INTRODUCTION

Settler colonisation involves the replacement of indigenous political, legal, economic and social institutions with settler ones, enabling territorial and cultural dominance (Reid, Rout, Tau, & Smith, Reference Reid, Rout, Tau and Smith2017). The primary mechanism by which this is achieved is the imposition of institutions by the settler state, for example, structures of government, law and enforcement (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2006). Consequently, indigenous inhabitants of settler colonies live in an imposed institutional framework that is foundationally biased against them. As Brett (Reference Brett1995: 207) explains, colonisation ‘marginalized indigenous structures and excluded local people from the management or regulation of the new ones’. This has and continues to cause a raft of negative outcomes for indigenous peoples.

Economically, settler colonisation was disastrous for indigenous people. Alienation from land – the fundamental resource base – forced indigenous people to join settler economies as dependents – structurally subordinate and often lacking the skills and capabilities to permit adaptation – causing material poverty (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Rout, Tau and Smith2017). Crucially, settler institutional frameworks are not just generally geared against indigenous people but are often incompatible with indigenous worldviews and scholarship shows the greater the mismatch between institutions and indigenous worldview the worse the economic outcomes (Cornell & Kalt, Reference Cornell and Kalt1995, Reference Cornell and Kalt2000).

This was the New Zealand Māori experience, after losing the majority of their land in the first decades of colonisation they remain overrepresented in negative economic indicators (Reid et al., Reference Reid, Rout, Tau and Smith2017). One example stands outside this experience: muttonbirding – the process of harvesting and selling tītī (muttonbirds) and the surrounding tikanga (customs). This paper will use muttonbirding, including interviews with 20 Ngāi Tahu ‘birders’, as participants who ‘bird’ are known, to examine how the contemporary institutional framework constrains indigenous entrepreneurship by contrasting pre- and post-contact political, legal and economic institutions. In other words, entrepreneurship is the vehicle that will enable the examination of the way past and present institutions constrain the tītī economy, guided by the insight that culturally-matched institutions generally deliver better economic outcomes. After providing an overview of the tītī economy, it will offer a definition of indigenous entrepreneurship, followed by an outline of institutional economics, which will enable the development of an analytical framework. Then, after explaining how the interviews were gathered, this framework will be used to examine the role institutions play in constraining entrepreneurship in the tītī economy as guided and illustrated by participant statements. Finally, the key finding that the loss of executive authority, the high chief, has constrained contemporary entrepreneurship because it has limited ability, restricted opportunity and restrained innovation, will be examined.

