The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the outbreak response strategies deployed around the world, including social distancing and remote work directives, have caused major disruptions to daily work routines (e.g., Kniffin et al., Reference Kniffin, Narayanan, Anseel, Antonakis, Ashford, Bakker and Vugt2021; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020). The abrupt transition to remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic is largely a societal and medical necessity rather than a carefully executed and planned strategic choice. Such novel and uncertain contexts have long been recognized to contribute to experienced stress among employees (Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbeke, & Zimmermann, Reference Caligiuri, De Cieri, Minbaeva, Verbeke and Zimmermann2020; Kramer & Kramer, Reference Kramer and Kramer2020). Some scholars have started to theorize on the possible implications of the pandemic on remote work and occupational status (Kramer & Kramer, Reference Kramer and Kramer2020), and the implications for flexible employment more broadly (Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020). Others have presented evidence suggesting that the disruptions experienced in countries that were severely affected by lock-down measures (e.g., China and Italy) have affected individual's psychological well-being (Qiu, Shen, Zhao, Wang, Xie, & Xu, Reference Qiu, Shen, Zhao, Wang, Xie and Xu2020; Rossi, Socci, & Talevi, Reference Rossi, Socci, Talevi, Mensi, Niolu, Pacitti and Di Lorenzo2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Pan, Wan, Tan, Xu, Ho and Ho2020). Organizations face major challenges as the COVID-19 pandemic is impacting work across the globe increasing work demands and requiring continuous adaptation (Kniffin et al., Reference Kniffin, Narayanan, Anseel, Antonakis, Ashford, Bakker and Vugt2021; Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020). Similarly, concerns about worker health and psychological strain are continuously voiced against the backdrop of the pandemic and outbreak responses (Blake, Bermingham, Johnson, & Tabner, Reference Blake, Bermingham, Johnson and Tabner2020; Prasad, Rao, Vaidya, & Muralidhar, Reference Prasad, Rao, Vaidya and Muralidhar2020; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020). Psychological strain refers to ‘aversive and potentially harmful psychological reactions of the individual to stressful work’ (De Croon, Sluiter, Blonk, Broersen, & Frings-Dresen, Reference De Croon, Sluiter, Blonk, Broersen and Frings-Dresen2004, p. 443).

Various theoretical frameworks have been used to study the relationship between job stressors and strain including affective events theory (AET; Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009; Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss, Cropanzano, Staw and Cummings1996) and the transactional stress model (Lazarus & Folkman, Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984). Furthermore, several meta-analyses have been conducted on the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework (Clarke, Reference Clarke2012; LePine, Podsakoff, & LePine, Reference LePine, Podsakoff and LePine2005; Podsakoff, LePine, & LePine, Reference Podsakoff, LePine and LePine2007). Challenge stressors refer to job demands that are rewarding and create opportunity for personal growth and excellence (Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling, & Boudreau, Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000; Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009). Hindrance demands are demands that are viewed as obstacles that obstruct personal growth and hinder one's ability to achieve desired goals (Cavanaugh et al., Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000; Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009). The findings suggest that hindrance and challenge stressors are positively related to strain (LePine, Podsakoff, & LePine, Reference LePine, Podsakoff and LePine2005; Podsakoff, LePine, & LePine, Reference Podsakoff, LePine and LePine2007). However, less is known about what factors may drive this relationship, especially in the context of remote work transitions during the global pandemic. In addition, studies during previous quarantine measures have predominantly focused on workers in healthcare often demonstrating a negative impact on employee wellbeing (Fiksenbaum, Marjanovic, Greenglass, & Coffey, Reference Fiksenbaum, Marjanovic, Greenglass and Coffey2007; Lau, Chi, Cummins, Lee, Chou, & Chung, Reference Lau, Chi, Cummins, Lee, Chou and Chung2008; Shiao, Koh, Lo, Lim, & Guo, Reference Shiao, Koh, Lo, Lim and Guo2007). However, these studies focused primarily on the notion that the potential threat of infection operated as a stressor, ignoring perceptions of hindrance and challenge stressors.

We contribute to recent studies that argued that work during a pandemic could be viewed as a critical incident evoking high-emotional impact that may exceed employees' abilities to cope with ongoing work demands. Typical job stressors, especially during a global health crisis, may include high workload, increased responsibility, unclear job instructions, and job insecurity. However, our knowledge on how and why job stressors are related to psychological strain during the COVID-19 pandemic is still limited (Lai, Shih, Ko, Tang, & Hsueh, Reference Lai, Shih, Ko, Tang and Hsueh2020; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020). To articulate specific mechanisms relevant to the stated aim of the study, we connect the stressor–strain literature with the emerging literature on the impact of COVID-19 in the context of work (e.g., Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020; Kniffin et al., Reference Kniffin, Narayanan, Anseel, Antonakis, Ashford, Bakker and Vugt2021; Kramer & Kramer, Reference Kramer and Kramer2020; Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020) and employee wellbeing (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020). Furthermore, we seek to enrich our understanding about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employee wellbeing by investigating stressor–strain relationships in a country (Finland) that seems to have managed the COVID-19 crisis relatively well.Footnote 1

Thus, taking a broader perspective on the disruptive nature of the COVID-19 crisis on the organization of work, we will contribute to ongoing stressor–strain research by focusing on how various underlying mechanisms (i.e., support, adjustment to remote work, and work–life conflict) and contextual factors (i.e., job control, work structuring, and communication technology use) operate during this time of upheaval. In doing so, we seek to answer the following research question: To what extent do underlying mechanisms related to remote work and support qualify and inform stressor–strain relationships in the context of work during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Theoretical framework

Drawing from AET (Weiss & Cropanzano, Reference Weiss, Cropanzano, Staw and Cummings1996), the transactional stress model (Lazarus & Folkman, Reference Lazarus and Folkman1984), and job demand-control-support (JDCS) model (Karasek & Theorell, Reference Karasek and Theorell1990) research has proposed a stressor framework to explore the relationship between work stressors and wellbeing outcomes (Widmer, Semmer, Kälin, Jacobshagen, & Meier, Reference Widmer, Semmer, Kälin, Jacobshagen and Meier2012; Wood & Michaelides, Reference Wood and Michaelides2016), psychological strain (Crane & Searle, Reference Crane and Searle2016), (counterproductive) work behavior (Clarke, Reference Clarke2012; Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009; Webster, Beehr, & Christiansen, Reference Webster, Beehr and Christiansen2010), thriving at work (Prem, Ohly, Kubicek, & Korunka, Reference Prem, Ohly, Kubicek and Korunka2017), and performance (Zhang, LePine, Buckman, & Wei, Reference Zhang, LePine, Buckman and Wei2014) among other individual and organizational outcomes (see, LePine, Podsakoff, & LePine, Reference LePine, Podsakoff and LePine2005; Podsakoff, LePine, & LePine, Reference Podsakoff, LePine and LePine2007). Hence, we specifically draw on the challenge and hindrance stressor framework to understand how employee wellbeing is affected during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cavanaugh et al., Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000; Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009). Researchers have widely demonstrated the relationships between job stressors and individual- and work-related outcomes, including during the COVID-19 pandemic (van Zoonen & Ter Hoeven, Reference van Zoonen and Ter Hoeven2021). However, we still lack understanding of the ways in which hindrance and challenge stressors are related to wellbeing outcomes. Our purpose in this study, therefore, is to build and test a nomological network of within-individual relationships between challenge and hindrance stressors and wellbeing outcomes, by identifying relevant mediating and moderating mechanisms that qualify these relationships.

