Many people in Caucasus, Central Asia, East Africa, Latin America, or Western Balkans – to name a few – resolve their disputes through religious or customary justice (Haas and Khadka, Reference Haas and Khadka2019; Lazarev, Reference Lazarev2019; Trejo, Reference Trejo2012). In some cases, informal justice is limited to domains that are not regulated by the state law (e.g. punishment for breaking an engagement). Other times, however, informal justice encroaches on the competences of the state law, for example, by adjudicating murder cases. The co-existence of formal and informal laws makes citizens uncertain whether and when a formal or informal justice applies, rendering both legal orders dysfunctional (Eck, Reference Eck2014). Along with its positive effects on conflict resolution (Hartman, Blair and Blattman, Reference Hartman, Blair and Blattman2021), informal dispute settlement may also lead to the proliferation of violent and radical behaviors (Garcia-Ponce, Young and Zeitzoff Reference Garcia-Ponce, Young and Zeitzoff2022; Jung and Cohen Reference Jung and Cohen2020, for an exception, see: Magaloni, Gosztonyi and Thompson Reference Magaloni, Gosztonyi and Thompson2022). What explains the prevalence of informal justice?

Three influential explanations propose that people rely on informal justice: (i) when they lack resources to access state justice; (ii) when they believe that state justice is inefficient; and (iii) when state justice is at odds with local customs regulating dispute resolution. Conceptually, the three accounts are distinct, focusing on micro-, macro-, and meso-level dynamics. The explanations link the choice of informal justice, respectively, to individual opportunities, quality of institutions, or collective action dynamics. They thus have different policy implications for strengthening the rule of law (Blair, Karim and Morse, Reference Blair, Karim and Morse2019). Empirically, however, it is difficult to parse these accounts apart. Perhaps, local customs that prescribe informal justice are common in impoverished communities with inefficient state institutions (see Baldwin, Reference Baldwin2016).

To address this identification problem, we design a novel preregistered test based on assessments of hypothetical vignettes that describe fictitious characters who are involved in common legal disputes. Some disputes regard civil law cases in which informal justice could be a desirable complement to state justice (see Van der Windt et al., Reference Van der Windt, Humphreys, Medina, Timmons and Voors2019). Other disputes, however, present criminal law cases in which informal justice obstructs and clashes with the default state legal system. Throughout the vignettes, we randomly manipulate vignette characters’ resources, their beliefs about the efficiency of state justice as well as information about local customs regulating dispute settlement in the characters’ communities. We present our vignettes to a random sample of citizens of Kosovo, a country where informal dispute settlement is common (Trnavci, Reference Trnavci2010). Our survey respondents assess how likely it is that a given vignette character chooses to resolve their dispute through state or non-state (religious or customary) justice, given the described circumstances. The respondents then report their own preferences for a given justice forum in similar situations.

We find that respondents associate informal justice with vignette characters who believe that state justice is inefficient and at odds with local customs of dispute settlement. These assessments cannot be explained by the type of a studied dispute; hence, the complementarity or substitutability of formal and informal justice. We detect similar patterns while studying the correlates of survey respondents’ own normative justice preferences. Focusing on behaviors, our additional (not preregistered) tests show that the average mistrust in formal justice and the share of population who prefers informal justice in a municipality correlate with higher numbers of actual informal dispute settlement cases there, as reported in news media. Lastly, we provide suggestive evidence that our findings generalize to other (dissimilar) contexts – both in terms of justice preferences and actual behaviors.

Determinants of informal justice

The literature on legal pluralism and extra-legal governance points to three main explanations of informal justice, which operate at the micro-, macro-, and meso-levels.

Resourcelessness. Some scholars argue that preference for informal justice could be motivated by accessibility concerns, related to the lack of personal resources to access formal justice (Arsovska and Verduyn, Reference Arsovska and Verduyn2008; Haas and Khadka, Reference Haas and Khadka2019). This is an individual, micro-level explanation. Access to informal justice is less bureaucratized and thus more affordable than access to the state legal system. This is particularly important for individuals with limited resources, who, for example, cannot afford to hire a lawyer. Greater accessibility of informal justice need not be conceived in terms of material resources. Customary or religious justice could also be seen as more accessible insofar as it is less discriminatory towards certain groups (e.g. language minorities) and more “legible” for people who are not well trained in law (Tyler, Reference Tyler2003). Greater legibility, in turn, makes informal justice easier to navigate for less resourceful individuals.

