Article contents

More Liberal Than We Thought: A Note on Immediate Family Member Immigrants of U.S. Citizens

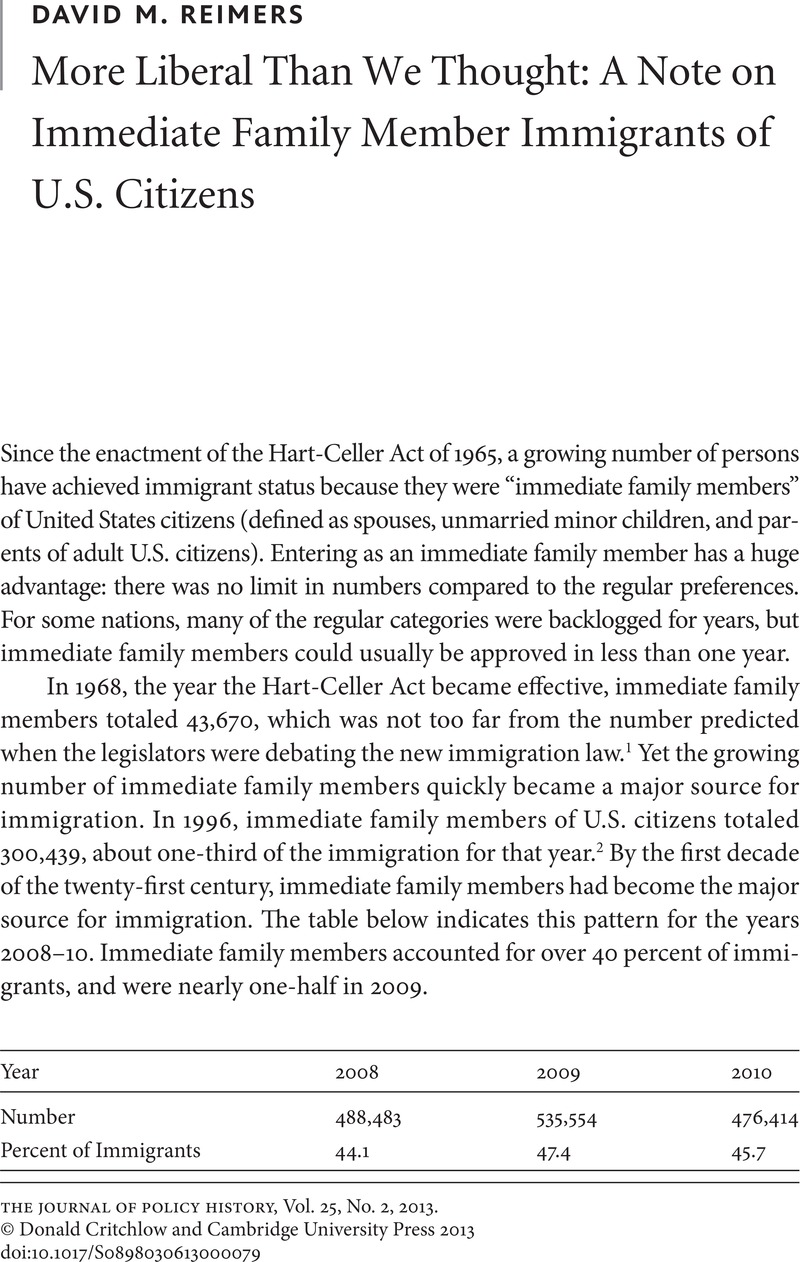

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2013

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Critical Perspectives

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Donald Critchlow and Cambridge University Press 2013

References

NOTES

1. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), Statistical Yearbook of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (Washington, D.C., 1996), 1968, 37.Google Scholar

2. Ibid., 46.

3. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics, U.S. Legal Permanent Residents: 2010 (Washington, D.C., 2008), 2–3.Google Scholar

4. Nonquota family members were not the only group to enter outside the quotas. Ministers and college professors, among others, were exempt.

