Introduction

‘ A just society can be judged by how it supports people who need care to live independent lives’ (Moullin, Reference Moullin2008, p. 4). Increasingly society can also be judged by how it supports those providing care at home. Parents are expected to care for their children, extending to all aspects of a child’s life and development (Roberts and Lawton, Reference Roberts and Lawton2001). However, parental roles usually change and diminish as children grow. Although political recognition now more closely aligns with scholarly recognition of the importance of public childcare for the economy and work-family reconciliation (Meyers and Gornick, Reference Meyers and Gornick2005; Crompton and Lyonette, Reference Crompton and Lyonette2006; Directive 2019/1158, 2019), less attention has been paid to the growing group of parents who raise and care for a disabled child, i.e., a child with additional or complex care needsFootnote 1 (referred to here as parent-carers).

Children with complex care needsFootnote 2 require prolonged care, therefore parent-carers need to develop medical, nursing, and other skills to support their children (Whiting, Reference Whiting2013). For parent-carers, providing care often goes beyond ‘typical’ or ‘ordinary’ parenting, and thus multiple sources of support, including special pedagogy, medical care, transportation, and emotional care are needed (e.g., Stiell et al., Reference Stiell, Shipton and Yeandle2006). Although the need for additional support and their life-long care commitment distinguishes parent-carers from other parents, data collection is unsystematic, and research remains fragmented. Thus, knowledge of parent-carers’ experiences is limited, including access to childcare support.

Childcare is a key instrument for combatting socio-economic inequities among children and parents (Pavolini and Van Lancker, Reference Pavolini and Van Lancker2018). For parents, public childcare can reduce family care to enable parents’ broader contributions to society (Javornik and Ingold, Reference Javornik and Ingold2015) and can also create opportunities for parents to enter or remain in the labour market (Meyers and Gornick, Reference Meyers and Gornick2005; Nieuwenhuis et al., Reference Nieuwenhuis, Need and van der Kolk2019). Additionally, many parent-carers may wish to prioritize caring for their children.Footnote 3 But to what extent is childcare an actual resource, and for whom? Here, we note a glaring omission. Most of the otherwise rich, comparative childcare literature, including the conceptualization and operationalization of comparative indicators (Yerkes et al., Reference Yerkes, Javornik and Kurowska2019; Dobrotić, Reference Dobrotić2022) focuses on parents but not parent-carers. Broadly, within disability studies, research often emphasizes the experiences of children with complex care needs, such as their exclusion in school settings (Dixon et al., Reference Dixon, Braye and Gibbons2021). Studies from parent-carers’ perspective in relation to childcare are nearly absent (see Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017, for an exception). The childcare needs of parent-carers are similarly absent from the comparative family policy literature. Lastly, there is no comparative database or set of indicators to facilitate cross-national childcare policy comparisons for children with complex needs.

A limited understanding of whether childcare for parent-carers is available, affordable, and accessible is problematic given the additional vulnerabilities parent-carers face, including higher economic burdens. Caring for a child with complex care needs affects family members’ quality of life, gender roles, financial resources, autonomy, employment, time use, health and stress levels, and demographic life events, such as divorce or the birth of another child (Giulio et al., Reference Giulio, Philipov and Jaschinski2014). These limited studies suggest childcare policy design (i.e., who policies are targeting, in what ways, and how childcare policies are constructed) is crucial for parent-carers’ opportunities, considering good quality, flexible services tailored to their needs, are in scarce supply (Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017). Against this background, this article contributes to current comparative childcare scholarship by expanding existing conceptualizations and operationalizations to consider childcare policy design from the perspective of parent-carers.

Our contribution is twofold. Conceptually, we critically discuss the applicability of current childcare policy indicators when applied to the complex care needs faced by parent-carers, integrating the capability approach and the social model of disability (Sen, Reference Sen1992; Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2004; Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019). Integrating these perspectives creates conceptual space to reconsider established policy indicators, considering the diverse and complex needs of this understudied group. Empirically, we explore the applicability of our conceptualization by comparing childcare policy designs in England and the Netherlands, thereby extending existing research on capabilities in work-family policy (Hobson, Reference Hobson and Hobson2014; Javornik and Kurowska, Reference Javornik and Kurowska2017; Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019; Zagel and Lohmann, Reference Zagel, Lohmann, Nieuwenhuis and Lancker2020). We selected two countries with a similar market mechanism of childcare provision (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan2012) to focus on nuanced differences in national policy designs. We note that childcare is a devolved matter in the United Kingdom, and in this study, we focused on England. By broadening extant childcare policy analysis to include the design of policies targeting children with complex care needs, this paper also contributes to the broader methodological discussion around comparability and commensurability of childcare policy indicators (e.g, Javornik, Reference Javornik2014; Sirén et al., Reference Sirén, Nieuwenhuis and Van Lancker2020).

Supporting parent-carers and evaluating childcare policy design

The challenges parent-carers face due to their child’s special development needs (Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017; Reisel et al., Reference Reisel, Nadim and Brekke2020) can have different consequences for parents. The complex care needs these parents face can result in positive parental experiences, such as being able to expand one’s community or becoming better connected as a family unit (Stainton and Besser, Reference Stainton and Besser1998). Positive effects notwithstanding, caring for children with complex care needs means parent-carers have a life-long care commitment to provide care beyond ‘ordinary’ parenting (Whiting, Reference Whiting2013). For some, such experience results in better connections as a family unit; for others, it leads to family dissolution (Wei and Yu, Reference Wei and Yu2012).

