Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 80 per cent of those with disabling hearing loss live in low- to middle-income countries.1 Yet, it is in these same settings that ear disease and hearing loss frequently go unrecognised or untreated. There can be a multitude of reasons for this. At state, regional or local levels, there may be a lack of awareness of the prevalence or consequences of ear disease,Reference Mackenzie and Smith2 or insufficient prioritisation against other health needs.Reference Wilson, Tucci, Merson and O'Donoghue3, 4 Amongst health workers, knowledge may be lacking on how to diagnose, prevent or treat such disease, or there may insufficient financial or human resources to tackle the problem.4 Lack of infrastructure or logistical challenges may make the delivery of ear and hearing care problematic. It is important to recognise that these issues can also affect disadvantaged or remote communities in affluent countries. In particular, indigenous communities such as Aboriginal Australians, Native Americans and Arctic populations suffer a high burden of chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM), for reasons that are debated.Reference Bhutta5

A number of strategies and programmes have been suggested and/or trialled to address ear and hearing health in remote or resource-limited settings, and I have worked with several different models in different countries. This article aimed to describe an approach to developing the delivery of ear and health care to a community, and to document some existing models of care, with perceived advantages and disadvantages of these models, and (where possible) evidence of their effectiveness or ineffectiveness.

Unfortunately, there are very few ear or hearing service delivery programmes that have reported relevant outcomes, although that is also true of service delivery programmes in other medical specialties.Reference McDonnell, Wilson and Goodacre6 The reasons for this are multifactorial. Funding for a programme may come from a source that does not require such reporting (giving little incentive to collect such data). Data collection systems may not be robust (especially if programmes were not set up for prospective data capture). Alternatively, there may not be the time or expertise to collect such data (making data incomplete or inaccurate). Even where outcomes are reported, they may not be the most relevant: for example, outcomes may report success in terms of the number of patients undergoing tympanoplasty, whereas a programme of intensive primary ear care may have prevented some of those patients attending surgery in the first place, and may have been more cost-effective. In addition, it seems fair to assume that there is a publication bias, whereby only interventions and programmes that have been successful will voluntarily report on this, even though we can learn as much from failures as from successes.

Global infrastructure and personnel

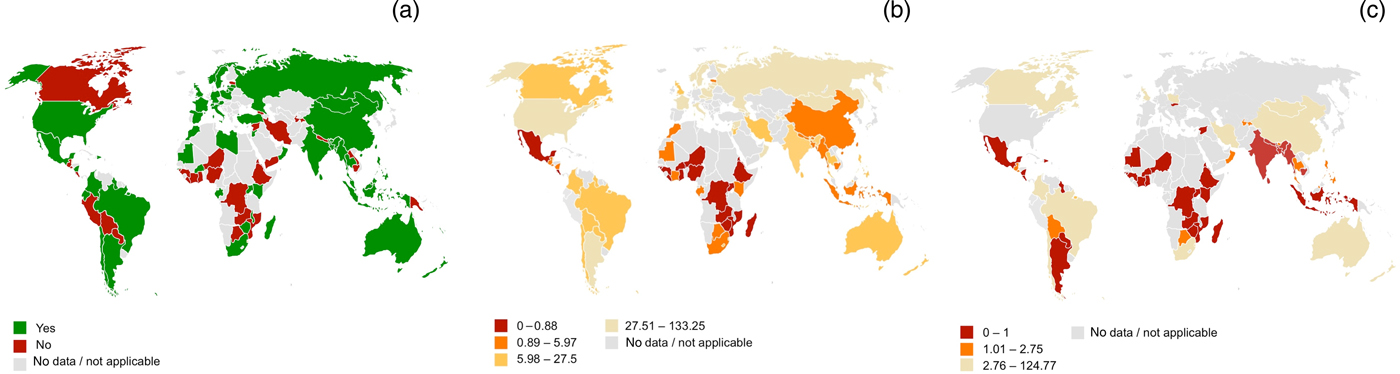

In 2013, the WHO undertook a worldwide survey (through its regional offices) of national self-reported capacity for the delivery of ear and hearing services.4 Although the response rate to this survey was only 49 per cent, the results do present a rather bleak view of the infrastructure and personnel for delivering such services in many low- to middle-income countries (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Global infrastructure for delivery of ear and hearing care based upon the World Health Organization survey: (a) presence of a national plan for ear and hearing care (2012), (b) ENT specialists per million population, and (c) audiologists per million population.4

At state level, in 2013, an estimated 40 per cent of low- to middle-income countries had a national strategy for ear and hearing care (Figure 1a), and this was usually partially or wholly funded by government, and was primarily the responsibility of the ministry of health.4 Most countries that did not have a plan cited other health priorities, or a lack of financial or human resources, as the main reasons why such a plan did not exist.

