1. Introduction

Languages in contact commonly leave an imprint on one other. The most straightforward of these imprints to identify is what Matras and Sakel term MAT(ter)-borrowing, defined as “when morphological material and its phonological shape from one language is replicated in another language” (Sakel Reference Sakel, Matras and Sakel2007: 15). MAT-borrowings (lexical borrowing, code-switching), therefore result in clearly identifiable lexical items of one language (the donor language) being used in utterances of another language (the recipient language). See, for example (1)–(2), which illustrate English MAT-borrowings in Guernésiais, the Norman variety spoken in Guernsey, one of the British Channel Islands (see Jones Reference Jones2024).Footnote 1

-

(1) J’avais ma scarf passequ’il’tait gniet ‘I had my scarf because it was night-time.’

-

(2) All’a meetaï aen haomme ‘She has met a man.’

This stands in contrast with PAT(tern)-borrowing, defined as “where only the patterns of the other language are replicated – i.e. the organisation, distribution and mapping of grammatical or semantic meaning, while the form itself is not borrowed” (Sakel Reference Sakel, Matras and Sakel2007: 15).Footnote 2 As will be demonstrated in the present study, PAT-borrowing does not involve any such incorporation of “other language” material but rather results in the reshaping of existing structures of the recipient language on the model of the donor language (see §3).

While many languages in contact display evidence of both types of borrowing, some display a propensity towards only one. Aikhenvald (Reference Aikhenvald1996) for example, describes how Tariana, spoken along the Vaupés river in Amazonas, Brazil, has been dramatically restructured on the model of the Tucanoan languages of the same area almost entirely without lexical borrowing of any kind (cf. also Kroskrity Reference Kroskrity1993; Thomason Reference Thomason2007; Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald, Aikhenvald and Dixon2006: 40) although, as Sakel notes (Reference Sakel, Matras and Sakel2007: 26n2), the inverse situation of MAT-borrowing without any PAT-borrowing is relatively rare. Commenting on this dichotomy, Matras and Sakel (Reference Matras and Sakel2007: 841–842) state that “Disentangling the two types of processes, MAT and PAT, seems essential if one is to try and compare the cross-linguistic outcomes of contact induced change”. In an attempt to contribute to such disentangling by exploring and further informing this dichotomy, I have undertaken a detailed study of the linguistic outcomes of language contact in Guernésiais, drawing on original data from many years of extensive fieldwork. The results obtained for Part I of this study (which examined MAT-borrowing) are presented in Jones (Reference Jones2024). The present analysis (which represents Part II of the study) complements and completes that work by presenting a detailed examination of PAT-borrowing in Guernésiais.

1.1 Guernsey

Guernsey’s Norman speech community has been in contact with English since the installation of a small garrison on the island to protect against the threat of a French attack after the Channel Islands became formally annexed to the English Crown in 1259. Though initially small, the garrison grew steadily as Guernsey’s strategic significance as a military base increased when England became more involved in wars outside its shores. During the Napoleonic Wars, for example, almost 6,000 men were stationed in the island, whose local population at the time was recorded as 16,155: the troops inevitably brought tradespeople and other locals into contact with English. From the nineteenth century, trade with England, in particular the development of the horticultural industry, integrated Guernsey’s economy firmly with that of the UK and the improvement of regular communication by sea allowed tourism to be set on a serious footing, bringing thousands of people from the UK to the Channel Islands each year. Language contact was accompanied by cultural contact, with English customs being adopted, many local streets being renamed (from French to English) and English influence becoming increasingly visible in Guernsey’s architecture. During the Second World War, the evacuation to the UK of over half of Guernsey’s population prior to the island’s occupation by German military forces also brought islanders – very abruptly – into contact with English, with many of the evacuated children growing up with English, rather than Norman, as their mother tongue. Since the War, immigration from the UK, associated with the expansion of Guernsey’s off-shore finance industry, now its largest employer, has resulted in UK-born individuals representing nearly one quarter of Guernsey’s population.Footnote 3 Today, Guernésiais is at an advanced state of language shift. Current estimates put the number of speakers at no more than a few hundred (less than 0.5% of the island’s 63,448 residents), most of whom are elderly and all of whom are fluent in English (see, among others, Jones Reference Jones2008, Reference Jones2015, Reference Jones2024).Footnote 4 It goes without saying therefore that English now dominates every domain of island life.

Although French served as the de facto standard language of the Channel Islands up until the twentieth century,Footnote 5 enjoying exclusive use in so-called “High” domains from the Middle Ages right up until the time when English started to predominate (Brasseur Reference Brasseur1977; Jones Reference Jones2001, Reference Jones2008, Reference Jones2015), it has always functioned as an exoglossic standard. Today, French remains functionally differentiated from both Norman and English, being reserved for formulaic, ceremonial usage, such as for the opening prayers and oral voting in meetings of the Channel Island parliamentary assemblies. For most contemporary speakers of Guernésiais, therefore, the linguistic relationship with French is akin to that which one would have with a “foreign” language. Like other British citizens, islanders will have encountered French via the education system, albeit generally a few years earlier than in the UK, but they do not speak it natively nor, for the most part, does French have much relevance for their daily lives.Footnote 6 For this reason, French does not play a significant role in contact-induced language change in the Channel Islands.

1.2 PAT-borrowing

MAT-borrowing can attract value-judgements, such as accusations of speaking “darn ’leth Gàidhlig, darn ’leth Beurl” (‘half-Gaelic, half-English’) (Dorian Reference Dorian1981: 98) (cf. King Reference King2001: 195). This may lead to speakers consciously self-correcting or calling attention to the fact that they are using other-language lexical material, as illustrated by the following examples of English MAT-borrowings in Jèrriais, which is spoken in Jersey, Guernsey’s Channel Island neighbour. In (3), the MAT-borrowing from English is followed by its equivalent in Jèrriais and, in (4), it is followed by a metalinguistic comment (Jones Reference Jones2005a: 13). In other words, when they MAT-borrow, speakers seem to be aware that they are not keeping their languages materially separate.

-

(3) Tout l’monde pâlait l’Jèrriais dans l’playground, dans l’bel dé l’école ‘Everyone spoke Jèrriais in the playground.’

-

(4) Pèrsonne n’voulai(en)t l’acater sinon les pèrsonnes tchi voulaient changi l’affaithe en flats, comme qué nou dit ‘No-one wanted to buy it apart from the people who wanted to change the thing into flats, as we say.’

In contrast, PAT-borrowing does not involve the incorporation of any identifiable “other language” material and it is therefore arguably more “invisible” to speakers. Indeed, since this form of borrowing allows speakers not to deviate from the language choice parameter which they, their interlocutor or the sociolinguistic context set for the conversation, it is usually less overtly stigmatised and, aside from within the educational setting, when prescriptive usage is usually more of a focus than in everyday conversation, it often passes without comment (cf. Muysken Reference Muysken2000: 41; Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald, Aikhenvald and Dixon2006: 40).

