Introduction

During recent decades, advanced capitalist economies have seen a significant rise in precarious employment (Allmendinger et al., Reference Allmendinger, Hipp and Stuth2013; Keune, Reference Keune2013). While full-time, open-ended contracts remain common, various precarious arrangements, such as temporary employment and on-demand hiring, have emerged (Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2011; Koch and Fritz, Reference Koch and Fritz2013; ILO, 2015). Among explanations for this trend are the shift towards post-Fordist production based on flexible labour (Koch, Reference Koch and Fritz2013), deindustrialization (Eichhorst and Marx, Reference Eichhorst and Marx2015), and attempts to restore profit margins amidst competition (Landini et al., Reference Landini, Arrighetti and Bartoloni2020).

Along with different social groups, such as women and, especially, the young, migrant workers are disproportionately affected by precarious employment, also due to their over-representation in low-skill jobs (Bauder, Reference Bauder2006). However, in sectors considered well-protected, such as manufacturing, the migrants still experience higher rates of temporary employment than the natives. In Italy, for instance, data retrieved from the Labour Force Survey reveals that migrants are 1.6 times more likely than natives to have temporary contracts, with similar disparities in low-skill services.Footnote 1 Moreover, even among high-skill workers, there is evidence suggesting that migrants face a higher likelihood of labour market discrimination than the natives (Bauder, Reference Bauder2003; Tesfai, Reference Tesfai2017; Bolzani et. al, Reference Bolzani, Crivellaro and Grimaldi2021). What are the factors driving this differential treatment in terms of contracts and employment conditions between migrant and native workers? Why does this differential persist also in what are usually conceived as ‘good’ segments of the production system?

To address these questions, this article carries out a quantitative analysis focusing on the manufacturing sector in Emilia-Romagna from 2008 to 2017. Located in northeastern Italy, this region presents several advantages for the analysis at stake. First, Emilia-Romagna has been traditionally characterized by a strong specialization in high-quality manufacturing, which presently accounts for nearly 60% of the regional GDP.Footnote 2 Moreover, the region ranks second in Italy and fifth in Europe for the number of people employed in manufacturing. This productive specialization has developed alongside a structured system of industrial relations, which has received strong support from a leftist political tradition emphasizing worker representation, pro-labour policy initiatives, and fostering high unionization. According to some authors, it is precisely the peculiar combination of such a cooperative and institutionalized system of labour relations together with a robust base of industrial competences that over time has contributed to sustain the competitiveness of this region within the globalized economy (e.g. Mosconi, Reference Mosconi2023).

By positioning Emilia-Romagna as a positive benchmark with strong labour protections, our analysis can dig deeper into the structural mechanisms driving the asymmetric treatments of migrant and native workers in the labour market. Moreover, by focusing on this region, we can set a lower-bound estimate of the incidence of atypical employment among migrants. Indeed, if discrimination and precarious employment exist despite a strong economy and good industrial relations, they are likely to be even more pronounced in less regulated markets, where employer discretion is greater, collective bargaining is weaker, and informal employment is more widespread.

To identify the factors driving the higher likelihood of precarious employment among migrants, we rely on administrative data collected through the regional SILER-ARTER system on ‘comunicazioni obbligatorie’, that is, ‘mandatory communications’. This data is used to test different explanations based on human capital theory (Becker, Reference Becker1993), dual labour market processes (Piore, Reference Piore1979), the use of precarious contracts as screening devices (Baranowska et al., Reference Baranowska, Gebel and Kotowska2011; Faccini, Reference Faccini2014; Portugal and Varejão, Reference Portugal and Varejão2010), and institutional segmentation theories (Rubery and Piasna, Reference Rubery, Piasna, Piasna and Myant2017). The empirical results provide support for the latter three explanations but with important differences depending on the type of contract. Temporary contracts are common for migrants in flexible occupations with non-routine tasks, where skill screening is critical. Agency contracts, on the contrary, are more frequently used for migrants in occupations with a high incidence of repetitive tasks and in production contexts with low unionization and high employee turnover. This evidence suggests that, far from being screening devices, agency contracts are used primarily as drivers of institutional segmentation, through which employers shift production flexibility costs to less organized groups within the workforce, like migrants.

This article contributes to the literature on non-standard employment and migration in two ways. First, it complements existing empirical evidence (e.g. Dustmann et al., Reference Dustmann, Glitz and Vogel2010; Algan et al., Reference Algan, Dustmann, Glitz and Manning2010; Ronda Perez et al., Reference Ronda Perez, Benavides, Levecque, Love, Felt and Van Rossem2012; McCollum and Findlay, Reference McCollum and Findlay2015; Villarreal and Tamborini, Reference Villarreal and Tamborini2018; Krings, Reference Krings2021; Koumenta et al., Reference Koumenta, Pagliero and Rostam-Afschar2022) by digging into the mechanisms that lead to the precarious employment of migrant workers. In particular, it shows that atypical contracts for migrants are not just skill-screening tools, but mechanisms leveraging on asymmetric bargaining power among workers to create a buffer of employees most willing to take the burden of job insecurity. It also suggests that migrant precariousness is not only the result of workforce segmentation between primary and secondary segments of labour (e.g. between low- and high-skilled workers) (Piore, Reference Piore1979) but also follows from employers’ attempts to segment the workforce regardless of the skill level, while paying attention to other factors, such as the social vulnerability of the workers. On this ground, far from being limited to specific industries and occupations (e.g. low-skill services), segments of bad and precarious jobs can emerge also in relatively ‘good’ sectors of the economy (e.g. high-value-added manufacturing), with migrant workers having a disproportionately high chance of joining them.

The remaining parts of the article are organized as follows. The next section discusses the different theoretical views about the precarious employment of migrant workers. The subsequent section provides an overview of the context and the data. The penultimate section presents and discusses the empirical findings. Finally, the last section summarizes the main results and links them to the broader debate about migration and labour market segmentation.

The precarious employment of migrant workers: theoretical approaches

Evidence about the high incidence of low pay and precarious jobs among migrant workers is wide and compelling (for a recent overview, see Meardi, Reference Meardi2024). Less consensus exists, however, on the theoretical approaches that can be used to explain this evidence. Some approaches focus on supply-side factors, such as the characteristics of individual workers, while others emphasize demand-side components related to the employment strategies of employers.

