In addition to campaign contributions, individuals are responsible for nearly three-quarters of donations to a large and growing nonprofit sector in the United States (US) (Schervish et al. Reference Schervish, O’Herlihy and Havens2002) – much of which has important political consequences. Individual donations in America grew from $28.5 billion in 1975 to $143.6 billion in 1995, then to $190.16 billion in 2009 and more recently to $217.79 billion in 2011 (Yen Reference Yen2002; National Center for Charitable Statistics 2013). Indeed, this growth in charitable giving has outpaced economic growth for the past half century (Brooks Reference Brooks2006). As we discuss in this study, the amount of nonprofit funds that are used for political expenditures makes the nonprofit sector highly consequential for the American political landscape (Levine Reference Levine2015).

As a result of the growing connection between nonprofit organisations and politics, understanding what motivates Americans to donate their money is becoming increasingly relevant for both political science and public policy scholars. In this study, we introduce a novel experimental design in which participants are given a choice to donate money they have received to a selection of competing nonprofit organisations or, alternatively, to simply keep it for themselves. Specifically, we examine how negative emotional appeals to either one or to both of these competing organisations influence donation behaviour.Footnote 1 We find that negative emotional appeals do not affect the total amount of money donated to organisations, but rather increase the proportion of funds donated to one organisation as opposed to another. Furthermore, we find that negative emotions mobilise donations in isolation, but multiple negative emotional appeals cancel each other out in competitive settings – settings that, we argue, are more illustrative of real-world scenarios.

Existing scholarly research yields important insights about the types of appeals that are most likely to elicit donations. For example, experimental studies of philanthropic donations demonstrate that visual imagery can increase contributions (e.g. Perrine and Heather Reference Perrine and Heather2000) and that individuals are most likely to donate to recipients that align with their own identity group (Chen and Li Reference Chen and Li2009). Emotional messages appear particularly effective in motivating individuals to defend one’s own group-based interests (e.g. Klar Reference Klar2013). Specifically, negative emotions (i.e. anger and guilt) induce discontent among recipients who are subsequently “assuaged through the opportunity to donate to the identified cause” (Merchant et al. Reference Merchant, Ford and Sargeant2010). As a result, negative emotional appeals most effectively increase the amount of funds contributed (Haynes et al. Reference Haynes, Thornton and Jones2000; Patil et al. Reference Patil, Singh and Mishra2008).

Yet, existing studies focus on individual giving in isolated settings. In reality, individuals’ financial resources are limited (Brady et al. Reference Brady, Verba and Schlozman1995), and with nearly 1.5 million nonprofit organisations in the US alone, potential donors are confronted with multiple competing organisations seeking contributions. Existing research, thus, cannot distinguish between two possibilities that might occur in competitive settings: (1) negative emotional appeals lead individuals to donate a larger overall sum of money to solicitous organisations; or (2) negative emotional appeals do not affect the total amount of money donated, but rather increase the proportion of funds donated to one organisation as opposed to another. By administering our study in the context of a competitive setting, we are able to identify that indeed the latter alternative takes place – that is, multiple competing appeals do not increase overall donations. We find that even a highly effective appeal has less of an effect on the extent to which an individual donates money than on to whom he/she donates money.

In addition, we are also able to contribute to broad questions of who gives with a unique variable measuring actual revealed preference. Instead of relying on notoriously inaccurate self-reports of philanthropic giving, we measure respondents’ decisions to actually give money in a controlled setting with low social desirability pressures. Overall, these findings have important implications for how individuals negotiate between multiple appeals for donations and for how political and nonprofit organisations can compete in their quest for financial support.