The motivation for PAT-borrowing has been described as “an individual speaker’s scan for an optimal construction through which to communicate local meanings” (Matras Reference Matras2009: 243) or even “bilingual speech appearing in the disguise of monolingual speech” (Bolonyai Reference Bolonyai1998: 23). Further, it supports Muysken’s view (Reference Muysken2000: 252) that there is no “on-off” syntagmatic relation between the languages a speaker speaks but, rather, a co-existence between them. In French, this concept may be illustrated by the existence of compounds such as auto-école (‘driving school’), mini-jupe (‘mini skirt’), ciné-club (‘cinema club’), and grève attitude (‘strike attitude’) (cf. Loock Reference Loock2013), where lexical material from French is cast in the morphosyntactic frame of English (in these examples, the English pattern of right-headedness is substituted for the French pattern of left-headedness). Arguably, therefore, the English term that motivated the French term is not replaced but, as Muysken puts it, is “merely altered in its outer shape” (Reference Muysken2000: 266), with contact thus having the effect of “pairing the lexical shape of one language with the syntax of another” (Reference Muyskenibid: 266). Indeed, the gradual replacement in French of left-headed club de tennis by right-headed tennis club would presumably not have occurred had it not been for the existence of the term tennis club in English and, as seen with the example of ciné-club above, this syntactic pattern is now commonly used in French with the names of clubs. In such contexts, therefore, even though a bilingual speaker may be speaking one language, they are nevertheless able to draw on the grammars of both their languages, which are accessed simultaneously rather than sequentially. Processing two grammars with a single system can thus lead to similar linguistic organisational patterns being used for both languages (cf. Aikhenvald Reference Aikhenvald, Aikhenvald and Dixon2006: 45). As Matras (Reference Matras, Boeder, Schroeder, Wagner and Wildgen1998: 90) puts it, “languages in contact stimulate one another to generalise iconic structures, thereby promoting structural compatibility among them”, with the ultimate criterion of equivalence being, according to Johanson, “the speaker’s subjective assessment of what he or she feels to be close enough” (Reference Johanson, Jones and Esch2002: 294). Ostensibly, the speaker is therefore still maintaining the situational constraints on their choice of language (Matras and Sakel Reference Matras and Sakel2007: 832), with their languages separated in terms of lexical material but, in practice, the PAT “skeleton” (Muysken Reference Muysken2000: 278) of one language being, in some part, taken from a different language.

Johanson considers contact-induced language change within his code-copying framework, casting the MAT-/PAT- dichotomy as a distinction between global copies (i.e. MAT-borrowing), where “a unit of the model code is copied as a whole, including its form and functions” (Reference Johanson, Jones and Esch2002: 291),Footnote 7 and “selective” copying (i.e. PAT-borrowing), which involves “only selected structural – material [i.e. phonic properties], semantic [the denotative and connotative content], combinatorial [the internal constituency or external combinability] or frequential [frequency pattern] – properties of foreign blocks” (Reference Johanson, Jones and Eschibid: 292, insertions mine).

Matras and Sakel discuss the way in which what they term “pivot matching” (see §3.1 and elsewhere for examples) might provide a possible mechanism for some instances of PAT-borrowing. It is claimed that speakers identify a structure in the model language that plays a pivotal role in a particular construction and match it with a structure in the replica language, to which they assign a “pivotal role” in the replica construction (Reference Matras and Sakel2007: 829) in a way that respects the grammatical constraints of the replica language. In other words, the process of syncretisation between the languages in contact “will selectively target a point of reference which is perceived as ‘carrying’ the construction” (Reference Matras and Sakelibid: 836). They further suggest that the concept of pivot matching could explain why PAT-borrowing does not always involve a wholescale matching of constructions between the two languages involved in a given contact situation – and why the outcomes often result from a change in the distribution of an established organisational pattern.

2. Methodology

As discussed in §1, the present study represents the second part of an extensive examination of the different outcomes of language contact in Guernésiais. The data are therefore mainly drawn from the corpus presented in Jones (Reference Jones2024) although, for the sake of completeness, in certain cases they are supplemented with data drawn from Jones (Reference Jones, Jones and Esch2002) and (Reference Jones2015), corpora with a very similar age- and socioeconomic make up, which are here analysed within the framework of the current study. Accordingly, for the most part, the methodology followed in this study is identical to that set out in Jones (Reference Jones2024), with the data being collected from interviews with 46 native speakers of Guernésiais, most of whom – in keeping with the overall demographics of this particular speech community – had close connections to agriculture and farming. All speakers were fluent in Guernésiais although it was not necessarily still their main everyday language. For logistical and ethical reasons, the data presented were collected before the Covid-19 pandemic.Footnote 8 Given the advanced degree of language contact in the speech community (all speakers of Guernésiais are also fluent in English: no monolinguals remain) and the cessation of intergenerational transmission (Jones Reference Jones2015: §4.2), with most speakers aged over 65 at the time the data were collected, it has not been possible to consider usage related to proficiency in English, intensity of contact, age or social stratification.Footnote 9 All interviews were conducted by myself and in Guernésiais and took the form of free conversation. In an attempt to obtain naturalistic data and to lessen the effect of the observer’s paradox (Labov Reference Labov1972: 32), I was accompanied at all times by a fluent speaker of Guernésiais who was well known to the people being interviewed and who often took the lead in the conversation, a strategy which has, in other contexts, proved an effective way of enhancing the elicitation of casual speech, especially in cases where the researcher is not a native speaker of the variety under investigation (Turpin Reference Turpin1998: 223; Milroy and Gordon Reference Milroy and Gordon2003: 75; Bowern Reference Bowern and Hickey2010: 351). Involving a research assistant also made it possible to use social networks to locate speakers (cf. Milroy Reference Milroy1987), a strategy whose effectiveness has been demonstrated in other studies made of Norman (see, for example, Jones Reference Jones2001, Reference Jones2015).

