Two salient facts structure a growing literature on gender and politics: First, across countries, there is evidence of widespread gender-based inequities in compensation, opportunities for professional advancement, and assessment of qualifications and performance (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu, Reference Carroll and Sanbonmatsu2013; Lawless, Reference Lawless2015; Mo, Reference Mo2015; Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth, Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018). Second, opportunities to redress such inequities by putting women in charge are limited, since women are underrepresented in politics and leadership positions in business, the academy, and the economy. Previous studies explore gender differences in pursuing positions of power and leadership (e.g., Bennett and Bennett, Reference Bennett and Bennett1989; Burns, Schlozman and Verba, Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Buser, Niederle and Oosterbeek, Reference Buser, Niederle and Oosterbeek2014; Fox and Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2005, Reference Fox and Lawless2014; Fraile and Sanchez-Vıtores, Reference Fraile and Sanchez-Vtores2020; Reuben et al., Reference Reuben, Rey-Biel, Sapienza and Zingales2012). The underrepresentation of women in politics and leadership is both a cause of gender bias and a consequence of its persistence. Can we reduce such gender bias by increasing female participation and cultivating a taste for leadership among women and how?

We address this question with data from South Korea, a country where traditional values and gender stereotypes combine to produce significant gender inequality. The gender wage gap in South Korea is one of the largest among OECD countriesFootnote 1 , and women are greatly underrepresented in politics.Footnote 2 Gender equality issues have become increasingly polarizing.

We begin with the premise that views on gender roles and differences between men’s and women’s participation and leadership in political and public life reflect learned behaviors. Early-life experiences and pre-adult socialization are known to shape how individuals learn and internalize societal norms and expectations (Bos et al., Reference Bos, Greenlee, Holman, Oxley and Lay2022; Fox and Lawless, Reference Fox and Lawless2014). We therefore test whether schools and peer groups shape women’s attitudes about gender, as well as their political participation and leadership behavior. We take advantage of a natural experiment in school assignment in Seoul, South Korea, to examine whether an all-female school environment cultivates women’s political engagement and ambition for leadership while also shaping their gender attitudes and stereotypes. From 1974 to 2009, academic high schools (both public and private) in Seoul admitted students from their local districts using a randomized lottery, which created ideal conditions to identify the causal effects of single-sex vs mixed-sex school environments on women’s attitudes.

Our findings suggest that attending an all-female high school makes women more likely to participate in politics and seek leadership positions, but there is no effect on views regarding gender equality. In other words, all-female schools increase the chances that women voice their opinions and pursue their interests in public life, but these opinions will not necessarily reflect a more feminist policy agenda. Increases in female participation and leadership produced by the experience of single-sex schooling may still provide a pathway to further advance women’s rights and gender equality by promoting women’s descriptive representation and creating more visible female role models in the public arena.

Hypotheses

Previous research argues that, for young women and girls in particular, single-sex education encourages self-expression, participation, and reflection on the role of gender in society (Lee and Bryk, Reference Lee and Bryk1987; Sadker, Sadker and Zittleman, Reference Sadker, Sadker and Zittleman2009; Streitmatter, Reference Streitmatter1999). Holding the type of curriculum and instruction constant, the gender composition of the peer group in schools can shape how adolescents internalize or challenge dominant societal norms, including those related to women’s place in society. For example, single-sex schools provide more opportunities for girls to hold leadership positions, and successful early-life experiences in positions of power, together with the availability of positive female role models, can increase girls’ perception of leadership self-efficacy and cultivate aspirations for leadership later in life (Dasgupta and Asgari, Reference Dasgupta and Asgari2004; Whitt, Reference Whitt1994; Lee and Marks, Reference Lee and Marks1990).

We expect single-sex schools to cultivate non-traditional gender attitudes, but evidence to date is inconclusive. Some argue that all-female schools can create an environment where girls are less subject to the influences of negative gender stereotypes and thus less likely to internalize them (Sadker, Sadker and Zittleman, Reference Sadker, Sadker and Zittleman2009; Streitmatter, Reference Streitmatter1999), while others say that gender-segregated environments may increase endorsement of gender stereotypes due to the increased salience of gender categories and limited interaction with the opposite gender (Bigler and Liben, Reference Bigler and Liben2007; Fabes et al., Reference Fabes, Pahlke, Martin and Hanish2013).

