Introduction

Charisma has traditionally been recognized as an individual’s innate ability to captivate and inspire others, often described as a natural gift of charm, magnetism, or likability (Weber, Reference Weber1947). However, contemporary research has aimed to demystify the concept and has established a more rigorous and practical definition (Antonakis, Bastardoz, Jacquart, & Shamir, Reference Antonakis, Bastardoz, Jacquart and Shamir2016; Reh, Van Quaquebeke, & Giessner, Reference Reh, Van Quaquebeke and Giessner2017). Specifically, charisma has been defined as ‘values-based, symbolic, and emotion-laden leader signaling’ that holds sway over followers (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Bastardoz, Jacquart and Shamir2016, p. 17). This charismatic symbolic signaling represents a powerful interpersonal skill set that enhances communication and collaboration (Antonakis, Fenley, & Liechti, Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011, Reference Antonakis, Bastardoz, Jacquart and Shamir2016; Niebuhr, Voße, & Brem, Reference Niebuhr, Voße and Brem2016). This charismatic symbolic signaling includes the use of both verbal and nonverbal embodied cues that enhance the impact, memorability, and overall impression of a message, thereby contributing to perceptions of charisma (Reh et al., Reference Reh, Van Quaquebeke and Giessner2017). The verbal cues construct and convey meaning by relating to the actual substance and content of the message (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011). The nonverbal cues accompany the verbal communication and refer to how the message is presented and delivered through body gestures, facial expressions, and animated vocal tones. This nonverbal delivery can convey confidence, empathy, and sincerity in a way that words alone may struggle to achieve, and thus, they contribute significantly to the perceived authenticity and trustworthiness of the message transmitter (Bonaccio, O’Reilly, O’Sullivan, & Chiocchio, Reference Bonaccio, O’Reilly, O’Sullivan and Chiocchio2016). People tend to respond strongly to nonverbal signals, making them an influential factor in how individuals are perceived. Thus, they are deemed essential to create a genuine and impactful presence that resonates with others on a deeper emotional level, which is central to charisma. Surprisingly, little attention has been paid to the effects of charismatic nonverbal cues beyond rhetorical cues (Hemshorn de Sanchez, Gerpott, & Lehmann‐Willenbrock, Reference Hemshorn de Sanchez, Gerpott and Lehmann‐Willenbrock2022; Reh et al., Reference Reh, Van Quaquebeke and Giessner2017). The current study uniquely narrows its focus to exclusively examine the nonverbal facets of charisma, which may either lack sufficient impact to influence perceived charisma or could be effective, warranting further investigation. Hence, the primary objective of this study is to demonstrate whether relying solely on nonverbal charisma signaling is sufficient to influence the perceived charisma of an individual.

Moreover, charisma is not confined to the individual; rather, it is a dynamic interplay between a charismatic figure and their followers or audience (Ito, Harrison, Bligh, & Roland-Lévy, Reference Ito, Harrison, Bligh, Roland-Lévy and Zúquete2020; Klein & House, Reference Klein and House1995); this interplay of mutual influences encompasses a person’s skills and exhibited behaviors with the perceptions and responses of others (Klein & Delegach, Reference Klein and Delegach2023; Wegge, Jungbauer, & Shemla, Reference Wegge, Jungbauer and Shemla2022). Specifically, the individual behaviors impact the perception and reactions of the observers, and the presence of observers influences the individual’s behavior, as the awareness of being scrutinized prompts self-conscious adjustments to actions (Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver and Scheier1981). Thus, we suggest that the presence of others, i.e., an audience, may play a role in charismatic nonverbal display as in front of an audience, the person becomes more aware of their delivery of nonverbal cues, adding a second valuable contribution to the body of charisma literature.

Practically, it is crucial for individuals and organizations to enhance and refine methods for the development of charisma. Charismatic managers often have the capacity to engage and energize teams, driving higher levels of productivity and fostering a positive work environment (e.g., Fest, Kvaløy, Nieken, & Schöttner, Reference Fest, Kvaløy, Nieken and Schöttner2021) and are more effective communicators in various contexts, from negotiations to public speaking (Eman, Hernández, & González-Romá, Reference Eman, Hernández and González-Romá2024). Hence, this study introduces an innovative virtual reality (VR) intervention technique that is based on nonverbal charismatic signaling (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Bastardoz, Jacquart and Shamir2016) and self-awareness theories (Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver and Scheier1981) to cultivate and accelerate the development of charisma. VR provides a powerful tool for skills development by immersing users in dynamic, lifelike scenarios that enhance situational experiences through responsive virtual environments, making it an effective method for refining charismatic skills (Valls-Ratés et al., Reference Valls-Ratés, Niebuhr and Prieto2023). Therefore, the third goal of this study is to introduce a new intervention that capitalizes on VR’s swiftness, convenience, cost-effectiveness, and efficacy to leverage nonverbal communication strategies and simulate audience contexts.