MUTTONBIRDING

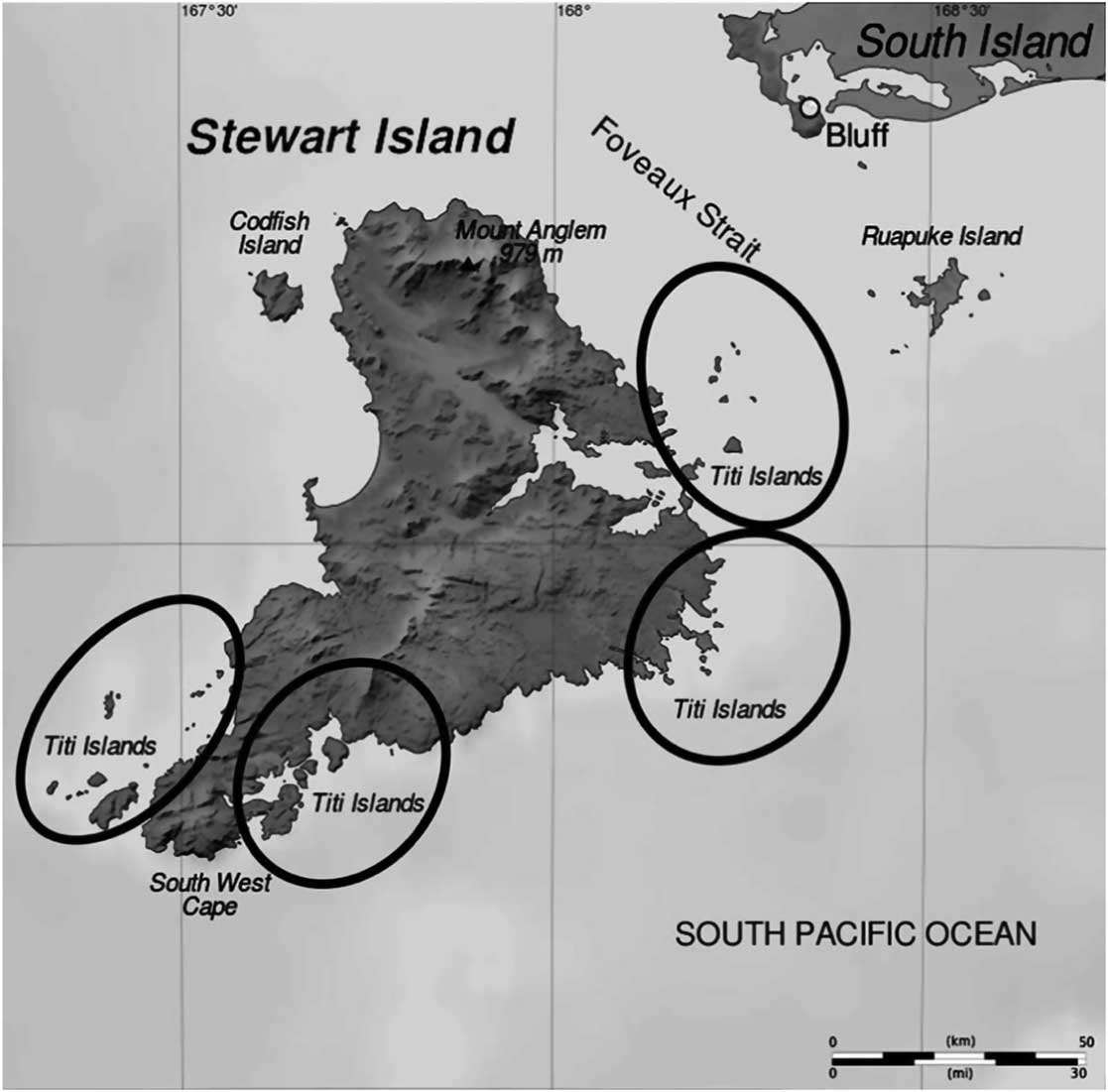

Ngāi Tahu, a Māori tribe from the South Island of New Zealand, have been harvesting the pelagic tītī chicks for many centuries across numerous small, isolated ‘Tītī Islands’ near Rakiura (Stewart Island, New Zealand’s third largest island) (Kitson, Reference Kitson2006). While the exact nature of pre-contact tītī harvest is debated, by the protohistoric period it was a sizeable operation (Anderson, Reference Anderson1980). Numerous reports from Europeans around Rakiura in the early 19th century attest to large numbers of birders and tens if not hundreds of thousands of birds preserved and ready to be distributed through various kin/trade networks (Anderson, Reference Anderson1980, Reference Anderson1997; Williams, Reference Williams2004; Stevens, Reference Stevens2006).

In the pre-contact and protohistoric periods, the tītī economy was politically, economically and socially important, and when the Crown was negotiating the purchase of Rakiura in the mid-18th century, the local Māori ensured some Tītī Islands (hereafter: the Beneficial Islands) were reserved for harvesting. This alone is remarkable as the harvest remains one of the last of its kind around the world, enshrined in settler state laws where most other indigenous customary rights were extinguished by these same institutions. However, not all of the Tītī Islands were reserved for harvest, nor were all the people who had the ancestral right to harvest listed on the 1864 Deed of Cession (Williams, Reference Williams2004; Stevens, Reference Stevens2006). This created numerous problems and in 1912 the islands not listed on the Deed (hereafter: the Crown Islands) were (legally) opened up by the Crown to those who had the right to bird through whakapapa (genealogy) but had been left off the Deed (Kitson & Moller, Reference Kitson and Moller2008). As part of the wider Treaty of Waitangi settlement that saw reparations paid for grievances during colonisation, these Crown Islands were returned to Ngāi Tahu, or more specifically the tribal governing council Te Runanga o Ngāi Tahu or the Ngāi Tahu tribal council, which is composed of 18 Papatipu Runanga (regional councils). The Figure 1 given below shows Rakiura and the location of the Tītī Islands, though it should be noted the Beneficial and Crown Islands are not geographically distinct regions.

Figure 1 Original map, © Sémhur/Wikimedia Commons/CC-BY-SA-3.0, adapted by authors

As well as the many political and legal issues birders have experienced over the past 150 years, muttonbirding has been dramatically impacted by Ngāi Tahu transitioning from hunter-gathering into the capitalist market economy and by advances in technology, with birders now taking helicopters rather than paddling waka (canoes). Still, as many have concluded, the practice of muttonbirding remains a core expression of cultural identity for those who practice it and is seen as a central pillar of whānau (family) cohesion and tribal economic and social autonomy (Dacker, Reference Dacker1994; Taiepa, Lyver, Horsley, Davis, Brag, & Moller, Reference Taiepa, Lyver, Horsley, Davis, Brag and Moller1997; Williams, Reference Williams2004; Stevens, Reference Stevens2006; Kitson & Moller, Reference Kitson and Moller2008). Furthermore, while technology has changed much, the basic birding process remains similar to pre-contact. The season lasts for around 2 months, seeing fledgling chicks a few months old gathered in two particular phases – in their nest-holes first, then above ground. Each chick is processed on the island, generally being plucked, salted, then placed into a bucket of between 10 and 20 birds, ready to be taken back to the mainland for distribution. While information is hard to acquire for the tītī economy as a whole and varies vastly depending on season and birder, buckets sell for between roughly $NZ 200–500, our participants talked about individually getting 25–75 buckets as a good season and the overall tītī economy averages between 60,000 and 120,000 buckets annually.

INDIGENOUS ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Entrepreneurship remains a contested concept with no agreed upon definition, though many mention displaying novelty, showing ability and seizing opportunity to accumulate capital as core aspects (Davidsson, Reference Davidsson1991; Shane & Venkataraman, Reference Shane and Venkataraman2000; Iversen, Jørgensen, & Malchow-Møller, Reference Iversen, Jørgensen and Malchow-Møller2007). While we will use these parameters, they need to be framed specifically for indigenous entrepreneurship, both to avoid this definitional confusion and because, as Dana (Reference Dana2007: 3) notes, ‘the culture of indigenous people is often incompatible with the basic assumptions of mainstream theories’.

Anderson, Honig and Peredo (quoted in Tapsell & Woods, Reference Tapsell and Woods2008: 193) provide a useful definition of indigenous entrepreneurship as ‘the enterprise-related activities of indigenous people in pursuit of their social/cultural self-determination and economic goals’; that is, combining western economic goals with indigenous socio-cultural motivations. Quoting Roberts and Woods, Tapsell and Woods (Reference Tapsell and Woods2008: 195) define an ‘economic entrepreneur as a creative and active player in the market process’, then explain that social entrepreneurship ‘is the construction, evaluation and pursuit of opportunities for transformative social change carried by visionary, passionately dedicated individuals’. They go on to explain that indigenous entrepreneurship needs to bring these two together in balance, focusing on both economic aims and social goals simultaneously. This is a key insight. Hindle and Moroz (Reference Hindle and Moroz2010: 361 – emphasis in original) write that ‘[i]f Indigenous entrepreneurship is to be a field, it must retain the parent discipline’s emphasis on novelty’, then note most definitions ‘stress the importance of new economic enterprise’. However, we believe that newness must be tempered by respect for core indigenous institutions and that the key to indigenous entrepreneurship is balance between economic novelties and social growth. As Tapsell and Woods (Reference Tapsell and Woods2008) note, innovative risk-taking in Māori society is moderated by conservative risk-management. Furthermore, as our focus is on a traditional economic enterprise, one where ability and opportunity have been impacted since colonisation, we feel that focusing on innovation at the expense of other entrepreneurial aspects would do a disservice to our analysis.