With regard to human resources, expert opinion is that there should be at least 1 ENT specialist per 500 000 people and 1 per tertiary hospital.7 Although this proportion of ENT specialists is available in many low- to middle-income countries (Figure 1b), in Africa the majority of countries reported less than one ENT specialist per million population.4 Within Australia, there is evidence that children in remote areas wait longer to get hearing tests or ENT services, despite a greater burden of disease.Reference Gunasekera, Morris, Daniels, Couzos and Craig8

For audiologists, the limited available data suggest even fewer personnel, with only 1 of 19 low-income countries reporting the availability of more than 1 audiologist per 1 million population (Figure 1c).4 Some low- to middle-income countries have no audiologist at all.9 Similarly, very few low- to middle-income countries have speech therapists.4 In 2004, the WHO estimated that global production of hearing aids met less than 3 per cent of the needs in low- to middle-income countries.10

Programmes for the education of ENT specialists and audiologists in low- to middle-income countries are also patchy, and in some countries non-existent.4 Where education programmes do exist, their quality will vary, and rarely if ever match the level of training found in high-income countries. My experience from many low- to middle-income countries is that doctors who have completed the local ENT training programme are nevertheless unable to perform tympanoplasty or mastoidectomy. A survey undertaken in Nigeria in 2013 found that only 3 of 17 ENT centres had the equipment and expertise to perform mastoid surgery.Reference Orji11 Many countries have no such centres. Training medical assistants to perform tympanoplasty was considered one way to counter the lack of ENT surgeons (non-surgeons deliver surgical care in many countriesReference Hoyler, Hagander, Gillies, Riviello, Chu and Bergstrom12), but trials of this were reported to be unsatisfactory.7 There is, however, renewed interest in this approach.Reference Strachan13

There have been no systematic assessments of the equipment available to assist in diagnosing or treating ear disease, but I have seen units that may not have a single otoscope, let alone an audiometer. For otological surgery, the set-up costs are significant, requiring microscopes, drills and specialised ear instruments. It may be difficult for a healthcare facility to justify such investment, particularly if local staff members are unable to perform otological procedures. Hence, external help is often needed in initiating specialist services, particularly in surgery.

An approach to initiating new services

When initiating a new service for ear and hearing care, I suggest a systematic approach in evaluating what is possible and achievable. In particular, it is usually very difficult, if not impossible, to initiate a new model of care without engaging local communities and/or health workers, and without using some existing infrastructure.

The approach taken will of course vary with the aims of a particular project or programme. Potential aims may include: (1) evaluating the prevalence of ear and hearing diseases in a community (if this is not already known); (2) educating community or healthcare workers regarding ear and hearing disorders and their treatment; (3) providing medical treatment of ear diseases such as CSOM; (4) providing hearing aids; and (5) surgical treatment of CSOM, including cholesteatoma. Programmes may of course include several of these aims, and indeed aims may become more or less ambitious as things develop.

In order to derive meaningful and sustainable change, any intervention should contribute to a health system's strengthening approach.Reference Kim, Farmer and Porter14 As such, I suggest that at the initiation or change of any project or programme, those leading the project first consider the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the proposed project (a ‘SWOT’ analysis). Such an analysis can and should be informed by an assessment of the community being served, and an evaluation of current and future assets, as detailed below.

Community assessment

Clark has suggested a framework for community assessment based upon six domains (Table 1),Reference Clark15 and I find this a useful approach.

Table 1. The domains of Clark's model of community assessmentReference Clark15

The biophysical domain relates to community demographics. What is the size of the target population? What is the age structure? Are there ethnic variations relevant to ear and hearing health? What is the actual or estimated prevalence of hearing loss or ear disease?

The psychological domain evaluates how a community functions in its relations within the community and with those external to the community. Are there significant events or conflicts in a community to be aware of? What are the community's previous experiences of external healthcare providers?

The physical environment domain includes an assessment of whether the community is rural or urban, the topography, the climate, and road or other transport infrastructure. It is also worth evaluating electricity supply and reliability (is an independent generator needed?), and access to potable water. Some medical equipment is fragile and at risk if transported across undulating roads, including equipment with delicate electrical circuits and microscope lenses. If working in an environment without air conditioning or heating, extremes in the environmental temperature can make working conditions unpleasant, and potentially make operating unsafe for patients under general anaesthesia where normal thermoregulatory function is lost.Reference Sessler16 Humidity is also important; condensation can develop on electrical equipment (leading to malfunction or short-circuiting) and on microscope lenses, and rust becomes much more likely once humidity is above 60 per cent.