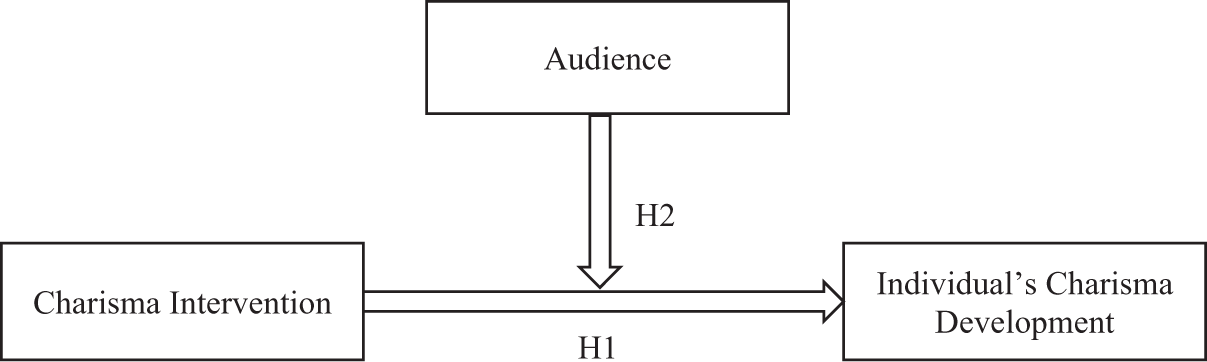

In summary, this study makes three significant contributions to the literature. First, this study aims to highlight the unique impact of nonverbal tactics on perceptions of charisma, distinguishing itself from a large body of charisma literature, which predominantly focuses on charismatic rhetoric (Fischer & Sitkin, Reference Fischer and Sitkin2023; Liegl, Maran, Kraus, Furtner, & Sachse, Reference Liegl, Maran, Kraus, Furtner and Sachse2024). Second, the study suggests and explores the impact of audience presence on the display of nonverbal charisma cues. Finally, the study introduces a novel, short-term, nonverbal-based charisma intervention using VR and evaluates its feasibility and effectiveness. Figure 1 presents the conceptual research model.

Figure 1. The conceptual research model.

Theoretical development and hypotheses

Charisma development

By understanding charisma as a symbolic signaling, researchers have identified specific verbal and nonverbal behaviors that directly contribute to how charismatic an individual is perceived (Tskhay, Zhu, & Rule, Reference Tskhay, Zhu and Rule2017). Followers actively process and interpret the communicator’s verbal and nonverbal signals and subsequently evaluate the communicator’s charisma (Maran, Reference Maran2024; Tskhay, Xu, & Rule, Reference Tskhay, Xu and Rule2014, Reference Tskhay, Zhu and Rule2017). Specifically, verbal communication, including the content of words, ideas, and messages conveyed by a charismatic individual, is pivotal in shaping the perception of charisma (Akstinaite, Jensen, Vlachos, Erne, & Antonakis, Reference Akstinaite, Jensen, Vlachos, Erne and Antonakis2024; Charteris-Black, Reference Charteris-Black2005; Emrich, Brower, Feldman, & Garland, Reference Emrich, Brower, Feldman and Garland2001; Fest et al., Reference Fest, Kvaløy, Nieken and Schöttner2021; Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Rohner, Bornet, Carron, Garner, Loupi and Antonakis2023; Mio, Riggio, Levin, & Reese, Reference Mio, Riggio, Levin and Reese2005). By employing compelling rhetoric, metaphors, persuasive speeches, visionary ideas, engaging storytelling, and emotionally resonant language, the individual’s message deeply resonates with the audience, enhancing its impact and memorability.

On the other hand, nonverbal communication refers to the delivery of the content and encompasses aspects of interaction that are not conveyed through words, such as facial expressions, body gestures, and vocal tone (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011, Reference Antonakis, Bastardoz, Jacquart and Shamir2016; Levine, Muenchen, & Brooks, Reference Levine, Muenchen and Brooks2010). Charismatic individuals utilize specific nonverbal techniques to enhance their impact. For example, they employ open-hand gestures and lean toward the audience to create a sense of connection and engagement (e.g., Talley & Temple, Reference Talley and Temple2015); use facial expressions like smiling and maintaining eye contact to boost likability and credibility (e.g., Liegl et al., Reference Liegl, Maran, Kraus, Furtner and Sachse2024); and adopt an animated voice tone, characterized by vocal fluency and the avoidance of hesitations, to captivate the audience and emphasize their message (Aharonson, Malachi, & Katz-Navon, Reference Aharonson, Malachi and Katz-Navon2023; Niebuhr et al., Reference Niebuhr, Voße and Brem2016; Suen & Hung, Reference Suen and Hung2024). These nonverbal strategies help convey passion, confidence, and authenticity, thereby garnering support for their message (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011; Bono & Ilies, Reference Bono and Ilies2006; Caspi, Bogler, & Tzuman, Reference Caspi, Bogler and Tzuman2019; Frese, Beimel, & Schoenborn, Reference Frese, Beimel and Schoenborn2003; Tskhay et al., Reference Tskhay, Zhu and Rule2017).

The literature features ongoing discussions regarding the relative contributions of message content and delivery to charisma perceptions. Both the message content (verbal communication) and delivery (nonverbal communication) contribute to the message’s impact and memorability (Charteris-Black, Reference Charteris-Black2005; Emrich et al., Reference Emrich, Brower, Feldman and Garland2001; Mio et al., Reference Mio, Riggio, Levin and Reese2005). However, nonverbal communication is immediate and can activate an overarching schema or prototype of implicit beliefs about charismatic individuals, thereby priming the perception of someone’s charisma (Schuller et al., Reference Schuller, Amiriparian, Batliner, Gebhard, Gerczuk, Karas and Löchner2023). Individuals instantly and effortlessly perceive various characteristics from others’ appearance and brief ‘thin slices’ of their nonverbal behaviors (Tskhay & Rule, Reference Tskhay and Rule2013). For example, leaders’ faces (Rule & Tskhay, Reference Rule and Tskhay2014), clothing style (Maran, Liegl, Moder, Kraus, & Furtner, Reference Maran, Liegl, Moder, Kraus and Furtner2021), eye-directed gaze (Liegl et al., Reference Liegl, Maran, Kraus, Furtner and Sachse2024), and specific camera angles (Hoffmann, Maran, & Marin, Reference Hoffmann, Maran and Marin2023) significantly impacted the perceived charisma of an individual.