The scarcity of experimental data has impeded advances in understanding the causal effects of single-sex schooling on attitudes or life outcomes, as noted in critical reviews of existing literature (Mael et al., Reference Mael, Alonso, Gibson, Rogers and Smith2005; Pahlke, Hyde and Allison, Reference Pahlke, Hyde and Allison2014). Most previous studies are based on correlational data and do not address selection bias that likely impacts outcomes. A handful of publications leverage the same feature of the random assignment of Seoul high schools as our study, but they focus on educational outcomes such as academic performance, fields of study, and college attendance (Dustmann, Ku and Kwak, Reference Dustmann, Ku and Kwak2018; Pahlke, Hyde and Mertz, Reference Pahlke, Hyde and Mertz2013). No experimental study has investigated how single-sex school environments affect women’s attitudes and behavior in political and public life.Footnote 3 No study has measured effects decades after the end of schooling.

We test four hypotheses: Female graduates of single-sex schools are (1) more likely to participate in civic and political life ( participation hypothesis ), (2) more likely to engage in political activism ( activism hypothesis ), (3) more likely to be interested and involved in leadership roles ( leadership hypothesis ), and (4) less likely to internalize gender stereotypes ( gender stereotypes hypothesis ) than female graduates of coeducational schools.

Data and methods

We use a natural experiment in high school assignment in Seoul that took place from 1974 to 2009. As part of the Korean government’s High School Equalization Policy introduced in 1974, admission tests for all high schools were eliminated and students were randomly assigned to high schools in their residential areas. More details about this policy are provided in Appendix 1.1. Under this policy, students were randomly assigned to attend single-sex or coeducational high schools within their school districts, and the policy applied to all regular academic high schools, where most middle school students matriculate (see Supplementary Table S1), excluding special-purpose high schools (specialized in teaching science, foreign languages, arts, or sports) and vocational high schools. Randomization occurred at the individual student level, and noncompliance was rarely allowed.

The random assignment included both public and private schools. Unlike in the United States, all general high schools, whether they are private or public, charged students the same tuition and fees as set by each of the Metropolitan and Provincial Offices of Education. Moreover, private and public schools offered the same curriculum, as all general high schools were required to follow a nationally standardized curriculum approved by the Korean Ministry of Education. A difference between private and public schools was that private schools have their own procedures for hiring and retaining teachers, whereas public school teachers are rotated to a new school after every 3–5 years. Given potential differences in teacher characteristics between private and public schools, we included an indicator of whether the individual attended a private or public school as a control variable. Private schools are predominantly single sex (see Supplementary Table S3.)

Seoul is one of the regions in the country to have kept this policy of school random assignment the longest, before it modified the policy to allow school choice in 2010. In this study, we focus on people who graduated from Seoul high schools between 1990 and 2010 to ensure that they were included in this natural experiment of random assignment of schools. Through a survey of 3,441 South Korean adults in January 2022, we investigate the causal effects of school environment on participation, leadership, and gender attitudes.Footnote 4 Details of the sample and survey instrument are included in Appendix 2.

Results

Although we are primarily interested in the effects of single-sex schools on female leadership and participation, we also present an analysis of school effects for men. This will help us determine whether single-sex schools have a larger impact on women than men, and whether single-sex schooling can reduce the gender gap in participation and leadership attitudes.

Since the high school assignment was random, our regression estimates should be considered as causal effects. We present results of bivariate regressions as well as models with pretreatment covariates, which may increase the precision of our estimates. The included covariates are pretreatment in the sense that they were generally determined prior to high school assignment, such as parental and family characteristics. Other variables that may affect outcomes but which may be shaped by high school experiences (such as education, income, and current family situation) are not included since they are posttreatment (regression results are in the online appendix). Since school randomization took place for each high school cohort and within each school district, all our regression models include fixed effects for each school district by age cohort. This model specification addresses any year-specific, district-level unobserved heterogeneity, including differences in the probability of assignment to a single-sex or coed school per each year or social stratification by district.