Stressor–strain relationships

Work stressors are typically distinguished as challenge stressors and hindrance stressors (Cavanaugh et al., Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000; LePine, Podsakoff, & LePine, Reference LePine, Podsakoff and LePine2005; Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009). Challenge stressors refer to those job demands that can be viewed as rewarding by employees as they provide opportunities for growth and achievement (Cavanaugh et al., Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000). Examples of challenge stressors are job responsibilities, workload, and time pressure. Hindrance stressors, in turn, refer to job demands that impose barriers for employees and prevent personal growth or the achievement of desired goals (Cavanaugh et al., Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000). Examples of hindrance stressors are job insecurity, role ambiguity, and conflict (Webster, Beehr, & Love, Reference Webster, Beehr and Love2011).

Despite the differential impact of challenge and hindrance stressors, and specifically the proclaimed motivational benefits of challenge stressors, previous research has frequently been unable to prove the positive impact of challenge stressors on wellbeing outcomes (Crane & Searle, Reference Crane and Searle2016). The benefits of challenge stressors seem to focus on performance outcomes (Podsakoff, LePine, & LePine, Reference Podsakoff, LePine and LePine2007). However, Crawford, LePine, and Rich (Reference Crawford, LePine and Rich2010) found a positive relationship between challenge stressors and engagement, whereas hindrance stressors were negatively related to engagement. Other studies have demonstrated that both challenge and hindrance stressors contribute to increased psychological strain, including exhaustion, anxiety, and depression (e.g., Boswell, Olson-Buchanan, & LePine, Reference Boswell, Olson-Buchanan and LePine2004). Although the relationship between challenge stressors and psychological strain was not confirmed in recent research (Crane & Searle, Reference Crane and Searle2016), a meta-analysis by LePine, Podsakoff, and LePine (Reference LePine, Podsakoff and LePine2005) demonstrated a positive relationship between both work stressors and psychological strain. Similarly, Lin, Ma, Wang, and Wang (Reference Lin, Ma, Wang and Wang2015), among others, demonstrated that both challenge and hindrance stressors positively relate to psychological strain (despite differing impacts of attitudinal and behavioral outcomes). This is because all stressful job demands are subject to the same psychological process, which requires cognitive and emotional effort, thus, resulting in the forms of strain, anxiety, and fatigue (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ma, Wang and Wang2015). Hence, we hypothesize that both types of work stressors increase employees' psychological strain.

Hypothesis 1: (a) Challenge stressors and (b) hindrance stressors are positively associated with psychological strain.

Stressor–support–strain

Social support is characterized by the helpful relationships employees have with their colleagues and supervisors (Dawson, O'Brien, & Beehr, Reference Dawson, O'Brien and Beehr2016). These relationships may facilitate coping with work stressors which, in turn, enhances wellbeing outcomes (Daniels & Harris, Reference Daniels and Harris2005). Richardson, Yang, Vandenberg, DeJoy, and Wilson (Reference Richardson, Yang, Vandenberg, DeJoy and Wilson2008) have investigated the role of organizational support in stressor–strain relationships. They found that organizational support mediated the relationship between stressors and psychological strain (e.g., depressive symptoms) but not physical strain (e.g., somatic symptoms). The rationale underlying the mediating role of support is based on the notion that employees may perceive job-related stressors as harmful and attribute them to a lack of concern or aid from the organization exacerbating strains (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002; Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Yang, Vandenberg, DeJoy and Wilson2008). Others have theorized a moderating relationship of stressors and support on role-based performance. This was confirmed for challenge demands but not for hindrance demands (Wallace, Edwards, Arnold, Frazier, & Finch, Reference Wallace, Edwards, Arnold, Frazier and Finch2009). The rationale for a moderating effect of support is largely based on the buffering hypothesis, suggesting that a combination of control and support facilitates coping with workplace stressors (Dawson, O'Brien, & Beehr, Reference Dawson, O'Brien and Beehr2016). Support may attenuate the effects of stressors on strains as support may serve an information function, contribute to self-esteem, and increase employees attempts to minimize the effects of stressors (George, Reed, Ballard, Colin, & Fielding, Reference George, Reed, Ballard, Colin and Fielding1993). However, Richardson et al. (Reference Richardson, Yang, Vandenberg, DeJoy and Wilson2008) found strong evidence for the mediation hypothesis, whereas no evidence was found for the moderation hypothesis. The authors concluded that the extent to which support mediates the stressor–strain relationship depends on employees' cognitive appraisal, meaning that stressors first need to be experienced as stressful. Subsequently, employees attribute blame to the organization for not doing enough to help them deal with these stressors.

Consistent with organizational support theory (e.g., Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison, & Sowa, Reference Eisenberger, Huntington, Hutchison and Sowa1986; Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart, & Adis, Reference Kurtessis, Eisenberger, Ford, Buffardi, Stewart and Adis2017) and cognitive appraisal theories (e.g., Folkman and Lazarus, Reference Folkman and Lazarus1984), we argue that the extent to which social support mediates the relationship between job stressors and strain depends on the extent to which employees feel the organization and their colleagues are not doing enough to help them cope with the emerging work demands during these trying times. Social distancing and remote work as part of the outbreak response adopted by most organizations may further contribute to a sense of diminished social support. As such we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2: (a) Challenge stressors and (b) hindrance stressors are negatively associated with perceived social support, which is in turn negatively associated with psychological strain.

Stressor–adjustment–strain

Although many organizations have allowed some form of flexibility in their workplace when it comes to when, where, or how work is conducted, the scale at which employees were mandated to work from home in spring 2020 was unprecedented. In addition, the limited (or lack of) time organizations and employees have had to prepare for this shift does not only raise questions about how employees adapt to these acute changes (Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020), but also how adjustment to these circumstances relates to psychological strain.

Research on remote work and telework has previously examined the factors influencing employee adjustment to remote work (Raghuram, Garud, Wiesenfeld, & Gupta, Reference Raghuram, Garud, Wiesenfeld and Gupta2001). The process of adjustment to new work contexts involves adaptation to the new environmental demands and work stressors. These stressors may stem from the way work is structured, the characteristics of the job (Daniels, Reference Daniels2006), and social relationships (Nelson, Reference Nelson1990). Indicators of successful adjustment include performance effectiveness and satisfaction (Raghuram et al., Reference Raghuram, Garud, Wiesenfeld and Gupta2001; Saks, Reference Saks1995). Furthermore, role clarity was found to be an important factor underlying adjustment to virtual work settings (Raghuram et al., Reference Raghuram, Garud, Wiesenfeld and Gupta2001).

Several studies have investigated the role of job stressors in job adjustment (e.g., Fernet, Guay, & Senécal, Reference Fernet, Guay and Senécal2004; Nelson & Sutton, Reference Nelson and Sutton1991; Sargent & Terry, Reference Sargent and Terry1998). Generally, job stressors such as role ambiguity and conflict are believed to have a negative impact on adjustment, or indicators of adjustment such as satisfaction and productivity (Jimmieson, Terry, & Callan, Reference Jimmieson, Terry and Callan2004; LePine, Zhang, Crawford, & Rich, Reference LePine, Zhang, Crawford and Rich2016; Mazzola & Disselhorst, Reference Mazzola and Disselhorst2019; Raghuram et al., Reference Raghuram, Garud, Wiesenfeld and Gupta2001). Adjustment, in turn, will be negatively related to psychological strain. Research examining employee adaptability suggests that being able to adapt to a change enables workers to manage change-related stress more effectively (Savickas & Porfeli, Reference Savickas and Porfeli2012; van den Heuvel, Demerouti, Bakker, & Schaufeli, Reference van den Heuvel, Demerouti, Bakker and Schaufeli2013). Overall, adjustment to remote work settings – such as virtual work – typically involves adaptation through satisfaction, coping with work demands, and demonstrating effectiveness (Raghuram et al., Reference Raghuram, Garud, Wiesenfeld and Gupta2001). As such, stressors may hinder the process of adjustment, whereas adjustment, in turn, would reduce experienced strain. Hence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3: (a) Challenge stressors and (b) hindrance stressors are negatively related to adjustment to remote work, which in turn is negatively related to psychological strain.

