Introduction

Statistics have shown that employee disengagement costs US organizations $550 billion annually (Clack, Reference Clack and Dhiman2020) while employee burnout costs organizations $300 billion annually globally (Bretland & Thorsteinsson, Reference Bretland and Thorsteinsson2015). This signifies a serious concern for organizations in addressing productivity loss. The job demands–resources (JD-R) theory (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004) has been widely researched in the past two decades in relation to work engagement and burnout. It shows two distinctive pathways where the motivational pathway shows the presence of job resources lead to higher work engagement while the health-erosion pathway shows the presence of job demands lead to higher burnout.

While the theory has been shown to reflect important aspects that drive employee job performance, recent studies have begun to expand the theory and search for antecedents that promote or hinder job demands and job resources. In particular, leadership is highly related to employee behaviour and work outcomes (Lee & Ding, Reference Lee and Ding2020). While many neo-charismatic theories (e.g., transformational, charismatic and transactional leadership) and newer leadership styles have been investigated, they are mostly investigated in Western countries (Kelloway, Turner, Barling, & Loughlin, Reference Kelloway, Turner, Barling and Loughlin2012). The studies conducted on leadership within the Asian context (Sim, Lee, Kwan, & Tuckey, Reference Sim, Lee, Kwan, Tuckey, D'Cruz, Noronha and Mendonca2021) raise a few issues.

Firstly, the organizational dynamics within Asian work contexts are relationship-focused with a strong emphasis on adherence to authority (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2011). Work values across cultures have been widely used to explain differences in work attitudes and outcomes between Asian and Western cultures (e.g., Noordin & Jusoff, Reference Noordin and Jusoff2010; Schermerhorn & Bond, Reference Schermerhorn and Bond1997). Whereas Westerners tend to be more individualist, Asian culture tends to be more group-oriented (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2011). One meta-analysis on leadership studies reported that at least 294 of 1,050 published studies (across 10 top-tier journals from 2000 to 2012) studied neo-charismatic theories, while only 32 were conducted on cross-cultural leadership approaches such as paternalistic leadership (Dinh, Lord, Gardner, Meuser, Liden, & Hu, Reference Dinh, Lord, Gardner, Meuser, Liden and Hu2014). This signifies the lack of studies conducted within the Asian context.

Secondly, the JD-R theory with the inclusion of leadership mostly only investigated western leadership styles such as authentic leadership (Adil & Kamal, Reference Adil and Kamal2020) and servant leadership (Kaltiainen & Hakanen, Reference Kaltiainen and Hakanen2022). As the JD-R theory literature has no studies relating to paternalistic leadership, our understanding of the JD-R theory is limited and remains a ‘black hole’ as far as leadership in the Asian context is concerned, even though Asians constitute 60% of the world's population (Ramachandran, Snehalatha, Shetty, & Nanditha, Reference Ramachandran, Snehalatha, Shetty and Nanditha2012). Therefore, more studies are needed on Asian leadership styles, such as paternalistic leadership, within the JD-R theory.

Underpinning the JD-R theory as the foundation of this study, the current study investigated the role of job demands and job resources in mediating the relationships between paternalistic leadership and work engagement and burnout. The study investigated influence at work and work meaningfulness as critical job resources in driving human capital development amid the rapid transformation of technology. Emotional and cognitive demands were investigated as job demands as they are reflective of the current industrial revolution of industry that is demanding high emotional and cognitive workloads. The findings of the current study aim not only to expand the existing literature on paternalistic leadership within the JD-R theory but also to extend the currently understudied understanding within the Asian context.

This study makes a threefold contribution to the current literature. The findings provide a stepping stone to future studies on the JD-R theory especially on Asian leadership within Asian countries. Paternalistic leadership, which originated from Taiwan, is seen to share the same belief in values in the leader–employee relationship. Hence, the current study firstly confirmed the applicability of the role of paternalistic leadership in other Eastern countries such as Malaysia (Erben & Guneser, Reference Erben and Guneser2008). Secondly, following the specific pathways within the JD-R theory, the study expanded on aspects of paternalistic leadership based on its push (i.e., authoritarian) and pull (i.e., benevolent and moral) elements. This provides further guidance for human resource practitioners on how to manage this leadership style. Finally, by including the human aspects of the JD-R theory, the study offers additional insights for situations in which employees and leaders are close, yet distant, in the dynamics of their relationships. The mediational analyses allow us to understand the mechanism behind these processes. This enhances our understanding of the behaviour and function of workplaces in Asian countries (Noordin & Jusoff, Reference Noordin and Jusoff2010).