Participation and activism

Our first and second hypotheses ask whether single-sex schooling makes it more likely for women to get involved and take an active role in politics and public life. This analysis is relevant for the gender gap in representation, since civic and political engagement should correlate with political ambition, and people who are more engaged in politics are also more likely to run for office. We asked respondents if they had participated in any of the following nine activities in the past few years: (1) signing a petition, (2) boycotting or intentionally purchasing products for political reasons, (3) attending a political rally, (4) contacting a politician/public official, (5) contributing money to political campaigns, (6) donating money to charity, (7) posting political content online, (8) visiting political websites, and (9) voting in an election (Yes=1, No=0 for each activity).

We summed all nine items to create an index of civic and political participation. Given that women and men may be different in patterns of political participation, we additionally created four separate indices for traditional electoral participation (‘9’); for private activism (‘1’, ‘2’, ‘5’, ‘6’); for collective activism (‘3’); and for political contact (‘4’, ‘7’, ‘8’). Women may be more likely to participate in private types of political activism (see Coffé and Bolzendahl, Reference Coffé and Bolzendahl2010). For the analysis, all indices were rescaled to range between 0 and 1.

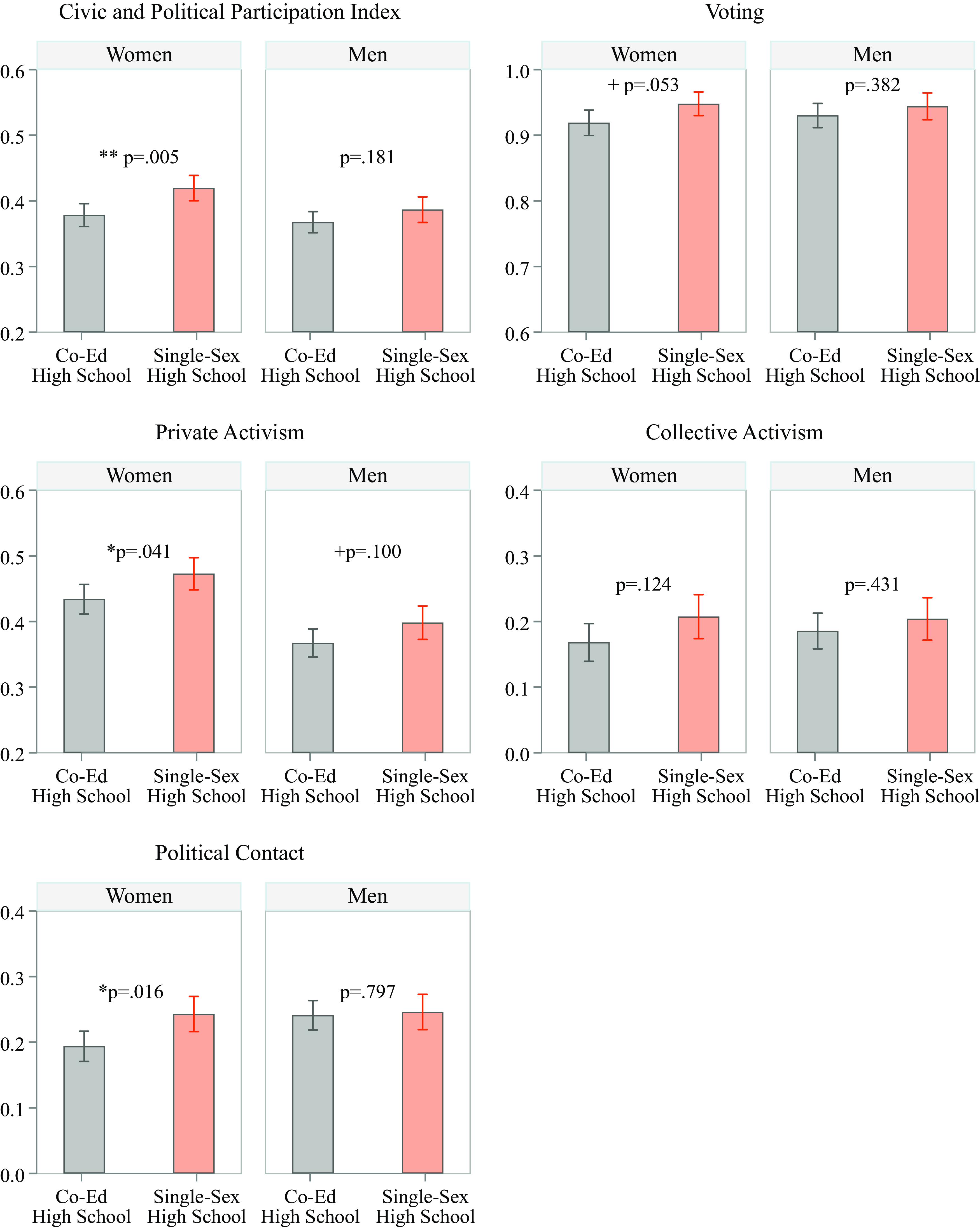