How changed regulations increased the relevance of donations to public policy

There exist nearly 1.5 million nonprofit organisations in the US classified by the American Internal Revenue Service (IRS) as 501(c) organisations. Their relevance for politics and public policy has undergone a recent explosion, thanks to a particular class of organisations known as 501(c)(4) groups: civic organisations deemed to operate exclusively for the promotion of social welfare. Although 501(c)(4) organisations were created nearly a century ago when Congress enacted the Revenue Act of 1913, their activity was spurred by a 1981 IRS Revenue Ruling that such organisations may legally engage in political campaign activities that support or oppose political candidates “so long as such activities do not constitute the organization’s ‘primary’ activity” and are not coordinated with particular candidates nor campaigns. Following Federal Election Commission restrictions on individual and corporate donations, nonprofit organisations suddenly became “the covert means of political financing due to their ability to collect unlimited contributions without disclosure” (Kalanick Reference Kalanick2011, 2263). Indeed, the 2010 midterm elections came to be known as “the 501(c)(4) election” (Kalanick Reference Kalanick2011, 2263), with over one hundred 501(c)(4) organisations spending $95 million on political expenditures.Footnote 2

This massive increase in 501(c)(4) organisations is relevant to political science and public policy scholars for two primary reasons. First, individual donations channelled through 501(c)(4) organisations are directly connected to political campaigns and policy output. Second, this growth in nonprofit organisations has created substantially more competition for donors’ limited dollars. The expansion of the nonprofit sector and the demands it places on individuals to donate show no signs of abatement, and the antecedents to donations are an area ripe for examination.

The role of individual giving in an increasingly competitive nonprofit sector

Most occasions of giving, according to recent research, follow targeted solicitations. The recent growth in the number of nonprofit organisations has, thus, resulted in Americans facing an ever-growing number of appeals for financial donations (see Yavas et al. Reference Yavas, Riecken and Parameswaran1980; Van Diepen et al. Reference Van Diepen, Donkers and Franses2009). Bryant et al. (Reference Bryant, Jeon-Slaughter, Kang and Tax2003) use the 1996 Independent Sector Survey on Giving and Volunteering to find that 85% of donations follow solicitations, and, more recently, Bekkers (Reference Bekkers2005) relies on survey data to show that 86% of donations over a two-week period come on the heels of a solicitation for funds. Experimental designs similarly demonstrate that active solicitations are indeed most effective at instigating charitable giving as compared with providing opportunities for passive donations (Lindskold et al. Reference Lindskold, Forte, Haake and Schmidt1977).

How do individuals navigate among these competitors? Levine’s (Reference Levine2015) study of political donation behaviour argues that the decision to spend money on one target is weighed against competing targets. That is, the finite nature of individual finances dictates that spending does not draw on a bottomless well but rather involves zero-sum decisionmaking to either spend money on Target A or a competing Target B. As an example, Brown et al.’s (Reference Brown, Harris and Taylor2009) observational analysis suggests that the increase in donations to relief efforts following the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean resulted in decreases in donations to other charitable causes. This phenomenon is known to researchers of the nonprofit sector as “donor fatigue” (Wiepking Reference Wiepking2008; Van Diepen et al. Reference Van Diepen, Donkers and Franses2009), which stems from a bombardment of appeals for financial support. How individuals determine their donation behaviour in this highly competitive nonprofit environment is the question to which we now turn.

Negative emotions and effective solicitations in isolated versus competitive settings

Effective solicitations in isolation

Not all solicitations are equally effective, as a vibrant tradition of research indicates. For example, individuals are more altruistic towards philanthropic organisations that align with their ingroup (group with which individuals identify) as opposed to those that align with their outgroups (groups with which individuals do not identify) (Chen and Li Reference Chen and Li2009). Similarly, Bekkers and Wiepking (Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011, 9), in their review of empirical work on philanthropic giving, state that the “first prerequisite for philanthropy” is “awareness of needs”, which can stem from donors’ personal experiences (Bendapudi et al. Reference Bendapudi, Singh and Bendapudi1996). For example, we know that a survivor of a particular disease is more likely to donate to a charity targeting that disease (Bekkers Reference Bekkers2008) or a victim of a particular cause (Polonsky et al. Reference Polonsky, Shelley and Voola2002). Indeed, “philanthropy is a means to reach a desired state of affairs that is closer to one’s view of the ‘ideal’ world” (Bekkers and Wiepking Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011, 27); therefore, sharing common beliefs or values with a particular organisation is an important mechanism that motivates donors to give (e.g. Keyt et al. Reference Keyt, Yavas and Riecken2002; Francia et al. Reference Francia, Green, Herrnson, Powell and Wilcox2005).