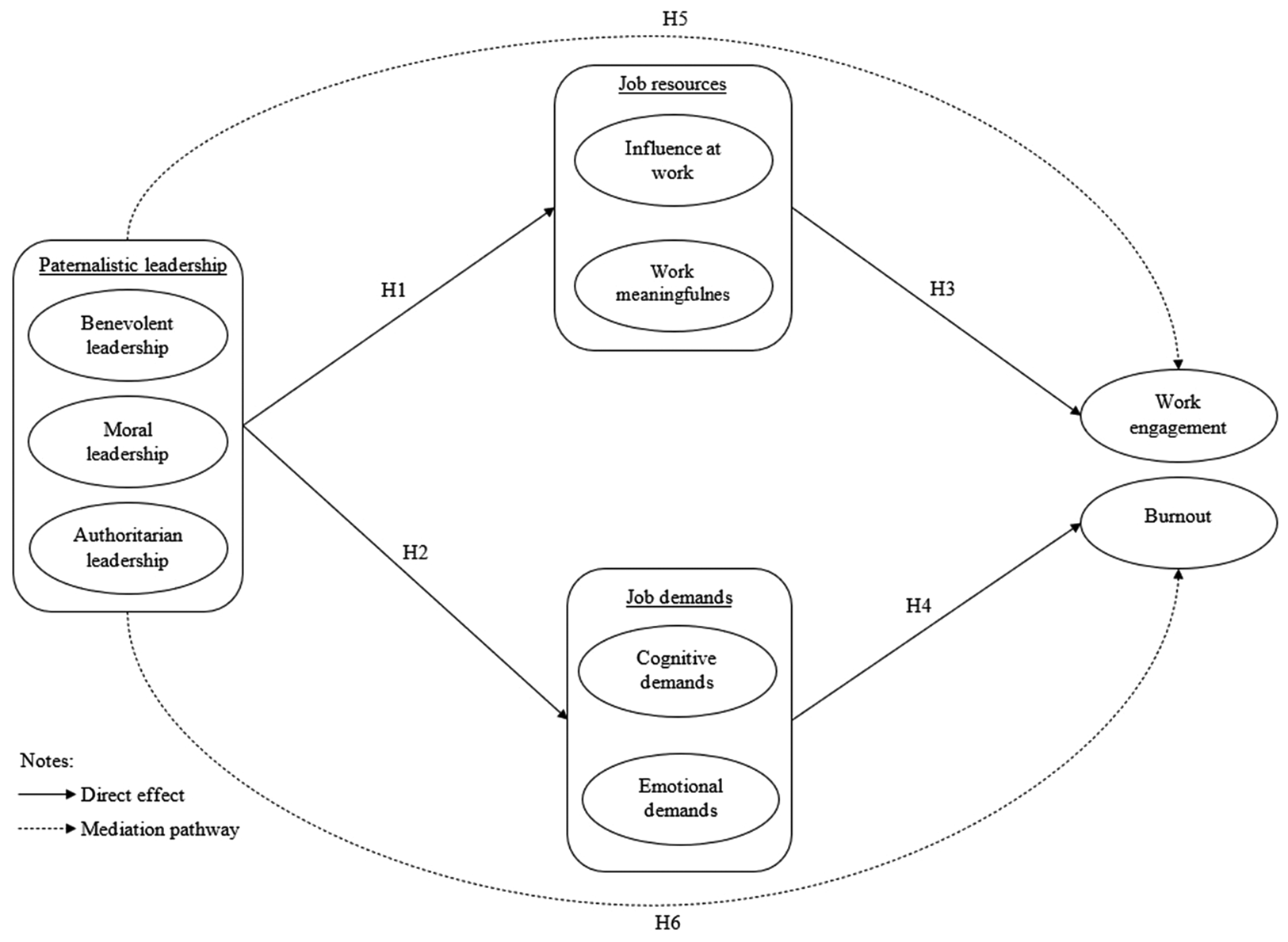

In this paper, we first introduce the concept of paternalistic leadership in relation to the JD-R theory. The development of the research hypotheses and conceptual framework are then discussed, as well as the quantitative research method design. Next, we report the results from the hypotheses testing. In the following section, the study's findings, its strengths, limitations and future research direction are discussed. Finally, we elaborate the study's theoretical and practical implications and draw the study's conclusion. Our proposed model is presented in Figure 1 below.

Figure. 1. Proposed model.

Review of the literature and hypotheses development

Paternalistic leadership, job demands and job resources

Paternalistic leadership is defined as ‘a style that combines strong discipline and authority with fatherly benevolence and moral integrity couched in a personalistic atmosphere’ (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000: 84). It comprises three aspects: authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership and moral leadership. Authoritarian leadership refers to the leadership behaviour of asserting a strong sense of authority and control over subordinates and demanding absolute obedience from them. On the other hand, benevolence refers to the leadership qualities that demonstrate individualized, holistic concern for subordinates' personal and familial well-being, similar to that shown by a father-like figure. Meanwhile, moral leadership refers to a leader who acts in a way that demonstrates a superior moral character and integrity through unselfish acts and leading by example (Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh, & Cheng, Reference Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh and Cheng2014; Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang, & Farh, Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004). It is a unique leadership style where it shares similarities with transformational and participative leadership across cultures, and authoritarian and nurturant-task leadership in hierarchical and collectivistic cultures (Aycan, Schyns, Sun, Felfe, & Saher, Reference Aycan, Schyns, Sun, Felfe and Saher2013), encompassing both human-centred and transactional leadership (Leclerc, Kennedy, & Campis, Reference Leclerc, Kennedy and Campis2021).

It has been suggested that benevolent leadership tends to create a conducive or psychologically safe environment by providing more influence or choice for employees to master their craft at the workplace which, in turn, promotes positive work outcomes (Wang & Cheng, Reference Wang and Cheng2010). In contrast, the authoritarian aspect of paternalistic leadership, which involves control over and obedience from followers, does not empower employees (i.e., does not provide them with opportunities to present their solutions or with the freedom to perform a task using their own method) (Chan, Huang, Snape, & Lam, Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh and Cheng2014). Finally, moral leadership focuses on the values that leaders follow and promote, and to which they adhere (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000). Paternalistic leadership has been defined as a leadership style that combines both strong discipline and authority, while incorporating fatherly-like behaviour that provides care towards employees' personal lives and caters to their needs (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh and Cheng2014; Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004), as well as becoming the role model for justice in an organization (Erben & Guneser, Reference Erben and Guneser2008).

Benevolent leadership has been found to lead to a higher level of influence at work among employees (Wang & Cheng, Reference Wang and Cheng2010). Employees' influence at work is derived from the empowerment given by leaders (e.g., encouraging employees to facilitate self-leadership and to participate in goal setting or strategies, and through providing a self-reward system) (Chan, Reference Chan2017). Through providing employees with influence at work, the criterion of having a sense of autonomy is fulfilled. This may increase their intrinsic motivation and is aligned to self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2000), particularly the autonomy component. In addition, benevolent leadership displays virtue and compassion towards employees, thus creating higher work meaningfulness among them (Karakas & Sarigollu, Reference Karakas and Sarigollu2013)

Extensive research has been conducted on the effects of paternalistic leadership on employees' burnout (e.g., Çetin, Toylan, Çakırel, & Çakırel, Reference Çetin, Toylan, Çakırel and Çakırel2017; Hiller, Sin, Ponnapalli, & Ozgen, Reference Hiller, Sin, Ponnapalli and Ozgen2019), but a lack of research is evident on how aspects or mechanisms of leadership lead to significant outcomes, and what and which aspects or mechanisms do so. We argue that paternalistic leadership is viewed as being inflexible, controlling and unwilling to experiment with innovative ideas or to share information on work-related matters (Gu, Wang, Liu, Song, & He, Reference Gu, Wang, Liu, Song and He2018; Siddique & Siddique, Reference Siddique and Siddique2019). This leads to employees lacking a sense of identification with the organization as their contribution is not valued by the organization's leaders.

The authoritarian aspect of paternalistic leadership often relates to the characteristic of a state of authority which enforces strict routines and demands on employees (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013). These leaders' demands frequently cannot be disputed (Schermerhorn & Bond, Reference Schermerhorn and Bond1997). By fulfilling leaders' directions and obligations, costly mistakes are thus avoided with such mistakes less tolerated in this type of collectivistic culture (Blunt, Reference Blunt1988; Lim, Reference Lim2016). It is evident that unconditional obedience towards authority is expected from employees (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004). This becomes cognitively taxing to employees as they seek to deliver good work, while incurring high emotional costs to cope with these demands. Employees under this type of leadership experience an array of negative emotions at work (e.g., frustration or desperation in seeking to fulfil leaders' demands). Consequently, employees become emotionally challenged in sustaining job demands which require a high level of effort (Laila & Hanif, Reference Laila and Hanif2017). In essence, both cognitive and emotional demands are often exerted by leaders, requiring physiological or psychological effort from employees to sustain and maintain leaders' expectations.

It has been suggested that moral leadership increases employees' positive attitudes as they are provided with job resources such as job autonomy (Dhar, Reference Dhar2016) or work meaningfulness (Wang & Xu, Reference Wang and Xu2019). Both the benevolence and morality aspects of paternalistic leadership have been known to mitigate the effects of leaders' authoritarian behaviour. Leaders' benevolence tends to foster in-group identity by providing personal care, with the leader acting as a fatherly-like figure (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013), while moral leadership qualities demonstrate superior personal values which do not abuse authority for personal gain, and exemplify a person with decent personal and work conduct (Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000).

These three aspects of paternalistic leadership (i.e., authoritarian leadership, benevolent leadership and moral leadership) mostly focus on a direction that is positive or negative. Based on past research, as paternalistic leadership aspects are comprised of contradictory roles, it is not considered a unified construct, being characterized by authoritarianism and its opposite on the continuum, benevolence, as well as morality (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013). However, these aspects may occur at the same time (Erben & Guneser, Reference Erben and Guneser2008). A brief search on Google Scholar on paternalistic leadership from 2004 to the current time shows it has been investigated 57 times, 40 of which were investigated through its sub-components. Some researchers have argued that looking at paternalistic leadership through its sub-components may invite a paradoxical view on this leadership style (Pellegrini & Scandura, Reference Pellegrini and Scandura2008), with strong support for the view that paternalistic leadership may display both push (i.e., authoritarian) and pull (i.e., benevolent and moral) elements (Cheng, Huang, & Chou, Reference Cheng, Huang and Chou2002). Thus, these sub-components of paternalistic leadership warrant an investigation within the JD-R theory.