Stressor–work–life conflict–strain

Perhaps, one of the most apparent challenges employees and organizations face with these widespread remote work mandates relates to how workers navigate work and home boundaries. Indeed, research has already suggested that remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates work–life conflict (Giurge & Bohns, Reference Giurge and Bohns2020). As Carnevale and Hatak (Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020, p. 184) note: ‘as the current pandemic continues to unfold, the potential for conflict between the work and family spheres may be greater than ever.’ At the individual level, research has examined the role of boundaries in demarcating specific role domains (Ashforth, Kreiner, & Fugate, Reference Ashforth, Kreiner and Fugate2000; Kossek, Ruderman, Braddy, & Hannum, Reference Kossek, Ruderman, Braddy and Hannum2012; Olson-Buchanan & Boswell, Reference Olson-Buchanan and Boswell2006). These boundaries, whether temporal, spatial, or psychological, help individuals create, maintain, and amend roles to simplify and effectively manage multiple roles. Research is quite univocal about the importance of these individual role boundaries as determinants of work, career, and health outcomes (Cho, Reference Cho2020), including in the context of remote work settings (Raghuram & Wiesenfeld, Reference Raghuram and Wiesenfeld2004).

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the chaotic and uncertain nature of the outbreak may yield negative consequences for employees both in the short term (e.g., increased workload and reduced productivity) and in the long term (e.g., job insecurity and downward career trajectories) (Cho, Reference Cho2020). The former most closely resonates with challenge stressors, the latter with hindrance stressors. It has long been recognized that such stressors may trigger work–family conflict (e.g., Burke, Reference Burke1988; Carlson & Perrewé, Reference Carlson and Perrewé1999). Hence, the implications of the crisis may have a harmful impact on the lives, work, and careers of individuals as demands of work and family may become increasingly difficult to reconcile (Friedman & Westring, Reference Friedman and Westring2020; Petersen, Reference Petersen2020; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020; Sinclair et al., Reference Sinclair, Allen, Barber, Bergman, Britt, Butler and Yuan2020). Rudolph et al., (Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020) suggest that various time-, strain-, and energy-based conflicts, such as spending ‘traditional work hours’ on home schooling children or the increased anxiety and exhaustion caused by the pandemic, may lead to the elevated levels of work–life conflict during the pandemic crisis and afterward.f

The current study suggests that these elevated levels of work–life conflict are, in turn, increasing psychological strain. Previous studies on the relationships between job stressors and work–life conflict have already demonstrated the mediating role of work–life conflict in the relationship between job stressors and psychological burnout (Burke, Reference Burke1988) and emotional exhaustion (Hall, Dollard, Tuckey, Winefield, & Thompson, Reference Hall, Dollard, Tuckey, Winefield and Thompson2010). Others demonstrate strong support for the relationship between work–life conflict and psychological strain (e.g., Boles, Johnston, & Hair, Reference Boles, Johnston and Hair1997; Hogan, Hogan, Hodgins, Kinman, & Bunting, Reference Hogan, Hogan, Hodgins, Kinman and Bunting2015; Kalliath, Hughes, & Newcombe, Reference Kalliath, Hughes and Newcombe2012; O'Driscoll et al., Reference O'Driscoll, Poelmans, Spector, Kalliath, Allen, Cooper and Sanchez2003). Hence, in the context of the current global health pandemic, we hypothesize that work stressors increase work–life conflict, which in turn increases psychological strain.

Hypothesis 4: (a) Challenge stressors and (b) hindrance stressors increase work–life conflict, which in turn is positively associated with psychological strain.

Conditional effects of job control, work structuring, and technology use

Finally, we take a more exploratory approach to investigate the conditions under which these hypothesized relationships can be profound. There are number of studies and essays speculating on the conditions that may qualify the mechanisms underlying employee wellbeing (e.g., Béland, Brodeur, & Wright, Reference Béland, Brodeur and Wright2020; Boswell, Olson-Buchanan, & LePine, Reference Boswell, Olson-Buchanan and LePine2004; Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020; Cho, Reference Cho2020; Kossek, Lautsch, & Eaton, Reference Kossek, Lautsch and Eaton2006; Raghuram, Wiesenfeld, & Garud, Reference Raghuram, Wiesenfeld and Garud2003; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020). Some specifically discuss the role of job control in the context of work during the COVID-19 pandemic (Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020; Cho, Reference Cho2020), others focus on remote work more generally (Kossek, Lautsch, & Eaton, Reference Kossek, Lautsch and Eaton2006). Other factors that may impact the relationships between work stressors and social and individual mechanisms relate to employees' work structuring behaviors (Giurge & Bohns, Reference Giurge and Bohns2020; Raghuram, Wiesenfeld, & Garud, Reference Raghuram, Wiesenfeld and Garud2003) and technology use (Saeed, Bader, Al-Naffouri, & Alouini, Reference Saeed, Bader, Al-Naffouri and Alouini2020; Ter Hoeven & van Zoonen, Reference Ter Hoeven and van Zoonen2020). Thus, we do not claim to be exhaustive nor that these factors are the only relevant contextual factors to consider. We specifically explore the role of job control, work structuring and technology use given their salience both to the current crisis as well as to remote work research more broadly. In addition, we sought to explore both structural aspects related to job (i.e., job control) as well as individual practices (i.e., work structuring and technology use) that may aid in coping with imposed work demands.

Job control

The current circumstances under which employees are mandated to work from home, rather than to select work modes that naturally align with individual and coworker preferences and needs, allow little individual choice (Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020; Cho, Reference Cho2020). In the context of remote work, the main advantage of remote work for employees is the autonomy and control they have over enacting flexible work arrangements (Kossek, Lautsch, & Eaton, Reference Kossek, Lautsch and Eaton2006). More broadly, the JDCS model of occupational stress (Karasek and Theorell, Reference Karasek and Theorell1990) suggests that job control interacts with job stressors to reduce the levels of psychological strain (e.g., Dawson, O'Brien, & Beehr, Reference Dawson, O'Brien and Beehr2016). Specifically, Dawson, O'Brien, and Beehr (Reference Dawson, O'Brien and Beehr2016, p. 399) argue that ‘job demands (i.e., challenge and hindrance demands) and resources (i.e., control and support) uniquely combine to determine resource allocation strategies and subsequent strain responses.’ In addition, Boswell et al. (Reference Boswell, Olson-Buchanan and LePine2004) suggested that when individuals have a great deal of pressure, yet no control, the situation may be particularly undesirable. However, these authors did not find support for a moderating role of job control between stressors and work outcomes, also noting the overall weak support for the role of control in the JDCS model. Again, others note job control may be positive – i.e., stress buffering – for individuals with a high locus of internal control (Meier, Semmer, Elfering, & Jacobshagen, Reference Meier, Semmer, Elfering and Jacobshagen2008). Hence, given these mixed findings, and the relevance of job control for many workers in the current pandemic, we seek to explore the interaction of job stressors and job resources – i.e., job control.

RQ1: To what extent, if any, does job control mitigate the negative impact of work stressors on social support, adjustment to remote work, and work–life conflict?