Among supply-side approaches, one of the most popular is the human capital theory, which links individual labour market performance to investments in skills and knowledge (Chiswick, Reference Chiswick1978). Influenced by neoclassical economics (Becker, Reference Becker1993), human capital theorists assume that career patterns reflect worker productivity, with more educated individuals finding better-paying, stable positions. Applied to migrant workers, this theory suggests two complementary arguments. First, migrants may have lower educational qualifications than natives (Borjas, Reference Borjas1985). Second, education is often key in sorting workers into core, high-skill permanent positions as opposed to peripheral, low-skill temporary occupations (Arrighetti et al., Reference Arrighetti, Bartoloni, Landini and Pollio2022). These arguments imply that migrants, due to lower educational attainment, are less likely to secure core positions, relegating them to precarious segments of the labour market. Thus, based on this theory, the education gap is the primary factor driving the precarious employment of migrant workers, leading to the following testable prediction: migrants’ greater exposure to atypical employment compared to natives will tend to reduce when differences in human capital (e.g. levels of education) are properly accounted for.

Although widely influential, especially among policymakers,Footnote 3 human capital theory has faced criticism for its individualistic approach (Krings, Reference Krings2021). As argued by Portes (Reference Portes and Portes1995), job seekers, especially migrants, are not simply individuals with a set of skills, but also members of social groups embedded in different social contexts. These contexts, shaped by institutions and social dynamics, play a significant role in determining labour market outcomes, including the likelihood of permanent employment.

One contextual factor that may influence migrant labour market entry is the employers’ perception of workers’ backgrounds. For instance, employers may view the skills acquired by migrants through formal education as inferior to those of natives (Chiswick, Reference Chiswick1978), due to mistrust in the quality of migrants’ education or uncertainty regarding their acquisition of country-specific skills, such as language proficiency and cultural knowledge (Brekke and Mastekaasa, Reference Brekke and Mastekaasa2008). In such cases, employers may prefer to hire migrants under temporary or fixed-term contracts to screen their skills and reduce information asymmetries. As suggested by extensive literature, in the presence of uncertainty, temporary contracts allow employers to assess worker productivity and discard those who fail to meet minimum standards (Baranowska et al., Reference Baranowska, Gebel and Kotowska2011; Faccini, Reference Faccini2014; Portugal and Varejão, Reference Portugal and Varejão2010). By following this reasoning, one should also expect the incidence of precarious employment among migrants to be particularly high in those occupations where the screening of job seekers is most difficult, which leads to the following testable prediction: migrants’ greater exposure to atypical employment compared to natives is larger in those occupations where the skills of the workers are more difficult to evaluate ex-ante.

In contrast to supply-side theories, demand-side approaches, such as dual labour market theory (Piore, Reference Piore1979), emphasize the role of employers in shaping labour market inequalities. Rejecting the neoclassical assumption that labour market divisions stem from inadequate human capital, this sociological approach highlights employers as ‘architects of inequality’ (Grimshaw et al., Reference Grimshaw, Fagan, Hebson, Grimshaw, Fagan and Hebson2017: 12), shaping labour market inequalities through the creation of jobs of different quality. Employers create a primary sector of stable, well-paid jobs, and a secondary sector of unstable, poorly paid jobs (Krings, Reference Krings2021). While natives, with better social and economic resources (including social networks, see Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1995), access primary jobs, employers often rely on migrants to fill secondary positions, resulting in a ‘hierarchy of jobs’ (Piore, Reference Piore1979: 33), with distinctive job clusters that co-vary on pay, employment stability and incidence of native vs. migrant labour (Bauder, Reference Bauder2006). Based on this theory, one should thus expect job content and the related processes of occupational segmentation to be the major drivers behind migrants’ precarious employment, which in turn implies that: migrants’ greater exposure to atypical employment compared to natives will tend to reduce when differences in job-specific characteristics (e.g. occupation fixed effects) are properly accounted for.

Although dual labour market theory is still considered by many authors a useful interpretative framework to study labour market divisions in modern economies (e.g. Felbo-Kolding et al., Reference Felbo-Kolding, Leschke and Spreckelsen2019; McCollum and Findlay, Reference McCollum and Findlay2015; MacKenzie and Forde, Reference MacKenzie and Forde2009), it has been criticized in particular for its distinction between primary and secondary sectors considered ‘too simplistic as segmentation lines in “postindustrial” economies are more complex’ (Krings, Reference Krings2021: 529), and for its unique focus on decisions taken by employing organizations. While early dualist theorists (e.g. Doeringer and Piore, Reference Doeringer and Piore1971) ‘explained segmentation mostly through the technical features of the production process and the strategic importance for the firm of the skills they required’, in modern economies, segmentation is often the result of the complex interaction between labour supply and demand (Grimshaw et al., Reference Grimshaw, Fagan, Hebson, Grimshaw, Fagan and Hebson2017: 13). In particular, the employers’ decisions about the type of jobs they offer are not independent of the characteristics of the labour force they serve (Rubery, Reference Rubery2007).

There have been several attempts to expand the scope of dualization theories in different directions (Marsden Reference Marsden1999; Rubery Reference Rubery1978, Reference Rubery2007; Sengenberger Reference Sengenberger and Wilkinson1981; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson1981). This led to the emergence of an alternative approach usually known as institutional segmentation theory, diverging from the original perspective along two main lines. First, it considers more explicitly segmentation processes occurring on both sides of the labour market. Indeed, while employer strategies regarding the selection, reward, and retention of workers can certainly play a key role in creating segmented job offers (Osterman, Reference Osterman, Kerr and Staudohar1994), these strategies are also influenced by the characteristics of the labour supply (Rubery & Piasna, Reference Rubery, Piasna, Piasna and Myant2017). If the labour force is divided and socially stratified, for instance through divides between natives and migrant workers as well as between incumbent (stable) and external (rotating) employees (e.g. in firms with high employee turnover), employers can be at ease in exploiting specific vulnerable groups (i.e. migrants) as sources of flexible and low-paid labour, ultimately rising their profits. The bargaining power of employers may also be favoured by the existence of high search costs for some specific social groups (e.g. migrants’ limited knowledge of job search channels), which may induce firms to practice monopsonistic discrimination over wages and contracts (Hirsch and Jahn, Reference Hirsch and Jahn2015). These opportunities should in turn imply that, for any skill level, precarious contracts are widely used by the employing organizations and also that migrants are the best candidates to signing into them.

Second, alongside divisions in the labour supply, the extent to which jobs are segmented also depends on the institutions regulating the labour market. For instance, in contexts where workers are organized into powerful unions, employers are more likely to offer good jobs (Grimshaw et al., Reference Grimshaw, Fagan, Hebson, Grimshaw, Fagan and Hebson2017). On the contrary, when similar collective voice channels are absent, employers enjoy greater bargaining power and may decide to offer jobs that are more precarious and of lower pay, irrespective of the skills or productivity of the workers (Rubery, Reference Rubery1978).Footnote 4 In some cases, unions can themselves be a source of job segmentation, especially when they differentiate the level of protection among insider and outsider groups of workers (Lindbeck and Snower, Reference Lindbeck and Snower1988). A similar segmentation effect can also be introduced by the way in which labour law is designed, for instance, when it fails to align protections for core and atypical workers (Deakin, Reference Deakin2013). In addition, regulatory frameworks can provide employers with alternatives to standard contracts by expanding atypical work arrangements, increasing reliance on temporary and agency work. These dynamics are especially pronounced in labour markets with weak unions and high proportions of vulnerable workers (Benassi and Dorigatti, Reference Benassi and Dorigatti2020). All these arguments can be summarized in the following testable prediction: migrants’ greater exposure to atypical employment compared to natives holds across occupations and is larger in those institutional contexts where workers enjoy weaker bargaining power (e.g. in presence of weak unions and/or high employee turnover).