An absence of childcare can negatively impact parent-carers in multiple ways (Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017). First, it limits parent-carers’ ability to find employment that matches their qualifications, often in gendered ways, disproportionately affecting mothers who are more likely to resort to part-time work (Reisel et al., Reference Reisel, Nadim and Brekke2020) or leave paid employment (Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017). Second, parent-carers are often more reliant on informal childcare resources than other parents, such as care provided by relatives (Rosenzweig et al., Reference Rosenzweig2008), which may limit parent-carers’ capabilities to combine care with other activities outside the family. Third, children with complex care needs may require specialized medical care (Reisel et al., Reference Reisel, Nadim and Brekke2020). Childcare services where medical needs can be addressed may not always be available and parent-carers may experience long wait lists for specialized childcare settings. Limited availability of specialist childcare can similarly affect parent-carers’ capabilities to engage in activities beyond caregiving and work.

In short, the limited evidence suggests that while childcare is a key resource for parent-carers, in practice, parent-carers may face barriers that decrease its potential. By applying an integrated capability-social model of disability approach to evaluate childcare policy design, we can assess the availability, accessibility, and affordability of childcare services for parent-carers, and thus the extent to which these services may function as a resource to support combining caregiving with other valued activities.

The capability approach and the social model of disability

Originating from Sen (Reference Sen1992) and Nussbaum (Reference Nussbaum2011), the capability approach (CA) offers a critique of traditional welfare economics predominantly focused on income inequality or utility. Sen (Reference Sen1992) characterizes the capability approach as a versatile framework of thought, serving as a way of conceptualizing normative issues and evaluating individual well-being. The CA addresses human diversity by focusing on the wide range of functionings (what people achieve) and capabilities (real freedoms or opportunities) as the basis for evaluation (Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2005). People need varying types and amounts of resources to reach comparable levels of well-being, so equal distribution of goods does not lead to equal well-being. In addition, the CA underscores how individual and socio-environmental factors shape people’s ability to transform resources into actual functioning. At its core, the CA directs attention towards what individuals can achieve or become (Sen, Reference Sen, Nussbaum and Glover1995; Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2005), highlighting that people vary in their freedoms or capabilities to convert resources (such as income) into meaningful achievements (Sen, Reference Sen1999).

Within the comparative social policy literature, the CA is increasingly used to evaluate social policies (e.g., Yerkes et al., Reference Yerkes, Javornik and Kurowska2019), for example, to highlight the disparities in institutional policy design (e.g., availability and accessibility; see Javornik and Kurowska, Reference Javornik and Kurowska2017; Yerkes and Javornik, 2018). Equal access to resources, including social policies, does not guarantee equal capabilities to live valued lives. For example, a parent-carer of a child with autism might have access to the same subsidized daycare as other parents, but the facility may lack staff trained to address the child’s sensory or behavioural needs. Consequently, while the service is technically available, the parent-carer cannot use it effectively, highlighting a gap in capabilities.

A capability approach to childcare services would emphasize ensuring that all families, regardless of their circumstances, have real opportunities to access affordable and accessible childcare. This involves not only offering these services but also addressing the various individual, social, and environmental barriers that may prevent parent-carers from fully utilizing these services. By applying the CA, the focus shifts from measuring outcomes (such as whether parent-carers utilize childcare or not) to evaluating how childcare policy design impacts parent-carers’ real freedoms to access and benefit from these services, given their diverse needs and circumstances. Fundamentally, the CA stresses the importance of personal abilities, resources, and supportive external circumstances in enabling individuals to live valued lives (Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2004), offering a broader perspective on inequality and ensuring a context-sensitive assessment (Sen, Reference Sen1999).

Two prominent models in the disability literature are the social model and the medical model. The former distinguishes between impairment (i.e., physical or mental conditions) and disability, signifying limitations in community participation due to societal, economic, and environmental factors (Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2004). Hence, disablement is seen to arise from the social barriers encountered by individuals with impairments. In contrast, the medical model views disability as a “deficit from the norm, a malady to be fixed through physical therapy, technological devices, and personal willpower” (Manago et al., Reference Manago, Davis and Goar2017, p. 170), a perspective explicitly rejected by the social model of disability.

A key distinction between the social model of disability and the CA is that the social model focuses on eliminating societal barriers creating impairments, whereas the CA incorporates personal agency and the interaction between individual impairments and social-environmental factors (Trani et al., Reference Trani, Bakhshi, Bellanca, Biggeri and Marchetta2011). In line with Burchardt (Reference Burchardt2004) and Baylies (Reference Baylies2002), we integrate the CA and the social model of disability, taking a policy evaluative perspective (see, e.g., Yerkes et al., Reference Yerkes, Javornik and Kurowska2019). In doing so, we attempt to account for disparities arising from social factors, as they play a critical role in shaping parent-carers’ capabilities and individual well-being. Both frameworks prioritize the elimination of societal barriers to effectuate transformative change, emphasizing the pivotal role of social policy in facilitating comprehensive societal participation (Burchardt, Reference Burchardt2004). As such, the integration of these frameworks is particularly apt for our conceptualization and operationalization of childcare availability, accessibility, and affordability for children with complex care needs, an undertaking not currently possible with other comparative frameworks.