Efficiency concerns. Another group of studies proposes that the preference for informal justice may be related to its greater efficiency compared to the efficiency of the state legal system (Gambetta, Reference Gambetta1996; Milhaupt and West, Reference Milhaupt and West2000). This is an institutional, macro-level explanation. Informal justice is less bureaucratic. As such, it takes less time to find a solution to a given dispute through informal justice. Informal adjudicators themselves – such as religious clergy or local elders – often have interest in reaching dispute settlement as soon as possible in order to appease conflicted sides and prevent further conflict in their communities. Moreover, settlements reached through informal justice are usually more promptly enforced due to close local-level monitoring (Giustozzi and Baczko, Reference Giustozzi and Baczko2014).

Local conventions. Finally, people may use informal justice because it represents a longstanding convention of how communities solve their disputes (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein1992; Hadfield and Weingast, Reference Hadfield and Weingast2014). This is a group, meso-level explanation. The source of informal justice conventions can be manifold. At times, these conventions originate from a clash between state laws and local community preferences, for example, when state justice focuses on retribution in a within-community conflict, while the community favors reconciliation (Ellickson, Reference Ellickson1991). In other contexts, informal justice simply safeguards traditional moral/ideological systems (Nussio, Reference Nussio2023).

Local conventions may also originate from the accessibility and efficiency concerns described above. However, the conventions explanation differs from the above accounts because it posits that communities continue to use informal justice irrespective of the original conditions that give rise to a particular legal convention. Some communities can thus be “trapped” in reliance on customary justice even if accessibility and efficiency of state justice are no longer a problem. For one, an individual may find it unfeasible to unilaterally deviate from local community norms. Collectively, a norm change poses a coordination problem, which is aggravated by the fact that individuals cannot observe others’ private justice preferences (see Andrighetto and Vriens, Reference Andrighetto and Vriens2022).

Design

We test the above explanations of informal justice in a preregistered experiment in Kosovo (preregistration link). Footnote 1 This Western Balkan country (map in Figure A1 in Online Appendix) marks a highly relevant case for our study because its citizens rely on an array of religious and customary forms of dispute resolution (details in Appendix A.1 in Online Appendix). These include community mediation according to the Kanun – a set of Albanian customary laws, orally transmitted since the 15th century and codified in the 19th century (Trnavci, Reference Trnavci2010) – and dispute settlement based on the Islamic law sought through local imams.

We conduct a representative survey of 2,405 Kosovo Albanians (see Appendix A.2 in Online Appendix). We measure respondents’ justice preferences and their beliefs about the use of informal justice by implementing a vignette experiment approved by institutional review boards at the Collegio Carlo Alberto and British Council (details in Appendix A.3 in Online Appendix). We expose our respondents to descriptions of fictitious characters involved in hypothetical but common civil and criminal disputes. We manipulate the vignette characters’ attributes regarding their accessibility to state justice and their beliefs about state justice efficiency and its compatibility with local customs. We ask respondents to assess whether the vignette characters plausibly resolved their dispute through formal or informal justice and how, in respondents’ opinion, similar disputes should be resolved more generally. Below, we provide an example of our vignette:

Faik and his sister Shqipe both claimed to have the right to the same plot of land which belonged to their deceased parents. Faik wanted to keep the entire plot of land, while Shqipe was asking for her share. At the time when Shqipe was trying to resolve the issue, she was (H1) [poor/wealthy]. She also thought that the state courts would solve the problem (H2) [very slowly/very quickly]. And we also know that Shqipe believed that (H3) [nobody around her/everybody around her] would resolve such issues through the state.

Now, knowing this about Shqipe, how do you think she tried to resolve this problem? [Answer choices: (i) state authority, (ii) a religious cleric, or (iii) community mediation according to the Kanun]

How do you think people should resolve this issue? [Answer choices as above] Footnote 2

Respondents can indicate only one justice forum. While we can envision a situation in which someone is willing to try different dispute resolution mechanisms, these mechanisms are hardly used simultaneously. The first choice of informal justice can thus be consequential for the overall outcome of dispute resolution. For example, if a family of an assassinated youth resorts to community elders who prescribe a revenge killing, this may lead to further assassinations and the escalation of the blood feud. By forcing respondents to select only one course of legal action, we want to identify situations whereby informal justice is likely to be a default strategy of dispute resolution.

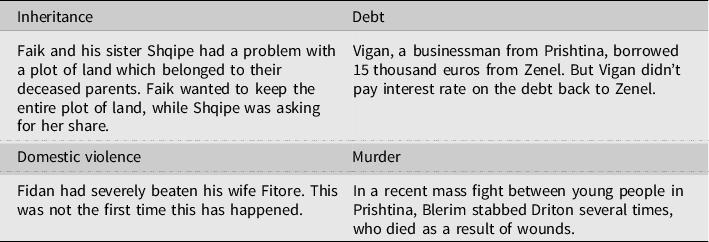

Our vignettes describe four types of disputes (Table 1). Each respondent reads two vignettes, randomly selected. By focusing on different disputes, we ensure variation on the institutional complementarity of formal and informal justice. In civil cases (inheritance and debt), informal justice may serve as a desirable complement to formal justice. In criminal cases (murder and domestic violence), however, state justice is automatically involved and a parallel recourse to informal justice would lead to undesirable jurisdictional infringement (see Matthews, Reference Matthews1989).