Since PAT-borrowing does not involve the incorporation of tokens drawn from other-language material but rather, a “grafting” of the outer “shape” of one language onto the syntax of another, often involving no more than a difference in distribution of an existing organisational pattern, it is not only more difficult to identify than MAT-borrowing but also more difficult to “prove” and to discuss in a quantitatively meaningful way (cf. Heine and Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 261). Moreover, unlike with the MAT-borrowings discussed in Jones (Reference Jones2024), the different types of PAT-data cannot be as usefully compared in terms of their overall frequency, given the impossibility of establishing meaningfully at which precise point a particular minority distribution pattern, for example, has become a majority one for all members of a given speech community, precisely because it is difficult to determine exactly when two patterns come to mean the same thing for each individual speaker (cf. Heine and Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 75). Thus, in an attempt to confirm that a particular organisational pattern in Guernésiais represents a PAT-borrowing, usage is compared, where possible, to a corresponding construction in Mainland Norman, which is not in contact with English, and also to the data for Guernsey recorded in the Atlas Linguistique et Ethnographique Normand (Brasseur Reference Brasseur1980, Reference Brasseur1984, Reference Brasseur and Simoni1995, Reference Brasseur1997, Reference Brasseur2010, Reference Brasseur2019, hereafter ALEN).Footnote 10 For the sake of completeness, the number of instances in the corpus is also calculated when it is possible to do so meaningfully.

In order to make the Guernésiais data accessible to readers more familiar with French than with Norman, the utterances cited from the data are given an orthographic rendering based on the (largely French-based) spelling system used in the Dictiounnaire Angllais-Guernésiais (De Garis Reference De Garis1982, hereafter DAG: the only contemporary dictionary of Guernésiais). The linguistic feature being discussed is highlighted in bold.

3. Results

Since this study complements and completes Jones (Reference Jones2024), as in that study, the results are presented here by part of speech.

3.1 Verbs

Muysken (Reference Muysken2000: Chapter 7) describes verb compounds that combine elements from two languages as “bilingual verbs”. Such a description could arguably be extended to the verbs of Guernésiais that combine Guernésiais lexical material with an English underlying structure. This section illustrates some of the different types of PAT-borrowing found in the corpus in the context of the verbal system.

3.1.1 Prepositional verbs

Prepositional verbs are idiomatic expressions that combine a verb and a preposition to create a new verb with a distinct meaning: for example, from the English verb cut we have cut off (‘to stop the provision of something/to isolate something’) and cut down (‘to reduce something in size/to fell a tree’). Calqued English prepositional verbs are common in the corpus (186 tokens), even when indigenous equivalents exist. See, for example, (5)–(14), where the indigenous word is given in brackets. Sometimes (as in (6)), the calqued preposition accompanies a MAT-borrowing. As seen in (8) and (9), calqued prepositional verbs are so common in Guernésiais that some are even listed in the DAG (and are marked here as (L)) (cf. Jones Reference Jones2015: 153). Heine and Kuteva (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 53) describe preposition calquing as a frequent feature of languages in contact.

-

(5) Il fut copaï bas ‘It was cut down’ (abattre).

-

(6) Il a slidaï à bas ‘He slid down’ (drissaïr).Footnote 11

-

(7) J’ mettrai l’ naom bas ‘I’ll put the name down’ (enrégistraïr/écrire).

-

(8) Pour ne la lâtcher pas hors (L) ‘In order not to let her out’ (lâtcher).

-

(9) All’a pitché hors la djougue (L) ‘She threw out the jug’ (peltaïr).

-

(10) Ch’tait chéna qui mit aen p’tit mes éfànts hors ‘That’s what put my children out a bit’ (gueurvaïr).

-

(11) Nou dounnit à haut les tomates ‘We gave up [growing] tomatoes’ (r’nonchier/abàndounnaïr).

-

(12) Nou-s a dounnai à haut l’sécrétaire dé l’Assembllaïe ‘We gave up [being] the Assembllaïe secretary’(r’nonchier /abàndounnaïr).

-

(13) I baillit à haut, i retireit ‘He gave up, he retired’(r’nonchier/abàndounnaïr).

-

(14) L’Condor nous lesse avaout ‘The Condor [ferry] lets us down’ (bâtcher).

In utterances such as these, the “pivot” is the abstract meaning that can be assigned to the English preposition that forms part of these verbs, which is then matched with the preposition’s concrete meaning in Guernésiais (cf. Matras and Sakel Reference Matras and Sakel2007: 852). For Johanson, the verbs in (5)–(14) would be examples of combinatorial copying, with the combinatorial properties of English – here, the fact that these particular verbs may be combined with these particular prepositions – being copied onto units of Guernésiais. Such isogrammatism does not occur in Mainland Norman, where there is no contact with English and hence the corresponding verbs are never accompanied by these prepositions (cf. Trésor de la Langue Normande 2013).

3.1.2 Pronominal reflexive verbs

Certain Guernésiais verbs can have both reflexive and non-reflexive forms (Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson2008: 105). L’vaïr, for example, means ‘to raise (something)’ in its non-reflexive form but ‘to get up’ in its reflexive form (s’l’vaïr). When not being used reflexively, l’vaïr can only be transitive: in other words, *il lève (with the meaning ‘he gets up’) is an impossible structure. In this context, the clitic pronoun therefore forms part of the lexical specification of the verb. Like French, the conjugation of Guernésiais reflexive verbs requires a different reflexive pronoun for different persons of the verb (De Garis Reference De Garis1983: 343). The infinitive takes the 3sg/3pl reflexive pronoun sé in its base form (or in its citation form) but, as seen in (15), the person of the verb and the reflexive pronoun are co-referential. In other words, the pronoun varies if the infinitive refers to a non 3sg/3pl person of the verb.

-

(15) Ch’n’tait pas aisi d’m’l’vaïr de bouanne haeure ‘It wasn’t easy for me to get up early’ (1sg reflexive pronoun).

Although, in most cases, the traditional reflexive pronoun is used with pronominal verbs, as in (15) (368 tokens), the corpus contains 112 instances where the reflexive pronoun is omitted (illustrated in (16)–(22)). These are presumably PAT-borrowings from English, with the “pivot” in this case being the lack of a reflexive pronoun in the corresponding verbs of English, which is leading to the absence of such a pronoun in Guernésiais. In Mainland Norman, these verbs are always accompanied by a reflexive pronoun when used with the meanings in (16)–(22) (cf. Jones Reference Jones, Wolfe and Maiden2020: 300–302; see also ALEN maps 1184, 1185; Brasseur Reference Brasseur and Simoni1995: map 14; Collas Reference Collas1931: Q CCXVIII).

-

(16) Si vous avaïz l’vaï à quatre haeures ‘If you had got up at four o’ clock.’

-

(17) Il’ tait l’vaï à six haeures ‘He got up at six o’ clock.’Footnote 12

-

(18) Nou soulait l’vaïr à huit haeures ‘We used to get up at eight o’clock.’

-

(19) L’baté arrête à Jèrri ‘The boat stops in Jersey.’

-

(20) Il appeule “open market” ‘It’s called “open market”.’

-

(21) Des “pinche-tchu” qu’il’ app’laient ‘ “Pinch bottoms” as they are called.’

-

(22) Entertchié qu’il’ ont lavaï laeux moïns ‘Until they have washed their hands.’