Invoking negative emotions such as anger can further elevate the effectiveness of these appeals. This should not be surprising; empirical evidence from both the social sciences (e.g. Marcus et al. Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000) and the physiological sciences (e.g. Damasio Reference Damasio2003) demonstrates that “there can be no reason (or at least effective decision making) without emotion” (Redlawsk et al. Reference Redlawsk, Civettini and Lau2007). Anger stimulates novel behaviours (Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011) and is a key pathway to collective action (e.g. van Zomeren et al. Reference Van Zomeren, Spears and Fischer2004), and thus it is perhaps no surprise that, among all political ads featured in the 1999 and 2000 elections, Brader (Reference Brader2006) found that the most common negative emotion invoked was anger (46%). Experimental work on charitable organisations has similarly found that incorporating negative emotions into solicitations is an effective fundraising technique, as donors then proactively seek out positive emotions by donating to the cause at hand (Merchant et al. Reference Merchant, Ford and Sargeant2010). Collectively, these studies suggest that an organisation seeking contributions would be well served to evoke negative emotions in order to galvanise support.

Effective solicitations in competitive settings

We are concerned, however, that the settings in which these studies were situated did not feature competition between sources soliciting donations. There is near-consensus across nonprofit scholars from varying fields that Americans are “oversolicited”. Estimates vary, but recent statistics indicate that, for example, in 2006, American families received over 700 million philanthropic solicitations by mail (Patil et al. Reference Patil, Singh and Mishra2008), whereas Diamond and Iyer (Reference Diamond and Iyer2007, 82) estimate that 14 billion charitable solicitations are sent by mail each year.

However, despite the many competing appeals, over 90% of Americans give to fewer than 10 organisations annually (Sinclair Reference Sinclair1999). How individuals navigate among these competing organisations has not often been addressed.

The process by which multiple and competing appeals become mutually ineffective has been empirically documented in the field of social psychology. Studies on competitive framing – that is, the presentation of two opposing arguments regarding a particular policy – show that two opposing but equally persuasive frames typically cancel each other out, resulting in no change in the support for either argument (e.g. Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007). For example, Klar (Reference Klar2013) presented adults who identify both as parents and as Democrats with questions that reminded them of either their parental identity, their Democratic identity or both their parental and Democratic identity. She found that, when only one identity was presented, respondents expressed policy preferences that aligned with that particular group’s interests. When both identities were presented, however, they cancelled each other out and had no effect on policy preferences.

Yet, we are unaware of any existing research that connects these empirical findings with the observed phenomenon of donor fatigue. In studying competing arguments in favour of versus opposed to same-sex marriage, Brewer (Reference Brewer2003) noted that three possible scenarios could arise when an individual is subject to competing appeals: one is that they will become confused and “fail to learn the contents of either” appeal. A second alternative is that the competing message could “induce uncertainty” about the meaning of either appeal. Finally, individuals might become ambivalent about the issue at hand and reject both appeals (pp. 177–178). Regardless of which route occurs, the outcome is the same: both appeals go unheeded. This endpoint – that is, a rejection of both competing messages – is indeed what social psychologists studying preference formation in the face of competition have found (Sniderman and Theriault Reference Sniderman and Theriault2004; Klar Reference Klar2013).

Hypotheses

By bridging work by nonprofit scholars with the aforementioned work in the field of social psychology, we respond to David Horton Smith’s call that “scholars concerned about voluntary action research should consciously seek out cross-disciplinary inputs” (Reference Smith1975). We conceptualise a charitable solicitation as a type of argumentation – a justification for donating to one side over another. In line with what scholars have found with respect to competitive framing (Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Klar Reference Klar2013), we expect that individuals who are subject to two personally relevant solicitations will, on average, donate funds to each of the organisations at equal rates (H1).

We then begin to test the effect of negative emotional appeals in two stages. First, given the earlier findings by Merchant et al. (Reference Merchant, Ford and Sargeant2010), we expect that, when respondents are exposed to competition between one negative emotional appeal and one nonemotional appeal, they will donate significantly more funds towards the organisation aligned with the negative emotional appeal but will not alter the total amount donated by the individual. Furthermore, we examine two negative emotional appeals in a competitive setting. Existing studies on donor fatigue and competitive frames collectively suggest that two negative emotional appeals will effectively cancel each other out, resulting in no substantial financial gains for either of the associated organisations (H3). In order to test these hypotheses, we developed a unique experimental design, which we describe in the following section.