The socio-cultural domain includes attitudes, beliefs and knowledge within a community. In many low- to middle-income countries, these differ significantly from Western ideas, including those concerning health and disease. For example, in Australian Aboriginal communities, health may be interpreted in terms of the health of the community rather than the health of the individual, and may also be seen as health status at the current time, disregarding pre-existing chronic disease.Reference Smith and Smith17 Hence, a patient who currently has a dry ear, yet has suffered from years of frequent intermittent ear discharge due to CSOM may regard themselves as healthy and not in need of medical care. A report from India found that only 30 per cent of patients with CSOM knew that a perforation of the tympanic membrane was associated with disease, and very few were aware that CSOM could be life-threatening.Reference Chandrashekharayya, Kavitha, Handi, Khavasi, Doddmani and Riyas18

There can be other differing beliefs about ear and hearing health. If a child is born deaf, it may be interpreted as a punishment from god. In a study from South Africa, 57 per cent of mothers held superstitious beliefs about the cause of hearing loss in their child,Reference Swanepoel and Almec19 and in Nigeria there are reports of altered maternal-child bonding in deaf children.Reference Togonu-Bickersteth and Odebiyi20 Others may not realise that a child who is deaf usually has normal intelligence. It may not always be easy to get individuals to ‘buy in’ to treatment: in Lagos (Nigeria), 84 per cent of mothers were supportive of fitting hearing aids to their deaf child,Reference Olusanya, Luxon and Wirz21 but in Karnataka (India) that figure was only 54 per cent.Reference Ravi, Yerraguntla, Gunjawate, Rajashekhar, Lewis and Guddattu22 Socio-cultural factors can affect others too: in a study from Turkey, a lack of social support from the community for the mother of a deaf child was associated with significant risk of depression in the mother.Reference Sipal and Sayin23 In many countries, deaf people are marginalised and disempowered; for example, they may be denied education or voting rights, and sign language may be repressed.Reference Earth24

It is also important to recognise that socio-cultural differences lead to prevalent use of traditional medicine in some communities. Many traditional healers in South Africa believe in superstitious causes for hearing loss and offer treatments accordingly.Reference de Andrade and Ross25 Otorrhoea may be treated with topical therapies, including oil or honey in Nigeria,Reference Lasisi and Ajuwon26 or leaf paste, oils or urine in Nepal.Reference Poole, Skilton, Martin and Smith27 Widespread use of home remedies or traditional medicine for otorrhoea has also been documented in India.Reference Chandrashekharayya, Kavitha, Handi, Khavasi, Doddmani and Riyas18, Reference Dosemane, Ganapathi and Kanthila28 These traditional therapies are not of proven efficacy. However, people may use them because of their personal views on disease causation, and because of lack of access to Western medicine (due, for example, to a lack of local facilities, or an inability to pay for such services). Some communities also fear hospitals as they are seen as places where people go to die, and when community members delay going to hospital until they are moribund, that prophecy may actually become true.

The behavioural domain relates to the behaviours within a community (which also relates to socio-cultural beliefs). For example, behaviour towards noise-induced hearing loss may relate to norms at the workplace. Studies from Malaysia showed that many workers in a sawmill or quarry had a nonchalant attitude towards noise exposure, possibly due to a lack of knowledge of the potential long-term consequences.Reference Rus, Daud, Musa and Naing29, Reference Ismail, Daud, Ismail and Abdullah30 The behaviour domain also includes understanding the methods for communication in a community, which could be exploited for health purposes. In many low- to middle-income countries, community awareness of health services (and their reputation) is by word of mouth. However, community and local radio has also been used to relay messages about health.31 In addition, with the increasing uptake of social media (including in low- to middle-income countries), internet-based communication platforms are increasingly being used.Reference Moorhead, Hazlett, Harrison, Carroll, Irwin and Hoving32 It is noteworthy that, in general, the deaf community experiences additional barriers in accessing healthcare because of communication difficulties.Reference Kuenburg, Fellinger and Fellinger33

Finally, the health system domain includes an understanding of existing healthcare infrastructure, its utilisation by different sections of the community, and how it is financed. Often in delivering ear and hearing care, it is productive to partner with an existing facility, such as a local health centre, as this enables shared physical and human resources, including possibilities for continuity of care. It is important to also recognise and explore existing traditional medicine systems. My opinion is that it is more productive to work alongside traditional medicine rather than oppose it. If Western medical techniques prove to be of greater efficacy, their reputation and popularity in the community will rapidly grow.

Asset mapping and acquisition

Asset mapping should include finances, and physical and human resources. Physical resources may include items such as medical equipment, buildings and vehicles. Human resources may include trained medical staff, health workers needing to be trained and administrative staff.