Work structuring

Structuring a schedule can be important for remote employees working off-site, as they need structure and routines to maintain effectiveness and wellbeing (Canady, Reference Canady2020). Research on virtual work has suggested that individuals who are better able to structure their workday are better able to adjust (Raghuram, Wiesenfeld, & Garud, Reference Raghuram, Wiesenfeld and Garud2003). In addition, these individuals may experience less work–home interference (Raghuram & Wiesenfeld, Reference Raghuram and Wiesenfeld2004), and be able to craft job conditions that mitigate negative impacts of remote work. As such, work structuring is an important factor influencing remote work effectiveness. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, work structuring, or finding a work routine, seems to be the panacea for many remote work challenges, facilitating motivation, performance, and mental health (e.g., Dimson, Foote, Ludolph, & Nikitas, Reference Dimson, Foote, Ludolph and Nikitas2020; Giurge & Bohns, Reference Giurge and Bohns2020; Schmaus, Reference Schmaus2020).

Recent studies examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on work noted that a loss of structure and routine was perceived as problematic. For some, the inability to go to work meant that they felt overwhelmed, whereas for others more significant re-structuring of work patterns, including balancing home working and home schooling, proved to be problematic (Williams, Armitage, Tampe, & Dienes, Reference Williams, Armitage, Tampe and Dienes2020). In addition, for those required to work from home the disruption of established daily (work) routines and schedules may lead to deterioration of positive associations between home and relaxation, leading to health risks (Altena et al., Reference Altena, Baglioni, Espie, Ellis, Gavriloff, Holzinger and Riemann2020). Although not directly measuring work structuring, Abbas and Raja (Reference Abbas and Raja2019) argued that conscientiousness would moderate the relationship between hindrance and challenge stressors and work outcomes. The rationale is that conscientious individuals, similar to those exerting an ability to structure work, would allocate more resources pursuing their targets even under heavy workloads or time pressure. Hence, we would expect individuals that exert a higher ability to structure their work to be better able to adjust, experience less work–life conflict, and would allocate more resources (e.g., find social support) in the wake of challenge and hindrance stressors imposed by work during the pandemic.

RQ2: To what extent, if any, does work structuring mitigate the negative impact of work stressors on social support, adjustment to remote work, and work–life conflict?

Communication technology use

During the pandemic, communication technologies such as Zoom, Microsoft Teams, Skype, and other forms of computer-mediated communication have become necessities in a matter of days. Employees substituted their workstations for their home offices, bedrooms, or kitchen tables (Neeley, Reference Neeley2020). The swift transition to these remote practices was facilitated by the multivalent involvement of communication technologies. Although these technologies have often been found to have both negative and positive implications for remote workers (e.g., Fonner & Roloff, Reference Fonner and Roloff2012; Ter Hoeven, van Zoonen, & Fonner, Reference Ter Hoeven, van Zoonen and Fonner2016), for many employees these technologies and the connectivity they afford are the only way to complete work during these times. Indeed, organizations that have most of their employees working remotely experience increased demands on equipment and connectivity (Koonin, Reference Koonin2020).

Based on earlier research on the role of technologies in virtual work, we assess the extent to which communication technology use may mitigate the negative impact of challenge and hindrance stressors. For instance, Ter Hoeven and van Zoonen (Reference Ter Hoeven and van Zoonen2020) found that technology use mitigates the negative impact of geographical dispersion of workers on pro-social behaviors such as helping others. In addition, research demonstrated that the use of communication technologies may be crucial for teleworkers to prevent feelings of (professional) isolation and deprivation of organizational support systems (Collins, Hislop, & Cartwright, Reference Collins, Hislop and Cartwright2016; Golden, Veiga, & Dino, Reference Golden, Veiga and Dino2008). However, research also provides ample evidence of increased stress and overload as a result of connectivity through organizational information and communication technologies (e.g., Boswell & Olson-Buchanan, Reference Boswell and Olson-Buchanan2007; Fenner & Renn, Reference Fenner and Renn2010; Fonner & Roloff, Reference Fonner and Roloff2012). Hence, research suggests that the use of communication technologies may both amplify experienced work stressors and reduce them, by allowing more effective work practices. The current study examines the extent to which the use of communication technologies exacerbates or mitigates the implications of work stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic.

RQ3: To what extent, if any, does communication technology use mitigate the negative impact of work stressors on social support, adjustment to remote work, and work–life conflict?

Method

Sample and procedure

Data were collected using a convenience sampling method in Finland between May 8th and May 22nd, 2020, which was around 2 months after Finland declared the state of emergency due to the COVID-19 outbreak on March 16th, 2020. The survey was conducted during lockdown measures including remote work mandates. Open survey invitations were published online, and we solicited the help of several large labor unions and ministries to distribute the survey link to their members and employees. The survey was administered using XM software Qualtrics and was programed with forced response options. This way respondents could not submit incomplete surveys. Hence, there were no missing values. Furthermore, respondents who failed the attention checks or dropped out were automatically excluded. This sampling procedure resulted in a total response of 2,242 Finnish employees.

Table 1 provides sample demographic characteristic statistics. In short, respondents were predominantly female (74.4%; n = 1,667), 24.4% identified as male (n = 546) and 1.3% preferred not to disclose their gender (n = 29). They were on average 45.6 (SD = 10.5) years old. The average workweek lasted 38.17 h (SD = 6.59) and respondents reported an average organizational tenure of 10.80 years (sd = 9.96). About 13% of the respondents held a managerial position; hence, 87% indicated they did not have any managerial responsibilities. The data further indicate a substantial change in remote work practices, although many employees reported having some remote work experience (see Table 1).

Table 1. Sample demographic characteristic descriptive statistics

Measures

Questions in the survey were phrased such that the pandemic was emphasized as the context within which statements were to be interpreted. For instance, we added: ‘Please indicate the extent to which you disagree or agree with the following statements. Again, we are interested in your experiences during the COVID-19 crisis’ to the questionnaire. Specifically, related to work stressors and psychological strain we noted that: ‘The following statements are about how much stress you have experienced from the following work-related aspects. We are specifically interested in your work experiences in the period since the COVID-19 measures have been in effect in Finland.’

Work stressors

Challenge stressors were measured using six items adopted from Cavanaugh et al. (Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000) and Rodell and Judge (Reference Rodell and Judge2009). Challenge stressors measure work-related demands or circumstances that are potentially stressful including time pressure and amount of responsibility. For example, ‘The amount of responsibility I have.’ Respondents were asked to indicate how stressful they felt the work-related items were using a 7-point scale ranging from (1) not at all stressful to (7) very stressful. They were explicitly instructed to consider their work experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, including their job responsibilities and experienced time pressure.

Hindrance stressors were measured using five items adopted as well from Cavanaugh et al. (Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000) and Rodell and Judge (Reference Rodell and Judge2009). Hindrance stressors include, for example, perceived levels of red tape and role ambiguity. These demands are viewed as hindrance demands as they present obstacles to gains and growth (Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009). Again, respondents were asked to indicate how stressful they experienced the work-related items such as: ‘the amount of red tape I need to go through to get my job done.’ Following Cavanaugh et al. (Reference Cavanaugh, Boswell, Roehling and Boudreau2000) we asked how much stress each item caused respondents using a Likert scale ranging from (1) produces no stress to (7) produces a great deal of stress.

Mediators and moderators

Social support was measured with four items of the support measure from the work design questionnaire (Morgeson and Humphrey, Reference Morgeson and Humphrey2006). Social support reflects the degree to which a job provides opportunities for advice and assistance from others. Example items include ‘I have the chance in my job to get to know other people.’ Responses were anchored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree.