As shown in Fig. 1, we find support for the participation and activism hypotheses. Our tests reveal higher levels of participation among women from single-sex schools than women from coeducational schools in all forms of participation. Single-sex schooling increases women’s overall participation in civic and political activities by 4.1 percentage points (p<0.01).Footnote 5 When it comes to different types of participation, single-sex schooling increases women’s voting by 2.9 percentage points (p<0.10), private activism by 3.9 percentage points (p<0.05), and political contact by 4.9 percentage points (p<0.05).

Figure 1. Effects of Single-Sex Schools on Participation and Activism.

Note. All scales range from 0 to 1. Error bars represent 95% CI. Based on the results shown in Supplementary Tables S5, Model 3.

For collective activism, women from single-sex schools score 3.9 percentage points higher than their coeducational counterparts, but the difference falls short of statistical significance.Footnote 6 For men, the school effect is significant only for private activism: single-sex schools increase men’s private activism by 3.1 percentage points (p<0.10). However, the effect is negligible when we compare men from single-sex and coeducational schools on the other four measures of political participation and activism. Overall, single-sex schooling makes little difference for men’s participation whereas it has significant effects on women.

Leadership

Next, we examine whether single-sex schooling promotes women’s leadership. If our hypothesis holds, women from single-sex schools should be more likely than women from coeducational schools to see themselves as leaders, be more confident in their ability to lead others, and seek and succeed in attaining leadership roles. We use two measures, one that taps into individual preferences and self-efficacy for leadership roles, and one more directly related to behavior, i.e., leadership experience.