Experimental design

Measuring donation behaviour is particularly challenging because much of what we know regarding policy support and related behaviours come from self-reported survey measures. When it comes to a normatively desirable behaviour such as philanthropic donations, these measures are frequently biased in favour of the normatively preferred action (Burt and Popple Reference Burt and Popple1998). Psychological (Schlenker and Weingold Reference Schlenker and Weigold1989) and sociological (Goffman Reference Goffman1959) theories of self-construction suggest that individuals wish to construct themselves in a manner that will be pleasing to others (Holbrook and Krosnick Reference Holbrook and Krosnick2010). When asked matters of opinion, we are, thus, susceptible to answering in a manner that will be most pleasing – and least controversial – for the sake of, simply, saving face. For example, social desirability pressures have been shown repeatedly to influence self-reports of drug use and sexual behaviour (Tourangeau and Yan Reference Tourangeau and Yan2007), electoral participation (Karp and Brockington Reference Karp and Brockington2005) and even candidate preference (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2009). Therefore, when Gallup reports that 78% of their nationally represented sample claim to have donated money to charity in the previous year, there is certainly reason for suspicion.

To be sure, methods of dealing with social desirability pressures do exist, including dictator game settings in which respondents’ charitable donations towards one another approximate their likelihood to engage in philanthropy (Chen and Li Reference Chen and Li2009), field experiments in which scholars coordinate with organisations during their campaign for donations (e.g. Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick2004; Diamond and Iyer Reference Diamond and Iyer2007) and extensive interviews with individuals to determine their personal likelihood to donate (e.g. Asgary and Penfold Reference Asgary and Penfold2011). Dictator games in a laboratory setting provide the researchers with a large degree of control so as to ensure strong internal validity; however, external validity is weak due to the setting and due to the fact that individuals are not, in fact, donating their own funds. Field experiments (e.g. Van Diepen et al. Reference Van Diepen, Donkers and Franses2009) provide a greater measure of external validity in that respondents donate their own money in a real-life context, but these settings limit the degree to which researchers can exert control over the experimental study. For example, respondents are often able to share their experimental stimuli with one another, thus potentially violating the stable unit treatment value assumption; furthermore, researchers are limited by the prerogatives granted to them from the cooperating organisations. Finally, intensive interviewing allows for the qualitative assessment of the unique characteristics that may enhance donations, but it lacks the ability to identify a causal relationship due to myriad confounding variables.

With these considerations in mind, we chose to administer our study using a controlled experimental method while still enabling our respondents to donate actual money to a variety of real-life organisations. Furthermore, we incorporated real-world organisations that appeal to personally relevant identity groups (Bekkers and Wiepking Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011). We now turn to elaborating on our sample of respondents, the corresponding political and charitable organisations we incorporated and the experimental procedure we pursued.

Organisations in the study

Given our real-world setting, it was essential to incorporate organisations that would appeal to the sample we employed in this study. We thus chose two organisations that appeal to common experiences and shared values (Bekkers and Wiepking Reference Bekkers and Wiepking2011). The first was an organisation focused on child welfare, which we expected would align with the values of parents, whereas the second and third were political organisations, which aligned with the values of partisans (i.e. Democrats and Republicans). We will first describe each of these three organisations and subsequently discuss the sample of Democratic and Republican parents who participated in this study.

Dreams for Kids is a 501(c)(3) organisation based in Chicago, Illinois, which describes itself as “a volunteer based, registered nonprofit 501(c)(3) children’s charity that breaks down social barriers and ends the isolation of at-risk youth”. By focusing its philanthropic efforts on children, Dreams for Kids serves as an ideal organisation to align with the common experiences of parents.

The second organisation used in this study is America Votes, a 501(c)(4) organisation based in Washington, DC, whose self-described mission is to “work with over 300 state and national partner organizations to advance progressive policies”. America Votes works to support Democratic candidates in districts across the country, and thus serves as a well-suited 501(c) organisation to align with the identity-based interests of Democrats. For Republican identifiers, we included the 501(c)(4) organisation Crossroads GPS, which acts as an independent organisation that aligns primarily with conservative or Republican interests.