In addition, we argue that within the spectrum of JD-R theory (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017), benevolent and moral leadership are associated with the motivational pathway while authoritarian leadership is associated with the health erosion pathway. Therefore, the contrasting role of paternalistic leadership may produce a mixed result on how employees' job resources and demands are provided by each aspect of paternalistic leadership. Hence,

Hypothesis 1: Benevolent and moral leadership (but not authoritarian leadership) are positively related to job resources.

Hypothesis 2: Authoritarian leadership (but not benevolent and moral leadership) is positively related to job demands.

Job demands, job resources, work engagement and burnout

The JD-R theory (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004) provides a heuristic way for viewing how job characteristics influence the employee's work engagement and burnout and, subsequently, his/her job performance. Two pathways are specifically highlighted: the motivational pathway and the health erosion pathway. The motivational pathway proposes that the presence of job resources will increase the employee's work engagement, while the health erosion pathway proposes that the presence of job demands will increase his/her likelihood of burnout.

Job resources have been referred to as ‘those physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that either/or (1) reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs; (2) are functional in achieving work goals; (3) stimulate personal growth, learning and development’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004: 296).

It is suggested that job resources increase work engagement which has been described as ‘a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004: 295). When job resources are plentiful, in today's work life, the focus is on the needs of individuals, with employees placing the emphasis on how much influence they have at work and whether their work is meaningful.

While influence at work refers to the amount of control employees have at their work without being micro managed (Karasek, Reference Karasek1979), work meaningfulness is defined as the ‘value of a work goal or purpose, judged in relation to an individual's own ideals or standards’ (May, Gilson, & Harter, Reference May, Gilson and Harter2004). Both influence at work and work meaningfulness are important and function hand in hand, with work meaningfulness often existing when employees have control over their work tasks, which leads to higher empowerment in their daily tasks (Lee, Idris, & Delfabbro, Reference Lee, Idris and Delfabbro2017). Generally, labour which requires thought poses cognitive demands on employees who are valued as humans capable of innovative and creative solutions, with decision-making skills that cannot be replaced by technologies (Ghislieri, Molino, & Cortese, Reference Ghislieri, Molino and Cortese2018).

Similarly, work meaningfulness has been found to be a compelling factor for employees to have higher organizational commitment and to be motivated to perform at work (Chalofsky & Krishna, Reference Chalofsky and Krishna2009; Steger, Dik, & Duffy, Reference Steger, Dik and Duffy2012). In essence, influence at work often relates directly to the motivational pathway, while work meaningfulness promotes work values that are indirectly linked to higher motivation at work. Evidently, both of these job resources (i.e., influence at work and work meaningfulness) may contribute to the positive gains of work engagement of an individual through the motivational pathway (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2008). Studies in many countries, both Western and Eastern, have shown that job resources in the aspects of control at work and work meaningfulness increase work engagement (Roslan, Ho, Ng, & Sambasivan, Reference Roslan, Ho, Ng and Sambasivan2015; Tuckey, Bakker, & Dollard, Reference Tuckey, Bakker and Dollard2012). Thus, job resources providing autonomy and meaning as motivating factors at work have become critical in driving human capital development in the midst of the rapid transformation of technology.

The other pathway within the JD-R theory is the health erosion pathway where the presence of job demands is defined as ‘those physical, psychological, social or organizational aspects of the job that require sustained physical and/or psychological (i.e., cognitive or emotional) effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004: 296). Job demands have been stated to increase burnout which has been defined as a state of mental weariness (Schaufeli & Bakker, Reference Schaufeli and Bakker2004). In the workplace revolution in which service jobs are overtaking industrial jobs, with ‘new tasks in which manual labour is replaced by thoughtful labour’ (Shulman & Olex, Reference Shulman and Olex1985: 98), the need to engage cognitively and emotionally with work tasks has become an important demand on which to focus.

Cognitive demands relate to job tasks that are meticulous in nature which require employees to focus on details and which are often multifaceted and difficult to perform. Emotional demands relate to emotionally draining job tasks which require the involvement of emotions due to constant interactions with recipients such as clients or colleagues in the completion of tasks (Heuven, Bakker, Schaufeli, & Huisman, Reference Heuven, Bakker, Schaufeli and Huisman2006). While job demands may not always be negative (Bakker & Demerouti, Reference Bakker and Demerouti2017), meeting those demands may require high effort over time resulting in physiological or psychological costs such as emotional exhaustion or burnout (Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner, & Schaufeli, Reference Demerouti, Bakker, Nachreiner and Schaufeli2001).

Several studies have shown that high job demands lead to a high level of burnout. Cognitive demands were found to relate to mental exhaustion (Huyghebaert, Gillet, Lahiani, & Fouquereau, Reference Huyghebaert, Gillet, Lahiani and Fouquereau2016), while mentally exacting and complex work tasks often predict burnout in employees (de Jonge & Dormann, Reference de Jonge and Dormann2006). Similar findings were also reported in Asian countries, with one recent study on Malaysian employees finding that specific emotional demands and physical demands lead to work-related burnout (Muhamad Nasharudin, Idris, & Young, Reference Muhamad Nasharudin, Idris and Young2020). These findings all displayed the health erosion pathway as predicted by the JD-R theory. Generally, the higher psychological effort required to sustain the leader's demands often promotes negative emotions such as stress or anxiousness (Laila & Hanif, Reference Laila and Hanif2017). In fact, this perceived negative array of emotions, and the inability to manage them, has been shown to be the key factor to burnout (Schaufeli, Taris, & Van Rhenen, Reference Schaufeli, Taris and Van Rhenen2008). Therefore, we propose that job resources and job demands will have a direct and positive impact on work engagement and burnout, as formulated in the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Job resources are positively related to work engagement.

Hypothesis 4: Job demands are positively related to burnout.

Job resources as a mediator between paternalistic leadership and work engagement

Leadership has been considered as one of the important antecedents in influencing employees' work processes through job resources and job demands. In the current context, paternalistic leadership, consisting of consideration, care and integrity (i.e., benevolent and moral aspects of paternalistic leadership but not the authoritarian aspect), has been known to provide job resources to employees such as promoting employees' influence at work (Dhar, Reference Dhar2016; Wang & Cheng, Reference Wang and Cheng2010) and work meaningfulness (Karakas & Sarigollu, Reference Karakas and Sarigollu2013; Wang & Xu, Reference Wang and Xu2019), thus predicting a higher level of employees' work engagement (Cenkci & Özçelik, Reference Cenkci and Özçelik2015; Öge, Çetin, & Top, Reference Öge, Çetin and Top2018). In the current study, we explain how paternalistic leadership serves as an antecedent to the provision of job resources and job demands within the JD-R theory, hence activating both the motivational and health erosion pathways.