Adjustment to remote work was measured with a five-item scale adopted from Raghuram et al. (Reference Raghuram, Garud, Wiesenfeld and Gupta2001). The measure assesses an overall state of adaptation related to the inherent tradeoffs involved in adjustment. The measure was previously used to tap virtual workers' adaptation to environmental demands of work. The measure includes items related to the overall satisfaction with remote work, performance as a consequence of remote work, productivity, and commitment. These factors have been found to be critical for adjusting to new work environments. Respondents were asked to indicate their disagreement or agreement on a 7-point scale, ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree. Scale items include: ‘All in all, I am satisfied with remote work.’

Work–life conflict was measured using five items from Netemeyer, Boles, and McMurrian (Reference Netemeyer, Boles and McMurrian1996). The items were adapted to reflect a broader social setting rather than the focus on work–family conflict in the original scale. Sample items include ‘the demands of my work interfere with my social life.’ Response options were anchored from (1) strongly disagree to (7) strongly agree.

Job control was measured using three items of the job diagnostic survey (Hackman & Oldham, Reference Hackman, Oldham, Staw and Sutton1980). The measure examines the level of job autonomy and the items include ‘the job gives me considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do the work.’ Response options ranged from (1) very little to (5) very much.

Work structuring was measured using three items adopted from Raghuram, Wiesenfeld, and Garud (Reference Raghuram, Wiesenfeld and Garud2003). Work structuring refers to employees' attempts to proactively plan and organize their workday. An example item includes: ‘I begin my day setting performance goals.’ Scale anchors were (1) strongly disagree and (7) strongly agree.

Communication technology use measures the degree of mediated communication with colleagues. The measure was based on Kacmar, Witt, Zivnuska, and Gully (Reference Kacmar, Witt, Zivnuska and Gully2003) and Hoch and Kozlowski (Reference Hoch and Kozlowski2014), and included items of email, phone calls, online conferencing, text or instant messaging, social media, and collaboration tools. Since we were interested in the frequency of electronic communication, a sum of all communication technologies was computed. Scores could range from (1) no mediated communication with colleagues to (6) daily communication with colleagues through mediated technologies. The average score was 3.26 (sd = .77).

Outcome

Psychological strain was measured using six items from the general health questionnaire (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1972), also used in the context of remote work and organizational change by Bordia, Hobman, Jones, Gallois, & Callan (Reference Bordia, Hobman, Jones, Gallois and Callan2003). Respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they recently experienced strain symptoms by comparing their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic to the situation before the pandemic. Items include ‘to what extent have you felt capable of making decisions about things?’ Responses ranged from (1) much less than usual to (5) much more than usual.

Results

Measurement model

The hypothesized model was examined with covariance structural modeling using AMOS 23. The validity and reliability of our measures was examined through confirmatory factor analysis. The measurement model demonstrates good model fit: χ2(471) = 3,068.54; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; SRMR = .05, PClose = .647, and RMSEA = .050 (95% CI .048, .051). Convergent and discriminant validity was examined through validity statistics (see Table 2). The average variance extracted (AVE) ranges between .51 and .74, with the exception of hindrance stressors (.35). The range for standardized factor loadings for each construct is reported in Table 2. Discriminant validity was examined through the maximum shared variance (MSV), which ranged between .04 and .47. Additionally, the square root of the AVE was greater than the inter-construct correlations. Overall, these results indicated satisfactory convergent and discriminant validity (See Table 2). Furthermore, composite reliabilities (CR: ranging between .72 and .93) and the maximum reliability (MaxR[H]: ranging between .74 and .94), indicated good measurement reliability. Finally, common method variance was assessed in two ways. First, the Harman's single factor test indicated that one factor explained a total variance of 22.16%. Subsequently, a common latent factor was added to the CFA to examine the shared variance among observed variables. The results indicated that the squared unstandardized factor loading of the common latent factor was -.023. The squared unstandardized coefficient suggested that less than 1% of the variance is due to common method. Hence, these results indicated that the common method variance was not a problem in our data

Table 2. Model validity statistics

CR, composite reliability; AVE, average variance extracted; MSV, maximum shared variance; MaxR(H), maximum reliability.

Square root of the AVE is reported on the diagonal. Correlations above .04 are significant at p < .05.

a No validity statistics are provided for sum score and manifest responses.

b Recoded into dichotomy for gender; 0 = male, 1 = female (29 who did not disclose their gender were treated as missing); manager; 0 = no managerial position, 1 = managerial position.

Contextual variables and controls

Workplace stressors, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, may disparately impact (and be impacted by) employees with specific demographics (Kniffin et al., Reference Kniffin, Narayanan, Anseel, Antonakis, Ashford, Bakker and Vugt2021) or occupational status (Kramer & Kramer, Reference Kramer and Kramer2020; Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020) . Hence, we have included several control variables that may have an impact on the hypothesized relationships in the context of the pandemic. Specifically, this study controlled for several demographics – i.e., gender and age, family status – i.e., household size, children in the household – and included controls related to work status and experience– i.e., managerial position, work hours, and organizational tenure, remote work experience and current frequency of remote work.

Some significant relationships were found between these control variables and the constructs in our model. For instance, the findings indicated that household size was positively related to work–life conflict (B = .053 p = .011). Similarly, employees that reported having children living at home seemed to experience greater conflict (B = .088 p < .001) and more difficulty in adjusting to remote work (B = −.087 p < .009). In terms of work status, employees in managerial positions were particularly troubled by the pandemic as evidenced by significant negative relationships with adjustment (B = −.169 p < .001). In addition, although we also found a positive significant relationship between managerial position and perceived support (B = .09 p = .022), the positive relationship with work–life conflict (B = .467 p < .001) seems to indicate that workers in managerial positions were struggling to juggle with the work and family demands. Employees who reported high frequencies of remote work before the pandemic seem to adjust better to remote work during the pandemic (B = .358 p < .001). In addition, employees that reported higher remote work frequency during the pandemic also seem to report higher ratings on adjustment (B = .206 p < .001). These findings suggest that remote work experience and frequency positively impacted employees' adaptation to these work settings. It should also be noted, however, that these findings did not impact the hypothesized relationships in the model. Hence, the findings demonstrated that all model parameters in the final model held true when controlling for these variables. Further examination of potential interactions did not yield significant results; and thus, these variables were excluded from the final model for reasons of parsimony.