Participants

We embedded our experimental design into a survey that was distributed to voters leaving the polling place in Illinois’ 9th district and Michigan’s 15th districtFootnote 3 during Election Day of 2012. Voters participating in the election had an unusually high tendency to identify with both groups that are personally relevant to the organisations we employed in this study: parents and partisans. Parents are particularly common among voters, as they are especially likely to turn out to vote relative to adults without children (e.g. Plutzer Reference Plutzer2002, 43). We were, thus, assured that our sample would contain a large proportion of individuals whose interests align with Dreams for Kids. Given that the study was administered during a presidential election, we could be confident that a high number of self-identified partisans would participate as well, and therefore both partisan organisations (Crossroads GPS and America Votes) would similarly appeal to our sample.

Procedure

Seven trained pollsters distributed themselves at voting locations on Election Day, and as voters left the polling place they were offered $5 in cash to complete a self-administered survey that took approximately 5 minutes. Respondents who consented to participate randomly received one of the three versions of our survey.Footnote 4 Version 1 of the survey contained a series of policy questions. Version 2 began with a negative emotional appeal to parents, followed by a nonemotional appeal to partisans and then the same policy questions that appeared in Version 1. Version 3 included both a negative emotional appeal to parents and a negative emotional appeal to partisans, as well as the same policy questions that appear in Versions 1 and 2. At the end of each survey, respondents completed demographic questions that allowed us to identify those respondents who identified as a parent and with a political party.Footnote 5 By isolating our sample to only those who were both parents and partisans, we could ensure that both appeals were personally relevant for our sample. All analyses in this study were, therefore, performed only among those respondents who identified both as parents and partisans, which amounted to 582 of the 682 (85%) total respondents.

Once the respondents completed the survey, they were informed that their cash reward – an envelope with five $1.00 bills – was stapled to the back of the survey (see Appendix 1 for specific wording). Respondents were told that they could take as much of the $5.00 reward as they would like, but they also had the option of donating some or all of the money to a nonprofit organisation listed on the back of the survey. The organisations that were listed included Dreams for Kids, America Votes and Crossroads GPS.

We were particularly sensitive to the potential for social pressure to donate funds. In order to minimise this possibility, we took several precautions. First, pollsters instructed all the participants to make their donation decision in private. They were instructed to detach the envelope from the survey, write down the amount they were donating on their anonymous survey (which contained absolutely no identifying information), insert the corresponding amount into the envelope, reseal the envelope and finally place the envelope (whether or not there was money inside) inside a cardboard box that contained many other such envelopes. In this manner, it was obvious to both the interviewers and the participants that the interviewers had no way of knowing whether, and how much, participants chose to donate. At the end of the study, we calculated the amount of money that was, in the aggregate, to be donated to each organisation and sent the corresponding amount to each one. Thus, although we could not identify which individual respondents chose to donate by preserving anonymity and, therefore, minimising social desirability pressures, we were still able to calculate the average donation across each experimental group.

This experimental design produced three conditions as depicted in Table 1.

Table 1 Overview of the experimental conditions

Note: Percentages do not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Individuals randomly assigned to Condition 1 received no appeals at all. They simply completed the survey and were then given the option to donate money to the charities listed or to keep the money. The condition in which no specific appeals were used served as our baseline against which we compared the donation behaviour of individuals in the following experimental treatment groups.

Individuals randomly assigned to Condition 2 received a brief anger appeal targeting their parental identity (“Some parents are angry that the concerns they have as a parents are being threatened by current policies. When you evaluate policies, how important is to you that your concerns as a parent are represented?”) and a brief nonemotional appeal to their political identity (“When you evaluate policies, how important is to you that your political values are represented?”). Those randomly assigned to Condition 3 received two competing anger appeals: an anger appeal targeting their parental identity (same wording as above) and an anger appeal targeting their political identity (“Some voters are angry that their political values are being threatened by current policies. When you evaluate policies, how important is to you that your political values are represented?”).