We argue that the benevolent aspect of paternalistic leaders is useful in activating the motivational pathway. Higher work engagement by employees can result from paternalistic leaders who provide them with a decent amount of care and support (Cenkci & Özçelik, Reference Cenkci and Özçelik2015; Öge, Çetin, & Top, Reference Öge, Çetin and Top2018). This supports the above notion that when psychological needs for influence at work and finding work meaningful are supported by leaders, employees often respond favourably by exhibiting higher levels of work engagement even within the confines of a culture of obedience and adherence to instruction (Shu, Reference Shu2015). This is further supported under the influence of benevolent leaders through which employees are found to increase their compliance and work motivation towards their leaders' demands. Therefore, the effects of benevolent and moral leaders (but not authoritarian leaders) on work engagement may be observed via the motivational pathway through job resources (i.e., influence at work and work meaningfulness).

In relation to authoritarian leadership, we argue that it would have a negative relationship with the motivational pathway. A high level of respect for authority is found especially in a culture of high collectivism which is high in power distance. In other words, employees are expected to show unreserved loyalty and compliance towards their leader (Rockstuhl, Dulebohn, Ang, & Shore, Reference Rockstuhl, Dulebohn, Ang and Shore2012). In a ‘no questioning’ context, authoritarian leadership will have negative relationships with lower levels of job resources and work engagement (Cenkci & Özçelik, Reference Cenkci and Özçelik2015; Shu, Reference Shu2015).

Overall, it has been suggested that paternalistic leadership tends to provide a holistic concern for employees, but at the expense of their liberty (Erben & Guneser, Reference Erben and Guneser2008). As explained above, aspects of paternalistic leadership function differently in the motivational pathway. Hence,

Hypothesis 5: Job resources mediate the relationship between paternalistic leadership and work engagement.

Job demands as a mediator between paternalistic leadership and burnout

Similarly, looking at the health erosion pathway, benevolent leadership endorses a genuine and caring nature towards employees and often acts as a fatherly-like figure, with this expected to develop a sense of respect, gratitude, indebtedness and liking (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013). Consequently, positive emotions or reactions arising from the benevolent aspect of paternalistic leadership are found to be effective in promoting a lower level of job demands and better well-being (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Eberly, Chiang, Farh and Cheng2014; Farh & Cheng, Reference Farh, Cheng, Li, Tsui and Weldon2000). Similar reactive patterns can be found with moral leadership, with this type of leadership providing a sense of justice by ‘walking the talk’ of being a moral leader among employees.

As reported in a previous study about the distinctive characteristics of paternalistic leadership, authoritarian leaders tend to promote the use of rules, with their demands possibly resulting in higher cognitive and emotional costs from employees (Laila & Hanif, Reference Laila and Hanif2017). The negative state of affairs thus experienced by employees is characterized by anxiety or anger (Hiller et al., Reference Hiller, Sin, Ponnapalli and Ozgen2019). These negative emotions have been shown to have detrimental effects on employees' psychological well-being (Vecchio, Reference Vecchio2000). Researchers have stated that negative emotions, such as stress or anxiousness, are some of the compelling factors that cause an individual to experience burnout (Schaufeli, Taris, & Van Rhenen, Reference Schaufeli, Taris and Van Rhenen2008). Hence,

Hypothesis 6: Job demands mediate the relationship between paternalistic leadership and work engagement.

Method

Participants

The current study employed a cross-sectional design with 431 employees (median age [M age] = 31.58; standard deviation [SD] = 9.60) participating from 33 organizations within the service industry, with more female participants (N = 249, 57.8%) than male participants. All participants were executive-level white-collar employees with desk tasks who had at least a bachelor's degree, been working in the organization and under the current leader for at least 3 months. The mean length of employees' work in the organization was 4.49 years (SD = 5.96), while the mean length of employees' work under the same leader was 3.26 years (SD = 4.51). Employees worked 46.18 h per week (SD = 77.87), while employees' mean income was Malaysian ringgit (RM) 3500.18 (SD = 2086.97).

The study was approved by the ethics board of the researchers' university. Organizations were approached by email using a list of organizations identified in Malaysia's small and medium enterprise database. Meetings were scheduled with the human resources (HR) manager of the interested organization to provide further briefing on the purpose of the study. The researcher then emailed copies of the informed consent form, a letter from the university approving the study and a link to the survey questionnaire. The instructions on the informed consent form made clear that participants' participation was entirely voluntary, and that confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed. Each organization's HR manager then asked study participants to fill in the informed consent form and the online survey. Participants then returned the completed questionnaire to the HR manager in a sealed envelope, with the researchers and their research assistant returning to each organization to collect the completed questionnaires.

Instruments

Paternalistic leadership was measured using the 26 items from Cheng et al.'s (Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004) paternalistic leadership scale which measures benevolent aspects (11 items), moral aspects (six [6] items) and authoritarian aspects (nine [9] items) of this leadership style. The scale ranged from ‘1’ = strongly disagree to ‘6’ = strongly agree. An example of a benevolent leadership item is as follows: ‘My leader is like a family member when he/she gets along with us’. An example of a moral leadership item is as follows: ‘My leader never avenges a personal wrong in the name of public interest when he/she is offended’. An example of an authoritarian leadership item is as follows: ‘My leader asks me to obey his/her instructions completely’. In the previous study by these authors, they reported the reliability of the scale as follows: benevolent (α = .94), moral (α = .90) and authoritarian (α = .89) (Cheng et al., Reference Cheng, Chou, Wu, Huang and Farh2004). The current study reported the reliability and convergent validity as follows: benevolent (composite reliability [CR] = .93, average variance extracted [AVE] = .58), moral (CR = .83, AVE = .56) and authoritarian (CR = .84, AVE = .56).

Work engagement was measured using nine items from the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9) (Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, Reference Schaufeli, Bakker and Salanova2006). The scale assessed the three factors of work engagement comprising vigour, dedication and absorption. The scale was on a 7-point range (‘1’ = never; ‘7’ = every day). An example of the items is as follows: ‘At my work, I feel bursting with energy’. The current study established the reliability and convergent validity of the scale (CR = .93, AVE = .64).

Burnout was measured using a 3-item scale (Diefendorff, Greguras, & Fleenor, Reference Diefendorff, Greguras and Fleenor2016) rated on a 5-point range where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. An example of the items is as follows: ‘My job emotionally exhausts me’. Higher scores on this scale would indicate the higher level of burnout of an individual. The current study established the reliability and convergent validity of the scale (CR = .87, AVE = .69).

Influence at work was measured using four items from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ II) (Pejtersen, Kristensen, Borg, & Bjorner, Reference Pejtersen, Kristensen, Borg and Bjorner2010) which assesses various psychosocial work environment elements (e.g., demands at work, work organization and job contents, etc.). The influence scale, under the subscale of COPSOQ II (work organization and job contents), was used in the current study. The scale was measured on a 5-point range (‘1’ = never; ‘5’ = always). One example of the items is as follows: ‘Do you have a large degree of influence concerning your work?’ The current study established the reliability and convergent validity of the scale (CR = .85, AVE = .66).

Work meaningfulness was measured using three items from the COPSOQ II (Pejtersen et al., Reference Pejtersen, Kristensen, Borg and Bjorner2010). The work meaningfulness scale, under the subscale of COPSOQ II (work organization and job contents) was used in the current study. The scale assessed the work meaningfulness experienced by an individual. The scale was measured on a 5-point range (‘1’ = never; ‘5’ = always). One example of the items is as follows: ‘Is your work meaningful?’ The current study established the reliability and convergent validity of the scale (CR = .87, AVE = .69).