Structural model

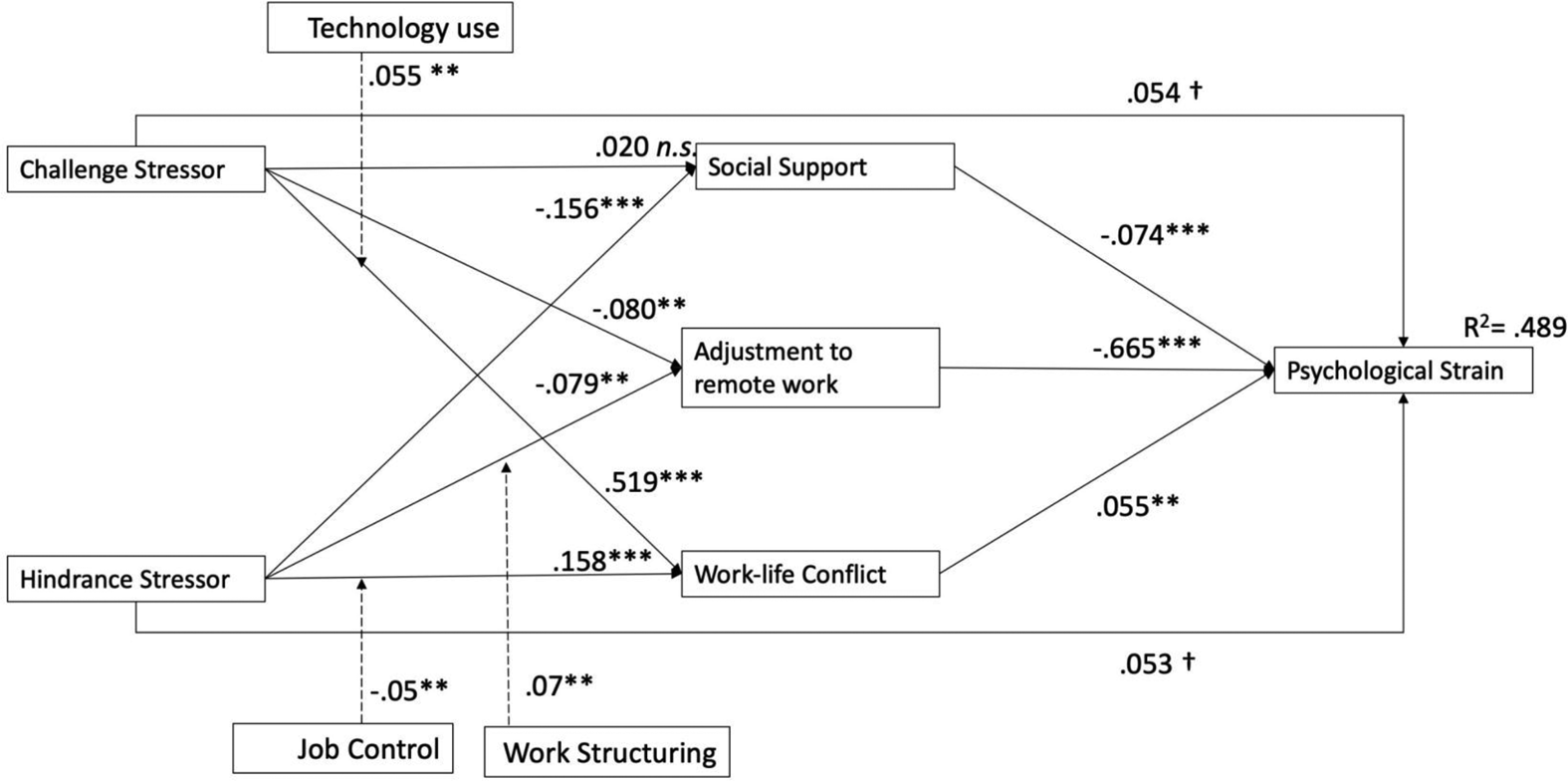

The structural model also indicated good model fit χ2 (474) = 3,105.75; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; SRMR = .05, PClose = .584, and RMSEA = .050 (95% CI .048, .051). Below, we report the results of our hypotheses testing based on unstandardized regression coefficients and confidence intervals. Standardized solutions are provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Simplified regression model with standardized results.

Note: Significance is flagged: ***p < .001; **p < .05; †p < .10

Direct effects

Hypotheses 1a and 1b reflect the expectation that challenge and hindrance stressors are directly and positively related to psychological strain. The results indicated that challenge (B = .046, 95% CI [−.003; .090], p = .063) and hindrance stressors (B = .051, 95% CI [−.006; .104], p = .072) demonstrated a positive relationship with psychological strain. However, these relationships just fail to reach significance, lacking support for hypotheses 1a and 1b.

Indirect effects

Hypothesis 2 posits that work stressors may reduce perceptions of social support, which, in turn, may lead to increased psychological strain. The findings indicated that challenge stressors (B = .027, 95% CI [−.054; .103], p = .518) were not significantly related to support. Hindrance stressors, on the contrary, were negatively associated with perceptions of support (B = −.232, 95% CI [−.352; −.122], p = .001). In addition, perceived social support was negatively related to psychological strain (B = −.048, 95% CI [−.078; −.020], p = .001), suggesting that those experiencing more support experience less psychological strain. Given these results, the implied indirect relationship between challenge stressors and strain through social support was not significant (B = −.001, 95% CI [−.006; .002], p = .407). The indirect relationship between hindrance stressors and strain through social support was significant in the hypothesized direction (B = .011, 95% CI [−.078; −.020], p = .001). Hence, hypothesis 2a was not supported whereas hypothesis 2b was supported.

Hypothesis 3 reflected the assumption that work stressors present barriers for employees that make it more difficult to adjust to remote work settings, which in turn is negatively related to psychological strain. The findings demonstrated that challenge stressors (B = −.148, 95% CI [−.306; −.017], p = .030) and hindrance stressors (B = −.148, 95% CI [−.254; −.036], p = .011) were both negatively associated with adjustment to remote work. Adjustment to work was negatively associated with psychological strain (B = −.307, 95% CI [−.336; −.280], p = .001). These results yielded significant indirect relationships between challenge stressors and psychological strain through adjustment (B = .045, 95% CI [.010; .078], p = .011) and between hindrance stressors and psychological strain through adjustment (B = .051, 95% CI [.005; .095], p = .031). These results supported hypotheses 3a and 3b.

Hypotheses 4a and 4b focused on the role of work–life conflict in the relationship between role stressors and psychological strain. Challenge stressors (B = .915, 95% CI [.821; 1.007], p = .001) and hindrance stressors (B = .317, 95% CI [.198; .432], p = .001) were both positively and significantly related to work–life conflict. Work–life conflict was also positively related to psychological strain (B = .027, 95% CI [.003; .052], p = .033). These results yielded significant positive indirect effects of challenges stressors on strain through work–life conflict (B = .024, 95% CI [.003; .049], p = .030), and of hindrance stressors on strain through work–life conflict (B = .008, 95% CI [.001; .019], p = .025). Hence, hypotheses 4a and 4b were both supported.

