes and programmatic actors, therefore, need commissions where they can begin cooperation, think, and develop ideas to mould the sectoral policy of a state over a longer period of time.

Thirdly, and relatedly, there are and will be situations in which no programmatic group or policy programme exists. This is currently the case in German health policy, after the period of programmatic dominance, because reforms largely respond to upcoming problems with a generous expense policy instead of tackling structural problems. Here, PAF does not provide the theoretical means to explain these developments while other theories do. Therefore, it is important to note that PAF can provide an added value in some cases but not in others. Similarly, the idea of policy programmes following cyclical patterns is sometimes visible and sometimes not. Yet, there are instances in which the link between programmatic groups and policy programmes is connected to the rise and decline of political careers, and this is when PAF unfolds its explanatory potential.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding sources

This work was funded by the DFG grant number DFG BA 1912/3-1 and the ANR grant number ANR-17-FRAL-0008-01.

Data availability statement

This study does not employ statistical methods and no replication materials are available.