1. Introduction

Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) systematic distinction between what is said and what is meant paved the way for pragmatics to become a discipline independent from semantics. Although he presents a layout of four individual maxims, Grice (Reference Grice1989: 371) argues that ‘[t]he suggested maxims do not seem to have the degree of mutual independence of one another which the suggested layout seems to require’. Scholars have subsequently devised approaches based on two principles (e.g. Horn Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006), three principles (e.g. Levinson Reference Levinson1987, Reference Levinson1991) and one principle (e.g. Kasher Reference Kasher and Kasher1976, Reference Kasher1982; Sperber & Wilson Reference Sperber and Wilson1995; Wilson & Sperber Reference Wilson and Sperber2012). However, no consensus has been reached regarding which maxims belong together, can be subsumed under another, play a superior role or serve as precondition for the others. Moreover, the vagueness of the concept of relevance has led to a variety of misunderstandings and circularities within influential approaches. While Levinson (Reference Levinson1989) identifies some of these circularities in the influential relevance theory of Sperber & Wilson (Reference Sperber and Wilson1995), I argue in Section 2.2.3 that Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) wording of ‘as (is) required’ itself also suggests relevance dependency in a circular manner, contributing to the widespread assumption of an alleged interdependence between the maxims of relevance and quantity.

This paper addresses several controversies regarding Grice’s principles, including their formulation as imperative guidelines directed at speakers, Grice’s notion of ‘saying’, the assumption of truthfulness as a precondition for the operation of the other principles, the vagueness of relevance, and alleged interdependences among the principles, particularly between informativeness and relevance. I provide a revision of both Grice’s cooperative principle and his four principles – truthfulness, relevance, informativeness and clarity – and extend them by introducing a fifth principle of social conformity, abbreviated as the TRICS-Principles. I address controversies associated with each principle, particularly those contributing to assumptions of interdependence, refine the definitions of certain principles where necessary, and demonstrate the independent operation of the principles.

The structure of this paper is as follows. In Section 2.1, I slightly revise both Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) cooperative principle and his four maxims addressed to speakers in the imperative. I then demonstrate the operation of each principle in detail in the corresponding subsections of Section 2.2. In Section 2.2.1, I engage with the debate concerning Grice’s notion of saying, necessitating a reformulation of the principle of truthfulness (T-Principle), and defend the position that truthfulness is not a precondition for the felicitous operation of the other principles. Instead, I demonstrate the extent to which the other principles may operate under the umbrella of a flouted T-Principle. Sections 2.2.2 and 2.2.3 provide revised definitions of the principles of relevance (R-Principle) and informativeness (I-Principle) and demonstrate their independence from each other. Section 2.2.4 highlights how the clarity principle (C-Principle) operates independently of the other principles, particularly of the R-Principle. Finally, Section 2.2.5 introduces the principle of social conformity (S-Principle), with subprinciples of cultural, register and personal conformity, and examines its relationship to politeness.

2. Principles of conversation

2.1 The controversy regarding the principles of conversation

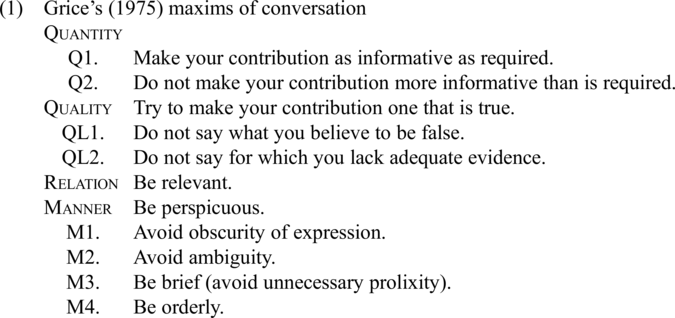

Echoing Kant’s (6Reference Kant2020[1818]: 107) four categories of possible judgement, which in turn are based on four of the Aristotelian categories, Grice (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975, Reference Grice1989: 26) refers to his conversational categories as quantity, quality, relation and manner, addressing them as maxims to speakers in the imperative, as illustrated in (1).

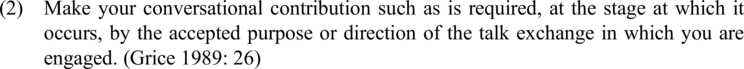

Grice (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975, Reference Grice1989) prefaces his four maxims with a ‘supreme conversational principle’ (Grice Reference Grice1989: 371), which he calls the cooperative principle (CP) and for which he also uses a formulation in the imperative directed at the speakers, as illustrated in (2).

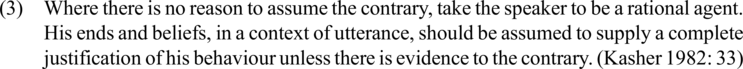

The CP has been criticised from various angles for its abstractedness (see, e.g., Kasher Reference Kasher and Kasher1976; Martinich Reference Martinich1980: 215; Grice Reference Grice1989: 368–371; Mooney Reference Mooney2004; Lindblom Reference Lindblom and Brown2006; Davies Reference Davies2007; Davis Reference Davis2010: 114–118), including the argument that instead of the ambiguous term ‘cooperation’, which has led to misinterpretations particularly in the transfer from philosophy to linguistics (see, e.g., Lindblom Reference Lindblom and Brown2006; Davies Reference Davies2007), ‘rationality’ would more accurately describe the underlying concept of conversational principles (see, e.g., Kasher Reference Kasher and Kasher1976: 210; Chapman Reference Chapman2005: 166–167; Davies Reference Davies2007). Kasher (Reference Kasher and Kasher1976: 210), who identifies the CP as ‘wrong and needless’, presents an alternative and apparent solution in terms of his rationalisation principle (RP) in (3).

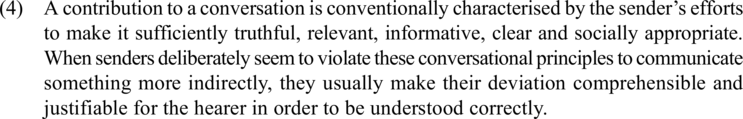

Although both CP and RP, as well as the maxims, aim to describe the norm of how interlocutors communicate – which is why some scholars (see, e.g., Chapman & Routledge Reference Chapman and Routledge2009: 86) refer to the principles more aptly simply as ‘the norms’ – they are each formulated in terms of a supposed guideline that unnecessarily obscures their actual relationship to conversational expectations in an old-fashioned Kantian manner. While the CP formulation sounds more like a guide for the speaker on how to communicate than like a description of how communication actually works, the RP reads like an instruction for the hearer on how to interpret the communicative behaviour of the speaker. However, Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975, Reference Grice1989) concept of cooperation refers primarily to the fact that speakers orient their contributions to the principles of conversation that form their common ground in order to be understood correctly by the other, and hearers therefore expect them to do so. Grice’s imperative formulation in the Kantian style, however, allows for a double use of the CP and therefore always carries with it the non-technical secondary meaning that the CP and the maxims can also serve to guide the speakers towards a supposedly more efficient, ideal communication.

In short, these maxims specify what participants have to do in order to converse in a maximally efficient, rational, co-operative way: they should speak sincerely, relevantly and clearly, while providing sufficient information. To this view of the nature of communication there is an immediate objection: the view may describe a philosopher’s paradise, but no one actually speaks like that the whole time! But Grice’s point is subtly different. It is not the case, he will readily admit, that people follow these guidelines to the letter. Rather, in most ordinary kinds of talk these principles are oriented to, such that when talk does not proceed according to their specifications, hearers assume that, contrary to appearances, the principles are nevertheless being adhered to at some deeper level. (Levinson Reference Levinson1983: 102)

The imperative tone of CP and maxims might misleadingly give the impression that maximally communicative efficiency depends on strict adherence to the principles. However, communicating something more indirectly via flouting the maxims is not necessarily associated with less efficiency than is a strict adherence to the principles. I argue that the cooperative nature of conversation in Grice’s technical sense and communication in a supposedly maximally efficient way (see Section 2.2.2) should be more strongly separated from each other and not combined in one and the same principle that suggests a causal relationship between the two. Maximal efficiency in communication is a more complex concept that can be defined differently, such as from a perspective of economy in the form of high information density (i.e. the use of fewer words with a high information content) or an individual perspective adapted to the personal needs of the hearer.Footnote 1 People often take deliberate detours by starting the conversation with ‘small talk’ instead of communicating what they want as directly as possible in order to build a better relationship between the interlocutors and achieve their respective subjective conversational goal in a socially appropriate way (see Sections 2.2.2 and 2.2.5). I therefore suggest that the formulation of the CP be clearly limited to the actual core objective, which is more of a description of how communication works than a guideline that includes a suggestion of how it should be, such as the formulation in (4).

By being subject to these conversational expectations contained with the principles, hearers look for explanations, reasons and motives for any apparent violations, as well as the (implicated) intended meanings associated with them. If the hearer does not realise that the speaker is deliberately violating common conversational principles, for example, by not recognising irony, an obscurely hidden meaning or the correct relationship between propositions, misunderstandings in communication are bound to occur. Speakers therefore often support inference drawing nonverbally, such as by rolling their eyes or smiling to support the inference of irony. The more accurately the hearer recognises the speaker’s (non-)adherence to the conversational principles, the more successfully the hearer can infer the intended meaning. This is what I will refer to as the Principle of Implicature Awareness (PIA). Implicature awareness refers to the current recognition of an implicated (intended) meaning, which of course does not require any scientific knowledge of the conversational system and occurs in the daily communication of interlocutors. The PIA relies on the causal relationship between the receiver’s awareness of the sender’s current (non-)compliance with conversational expectations and the resulting more successful understanding of the intended meanings. The PIA therefore states what follows in (5).

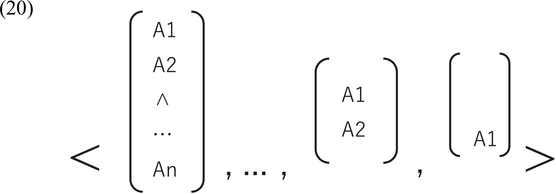

For example, the more aware the hearer is of the overtly communicated untruthfulness of the speaker’s expressed proposition, the easier it will be for them to recognise an intended ironic meaning. The hearer’s degree of awareness of the speaker’s currently implicated meaning is influenced by a variety of factors, including the cultural and (extra)linguistic context, individual prior knowledge, relationship with the speaker and experience with similarly implicated meanings and with the communicative behaviour of the corresponding speaker. These factors influence how attuned the hearer is to the (non-)observance of conversational principles and how accurately they can infer the intended meaning. While the PIA formulation in (5) refers to the hearer’s awareness of the speaker’s intended implicature, the speaker’s awareness of unintentionally triggered implicatures inferred by the hearer adds another layer to the general complexity of implicature awareness. The speaker might unintentionally convey a meaning they were not consciously aware of and may only recognise it later, as a presupposition derived from the hearer’s response. The hearer’s current implicature awareness, as they attempt to correctly infer the speaker’s intended meaning, is influenced by how overtly the violation is communicated. In cases of violating C1 or C3, this overtness is sometimes directed only at a particular hearer, in such a way that others (e.g. the children in examples 21 or 25) do not gain awareness of the deliberate violation of common conversational expectations and therefore cannot infer the intended implicature.

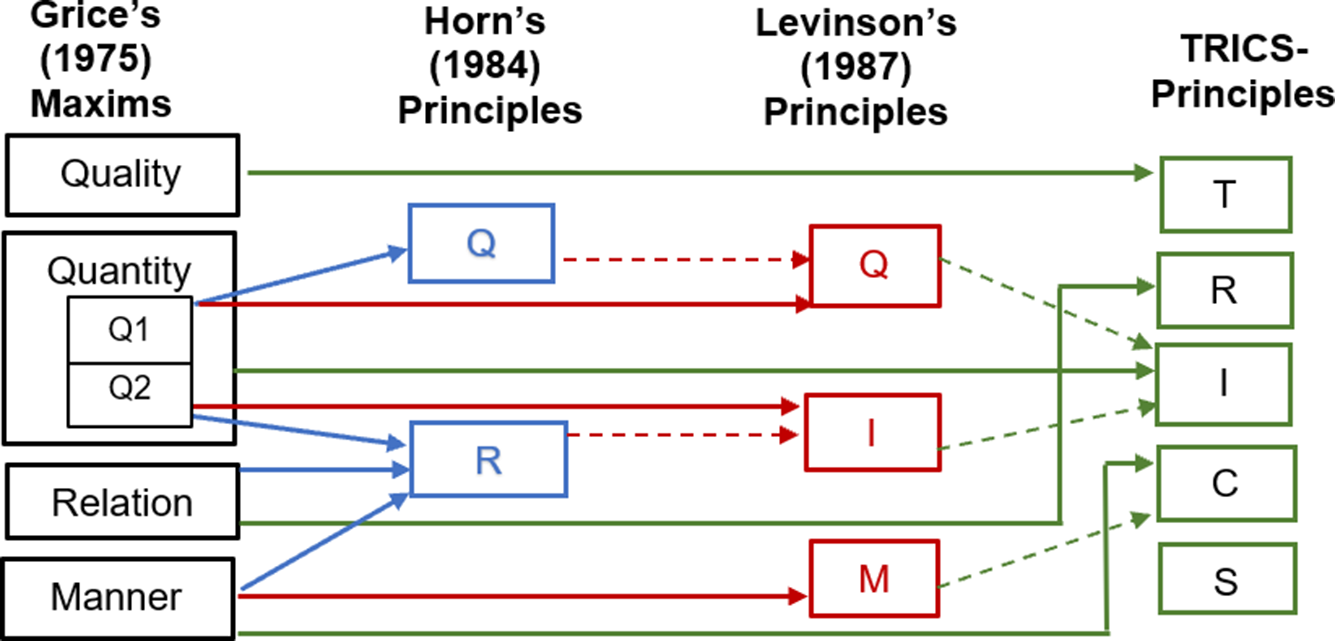

In addition to Grice’s imperative formulation of CP and maxims, there is a long-standing debate as to which maxims belong together, which can be subsumed under another, and which play a superior role. As mentioned in Section 1, Grice (Reference Grice1989: 371–372) questions the independence of the maxims from one another, particularly highlighting an interdependence between the maxims of relation and quantity and arguing that all maxims generally depend on the maxim of quality. Harnish (Reference Harnish, Bever, Katz and Langendoen1976: 362) and Leech (Reference Leech1983: 84–85) combine the maxims of quantity and quality; the former proposes the unifying maxim of quantity–quality: ‘Make the strongest relevant claim justifiable by your evidence’ (Harnish Reference Harnish, Bever, Katz and Langendoen1976: 362). By contrast, Horn (Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984) reduces the Gricean maxims to his two principles, R (subsuming Grice’s second quantity, relation and manner maxims) and Q (subsuming Grice’s first quantity maxim), leaving the maxim of quality as a given. Horn (Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006) then revises this subsumption slightly by positioning the first two manner submaxims under the Q-Principle. Levinson (Reference Levinson1987, Reference Levinson1991, Reference Levinson2000) provides three principles for generating generalised conversational implicatures (GCIs), the Q (subsuming Grice’s first quantity maxim), I (subsuming Grice’s second quantity maxim) and M (subsuming manner maxims) principles.Footnote 2 He leaves aside the Gricean maxims of quality and relevance, noting that the former ‘plays only a background role in the generation of GCIs’ (Levinson Reference Levinson2000: 74) and the latter ‘generates PCIs [i.e. particularised conversational implicatures], not GCIs’ (Levinson Reference Levinson2000: 74). In contrast, Sperber & Wilson (Reference Sperber and Wilson1995) propose an alternative approach based on a single cognitive principle of relevance (e.g. Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 198–199).

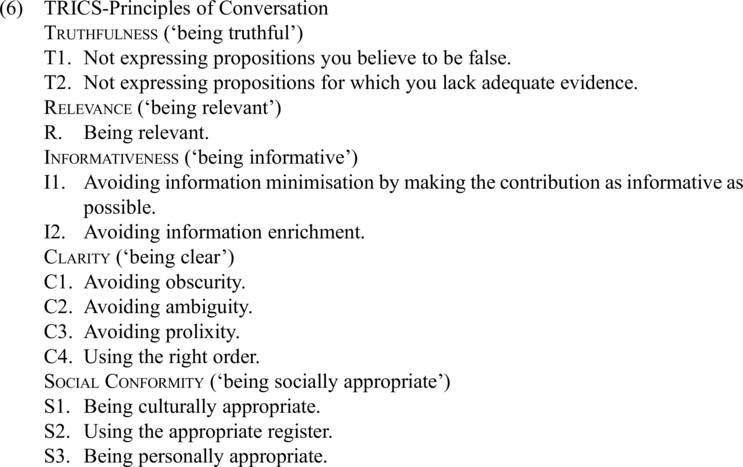

I agree with Levinson (Reference Levinson1989) that the complexity and diversity of inferences cannot be explained in their entirety by a single principle, such as Sperber & Wilson’s (Reference Sperber and Wilson1995) cognitive principle of relevance. However, I agree with them that relevance plays a fundamental and at the same time special role, not least in the hearer’s selection of the correct inference from the various possible implicated meanings. I argue that the different principle-based implicatures operate on different levels and that their alleged functional overlaps must be considered in a more differentiated way. For their classification, I provide a five-principle model that includes revised versions of Grice’s four principles, as well as a new principle of social conformity. I also change the broad and unapproachable names of the Gricean principles to truthfulness (for quality), informativeness (for quantity), relevance (for relation) and clarity (for manner), as these have been previously coined by numerous scholars (e.g. Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 584; Wilson & Sperber Reference Wilson and Sperber2002, Reference Wilson and Sperber2012), and abbreviate them collectively (i.e. together with the principle of social conformity) as the TRICS-Principles. This renaming not only achieves better content fit but also provides greater distance from Kant’s (6Reference Kant2020[1818]: 107) categories. Instead of Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) guideline formulation addressed to speakers in the imperative, I use a slightly revised formulation in terms of conversational expectations, as illustrated in (6).

The reasons for the concrete reformulation and extension of Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) principles in (6) are explained and demonstrated in more detail in the corresponding sections dedicated to the individual principles. Figure 1 provides an overview of how the TRICS-Principles relate to the principles proposed by Grice (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975), Horn (Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984) and Levinson (Reference Levinson1987).

Figure 1. Relation of the TRICS-Principles with the (neo-)Gricean approaches.

It is further widely assumed that the Gricean principles are associated with conversational expectations of varying priority (see, e.g., Grice Reference Grice1989: 27; Bach Reference Bach2001b: 19; Benton Reference Benton2016: 693–694).

It is obvious that the observance of some of these maxims is a matter of less urgency than is the observance of others; a man who has expressed himself with undue prolixity would, in general, be open to milder comment than would a man who has said something he believes to be false. (Grice Reference Grice1989: 27)

The following sections therefore also critically explore the extent to which the TRICS-Principles relate to conversational expectations of varying priority and illustrate various factors that contribute to shifts in this prioritisation.

2.2 The TRICS-Principles

2.2.1 Principle of truthfulness (T-Principle)

The status of Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) quality maxim as a principle in its own right is highly controversial (see, e.g., Grice Reference Grice1989: 27, 371; Wilson Reference Wilson1995; Horn Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006; Wilson & Sperber Reference Wilson and Sperber2002, Reference Wilson and Sperber2012: 49; Carston Reference Carston, Allan and Jaszczolt2012; Garmendia Reference Garmendia2018: 27). Although Grice (Reference Grice1989: 27) considers the observance of his first submaxim of quality to be a prerequisite for the operation of all the other maxims, he also acknowledges that it behaves similarly to the other maxims.

Indeed, it might be felt that the importance of at least the first maxim of Quality is such that it should not be included in a scheme of the kind I am constructing; other maxims come into operation only on the assumption that this maxim of Quality is satisfied. While this may be correct, so far as the generation of implicatures is concerned it seems to play a role not totally different from the other maxims, and it will be convenient, for the present at least, to treat it as a member of the list of maxims. (Grice Reference Grice1989: 27)

Grice (Reference Grice1989: 371) then shifts the focus of the maxim of quality more strongly to its function as a fundamental prerequisite by relating it to the speaker’s contribution as a whole (see, e.g., Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 197–198), rather than to what is literally expressed or ‘made as if to say’, introducing the latter as a way out of the assumed dilemma that one cannot ‘say’ (in the Gricean sense) something that is untrue.

The maxim of Quality, enjoining the provision of contributions which are genuine rather than spurious (truthful rather than mendacious), does not seem to be just one among a number of recipes for producing contributions; it seems rather to spell out the difference between something’s being, and (strictly speaking) failing to be, any kind of contribution at all. False information is not an inferior kind of information; it just is not information. (Grice Reference Grice1989: 371)

These seemingly contradictory assumptions have prompted various post- and neo-Gricean approaches to either omit this maxim entirely, such as Wilson & Sperber (Reference Wilson and Sperber2012: 49), or to limit it to its alleged role as a precondition for the successful functioning of the other maxims (see, e.g., Horn Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 7) instead of considering it to be a principle in its own right.

Following Grice himself – […] – many (e.g. Levinson 1983, Horn 1984a [i.e. Horn Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984 in my reference list]) have accorded a privileged status to Quality, since without the observation of Quality, or what Lewis (1969) calls the convention of truthfulness, it is hard to see how any of the other maxims can be satisfied (though see Sperber and Wilson 1986a for a dissenting view). (Horn Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 7)

This section defends the view of truthfulness as a conversational principle that can be overtly violated and whose violation does not necessarily preclude the effective operation of the other principles. It demonstrates the extent to which the other principles may operate under the umbrella of a flouted T-Principle, as well as factors influencing its widely assumed priority strength (see, e.g., Grice Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975, Reference Grice1989; Lewis Reference Lewis and Gunderson1975; Horn Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 7). Before illustrating its independent operation from the other principles, I address the controversy associated with Grice’s notion of ‘saying or making as if to say’ and the relationship between truth and truthfulness, providing an explanation of the proposed reformulation of the T-Principle in (6).

Following the T-Principle involves expressing what you believe to be true. Unlike the objectively verifiable concepts of truth and the truth conditions of semantics, the concept of truthfulness refers to the subjective ‘holding true’ of one’s own statement in a concrete context, which Lewis (Reference Lewis and Gunderson1975: 167) describes as avoiding uttering any sentences one believes to be false.

To be truthful in £ is to act in a certain way: to try never to utter any sentences of £ that are not true in £. Thus it is to avoid uttering any sentence of £ unless one believes it to be true in £. To be trusting in £ is to form beliefs in a certain way: to impute truthfulness in £ to others, and thus to tend to respond to another’s utterance of any sentence of £ by coming to believe that the uttered sentence is true in £. (Lewis Reference Lewis and Gunderson1975: 167)

Grice’s formulation of the supermaxim ‘Try to make your contribution one that is true.’ in (1) could misleadingly suggest a reference to objective truth, rather than the speaker-subjective truthfulness outlined in the first submaxim (see, e.g., Dynel Reference Dynel2018: 45). To avoid confusion between truth and truthfulness, I have reformulated Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) supermaxim in (6) as ‘being truthful’, understood as expressing a proposition the speaker believes to be true.

Another issue with the quality maxim is Grice’s ambiguous use of the notion of saying, which oscillates between a weaker and a stronger interpretation (see Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 202–203; Wilson & Sperber Reference Wilson and Sperber2002: 589–590). The weaker interpretation defines saying as ‘expressing a proposition, without any necessary commitment to its truth’ (Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 202). This aligns with the locutionary content in Austin’s (Reference Austin1962) sense (Korta & Perry Reference Korta, Perry and Tsohatzidis2007: 174) or the dictum as described by Partington (Reference Partington2007: 1557). By contrast, the stronger interpretation suggests that speakers necessarily commit themselves to the truth of the expressed proposition (Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 202–203; Wilson & Sperber Reference Wilson and Sperber2002: 589–590). Grice’s additional notion of ‘making as if to say’, particularly for cases like irony, suggests that he leaned towards the stronger interpretation. However, under this interpretation, instances like irony would not violate the maxim, as nothing is actually ‘said’ (see, e.g., Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 203; Wilson & Sperber Reference Wilson and Sperber2002: 590; Carston Reference Carston, Allan and Jaszczolt2012: 472; Garmendia Reference Garmendia2018: 2; Tamburini Reference Tamburini2023). Grice’s attempt to explain irony with this concept – alternatively addressed by Clark & Gerrig’s (Reference Clark and Gerrig1984) pretence theory and Sperber & Wilson’s (Reference Sperber and Wilson1995) echo account – has sparked a long-standing debate about the definition of what is said, with Recanati (Reference Recanati1989, Reference Recanati2001, Reference Recanati2004, Reference Recanati2010, Reference Recanati2017) and Bach (Reference Bach, Kenesei and Harnish2001a, Reference Bach2001b, Reference Bach and Szabó2005) offering opposing perspectives.

Although I align with Bach’s (Reference Bach, Kenesei and Harnish2001a: 149, Reference Bach2001b: 17, Reference Bach and Szabó2005: 25–26) interpretation of ‘saying’ in Austin’s locutionary sense, I deliberately avoid employing the ambiguous notion of ‘saying’ in my reformulation of the TRICS-Principles in (6) to account for differing views in this ongoing debate. In the context of a principle of truthfulness that can be overtly violated and accounts for a wide range of figurative language, my reformulation of the T-Principle is based on the weaker interpretation of saying, which involves expressing a proposition without necessarily committing to its truth. Consequently, I have revised Grice’s QL1 (‘Do not say what you believe to be false.’) and QL2 (‘Do not say for which you lack adequate evidence.’) as T1 (‘Not expressing propositions you believe to be false.’) and T2 (‘Not expressing propositions for which you lack adequate evidence.’), as outlined in (6).

The violation of the T-Principle (‘being truthful’) can either be overt (also known as flouting) or covert (see Grice Reference Grice1989: 30; Wilson & Sperber Reference Wilson and Sperber2012: 49–50). In both cases, speakers do not believe the proposition they are expressing to be true. In cases of covert violation, such as lying, speakers commit themselves to the truth of the proposition expressed, intending the hearer to believe it regardless (see, e.g., Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 200; Schaffer Reference Schaffer1982: 7). By contrast, in overt violations, such as the use of irony or metaphor, speakers do not commit themselves to the truth of the proposition expressed but instead implicate a different proposition, which may even – but does not necessarily – mean the opposite (see Grice Reference Grice1989: 34; Schaffer Reference Schaffer1982: 15; Giora Reference Giora1995: 241).

Depending on which of the two subprinciples is violated, the degree of expressed untruthfulness varies. When overtly violating QL1/T1, as in the case of irony, speakers express a proposition or literal content that they are certain is false. In contrast, when overtly violating QL2/T2, speakers typically express a proposition they believe is likely false. In both cases, speakers aim to make hearers recognise the untruthfulness of the proposition expressed, enabling them to infer the intended meaning. The hearer identifies the ‘contextual inappropriateness’ (Attardo Reference Attardo2000) of the literal meaning and derives the intended meaning. However, even in cases of verbal irony, Giora et al. (Reference Giora, Fein and Schwartz1998) empirically demonstrate that the initially processed literal meaning is neither replaced nor suppressed by the pragmatically inferred intended meaning, as the traditional suppression hypothesis suggests. Instead, the literal meaning remains activated to derive the ironical effect from the contrast between what is literally expressed and ‘what is referred to’ (Giora et al. Reference Giora, Fein and Schwartz1998: 96).

The type of the expressed untruthfulness varies not only between the subprinciples but also between different violations of the same subprinciple. Grice (Reference Grice1989: 34) provides the example of You are the cream in my coffee in a context where the metaphor is used ironically. The intended meaning of the first processed implicature through metaphorical use (p +> q) is then negated (p +> ¬q). In both metaphorical and ironical uses involving meaning inversion, the speaker does not believe the proposition expressed to be literally true, but with a difference in violating T1: in the case of metaphor, the speaker does not believe the proposition literally but rather believes that it ‘resembles (more or less fancifully)’ (Grice Reference Grice1989: 34) the intended meaning. In You are the cream in my coffee, for instance, the person addressed resembles the cream in the speaker’s coffee in certain ways, such as belonging to the speaker. Thus, the untruthfulness in metaphor often arises from its highly imaginative and literally unrealistic content, which is typically untrue in any conceivable world. The speaker does not expect the hearer to imagine that, in any world or context, the literal content of You are the cream in my coffee could be plausible. In contrast, when using irony, the speaker does not believe the literally expressed proposition to be true in the actual world but instead intends to contrast it with the implicated meaning, which, in Grice’s example above, is the inversed meaning.

In contrast to overtly violating T1, in which speakers express a proposition they certainly do not believe, in overtly violating T2, speakers express a proposition they believe to be probably false. Grice (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975: 53) illustrates an overt violation of T2 (henceforth referred to as AT2-based implicature, where AT2 means ‘Against T2’)Footnote 3 in the utterance in (7) in a given context in which the speaker has no reasonable reason to believe that this is the case.

In (7), the speaker does not believe that it is likely to be the case that ‘she’ is deceiving ‘him’. Instead, the speaker aims to convey that the person in question is prone to infidelity. By creating an imaginable world in which the literal content might be true, the speaker aims to implicate some believed true information, such as the tendency to be unfaithful.

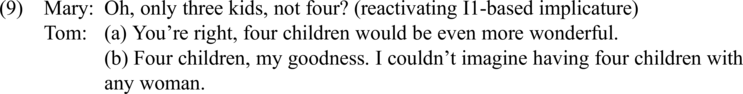

In contrast to Grice (Reference Grice1989: 27, 371) and several subsequent neo-Gricean accounts (see Horn Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 7), I defend the view that observing the T-Principle is not a necessary precondition for the effective operation of the other principles. Even when understood in its weaker interpretation – where the speaker expresses a proposition without necessarily committing to its truth – certain factors could still lead to the assumption that it plays a preconditional role, which I will now discuss in more detail. An implicature generated by overtly violating T1 (i.e. an AT1-based implicature) can easily dominate or overshadow I-, R- or C-Principle-based implicatures that occur simultaneously. An overt violation of the T-Principle has the capacity to influence other implicatures, even to the point of overriding them completely or rendering them seemingly irrelevant (‘irrelevant’ in the sense of less important, not to be confused with violating the R-Principle). In (8), the AT1-based implicature ‘not wanting kids from her’ is obviously more prominent than is the I1-based GCI ‘not four kids’, which does appear to be inactivated by the violation of the T-Principle.

However, the I-based implicature ‘not four kids’ is not invalidated but is only downgraded in prominence. Its prominence may easily be reactivated, as illustrated by Mary’s ironic query in (9), regardless of whether Tom’s subsequent answer continues to violate the T-Principle (a) or not (b).

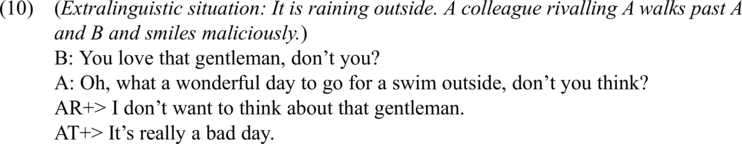

The operation of the R-, C- and S-Principles (Section 2.2.5) does not require the observance of the T-Principle either. Principles T and C can be successfully violated together in an ironic and simultaneously obscure conversation that aims to ensure that a third person does not understand what is actually being said. T- and R-Principles may also be felicitously violated together, as (10) illustrates.

The change of topic in the irony-based conversation in (10), where the rainy weather clearly contradicts the suggestion of swimming outside, generates the same AR-based implicature that a non-ironic conversation does. This shows that an irony-based conversation – or, more generally, a violation of the T-Principle – does not necessarily diminish expectations of relevance. On the contrary, the additional violation of the R-Principle is perceived as being more prominent than is the previous, habitual and expected violation of a principle. This is due to what I will call the ‘habituation effect of principle violations’ (HEP), which occurs when the same principle is violated repeatedly and the hearer is already habituated to this kind of violation. Due to the HEP, expectations of compliance with a principle that has been repeatedly violated become lower and lower, and the unexpected violation of a principle is consequently weighted more heavily. For example, in an ongoing conversation based on irony, expectations of truth increasingly diminish due to the HEP, while other conversational expectations remain intact and their unexpected violation inevitably becomes more salient, as in the case of R-Principle violations.

While the HEP illustrates that repeated violations of certain conversational principles (such as the T-Principle in irony-based conversations) lead to a diminishing expectation of adherence, this habituation should not be considered in isolation. Rather, it is strongly influenced by the expectations of the hearers, which are shaped by their schematic knowledge and the specific context of the interaction (see, e.g., Levinson Reference Levinson1979; Mooney Reference Mooney2004). According to Levinson’s (Reference Levinson1979) concept of ‘activity types’, communicative contexts create different horizons of expectation, which result in varying weightings of principle violations. A violation of the T-Principle in an informal conversation may be accepted more quickly than in a formal meeting, where the expectations of truth and relevance are stricter. At the same time, the R-Principle remains intact even in irony-based conversations, and its violation can stand out more prominently in such a context.

2.2.2 Principle of relevance (R-Principle)

Grice’s maxim of relation (‘be relevant’), which is often referred to as the maxim of relevance, is highly controversial in terms of its definition, its independence from other principles and its special role in conversation. While Horn (Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006) partially follows Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) assumed interdependence between Q and R, subsuming Q2 and R under his R-Principle (see Section 2.2.3), Levinson (Reference Levinson1987: 401, Reference Levinson2000) strictly distinguishes between a PCI-generating principle of relevance and GCI-generating principles based on informativeness and clarity. In contrast, Sperber & Wilson’s approach (Reference Sperber and Wilson1995) replaces the Gricean framework – or at least the maxims of quantity, relation and manner, given the justified omission of truthfulness – with a single principle of relevance (see, e.g., Wilson Reference Wilson1995: 198–199).Footnote 4 While Lewis (Reference Lewis and Gunderson1975: 31) assumes relevance as a by-product of his convention of truthfulness, Wilson & Sperber (Reference Wilson and Sperber2002: 584) propose an inverse relationship between the two principles.

However, Lewis does not explain how regularities of relevance might be by-products of a convention of truthfulness. One of our aims will be to show that, on the contrary, expectations of truthfulness—to the extent that they exist—are a by-product of expectations of relevance. (Wilson & Sperber Reference Wilson and Sperber2002: 584)

Keeping a strong focus on principles that generate conversational implicatures (including both GCIs and PCIs), I argue that neither truthfulness nor relevance is a by-product of the other principle. Expectations of truthfulness and relevance are fundamental expectations in conversation, but the two principles operate independently of each other in that a contribution may be untruthful and relevant, or untruthful and lacking in relevance, as I have shown in Section 2.2.1. The R-Principle operates on a completely different level than do the other principles in that the interlocutors try to make connections between the uttered and the (linguistic and extralinguistic) context regardless of whether the other principles are violated.Footnote 5

The R-Principle is the most difficult concept to define without establishing an apparently circular theory. Unlike the T-, I-, C- and S-Principles, which are based on objectively verifiable criteria, the notion of relevance is highly ambiguous and is inevitably associated with the subjective evaluation of what a person considers to be important. However, what is considered to be important can be interpreted differently by a sender and a receiver and cannot be considered to be an objectifiable principle of a successful conversation. The objective notion of relevance is linked to a relationship or connectedness between two elements in many scientific disciplines; for example, in the field of law,Footnote 6 it refers to the relationship between an item of evidence and a fact. In conversation, it can be linked to the relationship between propositions (such as within two conjuncts or sentences). Echoing Kant (6Reference Kant2020[1818]: 107), Grice (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975, Reference Grice1989: 27) places his maxim of ‘being relevant’ under the category of relation. However, Grice (Reference Grice1989: 27) notes that it is a seemingly more complex concept than he can fully capture at the time of writing.

Under the category of Relation I place a single maxim, namely, ‘Be relevant.’ Though the maxim itself is terse, its formulation conceals a number of problems that exercise me a good deal: questions about what different kinds and focuses of relevance there may be, how these shift in the course of a talk exchange, how to allow for the fact that subjects of conversation are legitimately changed, and so on. I find the treatment of such questions exceedingly difficult, and I hope to revert to them in later work. (Grice Reference Grice1989: 27)

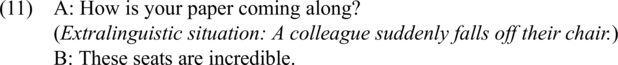

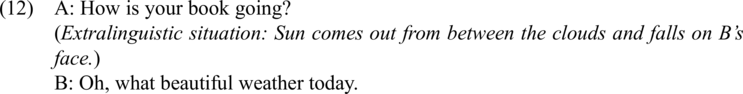

The questions of legitimately changing the subjects of conversation, which Grice (Reference Grice1989: 27) finds exceedingly difficult, are the ones I will now address. In contrast to Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) original maxim of relation, I argue that following the R-Principle does not necessarily mean that an assertion must relate to the current topic of conversation; it can also relate to the extralinguistic situation, as illustrated in (11) and (12).

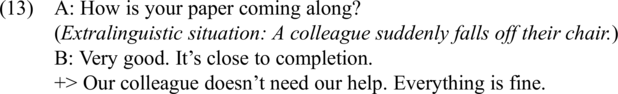

Without the given extralinguistic situation, B’s answers to A’s questions in (11) and (12) would be considered violations of the R-Principle. However, B’s answer follows the R-Principle by legitimately changing the topic of conversation due to the extralinguistic situation in the interlocutors’ physical environment. After this legitimate change of subject due to an extralinguistic distraction, B can return to the question and answer it without having implicated anything based on a violation of the R-Principle. In some cases, not responding to or ignoring such extralinguistic activity, to which one would usually expect a response, could even be regarded as a violation of the R-Principle in a specific context situation, as illustrated in (13).

Thus, to account for the legitimate change in the topic of conversation, we must also consider the speaker’s assertion in the context of the given extralinguistic situation. The hearer intuitively distinguishes between apparently unfounded topic changes and those that appear to be justified because they have been caused by external influences. Therefore, Leech’s (Reference Leech1983: 94) definition, which limits the relevance principle exclusively to the conversational goals of the speaker or hearer, is overly restrictive. In his later work, Leech (Reference Leech2014: 317) broadens this definition by removing the term ‘conversational’, allowing it to encompass additional goals, such as social objectives.

An utterance U is relevant to a speech situation if U can be interpreted as contributing to the conversational goal(s) of s or h. (Leech Reference Leech1983: 94)

[A]n utterance is relevant to the extent that it can be recognized as contributing to the goals of the speaker (or hearer). (Leech Reference Leech2014: 317)

I argue that the R-Principle should be expanded further to incorporate an extralinguistic component. This adjustment would account for factors that may arise unexpectedly and independently of the speaker’s intentions, thereby enabling the speaker to address them without violating the R-Principle. In searching for relevance, the hearer relates the speaker’s proposition to the linguistic or extralinguistic environment. The extralinguistic environment encompasses the physical surroundings as well as the individual and mutual cognitive environments (for a discussion of ‘cognitive environment’, see Sperber & Wilson Reference Sperber and Wilson1995). The linguistic environment includes not only the preceding co-text provided by the interlocutors but also any assertions present in the physical environment that are available to both the speaker and hearer. To distinguish a legitimate topic change as a reaction to an extralinguistic distraction from a topic change deliberately employed by the speaker to create an R-based implicature, hearers often have to pay attention to additional, supporting cues, such as tone of voice, facial expression, or gestures. These nonverbal cues help the hearer discern whether the speaker is intentionally using the extralinguistic event as a diversion from the previous topic – implicating, for instance, discomfort with the subject – or merely reacting spontaneously to the distraction.

Moreover, conversations are not always directed towards achieving a specific conversational goal, as speakers often take deliberate detours. As Blakemore observes, ‘[e]ven if a communicator has the most relevant information, he may be prevented from communicating it by other considerations (for example, tact, politeness, the law)’ (Blakemore Reference Blakemore2009: 62). Human conversation is more complex than merely focusing on one specific goal or maximally efficient information exchange. Unlike current artificial intelligences, human speakers integrate personal information about their interlocutors, details about the environments they perceive, and insights into the rules of social conformity (see Section 2.2.5) when choosing their words. They deliberately engage in conversational detours, such as ‘small talk’, even when their more urgent communication goal is entirely different. For instance, imagine person A needing specific information from person B. However, A refrains from directly addressing their concern (i.e. A does not establish a connection to their most urgent concern) and instead begins with ‘small talk’ about the weather or by asking about B’s well-being, before transitioning to the actual, more relevant question related to their concern. In some cases, it is precisely this detour that becomes the most effective way of communicating to obtain the needed information in the end.

Interlocutors strive to establish a felicitous relationship even between propositions that violate one or more of the I-, C- and T-Principles. Thus, violations of the other principles do not diminish the hearer’s expectations of relevance. Although speakers and hearers can differentiate and select between more relevant and less relevant (i.e. more and less connected) assertions and implicatures, the graduality of relevance (i.e. the degree of connectedness) – in opposition to the graduality of informativeness – has no significant influence on the generation of implicatures. While informationally enriched, under-informative and even exactly informative contributions logically generate implicatures through lower and upper bounds, a contribution that is still connected (i.e. relevant) to the (non-)linguistic environment but less relevant than another alternative contribution does not necessarily risk violating the R-Principle. Instead, the implicature typically – but does not necessarily, as I have demonstrated – arises by deliberately disconnecting from a current topic. I therefore argue that a violation of the R-Principle occurs on a completely different level than does a violation of the I-Principle. This independent operation of the R- and I-Principles will be demonstrated in more detail in Section 2.2.3.

2.2.3 Principle of informativeness (I-Principle)

The I-Principle (‘being informative’) is based on Grice’s maxim of quantity, which is controversial in terms of its division into different subprinciples, its (in)dependence and its connection to the other maxims (see, e.g., Grice Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975: 47, Reference Grice1989: 372; Levinson Reference Levinson1987: 401; Horn Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984, Reference Horn, Shore and Vilkuna1993, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 14; Carston Reference Carston1995). While I have demonstrated its independence from the T-Principle in Section 2.2.1 and will show its independence from the C-Principle in Section 2.2.4, in this section, I demonstrate its independence from the R-Principle.

The precise relationship between the principles of informativeness and relevance is highly controversial. Grice (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975, Reference Grice1989: 372) assumes an interdependence between the two principles.

The operation of the principle of relevance, while no doubt underlying one aspect of conversational propriety, so far as implicature is concerned has already been suggested to be dubiously independent of the maxim of Quantity. (Grice Reference Grice1989: 372, emphasis added)

(The second maxim [i.e. of Quantity] is disputable; it might be said that to be overinformative is not a transgression of the CP [i.e. Cooperative Principle] but merely a waste of time. […] However this may be, there is perhaps a different reason for doubt about the admission of this second maxim, namely, that its effect will be secured by a later maxim, which concerns relevance.) (Grice Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975: 46, Reference Grice1989: 26–27)

Horn (Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 14) aptly notes that ‘Grice himself incorporates R in defining the primary Q maxim (“Make your contribution as informative as is required”)’ (Horn Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 14, emphasis added by Horn). In turn, Horn assumes that Q2 incorporates R, stating: ‘what could make a contribution more informative than required, except the inclusion of contextually irrelevant material?’ (Horn Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 14). Therefore, Horn (Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984) subsumes the Q2 maxim together with the relevance and manner maxims under his R-Principle before later modifying this subsumption slightly by including the manner maxims M1 and M2 under the Q-Principle (see, e.g., Horn Reference Horn, Shore and Vilkuna1993, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006).Footnote 7 Although Horn (Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006: 14) refers to Martinich (Reference Martinich1980) regarding the alleged interdependence, the latter also demonstrates that ‘many over-informative conversational contributions are nonetheless relevant contributions’ (Martinich Reference Martinich1980: 218). Levinson (Reference Levinson1987: 401) explicitly contradicts an interdependence of the two principles.

Both Horn and Sperber & Wilson independently identify this principle [i.e. Quantity 2] with Relevance (for the reasons that Grice hinted), but this is, I believe, mistaken, for (pretheoretically, anyway) relevance is not primarily about information – relevance is a measure of timely helpfulness with respect to interactional goals. (Levinson Reference Levinson1987: 401)

I argue that the assumption of an alleged interdependence between Q2 and R is caused not least by the infelicitous formulation of ‘is required’, which is used circularly in Q2 ‘Do not make your contribution more informative than is required’ (Grice Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975: 45, emphasis added). To avoid confusion between Q2 and R, my revised I-Principle omits circular phrases that might suggest dependency on relevance, such as ‘as is required’ or ‘as is necessary’. By removing the circular dependency on relevance, the I-Principle establishes informativeness as an independent concept that generates implicatures based solely on the information provided, without necessarily relying on relevance. As illustrated in (6), I reformulate Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) first quantity maxim (Q1) ‘Make your contribution as informative as required’ with ‘Avoiding information minimisation by making the contribution as informative as possible’ (I1) and his second quantity maxim (Q2) ‘Do not make your contribution more informative than required’ (Q2) with ‘Avoiding information enrichment’ (I2). Instead of dividing the quantity maxim into two different principles in the manner of Horn (Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006) and Levinson (Reference Levinson1987, Reference Levinson1991), I preserve the Gricean subsumption of Q1 and Q2 (as I1 and I2, respectively) under the I-Principle and incorporate their oppositive interplay, shown and advanced particularly by Horn (Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984), into their wording. Although the I-Principle is reformulated without the formulation ‘as required’ or ‘than required’, which suggest relevance dependency, its observance or violation nevertheless generates the same implicatures originally described by Grice (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975). Following I1, for example, means that the speaker avoids saying that they have two children if it is also true that they have three. Because the hearer, in accordance with the I-Principle, assumes that the speaker’s contribution is maximally informative and therefore excludes via a GCI that more information holds than the speaker has asserted. Thus, based on the speaker’s assertion of ‘having two children’, the hearer infers ‘not more than two children’ by default. I call I1-based implicatures, which limit the information by exclusivity and thus exclude more information than is asserted (Grice Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975; Horn Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984; Levinson Reference Levinson2000), L-implicatures (L stands for ‘information-limiting’; L+> for ‘L-implicates’). The most frequently discussed type of L-implicatures are scalar implicatures, which arise when a weaker statement W implicates the negation of a stronger assertion S (W+> ¬S) (Horn Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006; Levinson Reference Levinson2000), as illustrated in (14).

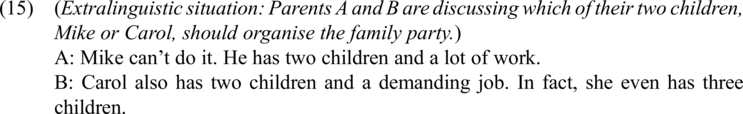

However, a violation of I1 through information minimisation should not necessarily be associated with irrelevance. A contribution can be informationally minimised but still relevant (i.e. not violating the R-Principle), as B’s response in (15) demonstrates by saying ‘two children’ instead of ‘three’ at first.

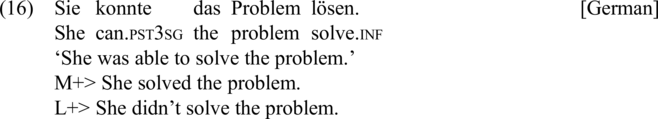

The same holds for implicatures that arise from violating the I2 maxim (‘Avoiding information enrichment’) by giving more information than is asserted, which I refer to as M-implicatures (M stands for ‘more information’; M+> for ‘M-implicates’). As opposed to scalar implicatures, in which a weaker statement implicates the negation of a stronger statement (W+> ¬S) on the scale <S, W>, M-implicatures include those in which a weaker statement implicates the stronger statement (W +> S). In considering modality as a scalar item on a scale <S, W>, where the modalised assertion represents the factually weaker version ‘W’ of a factually stronger, non-modalised assertion ‘S’, a modalised assertion – such as the German example in (16) Sie konnte das Problem lösen (‘She was able to solve the problem’) – may M-implicate a stronger, non-modalised proposition, such as ‘She solved the problem’ (Horn Reference Horn1972, Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006; Atlas & Levinson Reference Atlas, Levinson and Cole1981; Levinson Reference Levinson1983, Reference Levinson1987, Reference Levinson2000; Verstraete Reference Verstraete2005; Ziegeler Reference Ziegeler2006). Without additional context, the M-implicature of ‘solving’ in (16) is more prominent than the L-implicature of ‘not solving’.Footnote 8

Because the hearer expects a truthful and relevant contribution, they retrieve the most likely of all possible contextual situations to which the utterance in (16) might relate. The hearer expects the stronger M-implicated statement of ‘solving’ to be more likely precisely because it appears to be more relevant (to the zero context) than does ‘only having had the ability in the past and ultimately not having done it’. The latter would require more context to become relevant, including a reason why ‘she’ ultimately did not solve the problem.

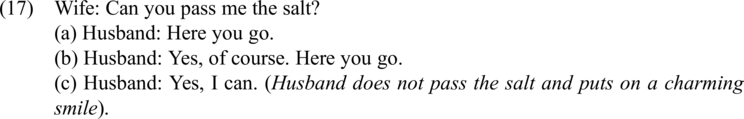

Similarly, I consider the long-disputedFootnote 9 intended meaning of ‘Can you pass me the salt?’ in (17) as an M-implicature of the type ‘Can/could you do X?’ M+> (‘Would you please do X?’+> Do you please do X? +>) ‘Do X, please’.

Whereas the husband’s response in (a) addresses the intended M-implicated meaning of passing the salt directly, responses (b) and (c) also address the meant (b) and literal (c) questions without being redundant. Instead of answering the meant question ‘Would you please pass me the salt?’, as in (b), the husband in (c) violates the R-Principle by answering the literal, non-intended and less relevant L-implicated question, which merely concerns his ability to pass the salt.

Leech (Reference Leech2014: 304–320) provides a Searle-Gricean account and argues that indirect speech acts like (17) violate all four of Grice’s maxims to some extent, such as truthfulness by ‘“pretending” that H [i.e. the hearer] may or may not be able to perform the action’ (Leech Reference Leech2014: 318), clarity by being unnecessarily obscure, and relevance by being less directly related to the situation than direct speech acts. However, I argue that the intended meaning of the request to pass the salt is not derived from untruthfulness, prolixity or a shift to an unrelated topic. Instead, there is a clear relation between asking for the ability to pass the salt and the request to do so, even if the speaker has already assessed the hearer’s ability based on local proximity. It can be seen as expressing a potentially redundant (i.e. in the sense of not necessary, not in the sense of being disconnected, and therefore, as I argue, not to be confused with a violation of the R-Principle) precondition step, depending on the situation (e.g. how far the hearer is sitting from the salt), via an indirect speech act. The conventionalised indirect request is essentially a shortened version of an anticipated dialogue, such as: ‘A: Can you do X? B: Yes, I can. A: Will you then do X (+> for me)? B: Yes, I will (and does it).’ I consider the intended meaning of ‘Can/could you do X?’ M+> (‘Would you please do X?’+> ‘Do you please do X?’ +>) ‘Do X, please’ to be an implicature of enrichment (i.e. a violation of I2), where the modalised weaker version M-implicates the non-modalised stronger request. This example also illustrates that a violation of I2 and adherence to the R-Principle (i.e. being over-informative and relevant at the same time) are not mutually exclusive (see discussion above), and that the principles of R and I are not interdependent.

Apart from I-based implicatures, which can be clearly derived from the scale <S, W>, L-implicatures of the type in (18) and (19) require a special discussion regarding whether and how they can be ranked in terms of weaker and stronger values.

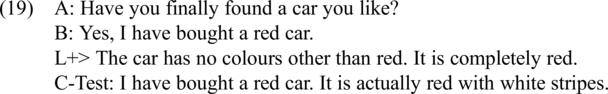

According to Levinson (Reference Levinson2000: 115), higher specificity is correlated with higher informativeness. Higher informativeness here is not to be confused with M-implicating more information than is asserted and rather refers to asserting more information (e.g. by having more specific features) than would an alternative weaker element with less (specific) features. In considering specificity on the scale <S, W>, the non-specificity given in example (18) L-implicates (W+> ¬S) the negation of specificity by default: [-specific] +> ¬[+specific]. By contrast, asserting a specific item – such as the specific colour ‘red’ of the car in (19) – L-implicates a limitation to that specific hyponym, thus pragmatically excluding that more co-hyponymic related hyponyms additionally apply than is asserted. In (19), the hearer infers that the car has no more colours than the one asserted. If A1 and A2 represent different hyponyms (such as ‘blue’, ‘red’ and ‘yellow’) of the same hypernym A (‘colour’), the implicature can be formulated as follows: A1+> ¬(A1∧A2,3,4…n). In considering stronger specificity or the presence of a greater number of features or hyponyms to be a stronger value than lower specificity or the absence of features, the pragmatic scale <S, W> can be applied as illustrated in (20).

2.2.4 Principle of clarity (C-Principle)

The C-Principle is based on Grice’s (Reference Grice, Cole and Morgan1975) maxim of manner, which includes avoiding obscurity, ambiguity, prolixity, and using the correct order. Grice believes that ‘its potentialities as a generator of implicature seem to be somewhat open to question’ (Grice Reference Grice1989: 372). Compared to the other principles, little attention was paid to the C-Principle (see, e.g., Rett Reference Rett2020) and expectations of observing it tend to be of lower priority (Grice Reference Grice1989: 27). The manner submaxims are particularly controversial regarding their subsumption under or interdependence with other principles (see, e.g., Horn Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984, Reference Horn, Shore and Vilkuna1993, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006; Levinson Reference Levinson2000). Horn (Reference Horn, Shore and Vilkuna1993, Reference Horn, Horn and Ward2006) also revises his initial subsumption of the four manner maxims under his R-Principle (see Horn Reference Horn and Schiffrin1984, Figure 1) by including the manner maxims M1 and M2 under his Q-Principle, leaving M3 and M4 under his R-Principle. To verify my assumption that an overt violation of the clarity subprinciples does not necessarily correlate with a violation of my R- and I-Principles, I provide examples of each subprinciple, C1–C4.

First, a violation of C1 via obscurity is not necessarily accompanied by a violation of the other principles, as the truthful, relevant and informative yet obscure contribution in (21) illustrates.

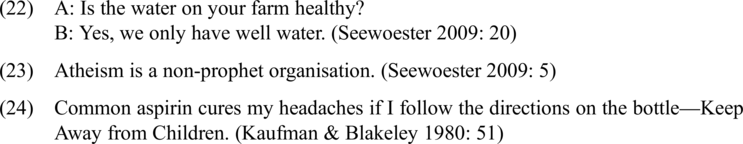

Second, a truthful, relevant or informative contribution may be intentionally ambiguous. The C2-violating examples in (22), (23) and (24) show the different possibilities of (non-)compliance with the other principles. In contrast to (22), in which only one of the two meanings is true, (23) is true in both meanings and could be uttered in a certain context to highlight a contrast with a for-profit organisation. In (22) and (23), each of the two meanings is relevant to the context. In (24), however, the speaker plays with the ambiguity of ‘Keep [the aspirin/myself] away from children’, allowing for two interpretations. The first meaning, a standard safety warning, suggests keeping the aspirin away from children, while the second interpretation humorously suggests that the speaker should keep themselves away from children to avoid headaches. This intentional ambiguity violates C2 by introducing two conflicting interpretations. Despite this, only the second interpretation (i.e. ‘Keep myself away…’) establishes a semantically/pragmatically acceptable connection with the preceding proposition (i.e. is relevant).

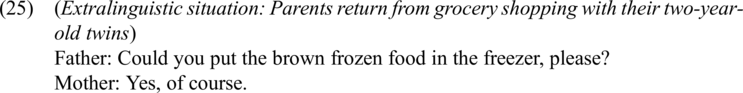

Third, a C3 violation caused by prolixity should not be confused with being over-informative – that is, violating I2. While being over-informative in the sense of the enrichment caused by violating I2 means that a person implicates more information than they assert, being intentionally prolix refers to a person intentionally asserting more (for example, by using more words) than they need or would usually do to convey the intended information. Furthermore, a prolix contribution is not necessarily disconnected from the (extra)linguistic situation, inducing an AR-based implicature. In (25), the use of ‘brown frozen food’ for ‘ice cream’ is highly related (i.e. relevant) to the situation in front of the children.

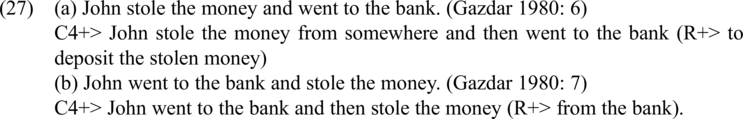

Fourth, observance of the last subprinciple C4 means that ‘if certain items or events have a spatial, temporal or causal order, then in describing those items or events one should reproduce that order in the sequence of one’s description’ (Gazdar Reference Gazdar1980: 6). Typical I4-based examples include (26) and (27).

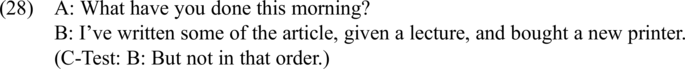

In (26), the correct order is strongly assumed because it would not only be against the conventional order for a person to go to bed and then brush their teeth, but it would also be excluded from the definition of ‘going to bed’, which indicates that people do not get up afterwards to engage in another activity. In (27), the correct order is urgently needed not only to infer the correct temporal order but also to subsequently identify the correct relationship between the two conjuncts. The hearer is forced by expectations of relevance – not by the C4-subprinciple, as is widely believed – to link the two conjuncts semantically/pragmatically and to identify the most relevant relationship between them. Thus, using the incorrect order may mislead the hearer and cause them to make false assumptions about the relationship between the two propositions. However, violating the C4-subprinciple does not necessarily correlate with irrelevance. In (28), the hearer’s expectations of the correct order are considerably lower and less urgent than they are in (26) or (27), but they can still be present, as shown by the fact that a subsequent statement such as ‘But not in that order’ does not appear redundant when uttered by B.

B’s answer remains relevant to A’s question in (28), even if the order is incorrect; for example, the printer may have been ordered before the lecture was given, and/or the article might have been written after ordering the printer. Regardless of whether C4 has been violated or not, B’s response remains truthful, informative, socially appropriate and relevant to A’s question. Thus, the C-Principle also operates independently of the other principles.

2.2.5 Principle of social conformity (S-Principle)

Grice acknowledges that his conversational model does not yet cover all possible conversational implicatures and needs to be extended to include further maxims ‘such as “Be polite”’ (Grice Reference Grice1989: 28). However, since Lakoff’s (Reference Lakoff, Corum, Smith-Stark and Weiser1973) and Leech’s (Reference Leech1983, Reference Leech2014) proposals for a principle of politeness,Footnote 10 the status of linguistic politeness (LP) as a principle in its own right has been contested (for overviews from different perspectives, see, e.g., Terkourafi Reference Terkourafi2005; Brown Reference Brown and Wright2015a, Reference Brown and Huang2015b). While some scholars argue for a principle of politeness within an integrative conversation model (e.g. Lakoff Reference Lakoff, Corum, Smith-Stark and Weiser1973; Leech Reference Leech1983; Kingwell Reference Kingwell1993; Kallia Reference Kallia2004, Reference Kallia2007; Pfister Reference Pfister2010; Leech Reference Leech2014; Okanda et al. Reference Okanda, Asada, Moriguchi and Itakura2015; Asada et al. Reference Asada, Itakura, Okanda, Moriguchi, Yokawa, Kumagaya, Konishi and Konishi2022), others view LP as detached from Gricean principles (e.g. Brown & Levinson Reference Brown and Levinson1987; Culpeper Reference Culpeper1996; Brown Reference Brown and Wright2015a, Reference Brown and Huang2015b; Haugh Reference Haugh2007, Reference Haugh2015; Jucker Reference Jucker2020; Culpeper & Haugh Reference Culpeper, Haugh, Haugh, Kádár and Terkourafi2021).

Although certain rules of LP have an objective claim in a linguistic community or within a social group, LP is also subject to the individual perception of the person being addressed. An utterance intended as polite by the speaker can also appear as impolite to the hearer. Brown & Levinson (Reference Brown and Levinson1987: 15) show that sociological factors, such as the ‘relative power’ of the hearer over the speaker and vice versa, the ‘social distance’ between them and the ‘ranking of the imposition’ of the face-threatening act involved, play a crucial role in determining the degree of politeness. I therefore agree with Brown & Levinson (Reference Brown and Levinson1987: 5), Brown (Reference Brown and Wright2015a, Reference Brown and Huang2015b), Culpeper (Reference Culpeper1996), Haugh (Reference Haugh2007, Reference Haugh2015: 142), Jucker (Reference Jucker2020) and Culpeper & Haugh (Reference Culpeper, Haugh, Haugh, Kádár and Terkourafi2021), amongst others, that LP requires a more complex theory detached from conversational principles that generate calculable implicatures.

Violating one or more of the TRICS-Principles (such as deliberately changing the topic of conversation or talking obscurely about a third person who is present in order to exclude them from the conversation) may be perceived as impolite by hearers in some cases, or as polite in others. Irony can serve as ‘a politeness strategy’ (Leech Reference Leech1983; Brown & Levinson Reference Brown and Levinson1987; Giora Reference Giora1995), such as when using ‘Thank you’ instead of the more aggressive ‘Damn you!’ (Giora Reference Giora1995: 260). However, irony can also be used impolitely to make fun of someone in a particular context, supported by a correspondingly derogatory intonation.

(Im)politeness also often arises as a by-product via the (non-)observance of a principle that I refer to as the principle of social conformity (S-Principle), without the two being directly correlated. Observing the S-Principle of conversation means that humans constantly adapt their assertions to their social environment.Footnote 11 This includes, at the least, making the contribution culturally appropriate (S1), register appropriate (S2) and personally appropriate (S3).Footnote 12 A violation of cultural conventions (S1) may generate various implicatures (PCIs) of culture-specific backgrounds. This includes cultural expectations of different social groups both between and within linguistic communities. For example, people living in the German cities of Düsseldorf and Cologne, which are linked by a long history of rivalry, follow different cultural conventions regarding drinking beer and carnival celebrations. Ordering a type of beer in Cologne that is conventionally drunk in Düsseldorf, or vice versa, may well lead to conversational responses implicating rejection, as illustrated in (29).

Whereas the guest’s order would be highly culture-adjusted in Düsseldorf, it is culturally expected to order a Kölsch beer in Cologne, particularly in a traditional brewery pub. Thus, the guest, knowingly or unknowingly, violates the waiter’s cultural expectations by ordering the culturally rival beer. The waiter’s typical answer, following S1, implicates his culturally determined (i.e. appropriate and highly expected within this culture) rejectionFootnote 13 of this type of beer by comparing it to a bouillon cube dissolved in a glass of water. Although the waiter’s answer might give the guest the subjective impression of impoliteness or rudeness as a possible by-product (especially if the guest is unfamiliar with this type of cultural game), the S-based implicature is not inherently linked to impoliteness or rudeness. Guest and waiter may also deliberately engage in this cultural game in a friendly and even polite manner, perhaps supported by a friendly, provocative smile. Thus, the (non-)observance of the S-Principle does not necessarily correlate with (im)politeness.

Furthermore, S-based implicatures should not be confused with C-based implicatures, which arise from how something is expressed, such as the deliberate choice of a more elaborate phrasing to convey a subtly veiled meaning. While a response like ‘We don’t serve X (e.g. orange juice), but I can offer you Y (e.g. an effervescent tablet dissolved in a glass of water) as an alternative’ would ordinarily be a straightforward response from a waiter if taken at face value, in this context, the waiter makes this unusual offer based on specific cultural conventions associated with local rivalry, compelling him to clarify his stance. The intended meaning here is not generated by a deliberate use of prolixity or ambiguity but rather by shared cultural expectations that hearers familiar with these conventions would recognise. S1-based implicatures rely on shared cultural understanding to convey a specific meaning, independently of the phrasing strategies that give rise to C-based implicatures. The more precisely hearers understand what is culturally appropriate to communicate, the easier it is for them to infer the intended meaning of S1-based implicatures.

Following S2 means adapting a contribution to the conventional rules in the appropriate register. The husband’s amusing response in (30) intentionally violates the conventional register of a couple sitting on the sofa by choosing a more genteel and distanced register that belongs to the more upmarket gastronomic sector.

By using a typical waiter–guest register, the husband could implicate that his wife has become too comfortable and requires too much pampering. However, he could also simply want to communicate that he would do anything for her on this particular evening in a charming way. To ensure that his wife draws the correct inference, he might communicate this with the support of appropriate facial expressions, gestures and intonation. While the inference generated by the violation of S2 in (30) might lead to a certain impression of (im)politeness, S2-based implicatures, like those based on S1, are not necessarily linked to any specific form of (im)politeness.

The husband’s response in (30) also flouts S3 because his contribution can be considered as personally inappropriate (‘madam’) in relation to the wife being addressed. Depending on the relationship with the addressee and their individual characteristics and abilities, we expect the speaker to use personally appropriate language (e.g. formal/informal, near/distant or simplified/more demanding). Thus, an unexpected change to formal conversation between a couple, relatives or friends may simply implicate something amusing. The reverse – an intentional change to an informal conversational style in a situation requiring a more formal mode of address – can also be used to express dissatisfaction, disrespect, contempt or even the opposite. Alternatively, it can seem impolite to the hearer, with impoliteness or unprofessionalism describing the hearer’s evaluation of a speaker’s linguistic or non-linguistic actions based on the hearer’s personal view of the conventional rules of social conformity.

As with the other principles, the operation of the S-Principle does not require adherence to the T-Principle, or to any other principle. Expectations of social conformity can even take precedence over other principle-based expectations, such as truthfulness, as the following example from Thomas (Reference Thomas1983: 107) illustrates, based on her own experience while teaching at a university in Russia.Footnote 14

At the end of each semester, the Rector of the University called a meeting of each department to discuss how well the teaching staff had fulfilled its plan. This particular semester […] had started six weeks late because the students had been despatched to the state farms to help bring in the potato harvest. Nevertheless, the Rector criticized each teacher individually for having underfulfilled his/her norm and, ludicrous as the situation seemed to me, each teacher solemnly stood up, said that s/he accepted the criticism and would do better next time. […] The anger I aroused, by saying quite politely that I did not think I was to blame, was quite appalling and the reverberations lasted many months. What offended my Soviet colleagues so deeply was that they felt I was being intolerably sanctimonious in taking seriously something which everyone involved knew to be purely a matter of form; behaving like the sort of po-faced prig who spoils a good story by pointing out that it is not strictly true. I, for my part, had felt obliged to sacrifice politeness in the greater cause of (overt) truthfulness! (Thomas Reference Thomas1983: 107)

The situation described by Thomas (Reference Thomas1983) illustrates the strong impact that a violation of the subprinciple S1 (‘Making your contribution culturally appropriate’) can have in certain communities, cultures or social groups. While the author felt compelled to prioritise truthfulness over adherence to S1 – which, from her perspective, meant foregoing politeness – her S1-violating contribution was perceived by her Soviet colleagues as not only incomprehensible but also as intolerably rude. This example shows that the S-Principle may be subject to completely different priority expectations depending on the community. It also illustrates that truthfulness does not always hold the highest priority and that expectations for adherence to the S-Principle can make truthfulness seem secondary in particular cultural contexts.

3. Conclusion

Although several principles may be violated simultaneously or in the same proposition, the reformulated TRICS-Principles operate at different levels. I have demonstrated the extent to which the principles operate under the umbrella of a violated T-Principle and how a principle violation may attenuate or render others more irrelevant. I have also demonstrated that the strength of expectations and the prioritisation of principles depend on various factors and vary according to different social conventions. The prioritisation of certain principles allows for dynamic shifts, such as the increased lowering of expectations of compliance with a principle that has been repeatedly violated and, consequently, the greater impact of an unexpected violation of another principle. I have referred to this as the ‘habituation effect of principle violation’ (HEP).

I have revised the CP and the principles to solve the problems of dual-purpose guideline formulation and the circularities that have contributed to the alleged interdependencies between the principles, particularly between the principles of relevance and informativity. Furthermore, I have introduced the S-Principle, for which I have proposed three subprinciples: making one’s contribution culturally appropriate (S1), register appropriate (S2) and personally appropriate. The S-Principle should not be confused with the stand-alone concept of politeness, although the observance or violation of this principle frequently leads to the subjective perception of (im)politeness.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere thanks to the three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful, constructive and detailed comments, which substantially improved this article. The depth and quality of their feedback were greatly appreciated.

Competing interests

I declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.