To summarize, explanations for the high incidence of precarious employment among migrants vary. While human capital gaps and skill uncertainty are important, demand-side factors, such as occupational segmentation and labour market institutions, also play crucial roles. These dynamics suggest that precarious employment among migrants is not confined to low-skill jobs but extends to good sectors of the economy, deepening their social and economic marginalization.

Institutional context and data

These different theories are brought to the data by using administrative information covering the manufacturing sector of the Emilia-Romagna region. In recent years, this region, like many other territories in Italy, has been intersected by two important transformations. First, since the mid-1990s, the region has attracted a growing number of migrant workers, whose employment in manufacturing has both met labour demands and increased workforce diversity, challenging traditional union representation (Marino, Reference Marino2012). Second, during the same period, the region has gone through important processes of country-wide institutional reforms, which have profoundly changed the functioning of many parts of the economy, including the labour markets. These reforms were guided by attempts to reduce the rigidity of standard forms of employment, to meet the increasing requests for flexible and agile production inputs on the side of the firms. The first step was the liberalization of fixed-term contracts (‘contratti a tempo determinato’), which allowed employers to hire workers on a temporary basis, but still maintaining some level of job security through legal limits on contract renewals, durations, and employer responsibilities (Daruich et al. Reference Daruich, Di Addario and Saggio2023). Later, a further step was the introduction of agency contracts (‘contratti interinali’). Unlike fixed-term contracts, these contracts involve a third-party employment agency, which formally hires the workers and allocates them to firms. Their key advantage is the greater flexibility in workforce management, as firms can hire and release workers without direct legal obligations, shifting administrative and contractual responsibilities to the agency. While agency workers are granted certain protections – such as social security contributions and inclusion in collective agreements – their employment is structurally more precarious, as it depends on the availability of new assignments. Over time, the use of these contracts has risen considerably, especially after the removal of the firm’s formal obligation to motivate their use.Footnote 5 As a result, agency contracts have increasingly been perceived as close substitutes for temporary arrangements by firms looking for sustained sources of production flexibility, with the additional advantage that when hiring external workers these firms could search into a pool of workers who enjoyed relatively weak support from the unions, with important advantages in bargaining power (Benassi and Dorigatti, Reference Benassi and Dorigatti2020).

The combination of rising migrant inflows and sustained labour market liberalization has brought new challenges for the cooperative socio-economic milieux that characterized the Emilia-Romagna Region for decades. Indeed, despite its traditional and politically endorsed focus on high-quality employment, these developments have exposed the workforce to emergent patterns of social segmentation, with migrants being particularly vulnerable to heightened risks of job insecurity. This paradox of precariousness within a region renowned for its cohesive labour relations underlines the need to explore in greater detail the mechanisms driving such disparities.

To this aim, we carry out an empirical analysis relying on administrative data collected by Italian local public administrations called ‘Regions’ (i.e. first-level constituent entities corresponding to the second NUTS administrative level) through a system called ‘comunicazioni obbligatorie’, that is, ‘mandatory communications’. Regions are responsible for so-called ‘active labour market policies’ and thus required to create a digital platform through which private sector employers must communicate a given set of information concerning the firm, the employees, and the contractual bases every time a given case of contract transformation occurs. The latter include cases of hiring, dismissal, resignation, contract extension, and conversion, as well as main changes in contractual bases and characteristics. In the case of Emilia-Romagna, this electronic tool is called the SILER-ARTER system, that is, ‘Sistema Informativo Lavoro – Emilia-Romagna’. The resulting dataset thus potentially encompasses all employment relationships associated with events of contract transformation that took place from January 2008 to December 2017, in the private sector of the Emilia-Romagna region, excluding agriculture. For each event, data includes information about the contractual arrangement (type of contract, start and end date, days of work), the occupational code of the employee (6-digit ISCO code), some individual information about the worker (sex, nationality, educational attainment) as well as the identifier of the employer.Footnote 6

Our focus is on contract activations for open-ended, temporary, and agency contracts. To enrich this dataset, we incorporate firm-level economic and financial data (e.g. industry) from the Aida-BVD archive, which compiles Italian firms’ balance sheets from chambers of commerce for the same period (2008–2017).

The unit of observation in our analysis is the activation of a contractFootnote 7 and the dependent variable is the contract type. The latter can take one of three values: 1 for open-ended contract; 2 for temporary contract; and 3 for agency contract. These three types of contracts cover 92.83% of all activations, the remaining ones being associated with apprenticeship contracts and job placement (3.87%) and parasubordinate work (3.30%).Footnote 8

The key independent variable at the individual level is the nationality of the worker. One dichotomous variable is created: ‘migrant’ taking the value equal to 1 if the worker has a non-EU nationality, and 0 otherwise. The main reason for adopting this classification is that we want to include among migrants those workers who come from relatively poor countries and can thus be reasonably considered vulnerable actors. Partly in support of this choice, we report that in our classification, the most common nationalities among migrant workers include Moroccan (15.38%) and Albanian (9.73%).Footnote 9 At the same time, our choice excludes the migrant status low-skill workers coming from laggard EU member states, such as, for instance, Romania (which contributes with a share of 15.13% of workers). For this reason, we run several robustness checks to compare alternative ways of classifying migrant workers, and the main results do not change (except for temporary contracts, see below).