Results

Before turning to the results, we first provide a brief summary of the amount of donations that were given across the entire sample of respondents. As we suspected, the incidence of actual donations tends to differ markedly from conventional self-reports of philanthropic behaviour. For example, Gallup has found that 78% of a national sample reported that they had been asked for philanthropic donations and, among them, 80% reported that they had donated money (Bryant et al. Reference Bryant, Jeon-Slaughter, Kang and Tax2003). In our sample, we found that 52% of participants actually donated the money they received in compensation for completing the survey. The Gallup question refers to total giving over the previous year rather than at a particular time as ours does. Nonetheless, we suspect our approach yields a more accurate measure in that it demonstrates a revealed behaviour.

Given our unique behavioural measure of donations, we first present some analyses of the determinants of donation behaviour before discussing the results of the hypothesis tests. We do so through an ordinary least squares regression analysis in which the dependent variable is the total amount of money donated, ranging from $0.00 to $5.00. The independent variables are age, education, race, gender, party and ideology.

In our sample, we find no indication that gender, partisanship or ideology affects donation behaviour (see Table 2). Women are just as likely as men to donate, and we find no significant difference between self-identified liberals and conservatives, nor between Republicans and Democrats.Footnote 6 Age has no positive correlation with donation behaviour when measured as an ordinal scale.

Table 2 Predictors of donation behaviour

Note: Cell entries are regression coefficients. The column heading indicates the model specification. For the ordinary least squares (OLS) model, the dependent variable is the total amount of money donated, ranging from $0.00 to $5.00; for the logistic regression model, the dependent variable indicates that the respondent donated (1) or did not (0).

*p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01 (two-tailed).

The only two demographics that do appear to be associated with donation behaviour are education (p<0.10) and race – white (p<0.01). Those with higher education are more likely to donate; we suspect that this is an effect of income. In existing studies, income and education are both commonly shown to predict donations (e.g. Schervish et al. Reference Schervish, O’Herlihy and Havens2002); we did not measure income due to commonly high levels of missingness with the variable. With respect to race, we found that identifying as white is associated with increased donations relative to identifying as a minority group. However, we note that, although the percentage of minority groups in our sample are, in fact, quite similar to the demographics of the census (see Appendix 2), the absolute number of respondents from racial minority groups was small. We next turn to the main results of our experimental study: how do emotional appeals for donations affect donation behaviour in isolation and, critically, in competitive settings?

Main results

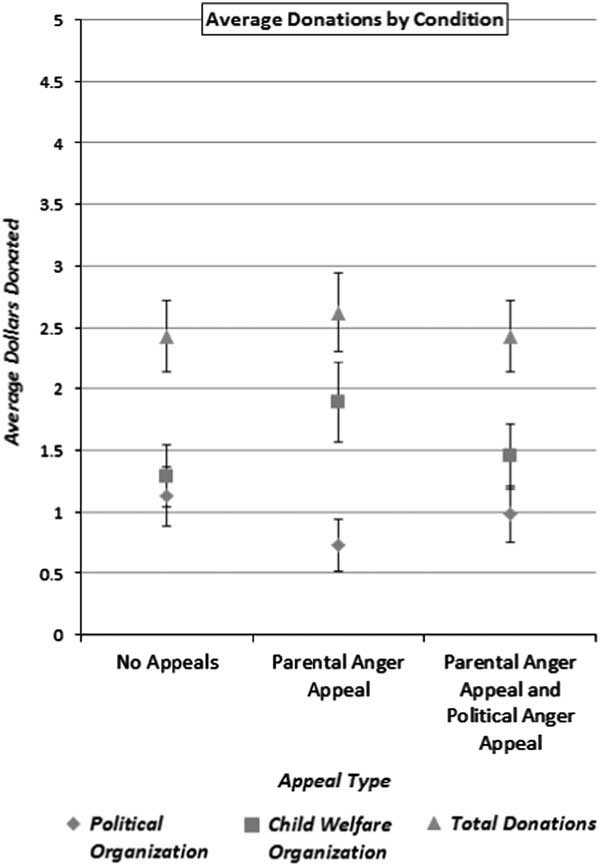

We now assess the effects of the experimental conditions on donation behaviour. We begin by plotting the average amount donated, across experimental conditions, to a political organisation, to a child welfare organisation and in total. In Figure 1, along the x-axis, we display each of our three experimental conditions. From left to right, we see those who saw no appeals, those who saw one parental anger appeal and finally those who saw two competing anger appeals (to both the parental and political identity group). Along the y-axis, we illustrate the average amount of money that was donated within each experimental condition. Finally, the markers within the graph indicate the average amount donated to the political organisation (diamond), the average amount donated to the child welfare organisation (square) and the average amount donated overall (triangle). The black vertical lines to the top and bottom of each marker illustrate the 95% confidence interval.