Interestingly, this pivot also seems to motivate a second outcome, namely that finite reflexive verbs conjugated in the second person plural systematically feature the reflexive pronoun of the base form of the infinitive (sé) rather than the traditional (co-referential) 2pl reflexive pronoun (vous) (23)–(27) (cf. De Garis Reference De Garis1983: 343).Footnote 13 The fact that this replacement of the co-referential pronoun is documented by Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson2008: 40) suggests that such usage is relatively well established. Here therefore, the fact that the English verb does not change from the infinitive form when it is conjugated is leading, in Guernésiais, to PAT-borrowing of the English structure, with the sé reflexive pronoun seemingly reanalysed as part of an “invariable” infinitive. The use of sé as the reflexive pronoun of 2pl verbs is not documented for any other variety of Channel Island Norman, nor for Mainland Norman, although Heine and Kuteva (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 52) point to a similar change in the speech of some German speakers in Trieste who, under the influence of Slovenian, extend the 3pl reflexive pronoun to 1pl and 2pl referents.

-

(23) Quaï langue vous s’en allaïz d’visaïr? ‘Which language are you going to speak?’

-

(24) Vous s’n allaïz pas gognier ‘You are not going to win.’

-

(25) Eiouque vous s’n allaïz auch’t’haeure? ‘Where are you going now?’

-

(26) Vous s’entrecomprenaïz pas ‘You don’t understand one another.’

-

(27) À moins que vous ne s’levaïz ‘Unless you get up.’

It is also worth mentioning another possible motivating factor here, namely that, unlike in Jersey and Sark, the 1pl pronoun jé is virtually obsolete in Guernésiais (Jones Reference Jones2015: 136), where the impersonal pronoun nou(s) (= French on) is used instead, and almost categorically, to convey a 1pl meaning (Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson1981: 93, Reference Tomlinson2008: 39; De Garis Reference De Garis1983: 322ff). In other words, in contemporary Guernésiais the traditional 1pl form (28) is usually rendered as in (29).

-

(28) J’nous lavîmes ‘We washed ourselves.’

-

(29) Nou s’lavit ‘One washed themselves.’

Since the reflexive impersonal pronoun of Guernésiais (sé) is shared with the third person plural, the extension of its use to the 2pl pronoun could also be interpreted as internal simplification of the system of reflexive pronouns by way of levelling. Such levelling might be reinforced by the fact that the pronouns of the three persons plural show no variation in English. Indeed, as illustrated in utterances such as (30), the reanalysis of the Guernésiais plural structure as “subject pronoun + invariable verb stem prefix (sé) + verb”Footnote 14 could well account for the doubling of the reflexive pronoun that sometimes occurs (4 tokens).

-

(30) J’nous s’assiévimes ‘We sat down.’

To summarise, the lack of a reflexive pronoun in English in many verbs that would traditionally include one in Guernésiais seems to produce different types of PAT-borrowing in Guernésiais. One of these outcomes is the elimination of the reflexive pronoun of the Guernésiais construction while another results in the reflexive pronoun of the base form of the Guernésiais infinitive becoming invariable for the persons plural of the paradigm. From these results, it may be seen that PAT-borrowing does not always merely produce a copy of the model code in the replica code: it can also create new patterns of usage in the replica code from material available in that code.

3.1.3 Word order

In English, the verb to be may occupy the final position in an emphatic utterance such as yes, they are. In traditional Guernésiais, the corresponding verb, ête, tends not to occur in final position. However, as illustrated in (31)–(33), in the corpus, emphatic phrases with forms of ête in final position are relatively common (42 tokens), with the English structure underlying the Guernésiais lexical material. The pivot in this case is the fact that, although Guernésiais and English both have a verb ‘to be’, its distribution in both languages is different. Guernésiais therefore seems to be becoming influenced by the distribution of to be in the English model code, a further example of what Johanson defines as combinatorial copying (Reference Johanson, Jones and Esch2002: 292). Such usage is not found in Mainland Norman (cf. Université Populaire Normande du Coutançais 1995).

-

(31) Oui, mes daeux gràn’pères étaient! ‘Yes, my two grandfathers were!’

-

(32) Ah, oui, ch’tait ‘Ah yes, it was.’

-

(33) Oui, ma fomille était ‘Yes, my family was.’

3.1.4 3pl Verb conjugations

The corpus contains several instances of 3pl verbs being used in Guernésiais in place of 1pl verbs (10 tokens) (34)–(35). Here, the invariability of the persons plural of the English verb paradigm seems a likely pivot, leading to combinatorial copying involving the redistribution of the 3pl verb form. Again, no evidence of such usage is found in Mainland Norman.Footnote 15

-

(34) Ch’est bouan pour naons qui pâlent l’Guernésiais ‘It’s good for us who speak Guernésiais.’

-

(35) Ma soeur et mé s’en furent ‘My sister and I went.’

3.1.5. Semantic copying

Formal similarity between a word of English and a word of Guernésiais can sometimes lead to semantic copying, whereby what Johanson (Reference Johanson, Jones and Esch2002: 292) terms the “denotative or connotative content elements of model code [English] units” (my insertion) are copied onto Guernésiais words. This type of PAT-borrowing, also documented by Weinreich (Reference Weinreich1963: 48), is termed “loan shift” by Appel and Muysken (Reference Appel and Muysken1993: 165) and is considered by Thomason and Kaufman (Reference Thomason and Kaufman1988: 76, 90) as an indication that speakers of the recipient languages are under reasonably intense cultural pressure from another speech community.

The corpus contained many examples of loan shifts (107 tokens) (cf. (36)–(40)). In these cases, the pivot is created by the fact that the English verb can have two meanings: often one concrete or literal and the other abstract. The polysemous meaning of the English verb becomes grafted onto the Guernésiais verb so that it too becomes polysemous. For example, in (36) and (37) the verb run/courre has the meaning of ‘to proceed rapidly on foot’ in both English and Guernésiais. However, in traditional Guernésiais, courre does not share the extended meaning of the English verb run, namely ‘to organise/make happen, function’ (36) or ‘to travel’ (37), extended meanings which become copied onto Guernésiais (cf. les bosses tcheurent ‘the buses run’, DAG p. 155). In (38), the Guernésiais verb saver means ‘to know’ in the sense of ‘to know a fact’ but, on the model of English, its meaning has been extended in Guernésiais to encompass ‘to be familiar with a person, place or thing’ and, similarly, in (39), the meaning of passaïr ‘to pass’ [movement or time] has been extended in Guernésiais to ‘to succeed in an exam’ (cf. DAG p. 127). In (40), the English meaning ‘to show one’s allegiance to’ has been copied onto supportaïr, which traditionally only meant ‘to support, to endure’ (cf. DAG p. 283). These utterances would not be understood by a speaker of Mainland Norman.