Procuring physical assets will depend upon the maturity of local infrastructure. Often specialised medical equipment will have to be imported. Sources for this may include solicited donations from manufacturers, or used equipment from existing healthcare providers in affluent countries (but be wary of well-meaning individuals donating equipment that is dysfunctional or obsoleteReference Diaconu, Chen, Cummins, Jimenez Moyao, Manaseki-Holland and Lilford34). There are also a number of commercial suppliers of used medical equipment (e.g. www.dotmed.com or www.ebay.com online marketplaces). My experience is that good quality used equipment is often better value than new equipment; for example, a 20-year-old Zeiss or Olympus microscope often has better lenses and superior longevity than a new microscope from a budget manufacturer for the same price. For otoscopes, there are low-cost simple otoscopes such as Arclight™ devices, but it is also worth considering video-otoscopes that connect to a computer or devices that fit onto smartphones (e.g. Cupris® or CellScope® devices). The latter carry additional advantages for data capture, health education and telehealth possibilities. Specialised surgical consumables, such as drill burrs and bismuth iodoform paraffin paste (‘BIPP’) packing, can prove difficult to source.

Funding may be available from local healthcare funds (and this should be encouraged), but in low- to middle-income countries, new projects often rely on charitable donations. Organisations that can be approached include those that fund global health initiatives, religious groups or individual benefactors.

Which diseases to treat

Which diseases are treated will depend upon the aim, budget, disease burden and capacity of the project. Primary ear care is easier to deliver with minimal equipment and basic staff training, whereas surgical care requires more input.

In a remote area of Tamil Nadu, India, CSOM was the main disease seen in an ear clinic.Reference Emerson, Job and Abraham35 My experience is also that CSOM is a significant reason for consultation in such settings. Economic analyses also suggest that CSOM treatment is a highly cost-effective intervention,Reference Baltussen and Smith36 and should be prioritised. With improved life-expectancy, presbyacusis is also becoming more prevalent. The ideal service should therefore include (as a minimum) adult and paediatric audiology, hearing aid fitting, and tympanoplasty surgery or mastoidectomy. It may take time to provide all these services.

Reports from low-resource settings suggest that the fitting of hearing aids, even if suboptimal, can provide user-reported benefits at a similar level to that seen in well-resourced settings.Reference Pienaar, Stearn and Swanepoel de37, Reference Olusanya38

In terms of surgery, it is possible to perform many cases of adult tympanoplasty with only a microscope or endoscopeReference Clark39 and local anaesthesia, but mastoidectomy requires more equipment and either sedation or general anaesthetic.

There is interest in delivering cochlear implantation in low- to middle-income countries. Cochlear implant programmes exist, for example, in South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Paraguay and Venezuela.Reference Emmett, Tucci, Bento, Garcia, Juman and Chiossone-Kerdel40, Reference Emmett, Tucci, Smith, Macharia, Ndegwa and Nakku41 Some caution is required, as the cost of setting up an implant programme is substantial, and requires long-range planning and support. A cochlear implant programme may nevertheless prove cost-effective,Reference Saunders, Francis and Skarzynski42 but in many circumstances, deaf education programmes may be even more so.Reference Emmett, Tucci, Bento, Garcia, Juman and Chiossone-Kerdel40, Reference Emmett, Tucci, Smith, Macharia, Ndegwa and Nakku41, Reference Saunders, Barrs, Gong, Wilson, Mojica and Tucci43 Success may also be less than in high-income settings: in 2015, Brazil implanted 1200 children per annum, but reported 11 per cent non-use,Reference Emmett, Tucci, Bento, Garcia, Juman and Chiossone-Kerdel40 compared to 2–3 per cent non-use in the UK.Reference Ray, Wright, Fielden, Cooper, Donaldson and Proops44, Reference Archbold, Nikolopoulos and Lloyd-Richmond45

Challenges in resource-constrained environments

There can be challenges particular to low- to middle-income countries. There are the problems of infrastructure that have been alluded to above, including inconsistency of electrical or water supplies, and difficulties in acquiring specialised medical equipment. It is also wise to be aware of some of the past errors that have been made in delivering ‘humanitarian’ medical care, including failing to match technology to local needs and abilities, failing to co-operate with existing organisations, and not having a sustainable long-term plan.Reference Welling, Ryan, Burris and Rich46