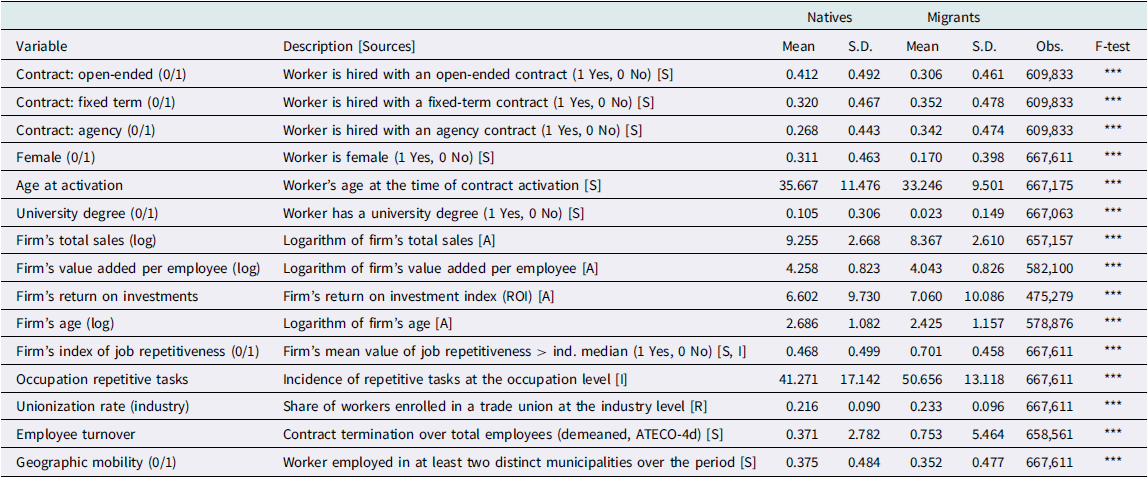

Table 1 reports some descriptive statistics for the main variables included in the analysis. In line with our expectations, fixed-term and agency contracts are more frequently used to hire migrant workers than the native ones (35% vs. 32% and 34% vs. 27%, respectively). This result confirms the greater exposure of foreign workers to atypical forms of employment, which also translate into contracts that are on average, more frequent and shorter (see Table B.1 in the online Appendix). Interestingly, migrant workers are on average younger, less educated, and more likely to be male compared to native workers, which suggests the existence of gendered social norms driving the participation of these distinct social groups in the workforce. Overall, this preliminary evidence is consistent with previous evidence documenting patterns of precarious employment among migrant workers. In the next section, we will rely on a multivariate analysis to explore whether the mechanisms driving this result align with either of the theoretical explanations discussed above.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Source: Authors’ own elaboration on SILER (S), AIDA (A), ICP (I), and RIL (R) data. Description reports also the data sources used to compute the variables. The last column reports the result of an F-test on the difference between the mean values for migrant and native workers. * 10%; ** 5%; *** 1%.

Results

Baseline

We begin by considering the baseline regression model:

where subscripts i, o, f, s, p, and t denote the individual, occupation, firm, sector, province, and time, respectively; Y i is the contract type; migrant i is a dummy variable for migrant status (see above), Ai is a vector of individual-level controls, Bf is a vector of firm-level controls; and finally, ω o, σ s, π p, and τ t are a battery of occupation, sector, province, and time fixed effects. The model is estimated through a series of multinomial logistic regressionsFootnote 10, whose outcomes are displayed in Table 2. The reported coefficients are marginal effects; that is, they represent the difference in probability of engaging in either an open-ended, fixed-term, or agency contract associated with being a migrant worker compared to a native one, which is the benchmark category.

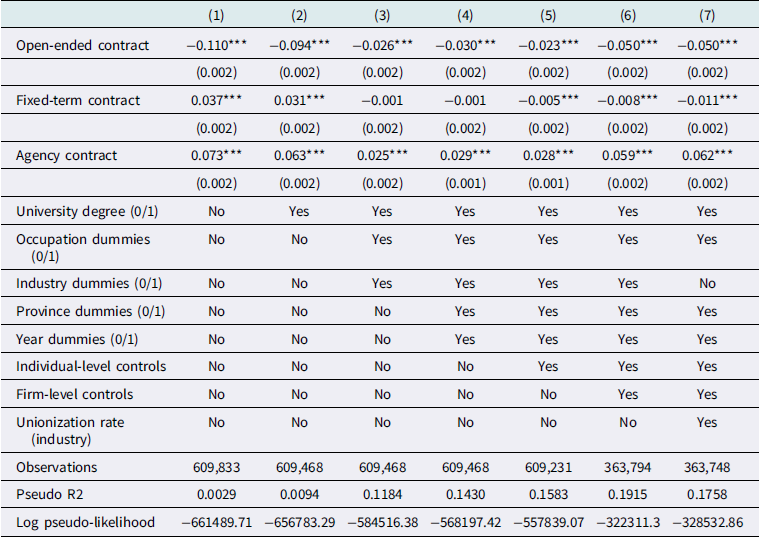

Table 2. Marginal effects of migrant status, multinomial regression

Source: Authors’ own elaboration on SILER and AIDA data. Robust standard errors clustered at the individual level in brackets. Multinomial-logit model, marginal effects. Dependent variable: type of activation of a contract: 0. Open-ended contract (baseline), 1. Fixed-term contracts, 2. Working agency contracts. Individual-level controls include: male (0/1), age at activation. Firm-level controls include: logarithm of total sales, return on investment index, logarithm of value added per employee, logarithm of firm age, index of job repetitiveness (dummy: 0 under the industry median, 1 over the industry median). Observation unit: activation of a type of contract of a worker in a firm. Significance levels: * 10%, ** 5%, *** 1%.

In column (1), we present the results of an unconditional regression model with no controls. Being a migrant worker raises the probability of being hired with either a fixed-term or an agency contract, while it reduces the chances of being hired with an open-ended one. This aligns with expectations, though it does not decisively support either hypothesis: employers may prefer to hire migrant workers with an atypical contract due to their lower educational attainment, the perceived ‘uncertainty’ in their skills, requiring more scrutiny before regular hiring, or because of their lower bargaining power and thus the possibility to reduce wages. To start discerning among these alternative explanations, in column (2), we introduced the education level among regressors, categorized as a binary variable equal to 1 for workers with a university degree or higher education title, and 0 for the others.Footnote 11 The effect of being a migrant worker remains the same for all contract types, although the magnitude of the coefficients slightly reduces. This result suggests that differences in educational attainment between migrant and native workers are relevant but do not entirely explain the variance in the probability that these distinct classes of workers are offered an atypical contract.

In the next columns, we introduce additional controls. In column (3), we add dummy variables for ISCO occupation at 3-digit and ATECO industry at 2-digit (equivalent to NACE). In column (4), we include year and province fixed effects. In column (5), we add controls for individual worker characteristics, including the binary gender variable (1 for male, 0 for female) and the age of the worker at the time of contract activation. Interestingly, we observe that, once occupation and industry-fixed effects are included, the magnitude of all coefficients significantly reduces, and for fixed-term contracts, the estimated effect becomes either not significant or very close to zero. This result suggests that perhaps, not surprisingly, processes of occupational segmentation explain a large part of the sizable effects estimated in the unconditional analysis (column 1). It also suggests the existence of an interesting asymmetry between the two types of atypical contracts: while (keeping the other variables constant) being a migrant worker does not raise the likelihood of being hired with a fixed-term contract, for agency contracts, the effect is positive and significant. Thus, for the latter type of contract, there still is some unobservable factor associated with being migrant workers that partly explain a larger use of this atypical contract and that can be linked neither to differences in human capital nor to a process of pure occupational segmentation (indeed, both factors are controlled for in the estimates).Footnote 12