Neither the CA nor the social model of disability are universally embraced by scholars. The CA has been criticized for prioritizing individual freedom over social solidarity, thereby placing greater emphasis on personal liberty rather than collective cohesion (Dean, Reference Dean2009). Yet while the CA maintains ethical individualism, it is inherently relational (Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2005) and is distinct from other analytical frameworks in its recognition that people value a myriad of activities in life. As such, it allows for the recognition of the valued beings and doings of parent-carers in relation to their childcare needs. The social model has been criticized for focusing unilaterally on social factors, such as discrimination (e.g., Terzi, Reference Terzi2005). Some scholars advocate using the capability approach to rethink the concepts of impairment and disability (Terzi, Reference Terzi2005), whereas others suggest integration of the CA requires attention to not just social aspects of disability but also social–relational conditions (Reindal, Reference Reindal2009).

These debates notwithstanding, an integrated capability-social model approach allows us to open up the theoretical space to conceptualize the real opportunities of parent-carers from a childcare policy design perspective. This conceptualization and operationalization extends previous capability-based evaluations of childcare policy design (Yerkes et al., Reference Yerkes, Javornik and Kurowska2019), evaluating the extent to which it potentially enhances or hinders capabilities (i.e., what parent-carers can effectively do and be) (Kurowska, Reference Kurowska2018; Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019). Taking a CA evaluative perspective shifts away from the assumption that individuals are equally capable of accessing resources to live valued lives (Sen, Reference Sen1992). Childcare services not designed to accommodate the needs of parent-carers can limit parent-carers’ capabilities. Integrating the CA with the social model of disability allows for critical reflection on existing comparative indicators and an expansion aimed at accounting for the policy contexts in which parent-carers are embedded (e.g., Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2005).

Parent-carer capabilities in England and the Netherlands

The work-family policy context shapes the ways in which individuals are supported or constrained in translating policy resources into childcare capabilities (i.e., parent-carers’ real freedoms to arrange childcare in a way that allows them to lead valued lives). Historically, England has considered care a private family matter (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan2012) resulting in a delayed development of work-family policies, including childcare (Daly, Reference Daly2010). Despite improvements in recent decades, women continue to spend more time taking care of the home and children (Chung et al., Reference Chung2021). Moreover, England struggles with nursery provision (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2017) and costly formal childcare, making its availability highly dependent on families’ financial resources (Lloyd, Reference Lloyd2019). Consequently, parent-carers with lower earning capacity often turn to informal care provisions (Simon et al., Reference Simon2022). In the Netherlands, work-family policies developed relatively late from the 1990s onwards (Yerkes and den Dulk, Reference Yerkes and den Dulk2015). Similar to England, cultural care norms continue to be gendered, emphasizing mothers as caregivers, which influences policies and behaviours. Comparatively, the Netherlands has the largest proportion of women working part-time (Eurostat, 2020), with relatively high rates of formal childcare services used for three days or less and an ongoing preference for informal care alternatives (Yerkes and den Dulk, Reference Yerkes and den Dulk2015; Eurostat, 2021).

Within the childcare literature, the UK and the Netherlands are often grouped together (Moss, Reference Moss2008; Lloyd and Penn, Reference Lloyd and Penn2010; Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019) due to their similar market-based approach to childcare and the nature of devolved powers in the UK setting. England and the Netherlands, our focus here, share similar decentralization characteristics, whereby childcare policy responsibilities are spread across national and local governments. These similarities provide a foundation for our comparative analysis, while our conceptualization and analysis allows us to highlight crucial differences affecting parent-carers’ real opportunities, adding nuance to this existing grouping in the comparative literature.

A capability-social model of disability approach: conceptualizing childcare indicators for children with complex care needs

Childcare availability, accessibility, and affordability vary widely in their conceptualization within the childcare literature (Plantenga and Remery, Reference Plantenga and Remery2009), as well as childcare quality and flexibility (see Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019). Definitions often differ depending on whether childcare is viewed as a resource for parents or children’s rights (Van Lancker and Ghysels, Reference Van Lancker and Ghysels2016; Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019). We focus here on childcare as a potential resource for parent-carers, while recognizing the need for indicators that incorporate children’s needs, and acknowledge there may be a misalignment between the caring support preferences of parent-carers and their children, which is beyond the scope of this paper. Additionally, given the complexity of this analysis, we focus our conceptualization on availability, accessibility, and affordability. As other aspects of childcare policy are less relevant without accessible care (Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019), we prioritize these aspects of policy design. Future research conceptualizing childcare quality and flexibility from a parent-carer perspective is needed, (Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017). We return to this point in the Discussion. Lastly, we conceptualize and operationalize each aspect of childcare policy design separately, while recognizing that, in practice, they interact in multiple, meaningful ways (for more details on this see Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019).

Availability

Childcare availability is generally studied as a means of improving mother’s labour market participation (Nieuwenhuis et al., Reference Nieuwenhuis, Need and van der Kolk2019) or to reduce gender inequality in the domestic sphere (Bianchi and Milkie, Reference Bianchi and Milkie2010). For parent-carers in particular, childcare availability is highly salient: when supply is low, they report poorer health (Rosenzweig et al., Reference Rosenzweig2008).

With this in mind, we propose a three-fold measure of availability: the dominant mechanism of childcare provision (state, market, or non-profit provision (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan2012)); the approach to disability (social or medical); and whether childcare is provided as a right to children with complex care needs. Many extant studies define availability as the provision of formal policies and services by public institutions, the private market, or not-for-profit organizations. These studies often subsequently operationalize availability as equivalent to enrolment rates (Sirén et al., Reference Sirén, Nieuwenhuis and Van Lancker2020). Yet scholars increasingly recognize that enrolment rates are ill-suited as an indicator of childcare availability because they reflect the outcome of childcare rather than availability itself (Javornik, Reference Javornik2014). Alternatively, scholars suggest focusing on the prevailing mechanism of provision (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan2012). Focusing on the mechanism through which care is provided (public, private, not-for-profit, or mixed) is an improvement but insufficient for fully capturing service availability for children with complex care needs.