Attitudes toward leadership

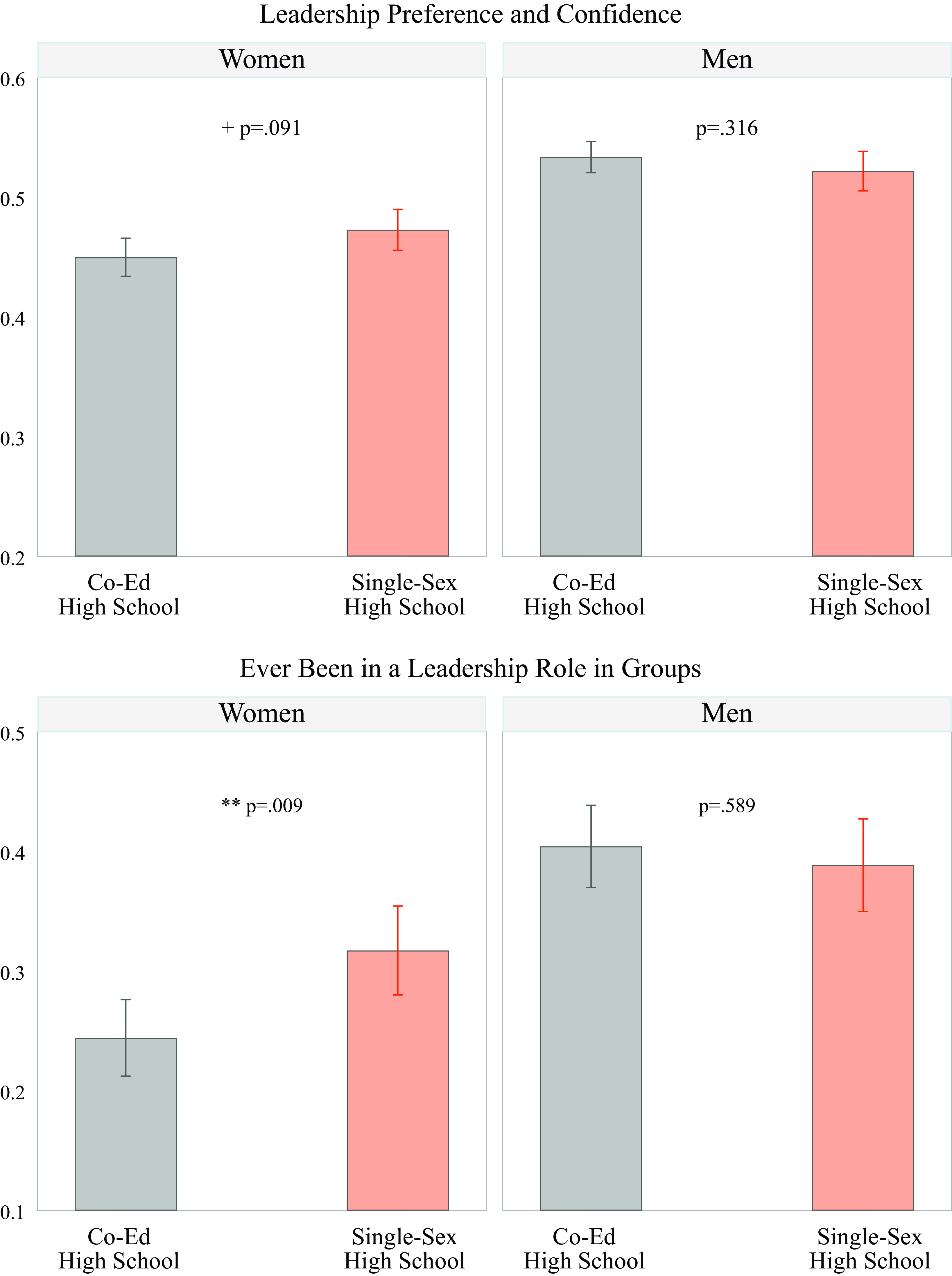

Using items from the motivation-to-lead scale (Chan and Drasgow, Reference Chan and Drasgow2001), we asked respondents to indicate how much they agreed or disagreed with each of the following statements: “Most of the time, I prefer being a leader rather than a follower,” “I am the type of person who likes to be in charge of others,” and “I feel confident that I can be an effective leader in the groups that I work with,” on a seven-point scale. Responses were averaged to form an index of leadership attitudes (α=0.91), where higher values indicate greater interest and confidence in taking on leadership positions. The index was then rescaled to range between 0 and 1. The top panel of Fig. 2 shows that, in line with the prior literature, there are gender differences in leadership attitudes, with women showing lower levels of interest and confidence in leadership roles relative to men.Footnote 7 Our analysis suggests that all-female high schools can help narrow this gender gap by improving women’s leadership aspirations but with only modest success. Female graduates of single-sex schools tend to feel more positive about pursuing leadership than their coeducational counterparts, but the difference is small (2.3 percentage points) and only marginally significant (p=0.09). Single-sex schooling does not have a significant effect on men’s leadership attitudes.

Figure 2. Effects of Single-Sex Schools on Attitudes toward and Experience in Leadership Roles.

Note. Scale ranges from 0 to 1. Error bars represent 95% CI. Based on the results shown in Supplementary Tables S5, Model 3.

Leadership experience

Although the attitudinal measure of leadership ambition provides weak support for our hypothesis, we find much stronger evidence linking single-sex schooling to women’s actual behavior to assume leadership roles. In the survey, respondents were shown a list of groups and organizations (religious groups, professional associations, volunteer organizations, community associations, hobby groups, etc.) and asked to indicate any of the groups of which they are currently a member. For each group indicated, they were asked if they had ever been in a position of leadership in the group (see Appendix 2.2).

We find that single-sex schooling has a significant and positive effect on women’s participation in leadership roles. As shown in the bottom panel of Fig. 2, women who graduated from single-sex high schools are 7.3 percentage points more likely to have held a leadership role than women from coeducational high schools (p<0.01).Footnote 8 In contrast, the difference between men from single-sex and coeducational schools is not statistically significant. These results support our hypothesis. Although men still outnumber women in taking leadership roles in groups and organizations, single-sex schooling helps reduce this gender gap.