Moreover, delivery plays a crucial role, often taking precedence over content (Bonaccio et al., Reference Bonaccio, O’Reilly, O’Sullivan and Chiocchio2016; Hall, Bernieri, & Carney, Reference Hall, Bernieri, Carney, Harrigan, Rosenthal and Scherer2005; Niebuhr et al., Reference Niebuhr, Voße and Brem2016; Shim, Livingston, Phillips, & Lam, Reference Shim, Livingston, Phillips and Lam2021). The initial impression formed by individuals is primarily shaped by the rapid processing of delivery (for instance, facial expressions are processed holistically and categorized rapidly, often within 100 ms), which offers the first glimpse of charisma, whereas content is processed more gradually (for example, it is typically processed at an average rate of about three words per second; Trichas, Schyns, Lord, & Hall, Reference Trichas, Schyns, Lord and Hall2017). The first impression created by the nonverbal cues can eventually lead to a perception that is either compatible or incompatible with the following message content (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Bogler and Tzuman2019). In situations where verbal and nonverbal cues are incongruent, individuals tend to rely more on the latter (Remland, Reference Remland1981). This highlights the significance of delivery in charismatic interactions: it captures attention, creates an emotional impact, and establishes an immediate connection with the audience (Riggio, & Crawley, Reference Riggio, Crawley, Sternberg and Kostić2022). Therefore, we propose that the nonverbal cues of the message delivery, through their rapid processing and immediate impact, hold significant sway in shaping perceptions of charisma.

Our research centers exclusively on the three nonverbal charisma tactics (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011) and proposes that they alone may be sufficient to cultivate and enhance perceived charisma in individuals. Thus, it takes a different angle from previous approaches to charisma development that focus primarily on the active training of managers with specific verbal charismatic techniques (e.g., Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011; Towler, Reference Towler2003). We specifically refer to the use of body gestures, facial expressions, and an animated voice tone, suggesting that training in these specific nonverbal tactics can lead individuals to adopt certain stances, gestures, and expressions, thereby being perceived as more charismatic.

Audience presence

Charisma, by its very definition, involves at least a dyadic relationship, as it is always practiced in the presence of others (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Harrison, Bligh, Roland-Lévy and Zúquete2020; Klein & House, Reference Klein and House1995), i.e., the influence of the charismatic individual on others’ attitudes and behaviors. However, our study takes a novel perspective. We propose that through a spiral process, the presence of others contributes to the development of the individual’s charisma. Specifically, when individuals are aware of the presence of others, they shift their focus inwardly (Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver and Scheier1981; Chon & Sitkin, Reference Chon and Sitkin2021). This self-focused attention involves heightened mindfulness of self-relevant information, including bodily states, thoughts, emotions, beliefs, attitudes, and memories (Ingram, Reference Ingram1990). As people become more attentive and self-aware, they develop a greater consciousness of their own presence, attributes, and feelings (Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver and Scheier1978). Consequently, they become better at evaluating their bodily responses, such as the intensity of their physical reactions (Baltazar et al., Reference Baltazar, Hazem, Vilarem, Beacousin, Picq and Conty2014; van Meurs, Greve, & Strauss, Reference van Meurs, Greve and Strauss2022). Therefore, the presence of an audience heightens sensitivity to both observable and private aspects of the self, such as bodily self-awareness (Conty, George, & Hietanen, Reference Conty, George and Hietanen2016; Oda, Niwa, Honma, & Hiraishi, Reference Oda, Niwa, Honma and Hiraishi2011). Specifically, an audience stimulates a drive state in the performer, increasing their energy and self-awareness (Innes & Young, Reference Innes and Young1975). This heightened self-awareness creates a feedback loop by enhancing individuals’ sensitivity to potential discrepancies between their current and their desired behaviors (Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver and Scheier1981), which helps them align their behaviors more closely with the ideal (e.g., charismatic) behaviors.

A VR intervention to improve charisma

In order to examine whether individuals can improve their charisma solely by developing the three nonverbal charismatic tactics (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011), the current study develops and tests a new VR intervention aimed at charisma improvement. VR creates a realistic psychological experience that enables the perception of being physically present in a virtual environment (Rebelo, Noriega, Duarte, & Soares, Reference Rebelo, Noriega, Duarte and Soares2012). Wearing a VR headset simulates a three-dimensional perception of depth while presenting an interactive image that responds to the movement of the head to create the illusion of looking around (Lindner et al., Reference Lindner, Miloff, Hamilton, Reuterskiöld, Andersson, Powers and Carlbring2017). Thus, users have the opportunity to experience virtual situations in ways that closely resemble corresponding real-world scenarios. This heightened sense of presence has been identified as a key factor contributing to the effectiveness of learning with VR applications and a significant advantage of VR compared to other training methods (Hubbard & Aguinis, Reference Hubbard and Aguinis2023).

An additional advantage of VR technology is that it serves as a fast, cost-effective, and accessible training tool. It allows users to engage in diverse, controlled scenarios from any location, significantly reducing the time and costs associated with traditional training methods and its scalability makes it easy to implement across large groups, further enhancing its affordability and accessibility.

Moreover, VR technology excels in simulating the experience of addressing an audience without the need for a live crowd. By creating a highly realistic scenario, VR provides participants with an immersive experience that feels genuinely authentic, as if they are actually standing before an audience (Davis, Linvill, Hodges, Da Costa, & Lee, Reference Davis, Linvill, Hodges, Da Costa and Lee2020). This realism is crucial, as studies indicate that speakers react similarly to both virtual and real audience and the training in front of a virtual audience is as effective as training in front of a real audience but with a reduction in reported anxiety levels (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Linvill, Hodges, Da Costa and Lee2020; Kroczek & Mühlberger, Reference Kroczek and Mühlberger2023; Pertaub, Slater, & Barker, Reference Pertaub, Slater and Barker2002).