-

(36) Ch’est iaeux qui courrent l’île ‘It is they who run the island.’

-

(37) Quànd les bosses c’menchaient à courre ‘When the buses started to run.’

-

(38) J’n’ savais pas grànd’ment les mouissaons ‘I didn’t know much about birds.’

-

(39) Mon p’tit fils pâssit s’n exâmàn à l’university ‘My grandson passed his exam at university.’

-

(40) J’ai terjous supportaï lé team dé Wales ‘I have always supported the Welsh team.’

Although no examples were found in the corpus, an instance of loan shift has also been recorded with the verb travailler, where the meaning of the Guernésiais verb ‘to work’ (in the sense of employment, labour) is extended to encompass the English meaning of ‘to function’ – sht ologe travail pas ‘that clock doesn’t work’ (Sallabank Reference Sallabank2013: 127) [her spelling].

3.1.6 The subjunctive

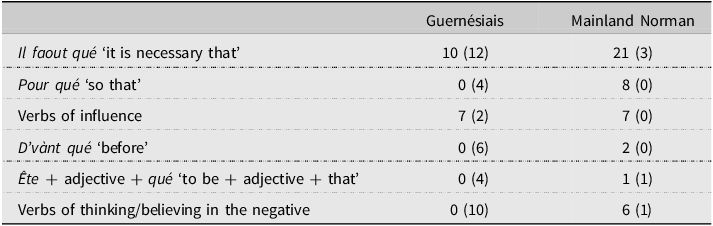

No consensus exists between the metalinguistic sources on Guernésiais as to the use of the subjunctive, which is more restricted than in French (see Jones Reference Jones2000; cf. Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson1981: 91). As indicated in Table 1, which compares usage in a corpus of Guernésiais and Mainland Norman (Jones Reference Jones2015: 127–130), the subjunctive still forms part of contemporary Guernésiais (cf. (41)) but – as is further demonstrated in a large-scale study of the Guernésiais subjunctive (Jones Reference Jones2000) – it is also frequently replaced by the indicative (cf. (42)), holding ground in only two of the contexts examined, and even then not completely.

Table 1. Use of the subjunctive in Guernésiais and in Mainland Norman (tokens of the indicative are given in brackets)

-

(41) Arrête que j’maette chén’chin hors d’la vaeue ‘Wait while I put this out of your sight’ (1sg present subjunctive).

-

(42) Faout qu’j’lé lliés ‘I have to read it’ (1sg present indicative).

The combinatorial properties of the English structures are clearly being copied onto Guernésiais and this is resulting in increasingly distinct usage from Mainland Norman, where the subjunctive predominates in the same contexts (cf. Jones Reference Jones2015: 128).

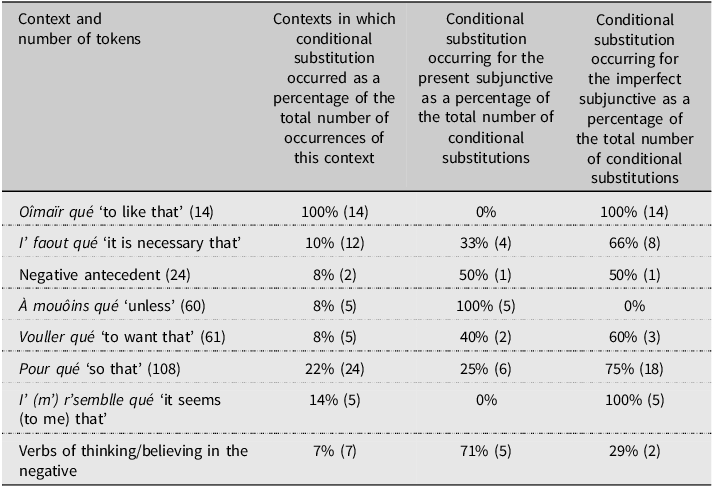

Table 2, from Jones (Reference Jones2000), illustrates that, in Guernésiais, the conditional may be substituted for both the present subjunctive (cf. (43)) and the imperfect subjunctive (cf. (44)). As will be discussed, this may also be explained in terms of pivot matching.

Table 2. Contexts in which the conditional is substituted for the subjunctive in Guernésiais speech (number of tokens in brackets)

The subjunctive has all but been eliminated from spoken English and this seems likely to be playing a part in its reduced usage in contemporary Guernésiais (cf. among others, Heine and Kuteva (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 20), who state that “categories for which there is no equivalent in the model language are in danger of being lost”). Yet, if the pivot in Guernésiais is the finite expression of an action combined with the expression of a modality, the replacement of the eliminated subjunctive form by conditional substitution in these contexts (cf. (43) and (44)) may indicate that Guernésiais is in fact replicating this pivot via a different formula – namely by copying the mood of the model language whilst preserving modality-marking.

-

(43) I’ faout qu’ tu verrais tout chena ‘You must see all that.’

-

(44) A voulait qu’j’arrêtrais mon travas ‘She wanted me to finish my work.’

The fact that conditional substitution is also found in français populaire and some regional varieties of French (cf. Gadet Reference Gadet1992: 89; Brunot and Bruneau Reference Brunot and Bruneau1969: 320; Cohen Reference Cohen1965: 3; Grevisse Reference Grevisse1988: §869) suggests that, in this context, some form of broader internal simplification may be reinforcing any PAT-borrowing that may be present in Guernésiais. Nevertheless, in Guernésiais, conditional substitution occurs in a greater number of contexts than in French and it is also found in contexts where it would not usually occur in French, such as after verbs of volition (such as vouller qué ‘to want that’) and phrases that express purpose (such as pour qué ‘so that’). Pivot matching therefore also provides one possible interpretation of these results.

3.1.7 Future tense expression

Like French, Guernésiais has two verbal paradigms to express future action: a synthetic form (45) (Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson2008: 81) and a de-allative periphrastic form (46). The latter is traditionally used to express an action taking place in the near future and, like the future tense of English, it is formed from the present tense of ‘to go’ and the infinitive (Reference Tomlinsonibid: 84).

-

(45) J’vendrai la maisaon ‘I will sell the house.’

-

(46) J’m’en vais vendre la maisaon ‘I’m going to sell the house.’