5. See Zeiger, Susan, Entangling Alliances: Foreign War Brides and American Soldiers in the Twentieth Century (New York, 2010)Google Scholar; and Wolgin, Philip E. and Bloemraad, Irene, “‘Our Gratitude to Our Soldiers’: Military Spouses, Family Re-Unification, and Postwar Immigration Reform,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 40, no. 1 (Summer 2010): 27–60.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

6. U.S. Congress, Senate, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Report no. 1515, The Immigration and Naturalization Systems of the United States, 81st Cong., 2d sess. (Washington, D.C., 1950), 77–78, 465–67, and 590.

7. Ibid., 460, 464–65.

8. Marius Dimmitt, “The Enactment of the McCarran-Walter Act of 1951” (Ph.D. diss., University of Kansas, 1971), 93–94.

9. Divine, Robert, American Immigration Policy, 1924–1952 (New Haven, 1957), 169.Google Scholar

10. For an excellent account of the 1965 law, see Philip E. Wolgin, “Beyond National Origins: The Development of Modern Immigration Policy, 1948–1968” (Ph.D. diss.: University of California, Berkeley, 2011).

11. INS, Annual Reports, 1963, 33.

12. U.S. Congress, House, Hearings Before the Subcommittee No. 1 of the Committee on the Judiciary, Immigration, 88th Cong., 2d sess. (Washington, D.C., 1964), 531–32.

13. Ibid., 12 and 406.

14. U.S. Congress, Senate, Amending the Immigration and Nationality Act, and for Other Purposes, 89th Cong., 1st sess., Report no. 748 (Washington, D.C., 1956), 13.

15. Ibid., 13.

16. See Select Commission on Western Hemisphere Immigration, Final Report (Washington, D.C., 1968).Google Scholar

17. INS, Annual Report, 1969, 40.

18. U.S. Congress, House, “The Immigration and Nationality Act Amendments of 1976,” Committee on the Judiciary, 94th Cong., 2d sess. (Washington, D.C., 1976), 7.

19. DHS, Statistical Yearbook, 2010, 29.

20. Ibid., 28.

21. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon R. Johnson, 1965, vol. 2, entry 546, 1037–40 (Washington, D.C., 6 June 2007).

22. A few other adjustments were expected to add several thousand additional immigrants annually.

23. DHS, Statistical Yearbook, 2010, 30.

24. DHS, U.S. Legal Permanents Residents: 2008, 4.

25. DHS, Statistical Yearbook, 2010, 28. It should be noted that refugee figures include asylees who are already in the United States.

26. U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization, and U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of International Affairs, The Triennial Comprehensive Report on Immigration (Washington, D.C., 1999), 35.

27. Nagi, Mae, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton, 2004), 262.Google Scholar

28. See Reimers, David M., Still the Golden Door: The Third World Comes to America, 2nd ed. (New York, 1992), chap. 4.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

29. DHS, Statistical Yearbook, 2010, 28.

30. For Asian naturalization trends, see Barkan, Elliott R., “Whom Shall We Integrate? A Comparative Analysis of the Immigration and Naturalization Trends of Asians Before and After the 1965 Immigration Act (1951–1978),” Journal of American Ethnic History 3 (Fall 1983): 29–57Google Scholar. See also Schneider, Dorothee, “Naturalization and United States Citizenship in Two Periods of Mass Migration: 1890–1930, 1965–2000,” Journal of American Ethnic History 21 (Fall 2001): 50–82.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

31. U.S. Congress, House, Immigration (1964), 591.

32. DHS, Statistical Yearbook, 2007, 9.

33. DHS, Statistical Yearbook, 2010, 27.

34. Congress did modify the limitation later, and several states picked up part of the aid formerly provided by the federal government. Moreover, many families had children who were U.S. citizens by virtue of their birth in the United States. These citizen children were entitled to assistance by the federal government.

35. For an account of recent nativism, see Schrag, Peter, Not Fit for Our Society: Immigration and Nativism (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2010), chap. 7.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

36. DHS, Naturalizations in the United States: Annual Flow: Report, 2009.

37. For the politics of immigration, see Wroe, Andrew, The Republican Party and Immigration Politics: From Proposition 187 to George W. Bush (New York, 2008).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

38. U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform, Legal Immigration: Setting Priorities (Washington, D.C., 1998), 10.Google Scholar

39. U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, Refugees, Border Security, and International Law, Role of Family-Based Immigration in the U.S. Immigration System, 110th Cong., 1st Sess. (Washington, D.C., 2007). 2.

- 1

- Cited by