Specifically to charisma training, VR creates a unique setup that enables an excellent opportunity to practice charisma tactics. First, it helps speakers switch from rehearsing in a sterile ‘memorization mode’ to presenting in an expressive, audience-oriented ‘communication mode’. Second, VR allows for the creation of spacious rooms with a perceived distance between the speaker and the virtual audience. This perceived distance encourages speakers to project their voices more effectively, speak at a higher pitch level, and demonstrate a fuller and stronger voice quality (Niebuhr & Tegtmeier, Reference Niebuhr, Tegtmeier, Baierl, Behrens and Brem2019).

Thus, we propose that the VR charisma training intervention increases the perceived individual’s charisma compared to a control condition, especially with an audience presence. We hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1: Charisma is developed through a short, highly focused VR intervention structured around the three nonverbal charisma tactics (body gestures, facial expressions, and animated voice tone).

Hypothesis 2: The increase in charisma is more pronounced when training in front of a VR audience than when training without the audience’s presence.

Methodology

Design and participants

In order to test our hypotheses and the efficacy of the new charisma intervention, while increasing our ability to infer causality, we designed a controlled, randomized laboratory experiment. Specifically, the design consisted of a full 2 (experimental condition – charisma training and control condition – kickboxing training) × 2 (VR hall with an audience present and VR hall without an audience) between experimental design with a pre- (Time 1) and a post- (Time 2) tests within measurements of charisma.

The study was conducted in accordance with the following ethical procedure; ethics approval was obtained from the first author’s Institutional Review Board prior to commencing the study (Approval Number: P_2021109). Participants provided informed consent, wherein they were informed about the purpose of the research, the procedures involved, potential benefits, confidentiality measures, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequences. Furthermore, participants were informed that their speeches would be recorded and later presented as part of a separate research study, and they were asked to provide their consent by signing a permission form. All data collected were handled anonymously and stored securely to ensure confidentiality.

Participants were recruited in Israel through snowball convenience sampling to take part in research regarding ‘public speaking in virtual reality’. Snowball sampling is a recognized and viable method of recruiting study participants not easily accessible or known to the researcher (e.g., Naderifar, Goli, & Ghaljaie, Reference Naderifar, Goli and Ghaljaie2017). This method involved the researcher contacting initial participants, who then refer others to the study, and also leveraging social media to reach potential participants (Parker, Scott, & Geddes, Reference Parker, Scott, Geddes and Atkinson2019). For their participation, they were offered a short digital course of their choice between storytelling or how to incorporate humor in presentations.

The final sample included 121 Hebrew-speaking participants (42 males, 78 females, and one other), ages ranged between 21 and 67 years (M = 38.75 years, SD = 11.24), and various education levels (4.1% without high school diploma, 19% with high school diploma, 40.5% BA degree, and 36.4% MA degree). This diversity in age, gender, and educational background helps ensure that our sample represents a relatively broad population.

Those who expressed interest were provided with a link to online questionnaires (Time 0) and were asked to sign a consent form and complete the public speaking anxiety and Big Five personality traits questionnaires before arriving at the laboratory. Additionally, participants were requested to prepare a 2-min speech (in Hebrew) about an enjoyable experience they would recommend. Specific times and dates were scheduled for their laboratory visit.

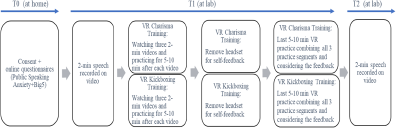

Upon arrival, participants were randomly assigned to one of the four experimental conditions. They first presented their preprepared 2-min speech, which was recorded on video by the researcher (Time 1). Next, they received an Oculus VR headset with instructions on how to use it, which started the training session outlined in Fig. 2. The training session comprised three rounds, during which participants watched VR explanatory videos lasting 2–3 min. After watching each video, participants practiced the learned techniques for 5–10 min, either in front of a virtual audience or in an empty virtual hall. At the end of the third round, participants took off the VR headset. They watched their 2-min initial recorded speech and set themselves improvement goals based on what they had just learned. This was followed by a fourth and final round of VR practice. After this feedback session, participants put on the VR headset for their fourth practice session, which lasted another 5–10 min. During this final practice, participants integrated the feedback they had given themselves into their performance, applying it to all three segments of the training. The entire VR training round lasted approximately 45 min. Finally, participants were asked to present the same initial 2-minute speech again and were video recorded by the researcher (Time 2).

Figure 2. The study procedure and timeline for both the experimental and control groups.

A total of 242 recorded videos were obtained, capturing both Time 1 and Time 2 speeches. The first 30 s of each video were trimmed as research indicates that even brief observations of 5–10 s of nonverbal behavior can effectively predict an individual’s perceived charisma (Tskhay et al., Reference Tskhay, Zhu and Rule2017).

Next, to evaluate the charisma of the trainees, we recruited an additional sample of participants from the Prolific online system, totaling 355 non-Hebrew-speaking individuals. This sample demographics were as follows: 53.24% females, 45.35% males, and 1.41% other, ages ranging between 18 and 79 years (M = 34.73 years, SD = 13.49). Each participant was shown 8 random videos, with the condition that no speaker’s Time 1 and Time 2 speech was rated by the same online participant. Employing non-Hebrew-speakers or individuals unfamiliar with the speakers’ language to rate the videos ensured a focus on nonverbal cues, effectively neutralizing the impact of verbal content during the evaluation process. Each video was rated by 9–14 different online participants.