Cognitive demands were measured using four items from the COPSOQ II (Pejtersen et al., Reference Pejtersen, Kristensen, Borg and Bjorner2010). The cognitive demands scale, under the subscale of COPSOQ II (demands at work) was used in the current study. The scale assessed the cognitive demands of an individual at work. The scale was measured on a 5-point range, where ‘1’ = never, ‘5’ = always. An example of the items is as follows: ‘Does your work require you to make difficult decisions?’ The current study established the reliability and convergent validity of the scale (CR = .76, AVE = .61).

Emotional demands were measured using four items from the COPSOQ II (Pejtersen et al., Reference Pejtersen, Kristensen, Borg and Bjorner2010). The emotional demands scale, under the subscale of COPSOQ II (demands at work) was used in the current study. The scale assessed the emotional demands of an individual at work. The scale was measured on a 5-point range (‘1’ = never; ‘5’ = always). An example of the items is as follows: ‘Does your work put you in emotionally disturbing situations?’ The current study established the reliability and convergent validity of the scale (CR = .89, AVE = .67).

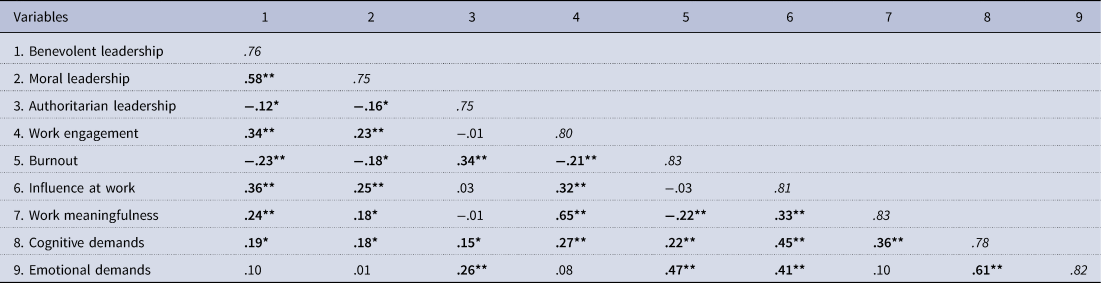

The numbers inside brackets represent the original number of items. Values italicized diagonally across the table indicate the square root of AVE of the variables, while correlations below the respective square root of AVE show good discriminant validity (Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins, & Kuppelwieser, Reference Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins and Kuppelwieser2014), as shown in this table: N (individual) = 431; *p < .05; and **p < .001.

Analysis strategy

The overall test results were analysed through structural equation modelling using IBM's AMOS 27.0. A two-step approach wherein a measurement model was first fitted in a confirmatory factor analysis, followed by the testing of hypotheses in a structural model. Missing data (.0067% of total responses) were replaced using expectation-maximization imputation. The testing of assumptions, such as normality, homoscedasticity, linearity and multicollinearity (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins and Kuppelwieser2014), was conducted prior to the overall analyses.

Results

Descriptive analysis, correlations between all variables and reliability of the measures of the current study are shown in Table 1. All assumptions were met except for multivariate normality (kurtosis = 335.23, critical ratio [c.r]. = 58.60), in which bias-corrected and accelerated (BCa) bootstrapping at a 95% confidence interval (CI), employing 2,000 bootstrap samples, was used as remedy (Byrne, Reference Byrne2016). Furthermore, six multivariate outliers were removed to improve model fit.

Table 1. Correlation matrix and square root of AVE of variables

Note: * p < .05; ** p < .001.

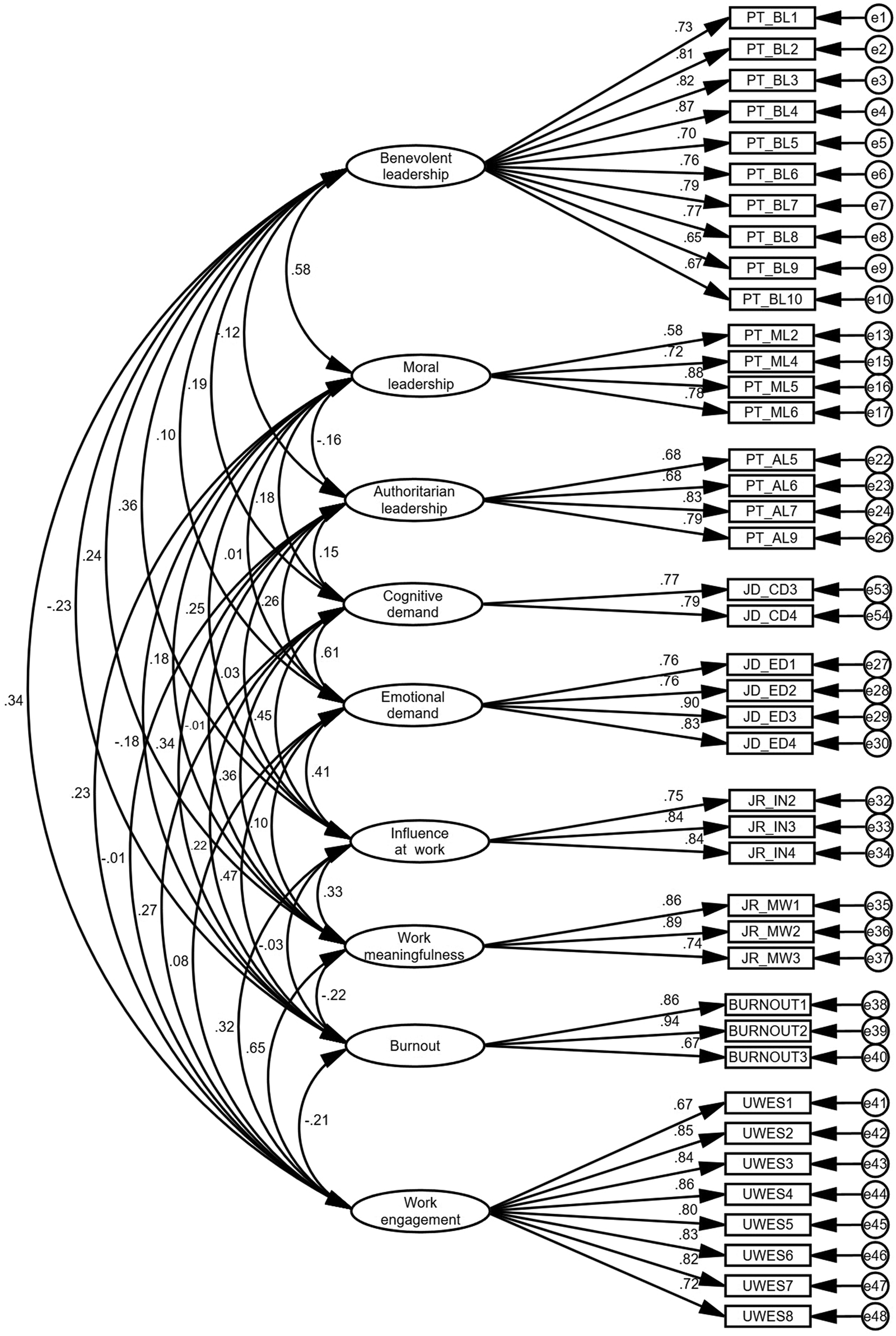

Measurement model

A measurement model, comprising the following variables: benevolent leadership, moral leadership, authoritarian leadership, work engagement, burnout, influence at work, work meaningfulness, cognitive demands and emotional demands, was assessed. We followed recommendation by Kline (Reference Kline2015) on testing the model fit. The model would show a good fit if its ratio of chi-square score (χ 2) to degrees of freedom (df) was less than 3; if it had a comparative fit index (CFI) score of .90 and above; and if its root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was less than .08; its standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was less than .08; and its p-value was less than .05 (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Sarstedt, Hopkins and Kuppelwieser2014; Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow, & King, Reference Schreiber, Nora, Stage, Barlow and King2006).

