At the end of the 2019 term, the Supreme Court dramatically increased workplace protections for LGBTQ individuals when the justices ruled that workplace discrimination based on someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity violated Title VII (Totenberg Reference Totenberg2020). The opinion in Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) came from a surprising source: Justice Neil Gorsuch, who, despite not being particularly supportive of LGBTQ rights early in his tenure (Farias Reference Farias2020), used textualism to explain that a plain text reading of Title VII confirmed that firing someone for being gay or transgender was discrimination because of sex (Stern Reference Stern2020). Three of Gorsuch’s colleagues on the Court criticized the opinion as “a pirate ship” that “sails under a textualist flag” (Gersen Reference Gersen2020), but many legal analysts and commentators on both sides of the political aisle praised Gorsuch’s work (Poindexter Reference Poindexter2020). They suggested that a conservative justice using a conservative approach to write an expansive liberal opinion like this one signaled the decision was legally principled and therefore beyond reproach. Chief Justice John Roberts undoubtedly had this outcome in mind when he assigned the opinion to Gorsuch in the first place (Biskupic Reference Biskupic2020); the most conservative member of the coalition was the best possible defender of this sweeping and controversial liberal decision.

Does knowing that an opinion writer’s ideological preferences or identity characteristics are at odds with the outcome of a Supreme Court case increase support for that outcome? People broadly view the Court as a legally-principled institution (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013), but they react to individual Court opinions using ideological and identity cues (Haglin et al. Reference Haglin, Jordan, Merrill and Ura2020; Zilis Reference Zilis2021). Media coverage of decisions, which tends to focus on ideological winners and losers, helps them do this (Collins and Cooper Reference Collins and Cooper2015; Zilis Reference Zilis2015; Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018). This coverage keeps the public informed of the political consequences of newsworthy cases, but it does so without discussing decisions’ legal underpinnings, which can negatively affect people’s perceptions of the Court (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009; Hall Reference Hall2010). The justices consequently look for ways to turn the conversation about their work back toward the law (Krewson Reference Krewson2019), and one way of doing this is asking a justice whose ideological preferences or identity characteristics are at odds with a path-breaking decision to write the majority opinion for it (Woodward and Armstrong Reference Woodward and Armstrong1979; Epstein and Knight Reference Epstein and Knight1998; Thomas Reference Thomas2019). From a legal standpoint, asking an incongruent justice to write an opinion helps the Court shut down dissent. Beyond that, an incongruent author’s presence can also signal the strength and credibility of a legal opinion (Gibson, Lodge and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014). But is the public listening to that signal and responding to it?

To answer this question, we fielded two survey experiments. In the first, we asked 733 participants to read and respond to a newspaper article about a Supreme Court decision upholding abortion rights, and in the second, we asked 1,497 participants to read about a decision upholding the death penalty. Across both experiments, we varied the ideology and gender of the decision’s opinion writer. All else being equal, we would expect to see that women and Democrats are more likely to support a decision upholding abortion rights (Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Kreitzer, Osborn and Swers2021) and that men and Republicans are more likely to support a decision upholding the death penalty (Jones Reference Jones2018). But if the justices’ instincts are correct and incongruent opinion writers increase support for a controversial and salient decision, we should see an increase in support for decisions written by ideologically- or identity-incongruent justices, especially among people least likely to support that position. Our results suggest that, despite judicial expectations, deploying incongruent justices does not broadly increase support for controversial and salient Supreme Court decisions. Instead, we find that aggregate support remains steady because asking an ideologically-incongruent justice to write a controversial opinion increases support among those least likely to approve of the decision and decreases support from those most likely to approve of it.

This paper significantly contributes to the literature on Supreme Court opinion writing in two distinct ways. First, we connect judicial identity and judicial strategy. The well-developed literature on opinion assignment and construction shows that Supreme Court opinion writers produce decisions that move Court policy toward their preferred outcomes (Maltzman, Spriggs and Wahlbeck Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and Wahlbeck2000). Judicial ideology also influences popular support for decisions, as the public uses cues like the opinion writer’s ideology to evaluate the Court’s work (Boddery and Yates Reference Boddery and Yates2014; Armaly Reference Armaly2018; Zilis Reference Zilis2018). Additionally, scholars suggest that an opinion writer’s identity characteristics, namely their race, ethnicity, and gender, can influence acceptance (Boddery, Moyer and Yates Reference Boddery, Moyer and Yates2020; Ono and Zilis Reference Ono and Zilis2022). Anecdotal evidence indicates the justices both understand and attempt to use identity cues to increase support for a decision (Woodward and Armstrong Reference Woodward and Armstrong1979; Epstein and Knight Reference Epstein and Knight1998). By examining the efficacy of this strategic behavior in two areas where it is most likely to appear, we are one of the first to connect these two lines of literature.

Second, we offer insight into yet another way the justices can harness public support for their work. Because opinion enforcement is at least partially dependent on the Court’s public standing (Hall Reference Hall2010), and the confirmation process and the justice’s own opinions can damage it (Nicholson and Hansford Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014; Badas and Simas Reference Badas and Simas2022), the justices consistently attempt to reinforce the public’s trust in its work, doing everything from aligning their opinions with popular sentiment (Casillas, Enns and Wohlfarth Reference Casillas, Enns and Wohlfarth2011; Hall and Ura Reference Hall and Ura2015), to emphasizing their dependence on precedent (Zink, Spriggs and Scott Reference Zink, Spriggs and Scott2009), to traveling around the county and giving speeches in public forums about the Court’s apolitical role in American government (Black, Owens and Armaly Reference Black, Owens and Armaly2016; Krewson Reference Krewson2019). We suggest the justices also anticipate negative reactions and attempt to head them off where possible by selecting a writer who can move the conversation away from ideology or identity and toward the law itself, which simultaneously fortifies the opinion and the Court’s legitimacy.

Supreme Court opinions and the public

Although much of the Supreme Court decision-making process is private, its end product is wholly public: an opinion, typically attributed to a single justice and joined by at least four others (Hitt Reference Hitt2019), that resolves a legal conflict and provides guidance for future cases (Hansford and Spriggs Reference Hansford and Spriggs2006). Despite the singular byline, the opinion is the collaborative product of ideological preferences and Court rules. The justices’ individual policy preferences and the Court’s broader ideological composition influence case outcomes (Hammond, Bonneau and Sheehan Reference Hammond, Bonneau and Sheehan2005; Lax and Cameron Reference Lax and Cameron2007; Carrubba et al. Reference Carrubba, Friedman, Martin and Vanberg2012), especially those of the Chief Justice, as he often assigns opinions (Johnson, Spriggs and Wahlbeck Reference Johnson, Spriggs and Wahlbeck2005). Additionally, past rulings can limit the justices’ ability to move policy in preferred directions (Black and Spriggs Reference Black and Spriggs2013); five justices must agree on the legal reasoning to establish a precedent (Hitt Reference Hitt2019); the need to complete work by the end of the term forces assignment equity across the justices (Maltzman, Spriggs and Wahlbeck Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and Wahlbeck2000); the justices value issue expertise (Maltzman and Wahlbeck Reference Maltzman and Wahlbeck1996); and dissents and concurrences can force modifications to the majority opinion (Corley Reference Corley2010; Corley and Ward Reference Corley and Ward2020). But once the opinion is complete and released, the Court owns it and is held responsible for its contents.

Public opinion is not supposed to affect the decision-making process. The framers tried to remove the Court from public opinion by staffing it with lifetime appointees, but they then tasked popularly elected officials with decision enforcement (Hamilton Reference Hamilton and Rossiter2003; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008). Implementation is thus more likely when the public supports the decision or believes the justices have the power to make it (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013), so the justices constantly attempt to buttress their authority, creating a “reservoir of good will” that protects the Court from non-enforcement (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira1992). The justices use the trappings of their office to show they work within a legal institution and not a political one (Enns and Wohlfarth Reference Enns and Wohlfarth2013; Gibson, Lodge and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014), make appearances and tell the public about the law’s role in their work (Black, Owens and Armaly Reference Black, Owens and Armaly2016; Krewson Reference Krewson2019), and align most of their decisions with public opinion to avoid looking radical or untrustworthy (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2009; Casillas, Enns and Wohlfarth Reference Casillas, Enns and Wohlfarth2011; Hall and Ura Reference Hall and Ura2015; Nelson and Tucker Reference Nelson and Tucker2021, but see Johnson and Strother Reference Strother2021). These actions work. Although people believe the justices are influenced by politics, they also believe the justices are principled decision makers (Scheb and Lyons Reference Scheb and Lyons2000; Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013), and they consistently express high feelings of legitimacy toward the Court (Gibson, Caldeira and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003), which pressures officials to implement its decisions.

Because the reservoir of good will exists, Supreme Court justices can release unpopular decisions, but they cannot consistently act in a countermajoritarian manner without draining the reservoir (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2011). Although the justices favor majoritarianism (Hall and Ura Reference Hall and Ura2015), however, long-standing practices make it difficult for the Court to show it. The justices release their opinions without elaboration, which, given the difficulty of reading them (Black et al. Reference Black, Owens, Wedeking and Wohlfarth2016), creates an informational vacuum around the Court’s work. The media fills the void, but outlets only cover a few cases each term (Collins and Cooper Reference Collins and Cooper2016), and the public consequently only learns about controversial and newsworthy cases (Zilis Reference Zilis2015). News outlets tend to summarize rather than quote the opinion, and they portray every decision as a battle won by one group and lost by another, typically with ideological implications woven throughout the narrative (Johnston and Bartels Reference Johnston and Bartels2010; Linos and Twist Reference Linos and Twist2013; Davis Reference Davis2014; Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018). This limited coverage offers people the information and cues they need to understand a decision and react to it (Nicholson and Hansford Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014; Armaly Reference Armaly2020; Zilis Reference Zilis2022), but it also removes focus from the legal reasoning of the opinion, makes it easier for the public to disagree with the decision, and suggests the Court is only releasing controversial opinions. Put differently, Court conventions can lead to the justices looking radical, untrustworthy, and unprincipled – the exact things they want to avoid.

Given the reality of the coverage, Supreme Court justices attempt to use the media-worthy parts of their opinion to convey the legal soundness of their decisions and move focus away from outcomes. They approach cases with greater media coverage with more care, taking longer to write opinions and producing more cognitively complex ones too (Badas and Justus Reference Badas and Justus2022). The justices can also use the opinion writer to cue legal soundness. The media may not explain the Court’s full legal justification for reaching a decision (Linos and Twist Reference Linos and Twist2013), but it does mention the opinion writer in most of its coverage,Footnote 1 and, in certain situations, that information can signal the legal propriety of a decision and accordingly increase support for it (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013, Reference Bartels and Johnston2020). The justices have long believed there is power in asking incongruent justices to write controversial decisions. Court members asked a champion of civil liberties to defend the government’s relocation policies in Korematsu v. United States (1944) (Epstein and Knight Reference Epstein and Knight1998); a white Methodist Nixon appointee to write Roe v. Wade (1973) (Woodward and Armstrong Reference Woodward and Armstrong1979); and the only woman on the Court to strike down a women-only college admissions policy in Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan (1982) (Thomas Reference Thomas2019). In each of these cases, the media reported its delighted surprise that that justice wrote this controversial but obviously legally correct opinion. The justices believe that if they can find an incongruent justice to write the opinion in a salient case, that justice’s presence can increase support for the Court’s decision.

Seeing that a female justice wrote an opinion is a useful and disruptive signal that the law might matter, though that signal is issue specific. People use the gender of the majority opinion writer, which is a readily available cue, to evaluate the procedural correctness of an opinion. Research suggests that Democrats believe female judges are fairer than male ones and Republicans believe the opposite, particularly on issues like abortion or immigration, where they fear women’s “soft” natures will lead to lenient rulings (Ono and Zilis Reference Ono and Zilis2022). Simultaneously, people are more likely to support a “tough on crime” search and seizure decision or an anti-abortion ruling when a female justice writes it (Boddery, Moyer and Yates Reference Boddery, Moyer and Yates2020; Matthews, Kreitzer and Schilling Reference Matthews, Kreitzer and Schilling2020), which suggests people respond positively when women act against (heavily stereotyped) behavioral expectations (Heilman and Eagly Reference Heilman and Eagly2008). On family and women’s issues, then, seeing that a man wrote the opinion should lend credibility to the proceedings and increase support among the Republicans least likely to support them; on criminal issues, however, seeing that a woman wrote the opinion should increase support among those least likely to support it, namely women and Democrats.

Ideologically-incongruent justices are also easy to identify, and their presence sends a strong message about the power of the law. The public struggles to evaluate Supreme Court outcomes without the help of heuristics like partisanship or ideology (Nicholson and Hansford Reference Nicholson and Hansford2014; Zilis Reference Zilis2022), but when they have that information, they use it and respond accordingly (Zilis Reference Zilis2015; Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018). When that cue is not clearly available, people use opinion writers’ ideologies to work through decisions (Boddery and Yates Reference Boddery and Yates2014; Clark and Kastellec Reference Clark and Kastellec2015; Zilis Reference Zilis2021). But what happens when the press reports competing messages, like announcing that a justice wrote an ideologically distant opinion? The justices clearly believe competing cues draw attention toward the legal correctness of the decision, but this effect should be conditional. For the people pleased with the outcome, seeing that an ideologically-incongruent justice wrote the opinion should simply bolster their belief that the Court got the answer right (Armaly Reference Armaly2020; Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020), and their support should remain high. But for the people displeased with the outcome, seeing that an ideologically-incongruent justice wrote an opinion should draw attention away from the outcome and toward the legal correctness of the decision and increase support from those people in the process.

Given these expectations and the justices’ own assumptions about incongruent opinion writers, we hypothesize the following:

H1: Opinions written by an identity-incongruent justice should have higher overall support than those written by an identity-congruent justice.

H2: Opinions written by an ideologically-incongruent justice should have higher overall support than those written by an ideologically-congruent justice.

Additionally, because our theory leads us to believe that incongruent opinion writers target specific groups, we also hypothesize the following:

H3: Opinions written by an identity-incongruent justice should increase public support for a Supreme Court decision among people most likely to disagree with the opinion.

H4: Opinions written by an ideologically-incongruent justice should increase public support for a Supreme Court decision among people most likely to disagree with the opinion.

Motivation and approach

We want to know if and how support for a salient and ideologically charged Supreme Court opinion changes when the public sees that an ideologically- or identity-incongruent justice wrote the opinion. To do this, we conducted two separate 2 x 2 survey experiments. Participants in the first experiment read about an unnamed Supreme Court decision overturning a state law that unduly burdened women’s access to abortion, based on the Court’s ruling in Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016) (Liptak Reference Liptak2016), and participants in the second experiment read about a ruling allowing three death row inmates’ executions to proceed, based on Glossip v. Gross (2015) (Liptak Reference Liptak2015).Footnote 2 In both experiments, participants in the treatment groups learned that either a liberal or conservative justice, who was male or female, wrote the majority opinion in the case, whereas participants in the control group did not see any information about the opinion writer.Footnote 3

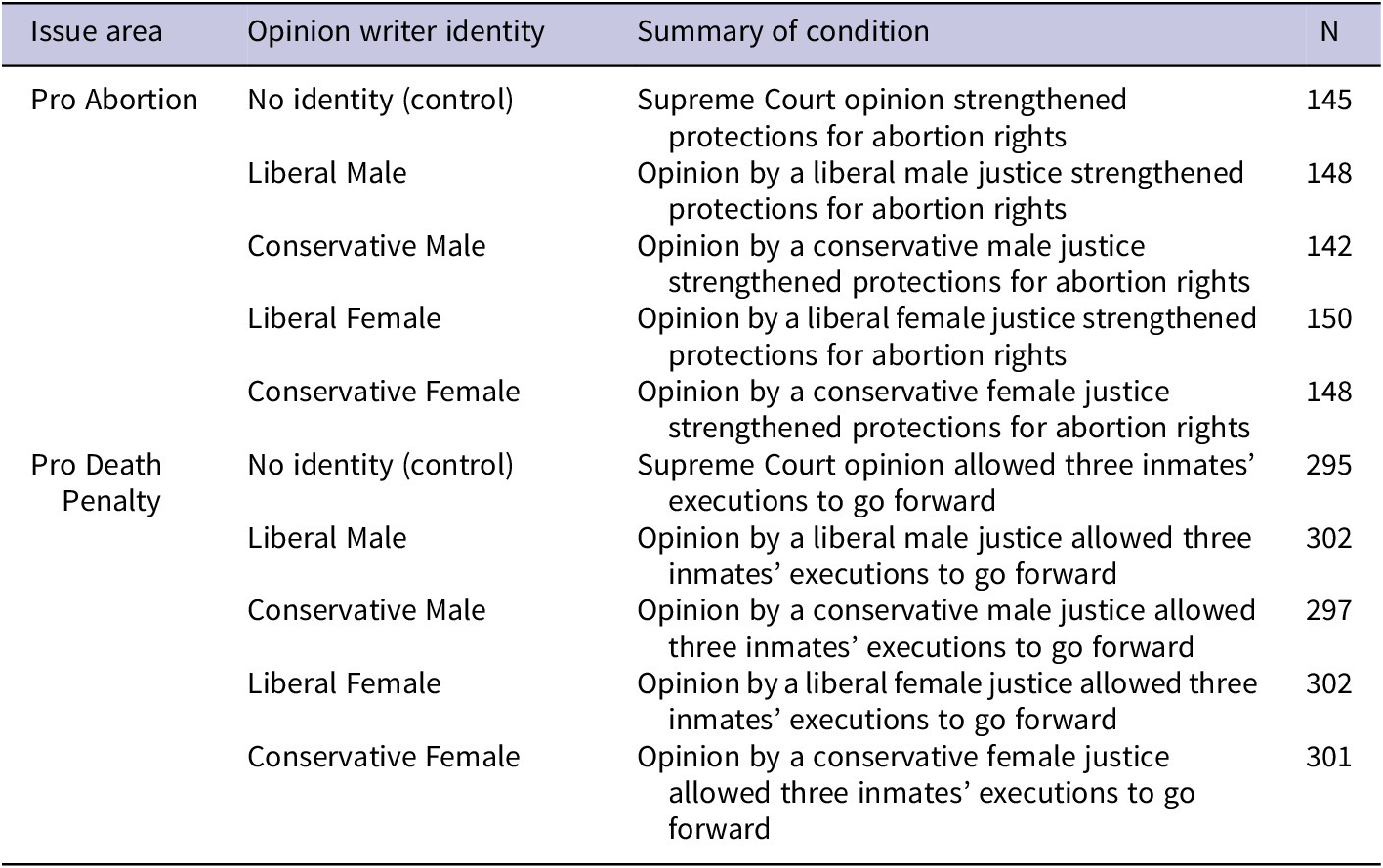

We used Lucid Theorem to recruit two nationally representative samples of participants to complete our surveys (Coppock and McClellan Reference Coppock and McClellan2019).Footnote 4 In the first survey, fielded between March 29 and April 11, 2021, we asked 733 participants to respond to the decision upholding abortion rights.Footnote 5 For the second survey, fielded between September 23 and October 14, 2022, we asked 1,497 participants to respond to the decision allowing inmates’ death sentences to proceed.Footnote 6 Table 1 provides a summary of the treatments as well as the number of participants assigned to each group.Footnote 7

Table 1. Experimental Conditions

We structured both experiments the same way. After consenting to take the survey, participants answered a handful of questions about the Court before they were randomly sorted into their treatment or control groups and asked to read the newspaper vignette. We then asked participants to identify the profile of the justice who wrote the opinion,Footnote 8 followed by several questions about the participant’s feelings regarding the decision, the Supreme Court broadly, and their general feelings regarding abortion or the death penalty. We measured participant feelings using a combination of feeling thermometers (0 to 100) and agree/disagree/no opinion questions. We prefaced these questions by restating the profile of the justice who wrote the opinion, asking, “On a scale from 0 to 100, how would you rate the [conservative/liberal] [male/female] justice’s decision in this [abortion/death penalty] case?” Participants in the control group were asked about the Court’s unattributed decision. For our final question, we asked participants if they thought the Court should be deciding cases in this particular issue area. At the end of each survey, we debriefed the participants and told them that the news article they read was fictional.

We focused our analysis on abortion and the death penalty for several different reasons. First, abortion and the death penalty are salient issues that garner media coverage (Collins and Cooper Reference Collins and Cooper2016), which means people realistically learn about and respond to the Supreme Court’s work in these areas (Zilis Reference Zilis2015; Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018); that is, these are issues where the justices would realistically deploy an incongruent opinion writer if one was in the majority coalition.Footnote 9 Second, we selected two issue areas with policy preferences that are easily associated with specific ideologies: democrats support abortion rights and Republicans oppose them,Footnote 10 while Republicans support the death penalty and Democrats oppose it.Footnote 11 Third, abortion is considered a woman’s issue and the death penalty is not (Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Kreitzer, Osborn and Swers2021), so these issues allow us to examine the role gender plays in response to decisions on a woman’s issue and a more general one. Finally, the Court did not review any cases in these areas during our experimental periods, which limited the potential for external or recency bias to interfere with our results.

Results

To examine participants’ support for the Supreme Court’s decision in a pro-abortion or pro-death penalty decision, we used feeling thermometers.Footnote 12 The higher the score, the greater the support for the decision, with a zero indicating cold and negative feelings toward the decision and a 100 indicating warm and positive feelings toward it. For both the abortion and death penalty vignettes, the median thermometer score was 60 and the mean was between 58 and 59, indicating that, on average, participants were more likely to support the Court’s decision than oppose it.

Generally speaking, there are significant ideological differences in overall support. When considering support for a decision upholding abortion rights, participants who identified as Democrats had an average thermometer score of 68, which is significantly higher than the average thermometer score for participants who identified as Republicans (51, p

![]() $ < $

0.05) and Independents (53, p

$ < $

0.05) and Independents (53, p

![]() $ < $

0.05). The opposite is true regarding a decision upholding the use of the death penalty, as participants identifying as Republicans had an average thermometer score of 69, which is significantly higher than the scores for participants who identified as Democrats (55, p

$ < $

0.05). The opposite is true regarding a decision upholding the use of the death penalty, as participants identifying as Republicans had an average thermometer score of 69, which is significantly higher than the scores for participants who identified as Democrats (55, p

![]() $ < $

0.05) and Independents (54, p

$ < $

0.05) and Independents (54, p

![]() $ < $

0.05). Women are not significantly more supportive of a pro-abortion decision (average thermometer of 61 for women and 57 for men, p

$ < $

0.05). Women are not significantly more supportive of a pro-abortion decision (average thermometer of 61 for women and 57 for men, p

![]() $ = $

0.13), but they are significantly less supportive of a decision supporting the death penalty than men (average thermometer of 57 for women and 64 for men, p

$ = $

0.13), but they are significantly less supportive of a decision supporting the death penalty than men (average thermometer of 57 for women and 64 for men, p

![]() $ < $

0.05).

$ < $

0.05).

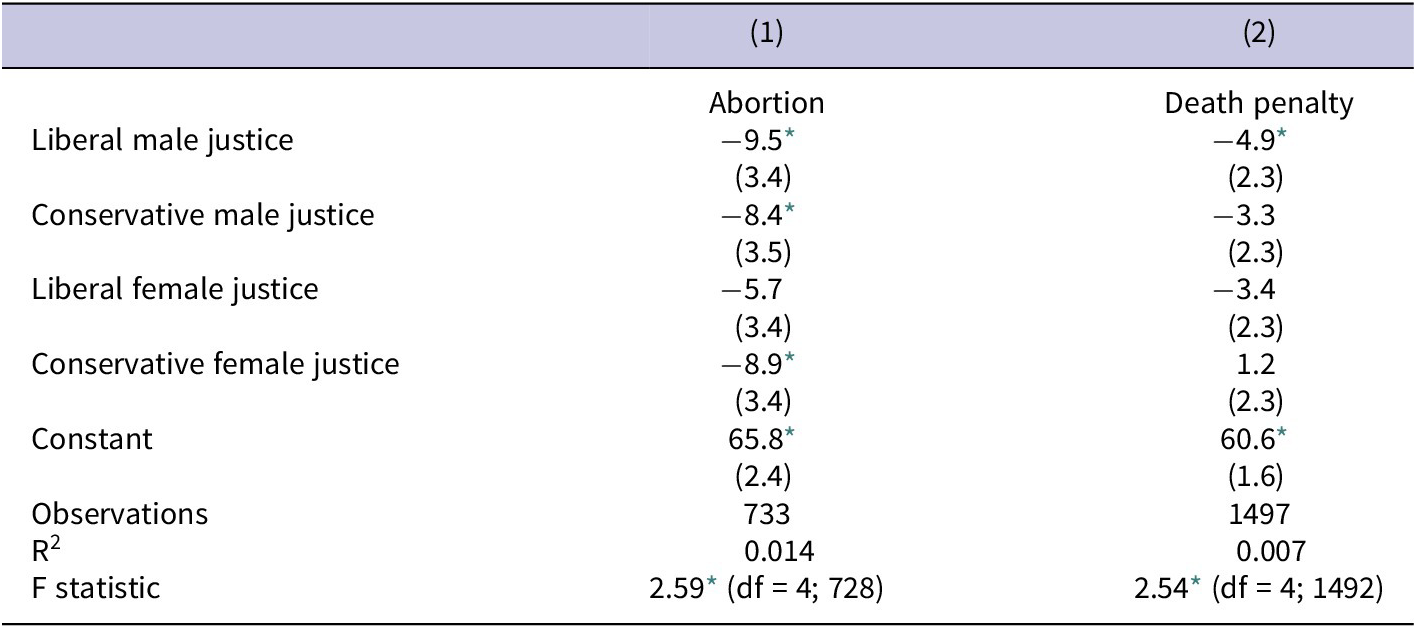

Our first objective is to see if participants broadly respond differently to opinions attributed to certain justices. As we stated in Hypotheses 1 and 2, the justices’ historical use of incongruent opinion writers leads us to hypothesize that overall support for salient and controversial decisions should increase when an identity-incongruent (Hypothesis 1) or ideologically-incongruent (Hypothesis 2) justice writes the opinion. To test these hypotheses, we turned to the direct treatment effects. We utilized ordinary least squares (OLS) regression, with the feeling thermometer of support for the Court’s opinion as the dependent variable, the different treatment groups (liberal male opinion writer, conservative male opinion writer, liberal female opinion writer, conservative female opinion writer) as the independent variables, and the control group acting as the comparison category. Table 2 contains our analysis of the support for the abortion rights decision in Model 1 and for the death penalty decision in Model 2.

Table 2. OLS results, Decision Thermometer, Direct Effects

* p < 0.05

If incongruent justices increase broad support for a pro-abortion decision, we would expect to see that people are more supportive of a pro-abortion decision when an ideologically-incongruent conservative justice or an identity-incongruent male justice wrote the opinion. As the results in Model 1 of Table 2 show, contrary to our hypotheses, we do not find that to be true. Instead, participants who read about an unattributed decision upholding abortion rights expressed significantly higher support for the decision (66) than did the participants who read about a liberal male (56, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), conservative male (56, p

$ < $

0.05), conservative male (56, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), or conservative female justice writing the opinion (57, p

$ < $

0.05), or conservative female justice writing the opinion (57, p

![]() $ < $

0.05). Participants who read about an identity-incongruent male justice or an ideologically-incongruent conservative justice writing the opinion did not express higher support for it. Interestingly, participants who read about a liberal female justice writing such an opinion were as supportive as the participants who read about an unattributed opinion (60, p

$ < $

0.05). Participants who read about an identity-incongruent male justice or an ideologically-incongruent conservative justice writing the opinion did not express higher support for it. Interestingly, participants who read about a liberal female justice writing such an opinion were as supportive as the participants who read about an unattributed opinion (60, p

![]() $ = $

0.09).

$ = $

0.09).

Applying the same logic to the death penalty experiment, if incongruent justices increase broad support, we would expect to see that people are more supportive of a pro-death penalty experiment when an ideologically-incongruent liberal justice or an identity-incongruent female justice wrote the opinion. Turning to Model 2 of Table 2, we again see that no one opinion writer profile increases broad support for a Supreme Court decision that upholds the death penalty. The average participant who read about an unattributed decision allowing inmates’ executions to go forward had a feeling thermometer score of 61, which is no different from the feeling thermometer scores for anyone who read about a liberal female (57, p

![]() $ = $

0.13), conservative male (57, p

$ = $

0.13), conservative male (57, p

![]() $ = $

0.15), or conservative female justice writing the opinion (59, p

$ = $

0.15), or conservative female justice writing the opinion (59, p

![]() $ = $

0.61). Participants who read about a decision written by a liberal male justice, however, were significantly less supportive of the Court’s decision to uphold the death penalty than were those in the control group (56, p

$ = $

0.61). Participants who read about a decision written by a liberal male justice, however, were significantly less supportive of the Court’s decision to uphold the death penalty than were those in the control group (56, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), again showing the opinion writer does little to increase broad support for the decision – congruent or not.

$ < $

0.05), again showing the opinion writer does little to increase broad support for the decision – congruent or not.

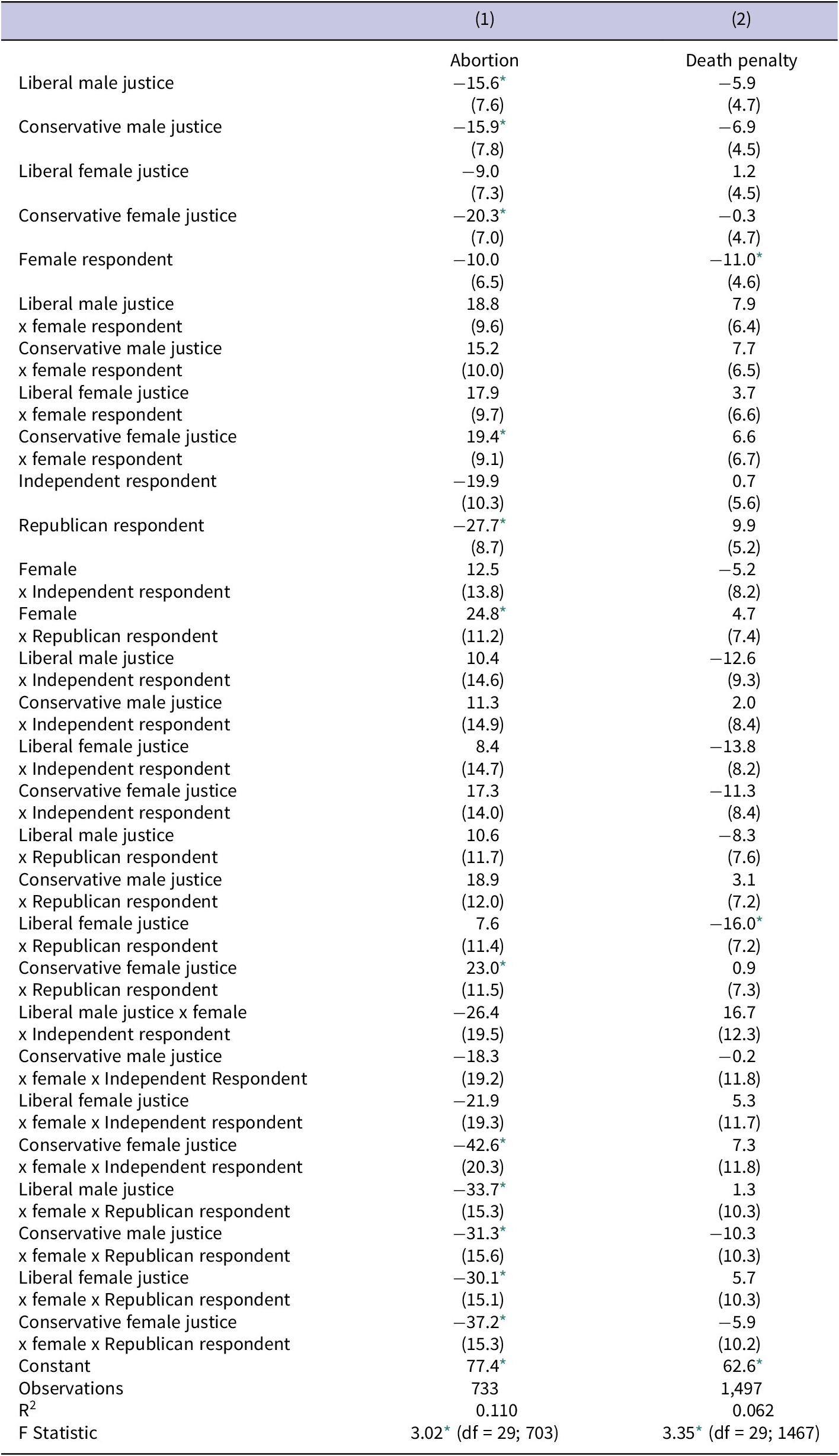

Despite having found no support for our hypotheses that incongruent opinion writers universally increase support for a Supreme Court decision, we still wanted to know if seeing that a certain justice wrote an opinion increased support for it among those predisposed not to like it. As we explained in Hypotheses 3 and 4, we expect that incongruent justices specifically increase support among those least likely to support the Court’s decision in the first place. To address these hypotheses, we looked at participant support for a Supreme Court decision given their treatment group, partisanship, and gender. We again used OLS for this analysis, and the results are presented in Table 3.Footnote 13

Table 3. OLS Results, Decision Thermometer, Expanded Models

* p < 0.05

Again, beginning with the abortion experiment, the results in Figure 1 show that Democrats (left) are more likely to support the decision than are Republicans (right).Footnote 14 As the left side of Figure 1 shows, there are small differences in support between male and female Democrats. Male Democrats’ support for a pro-abortion decision did not significantly change based on the treatment they received, but they did feel significantly more positive about an unattributed majority opinion (77) than they did about one written by a liberal male (62, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), conservative male (62, p

$ < $

0.05), conservative male (62, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), or conservative female justice (57, p

$ < $

0.05), or conservative female justice (57, p

![]() $ < $

0.05). Mirroring the results of the direct treatment effects in Table 2, only a liberal female justice writing an opinion garners as much support as the unattributed decision in the control group (77 vs. 68, p

$ < $

0.05). Mirroring the results of the direct treatment effects in Table 2, only a liberal female justice writing an opinion garners as much support as the unattributed decision in the control group (77 vs. 68, p

![]() $ = $

0.22). Conversely, female Democrats’ support for a pro-abortion decision remains high across all four treatments and the control group; no matter who wrote the opinion, female Democrats felt supportive of it. The right side of Figure 1 demonstrates that, for the most part, support among Republican participants does not differ from an unassigned opinion, regardless of gender. The only outlier is when female Republicans are less supportive of opinions written by a liberal male justice (45, p

$ = $

0.22). Conversely, female Democrats’ support for a pro-abortion decision remains high across all four treatments and the control group; no matter who wrote the opinion, female Democrats felt supportive of it. The right side of Figure 1 demonstrates that, for the most part, support among Republican participants does not differ from an unassigned opinion, regardless of gender. The only outlier is when female Republicans are less supportive of opinions written by a liberal male justice (45, p

![]() $ < $

0.05).

$ < $

0.05).

Figure 1. Mean differences in participant feelings toward Supreme Court’s decision strengthening abortion rights for Democrat (left) and Republican (right) participants. Vertical bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Examining these results in more detail, the expectations outlined in Hypotheses 3 and 4 suggest that seeing that an incongruent male or conservative justice wrote an opinion upholding abortion rights should increase support for that decision among those least likely to agree with it, namely among men and Republicans. Figure 2a shows the differences in support between male and female participants for pro-abortion decisions, broken down by partisanship. Aligning with the results we provided in Figure 1, there are no gendered differences in support in our data: male and female Democrat participants are equally likely to support an Supreme Court decision upholding the death penalty regardless of who wrote it, as are male and female Republican participants. This finding is unsurprising, given that gendered differences in abortion support are not always as obvious as the partisan ones (Lizotte Reference Lizotte2020), but it does not align with our expectation in Hypothesis 3.

Figure 2. First differences of participant feelings toward Supreme Court’s decision strengthening abortion rights by (a) participant gender (Democrats left, Republicans right) and (b) participant partisanship (male left, female right). Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

But, as we also showed in Figure 1, there are real partisan differences in support of a decision upholding abortion rights, and, when examining the different reactions across partisans, we see that having an ideologically-incongruent justice write the opinion matters. Looking at Figure 2b, partisan differences disappear when certain opinion writers take the lead. Aligning with our expectations, we see that when a conservative justice wrote the opinion, the partisan difference in support disappears for male participants. But upon further examination, this result is slightly more complicated: when either a male or female conservative justice wrote the opinion upholding abortion rights, Republican men become more supportive of the decision, but when a female conservative justice wrote the opinion, support among male participants identifying as Democrats decreased. This means that in the aggregate, the Court ends up with about the same level of support for the decision. The right side of Figure 2b provides evidence that, among women, Democrat participants are always more supportive of a decision than Republicans, unless the opinion is unattributed, at which point support is high from both female Democrat and female Republican participants. We consequently find some support for Hypothesis 4, though the results suggest that increasing support with the people least likely to support the decision comes at the cost of decreasing support among those most likely to support it in the first place.

Shifting our attention to the death penalty experiment, Figure 3 shows Democrats (left) are less supportive of a pro-death penalty decision than Republicans (right). As the left side of Figure 3 demonstrates, neither male nor female Democrats vary in their support of opinion writers for death penalty decisions. That is, who writes the opinion does not alter support for a decision for Democratic participants. The right side of Figure 3 shows a similar pattern for Republican women, whose support for a pro-death penalty decision remains constant regardless of the opinion writer. Republican men, however, do express different levels of support for an opinion when the author changes. Republican men prefer opinions authored by a conservative female justice (73, p

![]() $ < $

0.05) or opinions attributed to the Court (73, p

$ < $

0.05) or opinions attributed to the Court (73, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), compared to a liberal male justice (58). Similarly, Republican men show higher support for a decision penned by a conservative male justice (69, p

$ < $

0.05), compared to a liberal male justice (58). Similarly, Republican men show higher support for a decision penned by a conservative male justice (69, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), conservative female justice (73, p

$ < $

0.05), conservative female justice (73, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), or the Court (73, p

$ < $

0.05), or the Court (73, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), than they do for an opinion written by a liberal female justice (58).

$ < $

0.05), than they do for an opinion written by a liberal female justice (58).

Figure 3. Mean differences in participant feelings toward Supreme Court’s decision upholding the use of the death penalty for Democrat (left) and Republican (right) participants. Vertical bars show 95% confidence intervals.

For our death penalty experiment, Hypotheses 3 and 4 lead us to expect that support for a pro-death penalty decision increases among female and Democratic participants when a female or liberal justice wrote the opinion. Figure 4a provides the differences in support by male or female participants by partisanship. Across all but one category, there is no difference in female and male support for death penalty opinions for Democrats or Republicans. The sole exception is in the control group for Democrats, as female participants are significantly less supportive of death penalty opinions “by the Court” than male participants (52 vs. 62, p

![]() $ < $

0.05). When combined with the results of the abortion experiment, these results suggest that, contrary to Hypothesis 3, seeing that an identity-incongruent justice wrote an opinion does not increase support for the Court’s decision.

$ < $

0.05). When combined with the results of the abortion experiment, these results suggest that, contrary to Hypothesis 3, seeing that an identity-incongruent justice wrote an opinion does not increase support for the Court’s decision.

Figure 4. First differences of participant feelings toward Supreme Court’s decisions strengthening the death penalty by (a) participant gender (Democrats left, Republicans right) and (b) participant partisanship (male left, female right). Vertical bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Turning next to Figure 4b, we see the first differences in support for death penalty decisions by partisanship amongst male and female participants. The left side of Figure 4b provides evidence of partisan variation in support by opinion author for male participants. Republican men are more supportive than Democratic men of a pro-death penalty opinion written by a conservative male justice (69 vs. 56, p

![]() $ < $

0.05) or a conservative female justice (73 vs. 62, p

$ < $

0.05) or a conservative female justice (73 vs. 62, p

![]() $ < $

0.05). Interestingly, when a liberal male justice (p

$ < $

0.05). Interestingly, when a liberal male justice (p

![]() $ = $

0.77), liberal female justice (p

$ = $

0.77), liberal female justice (p

![]() $ = $

0.22), or the Court itself (p

$ = $

0.22), or the Court itself (p

![]() $ = $

0.06) produced the opinion, those partisan differences disappear. But, as we saw with the abortion experiment, the elimination of this gap is not necessarily what the justices want to see, as it is driven by Republican men, who are most likely to support the death penalty, withdrawing support when a liberal justice wrote the opinion.

$ = $

0.06) produced the opinion, those partisan differences disappear. But, as we saw with the abortion experiment, the elimination of this gap is not necessarily what the justices want to see, as it is driven by Republican men, who are most likely to support the death penalty, withdrawing support when a liberal justice wrote the opinion.

The right side of Figure 4b shows similar results for the partisan differences between female participants. Republican women exhibit higher support than Democratic women when an pro-death penalty opinion is written by a conservative female justice (68 vs. 58, p

![]() $ < $

0.05) or “by the Court” (66 vs. 52, p

$ < $

0.05) or “by the Court” (66 vs. 52, p

![]() $ < $

0.05), and there are no partisan differences when a liberal male or a liberal female justice produces the difference. Once again, these results are driven by decreases in Republican support and not increases from Democrats. When combined with our findings from the abortion experiment, these results suggest that ideologically-incongruent justices do modify support for a Supreme Court decision, just not in the manner the justices intended. They eliminate partisan differences, but they do so by holding steady or slightly increase support from one group at the expense of those most likely to support the decision in the first place.

$ < $

0.05), and there are no partisan differences when a liberal male or a liberal female justice produces the difference. Once again, these results are driven by decreases in Republican support and not increases from Democrats. When combined with our findings from the abortion experiment, these results suggest that ideologically-incongruent justices do modify support for a Supreme Court decision, just not in the manner the justices intended. They eliminate partisan differences, but they do so by holding steady or slightly increase support from one group at the expense of those most likely to support the decision in the first place.

Conclusion

At least a few times each term, the typically placid Supreme Court wades into a salient and controversial debate and draws media attention and fire when the justices eventually release their decisions in it to the world. Although the justices cede control over the direction that conversation takes (Zilis Reference Zilis2015; Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018), they can use certain high-value signals, like the opinion writer’s ideology and identity, to show the public their dedication to the law and increase support for that decision. History shows that Supreme Court justices believe that an opinion writer’s attributes can influence acceptance of a case by the public, and the justices strategically assign certain opinions with that belief in mind. We sought to better understand how those strategic decisions influence public support for the Court’s decision. We found that incongruent opinion writers never broadly increase support for a decision. Instead, we found that incongruent opinion writers specifically target the people least likely to support a controversial decision, at the cost of pre-existing support.

In this manuscript, we find that strategically selected opinion writers whose ideology is at odds with a decision can influence support for Supreme Court decisions, though not in the manner the justices intended. Although identity-incongruent justices do not move public opinion at all in other pro-abortion or pro-death penalty decisions, ideologically-incongruent justices can shift opinion, though they are essentially robbing Peter to pay Paul: they incrementally increase or hold steady the support offered by those least likely to support the Court’s decision, but they do so at the cost of losing support among those most likely to agree with the justices. The justices have long acknowledged they strategically select justices to write opinions, and our results suggest that, although this strategy may not increase support in the aggregate, it can reduce partisan divides in support.

Is asking an incongruent justice to write an opinion worth the effort, then? Although our experiment suggests employing incongruent opinion writers results in limited benefits, attempting to reduce negative support is always worth the effort. The Court’s approval has declined in recent years (Haglin et al. Reference Haglin, Jordan, Merrill and Ura2020), and the justices have both acknowledged this problem and done things to correct it. They go to law schools, policy centers, and think tanks to explain the legal nature of their jobs to the public (deVogue Reference deVogue2021; Ramsey Reference Ramsey2021; Barnes Reference Barnes2022); they transmit oral argument in real time so the public can hear their process (Cordova Reference Cordova2021); and sometimes the justices even shift their positions to keep the Court from looking ideological (Toobin Reference Toobin2012). None of these actions are entirely successful. Justices Barrett and Alito got lambasted for delivering their comments to fawning conservative crowds (Benen Reference Benen2021; Lithwick Reference Lithwick2021), the novelty of listening to oral argument eventually dropped off (Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth Reference Houston, Johnson and Ringsmuth2023), and Chief Justice John Roberts is persona non grata in most conservative circles because he voted to uphold the Affordable Care Act (Kaplan Reference Kaplan2018); however, the justices still try to protect their institution (Biskupic Reference Biskupic2019; Litman, Murray and Shaw Reference Litman, Murray and Shaw2020). Asking incongruent justices to write opinions in salient cases is just another way of doing this. And, importantly, this option is an increasingly available one as the Court continues to diversify in different ways (Greenhouse Reference Greenhouse2021; Howe Reference Howe2022). History suggests that if the option is available, the justices will use it.

In the future, scholars could expand this research by looking at other salient issue areas and by looking at different types of identities. We focused on two obvious identity characteristics in obviously gendered and ideological issue areas and found limited support for identity mattering here, but many other identities can be salient to Supreme Court decision-making at different times (Baum Reference Baum2006; Epstein and Knight Reference Epstein and Knight2013). Future work could examine how a justice’s race might affect support for a decision in an affirmative action case, or how a justice’s status as a parent might affect support for gun rights or the death penalty, or how a justice’s religion might affect support for the death penalty. Scholars could also compare effects across decisions that uphold or restrict certain rights and see if the public responds differently when the Court gives and takes. Our decision to use single survey experiments limits our ability to examine the more dynamic effects of this process, but future scholars could employ multiple survey waves to examine this process.

Scholars could also use real-time public opinion measures of support to see how support changes over time. Although we designed our experiment to simulate the real-world process through which people consume information about the Supreme Court and therefore maximize external validity (Zilis Reference Zilis2015), the design also limits our ability to see how long this effect lasts. One could use survey data to look at real-time effects both immediately after an opinion gets released and over the course of several months. Our results suggest that strategically assigning opinions affects immediate support for a decision, but looking at these effects long-term is important too. There is, in short, always more work to be done.

Acknowledgments

We thank Miles Armaly, Ryan Black, Eileen Braman, Elizabeth Connors, Matt Cota, Cody Drolc, Elizabeth Lane, Jamil Scott, Kelsey Shoub, Katelyn Stauffer, the Law and Courts Women Writing Group, and our anonymous reviewers for their assistance with this manuscript, and Rachel Brooks, Rosemary Edwards, and Kaitlyn McCue for their research assistance. Replication materials available on the Harvard Dataverse, located at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZHZIGE.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jlc.2023.15.