Moderations

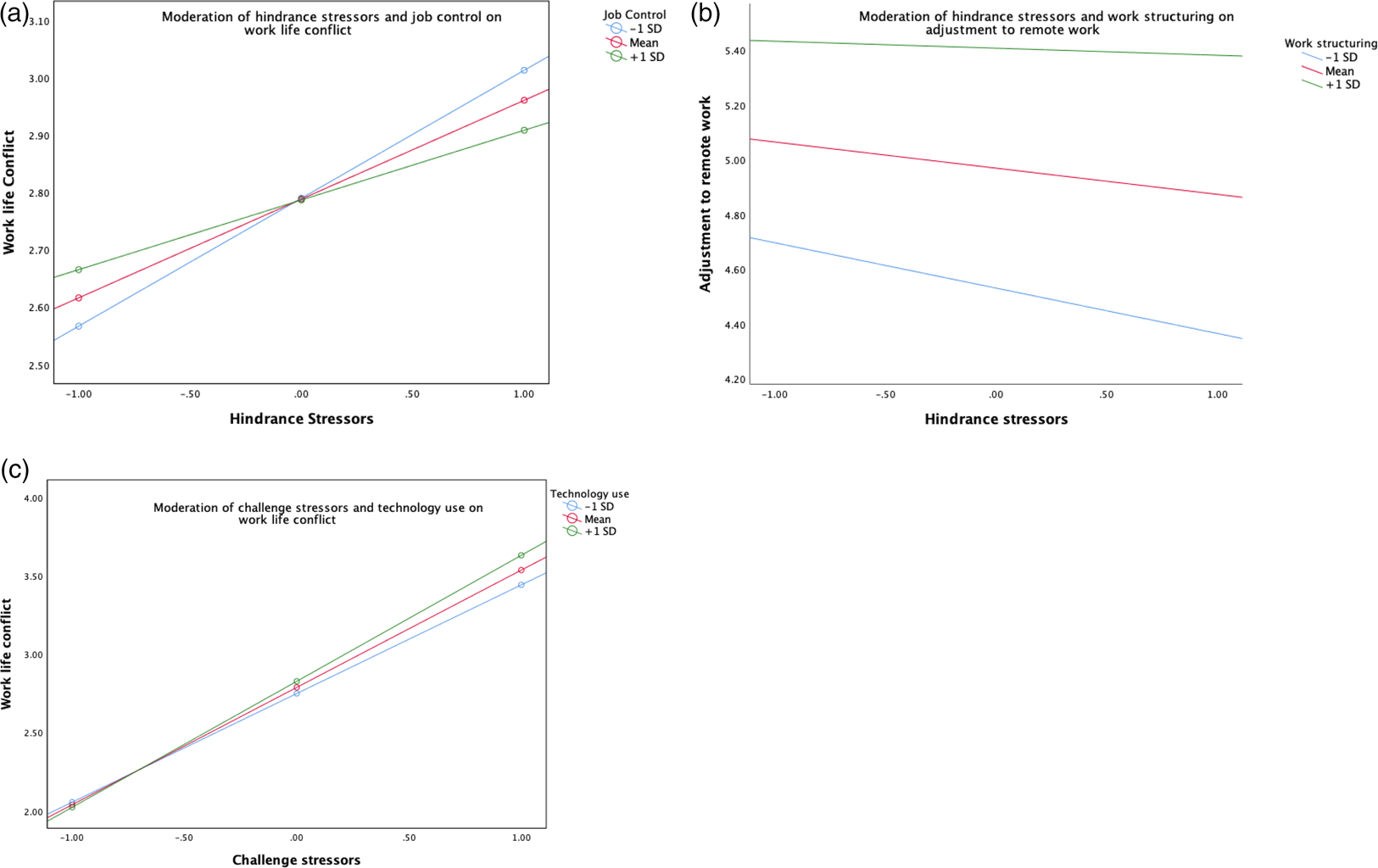

Moderations were probed when significant at least at p = .05. The three research questions address the potential buffering impact of job control, work structuring, and technology use. RQ1 investigated the role of individuals' job control in the relationship between stressors and support, adjustment, and work–life conflict. The results demonstrated that the relationships between hindrance stressors and work–life conflict is moderated by job control (B = −.11, 95% CI [−.202; −.012], p = .027). These results suggested that the influence of hindrance stressors on work–life conflict is less profound when job control was higher (see Figure 2a). There were no other interactions of job control with challenge or hindrance stressors.

Figure 2. Interaction plots. (a) Moderation of hindrance stressors and job control on work–life conflict. (b) Moderation of hindrance stressors and work structuring on adjustment to remote work. (c) Moderation of challenge stressors and technology use on work–life conflict.

RQ2 examined the role of work structuring. The results indicated that the only significant interaction was between hindrance stressors and work structuring in relation to adjustment to remote work (B = .08, 95% CI [.025; .134], p = .004). These findings indicated that hindrance stressors reduce adjustment to remote work especially when work structuring practices were low, rather than higher (see Figure 2b). There were no other significant interactions between stressors and work structuring.

Finally, RQ3 aimed to examine the moderating role of communication technology use. The results indicated that challenge stressors and technology use interact such that higher levels of technology use amplify the positive relationship between challenge stressors and work–life conflict (B = .09, 95% CI [.013; .172], p = .022). Figure 2c illustrates the moderation relationship at +1 sd, mean, and −1 sd.

Discussion

This study investigated work stressors and psychological strain during the initial stages of COVID-19 pandemic in Finland. Specially, the investigation focused on the mechanisms that inform the stressor–strain relationship in the context of remote work during the pandemic. In doing so, we respond to a recent call to examine the specific ways in which work stressors impact individual outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic (van Zoonen & Ter Hoeven, Reference van Zoonen and Ter Hoeven2021). Specifically, in response to the overarching research question presented in this study, the findings indicate that challenge stressors and hindrance stressors demonstrate a similar negative impact on adjustment to remote work, whereas hindrance stressors are more strongly negatively related to social support. Furthermore, we found that especially employees' adjustment to remote work diminished psychological strain (e.g., compared to the impact of social support), suggesting that well-adjusted remote workers experience less strain during the pandemic. The findings also show that both challenge and hindrance stressors are positively related to work–life conflict, with challenge stressors demonstrating a particularly strong positive relationship. Overall, we add to the challenge and hindrance stressor framework by presenting a more fine-grained analysis of the ways these stressors affect strain. For instance, the findings suggest that stressors experienced during the pandemic may lead to strain, especially because stressors are associated with lower levels of adjustment and higher levels of conflict. We discuss the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Theoretical implications

The findings of this study demonstrate that work stressors and psychological strain during the COVID-19 pandemic are related through several underlying mechanisms. First, we confirm the mediating role of social support in the stressor–strain relationship, demonstrating that hindrance stressors reduce perceptions of support. Social support, in turn, is important as it reduces psychological strain (Richardson et al., Reference Richardson, Yang, Vandenberg, DeJoy and Wilson2008). In doing so, this study presents evidence for notion that (hindrance) stressors are experienced as stressful and employees may feel their organization should do more to help them deal with these stressors. In line with Richardson et al., (Reference Richardson, Yang, Vandenberg, DeJoy and Wilson2008), our findings suggest that specifically hindrance stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic are perceived such that they are attributed to conditions that are (in part) controllable by the organization. Earlier work has demonstrated that employees may attribute a stressful work environment to a lack of support from the organization producing strain (Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002). This study adds that organizational actions (e.g., changing procedures and social distancing), whether controllable or not, may be perceived as an inability to facilitate support to help cope with work stressors (Gibson, Reference Gibson2020). This lack of support is problematic as support helps employees to reduce psychological strain. These findings connect with a growing body of research that more explicitly consider cognitive appraisals in understanding the underlying mechanisms of the stressor–strain relationships (e.g., Prem et al., Reference Prem, Ohly, Kubicek and Korunka2017; Tuckey, Searle, Boyd, Winefield, & Winefield, Reference Tuckey, Searle, Boyd, Winefield and Winefield2015). In response to examining how various stressors can have differential effects on work outcomes depending on whether they are appraised as hindering or challenges (Prem et al., Reference Prem, Ohly, Kubicek and Korunka2017), we explored how various factors (e.g., work–life conflict and lack of support) may operate as barriers affecting psychological strain. Future research could consider how cognitive appraisals inform these relationships.

Second, this study demonstrated that work stressors are negatively related to adjustment to remote work. Prior research on adjustment to virtual work had already established that structural work factors including independence and job clarity affect adjustment (Raghuram et al., Reference Raghuram, Garud, Wiesenfeld and Gupta2001). This study adds that both challenge and hindrance stressors impede adjustment to remote work, and importantly, this happens independently of job control. The findings presented very weak evidence for the buffering impact of individual's work structuring and job control on the implications of work stressors. The ability of employees to adjust is important as it reduces psychological strain. Theoretically, this links to research that often heralds contemporary job designs for their emphasis on anchoring job control (e.g., Bond & Bunce, Reference Bond and Bunce2003; Karasek & Theorell, Reference Karasek and Theorell1990). Literature on remote work in organizational and managerial studies has highlighted the importance of these aspects for employee motivation, performance, and other desired work outcomes (e.g., Kossek, Lautsch, & Eaton, Reference Kossek, Lautsch and Eaton2006; Meier et al., Reference Meier, Semmer, Elfering and Jacobshagen2008; Raghuram, Wiesenfeld, & Garud, Reference Raghuram, Wiesenfeld and Garud2003).