In terms of clinical delivery of care, disease is often advanced at presentation. This is probably due to a number of factors: a lack of access to care (particularly amongst the poorReference Peters, Garg, Bloom, Walker, Brieger and Rahman47), a lack of understanding of disease and treatment options, and low prioritisation by the patient against other health or welfare needs. A medical opinion had been sought by fewer than a third of people with ear symptoms in Nepal,Reference Little, Bridges, Guragain, Friedman, Prasad and Weir48 and only 9 per cent of hearing-impaired children in Nigeria.Reference Ogunkeyede, Adebola, Salman and Lasisi49 Our experience in low- to middle-income countries is also that some patients will suffer with poor hearing and a discharging ear for years, and only present when there is a complication such as a mastoid fistula or mastoid abscess. With such advanced disease, surgeons often need to perform difficult operations with suboptimal equipment. With advanced disease, success may be lower; for example, there is evidence that a long duration of otorrhoea is associated with lower treatment success in CSOM cases.Reference Mushi, Mwalutende, Gilyoma, Chalya, Seni and Mirambo50, Reference Orji, Dike and Oji51

Another challenge to delivering care in remote or resource-constrained settings is the fact that care can be fragmented in comparison to health systems in high-income or urban settings. Although ear care can be delivered largely independent of other health services, continuity of care and follow up of patients can be an issue, particularly for a visiting service, or if the patient is from a setting remote to the point of care. This will necessitate co-ordination with existing local health services, and training of local staff.

A final challenge relates to recruiting and maintaining staff. There are two common options for staffing a service: using externally sourced volunteers or using locally employed staff (many programmes in low- to middle-income countries use a combination of the two). External volunteers can often be found, and the majority will be motivated and competent. However, there can be the occasional volunteer who is not up to the job, and perhaps even comes with the wrong attitude – thinking that during their visit they can practise surgery on patients in low- to middle-income countries without necessarily providing the highest standards of care. That can be difficult to deal with. The other problem is that if volunteers are used more or less exclusively, there will be no capacity for development in local staff, which is not a good model for the long-term. In contrast, using local staff does build capacity, and potential sustainability and longevity of a service, but it takes a lot of time and commitment to train, particularly to deliver surgical care. In addition, local staff members working for a charitable or public service are usually paid at the lower rate for health workers. Because private healthcare is growing in many low- to middle-income countries,Reference Pettigrew and Mathauer52 there is a risk that local low-paid staff will gain training and then leave to work in the private sector. Allowing parallel public and private operating (dual practice) may be an option to consider.Reference Socha and Bech53

There are a number of charities that provide ear care in low- to middle-income countries using volunteers, some of which are listed in Table 2. Many of these charities aim to develop local staff alongside ear missions, but provide little evidence that such aims have been achieved. It can be difficult to provide high-quality training through intermittent visits. I have led a successful in-country surgical training programme in Cambodia, where training was provided over several months by a visiting fellow, with demonstrable quantitative and qualitative educational outcomes.Reference Smith, Sokdavy, Sothea, Pastrana, Ali and Huins54

Table 2. Examples of charitable organisations providing ear and hearing outreach services

Public health and national initiatives

Public health and national level measures are an important component in the delivery of ear and hearing care, although there is little evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of such interventions.

The WHO estimates that around 60 per cent of childhood hearing loss could be prevented through preventative measures, and up to 75 per cent in low- to middle-income countries.55 Suggested preventative strategies include: (1) immunisation to stop congenital rubella, mumps, measles, meningitis and otitis media; (2) better perinatal care to reduce birth complications, prematurity and low birth weight; and (3) reduced use of ototoxic medication.

The WHO also publishes guidance directed towards government or other national bodies, and provides support to ministries of health. Publications include a situation analysis tool, which uses questions to establish the epidemiology of the population being served, and health system capacity (an approach that is similar to that described above for community assessment and asset mapping). They also publish templates and guides for planning and monitoring national strategies. Other WHO initiatives include a training manual for community health workers, suggested measures to reduce the risk of noise-induced hearing loss and a themed annual World Hearing Day; these initiatives are summarised in a recent article.Reference Chadha and Cieza56 The WHO offices can be contacted to obtain further support and advice.

For those who are delivering ear care on a regional or local level, it is nevertheless important to engage with national level strategies in ear and hearing care, either to encourage their development, or to see if it is possible to incorporate existing programmes into one's own work.

Development of newborn hearing screening in a region or country is contingent upon treatment availability, and has had variable success in low- to middle-income countries.Reference McPherson57, Reference Olusanya58 Automated testing of otoacoustic emissions or auditory brainstem responses has made screening easier, although low-cost community screening using a noise generator has also been described.Reference Ramesh, Jagdish, Nagapoorinima, Suman Rao, Ramakrishnan and Thomas59 Screening in the community is important to consider, particularly in regions with high rates of non-hospital births.Reference Kapil60