The initial model did not show a good fit (χ 2 = 3,652.90, df = 1,289, χ 2/df = 2.83, CFI = .83, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .07, p < .001). Therefore, to improve model fit, items with low loadings were removed one by one until a measurement model with an acceptable model fit was reached. Therefore, in total, 12 items were removed due to low factor loadings: one item from the benevolent leadership subscale; two items from the moral leadership subscale; five items from the authoritarian leadership subscale; one item from the work engagement scale; one item from the influence at work subscale; and two items from the cognitive demands subscale. The final model showed a good fit (χ 2 = 1,906.16, df = 743, χ 2/df = 2.57, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .06, p < .001). Figure 2 below represents the final measurement model.

Figure. 2. Final measurement model.

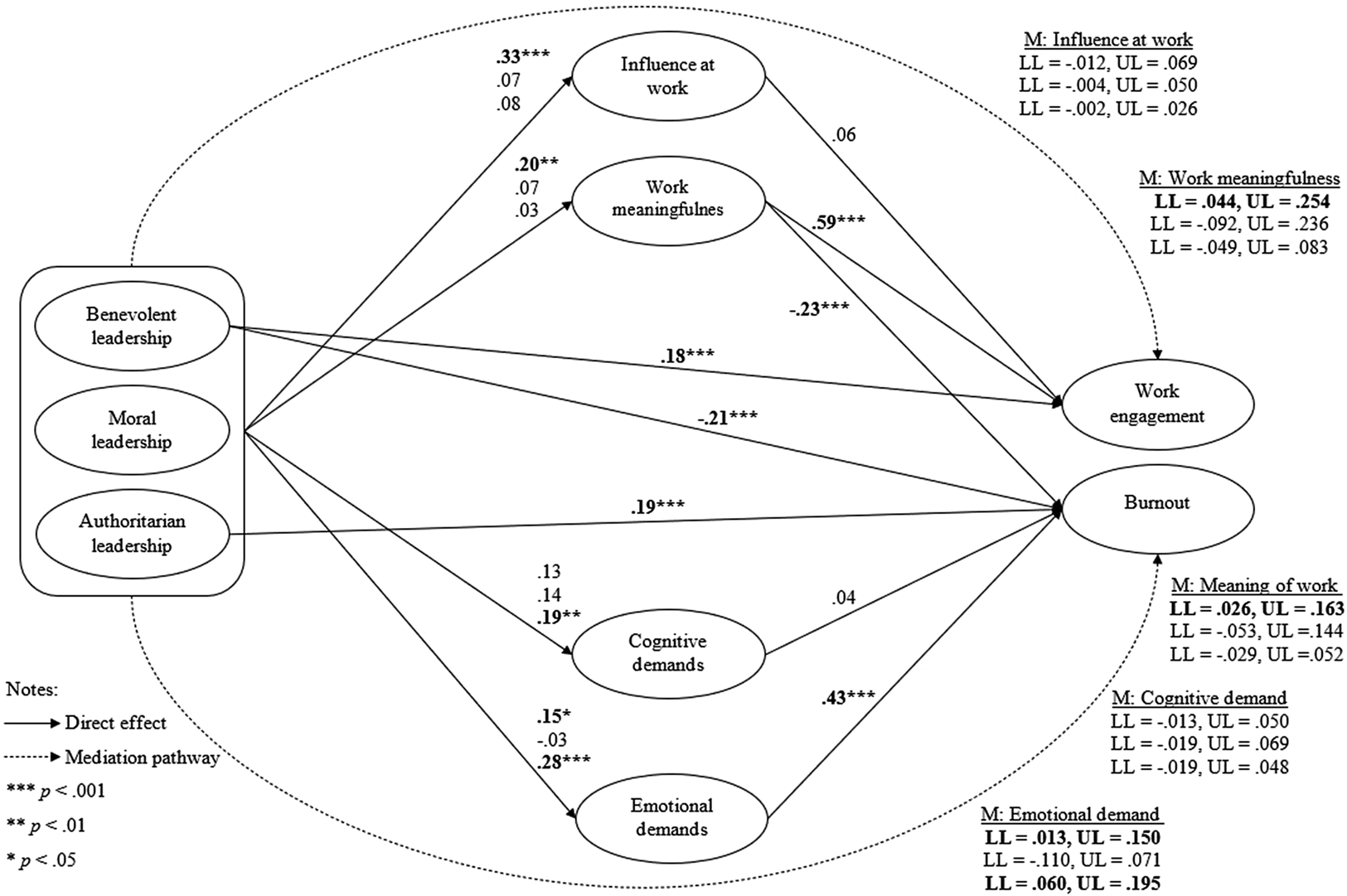

Structural model

The proposed structural model did not show a good fit (χ 2 = 1,996.27, df = 754, χ 2/df = 2.65, CFI = .89, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .08, p < .001). Thus, the model was re-specified through the addition of new regression paths by looking for the largest modification index (MI) and parameter change of regression weights between variables (Byrne, Reference Byrne2016). New regression paths were added to the model only if they make substantive theoretical sense (Gallagher, Ting, & Palmer, Reference Gallagher, Ting and Palmer2008). In total, four model re-specifications were made (i.e., benevolent leadership → work engagement; benevolent leadership → burnout; work meaningfulness → burnout; authoritarian leadership → burnout). The final re-specified model showed a good fit (χ 2 = 1,912.91, df = 750, χ 2/df = 2.55, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .06, p < .001).

Hypothesis 1 stated that benevolent and moral leadership (but not authoritarian leadership) are positively related to job resources. The study found that benevolent leadership was positively related to influence at work (β = .33, p < .001) and work meaningfulness (β = .20, p = 003). Moral leadership was not related to influence at work (β = .07, p = .342) nor to work meaningfulness (β = .07, p = .331). Authoritarian leadership was not related to influence at work (β = .08, p = .159) nor to work engagement (β = .03, p = .650). Hence, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 2 stated that authoritarian leadership (but not benevolent and moral leadership) is positively related to job demands. The study found that authoritarian leadership was positively related to cognitive demands (β = .19, p = 002) and emotional demands (β = .28, p < .001). Benevolent leadership was not related to cognitive demands (β = .13, p = .076) but was negatively related to emotional demands (β = .15, p = .021). Moral leadership was not related to cognitive demands (β = .14, p = .071) nor to emotional demands (β = −.03, p = .658). Hence, Hypothesis 2 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 3 stated that job resources are positively related to work engagement. The study found that work meaningfulness was positively related to work engagement (β = .59, p < 001), but influence at work was not related to work engagement (β = .06, p = .254). Hence, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 4 stated that job demands are positively related to burnout. The study found that emotional demands were positively related to burnout (β = .43, p < .001), but cognitive demands were not related to burnout (β = .04, p = .561). Hence, Hypothesis 4 was partially supported.