In columns (6) and (7), we further refine the analysis by incorporating an additional set of control variables. In column (6), we control firm-specific characteristics, including the logarithm of total sales, the return on investments, the logarithm of labour productivity (calculated as the ratio between added value and the number of employees in the last available year in the AIDA dataset), the logarithm of the age of the firm, and an index of job repetitiveness. The latter is computed exploiting occupation-level information contained in the 2012 ICP dataset (Indagine Campionaria sulle Professioni), a survey conducted by INAPP (Istituto Nazionale per l’Analisi delle Politiche Pubbliche) in collaboration with ISTAT (Istituto Nazionale di Statistica) reporting (among other things) how often an occupation requires workers to perform repetitive tasks.Footnote 13 We computed the mean value of task repetitiveness for the occupations activated by the firm in the reference period and then built a dummy variable that takes the value equal to 1 if the firm has a mean value of task repetitiveness larger than the median of its (2-digit) industry (0 otherwise). Since job repetitiveness has been shown to increase the use of atypical contracts (Cattani et al., Reference Cattani, Dughera and Landini2023), we expect this index to control for organizational drivers of atypical employment at the firm level. Finally, in the last column, we control more explicitly for institutional factors that may affect the use of atypical contracts by replacing industry-fixed effects with the sector-level degree of unionization. The latter is calculated using information from the 2015 wave of the RIL survey (Rilevazione Imprese e Lavoro), which was carried out by INAPP on a representative sample of non-agricultural firms in Italy. Among other things, the survey asks to firm how many employees are enrolled in a trade union, and these data are aggregated using sample weights at the sectoral ATECO-2-digits level as a percentage of unionized workers in the sector. Such data is then merged with the SILER-ARTER database, exploiting information about the industry in which the firm activating the contracts is operating. This additional set of baseline regressions provides broadly consistent results. Although due to missing information for the variables computed at the firm level, the total number of observations in some specifications reduces, the coefficient for migrant workers remains positive and significant only for agency contracts.Footnote 14 In particular, in the most complete specifications, we find that being a migrant worker raises the probability of being hired with an agency contract by about 2.0–5.8 percentage points (depending on the model).Footnote 15

Overall, the baseline regressions consistently point out that migrant workers have a higher probability of being involved in precarious employment through either the fixed-term or agency contract than the natives. While for fixed-term contracts this effect seems to be explained mainly by a process of occupational segmentation (i.e. migrant workers find more frequent employment in occupations and industries that make more extensive use of fixed-term contracts), for agency contracts the status of migrant worker seems to exert an independent effect.Footnote 16 Theoretically, as argued above, this independent effect could be either a consequence of the employers finding it challenging to evaluate the skill level of migrant workers (i.e. screening hypothesis) or follow from attempts to reduce labour costs by exploiting the lower bargaining power of this specific labour segment (i.e. institutional segmentation). To further explore these alternative explanations, in the following section, we carry out some additional tests to explore the heterogeneity of our main effect across distinct worker/occupation-specific factors and institutional dimensions.

Heterogeneity of the main effect

To gather more evidence regarding the motivation behind the use of various types of employment contracts, we conduct a set of empirical exercises where we check how the association between the status as a migrant worker and the engagement with open-ended, fixed-term, and agency contracts varies depending on: (a) the task profile of the occupation, (b) the degree of industry-level unionization, and (c) the incidence of workers’ turnover at the firm level. For each of these dimensions, we run a set of multinomial logistic regressions where we interact these variables with migrant status. Formally, the estimated model is:

where x j denotes the heterogeneity dimension we focus on, with j being the occupation, industry, or firm depending on the model. We expect that potential changes in the effect of being a migrant worker on the probability of precarious employment for different levels of x j can help disentangle the importance of our different theoretical hypotheses. In particular, this is true for the screening and institutional segmentation hypotheses, which hinge upon task characteristics (the former) and worker bargaining power (the latter) as factors driving the use of atypical contracts.

We start by considering the screening hypothesis. According to this theory, atypical contracts are used to screen the skills of the workers before moving into permanent employment. It follows that temporary positions should be particularly common in occupations where such skills are difficult to assess, such as jobs with a high incidence of non-routine tasks. At the same time, while keeping other individual and firm-level characteristics constant, temporary contracts should become less frequent in occupations where tasks are more repetitive because in those cases, the skills required to perform the job can be more easily evaluated. Moreover, if the uncertainty surrounding the skills of migrant workers holds true, we should also expect that the differential in the probability of being hired through, say, an agency contract tends to reduce as the skills of the workers become more easily assessable, that is, when moving from non-routine to routine occupations.