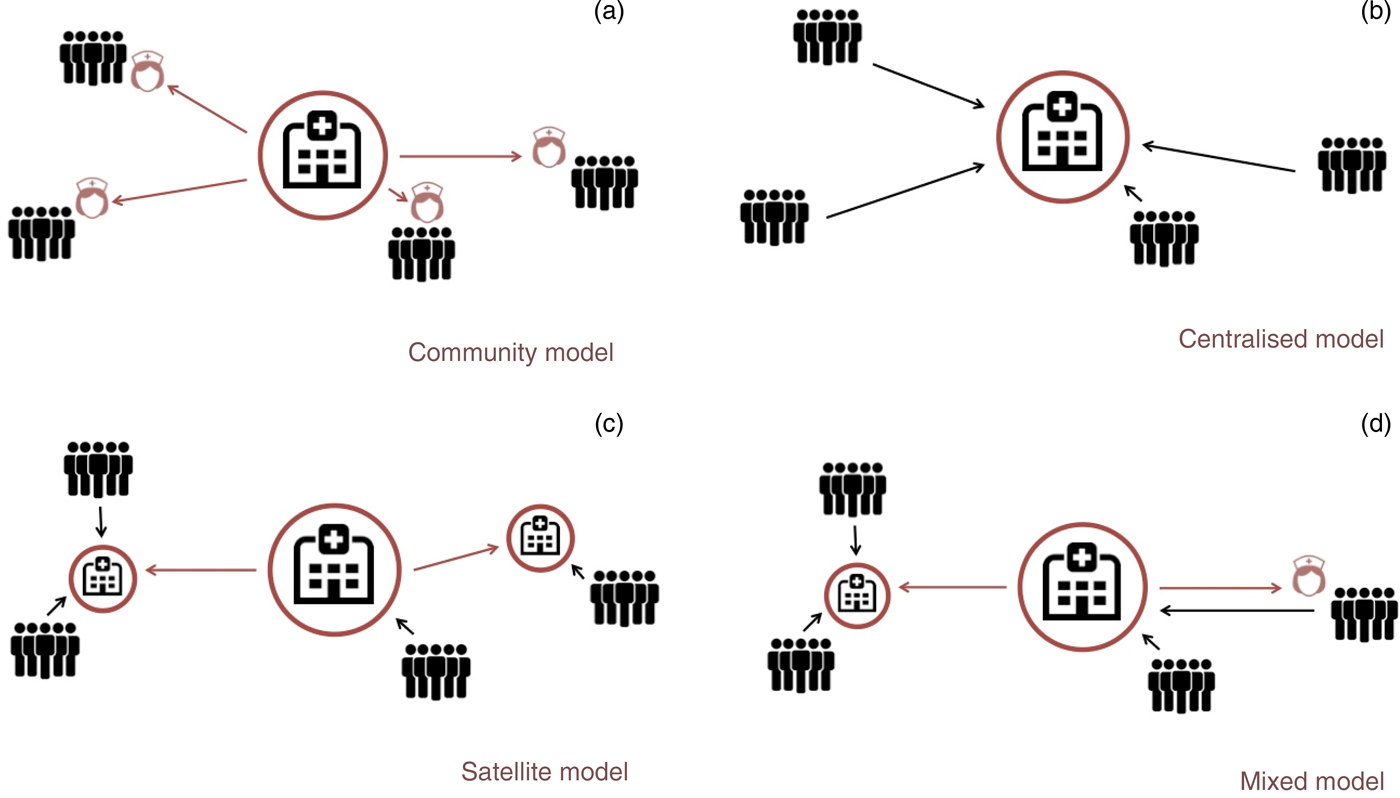

I will now discuss existing models for delivery of care, which I classify as the community model, the centralised model, the satellite model and the mixed model (Figure 2). I provide successful examples of each.

Fig. 2. Models for delivery of ear and hearing care: (a) community model, (b) central model, (c) satellite model and (d) mixed mode (see main text for details).

Community delivery of care model

The community model (Figure 2a) is one where ear care is delivered in the community. This may include general or targeted screening for ear disease (if estimated disease prevalence is high enough to make this worthwhile), and delivering medical treatment. Often this model is based upon using community or primary health workers, whether those trained just to deliver ear and hearing care, or by adding training in ear and hearing care to existing community or primary health workers.

Primary ear care delivered by nurses or healthcare workers has been described in several countries, including Australia, Nepal, Honduras and Ethiopia,Reference Shrestha, Baral and Weir61–Reference Eikelboom, Weber, Atlas, Dinh, Mbao and Gallop64 but almost all that has been published is descriptive, with little or no evaluation of the clinical effectiveness or logistical or financial viability of such programmes.Reference Whiteford, White and Stephenson65 There are, however, studies from NepalReference Youngs, Weir, Tharu, Bohara and Bahadur66 and AustraliaReference Peever and Ward67 showing that community health workers can develop good otoscopy skills. The WHO has produced a set of training manuals for primary ear and hearing care, although these are undergoing revision at the time of writing. A randomised trial of the education of mothers in ear care using the existing WHO Primary Ear and Hearing Care Training Resource: Basic Level 68 demonstrated no change in the incidence of CSOM in children after the educational intervention.Reference Clarke69 The WHO has also produced a guide to community-based ear and hearing rehabilitation.9