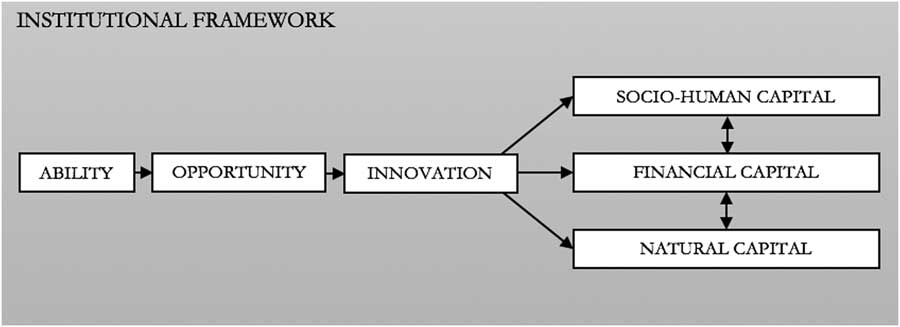

With this in mind, indigenous entrepreneurship here is seen as the application of ability to an opportunity with the aim of increasing capital through innovation. Ability is an individual or group’s innate qualities (e.g., capabilities) to take advantage of opportunity and innovate. Opportunity refers to a situational potentiality to increase capital through the application of ability to innovate. In our definition, capital refers to different forms of wealth. ‘Financial capital’ refers to money. ‘Socio-human capital’ is used to refer to both social and human capital; that is, not only people’s knowledge, skills and motivation – human capital – but also the networks which help maintain human capital such as families, communities and so forth – social capital. We also consider a third form, ‘natural capital’, that is all the world’s natural resources, as in the Māori worldview it is impossible to disentangle culture (the social and economic) from nature (the environment) (Reid & Rout, Reference Reid and Rout2016a). Innovation is seen as applying to all three forms of capital. Financial innovation is the creation of new products and the marketing of these. Social innovation involves new institutional structures and practices. Natural innovation includes development of sustainable initiatives. Thus, we see indigenous entrepreneurship as applying ability to opportunity to increase indigenous financial, socio-human and natural capital through innovation.

INSTITUTIONAL ECONOMICS

For North (Reference North1990: 3) institutions are ‘the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, are the humanly devised constraints that shape human interactions’ and can be either formal (constitutions, laws, etc.) or informal (norms, customs, mores, traditions, etc.). The dominant neoclassical school of economics ignores the role of institutions because it believes markets are shaped by ‘instrumental rationality’ and that political, legal and cultural contexts have little impact on economic interactions (North, Reference North1990; Brett, Reference Brett1995). It is premised on ‘a world of self-interested but law abiding and socially responsible individuals who choose freely between competing alternatives on the basis of perfect information’ (Brett, Reference Brett1995: 204). While this has some fidelity when examining modern capitalist economies, it is problematic when analysing socially-embedded indigenous economies (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985). Institutional economics offers the best analytical tool.

Institutional economics is premised on the understanding that institutions ‘structure incentives in human exchange, whether political, social, or economic’; in other words, ‘institutions define and limit the set of choices of individuals’ (North, Reference North1990: 3, 4). This is intuitively obvious, an entrepreneur in North Korea faces a different set of institutional constraints to one in New Zealand. Where the neoclassical school assumes institutions develop to meet a society’s economic needs in a logical manner, institutional economics understands that the institutional framework develops in a far more chaotic manner and imposes a number of transaction costs on exchanges, such as the cost of a legally required contract (Brett, Reference Brett1995). Williamson (Reference Williamson2000) identifies four interacting levels of institutions, the highest is social embeddedness, taking in the norms, customs, mores and traditions, the next level down is the ‘formal rules of the game’, such as laws, the third level is the ‘play of the game’, including contracts, and finally the bottom level is the market, where the exchange of goods and services is regulated by supply and demand. These levels can be broadly generalised as encapsulating, from highest to lowest, social, political, legal and economic institutions (Azfar, Reference Azfar2006). However, from an indigenous perspective it would be more accurate to think of the last three as embedded in and emerging from the social: political, legal and economic institutions are inherently social in nature (Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985). Hence we will only examine political, legal and economic institutions.

ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

Merging our understanding of indigenous entrepreneurship with institutional economics provides the analytical framework: political, legal and economic institutions are understood to constrain opportunities for indigenous entrepreneurs, their ability to realise them and their capacity to innovate. Consequently different types of institutions can foster or hinder entrepreneurial activity and in turn the generation of financial, socio-human and natural capital. The dynamics are outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Analytical framework mapping indigenous entrepreneurship dynamics

The focus, then, will be on examining how the political, legal, and economic institutions, and particularly changes since colonisation, have constrained or enhanced abilities and opportunities to increase socio-human, financial and natural capital through innovation. The paper will outline the three institutional domains individually, focusing on a key theme for each, before examining how they constrain entrepreneurship as a total institutional framework.

POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS

The defining theme for political institutions is ‘authority’: the power or right to issue orders, make decisions and enforce obedience. Authority in pre-contact Māoridom was reciprocal and dependent rather than an absolutist hierarchy (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2003). While hapū (sub-tribes) were the most dominant socio-political grouping (Ballara, Reference Ballara1998), on the Tītī Islands whānau elders had authority, playing ‘a strong role in the decision-making and harvest practices on their particular island or manu [birding territory]’ (Moller, Kitson, & Downs, Reference Moller, Kitson and Downs2009: 251). Furthermore, Anderson (Reference Anderson1980) argues that tītī were so valuable and localised this resource enabled the tribe Ngāi Tahu to maintain a hierarchical tribal structure despite not practicing agriculture, a theory that Stevens (Reference Stevens2006, Reference Stevens2011) and Williams (Reference Williams2004) reinforce. As Anderson (Reference Anderson1980: 15) states, the ‘operation of this system for the distribution of such a valuable commodity would, it is suggested, have provided the necessary background for the development, or the maintenance, of a tribal chiefdom’, with the high chief most likely acting as ‘the arbiter of birding rights and the foremost broker in a mutton bird exchange’. It was no coincidence, Anderson (Reference Anderson1980) argues, that Ruapuke Island, near Rakiura, served as the Ngāi Tahu high chief’s main residence and the centre of muttonbirding rights adjudication and exchange. There was, then, a division between ‘operational’ authority at the whānau scale and ‘executive’ authority at the iwi (tribe) scale. Whānau elders had relative freedom on their island but the high chief had authority to determine birding rights and to regulate tītī exchange. This authority dynamic is crucial to understanding the contemporary situation, not just its functions but also the way in which it would have been understood and accepted by the tribe as the roles of, and interactions between, the operational and executive authority were embedded within tikanga. In short, the roles of authority and their power dynamics were well-defined and would have been widely accepted by all birders (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2003).

With regard to the contemporary situation, generally speaking, whānau elders still have operational authority (Moller, Kitson, & Downs, Reference Moller, Kitson and Downs2009). There are, however, new and complex power dynamics at the executive level, with a committee for both Beneficial and Crown Islands, Ngāi Tahu tribal council and the Crown all having differing powers. After numerous legislative changes that have seen authority shift several times, there are now two committees that ‘administer’ the Beneficial and Crown Islands, which in practice means they have assumed the executive authority to adjudicate on rights, pass by-laws and enforce tikanga on the islands. However, their executive authority is not absolute, as the Crown, through the Māori Land Court, also adjudicates on rights for both Beneficial and Crown Islands. As the 1983 Māori Purposes Act that vested title in the Beneficial Owners outlined, the Māori Land Court (Māori Land Court, 2013: 1028) retains ‘exclusive jurisdiction to determine relative interests and succession to such interests of deceased owners and appoint trustees for persons under disability in respect of the beneficial ownership of the islands’. The Ngāi Tahu tribal council has no official authority over the Beneficial Islands, but were given the title to the Crown Islands in 1998, are required to manage these islands ‘as if they were nature reserves’ (Taiepa et al., Reference Taiepa, Lyver, Horsley, Davis, Brag and Moller1997: 244). There is, then, no single executive authority for rights adjudication and none of the various executive authorities have any power or capacity with regard to regulating exchange.

LEGAL INSTITUTIONS

The key theme for legal institutions is ‘rights’: the entitlement to have or obtain something. Generally speaking, pre-contact rights were layered, dynamic and, consequently, complex (Williams, Reference Williams2004). Māori did not ‘own’ land but rather had an array of user rights that were largely defined by resources (Reid & Rout, Reference Reid and Rout2016b). As a prized commodity, tītī were governed by strict user rights as delineated along whakapapa lines, though this was not an absolute genealogical right but rather had to be retained through ahikā (continued usage) and ultimately could be given or taken away at the high chief’s discretion (Williams, Reference Williams2004). While these rights were utilised collectively by the whānau, ‘[f]rom the position of the family, these manu belonged to the family elder with rights’ (Tau, Reference Tau2016: 684). The right was not absolute, however; it could be lost through lack of exercising it and by the high chief’s adjudication, implying he would have used mana (power/prestige) – as well as whakapapa and ahikā – as a metric to grant or deny rights. Crucially, mana has three sources: ‘mana atua – God given power; mana tupuna – power handed down from one’s ancestors; and mana tangata – authority derived from personal attributes’ (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2003, para. 15). Mana’s tripartite nature ‘explains the dynamics of Māori status and leadership and the lines of accountability between leaders and their people’ (Gallagher, Reference Gallagher2003, para. 15). A loss or gain in mana tangata would result in the equivalent gain or loss of authority, it functioned as the meritocratic stabiliser against inherited status. Anderson (Reference Anderson1998: 100) explains that ‘Ngai Tahu liked to avoid dynastic aspirations by balancing the mana conferred by whakapapa with that acquired by service’. Historically, the ‘islands were divided into different areas (manu) for each family to work’ (Tau, Reference Tau2016: 684) ‘so that each whakapapa group had their share, and [the manu] were exploited by entire family groups’ (Williams, Reference Williams2004: 149). Tau (Reference Tau2016: 684) quotes an elder at a Native Land Court hearing in 1887 explain that the island Papatea (Green Island) ‘was divided into sections and names after certain ancestors’. The preciousness of the resource and the resultant surety of who held rights suggest the rights configurations were fairly well-defined.

The intervening 150 years has seen much confusion and contention over who has rights (Stevens, Reference Stevens2006; Kitson & Moller, Reference Kitson and Moller2008). This has been largely overcome and the core whakapapa-based nature of rights remains for both Beneficial and Crown Islands. For the Beneficial Islands, the right belongs to the whānau elder and is passed on upon death, while the right to bird on the Crown Islands requires proof they are ‘Rakiura Māori’; that is, they whakapapa ‘to the harvesters present when the 1912 regulations were promulgated’ (Kitson & Moller, Reference Kitson and Moller2008: 161). The flexibility of how they gain these rights has changed, however. For the Beneficial Islands succession has become more fixed in nature. Where once there was mobility through changes in mana the rights are now determined solely by whakapapa. Conversely, for the Crown Islands rights have become more fluid. Now those Rakiura Māori without a beneficial right must apply for a permit every year (Kitson, Reference Kitson2006). This has resulted in a disruption of continuous connection that defines ahikā and a consequent decline in traditional knowledge and protocols that have guided the exercise of ahikā rights. As a result of the loss of a clear executive authority and the ongoing issues regarding who has rights, the geophysical configuration of the rights has become less clear on many islands ‘that hitherto had distinct manu, no longer do so’ and, consequently, have ‘witnessed a shift from pockets of self-interested kaitiakitaka [guardianship] to a tragedy of the commons type race to the bottom’ (Stevens, Reference Stevens2011: 28).