Additionally, from a capability–disability perspective, conceptualizing childcare availability for children with complex care needs requires understanding the dominant model of provision for childcare services as well. Countries differ in their approach to disability (i.e., whether they focus on a predominantly social or medical approach). Meaning, is childcare for children with complex care needs medicalizing, or are barriers to accessing childcare services reduced?

Some childcare scholars have also conceptualized availability in relation to children’s right to childcare (Javornik, Reference Javornik2014; Yerkes and Javornik, 2018), ensuring the availability of childcare is less affected by variations in childcare supply (Javornik, Reference Javornik2014). Similarly, for parent-carers, a guaranteed right to care is salient, particularly in countries relying on market or mixed-market care where service providers set eligibility rules, significantly affecting availability between groups. In combination with the dominant mechanism of provision and the reliance on a social or medical model, the guaranteed right to childcare is therefore of crucial importance for parent-carers’ capabilities.

Accessibility

Childcare availability and accessibility are often conflated, with studies operationalizing accessibility based on the number of childcare places available. Important conceptual distinctions exist, however, between availability and accessibility (European Commission and Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers, 2022). Whereas availability refers to the formal provision of childcare, accessibility refers to the conditions needed to use childcare in practice (i.e., eligibility conditions) (Javornik, Reference Javornik2014; Yerkes and Javornik, 2018). Eligibility conditions generally refer to admission criteria (e.g., the age of the child). In publicly subsidized, market-based systems, eligibility conditions can also include parental-related eligibility aspects to access childcare subsidies, such as employment requirements. This conceptualization, while useful, needs to be broadened to address accessibility issues for parent-carers. They run the risk of being denied access to formal care settings due to the special needs of their child, impacting their childcare capabilities.

Our broadened conceptualization highlights five potential barriers to accessibility for parent-carers (Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017). A key first issue relates to physical access to childcare facilities for children with complex care needs, including whether a ramp and/or elevators, sound-proof and/or light-effect free rooms, and calm-down rooms are available (e.g., for children with behavioural disabilities). In the absence of these physical necessities, childcare services are inaccessible for children with complex care needs and their parent-carers. Second, admission criteria can differ for children with complex care needs (e.g., providers may not admit children with complex care needs). This barrier can be removed using national-level, anti-discrimination legislation. Without a legal requirement, childcare settings can refuse a child with complex care needs, consequently hindering the childcare capabilities of parent-carers. Third, transportation to and from childcare services can affect accessibility, particularly for children who require specialized transport. For example, children may require a wheelchair or may use medical equipment (e.g., oxygen or feeding tubes), which makes regular modes of (public) transportation less useful.

These aspects of accessibility relate to children’s care needs; two further aspects of accessibility relate to parent-carers’ situations. Governments may provide supplemental benefits for care services targeted at children with complex care needs and/or benefits specifically targeting people (including children) with complex care needs. Whether such benefits are provided has important implications for affordability, which we discuss below. However, accessing these benefits may first require parent-carers to meet eligibility criteria, such as being employed. Second, eligibility criteria might include a needs assessment, which conceptually can also be considered an issue of access. Namely, needs assessments can act as a potential barrier to parent-carers’ capabilities (e.g., when they are unable to claim these benefits and services) as well as a potential enabler of parent-carers’ capabilities (e.g., if the child is eligible for specialized (child)care benefits and services such as personal care budgets to purchase home care).

Affordability

Given the extra expenses involved in caring for their child (Vinck, Reference Vinck2019), including medical expenses and necessary care-related goods and services that erode household income (John et al., Reference John, Thomas and Touchet2019), childcare affordability significantly affects parent-carers’ childcare capabilities. In England, a study found that one-third of families with children with complex care needs had to reduce spending on essentials like food or heating (Contact A Family, 2012), leading to subsequent health issues for parents. Moreover, low-earning parent-carers are likely to face even greater challenges due to high childcare costs, which have been prohibitive for low-income families (Gornick and Meyers, Reference Gornick and Meyers2003; Pavolini and Van Lancker, Reference Pavolini and Van Lancker2018).

Extant childcare literature regularly conceptualizes affordability as the percentage of net household income spent on childcare (OECD, 2022) and funding rules (Yerkes and Javornik, 2018).Footnote 4 For families with typically developing children, this conceptualization is useful. However, it is insufficient for addressing affordability for parent-carers given the additional costs outlined above (e.g., Vinck et al., Reference Vinck, Lebeer and Van Lancker2019). Conceptualizing and operationalizing these additional costs is challenging because they are only measurable to a certain extent, with various ways of measuring the direct costs (e.g., health care services, personal care, assistive devices) of childhood disability (World Health Organization, 2011; Stabile and Allin, Reference Stabile and Allin2012). Direct economic costs of disability (i.e., the additional costs families sustain because of children’s complex care needs) depend on national and local contexts (e.g., the availability of social and health care benefits). Indirect economic costs are also evident, for example, the loss of parental (maternal) employment. Mothers of disabled children are less likely to work than mothers of typically developing children, often because of having to manage multiple, unpredictable, and life-long care responsibilities (Pavalko, Reference Pavalko, Settersten and Angel2011). Estimating indirect costs such as these is complex and requires data that are generally unavailable.