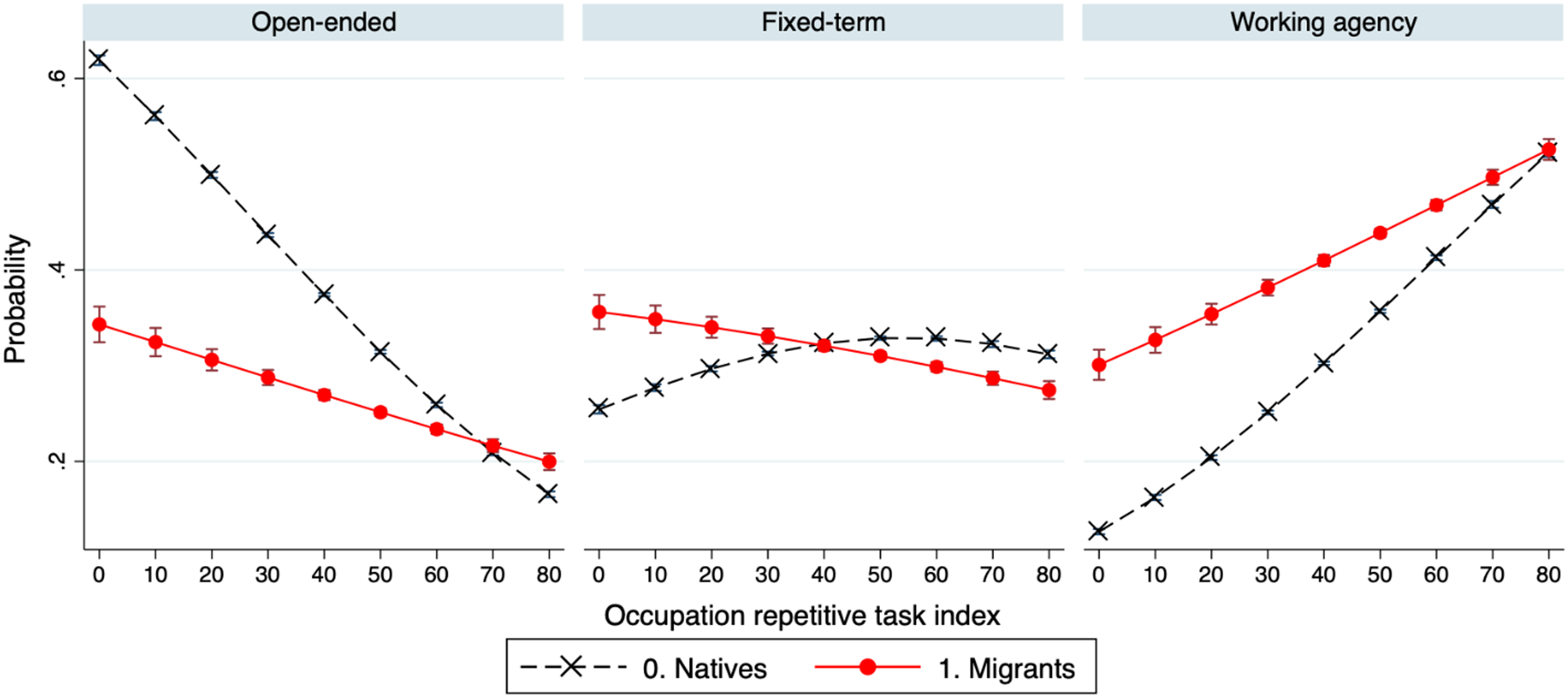

Figure 1 explores this possibility by reporting the estimated margins for the interaction term between migrant workers and different levels of task repetitiveness within occupations. Task repetitiveness is computed at the occupation level using the ICP dataset described above (i.e. considering the specific occupation in which the worker is employed). The first panel reports the marginal effects on the probability of being hired with an open-ended contract, while the second and third panels focus on temporary contracts and agency contracts, respectively. In general, confirming our baseline results, migrant workers have a higher (lower) probability than natives of obtaining an atypical (permanent) contract. Also, in this case, however, there exists an important difference between the two types of atypical employment. For fixed-term contracts, partially in line with the screening hypothesis, the probability of their use to hire a migrant worker tends to reduce with the incidence of repetitive tasks and so does the probability gap between migrant and native workers (eventually becoming negative in highly routinized occupations). For agency contracts, on the contrary, a similar reduction in the probability gap emerges alongside the increasing use of such contracts as occupations become more routinized, openly contradicting the theoretical predictions based on the screening hypothesis. Thus, although these results partially confirm that the larger use of fixed-term contracts for migrant workers can be explained through the combination of occupational segmentation and skill screening, for agency contracts, the logic behind their use seems inconsistent with screening processes. Rather, their use seems to be driven by other factors, among which the bargaining power of the workers can be particularly relevant.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of migrant vs. native status for different degrees of task repetitiveness.

Notes: Authors’ own elaboration on SILER, AIDA, and ICP data. Multinomial-logit model, marginal effects. Dependent variable: type of activation of a contract: 0. Open-ended contract, 1. Fixed-term contracts, 2. Agency contracts. Individual-level controls: university degree (0/1), male (0/1), age at activation. Firm-level controls: logarithm of total sales, return on investment index, logarithm of value added per employee, logarithm of firm age, firm index of job repetitiveness (dummy: 0 under the industry median, 1 over the industry median), occupation repetitive tasks index. Additional controls: industry dummies (ATECO2d), year dummies, province dummies. Observation unit: activation of a contract type. Estimates show the marginal effect of migrant status for different levels of task repetitiveness at the occupation level. Full model outcomes including number of observations and pseudo R2 are reported in Table B.3 (column 1) in the online Appendix.

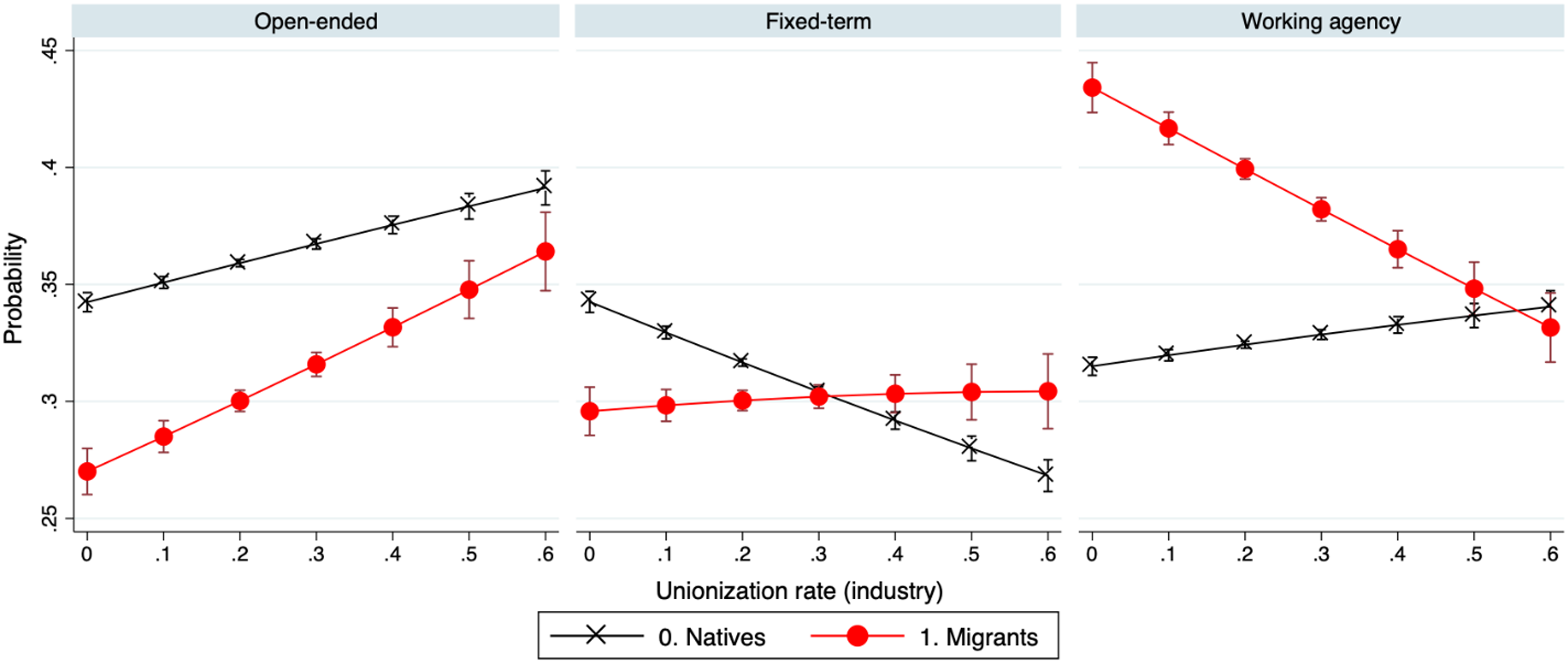

To check whether this is indeed the case, in the second empirical exercise, we shift our focus to the role of industry-level unionization. According to the institutional segmentation hypothesis, one of the reasons why migrant workers are more likely to be engaged in atypical employment is that, compared to natives, they have low bargaining power. Especially in sectors where the unionization rate is small, this condition exposes them to the strategies of work precarization and externalization pursued by the employers, which tend to target the most vulnerable segments within the workforce, including migrants. If that is the case, the prediction originating from this theory is rather straightforward: we should observe the gap in the probability of atypical employment between migrant and native workers to reduce as the degree of unionization rises.