ECONOMIC INSTITUTIONS

The key theme for economic institutions is ‘exchange’: the mechanism through which goods and services are transferred. The Māori pre-contact economy was largely based on reciprocal exchange (Firth, Reference Firth1972). Reciprocity, however, can be divided up in a number of ways (Sahlins, Reference Sahlins1972). Here it is useful to think of two spectrums. One spectrum delineates the main driver of the exchange, with utilitarian ‘barter’ at one end and ‘gifting’ as a form of social obligation at the other. The second spectrum is focused on the group dynamics, with the hierarchical and centralised ‘redistribution’ exchange within a group at one end and the flat inter-group ‘disbursal’ exchange at the other. With regard to tītī exchange, it is likely that the high chief used redistribution within Ngāi Tahu and a mixture of barter and gifting regulatory exchange with other iwi (Anderson, Reference Anderson1980; Williams, Reference Williams2004; Stevens, Reference Stevens2006). Critically, while it is unlikely the high chief controlled the total supply of this precious resource, with Stevens (Reference Stevens2006) and Williams (Reference Williams2004) both outlining barter and gifting exchanges of tītī between Ngāi Tahu hapū, Anderson’s (Reference Anderson1980) convincingly argued position suggests that high chief’s executive authority enabled them to control much of the exchange in a way that was not just personally beneficial, but beneficial to the whole tribe. Thus, the pre-contact means of exchange was largely embedded in social relations, though still had a utilitarian component both internally and externally, and was tied in with political authority, which played a regulatory role.

The post-contact tītī economy has become increasingly dominated by market exchange (Dacker, Reference Dacker1994; Williams, Reference Williams2004; Stevens, Reference Stevens2006). As early as 1844, Wohlers (quoted in Stevens, Reference Stevens2006: 282), noted that ‘a large quantity of these mutton birds’ were sent north, with birders ‘receiving for them in exchange either money or money’s worth in flour, sugar, and such like’. While personal and whānau-located barter and gifting, to differing degrees, have remained as forms of exchange, the high chief’s loss of authority has seen the traditional internal redistribution and external regulation disappear, with whānau elders selling tītī directly to market (Dacker, Reference Dacker1994; Williams, Reference Williams2004; Stevens, Reference Stevens2006). Small scale barter and gifting exchange still remain important parts of the tītī economy; however, traditional redistribution and disbursal forms of exchange are less likely to survive in a market economy as they are incompatible – given that the former are premised on centralised control and the latter on decentralisation (Nee, Reference Nee1996). That market exchange would come to dominate is unsurprising as birders have become fully enmeshed in the wider settler economy, needing money for life off the island and to purchase birding supplies and transportation. Where once the exchange was largely socially-defined and intrinsically connected to authority structures, it is now largely an unregulated utilitarian exchange of a commodity for cash.

METHODOLOGY

The research involved 20 interviews with birders from both the Beneficial and Crown Tītī Islands. The interviewees were questioned about the institutions in which the birders operated, and the extent to which these institutions expanded, or contracted their ability to realise opportunity, innovate and generate socio-human, financial or natural capital. The interview process was informed by the Kaupapa Māori research methodology, which emerged through the works of Māori scholars including Graham Hingangaroa Smith (Reference Smith1997), Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Reference Smith1999) and Leonie Pihama (Reference Pihama2010). Kaupapa Māori emphasises processes that respect and give voice to indigenous knowledge systems and place control of the research process collectively in the hands of Māori (Smith, Reference Smith1999). Consequently, we used two Rakiura Māori interviewers to conduct ten interviews each with birders from their own whānau and hapū networks. The interviews were guided conversations that focused on gathering data through personal story-telling, a method based on the Māori practice of ako, where narrative is used to support learning processes (Lee, Reference Lee2008). The interviews explored the institutions underpinning the tītī economy and were analysed with a focus on the three core themes – authority, rights and exchange – which were then examined with respect to how they enhanced or constrained ability, opportunity and innovation. To ensure candidness, birders remain anonymous and will be referred to by a randomly selected number between 1 and 20, as well as whether they bird on the Beneficial or Crown Islands. Finally, in keeping with Kaupapa Māori principles we consulted with the interviewers to ensure selected statements retain context and have overarching validity with the interviewees’ perspectives.

HOW THE INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK CONSTRAINS AND ENCOURAGES ENTREPRENEURSHIP

As should be clear, the institutional components discussed above cannot be considered in isolation, but rather together as an overarching framework that constrains or encourages ability and opportunity to increase capital through innovation. It is apparent from the historical record and the interviews conducted that there are several interrelated constraints on increasing capital in the tītī economy, which all flow from the loss of a singular executive authority and its centralising and collectivising role across exchange, rights and other areas.