Table 1. Types of disputes included in our vignettes

The vignette method permits us to achieve two goals of this study. First is to examine the correlates of respondents’ preferences for informal justice across a wide variety of disputes. An analogous observational analysis would be under-powered, since many respondents have not personally experienced all studied problems. Second, the vignettes allow us to probe into the likely justice behaviors of hypothetical characters whose beliefs and characteristics we can manipulate. These manipulations generate random combinations of distinct circumstances that have been associated with informal justice; for example, a situation in which state justice is perceived as efficient and yet not commonly used by a community (or vice versa). In doing so, our method aims at disentangling different explanations of informal justice.

Results

We analyze the predicted use of informal justice by estimating a preregistered linear model:

whereby Informal justicei is our binary outcome of interest scoring “1” if subject i believes that a given vignette character resolved their dispute through religious or customary justice, and “0” if the subject believes that the vignette character used state justice. All explanatory variables are coded according to the randomization procedure described above (more details in Appendix A.4 in Online Appendix). The models are separately estimated for four types of legal disputes. Footnote 3

Figure 1 shows standardized effects of our experimental primes on the expected choice of informal justice (for accompanying regression table, see Table A1 in Online Appendix). First, we do not find consistent evidence for the effects of vignette characters’ resources on respondents’ assessments of the characters’ choice of informal dispute resolution. The effect of character’s resources is only significant in the case of disputes regarding domestic violence (a 0.06 SD difference).

Figure 1. Experimental primes and the expected use of informal justice by dispute.

Notes: The figure plots point estimates (dots) and 90/95 percent confidence intervals (thick and thin lines, respectively) of regressions of the expected choice of informal justice by a vignette character in the indicated dispute on the indicated experimental prime (i.e. information about the character’s resources and her/his beliefs about state justice). The figure shows standardized effects.

Second, we find that the perceived inefficiency of state justice is associated with higher expectations that a vignette character uses informal justice in all types of disputes. We estimate the respective differences of 0.12 standard deviations (SD) in debt-related disputes, 0.07 SD in inheritance disputes, 0.08 SD in domestic violence disputes, and 0.10 SD in murder disputes.

Third, we find a positive association between local conventions of not using state justice and respondents’ expectation that the characters would rely more frequently on informal justice. Our models estimate the respective differences of 0.06 SD in the case of debt-related disputes, 0.06 SD in domestic violence disputes, and 0.10 SD in murder disputes. In inheritance disputes, the conventions effect is in the same magnitude and direction (0.04 SD) but is not statistically significant at the 95% level (p-value = 0.129).

Extensions. In two not preregistered extensions, we first explore treatment heterogeneity with respect to respondents’ demographics. We do not find consistent evidence that respondents’ own characteristics affect their reactions to the vignette primes (Figure A3 in Online Appendix). Respondents’ resources moderate reactions to the resources prime in two scenarios, but they do so in inconsistent way, either strengthening or weakening the effect of the prime.

Second, we explore whether the conventions prime influences the expected choice of informal justice independently of the other two primes (note that resources and inefficiency concerns may signal likely reasons for why some legal conventions are in place). We test this idea by examining three-way interactions of our vignette treatments (details in Appendix A.6 in Online Appendix). Figure A2 in Online Appendix shows that, in the case of criminal disputes, the effect of conventions on the expected use of informal justice by a vignette character is positive even in scenarios in which we present the character who is rich and who believes that state justice is highly efficient. This pattern is not fully replicated in the case of civil disputes. However, even there, conventions have a positive effect on the expected choice of informal justice by characters who believe that state justice is highly efficient, provided that they are not portrayed as rich.

Beliefs vs. behaviors. Do these associations map onto actual preferences for informal justice and related behaviors? To answer this question, we conduct two additional (not preregistered) tests. First, we study survey respondents’ own preferences for informal justice in a given dispute (Appendix A.7 in Online Appendix). Table A5 in Online Appendix shows that the respondents’ preferences correlate with their mistrust in the state legal system (a proxy for respondents’ first-order beliefs about state justice’s efficiency) and legal preferences of other members of the respondents’ communities (a proxy for local conventions). This result resonates with our vignette findings and is robust to different efficiency and accessibility measures, as shown in Table A6 in Online Appendix.