Figure 2 verifies this hypothesis by reporting the estimated effect of migrant workers for different degrees of industry-level unionization. For native workers, the incidence of organized labour plays some role in determining their probability of employment with different types of contracts. Specifically, it increases the likelihood of having an open-ended contract compared to a fixed-term contract. For migrants, this effect seems even more pronounced and related especially to the use of agency contracts. In particular, while in highly unionized sectors, the probability that a migrant worker is hired with an agency contract is not significantly different from that of natives and this is mirrored by easier access to open-ended contracts; in low unionized sectors, the probability of migrant employment with an agency contract significantly rises. These trends suggest that as the degree of unionization reduces, employers tend to switch from employing migrant workers with an open-ended contract to employing them through external agencies (no relevant difference emerges instead with respect to fixed-term contracts). Such a process of targeted externalization is indeed consistent with the predictions based on institutional segmentation theory, with employers trying to exploit the lack of collective voice to shift the burden of precarity on the weakest social segments, such as migrants.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of migrant vs. native status for different levels of industry unionization.

Notes: Authors’ own elaboration on SILER, AIDA, and RIL data. Multinomial-logit model, marginal effects. Dependent variable: type of activation of a contract: 0. Open-ended contract, 1. Fixed-term contracts, 2. Working agency contracts. Individual-level controls: university degree (0/1), male (0/1), age at activation. Firm-level controls: logarithm of total sales, return on investment index, logarithm of value added per employee, logarithm of firm age, firm index of job repetitiveness (dummy: 0 under the industry median, 1 over the industry median), unionization rate (industry). Additional controls: occupation dummies (ISCO3d), year dummies, province dummies. Observation unit: activation of a contract type. Estimates show the marginal effect of migrant status for different levels of unionization rate at the industry level. Full model outcomes including number of observations and pseudo R2 are reported in Table B.3 (column 2) in the online Appendix.

Although unionization rates at the sector level can capture industry-wide forms of collective voice among workers, in many contexts, the bargaining power of employees can vary considerably across firms, even within the same sector. For instance, in firms with institutionalized forms of shop-floor representation, employees may exert greater influence on working conditions, including those related to the use of distinct employment contracts.Footnote 17 Unfortunately, however, our administrative data does not allow us to observe the presence of unions at the firm level. Still, we can exploit some alternative indexes as proxies of workers’ bargaining power across firms. One such index is the degree of employee turnover. Indeed, an extended literature documents that in firms with a high incidence of employee terminations per year, incumbent workers typically experience higher coordination costs and weaker voice mechanisms to affect employment strategies (e.g. Iverson and Currivan, Reference Iverson and Currivan2003). Moreover, new hires are exposed to a high chance of substitution and replacement, which reduces even further their bargaining power in the process of contract negotiation. It follows that if institutional segmentation is the main driver behind the use of atypical contracts, especially agency ones, we should expect the positive gap in their use between migrant and native workers to increase in firms with a higher incidence of employee turnover.