Critically, without an executive authority regulating exchange birders have lost the ability to control supply in relation to demand within the market. There is significant demand for the birds; however, it was evident that birders were undercutting each other when selling to traders, driving a ‘race-to-the-bottom’ and, critically, reducing already small margins. While some birders still have regular buyers, others told us that the open market was problematic:

… I price my birds according to what it’s cost me to actually harvest them. Some people sell their birds very cheaply and then I lose a whole bunch of sales to cheaper birders who [undercut me]… [#11-Beneficial]

At times prices of tītī can stay the same for quite a number of years which is governed a lot by the costs involved. I believe… they’re under-priced, they should actually be increasing the costs every year to cover themselves… I think there is maybe some people get pressured on money and adjust their prices… you do hear of people say well so and so has sold some birds for whatever and you’ll pick up that its quite below of what others are getting. But some people too are dictated by the market in regards to who they use, are forced to come down. [#12-Crown]

It appears the loss of executive authority has constrained birders’ opportunity to increase financial capital as they undercut each other rather than collectively regulating supply, as the high chief did traditionally. Furthermore, the results suggest that those profiting are external traders who are able to seize the opportunity because they have the financial capital to amass enough product to control supply. We were told by birders about non-birder middlemen profiting:

There is big buyers out there that will buy them and then take the up north and that. Like they’re buying 100 buckets… [#8-Beneficial]

[One buyer] must get at least 30,000 or 40,000 [birds] and they’re gone as soon as they hit the wharf in Bluff… [#4-Beneficial]

Furthermore, while there is demand for the birds, many birders struggle with the variability across seasons, as they explain:

You get probably one season that doesn’t cover anything but you have other seasons that may cover your bills. [#6-Beneficial]

The markets aren’t that easy. I mean it depends on the season. [#8-Beneficial]

…you can make some money but then again it will all come down to how good your muttonbird season was. [#16-Beneficial]

Crucially, none of the executive authorities in place today have the power to regulate exchange. A return of executive authority in relation to the market would also increase financial capital by enabling birders to enhance opportunities through regulating supply. Not only could the executive authority ensure birders did not undercut each other but it could also prevent middlemen from ‘clipping the ticket’ whilst also balancing out seasonal supply differences. While phrased differently, the need for executive regulatory power that comes from the collective working together and would help overcome bad seasons was apparent in this birder’s statement:

If we used our traditional values of being a whānau group or a co-op or something around that nature I think we could do better… That’s probably the saddest thing about the whole muttonbirding thing for me is that we aren’t a little bit more of a collective as far as that goes. We inevitably work really really hard some seasons and we get no return out of it. [#11-Beneficial]

Interestingly, from this statement the possible hybridity of any executive authority can be inferred, as they refer to both ‘traditional group values’ and a ‘co-op’. This would represent social innovation, creating an amalgam structure better suited for the contemporary era than a precise recreation of pre-contact authority. The present political institutional structure is constraining financial innovation, most birders are pressed just to stay solvent. For example, when asked how the Ngāi Tahu tribal council could help, a birder told us:

A website for selling them would be a big thing for them. Getting people out there that want to buy them to connect with the people that are selling them. [#8-Beneficial]

Running a collective sales website would be an innovative way for the executive authority to regulate supply and it could also increase demand. Premium online sales are difficult for individual birders, however, as one who had been selling on New Zealand’s main online customer-to-customer sales platform told us:

… I’ve always endeavoured to maintain the quality of my birds so I can justify whatever price I’m asking for. I hope that that would be a point of difference but it hasn’t really helped me over the years. [#11-Beneficial]

The reason for this is that in the contemporary online era trust must be established through verified entities (Reid & Rout, Reference Reid and Rout2016b). The lack of executive authority is inhibiting financial innovation because birders are unable to project authenticity online on their own. Another means of ensuring higher prices through the executive authority would be some form of provenance quality control. There is a market for high-quality product, one birder explained that:

… if we know there’s birds we have a look out the back and look at the brand, “Oh nah, nah, I’m alright thanks [I don’t want to eat their birds].”… they’ve all got the brands on so everyone knows whose birds are whose. [#1-Beneficial]

Provenance quality control also has potential to increase natural capital as it focuses on producing smaller amounts of high end product. As one birder explained:

I’ve seen some muttonbirds… only fit for pate… the quality is not there, the focus is not on the quality it’s on how many we can get. It doesn’t apply to everybody but there are certain ones down there they have to relook at what their product and what they’re doing and why they are there for and it’s not kill everything in sight and shove them in a tin and sell them. [#16-Beneficial]

A second role for the executive authority could be lowering production costs so that prices could be maintained at a level that meant while birders recouped expenses they were not pricing the birds out of the market. The birders have experienced significant rising operational expenses year on year, as they expressed:

I think economics kills a lot of people from going to the island because it is quite expensive to go there. [#8-Beneficial]

… it’s costing so much to go down there now… so many different factors now that didn’t apply in the old days so that has added a lot of pressure on the way people do things now. [#16-Beneficial]

… the expense factor is quite phenomenal as the years go by inflation it just keeps raising the bar and the price of muttonbirds don’t really, sometimes really don’t go hand in hand with it. Our costs over the years we have just sometime just made it, we have covered our costs. [#17-Beneficial]

Acting as individual operators, each whānau group on its own lacks economies of scale to purchase the necessary supplies at a ‘trade rate’, paying full market value. An executive authority could provide that scale, reducing the cost of supplies. They could also help lower the cost of transportation, usually via boat and helicopter. This was commented on by a number of birders:

… it would be nice if there was a boat of some sort that could be owned by the tribe… [#10-Beneficial]

A Ngāi Tahu boat would be really good… [#6-Beneficial]

…if they had a big boat they could do two or three islands per trip and it could save quite a bit of money…[#14-Crown]

We have always talked about why doesn’t Ngāi Tahu have a boat and why not have a helicopter and ferry their people. [#17-Beneficial]

Ensuring birding remains financially viable requires both market regulation and supplies and logistics consolidation and coordination as there is only so much room for price increases before the market becomes unsustainable. As the birders explained:

… over the last few years people who used to buy birds are no longer able to afford them. [#11-Beneficial]

I don’t think people realise what it actually costs to do one bird. That one bird and if you priced it out could be very expensive and I look at it in the sense that you’ve got to keep at a realistic price for the families… I’d like to see the price a bit higher but then you’ve got to go within the people’s budgets and what a realistic price for doing it… You’ve got to get a reasonable price for your birds but yea I don’t know how far the price will go. [#14-Crown]

A third role the executive authority could play would be to facilitate innovation by encouraging communication amongst birders. Historically birders all travelled to Ruapuke Island first, now they go straight to their island. Thus, indirectly, the loss of executive authority has also reduced the capacity for birders to communicate with each other, limiting their ability to bird by constraining innovation. The importance of communication as a means of enhancing ability was emphasised to us by several birders:

… there is just no communication. Like you only have communication with the whānau that you know and that’s it. When the university was doing their research they produced Tītī Times which was a really pragmatic way of keeping birders in touch with each other. I just would love to see that reinstated; some sort of annual communication that came out say around about December/January, somewhere there where people are starting to get it in their minds again that they’re going birding. [#5-Beneficial]

At times for that wider information, that would be good to encourage [communication] so that people can all understand together… Inform people of what is happening in the wider world and how we can help ourselves…[#13-Crown]

The executive authority could also help birders develop new products, encouraging innovation. As one told us:

Obviously there’s a number of whānau that vacuum pack birds and I think that’s great; I’d like to do that myself and I can see how that can add a lot more value to the birds… And the by-products; we’re wasting a lot of the bird… obviously the hinu [muttonbird oil] and the feathers; we need to be doing more of that. I think it’s creating opportunities for whānau… through wānanga [learning seminar]… [we need] some kind of get-together outside of the season… [#10-Beneficial]

As this birder notes, innovative products and processing would ‘create opportunities’; however, as was clear across the interviews most birders struggle to maintain the status quo, let alone devote time to developing new products and novel processing methods to increase financial capital. An executive authority could devote time to development and could convene wānanga that enabled birders to share their innovations.

Fourth, the executive authority could also help with innovative sustainability initiatives, ensuring opportunity is not reduced by increasing natural capital, and helping improve ability by coordinating sustainability education. As the birders explained:

… perhaps it needs to come from the administering body… I think in the future it would be wise if we could have someone who is working out in the world [explaining] what is happening with pollution and the oceans and anything related to care of the seabirds as a whole, because that’s all part of our lives as well so I think information is a great thing so the people are kept informed… there needs to be opportunity to come together as one not as separate islands. [#13-Crown]

I would like to see that everyone on the island has to… make a tally of what everyone’s caught, every year… tally it up and somebody so they know and then you can see over the years how it is declining…Then you compare those trends with what’s going on with El Nino and all the rest of it and maybe that correlates. [#20-Beneficial]

… we need to be coming together as a community to create these adaptive plans in preparation… to say what can we be doing for the habitat?… Because if it’s a poor season we may put out more information to say, “Don’t come. Have a year off because there’s not many birds here.” And how we communicate that information across the community I think that can be really beneficial. [#10-Beneficial]

These suggestions appear to blend Māori and western approaches, including rahui (bans) and data gathering, in a novel manner. Just as with financial innovation, birders currently struggle to organise natural innovation – the executive authority would be able to coordinate novel sustainability practices. The sustainability education role of the executive authority would also help to increase socio-human capital by enhancing whanaungtanga and exchanging mātauranga Māori as well as helping individuals reconnect with their cultural identity.

Fifth, the executive authority could also advocate to the Ngāi Tahu tribal council and the Crown on behalf of birders, particularly with regard to issues of natural capital. For example, many of the birders are worried about the impact of the krill and squid fisheries on tītī numbers:

We always worry about the cycle of life with the fisheries, besides when the squid boats came, and now they’re taking krill for oil supplements. That is something that the birds feed on and the birds feed on squid… [#7-Beneficial]

… there was… one of those big boats down there fishing for krill and they were taking all the krill and sure enough there was no muttonbirds…[#19-Beneficial]

… maybe Ngai Tahu is involved I don’t know but we shouldn’t be trawling for krill so Ngai Tahu should do something about that … stop the krill and that will bring the muttonbirds back. [#20-Beneficial]

Ideally an executive authority would regulate supply, ensure provenance and quality, reduce operational costs, facilitate communication, encourage new product and packaging development, maintain sustainability and advocate on behalf of birders. This would likely create more opportunity for birders to apply their ability and generate financial, socio-human and natural capital through innovation. However, who or what exactly this authority should be is a contentious issue. A number of birders, particularly from the Beneficial Islands, made it clear they would not want the Ngāi Tahu tribal council in this role:

…it’s always upon Ngāi Tahu to remember you don’t own it, the whānau own it, the whānau lead and guide even though you’re facilitating and they have all the legal minds, but they have to be at our disposal of the whānau rather than then pushing or not understanding where the authority lies. The authority lies with the one who holds the right. [#3-Beneficial]

… it really needs to be grassroots; it has to start right at the very base of things because people won’t accept a top down approach on this… there can’t be a top down approach here. People are too protective of it. [#5-Beneficial]

… we were unhappy that our Tītī Crown Islands were put into Ngāi Tahu hands… why does Ngāi Tahu want our islands? Why do they want to help administer support… It’s all been a grey area for us. [#7-Beneficial]

… well hopefully [the tribal council are] not involved because we don’t need outsiders telling us the owners what to do on our property, we know what’s best for ourselves and the island…[#19-Beneficial]

Therefore, birders themselves need to create an entity that can provide different executive functions, with committees as the most obvious template, or source of personnel. The empowered committee/s would likely combine traditional Māori and western institutions in an innovative hybrid form. As one of the birders above suggests, a cooperative might be appropriate as this would ensure operational autonomy whilst providing executive functionality.