The intervention

Experimental condition: The VR charisma training included three 2–3-min videos featuring explanations and demonstrations, each designed around one of the three nonverbal charismatic tactics (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011). Specifically, training about (1) body gestures that help to convey a message, such as open-hand movements (Frese et al., Reference Frese, Beimel and Schoenborn2003; Towler, Reference Towler2003); (2) facial expressions, for example, eye contact and smiling (Frese et al., Reference Frese, Beimel and Schoenborn2003; Towler, Reference Towler2003; Tskhay et al., Reference Tskhay, Zhu and Rule2017); and (3) animated voice tone, such as maintaining vocal fluency and avoiding hesitation (Valls-Ratés et al., Reference Valls-Ratés, Niebuhr and Prieto2023).

Control condition: To enhance the internal validity of the experiment and ensure that any observed effects are specifically related to the nonverbal elements of the charisma training rather than general body awareness, we added a control condition. This control condition aimed to eliminate potential alternative explanations related to practice opportunities or the confounding influence of physical activity, which involves active engagement, focus, and body movements (e.g., posture, stance, and expressions) that may increase awareness of the body. Furthermore, we aimed to create a similarity in engagement levels, that would help maintain participants’ attention, commitment, motivation, and interest. To achieve this, we designed an alternative training focused on body movements centered around kickboxing. The kickboxing training took place in the same VR halls as the charisma training and it followed a similar structure, consisting of three 2–3-min videos demonstrating various kickboxing movements, such as basic punches and kicks. After watching each video, participants practiced the newly learned movements for 5–10 min, either in front of a virtual audience or in an empty virtual hall. Thus, the specific focus of the two training methods differs, yet there could be transferable skills or habits related to body movements in kickboxing that can be compared with explicit nonverbal charisma tactics training.

To manipulate the audience presence condition, we used a VR headset to simulate a large hall setting. In the audience condition, participants practiced standing on a stage in front of a virtual hall filled with 1,000 people, while in the no-audience condition, they practiced standing on the same stage but in front of empty seats. See the Appendix for still images of the full and empty halls.

Measures

All questionnaires filled out by participants were translated to Hebrew with the usual precautions of forward and backward translation by independent translators.

Charisma was measured using two scales: (1) MLQ 5X attributed charisma subscale (Bass & Avolio, Reference Bass and Avolio1990), which included 4 items (e.g., ‘To what extent the person in the video manifests power and confidence’, α = .94) on 5-point Likert scales (1 – Not at all, 5 – Very much); and (2) a 1-item prompt of general charisma (‘How charismatic is this person?’; Maran, Furtner, Liegl, Kraus, & Sachse, Reference Maran, Furtner, Liegl, Kraus and Sachse2019; Tskhay et al., Reference Tskhay, Zhu and Rule2017) using a 100-point scale (1 = Not at all charismatic, 100 = Very charismatic).

Controls all the following scales were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. Public Speaking Anxiety. We controlled for public speaking anxiety because it can cause people to exhibit tense body language, avoid eye contact, or appear visibly uncomfortable (Hofmann, Gerlach, Wender, & Roth, Reference Hofmann, Gerlach, Wender and Roth1997). It was measured at T0 using the PSAS scale (Bartholomay & Houlihan, Reference Bartholomay and Houlihan2016) that included 17 items (α = .93). Big Five personality traits. We controlled for the Big Five personality traits because previous studies have demonstrated their association with charisma (e.g., Banks et al., Reference Banks, Engemann, Williams, Gooty, McCauley and Medaugh2017). We used the Big Five Inventory-10 (Rammstedt & John, Reference Rammstedt and John2007). Results of a confirmatory factor analysis revealed that a six-factor model with public speaking anxiety, extraversion, neuroticism, openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness scales as separate factors demonstrated an acceptable fit level (χ2(280) = 391, p < .01, CFI = .92, TLI = .90, RMSEA= .06).Footnote 1

Data analysis approach

First, we calculated descriptive statistics using SPSS (Version 23). Second, changes in perceived participant charisma (i.e., general charisma and attributed charisma) from Time 1 to Time 2 were represented as a within-person variable by the inclusion of time as a predictor, indicating the extent to which the perceived charisma changed in a single person from the pre- to the post-training measurement time. Thus, given that the data was collected at two points in time, wherein measurements over time were nested within individuals, we applied a mixed model analysis using the jamovi GAMLj module (Gallucci, Reference Gallucci2019). Mixed models are particularly suitable for analyzing data with repeated measures. They handle nested or hierarchical data structures and account for correlations between observations within the same individual. This capability is crucial when the assumption of independence between observations is violated (Raudenbush & Bryk, Reference Raudenbush and Bryk2002). Finally, we conducted simple slope analyses to gain a clearer understanding of the effects of the interaction.