As additional direct and indirect economic costs of childhood disability can significantly hinder parent-carers’ childcare capabilities, the availability of disability benefits or other forms of supplemental benefits are crucial to ensuring affordable childcare. Affordability is therefore linked to accessibility because parent-carers need to meet eligibility criteria to qualify for such benefits, highlighting the difficulty of analytically and empirically separating intertwined policy design aspects (Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019).

Data and methodology

Capability-based evaluation of policy design

We applied our conceptualization in a comparative analysis of childcare policy design (see Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019). Similar capability-based evaluations of policy designs have been conducted on parental leave (Kurowska and Javornik, Reference Kurowska and Javornik2019). As an evaluative approach, it relies on operationalizing indicators built from a conceptualization grounded in an integrated capability-social model of disability approach and using policy and legislative documents alongside available secondary data to comparatively assess policy designs.

Data

To the best of our knowledge, data on childcare for children with complex needs are neither systematically collected nor available within comparative datasets. We thus relied on document analysis and extant childcare literature for our analysis. Documents were gathered between 2021–2022 and included national legislation texts, ‘grey literature’ (i.e., policy documents), government websites, and the website of the Centrum Indicatiestelling Zorg (CIZ) for the Netherlands (for a full list of data sources, see Supplementary Materials). For ease of comparison with extant childcare policy indicators, our analysis concentrated on childcare for children with complex care needs through the age of five. While we included services available to parent-carers, such as personal budgets, additional benefits, and transportation services, our analysis focused solely on mainstream childcare settings, excluding the availability, accessibility, or affordability of specialist settings. Our analysis encompasses day care centres, preschools, nursery schools, playgroups, Sure Start Children’s centres, after school care, and childminders. We acknowledge the needs of parent-carers extend beyond the pre-school stage, while our focus remains on this stage of childcare services.

Operationalization

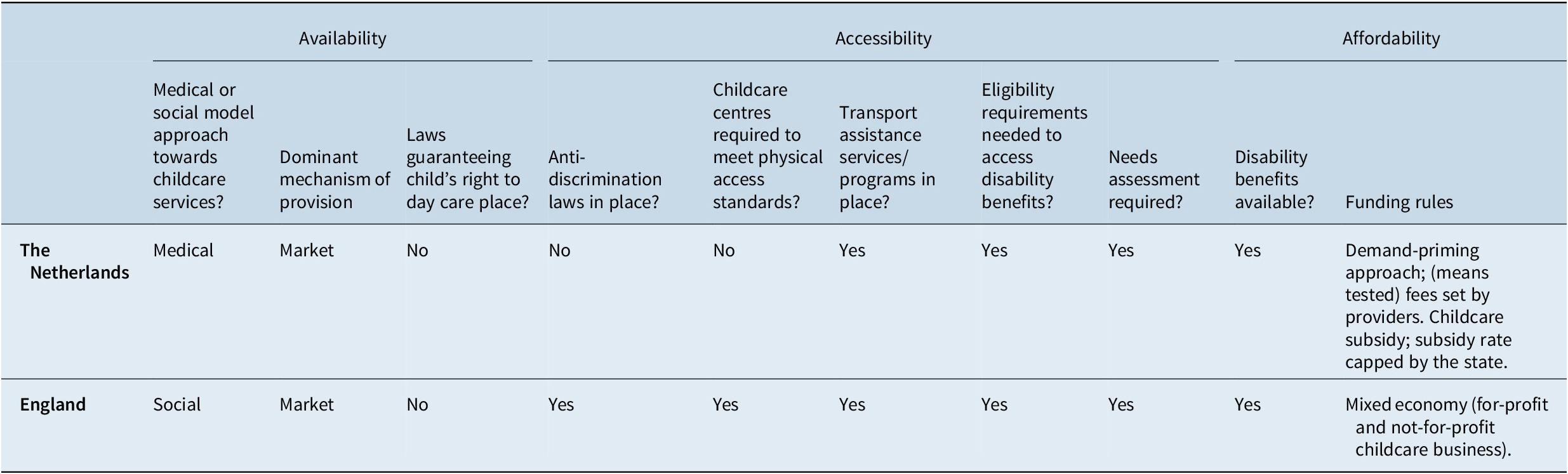

To assess availability using our conceptualization, we examined: (1) whether a country promotes a medical or social approach to disability; (2) the prevailing mechanism of childcare provision; and (3) the existence of laws guaranteeing a child’s right to a day-care place. The first indicator was categorized as the social model when government policy included a requirement to include children with complex care needs in standard care settings. A country was assessed as having a medical approach to disability in the absence of any mainstreaming policy objectives. Our second indicator, already used in earlier comparative childcare policy analysis, was assessed using existing literature (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan2012) as well as national and local government documents. Our third indicator, whether children with complex care needs have a right to childcare, was assessed as whether government documents on childcare or disability services explicitly stated that children with complex care needs were guaranteed access to a childcare place (yes or no).

Our conceptualization of accessibility was measured using a five-pronged operationalization broadening existing eligibility-based indicators to assess whether: 1) childcare services are required to meet physical access standards; 2) anti-discrimination legislation covering children with complex care needs exists; 3) special transportation services are available; 4) parent-carers need to meet eligibility requirements to access either supplemental or disability benefits; and 5) a needs assessment is required. As comparative data allowing for a detailed assessment of these indicators is currently largely unavailable, we relied on parsimonious indicators measuring yes or no for all five accessibility indicators.