349 examples of future tense usage were recorded in the corpus. 94 of these were synthetic forms and 255 were periphrastic forms. Given that both types of forms are used in a grammatically correct way, it is difficult to determine quantitatively the extent of any PAT-borrowing. However, since nearly three out of four future tense forms produced by speakers were de-allative, the data do suggest that PAT-borrowing from English may be causing an increase in frequency of this form, to the detriment of the synthetic future tense.Footnote 16 In this case, therefore, no obvious change in structural constituency has occurred, merely that a construction which already exists in Guernésiais is gaining ground and seems to be becoming less marked. Johanson describes this as frequential copying (Reference Johanson, Jones and Esch2002: 292). This development also conforms to the widespread increase in transparency observed in obsolescent languages whereby synthetic forms may be replaced by analytic structures (Jones Reference Jones1998: 251, cf. Schmidt Reference Schmidt1985: 61; Dimmendaal Reference Dimmendaal and Brenzinger1992: 119). Indeed Heine and Kuteva (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 106–107) describe a similar outcome in the system of future tenses used in Pennsylvanian German and in the Yiddish of the Los Angeles area. The present study agrees with Thomason (Reference Thomason, Amiridze, Arkadiev and Gardani2014: 43), contra authors such as Heine (Reference Heine, Siemund and Kintana2008), that, although it does not introduce an entirely new component into the language, a change in the frequency of a particular structure should still be considered as language change. Of course, it is not impossible to discount the fact that, as discussed above in the case of the pronominal reflexive verbs and the subjunctive (see, respectively, §§3.1.2 and 3.1.6), the change in use of the Guernésiais de-allative future tense form may also have an internal motivation, namely the simplification of a system with two “competing” future tense forms (cf. Kroch Reference Kroch1989).

3.2 Adjectives

Unmarked monosyllabic attributive adjectives and unmarked attributive adjectives of colour are traditionally pre-posed in Guernésiais. Other adjectives are traditionally post-posed (Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson1981: 47). However, recent studies have documented that, in the contemporary language, the pre-nominal position is becoming unmarked for all adjectives (cf. (47)–(49)), a development which does not occur in Mainland Norman (cf. Jones Reference Jones, Jones and Esch2002: 154–155, Reference Jones2015: 132–134).Footnote 17 These results were confirmed in the corpus, where 27 of the 80 tokens of the aforementioned adjective types are pre-posed. The change in word order in Guernésiais indicates the presence of PAT-borrowing in the form of both combinatorial and frequential copying with the pivot being that, in English, only one position (pre-nominal) is available for adjectives. Since the pre-nominal adjectival slot is already available in Guernésiais, albeit as a restricted pattern, the fact that it is increasingly becoming the unmarked position for all adjectives is likely to remain un-noticed by speakers since, rather than representing new usage, it is simply the extension of a minority-use pattern in the language to a majority-use pattern (cf. Heine and Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 41).

-

(47) Ch’est aen têtu cat ‘It’s a stubborn cat.’

-

(48) All’ a énne différente vie auch’t’haeure ‘She has a different life now.’

-

(49) Ouécqu’est la pllate terre ‘Where the flat ground is.’

Borrowed adjectives are also pre-posed (cf. (50)–(52)).

-

(50) Ch’est énne nice persaonne ‘He’s a nice person.’

-

(51) Des extras lifts ‘Extra lifts.’

-

(52) Ch’est des china coupes ‘They are china cups.’

An alternative explanation, of course, is that this change may be occurring via internal simplification, with the choice of two available adjective positions in contemporary Guernésiais being reduced to one.

3.3 Adverbs

Analysis of the adverbs in the corpus revealed the presence of different kinds of PAT-borrowing.

3.3.1 Semantic copying

Two forms were found of what Johanson defines as adverbial semantic copying (cf.§3.1.5 above). The first of these, illustrated in (53)–(55), takes the form of straightforward calquing, which gives these utterances meanings which would not be easily understood by a speaker of Mainland Norman.

-

(53) Pas terribllément ‘not terribly.’

-

(54) Ch’tait coum chena dans les dix neuf sésàntes ‘It was like that in the nineteen sixties.’

-

(55) J’tais à mon tout seu ‘I was on my own.’Footnote 18

The second type of adverbial semantic copying present in the data is the use of adjectives for adverbial functions (cf. (56)–(58) which illustrate each of the three types present in the corpus, with the tokens of différent (44 in number) being particularly common). Such usage is a well-documented feature of Guernsey English (Ramisch Reference Ramisch1989: 161) and therefore makes PAT-borrowing a likely motivation. Indeed, the corpus also contains several English adjective MAT-borrowings conveying an adverbial function (cf. (59)–(60)). This type of PAT-borrowing therefore introduces new usage into Guernésiais rather than affecting the distribution of an existing pattern of usage.

-

(56) I d’visent différent à chu q’nou d’vise ‘They speak differently to how we speak.’

-

(57) Si vous d’vizaïz aen p’tit pusse tràntchille ‘If you speak a little bit more slowly.’

-

(58) I’ pâle parfait ‘He speaks perfectly.’

-

(59) Ch’n’est pas tous qui écrivent si plain ‘It’s not everyone who writes so plainly.’

-

(60) I’va en Frànce direct Footnote 19 ‘He goes to France directly.’

3.3.2 Broadening of meaning

Like French, but unlike English, Guernésiais makes use of a marked variant of the affirmative adverb oui ‘yes’ to emphasise an affirmative response or to contradict a negative (DAG p. 281; Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson2008: 61). This form, /sie/ (often spelt si-est), is illustrated in (61).Footnote 20

-

(61) Tu n’vians pas? – Si-est ‘Aren’t you coming? – Yes, I am.’

Jones (Reference Jones, Jones and Esch2002: 156) notes how, in an analysis of 43 speakers producing utterances that contradicted a negative, only 32 speakers used the form si-est, with 11 speakers using instead the unmarked affirmative adverb oui. The lack of an equivalent “strong” affirmative in English seems to be the pivot contributing to the broadening of meaning of oui in Guernésiais, whose use is being extended to contexts that would traditionally require the marked variant. This is another example of frequential copying, with a majority-use pattern replacing a minority-use pattern. No such usage is recorded for Mainland Norman (cf. ALEN map 1493).

3.4 Prepositions

A similar broadening of meaning is apparent in the prepositional system of Guernésiais, specifically with regard to the prepositions that denote the different meanings of English ‘with’.Footnote 21 Dauve is the unmarked preposition (cf. (62)) but, to convey an instrumental meaning, the form used in traditional Guernésiais is atou (cf. (63)) and, for a comitative meaning, it is à quànté (cf. (64)). Like the affirmation structures described in §3.3.2, this therefore also represents a case where English lacks the oppositions that are present in Guernésiais.

-

(62) Counnis-tu chut haomme dauve l’s bllus iaers? ‘Do you know that man with blue eyes?’

-

(63) J’ai copaï l’pôin atou l’couté ‘I have cut the bread with the knife.’

-

(64) Va à quànté li ‘Go with him.’