There is evidence from other studies that community health workers can improve health measures such as immunisation rates, breastfeeding rates and child morbidity.Reference Lewin, Munabi-Babigumira, Glenton, Daniels, Bosch-Capblanch and van Wyk70 What is also evident from previous research is that to be effective and motivated, and to increase staff retention, community health workers must be supported by sufficient, relevant and high-quality training. This is achieved by close collaboration, support and supervision from health professionals and the health system, and by good working conditions, including an appropriate workload.Reference Glenton, Colvin, Carlsen, Swartz, Lewin and Noyes71 Historically, many community health worker programmes failed because of inadequate training or support of workers on the job.

The community model has the potential to achieve good ‘buy in’ from patients. Research from other contexts shows that patients value community health workers as approachable, because often they share characteristics with them.Reference Glenton, Colvin, Carlsen, Swartz, Lewin and Noyes71 The disadvantages of this model are that it may prove expensive:Reference Vaughan, Kok, Witter and Dieleman72 there is a lot of training involved, and logistical costs. The model may not be cost-effective in areas with low disease prevalence. It is also difficult to deliver complex care in the community, because equipment such as endoscopes or microscopes will probably not be available. However, treatments such as ear washouts or audiological screening can be performed.

Community model example

In 2016, Dr Ian Traise, an Australian general practitioner, volunteered to provide primary ear care clinics in the Safe Haven Community Center in the slum area of Payatas in Manila, the Philippines. He observed a high prevalence of CSOM, and so subsequently trained one of the Filipino childcare workers (Figure 3) to perform otoscopy, video-otoscopy, tympanometry, and ear toilet with iodine. He also taught her how to diagnose ear disease, with digital image and case review performed by himself in Australia, to aid learning and clinical management.

Fig. 3. A childcare worker in the Philippines trained to diagnose and treat ear disease. Published with patient's permission.

At the time of writing, 60 children in the community centre are under review for CSOM, some of whom have been cured, but others have ongoing disease. This programme is now expanding to other local community centres.

Central delivery of care model

I use the central model (Figure 2b) to describe a single national or regional ear or hearing care centre to which patients must travel. The advantages are that it is easier in this model to provide a comprehensive range of specialist care, including surgery, as only one centre is used. This can also help to keep costs low, to provide continuity in trainingReference Waller, Larsen-Reindorf, Duah, Opoku-Buabeng, Edwards and Brown73 and to implement processes for continual improvement.

However, one thing to consider is access to care: if there is poor transport infrastructure in the region or country, or the costs of transport are prohibitive, some patients may not be able to access such a centre.

Central model example

The Children's Surgical Centre is a charity hospital in Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia. It provides treatment for disability to adults and children, including ear disease treatment. It is the only institution in the country regularly undertaking otological surgical procedures, through local surgeons (Figure 4) who were trained by surgeons from the UK (including the author of this article).

Fig. 4. Mastoidectomy performed by a local surgeon at the Children's Surgical Centre, Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

Cambodia is fairly compact, and there is public transport access to Phnom Penh throughout the country. Hence, a central model for service delivery seems appropriate, and data analysis shows that patients do indeed come from across Cambodia. Nevertheless, there are future plans to perform an outreach visit to the most remote and poor parts of Cambodia. Concerns exist that this population may still have financial and logistical barriers to access.

Satellite delivery of care model

The satellite model uses a ‘hub and spoke’ model (Figure 2c). The hub is the centre of expertise, but linked to other centres around the region or country. These other centres could be permanently staffed (for example, located in a health centre) or temporarily staffed by workers from the hub (for example, utilising local health centres or schools when needed, or even using makeshift facilities). Whichever model is chosen, some integration with local healthcare providers is always a good idea, as this helps provide continuity of care. If it is a visiting service, resident health workers can be invaluable in publicising and identifying potential patients.

The satellite model improves access for patients compared to the central model, and so should certainly be considered when transport infrastructure is poor. However, it obviously costs more to the provider than the central model, and introduces risks regarding the breakage of medical equipment if this has to be regularly transported. The satellite model usually uses road transport, but there is no reason to not consider other modes of transport: for example, ships have been used for delivering general surgical care (by the hospital ship charity Mercy Ships; www.mercyships.org).