Mediation analyses

Mediation analyses were performed for Hypotheses 5 and 6 to test for the mediation effects of influence at work and work meaningfulness on the relationships between the three leadership types and work engagement (Hypothesis 5) as well as the mediation effects of cognitive demands and emotional demands on the relationships between the three leadership types and burnout (Hypothesis 6). The mediation effects of work meaningfulness on the relationships between the three leadership types and burnout were also tested. Indirect effects were estimated using a user-defined estimand called MyIndirectEffects for AMOS (Gaskin & Lim, Reference Gaskin and Lim2018). The estimand produces unstandardized indirect effect estimates, lower and upper bounds of the estimates (employing bias-corrected bootstrapping using 2,000 samples at 95% CI) and p values. The mediation effect is considered significant if zero (‘0’) was not present between the lower and upper bounds of the estimates.

Hypothesis 5 stated that job resources mediate the relationship between paternalistic leadership and work engagement. The results showed that influence at work was not a significant mediator of the relationship between benevolent leadership and work engagement (Beta [B] = .022, BCa 95% CI [−.012 to .069], p = .182); moral leadership and work engagement (B = .006, BCa 95% CI [−.004 to .050], p = .221); and authoritarian leadership and work engagement (B = .004, BCa 95% CI [−.002 to .026], p = .183). The results also showed that work meaningfulness was a significant mediator of the relationship between benevolent leadership and work engagement (B = .145, BCa 95% CI [.044–.254], p = .001). However, work meaningfulness was not a significant mediator of the relationship between moral leadership and work engagement (B = .068, BCa 95% CI [−.092 to .236], p = .389), nor of the relationship between authoritarian leadership and work engagement (B = .016, BCa 95% CI [−.049 to .083], p = .621). Hypothesis 5 was partially supported.

Hypothesis 6 stated that job demands mediate the relationship between paternalistic leadership and work engagement. Cognitive demands were not a significant mediator of the relationship between benevolent leadership and burnout (B = .006, BCa 95% CI [−.013 to .050], p = .399), moral leadership and burnout (B = .009, BCa 95% CI [−.019 to .069], p = .366) and authoritarian leadership and burnout (B = .008, BCa 95% CI [−.019 to .048], p = .443). Emotional demands were a significant mediator of the relationships between benevolent leadership and burnout (B = .073, BCa 95% CI [.013–.150], p = .018) and between authoritarian leadership and burnout (B = .117, BCa 95% CI [.060–.195], p = .001). Emotional demands were not a significant mediator of the relationship between moral leadership and burnout (B = −.020, BCa 95% CI [−.110 to .071], p = .653). Hypothesis 6 was partially supported. Figure 3 below represents the final model.

Figure. 3. Final model.

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate the Taiwan-derived paternalistic leadership and to identify its relevance within the Malaysian context. The study's findings establish the stance on the effectiveness of the sub-components of paternalistic leadership as a type of Asian leadership comprising multiple aspects. The findings also support the applicability of paternalistic leadership in the Malaysian context, a country which supports similar cultural values to those in Taiwan, such as a relationship-oriented culture with adherence to authority (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2011). Previous research linking leadership to the JD-R theory has focused mainly on Western styles of leadership, such as transformational and empowering leadership, that are usually linear in their leadership aspects (Katou, Koupkas, & Triantafillidou, Reference Katou, Koupkas and Triantafillidou2021; Lee, Idris, & Tuckey, Reference Lee, Idris and Tuckey2019). In addition, no studies have yet investigated the three aspects of paternalistic leadership within the JD-R theory.

Our study's contribution lies in investigating the contrasting push factors (i.e., the authoritarian aspect) and pull factors (i.e., benevolent and moral aspects) of paternalistic leadership (Chan et al., Reference Chan, Huang, Snape and Lam2013), a well-known Asian leadership style. This style of leadership is related to employees' job resources and job demands, mainly through the motivational and health erosion pathways. The push factor of authoritarian leadership has positive associations with both cognitive and emotional demands, and higher levels of burnout. The pull factor of benevolent leadership has positive associations with both influence at work and work meaningfulness, and higher work engagement. Moral leadership did not show any relationships within the JD-R theory.

Specifically, our study investigated: (1) how the benevolent and moral aspects of paternalistic leadership are positively related to influence at work and work meaningfulness as job resources, and to higher work engagement, activating the motivational pathway; and (2) how the authoritarian aspect of paternalistic leadership is positively related to cognitive and emotional demands as job demands in leading to a higher level of burnout, activating the health erosion pathway. Overall, the study found that benevolent leadership (but not authoritarian and moral leadership) was related to higher work engagement and lower burnout in employees through work meaningfulness (but not influence at work). In addition, the study found that emotional demands (but not cognitive demands) mediated the relationship between authoritarian leadership (but not benevolent and moral leadership) and burnout.

Our results provide support for how aspects of paternalistic leadership relate to both motivational and health erosion pathways within the JD-R theory. Benevolent leaders were found to be related to work engagement through work meaningfulness (but not influence at work), partially supported the hypothesis. This finding supports previous studies conducted in the Malaysian context where employees who perceived their work to be meaningful, such as having a positive perception of the person–job fit or having adequate supervisory and/or co-worker support, tended to be more enthusiastic and more engaged in their daily tasks (Ahmed, Majid, & Zin, Reference Ahmed, Majid and Zin2016; Chung & Angeline, Reference Chung and Angeline2010). Specifically, the perception of work meaningfulness was positively associated with benevolent leadership (Karakas & Sarigollu, Reference Karakas and Sarigollu2013). As in the findings of previous studies, work meaningfulness may create a higher intrinsic motivation (improving work engagement in general) when leaders provide employees with a purpose or the feeling of being appreciated by the organization (Morrison, Burke, & Greene, Reference Morrison, Burke and Greene2007; Steger, Dik, & Duffy, Reference Steger, Dik and Duffy2012). This is consistent with a study conducted in China by Chan and Mak (Reference Chan and Mak2012) which found that employees were able to find their work meaningful due to high-quality relationship with benevolent leaders.

The findings suggest that benevolent leadership relates to a conducive environment that resonates well with employees finding their own purpose, and the significance or importance of the work itself. When employees obtain a sense of meaning in their work, they take ownership and assume responsibility for the work they have done, with these values persisting to relate to a higher level of work engagement (Mayhew, Ashkanasy, Bramble, & Gardner, Reference Mayhew, Ashkanasy, Bramble and Gardner2007), while also developing the feelings of being appreciated by the organization (Morrison, Burke, & Greene, Reference Morrison, Burke and Greene2007; Steger, Dik, & Duffy, Reference Steger, Dik and Duffy2012).

On the other hand, the link between influence at work and work engagement was unclear in the current study, contradicting studies in the past (Sonnentag, Eck, Fritz, & Kühnel, Reference Sonnentag, Eck, Fritz and Kühnel2020; Vassos, Nankervis, Skerry, & Lante, Reference Vassos, Nankervis, Skerry and Lante2019). The reason for the lack of clarity could be the Malaysian work culture that is high in power distance. The unwillingness of employees to make their own decision without consulting a senior or leader (to avoid silly mistakes) (Blunt, Reference Blunt1988; Yousef, Reference Yousef2001) may be contradictory to leaders seeking to provide autonomy to employees and may buffer the effects of their leadership style. Thus, providing job autonomy in the Asian workplace may not be as beneficial in providing work meaningfulness to employees.