Gender attitudes

Our last hypothesis explores whether single-sex schools challenge gender stereotypes and instead promote more progressive gender attitudes. We measured two attitudes related to gender stereotyping—hostile sexism and traditional gender role beliefs. Using a five-item version of the hostile sexism scale (Glick and Fiske, Reference Glick and Fiske1997; Schaffner, Reference Schaffner2021), we asked respondents to indicate how strongly they agreed with each of the following statements on a seven-point scale: “Women are too easily offended,” “Most women fail to appreciate fully all that men do for them,” “Women seek to gain power by getting control over men,” “Women exaggerate problems they have at work,” and “Once a woman gets a man to commit, she usually tries to put him on a tight leash,” and then combined the items to create a single index (α = 0.92). Respondents were also asked about their degree of agreement with statements such as “It is more important for a wife to help her husband’s career than to pursue her own career,” “A husband’s job is to earn money; a wife’s job is to look after the home and family,” which were then combined into an index of traditional gender role beliefs (α = 0.73).

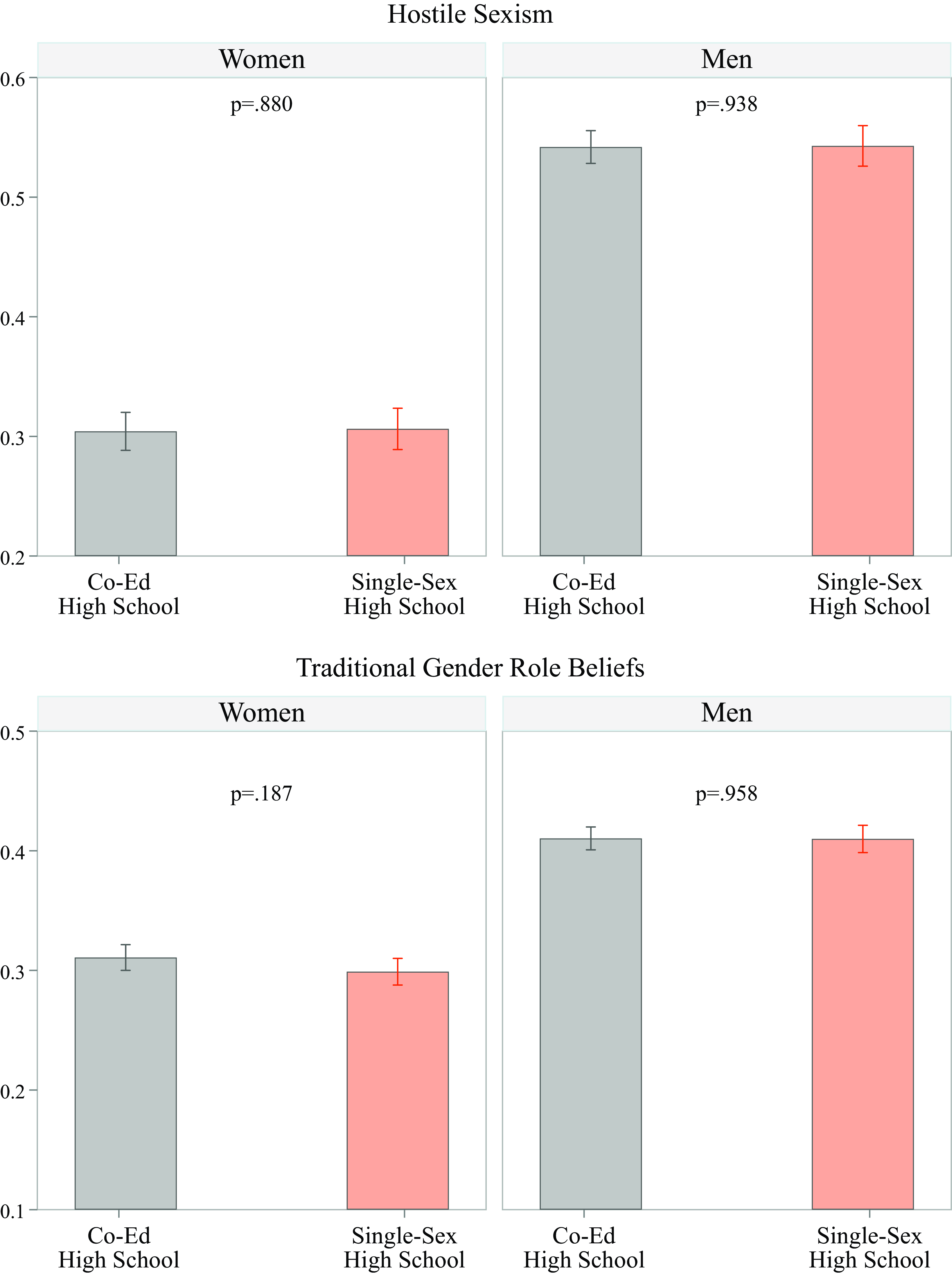

Figure 3 presents the estimated effects of single-sex schooling on hostile sexism and traditional gender role beliefs. Women score much lower than men on these measures, exhibiting less sexist views and being less supportive of traditional gender roles. To our surprise, however, the analysis shows no significant difference between graduates of single-sex and coeducational schools in their gender attitudes. We find no significant effect of single-sex schools on either measure for women or men.