Notwithstanding the descriptions in metalinguistic sources such as the DAG (p. 214) and Tomlinson (Reference Tomlinson2008:21), only one of these three prepositions, dauve, is present in the 64 tokens of ‘with’ prepositions analysed in Jones (Reference Jones2015) (38 unmarked, 10 instrumental, 16 comitative). Examples of the contemporary usage found are given in (65)–(67).

-

(65) Aen scabet dauve treis pids ‘A stool with three feet’ (unmarked).

-

(66) Nou veyait pas d’vielles gens par les càmps, i n’marchaient pas dauve des bâtaons ‘We didn’t see old people going round about, they didn’t walk with sticks’ (instrumental).Footnote 22

-

(67) Il allait dauve sa gràn’mère ‘He used to go with his grandmother’ (comitative).Footnote 23

Although the English word with has not been copied into Guernésiais in these examples (as a MAT-borrowing), the fact that English only has one preposition, rather than three, to denote the functions of ‘with’ has led to a reduction in the use of atou and à quànté in contemporary Guernésiais. In other words, one of the three ‘with’ patterns of traditional Guernésiais has increased in frequency to become the only pattern. Dauve is therefore undergoing progressive desemanticisation as the distinct semantic contents of atou and à quanté (and indeed, the forms themselves) are lost under the influence of English. This development is, of course, in line with the well-known tendency in obsolescent languages for speakers to overgeneralise unmarked categories to contexts that historically require marked variants (cf. Jones Reference Jones1998: 251–252).

The change in use of ‘with’ prepositions in contemporary Guernésiais represents another example of frequential copying in that the form being generalised is not created on the basis of English but is, rather, extending its usage on the basis of English. A similar tendency is described by Dorian (Reference Dorian1981: 136), who notes a marked reduction in the 11 pluralisation strategies of East Sutherland Gaelic via the generalisation of simple suffixation, the pluralisation device used in English – the language with which East Sutherland Gaelic is in contact.

Interestingly, and notwithstanding the descriptions contained in many metalinguistic works, including Dumeril and Dumeril (Reference Dumeril and Dumeril1849: 3), Decorde (Reference Decorde1852: 45), Robin et al (Reference Robin, Le Prévost, Passy and De Blosseville1879: 32–33), Romdahl (Reference Romdahl1881), De Fresnay (Reference De Fresnay1881: 29), Fleury (Reference Fleury1886: 73), Barbe (Reference Barbe1907: 10) and von Wartburg (Reference Von Wartburg1922– 1946 vol 2, II: 1417), Jones (Reference Jones2015: 139) found that a single preposition (d’aveu) is also becoming increasingly used to convey all the different meanings of ‘with’ in the Mainland Norman of the Cotentin peninsula (197 tokens [118 unmarked, 40 instrumental, 39 comitative]). This is presumably because Mainland Norman is displaying PAT-borrowing from French, which uses the sole form avec for all three of the ‘with’ functions described above.

3.5 Pronouns

3.5.1 Gender-marking

Like French but unlike English, Guernésiais marks masculine and feminine gender on its 3sg subject and object pronouns when these refer to inanimate referents, as such referents always carry gender (cf. (68) and (69), where the pronoun and its referent are given in bold).

-

(68) L’couté M est sus la table. Il M est aidgu ‘The knife is on the table. It is sharp’ (lit. ‘he’).

-

(69) La paomme F est dans l’ponier. All’ F est p’tite ‘The apple is in the basket. It is red’ (lit. ‘she’).

Traditional gender-marking is generally observed in the corpus, with 223 of the 230 tokens of referential pronouns respecting such usage. However, seven speakers each produced one token of a masculine pronoun when referring to a feminine referent. This non-traditional usage is illustrated in (70) and (71).Footnote 24

-

(70) L’aoute fomille F, i M continuit supareillement autour de l’eghise ‘The other family, it continued especially around the church’ (lit. ‘he’).

-

(71) Chaque paraesse F faisait coum i M voulait ‘Each parish did as it wanted’ (lit. ‘he’).

The (albeit slight) variation that exists in this context may be indicative of an incipient change which could be interpreted as PAT-borrowing from English. Since, in most cases, only one noun topic occurs in a given utterance, it is unlikely that any ambiguity will exist for the interlocutor in terms of the pronoun’s referent. Therefore, when the referent is inanimate, the low functional load that gender carries in such utterances allows for its effective “neutralisation” in these contexts without any resulting difficulties of comprehension. Whilst the phonetic form of the referential pronoun is therefore unmistakably Guernésiais, its use in utterances such as (70) and (71), where it keeps its referential function but seems to have lost its gender specification, is more aligned with English it, which thus represents the pivot.

3.5.2 Pronoun calquing

When the argument of a verb does not match in Guernésiais and in English, PAT-borrowing may take the form of pronoun calquing. Although relatively infrequent in the corpus (18 tokens), examples of non-traditional usage are found with five different verbs, each of which is illustrated in (72)–(76). No such usage is found in Mainland Norman (cf. Jones Reference Jones, Wolfe and Maiden2020: 298–300).

-

(72) I mànchtait Guernési ‘He missed Guernsey’, where the experiencer [in bold] has changed from indirect object to subject (1 token of non-traditional use in the corpus).

-

(73) Ch’est énne mappe qué mon haomme lé dounnit ‘It’s a map that my husband gave him’, where the recipient [in bold] has changed from indirect to direct object (1 token of non-traditional use in the corpus).

-

(74) J’lé répaonds en Guernésiais ‘I answer him in Guernésiais’, where the recipient [in bold] has changed from indirect to direct object (1 token of non-traditional use in the corpus).

-

(75) Nou s’en va les apprendre lé Guernésiais ‘We are going to teach them Guernésais’, where the recipient [in bold] has changed from indirect to direct object (3 tokens of non-traditional use in the corpus).

-

(76) J’les pâlais souvent ‘I spoke to them often’, where the recipient [in bold] has changed from indirect to direct object (12 tokens of non-traditional use in the corpus).

4. Conclusion

This study completes a detailed examination made of the linguistic outcomes of language contact in contemporary Guernésiais, a language currently in an advanced stage of shift. It is undertaken using the theoretical framework of MAT- and PAT-borrowing, devised by Matras and Sakel (see, for example Matras and Sakel Reference Matras and Sakel2007) and complements the findings of Jones (Reference Jones2024), which centres on the more easily-identifiable MAT-borrowing (lexical borrowing and code-switching). In contrast to Jones (Reference Jones2024), the present study has focused on language change where structural patterns are transferred but not the morphemes themselves (cf. Thomason Reference Thomason, Amiridze, Arkadiev and Gardani2014: 31). As has been stated, this type of language change is arguably more “invisible” to speakers since no easily identifiable “other language” material is present.