Results

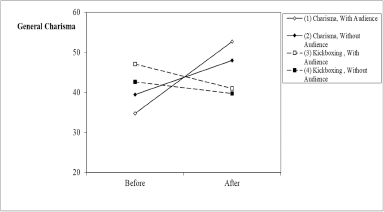

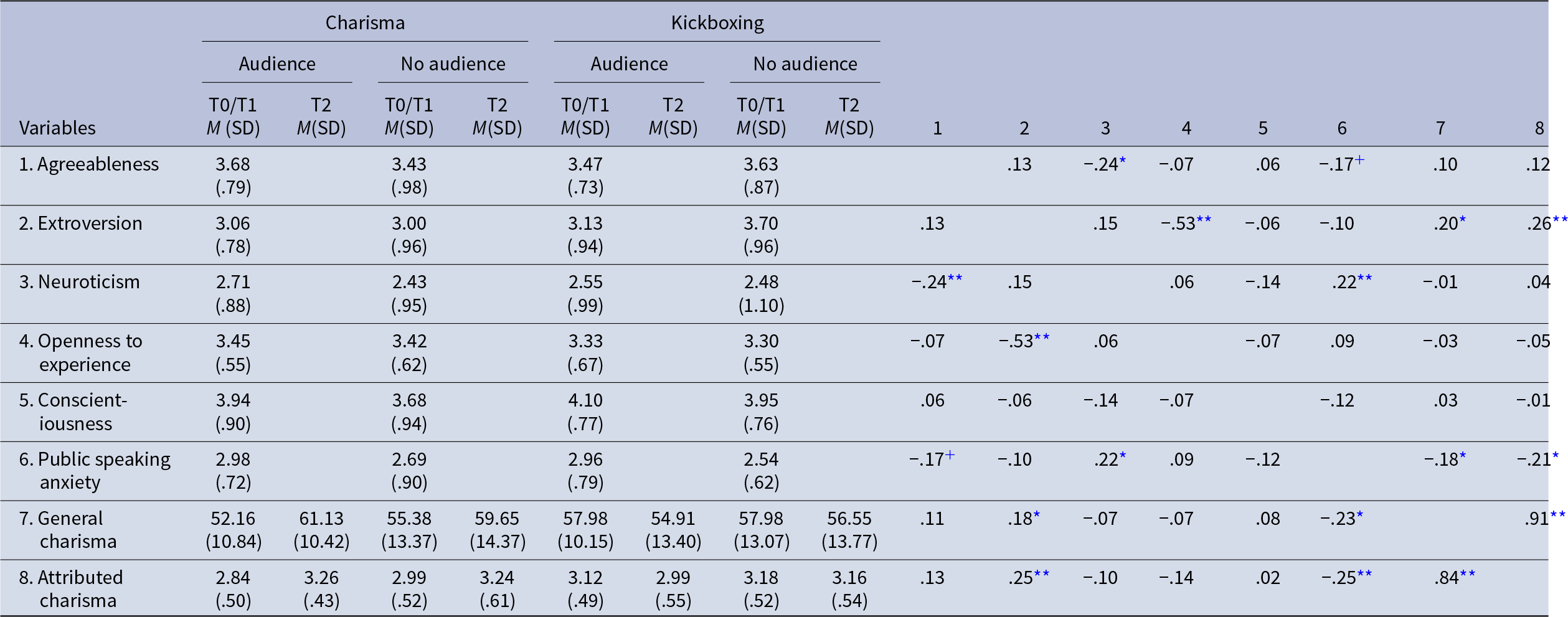

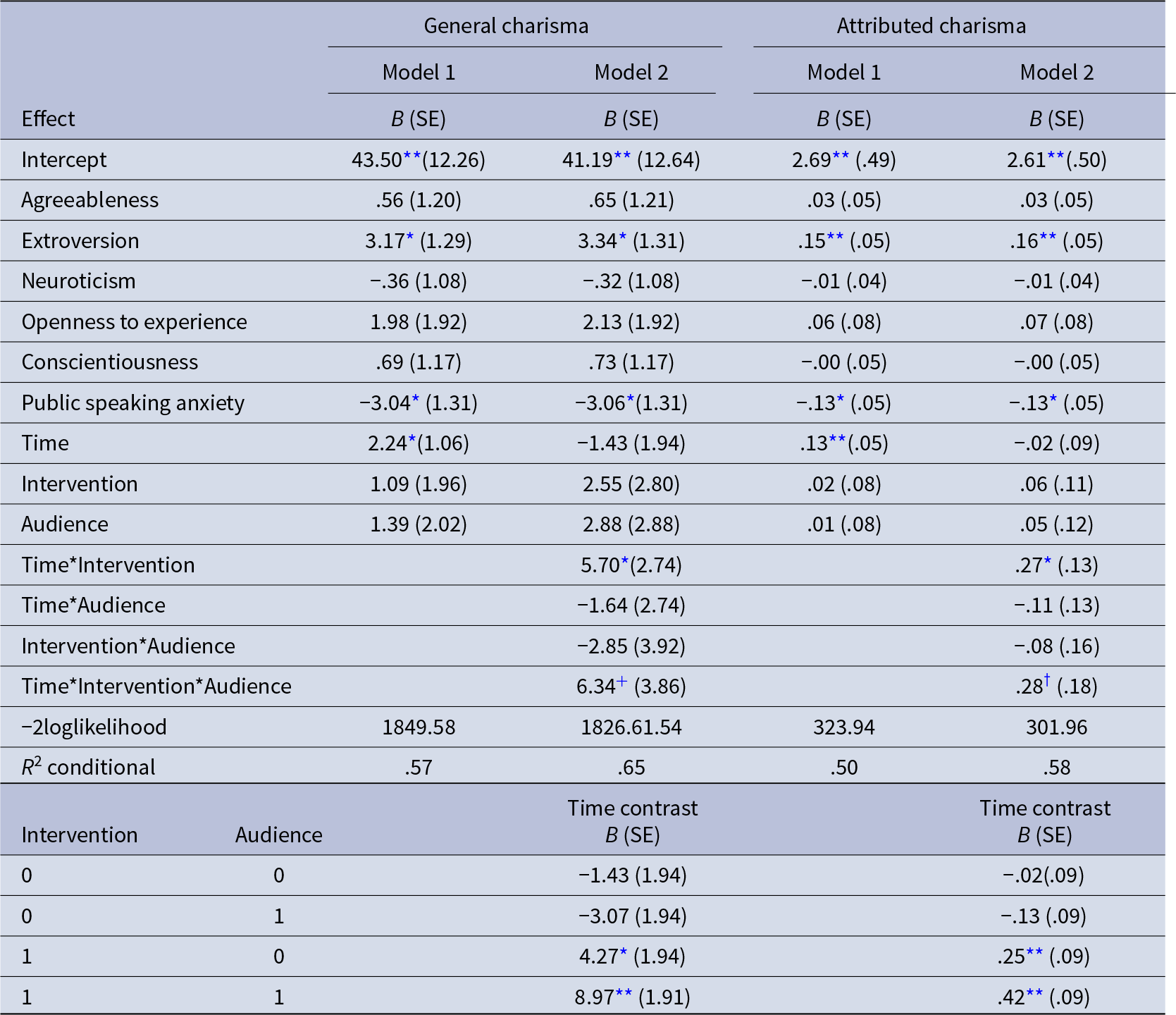

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations among the study variables. First, we conducted the following mixed-model regressions: perceived participants’ charisma on the control variables (i.e., participant’s Big Five traits, and public speaking anxiety) and the three main effects (time, intervention type, and audience presence; see Table 2, Models 1). Second, we added the three two-way interactions, and the three-way interaction of time, intervention type, and audience presence (see Table 2, Models 2). For general charisma, results demonstrated that the three-way interaction (B = 6.34, SE = 3.86, p = .10) was not significant at the conventional p < .05 level, but attained significance at p = .10. In addition, Model 2 differed significantly from Model 1 (Δ-2loglikelihood = 22.97, p < .01). Figure 3 depicts the three-way interaction. Simple slope analyses demonstrated that there were significant increases in general charisma for both charisma training groups with audience presence (B = 8.97, SE = 1.91, p < .01) and without audience presence (B = 4.27, SE = 1.94, p < .05). There were no significant changes in general charisma for the kickboxing groups (with audience B = −3.07, SE = 1.94, n.s, and without audience B = –1.43, SE = 1.94, n.s.). The beneficial effect of charisma training was more prominent for the group with audience presence than for the group with no audience presence (B = 4.70, SE = 2.65, p = .08).

Figure 3. Perceived general charisma as a function of time, intervention, and audience presence.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables

Note: N = 121. Correlations in Time 1 are presented in the lower triangle; correlations in Time 2 are shown in the upper triangle.

+ p < .10,

* p < .05. **p < .01.

Table 2. Multilevel mixed-model analyses of charisma on time, intervention, and audience presence

Note: N = 121. Time: 0 – before; 1 – after. Intervention: 0 – kickboxing training; 1 – charisma training. Audience: 0 – no audience present; 1 – audience present.

† p = .12.

+ p ≤ .10.

* p < .05. **p < .01.

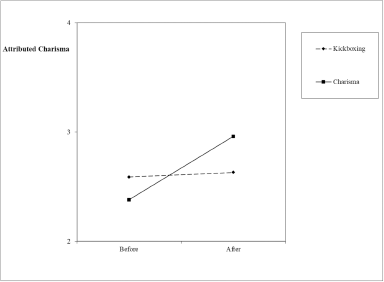

For attributed charisma, results demonstrated that the three-way interaction (B = .28, SE = .18, p = .12), although not significant at the conventional p < .05 level, was close to significance. Model 2 differed significantly from Model 1 (Δ-2loglikelihood = 21.98, p < .01). The simple slope analyses demonstrated that similarly to general charisma, there were significant increases in attributed charisma for the charisma training groups with audience presence (B = .42, SE = .09, p < .01) and without audience presence (B = .25, SE = .09, p < .01). There were no significant changes in attributed charisma for the kickboxing groups (with audience B = −.13, SE = .09, n.s. and without audience B = −.02, SE = .09, n.s.). However, there was no significant difference between the slopes of the two charisma training groups (B = .17, SE = .13, n.s.). Thus, we focused on the two-way interaction between time and intervention on attributed charisma (see Fig. 4), which was significant (B = .27, SE = .13, p < .05). Subsequent simple slope analyses revealed a significant increase in participants’ attributed charisma from Time 1 to Time 2 within the charisma-trained groups (B = .33, SE = .06, p < .01), which was not observed in the kickboxing groups (B = −.08, SE = .06, n.s.).

Figure 4. Perceived attributed charisma as a function of time and intervention.

Discussion

Charismatic individuals possess distinctive personal skills and use charismatic communication that can have powerful effects on their followers; however, while much of the existing research has focused on charismatic rhetoric, the current study highlights the unique impact of nonverbal tactics on perceptions of charisma. The results of a pre- and post-test intervention and control groups experimental design showed that participants in the charisma intervention group did increase their perceived charisma significantly compared to the control group. This effect was more prominent for participants who practiced in front of a virtual audience. The randomly assigned control group that went through a different yet relevant body movement VR intervention did not show a change in their perceived charisma level.

These results contribute distinctive and substantial additions to the existing literature in several meaningful ways. While much of the existing research has centered on how verbal elements like persuasive language and storytelling shape charisma perceptions (Fischer & Sitkin, Reference Fischer and Sitkin2023; Liegl et al., Reference Liegl, Maran, Kraus, Furtner and Sachse2024), the current study provides a fresh perspective by demonstrating that nonverbal cues solely – such as gestures, facial expressions, and vocal tone – play a critical role in how charisma is perceived. By doing so, it expands the theoretical understanding of charisma, highlighting the importance of embodied communication in leadership and encouraging future research to explore these underrepresented dimensions.