Figure 3. Effects of Single-Sex Schools on Hostile Sexism and Traditional Gender Role Beliefs.

Note. Scale ranges from 0 to 1. Error bars represent 95% CI. Based on the results shown in Supplementary Table S7, Model 3.

Conclusion

Across countries, women are generally underrepresented in politics, senior management and leadership positions in business and industry, and tenured positions in several fields in the academy. One possible way to change this pattern is to inculcate women with the self-confidence, ambition, and training necessary to compete for leadership positions and encourage them to participate more in politics and to voice their opinions. Early-age interventions are likely to be particularly effective in that regard.

Analyzing experimental data from South Korea, our study suggests that early-age interventions during school years can provide a pathway to reduce the gender gap in leadership and participation. An unusual natural experiment in school assignment in South Korea allowed us to estimate the causal effects of exposure to an all-female school environment, and we found that single-sex schools increase women’s leadership aspirations, civic engagement, and political participation; moreover, these effects last for years, and sometimes decades after graduating from school. Our survey respondents are currently in the 30–50 age range; this indicates that early-life experiences in school have durable effects that persist into adulthood. We note that, across countries, same sex schooling for women was not associated with promoting feminist ideas until recently. The fact that we find some movement on women’s participation with random assignment to these schools suggests that effects are likely larger in settings where the school explicitly promotes feminist ideas and parents choose the schools their daughters enroll in by selecting schools that aim to empower young women.

More research is needed to uncover the precise mechanism for this effect. A productive approach would be to contrast the findings of several studies that take advantage of the randomization of students in South Korea to analyze different outcomes – such as school performance, university enrollment, or competitiveness – to suggest possible pathways for the downstream effects we identify. All-female schools may affect women’s attitudes and behavior by providing more opportunities for and experiences with leadership to female students, which can give them the assurance they need to compete more effectively later in life. They also expose girls to an all-female peer group in which they are less likely to be subjected to negative stereotypes. It is possible that these peer group effects are amplified by unobserved school-level differences (if, for example, teachers and administrators are more likely to be female in single-sex schools). These mechanisms are likely clustered together and combine to produce an overall positive impact of learning in a same-sex environment for girls. The schools’ effects on increased female participation and activism, however, may not translate into a feminist agenda, as female graduates of single-sex schools do not hold more progressive views about gender equality than female graduates of coeducational schools. Young women from single-sex schools may feel more self-assured and comfortable seeking leadership positions compared to their coeducational counterparts, without necessarily perceiving leadership and participation as a conscious rejection of regressive gender stereotypes. Our study suggests that early age interventions can help produce women who lead and are active in political and public life; this can contribute to women’s descriptive representation and create more role models, which can inspire other women and girls to pursue positions of power and influence.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2025.6.

Data availability

Replication data for this article are available in The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: doi:10.7910/DVN/YZ1W51. See Lee and Sambanis (Reference Lee and Sambanis2025).

Acknowledgements

For useful discussions and comments, we thank Jere Behrman, Danny Choi, Jaesung Choi, Alexander Coppock, Eugen Dimant, Emily Hannum, Dan Hopkins, Joshua Kalla, Jennifer Laweless, Diana Mutz, Hyunjoon Park, Sun Young Park, Susanne Schwarz, Matthew Simonson, Dawn Teele, Sule Yaylaci, and Anna Zhang. This paper is based on work the authors conducted at the University of Pennsylvania, prior to their current employment. The views presented in this publication are solely those of the authors and do not represent the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Support for this research was provided by the Identity & Conflict Lab.

Competing interests

We have no conflicts of interest to report for this research.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania (protocol number: 850433). This study adheres to APSA’s Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. More information on the ethical practices related to this study can be found in the Online Appendix.