Affordability was measured by examining whether: 1) disability or other additional benefits are available to parent-carers to cover the additional costs associated with childcare for children with complex care needs (yes/no); and 2) funding rules in the country. For the latter, we followed previous conceptualizations (e.g., Javornik, Reference Javornik2014; Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019), assessing whether funding is provided through direct funding streams to childcare providers, uses means-testing (i.e., placing a ceiling on parental fees), is based on a sliding-fee scale, or relies on a so-called demand-priming approach, whereby parents directly receive funding (i.e., via government subsidies). In the latter, childcare providers can choose to maximize profitability, leading to higher childcare costs, thereby decreasing parent-carers’ capabilities.

Although it was possible to distinguish a range of children’s disabilities as outlined in the 1998 UN Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities (e.g., physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments, or chronic illness), in practice, operationalizing such detailed indicators remains impeded by the dynamic and continuously changing care needs of children with disabilities throughout their lives and a lack of suitable data (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, Spencer and Read2010). Hence, we did not distinguish between the types of disabilities in our analysis, an issue we return to in the Discussion.

Results

Availability

Childcare availability for children with complex care needs is comparatively better in England, which incorporates aspects of the social model of disability, than in the Netherlands, which relies on the medical model (see Table 1). Although counterintuitive as the UK is known for promoting market-based childcare, England can be categorized as social because mainstreaming policy objectives are implemented in a manner aligning with a social model of disability. This approach is reflected in childcare legislation ( Childcare Act 2006; Childcare Act 2016 ), with general acknowledgement of the special needs of children with complex care needs. The Childcare Act 2016 changed the existing 2006 act significantly (e.g., local authorities being required to secure free childcare for qualifying children). Moreover, for children with complex care needs, childcare providers in England must adhere to the Equality Act ( Equality Act 2010 ), prohibiting discrimination against disabled children and mandating ‘reasonable adjustments’, such as needing extra equipment. However, childcare providers are allowed to charge for extra costs incurred, supporting the combination of market mechanisms alongside aspects of the social model. Compared to the Dutch medical model, the mainstreaming of services evident in England potentially enhances parent-carers’ capabilities, by increasing availability. Additionally, children with complex care needs became a national priority for the British government in 2008, through the Aiming High for Disabled Children programme (HM Treasury and Department of Education and Skills, 2007).

Table 1. Childcare indicators

Sources: OECD 2022, national legislation, policy documents, and governmental websites.

In contrast, childcare for children with complex care needs is medicalized in the Netherlands. Childcare policy for typically developing children is covered in the Childcare Act 2005 (Wet Kinderopvang), which makes no mention of children with complex care needs. Rather, they fall under four separate pieces of national legislation: the Youth Act 2015 (Jeugdwet, article 1.1), which is intended to provide support, help and care for young people under the age of eighteen (and their parent-carers) who have special and/or extra needs; the Health Care Act 2006 (Zorgverzekeringswet (ZVW)); the Act on Long-term Care 2015 (Wet Langdurige Zorg (WLZ)); and the Social Support Act 2015 (Wet Maatschappelijke Ondersteuning, (WMO)). The latter is meant to assist parents who need extra (medical) care or support for their child’s special needs. These separate pieces of legislation create a fragmented approach to care services for people with disabilities, particularly for children with complex care needs and their parent-carers. Moreover, most of it falls under the auspices of health care policy, with some addition of social services, creating a heavy reliance on a medical model. This medical approach to disability affects parent-carers’ capabilities, leading them to seek out specialized childcare services.

The second indicator of availability, the dominant mechanism of childcare service provision, is market-based in both countries. Market mechanisms diminish the capabilities of parent-carers, particularly in low-income families, given higher childcare costs (Yerkes & Javornik, 2018). Alongside affordability issues, market-based childcare in both countries is increasingly dependent on local authorities, following the significant decentralization of social services responsibilities from national to local levels (Martinelli et al., Reference Martinelli, Anttonen and Mätzke2017). Local authorities play a more pronounced role in childcare services in England, with the legal duty to provide parent-carers information and advice on local childcare service provision and attempting to secure sufficient childcare services for parents. This is known as the ‘Local Offer’ (Department of Education, 2018). This situation contrasts with the Netherlands, where despite having extensive responsibility for social care and social services, local authorities generally rely on providing parent-carers informational support (e.g., providing relevant information on day care and support options on their website). Additionally, most Dutch municipalities appoint a team whom parents can contact for questions about available services and their child’s special and/or medical needs. The decentralization in both countries and significant reliance on the local level can limit parent-carers’ capabilities, particularly across different geographical settings given the variation in the support provided by local authorities (e.g., Martinelli et al., Reference Martinelli, Anttonen and Mätzke2017).

The final indicator of availability, a child’s right to childcare, is not present in either England or the Netherlands for children with complex care needs; this can limit parent-carers’ capabilities, particularly those from disadvantaged groups such as low-income parent-carers and parent-carers from single households (Yerkes and Javornik, 2018).