Contemporary rights issues, a consequence of the loss of a single executive authority, have also caused issues for entrepreneurship. First, with regard to the increased rigidity of the Beneficial rights, one outcome is that mana as a means of rewarding those with ability has been side-lined by whakapapa. As this birder noted, authority does not connect to ability:

… those decisions are made – within our family – regardless of how knowledgeable you are, is by the lead person in the family. [#10-Beneficial]

The consequences of this rigidification have manifested in the operations of the committees, which, as some birders noted, were no longer guided by mana:

… I do believe that at times, sometimes our committees have been very biased; they haven’t been fair. Whether that’s for their own self-greed, for their own self-interest, I don’t think they’re withholding their part of being on that committee to respect our elders… I think people can have self-interest and I don’t think at times people are fair. [#7-Beneficial]

… in the old days… there was a group of elders who represented some of the… families who were deeply entrenched in birding. Some of those people had more mana than the others. Back in the day their word was respected as being the law. So once they made a decision it was pretty much adhered to by everybody… the modern committee system it can get a bit lop-sided when you’ve got too many family members from one family they can sort of manipulate the outcomes of things a little bit towards favouring themselves. [#11-Beneficial]

Voting, when tied to the rigid blood right system, may have discouraged meritocratic behaviours, thus seeing kinship trumping ability. To be clear, we are not suggesting that the whakapapa-rights system should change, but rather that an executive authority could reward ability by providing a way to gain mana through various roles in the executive, from leadership to education, with possible benefits given to those who had provided these services.

Even more problematic is the increased fluidity of rights that has occurred, causing some whānau to have not birded in generations. This has seen the ability to bird reduced in a way that negatively impacts natural capital. As this birder explained:

… my father sort of said at one stage that probably the biggest risk for our way of life as muttonbirders is new people that haven’t been down there before because they bring a different sort of viewpoint to it and probably a different tikanga and they may have views that are not so much steeped in tradition and knowledge… it’s important for people to build up knowledge and retain it and pass it on to the next generation as to how to best manage each area… Muttonbirding is something that has been passed down… to people who treasure it and respect it and you look after it… I think that’s probably the best way to manage the resource as such is to have people who know what they are doing rather than new people who are trying to sort of start out… [#11-Beneficial]

The executive authority would be able to reduce some of the negative impacts on natural capital by ensuring that new birders have the necessary ability through its communication and education functions.

Finally, the loss of clearly defined territory, resulting in ‘open’ manu, has the potential to decrease natural capital, as it can result in a loss of ability. As this birder outlined:

… there’s some open manu [islands]… Then there’s others that are where you have your whānau manu… The family ones, in my opinion, it’s the best model because as far as your responsibilities and particularly what you do impacts you directly and you’re responsible for whatever happens… [to] the manu. [#10-Beneficial]

Providing clarity regarding the geophysical configurations of rights would be an important role for the executive authority, which would help enhance the opportunity to bird by connecting sustainability responsibility to a specific area.

CONCLUSION

The re-establishment of executive authority on the Tītī Islands would likely generate more opportunity for whānau entrepreneurs to apply their ability and increase their financial, socio-human and natural capital through innovation. However, this would not be easy, particularly because of the desire among birders to retain operational authority and perceptions that this could be threatened by any new, enhanced power, as the statements against the Ngāi Tahu tribal council attest. An executive authority could be constituted in such a way as to ensure operational authority was protected. Furthermore, judging by the increasing costs and approaching inability to recoup these from the market without further innovation, as well as questions of ongoing sustainability of the harvest, it is argued that if birders want to continue to harvest into the future, they cannot avoid some form of executive authority. Possible novel approaches to increasing financial, socio-human and natural capital were clear, from developing new products and marketing methods to hybrid cooperative structures and sustainability initiatives that blend Māori and western approaches, but none seem likely to be initiated without an executive authority.

While many of the birders interviewed noted they no longer harvested to increase financial capital but rather kept going to increase socio-human capital, as the tītī economy encapsulates so well, all three forms of capital are intrinsically linked. As this birder told us, muttonbirding needs to be financially viable if birders are to remain ahikā:

generally speaking the people who are best set up as far as their infrastructure and what not are the people who have continuity and get the next generation involved. In some respects, if you’re not really moving forward along the industrial business sort of models – its harder and harder to maintain presence on the island.[#11-Beneficial]

In other words, the birders who increase financial capital through enhanced ability and innovation, those who are ‘moving forward’, are those who will not only profit but are able to increase their socio-human capital. In turn, increased socio-human capital through ahikā increases natural capital as it enables people to enhance their ability to bird sustainably, as can be seen in this birder’s statement:

… if you haven’t actually worked birds there’s a big danger of not being able to do them properly. Often happens with new birders that are inexperienced they go and catch far too many and end up having to throw some out as they can’t work them. [#11-Beneficial]

Finally, socio-human capital is also an important means of increasing financial capital. As this birder notes, she was taught the tikanga around bird preparation and that ability enables her to sell the product at a premium, increasing the financial capital:

With us the emphasis was on quality not quantity so our muttonbirds were always pre-salted and that’s the way I was brought up, we would have to clean them, shave them with a sharp knife, shave the hairs off them, clean with a rag, rub them all down. They were really good muttonbirds… get a quality product and you will always be able to sell it and get a good price for it. [#16-Crown]

As this birder sums up perfectly, the three forms of capital are all interrelated, they cannot be considered independently:

… the cost of coming down, if you chose to recuperate your costs, that brings in a whole new ball game. You would like to be able to recuperate your costs so that you can continue the tradition not make money instead of having a job on the mainland it is now become the other way around that you are there to continue your tradition…in our household it is a holiday continuing tradition, protecting the land, maintaining the land all that goes in with protecting. [#17-Beneficial]

Operating in the ‘micro-opportunities’ that each right represents, the relationship between the three forms of capital are far clearer. Reports from various birders reinforce the risks of the current institutional framework to the ongoing viability of birding, not just with regard to financial capital but also socio-human and natural capitals, as an inability to go birding would undermine an activity that has been a bastion of Ngāi Tahu culture, and with falling returns a ‘race-to-the-bottom’ market has ensued, leading some birders to harvest in a less than sustainable manner. For individual indigenous entrepreneurs, the focus needs to be on enhancing ability so they can maintain balance between the three capitals, while the surrounding institutions need to help with this ability building and innovation whilst ensuring the opportunity to bird remains.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the birding families for providing their valuable insights. Funding (Ref No.16RF05) for this research was provided by Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, New Zealand’s Māori Centre of Research Excellence, and Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu.