Introduction

In February 2011, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights issued a ruling in the case of Gelman v. Uruguay, its first decision on dictatorship-era human rights violations in Uruguay.Footnote 1 The judgment declared the 1986 ‘Ley de Caducidad de la Pretensión Punitiva del Estado’Footnote 2 (hereafter ‘Ley de Caducidad’ or ‘Amnesty Law’; we use the Spanish and English terms interchangeably) a violation of international human rights law and ordered it overturned. The law granted amnesty for military and security personnel from prosecution for crimes committed between 1973 and 1985 – the official years of the nation’s military dictatorship.Footnote 3

In the ruling’s aftermath, many victims and civil society groups were cautiously optimistic that the Inter-American Court’s decision would help compel the country to open opportunities for them to pursue accountability. Indeed, both press and interviews at the time reveal a sense that the Gelman decision would be a pivotal moment in shifting the country’s intransigent impunity.Footnote 4 Liliana Tojo, programme director for the Centro por la Justicia y el Derecho Internacional (Centre for Justice and International Law, CEJIL), the organisation that helped litigate the case, explained at the time that ‘the Court has finally dictated that Uruguay cannot continue to seek excuses for maintaining impunity for the victims of torture and other horrendous crimes’.Footnote 5

Key international and domestic factors buoyed this optimistic outlook. On an international level, the ruling happened at the same time as the so-called ‘justice cascade’, where international norms about the possibility for trials began to shift away from impunity and towards holding state officials accountable for human rights violations.Footnote 6 Perhaps even more importantly at a domestic level, Uruguay seemed particularly well placed to comply. It held a strong human rights record, a robust commitment to political rights, civil liberties and social inclusion, and had the capacity to combat corruption.Footnote 7 Lastly, Uruguay appeared to possess three characteristics that scholars have identified as key facilitating factors to produce compliance: a strong civil society, political will from a sympathetic governing party, and a progressive judiciary.Footnote 8 Indeed, just eight months after the Court’s decision, in October 2011, Uruguay complied with part of the Inter-American Court’s judgment and officially revoked the Amnesty Law. Subsequently, victims petitioned to have cases that were previously stalled due to the Amnesty Law ‘unarchived’ and filed many new cases as well.

Yet, the cautious optimism surrounding the potential for trials stood in contrast to available evidence about compliance with Inter-American Court rulings to provide legal accountability. At the time of the Gelman judgment, the Court had ordered states to investigate, prosecute and punish (if warranted) in 68 separate judgments, targeted at numerous different countries, but none had ever fully done so.Footnote 9 Given its strong institutions and civil society, many hoped that Uruguay would counter those trends and live up to the hopes of so many onlookers regarding its potential to comply. Yet, this was not to be the case. In the years since the Gelman decision and the law’s repeal, Uruguay’s compliance with the ordered remedy of pursuing criminal trials has been spotty at best. Instead, the path towards accountability has been characterised by judicial backpedalling, intransigence and a struggle to harness sufficient political will.

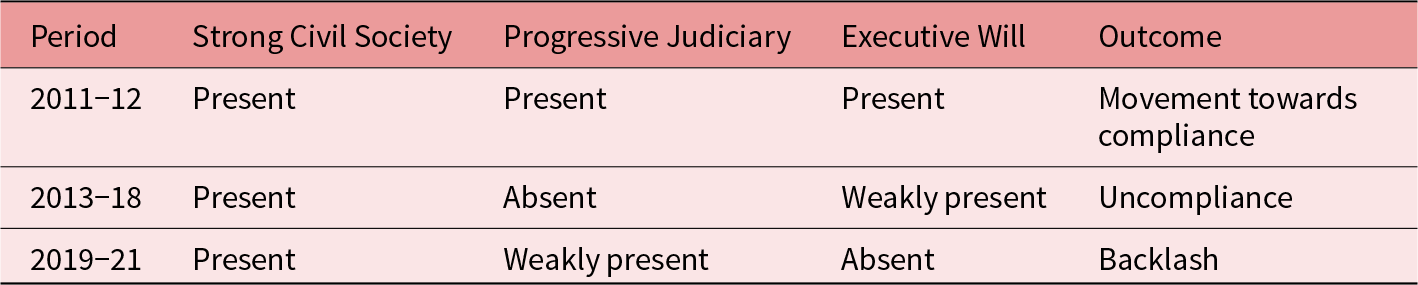

This article examines what happened in those first ten years after the decision, and why, even in a strong democracy, compliance with judicial accountability was so challenging. It leverages within-case variation that exists along the dimensions of civil society, a progressive judiciary and executive political will in the decade since the Gelman ruling, focusing on outcomes in three distinct periods: 2011–12, 2013–18 and 2019–21.Footnote 10 While previous scholars have analysed both general rates of compliance with Inter-American Court orders and the initial Gelman ruling, this article is the first to examine the Gelman case within a ten-year timeframe of its initial judgment.Footnote 11 We do this by carrying out historical analyses of empirical evidence, which includes 18 historical interviews and oral histories, contemporaneous accounts from 13 different Uruguayan and international newspapers, press releases from eight different NGOs, Uruguayan government documents and statements, and all available documents, decisions, press releases and compliance reports from the Inter-American System of Human Rights.Footnote 12 In examining these documents, we analyse continuities and changes over these distinct timeframes.

Previous literature on compliance tends to fit into two categories. On the one hand, scholars have used large-scale datasets to analyse trends with compliance over long timeframes and across countries.Footnote 13 Yet, these studies can only tell us what is true about compliance in aggregate and on average, and do not necessarily explain compliance in any one specific case. Other scholars examine compliance with a particular ruling; for example, there is a wealth of scholarship examining the Gelman case. However, the previous scholarship on the Gelman case has tended to concentrate on the aftermath of the initial years of the decision, which does not offer an analysis of the changing conditions over time.Footnote 14 The ten-year horizon of the Gelman case, in a country with seemingly strong institutions and human rights norms, offers the opportunity to look more closely at the changes in compliance conditions over time. This is particularly important since the process towards full compliance in this case has been non-linear, complete with moments of progress, delay and reversal. In this way, this article adds to scholarship on the Inter-American Court by speaking to the importance of tracking compliance over the longue durée to understand the impact of shifting domestic conditions that structure the challenges and non-linear nature of compliance, even in established democracies.

Compliance and Uncompliance in the Gelman Case

Background

Argentine author and poet Juan Gelman’s attempts to pursue justice in Uruguay for his son, Marcelo Gelman, and daughter-in-law, María Claudia García Iruretagoyena de Gelman, demonstrate the large-scale impunity so many Uruguayans have faced. His pursuit originated in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where his son and pregnant daughter-in-law were disappeared in 1976 when the Argentine military abducted the couple, who were politically active and involved in several leftist movements. The military sent Marcelo to one of the more infamous clandestine detention centres, Automotores Orletti in Buenos Aires, where he was tortured and killed. María Claudia was transferred to a clandestine detention centre in Uruguay operated by the Servicio de Información de Defensa (Defence Information Service, SID), as part of Operation Condor, the coordinated repressive campaign against perceived leftists between right-wing Southern Cone military governments in the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote 15 The couple’s daughter, Macarena, was born in a Montevideo military hospital. María Claudia was never heard from again, and her remains have yet to be found. Macarena was left on the doorstep of a Uruguayan police officer, Ángel Tauriño, whose family adopted the girl.Footnote 16

Macarena grew up unaware of her own history, and her experience was not an isolated incident. According to human rights groups, as many as 500 children in Argentina and Uruguay were taken from their imprisoned parents and given to childless military or police couples whom the military regimes favoured.Footnote 17 Juan Gelman, aware of his daughter-in-law’s pregnancy at the time of her abduction and the military’s practice of giving babies born in captivity to other families, searched tirelessly for his granddaughter.Footnote 18 It was only with the help of a DNA data bank created by Las Abuelas (‘The Grandmothers’) de la Plaza de Mayo – an NGO established with the aim of matching children taken away during the military dictatorship with their birth families – that he finally found Macarena in 1999.

Gelman sought accountability for the crimes committed against his family in Uruguay. However, his appeals to both the executive and judicial branches were blocked, in large part due to the Ley de Caducidad, despite his resources and globally renowned status as a writer.Footnote 19 As a result of the state’s unwillingness to pursue their claims, Gelman and his granddaughter appealed to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in 2006.Footnote 20 The Commission submitted the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2010.

The hearings took place in Quito, Ecuador. Gelman, represented by CEJIL and lawyer José Luis González, provided testimony, and was joined by other witnesses and experts who had worked on the case and could testify about María Claudia’s disappearance. Uruguay did not present any witnesses or experts.Footnote 21 At the time of the hearings, the political climate had changed from the period in which the Gelmans had initially filed the case. Uruguay had elected a president, Tabaré Vázquez, from the leftist Frente Amplio party for the first time and there were signs of executive willingness to pursue justice. As early as 2005, Vázquez had sought to invoke Article 4 of the Ley de Caducidad, which allows for the executive to investigate the disappearance of individuals, to advance the Gelman case in the domestic judicial system; however, his efforts were stymied by an intransigent judiciary, which was unwilling to open the case.Footnote 22

In February 2011, a few months after hearing Gelman’s case, the Inter-American Court issued its ruling. It found Uruguay responsible for forced disappearances committed during its dictatorship for the very first time, deciding Uruguay had violated several articles of the American Convention on Human Rights, including the right to life, right to humane treatment, and right to due process, among others.Footnote 23 Additionally, the Court declared that Uruguay’s Ley de Caducidad was a violation of its obligations under Article 2 of the American Convention on Human Rights to adopt domestic legislation to implement its human rights obligations. The invalidation of Uruguay’s Amnesty Law was in line with decisions against amnesty laws in Peru, Chile and Brazil that had been issued over the previous decade.Footnote 24

The Court ordered 13 unique remedies in the Gelman case, which included financial measures, orders to investigate and sanction, guarantees of non-repetition, and measures of satisfaction. As a guarantee of non-repetition, the Inter-American Court ordered Uruguay to ‘guarantee that the Expiry Law [referred to in this article as the ‘Amnesty Law’] … will never again be an impediment to the investigation of the facts and for the identification, and where applicable, punishment of those responsible’.Footnote 25 In other words, Uruguay was being ordered to overturn the Amnesty Law. What was different from the other countries’ cases regarding their amnesty laws was the fact that in Uruguay, the Amnesty Law had been twice upheld in popular referenda. The first failed effort to overturn the law was in 1989 after groups launched an unsuccessful referendum effort immediately following its enactment.Footnote 26 The second was in 2009, just two years prior to the Court’s decision, with 52 per cent voting to uphold the law, and 48 per cent voting to overturn it. While the Court acknowledged the direct democratic procedures, it ruled that this ‘does not automatically or by itself grant legitimacy under International Law’.Footnote 27

Even with the clear mandate from the Court, no one knew whether or how Uruguay would comply with the decision. Overall, in part due to its strong domestic legal system, Uruguay has had the second-lowest number of cases reach the Court of countries within the Organisation of American States that are under the Inter-American Court’s jurisdiction.Footnote 28 In fact, Gelman was the first dictatorship case from Uruguay to reach the Court, despite Uruguay having been under the Court’s jurisdiction for over 20 years at the time. Therefore, there was not much jurisprudential precedent to predict how closely the nation would follow the Court’s recommendations. Previous scholarship has found that states generally comply with remedies like paying monetary reparations and publishing the judgment, but the compliance rate for orders to investigate, prosecute and punish is extremely low.Footnote 29 Additionally, the last democratic referendum on the Amnesty Law had been held just two years prior to the decision, engendering tension about an international court’s imposition on Uruguayan sovereignty and domestic will. The Inter-American Court’s decision was in line with previous jurisprudence that consistently overturned amnesty laws; however, this time it was perceived as doing so through taking a counter-majoritarian position that it had been able to avoid in cases in other countries where the amnesty laws had never been supported by referenda.Footnote 30 Even so, there was real hope about the possibility for trials because of domestic conditions, particularly from victim groups.

Initial Compliance Conditions

In the domestic realm, Uruguay seemed to possess three important facilitating factors to produce compliance: a sympathetic government coalition party in power, individual progressive members of an independent judiciary, and a strong and persistent civil society. First, regarding governmental support, the ruling occurred under second consecutive term of the left-wing coalition of the Frente Amplio (Vázquez 2005–10 and José Mujica 2010–15). The coalition passed a host of progressive legislation such as an affirmative action law, education reform (including increased funding and autonomous cogovernance of the university system), labour regulation and laws that legalised abortion and same-sex marriage, among many other policy efforts.Footnote 31 At the time, Freedom House’s Freedom in the World project ranked Uruguay as one of the ‘freest’ countries in all of Latin America, on a par with Chile and Costa Rica.Footnote 32 Moreover, Vázquez, during his first term in office (2005–10), had pursued and seen some success in using legal loopholes to the Amnesty Law that resulted in the prosecution of figures such as Gregorio Álvarez (2009 conviction) and Juan María Bordaberry (2010 conviction).Footnote 33 Thus, without the constraints of the Amnesty Law, and with both a human rights-friendly executive and a majority in Parliament, it seemed as if Uruguay had governmental support for compliance.Footnote 34

Another factor Uruguay seemed to have in place at the time of the ruling was a progressive and independent judiciary.Footnote 35 As Elin Skaar has argued, in the years after the passage of the Amnesty Law, Uruguayan judges had been more reluctant to invoke international law to challenge impunity as compared to many of their neighbours because of the judiciary’s institutional design, incentive structure and exposure and lack of tradition in incorporating international human rights norms.Footnote 36 Yet, by the time of the Gelman ruling in 2011, there had been a generational change in the judges, with more than half of them appointed after the end of the dictatorship, and many having been sensitised to human rights law as part of their legal training.Footnote 37 These judges now also had the added pressure of responding to international advocacy to comply with the regional court ruling and, as Lessa and Skaar have argued, ‘a heightened sensitivity to international precedent’.Footnote 38 Thus, more progressive judges occupied key positions in the judiciary.

Third, a persistent civil society played a fundamental role in pushing for accountability. Both through the formation of new activist groups and the use of innovative strategies by old and new groups alike, human rights organisations played a major role in reinforcing and strengthening the calls for accountability that capitalised on the Gelman decision. As epitomised by the statement of Óscar Urtasun, a member of the Madres y Familiares de Uruguayos Detenidos – Desaparecidos (Mothers and Relatives of Uruguayan People Detained and Disappeared), the Gelman decision ‘transcends’ the one case, showing that the whole world would be watching countries when they ‘are not doing everything necessary so that those responsible go to jail’.Footnote 39

These domestic conditions were reinforced by strong international momentum, with the Gelman decision occurring during the global justice cascade. In neighbouring Argentina, trials of abuses that had taken place at the Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada (Higher School of Mechanics of the Navy, ESMA) and under the aegis of Operation Condor were under way which centred regional attention on the possibilities of human rights accountability, even decades after the transition to democracy.Footnote 40 While this shift did not indicate that all violators of human rights would be held accountable, the idea that state officials could and would be held accountable was perhaps at a historic high.

The combination of these factors produced cautious optimism among many Uruguayans who had been seeking justice. For some victims, these domestic and international factors were promising indicators of potential success. Indeed, cases that had been ‘archived’ because of the Amnesty Law were reopened and victims filed new cases in court. Several contemporaneous interviews reveal the ways many believed that Gelman would make justice possible in the initial aftermath of the decision. For example, Sandra Pelúa, who worked with Hijos por la Identidad y la Justicia contra Olvido y el Silencio (Children for Identity and Justice against Forgetting and Silence, HIJOS)Footnote 41 and whose father was disappeared in Argentina, said that she believed the decision would ‘open up investigations … one has to hope that things will happen’.Footnote 42 Verónica Mato, also a member of HIJOS, whose father was disappeared in 1982, had her case reopened after the Gelman decision. She expressed cautious optimism that the case ‘can finally be investigated’.Footnote 43 Valentín Enseñat, whose father was disappeared in 1977, explained that Gelman spurred a search for more remains, and challenged the collective acceptance that there was no information on the disappeared. He hoped that the Court’s decision would push the state to offer more information on what happened to the disappeared ‘in a more systematic way’.Footnote 44

According to Ariela Peralta, a lawyer in the case, this was one of the intended goals. She explained that Gelman’s case was an example of human rights groups’ ‘strategic litigation’ to require the state to produce a roadmap for how to address human rights abuses. In the aftermath of the decision, she elaborated that the process ‘opened many doors, mobilised the victims’ organisations themselves, generated debate, discussions, gave arguments for legal action, but also from the State itself, the political system began to move’. She argued that seeing Uruguay condemned internationally generated debates at the political and societal level: ‘it was really an explosion’.Footnote 45

Gabriel Mazzarovich perhaps best encapsulates the perspectives of many after the decision. Mazzarovich had multiple family members, including his father, imprisoned for long periods of the dictatorship, and he himself had been active in various clandestine movements, including the student movement, during this time. The military arrested and tortured him in June 1981 when he was only 16 years old. In an interview in 2012, he explained that despite civil society having fought against impunity for 25 years, the Gelman decision offered ‘new paths for society’. He acknowledged that it would still require hard work from judges and prosecutors ‘who put everything on the line’ to work for prosecutions; from archaeologists working to uncover bodies in the military barracks; and from victims, ‘who are at the centre of everything’ and continue to speak out, denounce and ‘overcome pain’, to work for justice. Yet, despite the obstacles all these people faced, Mazzarovich noted that the judgment offered support for those who had been working so hard within Uruguay for years, and that he could finally see a real opportunity for justice.Footnote 46

Outcomes

At first, this optimism seemed well placed as Uruguay complied with several of the Inter-American Court’s orders, including overturning the Ley de Caducidad.Footnote 47 Indeed, human rights groups put persistent pressure on the government by using the Gelman decision to argue for Parliament to overturn the Amnesty Law.Footnote 48 It was a successful tactic. In June 2011, President Mujica issued Decree no. 323, which repealed key parts of the Amnesty Law. Then, in October 2011, Parliament passed Law no. 18,831, effectively cancelling all the provisions contained in the Ley de Caducidad and eliminating the main barrier to prosecutions as proscribed in the Gelman decision.Footnote 49

However, even as Uruguay initially complied with the Inter-American Court’s rulings, there was concern among legal scholars about the legitimacy of the Court’s invalidation of Uruguay’s Amnesty Law. The Gelman decision followed the Inter-American Court’s jurisprudence on the illegitimacy of amnesty laws, but scholars noted key differences between Uruguay’s Amnesty Law and laws imposed in other Latin American states. As Roberto Gargarella explains, the Inter-American Court did not believe in the ‘democratic legitimacy’ of Uruguay’s law, namely, the two civilian referenda in 1989 and 2009 that voted to uphold the law. In essence, the Court argued that a majority cannot vote on rights that are guaranteed in the American Convention on Human Rights. The Court also referenced the rulings of domestic courts in other countries that placed limits on referenda that restricted the rights of minority groups, like those of same-sex couples and migrants, to bolster its position. Yet, the two referenda created a stark contrast between Uruguay’s amnesty law and those of other countries in the region that were often imposed unilaterally by the military when leaving power, or by civilian governments.Footnote 50 In those circumstances, amnesty laws were almost never voted on or approved by popular referendum.

These nuances of the Court’s decision to overturn Uruguay’s Amnesty Law created opportunities for pushback to arise and allowed government officials to drag their feet on certain measures that would guarantee compliance. Indeed, on 22 February 2013, less than 18 months after the law overturning the Amnesty Law was passed, Uruguay’s Supreme Court of Justice (SCJ) invalidated Articles 2 and 3 of Law no. 18,831.Footnote 51 Displaying an overall conservative position on the issue of the Amnesty Law that had been consistent since the transition back to democratic rule, the SCJ found that the reclassification of dictatorship-era crimes as crimes against humanity was unconstitutional, as Uruguay had not recognised crimes against humanity as illegal until after transitioning to democracy.Footnote 52 Thus, dictatorship-era crimes were classified as common crimes and subject to the statute of limitations, so the window for prosecution was closed.Footnote 53 The ruling effectively meant that the key provisions of the Amnesty Law were brought, as Amnesty International put it, ‘back to life’ and that many gross human rights violations committed under the dictatorship could not be prosecuted.Footnote 54

The Inter-American Court took note of this outcome when it monitored compliance in the Gelman case a month later in March 2013. Interestingly, at the time of the compliance hearing, which took place in February, Uruguay’s actions (Decree no. 323 and Law no. 18,831) were ‘assessed positively by the Inter-American Court, because they were designed to comply with the judgment in the Gelman case’.Footnote 55 However, the final report, published on 20 March 2013, came after the SCJ decision and reflected this rapidly shifting landscape.

In its 2013 Monitoring Report, the Court verified that Uruguay had fully complied with four orders, partially complied with four other orders, and was non-compliant with the remaining five measures. The order to invalidate the Amnesty Law was partially complied with: while Article 1 of Law no. 18,831 did repeal the Amnesty Law, the SCJ’s recent judgment invalidating Articles 2 and 3 ‘constitutes an obstacle to full compliance with the Judgment’.Footnote 56 The Inter-American Court reasoned that the invalidation of Articles 2 and 3 would severely impact the ability of human rights investigations and prosecutions, including in the Gelman case, to move forward because the law ‘appears to have little practical utility if, owing to subsequent court rulings, such crimes are declared expired’.Footnote 57

When the Inter-American Court monitored Uruguay’s compliance again in 2020, it noted that Uruguay had still not fully complied with the order to overturn the Amnesty Law nor, consequently, with the order to investigate, prosecute, and punish those responsible for María Claudia’s forced disappearance. Moreover, Cabildo Abierto, the far-right party that entered the ruling coalition with the Blancos in 2019, has openly pushed for the Amnesty Law to be reinstated. Ultimately, after the initial hope and compliance in 2011, very little progress was made after 2013, and outright backlash was present after 2019. What went wrong?

Compliance Factors: Civil Society, Progressive Judiciary and Executive Will

As previously identified, strong civil society, a progressive judiciary and executive will are all fundamental facilitating factors for compliance.Footnote 58 Based on evidence from the decade after the Gelman ruling, it is clear that Uruguay’s struggling but persistent civil society was the only consistently strong pro-compliance force. Civil society is comprised of diverse groups of victims, families, and human rights groups, many of which had emerged during and immediately after the dictatorship.Footnote 59 As argued below, the progressive judiciary was inconsistently present after 2013, and executive will was only weakly present during the remainder of Mujica’s term as president (which ended in 2015) and Vázquez’s second term (2015–20). By 2019, with the rise and election of the Cabildo Abierto, executive will was in favour of impunity. Table 1 summarises the changes in these factors throughout each period – 2011–12, 2013–18 and 2019–21 – as well as the observed outcome as it relates to compliance.

Table 1. Uruguay: Changes in Compliance Factors, 2011–21

As previously discussed, the initial post-Gelman period is characterised by cautious optimism and movement towards compliance. Contemporaneous interviews from civil society actors demonstrate activists’ hopes and expectation of cases moving forward; this was further buoyed by the executive and legislative actions to overturn the Amnesty Law by the end of 2011. Uruguay’s initial success with compliance during this period demonstrates the importance of all three factors – civil society, judiciary and executive – for achieving a positive outcome. Moreover, we can see the value of both the executive and judiciary in promoting compliance by examining what happened in the latter two periods. As detailed below, the progressive judiciary was first lost in 2013, resulting in the undoing of initial compliance efforts. Even when the judiciary became more progressive, as a result of the SCJ’s personnel shift in 2019, compliance still did not occur, at least in large part because now the executive was opposed. While we cannot observe all possible combinations of these three factors, examining the varying degrees to which each existed across the different time periods, along with different compliance outcomes, allows us to draw conclusions about which one(s) create opportunities for compliance.

The Loss of the Progressive Judiciary: 2013–18

As previously mentioned, the SCJ resurrected aspects of the Amnesty Law when, on 22 February 2013, it overturned parts of Law no. 18,831 (meant to cancel provisions of the original Amnesty Law), finding unconstitutional the reclassification of dictatorship-era crimes as crimes against humanity. However, this was in fact the second major setback experienced by justice advocates: the first occurred the previous week on 13 February when the SCJ informed Mariana Mota, a judge who was one of the strongest champions of human rights trials in the country, of its decision to transfer her from her then-current criminal post to one in the civil jurisdiction.Footnote 60 In 2013, Mota alone had more than 50 cases under investigation on her docket after the flood of cases began to reach the courts. The SCJ announced her transfer without explanation, a practice that Uruguay had utilised in the past when human rights issues reached the court system through creative legal manoeuvring around the Ley de Caducidad.Footnote 61 The difference now was that the Amnesty Law had been overturned, with the express purpose of removing impediments to pursuing justice. Yet, the same tactic of removing judges was employed to prevent cases from moving forward, in violation of the Gelman ruling.Footnote 62 The move resulted in large demonstrations and denunciations, both domestically and internationally.Footnote 63

The loss of a progressive judge presiding over dictatorship-era prosecutions impeded the ability of the judiciary to comply with the ruling, as the prosecutions on Mota’s docket could not proceed without her. Furthermore, as a result of the SCJ’s ruling against Law no. 18,831, other judges were unable to proceed on cases involving dictatorship-era crimes. These judges cited inconsistent rulings by the SCJ, mixed signals from the government, particularly in providing documentation, and lack of access to information as reasons why they could not proceed.Footnote 64 It is hard to know whether this paralysis in the courts resulted from pressure from the military, confusion over how to proceed in the absence of the Ley de Caducidad, or something else entirely. Yet, the result was the same. While civil society remained engaged, particularly in fervent protest against both setbacks, the judiciary as a willing partner for full compliance seemed to dissipate, removing one facilitating factor for compliance.

After 2013, the judiciary largely displayed intransigence in many cases, further stymying efforts for justice. In late 2017, for example, the SCJ issued a ruling that displayed its commitment to upholding the statute of limitations argument. In this trial, a woman from the city of Tacuarembó, known as ‘A.A.’ in court documents, accused the military of illegally detaining and torturing her in 1972 as part of its larger political project. The SCJ, however, responded with a ruling that the violations committed did not constitute crimes against humanity and therefore were subject to statutes of limitations whose expiry dates had already passed. This was only one of multiple cases that received the same decision by the SCJ in this period, demonstrating a continued judicial intransigence on issues of accountability for the dictatorship, despite the Gelman decision.Footnote 65

Even the limited cases that have progressed in the judiciary lacked full compliance with the Gelman decision. In 2017, for instance, a domestic court found five members of the armed forces guilty of the murder of María Claudia Gelman. The ruling was upheld despite two appeals in 2018 and 2020.Footnote 66 While it was significant that the men were held accountable, victim groups expressed dissatisfaction that even this measure of justice still did not satisfy Uruguay’s compliance obligations in the Gelman case. In particular, the conviction was not for the ongoing crime of forced disappearance, nor did it establish intention behind the crime, locate María Claudia’s remains, or establish the full truth about what happened in her disappearance.Footnote 67 Human rights lawyer Pablo Chargoñia also noted that the 2017 conviction itself did not reflect an inflection or change in any way of the broader sense of justice for the crimes committed.Footnote 68 In other words, while the perpetrators of this specific crime had been punished, there was not large-scale accountability.

Slow Reemergence: 2019–21

The latter period of 2019–21 saw some limited advancements from the judicial angle. For example, in 2019, the SCJ rejected an appeal from Arturo Aguirre Percel, one of the military officers found guilty of murdering Gerardo Alter by torture in 1973. He argued that the crime fell outside of the statute of limitations. The SCJ disagreed, arguing that the statute of limitations could not apply when the Ley de Caducidad had been in effect.Footnote 69 As a result, Aguirre Percel was sentenced to 21 years in prison.Footnote 70 This reversal by the SCJ was possible because of a major turnover in personnel on the bench. Three of the five SCJ justices started their terms between 2017 and 2019, evidently with a more pro-human rights view of the interpretation of the statute of limitations for human rights trials. While lawyers appealing cases of convicted military continued to claim the convictions were unconstitutional, the SCJ has grown more strident in rejecting the appeals, solidifying a pro-human rights stance. The SCJ went even further in 2021 when it began to sanction lawyers for continuing to use a strategy that they had already ruled on.Footnote 71

Despite the SCJ’s willingness to reject appeals for convictions of members of the military, the decision from 2013 on Law no. 18,831, finding the reclassification of dictatorship-era crimes as crimes against humanity unconstitutional, still stands. Notably, the convictions being appealed are for murder, not for forced disappearance or other crimes against humanity. While access to justice in some form has no doubt expanded, compliance with the specific orders in the Gelman case remains pending. Unless and until the SCJ’s 2013 decision is reversed, and Law no. 18,831 is reinstated in full, this is unlikely to change.

Declining Executive Will: 2013–18

At the executive level, the Frente Amplio party – despite its control over both the presidency and the Parliament – spent only limited political capital on accountability efforts. After the 2013 Gelman Monitoring Report, President Mujica still had two more years in office. His presidency was characterised by a flurry of progressive legislation that raised his profile internationally.Footnote 72 Yet, after a public apology and installation of a placa de memoria, both of which had been ordered by the Inter-American Court, Mujica made little progress on accountability issues. Most glaringly, he refused to counter the decisions made to transfer Mota or overturn parts of Law no. 18,831. While himself a victim of the nation’s dictatorship – he suffered 13 years of imprisonment and torture, most of it in solitary confinement – focusing on accountability would also potentially leave him vulnerable to discussions about his participation in the Tupamaros, a leftist guerrilla group. Throughout Southern Cone transitions back to democratic rule, the military and those on the Right have overstated and exaggerated claims that equate state violence and the revolutionary actions of leftist guerrilla groups. Yet, Mujica’s silence was potentially a political calculation to allow him to focus on passing progressive legislation without being dragged into accountability politics and quite possibly opening himself up to criticism that might undermine his larger agenda.Footnote 73

After years of inaction on Mujica’s part, Vázquez was elected to his second non-consecutive term and inaugurated in March 2015. Initially, many activists were optimistic about judicial possibilities with Vázquez’s return to government, especially since he had made advances in accountability during his first term in office and would now take the oath without the official constraints of the Amnesty Law. On assuming office again, he launched a Grupo de Trabajo de Verdad y Justicia (Working Group on Truth and Justice).Footnote 74 This prominent body was tasked with gathering information on past crimes, as well as advancing trials and reparations. Comprised of well-known and well-regarded figures across the country, the move was seen as an important political step and commitment by the Vázquez government to advance the cause of accountability.Footnote 75 It seemed to recommit the executive branch to measures of compliance after two years of stagnation.

Vázquez’s Working Group on Truth and Justice, however, proved largely symbolic, demonstrating the precarity of executive political will as a facilitating factor for compliance. The Working Group made little progress in its stated goal of proceeding with trials. Amnesty International’s 2017/18 report on Uruguay noted that the body had ‘not achieved concrete results’.Footnote 76 Even the head of the Working Group, Felipe Michelini, admitted that while initial expectations were very high, he ‘always was pessimistic’ about the possibilities for advancing trials due to the length of time that had passed since the violations had occurred and the ‘mafia agreement/pact among perpetrators not to talk’ about what happened.Footnote 77 These shortcomings were further confirmed within Uruguay when the Madres y Familiares de Uruguayos Detenidos – Desaparecidos decided to leave the Working Group and to withdraw their support and cooperation. In a press release, the organisation expressed its frustration with the slow pace of the Working Group’s attempts to advance its objectives and claimed that its stagnation had yielded no new information or advances towards retributive justice.Footnote 78 Instead, the organisation committed itself to working for justice through other means. Vázquez’s government and Parliament, believing that they had done their part by setting up the Working Group, displayed little additional political will to overcome its inadequacies in the face of judicial obstinacy.Footnote 79 By August 2019, the executive had dissolved the group and transferred some of its mandates to the Institución Nacional de Derechos Humanos y Defensoría del Pueblo (National Human Rights Institution and Ombudsman, INDDHH).Footnote 80

Despite these various challenges, the most positive action to occur during this period was under the auspices of Law no. 19,550, the ‘Creación de Fiscalía Especializada en Crímenes de Lesa Humanidad’ (‘Creation of the Office of the Special Prosecutor for Crimes against Humanity’), under which Vázquez and Parliament helped set up the Office of the Special Prosecutor, aimed specifically at advancing trials. It was established on 22 February 2018, and began collecting evidence to file cases. Yet, by the time Vázquez left office, it was unclear whether the Office would produce any results, as even the cases it started to work on ran into defendant petitions of unconstitutionality based on the statute of limitations.

Opposed Executive Branch: 2019–21

If these were the conditions under a leftist Frente Amplio government, Luis Lacalle Pou’s election as a candidate from the centre–right Blanco Party offered no cause for optimism. The 2019 election was perhaps most noteworthy for the emergence of a new political party, Cabildo Abierto, led by Guido Manini Ríos. Manini Ríos is the former chief commander of the armed forces and is open in his praise of the former dictatorship. Vázquez had dismissed him from his position in the military after he criticised even the limited steps the judiciary had taken to pursue accountability for the dictatorship’s crimes.Footnote 81Furthermore, he openly campaigned to have the Ley de Caducidad formally reinstated. Several candidates who ran for office on the party’s ticket were also former members of the Juventud Uruguaya de Pie (Uruguayan Youth at Attention), a far-right extremist group with paramilitary connections that operated under the military government.Footnote 82 In order to form a governing coalition, Lacalle Pou and the Blancos linked with the Cabildo Abierto after the election. While Lacalle Pou was perhaps never a strong advocate for the pursuit of justice, the political composition of the new governing coalition meant that instead of being neutral on these issues, he was bound to entertain the far Right’s attempts to reverse any progress. Indeed, once in office, the Cabildo Abierto continued to push for efforts to resurrect the Amnesty Law, as well as introduce other legislation to further impunity; for example, under the guise of addressing overcrowding in prisons during COVID-19, all convicted persons over the age of 65 would be granted house arrest. If passed, the law would immediately impact the two-dozen former military and civilian personnel who have been convicted of crimes committed during the dictatorship.Footnote 83 As of publication, parts of the Cabildo Abierto are still pushing for the measure.Footnote 84

The increased backlash is perhaps most evident in Uruguay’s actions during the hearings and subsequent aftermath of a second dictatorship-era case, Maidanik et al. v. Uruguay, which the Inter-American Court took up exactly ten years after the Gelman decision.Footnote 85 During the 2021 hearings of this case, Uruguay actually argued that that the Court should not compel further action because it was already in compliance with its international human rights obligations. This argument is in clear contradiction with the 2020 Monitoring Report in the Gelman case.Footnote 86 Uruguay’s antagonistic position indicates a shift from the 2010 hearings in Gelman (where there was no contestation) and is a window into Uruguay’s perspective on its commitment to only particular international obligations. When the Court issued a judgment in the Maidanik case in December 2021, Uruguay’s response to the decision finding it responsible for dictatorship-era crimes was more stilted than its response to Gelman. Although prosecutions after the Gelman case were limited, Uruguay did stage a public and highly praised ceremony accepting responsibility for the crimes committed against Gelman and his family, at which President Mujica gave a formal acknowledgement and apology. A similar ceremony was ordered in the Maidanik ruling, but the government’s response exemplifies its resistance to accountability. President Lacalle Pou refused to attend the ceremony and sent his vice-president instead, to the consternation of the victims and their families.Footnote 87 Actions by Uruguay’s executive branch in relation to both the Maidanik hearings and its aftermath thus demonstrate how far executive will declined relative to 2011.

The Persistence of Civil Society

While a progressive judiciary and executive will have proved to be inconsistent variables, civil society has remained constant.Footnote 88 In Uruguay, the civil society groups working for human rights include both historic groups that were formed either during or immediately following the dictatorship, as well as newer rights groups that emerged in subsequent decades. For example, Madres y Familiares de Uruguayos Detenidos – Desaparecidos was founded by mothers and family members during the height of the dictatorship and have continued to push for accountability ever since the transition back to democratic rule.Footnote 89 Others such as HIJOS are comprised of children of victims who founded them to seek justice for their parents. The power of these multigenerational groups has been a vital and consistent component during the entire post-Gelman decision period.

In the immediate aftermath of the decision, these groups led the charge to push for its implementation. Supported by legal groups such as the Instituto de Estudios Legales y Sociales del Uruguay (Uruguayan Legal and Social Study Institute, IELSUR), they refiled or ‘unarchived’ cases. CEJIL, which had litigated the Gelman case, also worked with international groups like the New Media Advocacy Project to launch a publicity campaign and push for implementation. Following the 2013 reversals, these groups led protests on the streets and online. They also continued to raise awareness and push for implementation in spite of the judicial and executive setbacks. For example, in October 2017, several human rights groups and unions launched a campaign on social media and in the streets to highlight judicial delays and to push national courts to proceed with trials. Under the hashtags #26Oct and #nohayderecho, the online campaign was accompanied by a march in Montevideo that coincided with the opening of the 165th Regular Session of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which was taking place there for the first time.Footnote 90 Powerful testimonies by victims about their experiences of torture and political imprisonment were broadcast across Twitter and Facebook. This new media campaign showed men and women sitting in or around the former detention centres, a powerful visual message about the physical location of the crimes and the enduring pain they had caused.Footnote 91 Alongside gaining international attention for the Commission proceedings, civil society groups hoped to pressure Vázquez into making further commitments to justice.

Civil society’s work was hampered by backlash against justice initiatives from certain segments of the population, as evidenced by the attacks they had to endure. First, in 2016, the offices of the Grupo de Investigación en Antropología Forense (Forensic Anthropology Investigation Group, GIAF) were broken into, and evidence they had uncovered regarding crimes of the dictatorship was stolen.Footnote 92 Then, in March 2017, death threats were made against authorities and human rights defenders who had been working to advance the possibility of trials, referencing the recent suicide of General Pedro Barneix, who killed himself just before he was to be arrested for killing Aldo Perrini during a torture session in 1974.Footnote 93 The anonymous death threat stated that ‘the suicide of General Pedro Barneix will not remain unpunished … no more suicides of unjust prosecutions will be accepted. From now on, for every suicide, we will kill three people selected at random from the following list.’Footnote 94 The list included the Uruguayan defence minister, a court prosecutor, the director of the INDDHH, human rights lawyers and foreign scholars. Human rights groups condemned the note, seeing the letter as a clear attempt to thwart efforts to continue pushing for trials. However, the government did not respond publicly to the note and never provided any information regarding the status of investigations into the source of the threats, even as many suspect that the emails came from former members of the military and police.Footnote 95 Further evidence of backlash was evident when two different memorials dedicated to honour victims of the military dictatorship were vandalised in 2018, which further contributed to a sense of growing impunity.Footnote 96

Civil society, however, has continued to push for accountability, even in light of the backlash. The annual ‘Marcha del Silencio’ on 26 May continues to be a massive event, with the inauguration of several new locations in 2018, including some in the interior of the country and not just in the capital.Footnote 97 During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, the march took place virtually, with massive participation from across the world.Footnote 98 The groups have also continued to push for the inauguration of new memorials, to make visible the memory of those that were disappeared.Footnote 99 Various groups have also responded with strong condemnation of the continued backlash and political denunciations, demonstrating constant vigilance in the face of attack. As such, throughout the ten-year time horizon after the Gelman decision, human rights actors demonstrated the most consistent pressure for accountability in both public as well as judicial spheres. While scholars are increasingly recognising the importance of civil society actors in achieving compliance with the Inter-American Human Rights system, it is, on its own, an insufficient factor.Footnote 100

Conclusion

Uruguay has emerged from its period of dictatorship as one of the strongest democracies in South America. Yet, it has struggled on issues of criminal accountability and even fallen behind many of its neighbours in the victims’ quest for justice. The Ley de Caducidad meant that, for much of the first two and a half decades after the country’s transition back to democratic rule, cases that reached a successful conclusion did so only through creative legal manoeuvring and loopholes. The Amnesty Law’s de facto endurance in the first ten years after the official repeal, due to the judiciary’s invocation of the statute of limitations and other impediments, led Uruguayans to look abroad for opportunities to pursue justice – including Argentina (Operation Condor trials), Italy (Troccoli case), and, of course, through the Inter-American Human Rights System.Footnote 101

Some activists hoped pressure from abroad – the sight of Uruguayans being tried in foreign courts as well as the recommendations of the Inter-American system – would compel domestic action.Footnote 102 Indeed, civil society actors used these international cases to advocate for movement from the judiciary and, in recent years, particularly strong advocacy has emerged from children of victims and those who grew up in shadow of the dictatorship’s legacy. Yet, even in the aftermath of the official repeal of the Amnesty Law, the three facilitating factors that would offer windows of opportunity for compliance have not been consistently present: although civil society has endured, despite threats to the lives and work of activists, neither the executive nor the judiciary have been reliable partners or actors in compliance efforts.

Consequently, the years following the 2013 Gelman Monitoring Report showed sustained activism by civil society but no substantial progress in terms of compliance. The lack of compliance can be attributed to continued obstruction or lack of political will by the judicial and executive branches, which was a recurring theme in the Inter-American Court’s 2020 Monitoring Report on Gelman. The Court was sceptical of the judiciary’s willingness to prosecute dictatorship-era crimes, noting both the limits of the 2017 murder conviction in the Gelman case as well as the continued imposition of the statute of limitations to block further prosecutions. Furthermore, the Court questioned the executive’s commitment to human rights training programmes and protocols related to the identification of remains.Footnote 103 Overall, Uruguay’s continued impunity during this period further underscored the importance of political will and a progressive judiciary, as well as the insufficiency of a strong civil society alone to achieve compliance.

Uruguay’s experience with implementing the compliance orders in Gelman demonstrates the fundamental challenges of compliance, particularly with initiating trials, even in established democracies. The important conclusion here is that neither political party was particularly eager to advance human rights justice initiatives. Even the leftist coalition of the Frente Amplio struggled to move trials forward substantially. Both Mujica and Vázquez, the two Frente Amplio presidents, used their political will to advance other progressive priorities, perhaps at the expense of justice initiatives. It was easier for them to make formal apologies, hang plaques, and create institutions (even if they were understaffed and under-resourced). They proved largely unwilling, however, to spend the political capital to move forward trials that would comply with the Inter-American Court’s order to investigate and punish offenders.Footnote 104

It is also notable that backlash against international justice has grown over time, rather than decreased. There is an emerging tension within Uruguay, where certain sectors of the citizenry fail to look to the Inter-American Court for human rights guidance, and instead see its decisions as a violation of state sovereignty. Indeed, as early as 2012, just a year after the Gelman decision, Pablo Chargoñia argued that various politicians had begun to discredit or ignore the Court, claiming a violation of sovereignty or disputing the Court’s authority, even though Uruguay itself had committed to the Court’s jurisdiction.Footnote 105 This resistance grew over time from various political sectors and with the creation of new political parties. Uruguay’s more hostile response to a subsequent dictatorship-era case, Maidanik et al., decided in 2021, reflects the increased backlash against the Court.

Our research demonstrates the importance of examining a longer timeframe for compliance. We have analysed the non-linearity of the compliance process in Uruguay’s case, replete with backsliding. The factors needed to implement compliance orders do not remain constant over time.Footnote 106 Although compliance is often thought of as a binary variable, our analysis reveals that whether Uruguay complied or was likely to comply depends a great deal on when one looks. In December 2011, Uruguay was largely in compliance with the ruling and seemed to be moving forward, with cautious optimism from many victim groups, on judicial accountability. However, just 15 months later, much of that forward momentum and progress was stymied and undone. By 2021, the chances of full compliance with the Gelman order on investigation, prosecution and punishment seemed very bleak, given the position of the executive.

While our focus in this article has been largely on Uruguay and the Gelman case, we believe it offers lessons for others studying compliance in other contexts as well. First, we demonstrate the importance of case studies for compliance outcomes, especially over longer periods of time. While it may be impossible to do this for every case or ordered remedy, choosing to study the implementation of particularly difficult remedies may offer important insights into facilitating factors for compliance that could then be tested more broadly. Second, and relatedly, we do not believe that the facilitating factors we have identified are unique to Uruguay. Future research might examine the presence (or absence) of these factors in other countries that have similarly received orders to overturn amnesty laws, like El Salvador (which overturned its law in 2016 after three cases at the Inter-American Court) and Brazil (which has yet to overturn its law).

Our analysis supports the idea that a strong civil society, a progressive judiciary, and a willing executive are all needed for some of the more difficult measures of compliance to be implemented. After ten years of changing domestic conditions during which activists have attempted and failed to compel compliance the Gelman decision, there is even less hope for compliance in the Maidanik case. The lack of international attention directed at Maidanik means less pressure to compel an even less sympathetic government into action, casting doubt on the extent to which Uruguay will comply with all the aspects of the Inter-American Court’s new decision. Thus, while Gelman and Maidanik signalled the strength of the Court’s jurisprudence with respect to human rights issues, Uruguay has often fallen in many respects outside of ‘the justice cascade’ especially with respect to judicial accountability, leaving victims still searching for verdad y justicia.