Although past studies on moral leadership have pull factors which overlap with benevolent leadership (Khorakian, Baregheh, Eslami, Yazdani, Maharati, & Jahangir, Reference Khorakian, Baregheh, Eslami, Yazdani, Maharati and Jahangir2021; Wang & Xu, Reference Wang and Xu2019), these findings were not supported within the JD-R theory, with the current study failing to show its relationship to the JD-R theory. The types of job resources and job demands were found to be not related to the morality aspect, which rejected all hypotheses related to moral leadership. Hence, it would be difficult to establish a relationship between the moral aspect of paternalistic leadership and job resources and job demands. We argue that moral leadership may be more related to issues such as honesty or integrity within an organization (Gini, Reference Gini1997).

On the other hand, the authoritarian aspect of paternalistic leadership was found to positively relate to burnout through emotional demands (but not cognitive demands), which partially supported the hypothesis. The results displayed the health erosion pathway formed between authoritarian leaders and burnout particularly through emotional demands. While previous studies suggested that Malaysian employees can work under the influence of authoritarian leaders (Erben & Guneser, Reference Erben and Guneser2008; Fikret-Pasa, Kabasakal, & Bodur, Reference Fikret-Pasa, Kabasakal and Bodur2001), the current study found that this is not without a cost: it comes with a price, that is, emotional demands.

We argue that this may be due to the collectivistic culture which prioritizes harmony among members of the in-group and the forgoing of personal agendas or well-being (Hofstede, Reference Hofstede2011). Individuals from a collectivistic culture are more inclined to conform to their in-group by suppressing their own ideas and thoughts: as a result, this demand on employees incurs a large amount of emotional costs (Laila & Hanif, Reference Laila and Hanif2017). Over time, a negative state of affairs is created, with burnout in employees predicted (Lim, Reference Lim2016). In coping with this situation, employees' own behaviour reinforces these emotional demands. For example, employees tend to act in accordance with the religious philosophy of redha and tawwakal in which they accept a situation as being predetermined without showing any negative emotions (Idris, Dollard, & Winefield, Reference Idris, Dollard and Winefield2010). In another study, employees were found to often manifest their anger in psychological stress-related conditions, such as anxiety or depression, rather than expressing it directly (Liu, Spector, & Shi, Reference Liu, Spector and Shi2007). Studies have found that employees under authoritarian leadership suppressed (negative) emotions more (Chiang, Chen, Liu, Akutsu, & Wang, Reference Chiang, Chen, Liu, Akutsu and Wang2021; Yao, Chen, & Wei, Reference Yao, Chen and Wei2022), a reflection of high emotional demands.

By integrating leadership within the JD-R theory, the current study has contributed to paternalistic leadership studies within the Malaysian context through its significant findings within this spectrum of leadership behaviours. As Malaysian culture values relationships or comradeship more than anything else (Blunt, Reference Blunt1988; Noordin & Jusoff, Reference Noordin and Jusoff2010), a benevolent leadership style is conducive as these leadership qualities demonstrate love and care. On the flipside, authoritarian leadership commands obedience and respect towards authority: within a culture that is high in power distance (Yousef, Reference Yousef2001), authoritarian leadership exudes communication barriers between employees and leaders. Overall, the study showed similar findings with past studies from other countries.

Strengths, limitations and future research directions

The current study is the first to investigate the contrasting aspects of paternalistic leadership. Each aspect has shown a very distinctive relationship within the JD-R theory, specifically, the positive aspects that benevolent leadership delivers, the negative aspects that authoritarian leadership delivers and the non-related relationship within the JD-R theory shown by moral leadership. As previous studies have only shown support for how paternalistic leadership may display both push and pull factors (Cheng, Huang, & Chou, Reference Cheng, Huang and Chou2002), the current findings highlight how paternalistic leadership relates to employees' job resources and job demands.

The few limitations from this study need to be addressed. Firstly, a cross-sectional design was used, with it widely acknowledged that cross-sectional design limits the ability of researchers to draw conclusions about the causality between variables (Lewig & Dollard, Reference Lewig and Dollard2003). Even though various models of mediation analysis (guided by numerous hypotheses) have been created in this study, the causal connections between the variables cannot be assumed. One way to examine these relationships is to conduct a longitudinal research design. In fact, using a longitudinal approach allows researchers to get around the issues of common method variance (see Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Thus, it is recommended that future studies employ a longitudinal research design to understand the temporal process of leadership's influence in the provision of job resources and job demands.

Furthermore, the current study has not explored the interactions between the sub-components of paternalistic leadership. Generally, the effectiveness of authoritarian leaders, in comparison to that of benevolent leaders and moral leaders, can be seen as oppositional. However, the interactions between multiple leadership styles may warrant further interest and investigation as the researcher may reach an understanding of the underlying mechanisms of the multiple aspects of leadership styles. Thus, future studies may take into consideration the interactions between the sub-components of paternalistic leadership.

Practical implications

From the current study's findings, the following practical implication focuses on the contribution of leaders to employee development. The reason is that leadership development remains a massive area into which organizations would like to tap. Most organizations are particularly interested in what leadership behaviours should be adopted in the organization and how (Dinh et al., Reference Dinh, Lord, Gardner, Meuser, Liden and Hu2014).

Organizations may want to promote and focus more on benevolent leadership which is helpful in projecting upon employees a more positive attitude towards their own work (Chan, Reference Chan2017). Talent practitioners may want to shape a culture of ‘treating your followers the way you treat your family’ and emphasizing the leader's kindness aspect. Generally, leaders may act as a counsellor for employees who can look up to or consult with their leaders on their personal well-being. This will lead to more positive work attitudes (i.e., increase in work engagement) and better well-being (i.e., decrease in burnout) for employees.

In addressing the positive relationships of authoritarian leadership, organizations may want to have one-to-one consultations or deliver inclusive leadership training on how leaders can exercise their leadership power or position in a more constructive manner within the organization or team. While we understand that enforcing strict rules and exercising one's authoritative status are ingrained within the Asian culture, it is important to highlight that leaders need to be aware of their behaviours that may be detrimental to employees' well-being.

These may ensure that employees' well-being is addressed. It may also avoid the downward spiral cost to organizations of higher employee turnover intention and the higher cost of retaining, retraining and hiring talented employees (Gupta & Shaheen, Reference Gupta and Shaheen2017). Hence, organizations may focus on the positive relationships of benevolent leadership within paternalistic leadership and less on authoritarian leadership.

Conclusion

The current study's findings particularly support the importance of the benevolent leadership aspect within paternalistic leadership, with this associated with higher influence at work and work engagement, as well as lower burnout, and the associated mediation pathways. Authoritarian leadership, however, is associated with higher emotional demands and burnout, and its associated mediation pathway. The findings suggest relationships between aspects of paternalistic leadership on both the motivational pathway and the health erosion pathway within the JD-R theory. The findings highlight the need to view paternalistic leadership from the three sub-leadership styles and suggest the role of paternalistic leadership aspects as antecedents to the JD-R theory pathways. Future studies could investigate the interactions of the three aspects of paternalistic leadership in influencing work outcomes. Future research could also investigate the moral leadership aspect within paternalistic leadership using a moral context (e.g., situations pertaining to honesty or integrity), with this not found to be significant in the JD-R theory. The use of a longitudinal approach and particularly, a three-wave method, would help to unravel the relationships involved.

Financial support

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.