The findings of this study imply that job control was ineffective at buffering the impact of job stressors. Interestingly, respondents did not indicate very low levels of job control, hence, the findings may suggest that the specific nature of job control matters more. Future research may seek to understand the role of different aspects of job control for instance control over scheduling or work location, but also control over work methods, evaluation criteria, and other valued resources. This may be particularly relevant in situations that naturally limit aspects of control such as the COVID-19 pandemic. It should also be noted that although this may seem a unique setting, critical incidents are occurring frequently (e.g., economic downturns, natural disasters, terrorisms, and political turbulence) and remote work adaptation will continually challenge new and current employees as organizations seek sustainable job designs in global 24-h economies. Thus, it is important to identify individual-level buffers of job stressors on remote work adaptation, such as job control, and differentiate them from organizational buffers, such as social support, to understand their different impact on managing strain in times of such critical incidents and disruptions.

Third, this study demonstrated a clear link between challenge stressors (and hindrance stressors) and work–life conflict. These findings present empirical evidence for claims that that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates work–family conflict (Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020; Giurge & Bohns, Reference Giurge and Bohns2020; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020). As the global health pandemic unfolds, many employees are mandated to work from home rather than being able to select work modes and locations that align with the individual, organizational, and social needs, and preferences of employees. The findings confirm that the COVID-19 pandemic has further blurred the boundaries between work and social demands (Giurge & Bohns, Reference Giurge and Bohns2020) as work (especially challenge) stressors increase work–life conflict, regardless of household size.

Finally, the study presents a comprehensive investigation of hindrance and challenge stressors and how they relate to psychological strain in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated transition to remote work. We contribute to stressor–strain literature by demonstrating the importance of various underlying mechanisms that facilitate these relationships. Although the study aimed to provide insights into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on work, the results are important beyond the context of this pandemic. Research suggests that not only is the current crisis far from over (Hixon, Reference Hixon2020), future health crises of a similar nature are also almost guaranteed (Desmond-Hellmann, Reference Desmond-Hellmann2020). In addition, remote or multilocational work is increasingly common, requiring continuous adaptations to environmental demands and stressors.

Practical implications

The findings provide important insights for organizations and employees. Previous studies suggested that employees working from home during the pandemic ‘seem to be better off because they do not face increased infection risks and because they have a high discretion about how and when to do their work’ (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020, p. 9). However, this study demonstrated that employees may experience psychological strain due to work stressors experienced during the pandemic. The findings demonstrate that individual means, such as job control and work structuring only have a very limited buffering impact. Hence, organizations need to be wary of the daunting challenges employees face with trying to maintain some level of productivity, efficiency, and wellbeing in these trying times. Offering employees leeway in when and where work is conducted or helping them structure their workdays might not be enough to mitigate the negative impact of work stressors. The assumption that ‘because working from home often implies a higher-level autonomy, strain symptoms such as exhaustion may be lower’ (Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020, p. 9) does not seem to hold up in the context of this global health pandemic where remote working is more of a directive rather than a choice. The results demonstrate that especially adjustment to remote work is an important factor underlying psychological strain. Hence, organizational interventions could focus on helping employees make these adjustments. Directly actionable interventions include improving employees' work ergonomics and other contextual factors at home. Often employees work in improvised home offices, bedrooms, or at kitchen tables lacking adequate space, equipment, and materials to do their work in these unusual settings (Neeley, Reference Neeley2020; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020).

Second, the findings demonstrated a particularly strong relationship between challenge stressors and work–life conflict, arguably in part as restriction during COVID-19 also affected daycare facilities. This led many families to be at home trying juggle different demands including home schooling, work, and household tasks. Nonetheless, organizations can help employees by fostering a family friendly work culture (French, Dumani, Allen, & Shockley, Reference French, Dumani, Allen and Shockley2018), and by directly mitigating stress and strain by providing additional resources and reducing workloads. Recent studies have also suggested that communication between supervisors and subordinates about family demands help to reduce work–life conflict (van Zoonen, Sivunen, & Rice, Reference van Zoonen, Sivunen and Rice2020). Hence, managers and organizations should, especially in these times, facilitate conversations about family and broader social demands with organizational members. Indeed, many studies emerging on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic have argued that there is a pressing need to address the increased demands on work–life boundaries (Carnevale & Hatak, Reference Carnevale and Hatak2020; Kniffin et al., Reference Kniffin, Narayanan, Anseel, Antonakis, Ashford, Bakker and Vugt2021; Rudolph et al., Reference Rudolph, Allan, Clark, Hertel, Hirschi, Kunze and Zacher2020).

Finally, organizations have a fair amount of control over the hindrance stressors organizational members experience (Rodell & Judge, Reference Rodell and Judge2009). As hindrance stressors have a strong impact on perceptions of social support, organizations may focus on managing these stressors. For instance, it would benefit organizations to maximize their efforts to minimize unnecessary paperwork and clarify job expectations and security in these uncertain times. This could be done by clearly communicating about the organization's strategy for coping with the pandemic and how this strategy impacts individual workers and work processes.

Limitations and future research

Several limitations of the study need to be acknowledged. First, the study draws on cross-sectional survey data gathered through a convenience sampling method. This approach does not allow any claims about causality. Second, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic will vary between professions and occupational status (e.g., Kramer & Kramer, Reference Kramer and Kramer2020; Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020). For instance, employees with flexible or temporary employment contracts may be more strongly affected (Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020). Similarly, the current crisis has led to the segmentation of essential and non-essential work, or good and bad jobs (Kramer & Kramer, Reference Kramer and Kramer2020). Although the study includes a heterogenous group of Finnish employees, the data do not allow group comparisons for employees with different types of employment contracts (e.g., Spurk & Straub, Reference Spurk and Straub2020) or between those in the front-line (e.g., healthcare workers) and those professions that are labeled ‘non-essential.’ Further research may heed the calls from various scholars to further examine the impact of this health pandemic on workers from different professions, organizations, and with various occupational statuses. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that essential and non-essential workers may both experience mental health problems, but these may be triggered by different stressors (van Zoonen & Ter Hoeven, Reference van Zoonen and Ter Hoeven2021). Third, our sample was female dominated and further studies should address the gender differences. Fourth, the study is conducted in Finland in May 2020 around 2 months since lockdown with a specific social and cultural system, however, comparable to many other Northern and Western European countries. This specific context of study may prove to limit the generalizability of the findings to socio-political and economical systems that have a different orientation toward, for example, social security and occupational health. Future research is needed to examine how various combinations of contextual factors impact the stressor–strain relationships demonstrated here. Aside from structural equation modeling analysis, fuzzy-set-qualitative comparative analysis may provide such insights into complex and possibly contradicting cases (Woodside, Reference Woodside2013; Yueh, Lu, & Lin, Reference Yueh, Lu and Lin2016; Zhang, Reference Zhang2019).

Despite these limitations, this study provides insights into the stressor–strain relationships as experienced by employees working under a remote work mandate during a global health crisis. The findings suggest that organizations need to reconsider how they can support their employees in meeting the demands they need to cope with during the crisis. Based on our current understanding the focus on facilitating adjustment to remote work seems most potent in mitigating psychological strain.