Figure 1 The effects of competing appeals to negative emotions on donation behaviour.

Our first hypothesis states that respondents who receive no appeals at all will not express any preference for one organisation over the other. On the far left column, we can see that this is the case. The average amount donated to the political organisation is statistically indistinguishable from the amount donated to the child welfare organisation.

Our second hypothesis, in line with previous work, suggests that one appeal evoking anger should effectively increase donations to the targeted organisation. Indeed, as is shown in the middle column along the x-axis, an anger appeal targeting the parental identity results in a significantly large increase in funds donated to the child welfare organisation, and a corresponding decrease in funds donated to a political organisation. In addition, note that the total amount donated does not increase in this condition. Thus, it would be misleading to describe the effect of an anger appeal as “mobilising”: it shifts where the money goes rather than changing the total amount of money donated.

Our most important contribution is to demonstrate that negative emotional appeals in a competitive setting face a different challenge than what they face in isolation. The far right column of Figure 1 illustrates donation behaviour among those respondents who saw both a negative parental appeal and a negative political appeal. As is displayed, we can see that neither the total amount of money donated nor the amount of donations to each of these organisations statistically differ from the scenario in which no appeals are used at all.

Furthermore, we see that total donation amounts stay static at just under $2.50. This indicates that two competitive negative emotional appeals have no effect on increasing total donation behaviour; in fact, they appear to cancel one another out. That is to say, two competing emotional appeals do not persuade donors to give even more than they would have overall. Recall that each participant was provided with $5 to spend on charitable giving. Although the experimental conditions switch the proportion of the funds donated to each of the organisations, the total spending remains notably consistent across conditions. This suggests that individuals may be persuaded in terms of to whom they will donate their funds, but they are resistant to increase the total amount that they donate.

In order to assess the robustness of these results, we conducted an additional series of regression analyses, as shown in Table 3. It is possible that the results are driven by randomisation imbalances of some meaningful set of covariates across experimental conditions. We, therefore, regressed the average amount donated based on the experimental condition – the omitted category being the “control” condition with no appeals at all – controlling for demographics, partisanship and ideology. As can be seen in Table 3, the results remain consistent with our hypotheses and with the results reported in Figure 1: the single anger appeal targeting the parent identity increases donations to the child welfare organisation but does not affect the total amount donated. Meanwhile, the competing appeals do not change either the total amount donated or the share of that amount donated to any single organisation; consistent with our hypotheses and with the earlier results reported in Figure 1, the competing appeals appear to cancel each other out, resulting in no effectiveness relative to the absence of any appeals at all.

Table 3 The effect of experimental condition on donation behaviour

Note: Cell entries are ordinary least squares regression coefficients (standard errors in parentheses). The column heading indicates the dependent variable (ranging from $0.00 to $5.00 in all cases). In the first column, the dependent variable is the total amount donated, summing across organisations; in the second column, the amount donated to a child welfare organisation; in the third column, the amount donated to a political organisation; and in the fourth column, the absolute value of the difference between the amount given to the child welfare organisation and the amount given to the political organisation. The baseline (omitted) experimental condition is the condition with no appeals (see Table 1).

*p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01 (two-tailed).

Another robustness check is as follows. One possibility not explored thus far is that, although the average amount donated is no different across the competing appeals condition and the condition with no appeals at all, this null aggregate finding could mask polarising effects at the individual level. That is, some individuals might be motivated by competing appeals to donate all of their money to one organisation rather than another – but this would not be evident in the examination of the average amount donated if other individuals did the opposite. We, therefore, estimated an additional regression in the final column of Table 3, in which the dependent variable is the absolute value of the difference between the amount donated to a child welfare organisation and the amount donated to a political organisation.Footnote 7 As this regression reveals, there is no change evident at the individual level either; the competing appeals condition again yields identical results to the condition without appeals.