Evidence of PAT-borrowing from English is found in the Guernésiais of all the speakers interviewed and also in all the parts of speech examined (verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and pronouns). This finding is consistent with the long history of intensive contact between Guernésiais and English and with the advanced degree of bilingualism that exists within the Guernésiais speech community (cf. Thomason Reference Thomason, Amiridze, Arkadiev and Gardani2014: 42; Heine and Kuteva Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 13). The analysis in this study has illustrated instances of where i) a category of Guernésiais has been restructured to align more with a corresponding category in English (see, for example §§3.1.2 [pronominal reflexive verbs], 3.2 [adjective position], 3.3.2. [affirmation strategies], 3.4 [‘with’ prepositions] and 3.5.1 [gender-marking in pronouns]); ii) a new pattern of usage has been assigned to an existing category, thereby extending its range (see, for example §§3.1.3 [word order], 3.1.4 [3pl verb conjugations], 3.1.7 [future tense expression], 3.2 [adjective position], 3.3.2. [affirmation strategies], 3.4 [‘with’ prepositions], 3.5.1 [gender-marking in pronouns] and 3.5.2 [pronoun calquing]); and iii) a new category replaces an existing one (see, for example §§3.1.1 [prepositional verbs], 3.1.3 [word order] and 3.1.6 [subjunctive]). In some cases, the “new” and “old” structures may co-exist side-by-side (see, for example, §§3.1.4 [3pl verb conjugations], 3.1.6 [subjunctive], 3.1.7 [future tense expression], 3.5.1 [gender-marking in pronouns] and 3.5.2 [pronoun calquing]).

Unless its history is well documented, it may be impossible to pinpoint the origin of a PAT-borrowing (cf. Csato Reference Csató, Jones and Esch2002: 326), which is likely to start life as a momentary (nonce) innovation on the part of a bilingual speaker. Since no difficulties of comprehension arise, such usage may remain uncommented upon by an interlocutor and, if replicated by a significant enough proportion of the speech community, it may become incorporated as a long-term change, with its ultimate adoption depending on its acceptability to the speaker (Matras and Sakel Reference Matras and Sakel2007: 852). It is important to underline, however, that Guernésiais is not being completely restructured in that, although change may be seen in a number of its patterns of usage, it has not adopted a wholly English morphosyntax.

Johanson discusses how copies may become conventionalised in the usage of individuals and/or speech communities, with new patterns becoming normal (Reference Johanson, Jones and Esch2002: 298) as what started life as non-conventionalised phenomena become accepted, leading to the establishment of new sets of norms. As Romaine puts it, “although the semantic differences in the bilinguals’ system are originally attributable to contact, they now provide the basis for an emergent set of norms” (Reference Romaine1989: 163). It would seem that there might potentially be most scope for such a development in a fully bilingual speech community such as that of Guernésiais, where the linguistic norms remain to some extent uncodified and where, as yet, no formal mechanism exists for any norms that might be established to be transmitted within the community.Footnote 25 In such cases, “however startling or reprehensible they may appear to unilinguals or individuals only familiar with the unilingual norm, interference-induced innovations […] in time may come to constitute instances of new community norms” (Mougeon and Beniak Reference Mougeon and Beniak1991: 220; cf. Haugen Reference Haugen and Hornby1977; Jones Reference Jones2005b).

As discussed, therefore, some PAT-borrowings will probably become new norms – for example, certain calqued prepositional verbs, such as those cited in §3.1.1 some of which are already listed in the DAG, the generalisation of sé as the invariable plural reflexive pronoun, now recorded in Tomlinson’s grammar (Reference Tomlinson2008: 40) (cf. §3.1.2), certain loan shifts (cf. §3.1.5 for an example which is now listed in the DAG) and the pre-nominal position of adjectives (cf. §3.2, Tomlinson Reference Tomlinson2008: 23). However, others may remain more idiolectal – see, for example, the use of 3pl verbs in traditional 1pl contexts (cf. §3.1.4), the broadening in meaning of the affirmative adverb (cf. §3.3.2) and gender-marking in 3sg referential pronouns (cf. §3.5.1). Idiolectal PAT-borrowing, in the form of underlying English organisational patterns in Guernésiais, do not of course pose any difficulties to comprehension since the fully bilingual nature of the Guernésiais speech community means that any structure that may emerge as dominant already forms part of its (English) linguistic repertoire. As Matras (Reference Matras, Amiridze, Arkadiev and Gardani2014: 54) comments, “In structural and functional terms, pattern replication facilitates the generalisation of constructions across the repertoire while maintaining the overt separation of form.”Footnote 26 In other words, speakers will still understand the PAT-borrowed components of Guernésiais as Guernésiais since any morphosyntactic differences from the traditional language that may occur will still map onto a morphosyntax that they know well. Although therefore Guernésiais and English are kept separate functionally, in practice the speech community seems open to, or is at least uncritical of, some degree of overlap between these languages in terms of shared combinatorial structures and frequential patterns.Footnote 27 Indeed, the absence of comments on the presence of PAT-borrowings suggests that speakers may not even notice that it is occurring. In such a context, it is easy to see how idiolectal usage in the form of “nonce” PAT-borrowings from English (or, to use Heine and Kuteva’s term, “spontaneous replication” (Reference Heine and Kuteva2005: 116)) may come to be used in Guernésiais as unproblematically as nonce MAT-borrowings (cf. Jones Reference Jones2024) and how such forms have the potential to propagate within the speech community (cf. Matras and Sakel Reference Matras and Sakel2007: 851). As Aikhenvald writes, “Innovations have a better chance in a situation where there is little, or no, resistance to them” (Reference Aikhenvald, Aikhenvald and Dixon2006: 41). As discussed in §1.2, it is interesting to consider whether, in a context of language shift, PAT-borrowings may represent a way of enabling speakers to continue speaking within the language choice parameter set for the conversation even when the sociolinguistic setting may have led to a different language holding sway in their internal grammar.

This study has also highlighted a major difference between MAT- and PAT-borrowing, namely that, whereas MAT-borrowing can only be explained with reference to the dominant language (cf. Jones Reference Jones2024), some apparent instances of PAT-borrowing can also on occasion admit an internal explanation, such as simplification, without any clear means of determining which motivation predominates (see, for example, §3.1.2 [pronominal reflexive verbs], §3.1.6 [subjunctive], §3.1.7 [future tense expression], §3.2 [adjective position], §3.4 [‘with’ prepositions]; cf. also Jones Reference Jones2005b:168–170). It is therefore interesting to consider whether some of the changes discussed herein might have occurred in Guernésiais even if it had not been in contact with English (cf. Burridge Reference Burridge, Aikhenvald and Dixon2006:188) and whether, in contexts such as this, language contact and what we might term the general tendencies of language change may, in fact, be serving to reinforce one another.

Competing interests

The author declares none.