Second, this study sheds new light on the impact of audience presence on the display of nonverbal charisma cues. Our results suggested, emphasizing the dynamic interplay between charismatic individuals and their observers, that the mere presence of an audience can alter or amplify the expression of nonverbal behaviors that convey charisma. However, these results were not significant at the conventional p < .05 levels, but were approaching that, which may raise questions about the consistency and reproducibility of the influence of audience presence. These findings regarding the impact of audience presence may be attributed to various potential explanations: Individuals experience heightened arousal and self-consciousness when they perform in front of an audience, which, in turn, influences their performance (Chon & Sitkin, Reference Chon and Sitkin2021). However, in the current study, participants in the no-audience condition also practiced standing on a stage but in front of an empty hall. This setting may likewise direct attention inward and increase self-awareness (Carver & Scheier, Reference Carver and Scheier1981; Chon & Sitkin, Reference Chon and Sitkin2021), which could have also amplified performance. In addition, the presence of an audience can be significant to charisma development because the audience provides feedback to the speaker, allowing them to gauge their effectiveness in real-time (El-Yamri, Romero-Hernandez, Gonzalez-Riojo, & Manero, Reference El-Yamri, Romero-Hernandez, Gonzalez-Riojo and Manero2019). An important factor within technology-mediated communication is social presence, which refers to the extent to which individuals perceive virtual others as physically ‘real’ (Kreijns, Xu, & Weidlich, Reference Kreijns, Xu and Weidlich2022; Weidlich & Bastiaens, Reference Weidlich and Bastiaens2019). This sense of presence is crucial in contexts such as charisma training, where the audience’s presence can significantly impact performance. Indeed, previous studies have shown that a live audience enhanced public speaking performance by increasing speakers’ arousal and engagement (El-Yamri et al., Reference El-Yamri, Romero-Hernandez, Gonzalez-Riojo and Manero2019). However, in our study, due to budgetary constraints, the audience was depicted as static and silent, potentially diminishing the realism and vibrancy of the audience images. This limitation may have led participants to perceive the virtual audience as less ‘real’ or authentic, resulting in lower levels of social presence and toning down the effects on performance. Understanding these nuances is essential for interpreting the outcomes of VR-based studies. As VR research, particularly in the field of leadership, is still progressing, future research should aim to address these limitations by creating more dynamic and interactive virtual audiences to better simulate real-world conditions and examine their impact on behavioral and psychological responses.

Finally, the purpose of this study was to determine whether a short VR-based training intervention could be effective in charisma development. By demonstrating the malleability of charisma, this study reaffirmed the idea that charisma can indeed be cultivated, even at a pace that surpasses conventional assumptions drawn from prior research (Antonakis et al., Reference Antonakis, Fenley and Liechti2011). The introduction of a novel, short-term intervention using VR for training in nonverbal charismatic communication represents a pioneering advancement. This VR-based approach is both innovative and practical, as it assesses the feasibility and effectiveness of the intervention. By offering a cost-effective, scalable, and immersive method for developing charismatic skills, it adds a valuable tool to the field and opens up possibilities for future research and application.

Limitations and future research

The current study employs a robust experimental design that includes pre- and post-training measurements of charisma in both experimental and control groups, utilizing data from two different sources. However, the study has several limitations that present opportunities for future research. First, we assessed charisma before and immediately after the training sessions. This immediate post-training measurement provides valuable insights into the short-term efficacy of the intervention, but it may not fully capture the potential long-term impacts that could develop over time. To expand our understanding, future research should examine the durability of the effects of charisma training over an extended timeframe, shedding light on any potential long-term impact that might emerge beyond the immediate post-training period. Such an approach offers a more comprehensive perspective on the lasting benefits of charisma training and its enduring influence on individuals’ interpersonal interactions and communication skills.

Second, this study focused on charisma exclusively within a leader-centered leadership context. To enhance our understanding of the charisma phenomenon, future research should extend the scope of research by investigating how followers react to shifts in a leader’s charisma. Understanding how nonverbal charisma training impacts followers’ performance could prove crucial in validating the extent to which charisma has truly developed. This avenue of investigation may provide valuable insights into the ripple effects of charismatic training on various facets of organizational dynamics, thus enhancing our understanding of the broader implications of charisma development.

Practical implications

The findings of this study offer a practical and cost-effective tool that organizations can readily deploy to foster leadership development across all organizational tiers. Beyond improving on mere charm or charisma for its intrinsic appeal, charisma training centers on nurturing competencies that pave the way for personal development. Importantly, this development is not contingent on the specific skills of a coach or researcher. This insight presents an accessible avenue for organizations to strategically invest in their leaders’ growth and efficacy.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of the practice environment is intricately linked to the realism of audience portrayal (El-Yamri et al., Reference El-Yamri, Romero-Hernandez, Gonzalez-Riojo and Manero2019). It has been observed that people remain engaged in situations despite the inadequate representation and subpar quality of virtual individuals who lack responsive behaviors (Pertaub et al., Reference Pertaub, Slater and Barker2002). Notably, the realm of VR possesses immense potential as a conduit for training and interventions, offering almost limitless opportunities for simulating diverse scenarios. For instance, it can be tailored to create specific scenarios (e.g., simulating the impact of a ringing cell phone or an individual leaving the hall) or gradually escalating levels of challenge (Botella, Garcia-Palacios, Baños, & Quero, Reference Botella, Garcia-Palacios, Baños and Quero2009). Additionally, VR technology affords the capability to provide comprehensive, analytical, and objective feedback to participants. This feedback could be channeled through audience responses or harnessed via AI-driven speaker behavior analysis encompassing factors such as eye contact, speech rate, and the use of hesitation words. Notably, the technological infrastructure to offer real-time feedback during or after practice already exists, offering the potential for meaningful enhancements to training and practice sessions.

Conclusion

Charismatic individuals have an impact on others’ behaviors and attitudes, making the development of charisma a critical focus for both theorists and practitioners. The current study demonstrates charisma can be developed through nonverbal tactics and introduces a new brief and cost-effective tool for cultivating charisma. By that, we contribute to the field by offering a practical and accessible method for enhancing charismatic leadership, which has significant implications for both theoretical understanding and real-world applications.

Conflict(s) of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Example of the VR audience environment