Conclusion and discussion

There exist nearly 1.5 million tax-exempt organisations in America, known as 501(c) organisations. In 2011, public charities reported over $1.59 trillion in total revenues and $2.87 trillion in total assets.Footnote 8 For many of these nonprofit organisations, the goal is to make lasting changes in public policy, and appeals for donations are a crucial element of operations. It is, therefore, no surprise that considerable scholarly attention is spent on the question of how to effectively increase donations at the individual level. This study differs from previous work in two crucial ways: first, we employed a “real-world” behavioural variable in the context of a controlled experimental setting. This allowed us to make a causal statement regarding the effectiveness of the donation appeal while measuring actual donation behaviour. Second, we situated the appeal for money in a competitive setting – one in which individuals faced two simultaneous appeals to closely held identity groups.

Our findings are twofold. First, we examined both a child welfare organisation and a political organisation from each side of the aisle. We studied a large sample of parents who identified with one of the two major political parties, and we employed identity appeals infused with negative emotions (Some parents are angry…). Consistent with previous research, we find that, in an isolated setting, one emotional appeal substantially increases the amount of funds that are donated to the related nonprofit organisation (in this case, the child welfare organisation) but does not increase total donation behaviour.

We then introduced this same appeal tactic in a competitive setting and reached different findings. We found that, although one negative emotion increases donations to a particular organisation, two competing negative appeals appear to cancel each other out and decrease donations back to baseline levels. That is to say, organisations in competition are no better off employing negative emotional appeals than they would be if neither organisation employed such appeals at all.

As with all experimental designs, ours was applied only to a restricted sample: just over 200 participants in the Midwestern US. Furthermore, all participants in our study were voters; it is possible that competing appeals would have different effects among those who are uninterested in politics. Future research might examine the differences between nonvoters and voters when assessing the effectiveness of competing appeals for donations. Nonetheless, the results suggest that the battle over the masses’ pocketbooks is a competition for finite resources. Organisations fighting for precious funds must remain cognizant that appeals that appear effective in isolation may well be muted by the many competitors crowding an increasingly saturated market. Indeed, managers of nonprofit organisations might do well to monitor the messages used by competing organisations as they develop their own fundraising strategies.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Yanna Krupnikov, Adam Seth Levine, David Nickerson, Edella Schlager, Craig Smith, and the editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We also thank Zac Hardwick, Tara Lanigan, Thomas Leeper, Laura Meyer, Kevin Mullinix and Troy Schott for valuable assistance with data collection. An earlier version of this manuscript was presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

Appendix 1: Full wording of donation instructions

To thank you for your participation, you will find $5 in the envelope attached to this survey. This is yours to keep.

If you would prefer to donate any portion of this money to any of the organizations listed below, please write the number of dollars that you would like to donate next to each organization. You may divide your $5 among more than one organization, if you like. Simply leave the number of dollars you wish to donate in the envelope stapled to this survey and the researchers will ensure that the money is properly distributed to the organization(s) of your choice. Your donation is voluntary and anonymous – if you prefer to keep the money or to donate it elsewhere, please take it with you.

America Votes: $___ (enter dollar amount)

America Votes is a nonprofit organization that often supports policies favored by Democrats and Democratic candidates. America Votes “seeks to advance progressive policies, expand access to the ballot, and protect every American’s right to vote”. More information: www.americavotes.org.

Dreams for Kids: $___ (enter dollar amount)

Dreams for Kids is a nonprofit organization dedicated to helping children. Dreams for Kids “empowers at-risk youth and those with disabilities through dynamic leadership programs and life-changing activities that inspires them to fearlessly pursue their dreams and compassionately change the world”. More information: www.dreamsforkids.org.

Crossroads GPS: $___ (enter dollar amount)

Crossroads GPS is a nonprofit organization that often supports policies favored by Republicans and Republican candidates. Crossroads GPS says “most Americans don’t support the big-government agenda being forced upon them by Washington… we work to restore the core principles and values on which this country was founded”. More information: www.crossroadsgps.org.

Table A.1 Demographics of sample compared with US census