Accessibility

Alongside explicit and more subtle differences between England and the Netherlands in childcare availability for children with complex care needs, we also see key differences in accessibility, with England providing childcare services more accessible to parent-carers. The first relates to the implementation or absence of anti-discrimination laws. In the Netherlands, no laws prohibit the discrimination of children with complex care needs in formal care settings. In England, in contrast, anti-discrimination legislation prohibits discrimination against children with complex care needs since 1995. The Equality Act (EqA) replaced the 1995 Disability Discrimination Act in 2010. It prohibits direct discrimination, indirect discrimination, harassment, and victimization (Stobbs, Reference Stobbs2015). For example, childcare providers are prohibited from denying services or providing a lower standard of service to a child with complex care needs. Additionally, childcare providers have a duty to make reasonable adjustments so that childcare settings are accessible to children (e.g., ensuring a child with autism has a safe place when they get too anxious or allowing a child with diabetes to have different meals). The advanced anti-discrimination legislation in England, including the reasonable adjustment duty, means parent-carers in England are less at risk of being denied access to childcare services, whereas parent-carers in the Netherlands cannot have the same expectations as childcare providers do not legally have to make reasonable adjustments based on a child’s care needs.

For the second indicator, childcare settings in the Netherlands are not obliged to meet physical access standards for children with complex care needs. In England, childcare settings must be psychically suitable for children with complex care needs, following the legal responsibilities of the EqA (2010). As a result, the childcare capabilities of parent-carers are enhanced given that they are at less risk of their child not being able to physically access a childcare setting. In terms of accessible transportation services, both countries provide some type of transport programmes for children with complex care needs to improve childcare accessibility, contingent on needs assessment. In the Netherlands, a parent’s health insurance company can (partially) cover these costs or parents can apply for transport services provided through the city council (as part of the Youth Act, 2015). In England, parent-carers can access transportation services for their child upon request, after a needs assessment from local authorities.

Our fourth and fifth indicators of accessibility show that eligibility requirements are needed to access disability benefits and needs assessments are required in both countries. This can create inequalities in parent-carers’ capabilities as local authorities may differ in their assessment of the same needs, once again introducing potential geographical inequalities (Martinelli et al., Reference Martinelli, Anttonen and Mätzke2017). Responsibility for needs assessments in England resides with local social services departments. In the Netherlands, dependent on the type of care parents need, needs assessments are carried out by local authorities and/or the Care Assessment Centre (Centrum Indicatiestelling Zorg (CIZ)). The latter becomes involved when parents require care that falls under the Long-term Care Act, once again underscoring the fragmented medicalization of (child)care for children with complex care needs in the Netherlands.

Affordability

Childcare costs are high in both countries compared to other European countries less reliant on market provision. In our analysis, despite England providing more financial support than the Netherlands, childcare in the Netherlands is slightly more affordable for parent-carers due to the high childcare costs in England (OECD, 2022). More data are needed, though, to accurately compare the costs incurred by parent-carers.

Supplemental benefits, such as a Disability Living Allowance (DLA; offered in England) or additional child benefits are offered to parent-carers in both countries. Although a needs assessment is required in both countries, only parent-carers in England can claim these benefits without further eligibility requirements such as employment. In England, once a local needs assessment has been conducted, parent-carers can apply for direct payments to buy childcare services or an education, health, and care (EHC) plan in addition to the regular childcare subsidies available to all parents (GOV.UK, n.d.-a). Additionally, they may be eligible for the Child Tax Credit (GOV.UK, n.d.-b) or the DLA (GOV.UK, n.d.-c) if their child has complex care needs. In contrast to other benefits, the DLA is not means-tested, individual savings are not considered, and both employed and unemployed parents are eligible. In addition, all eligible parents (i.e., employed parents) can apply for the Universal Credit to assist with childcare costs.

In the Netherlands, parent-carers are not eligible for extra funding under the current childcare legislation. If supplemental care is needed at a mainstream day care centre (e.g., a child needs a wheelchair), parents can request financial support from the local authority to cover these costs. Some costs may also be covered by a parent-carer’s health insurance. In addition, all parents in the Netherlands receive quarterly child benefit payments (independent of childcare benefits) to assist with the costs of childrearing. Parent-carers may qualify for additional child benefits once their child turns three until the age of 18, following a needs assessment from the Care Assessment Centre (CIZ). In contrast to England, parent-carers in the Netherlands are only eligible for such benefits if their child requires ‘intensive’ care and they are judged to have insufficient income and/or savings (CIZ, 2022). Such eligibility requirements to access supplemental benefits limit parent-carers’ capabilities, creating additional barriers to obtaining affordable childcare.

Childcare affordability can be further diminished by funding rules. Both countries follow a demand-priming approach (Immervoll and Barber, Reference Immervoll and Barber2006) whereby parents receive direct financial help for the childcare services they purchase on the market. This approach may hinder parents’ capabilities due to complexities in accessing entitlements. Navigating childcare and supplemental benefits across multiple authorities can be challenging for parent-carers, affecting their ability to access support. Additionally, the demand-priming approach disproportionately affects low-income families of parent-carers (OECD, 2022), with high childcare costs acting as a barrier to childcare enrolment.

Discussion and conclusion

Childcare policy is viewed as a crucial instrument in combatting social inequalities for both children and parents (Pavolini and Van Lancker, Reference Pavolini and Van Lancker2018; Nieuwenhuis et al., Reference Nieuwenhuis, Need and van der Kolk2019). However, the rich comparative childcare literature often overlooks the experiences and realities of parent-carers (i.e., parents of children with complex care needs) (Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017). Consequently, our understanding of childcare inequalities is incomplete. From a capability perspective, social policy design should consider that people require different types and amounts of service and benefits to achieve comparable levels of well-being (Robeyns, Reference Robeyns2005). Hence, childcare policy should consider the varying needs of families, more specifically those of parent-carers. Our study shows why the childcare capabilities of parent-carers differ from the capabilities of parents of typically developing children, underscoring the need for new comparative childcare policy indicators. Our ensuing conceptualization and operationalization, grounded in the integration of the CA and social model of disability, extend existing comparative childcare policy indicators, offering an innovative analytical lens to evaluate the potential of childcare to be an actual resource for parent-carers to combine care with other valued activities. This integrated approach reveals the profound effects of childcare policy design on parent-carers’ capabilities, simultaneously demonstrating that extant indicators cannot account for national-level differences in the approach to care for children with complex care needs.