When a satellite model uses a visiting service, there is also a risk of over-treatment. For example, if a patient with a chronically discharging ear is seen, it may be tempting to perform surgery in that same visit, but there is a possibility that medical therapy could lead to disease resolution.Reference Smith, Hatcher, Mackenzie, Thompson, Bal and Macharia74

Satellite model example

Ear Aid Nepal provides medical and surgical ear care to the population of Western Nepal. Care is delivered from a centralised hospital in the city of Pokhara, but access to hospitals can be difficult for many rural populations,Reference Paudel, Upadhyaya and Pahari75, Reference Yadav76 particularly because of the mountainous terrain.

Ear Aid Nepal has, over several years, organised over 30 ear camps in different villages across Nepal. Medical and surgical services are usually delivered from local hospitals or health centres at these villages, but occasionally from makeshift tents. All equipment has to be transported to these camps (Figure 5), including generators and buckets to transport water if needed. Thousands of rural Nepalese patients have been treated through these camps, including receiving medical and surgical treatment, and hearing aid fitting.

Fig. 5. Unloading equipment at an ear camp organised by Ear Aid Nepal.

Mixed delivery of care model

A mixed model combines community care with a satellite or central model (Figure 2d). It is in many ways a good solution where comprehensive care is desired but the target population is difficult to access. Disease can be identified and treated in the community, and the patient sent to a local centre for specialist or more complex intervention if needed. However, such a model is costly.

Mixed model example

Aboriginal communities in Australia have amongst the worst prevalence of CSOM in the world,Reference Coates, Morris, Leach and Couzos77 of up to 60 per cent.Reference Morris, Leach, Silberberg, Mellon, Wilson and Hamilton78 Within this group, rates are highest in the 21 per cent of the Aboriginal population that live in remote or very remote areas. This can make access to care difficult.

In the Pilbara and Kimberley regions of north-western Australia, a number of organisations work to deliver a package of care from the community through to the hospital. The Earbus Foundation of Western Australia, the Western Australia Country Health Service and the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Service will travel by car or private plane (Figure 6) to remote communities. Children in these areas are screened for ear disease, and treated if possible. Adults are seen upon request. The community team includes a healthcare worker, an ENT doctor and an audiologist. Patients who cannot be treated in the community because they are deemed to need surgical care are scheduled for elective surgery at a locoregional hospital, which acts as a satellite hospital for periodic visits from ENT surgeons from the state capital of Perth.

Fig. 6. The author (right), with a nurse and audiologist, preparing to fly to a remote Aboriginal community in the Kimberley region of north-western Australia.

Telehealth

Telehealth describes the delivery of healthcare at a distance, which has been incorporated into ear and hearing care in recent years. It can be cost-effectiveReference Nguyen, Smith, Armfield, Bensink and Scuffham79 and provide additional capacity to existing delivery of care models. As the availability of the internet continues to grow, and phone technology becomes more widely available (including in low- to middle-income countries), use of telehealth and mHealth (mobile health) seems likely to grow, notwithstanding potential difficulties in scaling such models.

Tele-otology is the capture of otoscopic images and patient data for remote assessment. It has been successfully used in NepalReference Mandavia, Lapa, Smith and Bhutta80 and South Africa,Reference Biagio, Swanepoel de, Laurent and Lundberg81 and remote regions of AustraliaReference Smith, Dowthwaite, Agnew and Wootton82, Reference Reeve, Thomas, Mossenson, Reeve and Davis83 and the USA.Reference Ciccia, Whitford, Krumm and McNeal84, Reference Kokesh, Ferguson and Patricoski85 However, images captured by a non-specialist can sometimes be suboptimal.Reference Biagio, Swanepoel de, Laurent and Lundberg81, Reference Lundberg, Westman, Hellstrom and Sandstrom86

Tele-audiometry has been utilised in a number of applications, including remote diagnostic audiometry,Reference Swanepoel de, Koekemoer and Clark87 otoacoustic emissions testing,Reference Krumm, Huffman, Dick and Klich88 auditory brainstem response testing,Reference Krumm, Huffman, Dick and Klich88, Reference Ramkumar, Hall, Nagarajan, Shankarnarayan and Kumaravelu89 hearing aid fittingReference Penteado, Ramos Sde, Battistella, Marone and Bento90 and cochlear implant programming.Reference Eikelboom, Jayakody, Swanepoel, Chang and Atlas91–Reference McElveen, Blackburn, Green, McLear, Thimsen and Wilson93

Conclusion

Delivery of ear and hearing services in remote or resource-constrained environments can be challenging. A systematic approach, with recognition of challenges and limitations, and an acknowledgement of previous successes and failures, can help to optimise the chance of success.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Mike Smith (Ear Aid Nepal), Ian Traise (Safe Haven Community Centre), Kelley Graydon (University of Melbourne), James O'Donovan (University of Oxford) and Shelly Chadha (WHO) for their input into this manuscript.

Competing interests

None declared