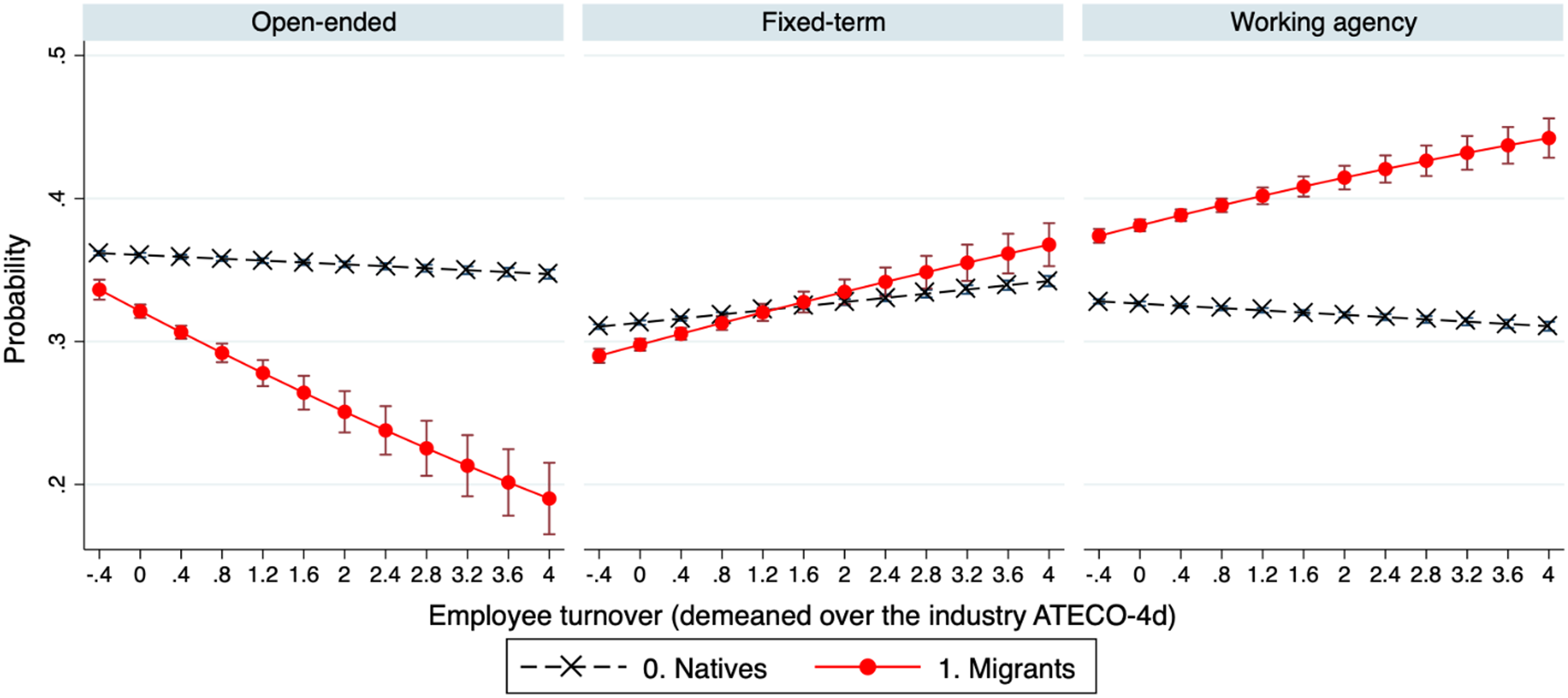

To test this prediction, we extend our baseline analysis by adding employment turnover (computed as the number of contract terminations over total employees) among the control variables. To fully grasp the heterogeneity of bargaining power across firms, we compute this variable while subtracting for each firm its corresponding industry mean (2-digit ATECO). Then, we interact such a demeaned variable with the migrant status variable and plot the estimated marginal effects for different levels of employment turnover. The results are reported in Figure 3. For fixed-term contracts, employee turnover affects only marginally the coefficient associated with migrant status, whereas for agency contracts, the size of the coefficient is significantly larger the higher the degree of employment turnover. Moreover, such an increase goes together with a widening gap in the estimated effects between migrant and native workers. This result further confirms that bargaining power and institutional segmentation are significant factors driving the use of these types of atypical contracts.Footnote 18

Figure 3. Marginal effects of migrant vs. native status for different levels of employee turnover.

Notes: Authors’ own elaboration on SILER, AIDA, and RIL data. Multinomial-logit model, marginal effects. Dependent variable: type of activation of a contract: 0. Open-ended contract, 1. Fixed-term contracts, 2. Working agency contracts. Individual-level controls: university degree (0/1), male (0/1), age at activation. Firm-level controls: logarithm of total sales, return on investment index, logarithm of value added per employee, logarithm of firm age, firm index of job repetitiveness (dummy: 0 under the industry median, 1 over the industry median), employee turnover (demeaned over the sector ATECO-4d). Additional controls: occupation dummies (ISCO3d), industry dummies (ATECO2d), year dummies, province dummies. Observation unit: activation of a contract type. Estimates show the marginal effect of migrant status on different levels of employee turnover. Full model outcomes including the number of observations and pseudo R2 are reported in Table B.3 (column 3) in the online Appendix.

Conclusion

The atypical employment of migrant workers is a widely investigated topic that has attracted the attention of scholars and policymakers alike. While previous studies focused on the concentration of migrants into sectors that are usually characterized by poor and precarious working conditions (e.g. low-skill services), this article investigated migrant atypical employment in the manufacturing industry, which is usually considered a source of good job opportunities. Moreover, the article focused on an Italian region, that is, Emilia-Romagna, that has historically developed a specialization in high-quality productions, supported by a structured system of industrial relations. The fact that even in a similar productive context migrant workers face a disproportionally higher likelihood than natives to be hired with an atypical contract (either fixed-term or agency contract) needs an explanation, which we provided in this article.

By looking at the previous literature, we compared four theoretical approaches that account for the high incidence of precarious employment among migrants: a) the human capital theory (Becker, Reference Becker1993), dual labour market processes (Piore, Reference Piore1979), the screening hypotheses (Baranowska et al., Reference Baranowska, Gebel and Kotowska2011; Faccini, Reference Faccini2014; Portugal and Varejão, Reference Portugal and Varejão2010), and institutional segmentation theories (Rubery and Piasna, Reference Rubery, Piasna, Piasna and Myant2017). We tested these theories on a rich set of administrative data with information at both the individual and firm levels. In terms of the empirical model, we employed a multinomial logistic regression that was integrated with an analysis of heterogeneity aimed at investigating changes in the main effect of interest across types of firms, industries, and occupations. Although we cannot fully address causality and sorting issues, the empirical analysis was enriched by a set of robustness checks, which strengthened the consistency of our baseline findings.

Overall, the results of our empirical analysis provide a composite mix of evidence. While the baseline estimates provide weak support for the human capital hypothesis, other empirical exercises reveal that dual labour market processes, the screening hypothesis, and the institutional segmentation theory can play a role. There is, however, an important difference: dual processes and screening mechanisms seem to drive the atypical employment of migrant workers, especially through fixed-term contracts; on the contrary, the hiring of migrants through agency contracts seems to be driven primarily by processes of institutional segmentation. Through the latter, employers can exploit divisions and social stratifications that are present within the workforce to obtain flexible and relatively low-paid labour, ultimately raising their profits.

The existence of this difference in the use of temporary and agency contracts has important implications for the design of labour market policy and institutions. Indeed, provided that in general, any type of atypical employment has been shown to have high social costs (Bryson and Harvey, Reference Bryson and Harvey2000; Clarke et al., Reference Clarke, Lewchuk, de Wolff and King2007; Lewchuk, Reference Lewchuk2017; Moscone et al., Reference Moscone, Tosetti and Vittadini2016; Kalleberg, Reference Kalleberg2018; Aleksynska, Reference Aleksynska2018), our findings suggest that each of these contracts is likely to generate private benefits that are very different in nature. Fixed-term contracts can help segment the workforce between primary and secondary jobs, while at the same time, reducing the uncertainty surrounding the skills and competences of migrant workers. Agency contracts are instead used primarily to exploit the weak bargaining power of migrants and thus increase profits. In this sense, agency contracts seem to be characterized by a more marked class-based and conflictual underpinning than fixed-term contracts, with all the social inefficiencies that this may imply (for instance, agency contracts can be overused since their social costs are not fully internalized by the employing firms).

When dealing with the design of labour market policy and institutions, the difference between these two types of contracts needs to be adequately considered. Since the mechanism behind the decision to hire a migrant worker with a fixed-term contract is primarily linked with problems of occupational segmentation and information asymmetry, any intervention that helps curb such processes can contribute to re-aligning migrant and native exposure to temporary employment. These interventions may range from the introduction of quality standards to ascertain the formal qualifications of migrant workers to broader interventions targeting labour market processes that, independently from the formal qualifications of the workers, can reduce the firm’s incentives to segment its workforce. With respect to agency contracts, instead, policymakers need to explicitly acknowledge the role of employment agencies as active agents in transforming the labour markets (Fudge and Strauss, Reference Fudge and Strauss2014). On this ground, socially efficient use of these contracts must be obtained through actions aimed at rebalancing the bargaining power of migrants vis-à-vis their employers and agency contractors. In particular, this objective can be achieved in two ways: either by introducing (or in the Italian case, re-introducing) further constraints on the use of agency contracts (for instance, by requiring justifications for their adoption in the place of standard fixed-term or open-ended contracts) or by strengthening the overall penetration of trade unions within industries, having a specific target on the collective representation of migrant workers. In addition, policymakers could also consider a range of labour law reforms aimed at ensuring parity of treatment in terms of rights and working conditions between agencies and core workers.