Our analysis demonstrates that England combines a market-based approach to childcare with aspects of the social model of disability, whereas the Netherlands combines market-based provision with a medical approach. Consequently, parent-carers’ capabilities are generally higher in England than in the Netherlands given greater availability and accessibility. In England, the combination of national legislation emphasizing mainstreamed childcare services for children with complex care needs and the presence of anti-discrimination law increases parent-carers’ capability to choose childcare that best suits their needs and preferences (e.g., a daycare that is nearby their house). Consequently, accessible and available childcare increases parent-carers’ freedoms to allocate time to engage in activities they value alongside caregiving, including leisure pursuits, volunteering commitments, or pursuing further education opportunities. Conversely, parent-carers in the Netherlands face significant structural barriers, such as the risk of being denied service, due to the absence of protective institutional measures. This lack of safeguards can impact their caregiving decisions, leading to challenges such as limited childcare options, increased financial strain from seeking alternative solutions, and heightened stress from navigating an uncertain childcare landscape. These structural barriers significantly limit the capabilities of parent-carers in the Netherlands. We note, however, that parent-carers in England, despite having greater access to childcare subsidies and programs than parent-carers in the Netherlands, face greater barriers to affordability given the exceedingly high costs of childcare. Together, this analysis challenges conventional childcare policy comparisons grouping England and the Netherlands together (Moss, Reference Moss2008; Lloyd and Penn, Reference Lloyd and Penn2010), highlighting nuanced differences in their marketized childcare regimes once parent-carers’ capabilities are accounted for. Although the classification of the Netherlands and England as similar remains pertinent (i.e., parent-carers are governed by similar policies, including high childcare expenses), our analysis underscores the importance of examining the capabilities of distinct groups of parents within these traditional comparative approaches.

Moving forward, a nuanced intersectional integration of capabilities (Beuret et al., Reference Beuret, Bonvin and Dahmen2013) and the social model of disability would be useful to reveal how parent-carers’ capabilities are gendered, classed, and racialized. For instance, studies suggest gender inequalities exist, with mothers of children with complex care needs being more likely to have their labour earnings and hours affected (Brekke and Nadim, Reference Brekke and Nadim2017) and reporting poorer health (Masefield et al., Reference Masefield2020). Our study offers a foundation for continued research efforts, aiming to improve comparative childcare policy analysis by capturing how policy design shapes the capabilities of a broader group of parents (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan2012; Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019). Lastly, our analysis highlights the added difficulties parent-carers can face given geographical variation. The implementation of childcare policies at local levels in many countries can create additional barriers to parent-carers’ capabilities. Future research into the ways in which local childcare policy implementation helps or hinders parents, and in particular parent-carers’ capabilities, would be a welcome addition in this regard.

That notwithstanding, some challenges remain. First, our study focuses on the childcare capabilities of parent-carers without making a distinction between types of disability or care needs of children. We acknowledge that care needs range in complexity from mild to severe (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, Spencer and Read2010), impacting the needs and lived experiences of parent-carers in different ways. Due to the scope of our study and the absence of comparative data, we were unable to account for this diversity. Additionally, future research should consider linking mainstream childcare settings to specialist childcare services to better address the diverse needs of parent-carers and children with complex care needs. Theoretically, we argue for the integration of the capability approach and social model of disability (cf., Burchardt (Reference Burchardt2004) and Baylies (Reference Baylies2002)) for the purposes of evaluating childcare policy design. However, the usefulness and limitations of this integration remains a point of debate (see, e.g., Terzi, Reference Terzi2005; Reindal, Reference Reindal2009). Space limitations prevent us from considering these debates with more depth. Empirically, expanding our analysis to include cross-national comparisons with more countries is essential for a comprehensive understanding of parent-carers’ childcare capabilities. Such an expansion would allow for an exploration of how differing childcare systems (e.g., public, mixed models) influence the childcare capabilities of parent-carers, contributing to a more nuanced perspective on the intersection of childcare policy design and social inequalities. Finally, our study provides an initial exploration of three aspects of childcare policy design. Previous studies additionally illustrate the importance of service quality and flexibility for parent-carers (Brown and Clark, Reference Brown and Clark2017). Deeper and greater discussion is needed on the relationship between our three indicators (availability, accessibility, and affordability) and also other criteria, such as quality and flexibility, with the latter being least understood in the literature and very likely crucial to parents-carers’ capabilities. Such research is also needed to comprehensively develop high-quality comparative indicators that consider the specific needs of parent-carers. Our findings also suggest avenues for further research to truly understand parent-carers’ capabilities in reality, given we evaluate the design of policy rather than its implementation and lived experience. Despite these limitations, the conceptualization, operationalization, and application provided here offer an important next step in developing commensurable comparative childcare policy indicators to capture the capabilities of a broader group of parents, acknowledging the complexity of parent-carers’ lives and caregiving experiences.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/ics.2024.15.