Second, we collect municipal-level data on actual informal dispute settlement cases in Kosovo. We use information from over 185,000 news items and combine it with aggregate information from our original survey (see Appendix A.11 in Online Appendix). We find that the prevalence of informal justice in a municipality correlates with the average mistrust in state justice and the average preferences for informal justice among the municipal population. This tentative municipal-level evidence is therefore in line with our vignette findings. In Appendix A.11 in Online Appendix, we provide some qualitative evidence which corroborates our quantitative results.

Generalizability. What does the case of Kosovo teach us about informal justice more broadly? The considerations that follow are necessarily tentative. In two not preregistered generalizability tests, we first replicate our analysis using the Asian Barometer data from nine Asian countries (see Appendix A.12 in Online Appendix). Consistent with our vignette results, we find that the Asian Barometer respondents are more likely to contact traditional leaders (a proxy for informal justice) the more they mistrust the formal justice system and the more other people in their localities rely on traditional leaders’ help (Table A11 in Online Appendix). Despite possible measurement and endogeneity issues, this suggestive evidence builds confidence in the generalizability of our findings.

Second, we examine data from the tribal areas in Pakistan (see Appendix A.13 in Online Appendix). Footnote 4 Unlike in Kosovo, in the tribal areas of Pakistan, informal justice is largely a default option for people trying to solve their disputes. Any commonalities between these highly diverse contexts would further underscore the generalizability of our findings. In line with the evidence presented thus far, Table A12 in Online Appendix shows that efficiency concerns and local conventions correlate with informal dispute settlement in the tribal areas of Pakistan.

Conclusion and discussion

Our article contributes to the literature on legal pluralism and extra-legal governance by providing a novel test on three influential explanations of why people rely on informal justice. Our key findings highlight that study subjects associate vignette characters’ use of informal justice with the latter’s perceptions of inefficiency of state justice and local conventions of not using state justice in the characters’ communities. These associations do not vary between civil and criminal disputes. Likewise, the assessments do not seem to be affected by the vignette characters’ imaginable urgency to resolve a given dispute or the likely favorability of specific justice fora. Footnote 5 We find limited support for the conjecture that low economic resource may also be associated with greater reliance on informal justice. Appendix A.10 in Online Appendix delves into related evidence, which largely points to conflicting patterns that reveal heterogeneities worth investigating in future research.

The importance of efficiency concerns and local conventions in choosing informal justice is further confirmed through the (not preregistered) analyses of respondents’ own legal preferences and municipal-level patterns of actual informal dispute settlement cases in Kosovo and ten Asian countries. That said, our conclusions need not apply everywhere. In some contexts, informal justice is associated with particularly harsh punishments and may thus be driven by strong negative emotions, such as anger and related desire for revenge (Garcia-Ponce, Young and Zeitzoff, Reference Garcia-Ponce, Young and Zeitzoff2022).

Before concluding, we briefly discuss a potential concern related to the fact that our vignette primes may not only manipulate the intended information but can also alter other beliefs about fictitious characters. In survey experiments, this issue is known as the information equivalence problem (see Dafoe, Zhang and Caughey, Reference Dafoe, Zhangand and Caughey2018). A related concern is differential informativeness of specific primes. For example, information about the fictitious characters’ resources might not offer such a clear clue to predict their likely course of legal action as the other two primes do. We discuss both problems in Appendix A.9 in Online Appendix and explain why they are unlikely to affect our results, given the extensive triangulation of evidence.

Our study suggests that societies do not remain ungoverned even when the state governance fails or is absent. The void left by the state is filled by local norms and rules. Future research could investigate when and how these informal rules fall into disuse. Improvement of state’s efficiency in justice provision is an obvious indication from our findings. However, in some communities, the state justice may be bypassed irrespective of its efficiency due to local customs. An interesting empirical question is whether highlighting the primacy of state laws in communities traditionally governed by informal rules could realign local customs with formal laws, as proposed by some theoretical models (see Aldashev et al., Reference Aldashev, Chaara, Platteau and Wahhaj2012).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2023.18

Data availability statement

Support for this research came from the British Council, Kosovo. The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KD3ZUN (Krakowski and Kursani, Reference Krakowski and Kursani2023).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Regina Bateson, Diego Gambetta, Edoardo Grillo, Vesa Kelmendi, Pooja Kingsley, Kujtim Koci, Lea Kröger, Olga Mitrovic, Juan Morales, Enzo Nussio, Kazuhiro Obayashi, Isabel Ströhle, seminar participants at the Collegio Carlo Alberto, the 2021 ICSID Conference at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, the University College London, and the 2022 APSA Annual Meeting as well as the editor of the Journal of Experimental Political Science, Bert Bakker, and an anonymous editorial board member for feedback. The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. They contributed equally to the manuscript and are listed in randomized order.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by Collegio Carlo Alberto’s Institutional Review Board and adhered to the American Political Science Association’s Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. Additional information about ethics and consent procedures is available in Appendix A.3 in Online Appendix.