Introduction

The American public is not well informed about immigration (Ekins and Kemp Reference Ekins and Kemp2021; Lutz and Bitschnau Reference Lutz and Bitschnau2023). Although even experts can disagree on the issue, most Americans hold factually incorrect beliefs about the issue. Americans tend to exaggerate immigrants’ population size (Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019), unfavorable characteristics such as crime rates (Light, He, and Robey Reference Light, He and Robey2020), and socio-cultural differences with the native population (Flores and Azar Reference Flores and Azar2023). Various attempts to change people’s minds on policy by providing information or correcting these misperceptions have been, with few exceptions (Abascal, Huang, and Tran Reference Abascal, Huang and Tran2021; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Ahlstrom-Vij, Rolfe and Runge2023; Facchini, Margalit, and Nakata Reference Facchini, Margalit and Nakata2022; Haaland and Roth Reference Haaland and Roth2020), unsuccessful (Hogue Rovelo, Hyde, and Landgrave Reference Hogue Rovelo, Hyde and Landgrave2024; Hopkins, Sides, and Citrin Reference Hopkins, Sides and Citrin2019; Kustov, Laaker, and Reller Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021; Lutz and Bitschnau Reference Lutz and Bitschnau2023). It is possible that this has been the result of focusing on beliefs about immigration that are too crystallized (Tesler Reference Tesler2015) or not providing novel relevant information (Coppock Reference Coppock2023). Additionally, raising support for increasing future immigration flows may be harder than raising support for helping existing immigrants (Margalit and Solodoch Reference Margalit and Solodoch2022; Ruhs Reference Ruhs2013).

Unlike most prior efforts, our study focuses on changing people’s understanding of US immigration admission policy by providing novel information about the difficulties involved in the legal immigration process. We focus on legal immigration because it is the primary means by which migrants arrive in the United States, though future work can also extend our study to irregular migrants (e.g., undocumented migrants and refugees). Beliefs about the immigration process’ difficulty should be relatively malleable to new information because it is a topic that receives little attention and thus where beliefs are not crystallized. We argue that informing Americans about the difficulty of legally immigrating, which many are unaware of, could be an effective way to raise public support for more open immigration admission policies. We then test and confirm this expectation using a large representative survey experiment that informs respondents about the administrative burdens and restrictions of the current US immigration system. We are also among the first to descriptively assess people’s (mis)perceptions about the legal US immigration process in a representative sample. Compared to existing approaches trying to convince skeptics that immigration is or immigrants are good, the results indicate that our approach of giving a new perspective that immigration is difficult has more promise to change people’s policy preferences.

US immigration is a complex policy domain defined by numerous laws and controlled by multiple government agencies with overlapping authority (Tichenor Reference Tichenor2002; Lee, Landgrave, and Bansak Reference Lee, Landgrave and Bansak2023). Even if one only considers federal laws governing the admission of legal family and employment-based immigration, the focus of our paper, the immigration process is “difficult.” The process is both administratively burdensome – the complexity of the process and what it takes to go through it (Moynihan, Gerzina, and Herd Reference Halling, Herd and Moynihan2022; Bier Reference Bier2023) – and restrictive – in terms of who is eligible to go through the process in the first place (Bier Reference Bier2023; Peters Reference Peters2017). While we follow public administration literature and differentiate between these two distinct concepts (Halling, Herd, and Moynihan Reference Halling, Herd and Moynihan2022), we are agnostic about which of these elements is more important to people’s preferences.

Given low levels of political knowledge (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016; Somin Reference Somin2016), most people likely have a limited understanding of the immigration process or the burdens involved. As a result, voters may form strong preferences on what the government should do about immigration without knowing what the government already does. Americans tend to assume that their immigration system is much more straightforward and open than it is (Ekins and Kemp Reference Ekins and Kemp2021, also see Table 1). One recent poll showed that most voters across parties incorrectly believed that it would only take a few years to receive a green card for a Mexican sibling of a US citizen (Orth Reference Orth2022). The correct answer of 20 years was given by only 1% of respondents. Strikingly, the vast majority – including Republicans – believed it should only take a few years.

Table 1. Information treatment conditions

This existing fragmented evidence suggests that people’s misperceptions about immigration policy may be deeper than misperceptions about immigrant characteristics or immigration effects. Consequently, there may also be more room for information to update people’s beliefs about immigration policy to change their preferences than in the case of these other facts. In line with this idea, there is recent evidence that policy-oriented information can change minds about non-immigration policies (Halling, Herd, and Moynihan Reference Halling, Herd and Moynihan2022; Keiser and Miller Reference Keiser and Miller2020; Nicholson-Crotty, Miller, Keiser, et al. Reference Nicholson-Crotty, Miller and Keiser2021; Thorson Reference Thorson2024) and irregular immigration (Thorson and Abdelaaty Reference Thorson and Abdelaaty2022). It is important to replicate these findings on the broader domain of legal immigration policies using a representative sample.

Interventions that make existing knowledge accessible should be less effective and durable than information provision interventions that instead make new knowledge applicable (Coppock Reference Coppock2023; Haaland, Roth, and Wohlfart Reference Haaland, Roth and Wohlfart2023). Information interventions should also be more effective for policy persuasion than perspective-taking approaches that are more suited for reducing group prejudice (Abascal, Huang, and Tran Reference Abascal, Huang and Tran2021). Among possible information interventions, non-judgmental and verifiable narratives (Dennison Reference Dennison2021) that can shift people’s understanding of immigration should also be preferable to fact-checking approaches that simply attempt to correct people’s misperceptions about various, often already crystallized, immigration facts (Abascal, Huang, and Tran Reference Abascal, Huang and Tran2021).

We argue that telling respondents about the administrative burdens and restrictiveness of the US immigration process can be such an “eye-opening” information intervention. Importantly, to the extent that such information can successfully change people’s minds, it should work by generating new knowledge or otherwise updating people’s respective empirical beliefs about the difficulty involved in the immigration process. We test the effect of informing the public about the difficulty of immigrating on immigration attitudes using a nationally representative survey experiment (YouGov, N = 1000) (Iyengar, Lelkes, and Westwood Reference Iyengar, Lelkes and Westwood2023) that informs respondents about administrative burdens and restrictions of the current US immigration system. Specifically, we will test the following hypotheses:

H1: Receiving relevant information about the difficulty of legal immigration to the United States will increase respondents’ awareness of this difficulty.

H2: Receiving relevant information about the difficulty of legal immigration to the United States will increase respondents’ support for more open legal immigration policies.

In addition to our experimental results, we also descriptively assess the public’s (mis)perceptions about the US legal immigration admissions process. To do that, we ask our respondents to guess the average waiting time for different categories of foreigners who want to immigrate legally. Since we want to generalize the available evidence about particular idiosyncratic categories (Orth Reference Orth2022), we ask about multiple groups based on their skills, availability of job offers, and familial relationship to US citizens. In particular, the respondents are asked to guess how long it takes for an adult sibling of a US citizen, an aunt or uncle of a US citizen, a doctor without a job offer, a famous athlete or artist, or a nanny with a job offer to legally migrate to the United States (see appendices for the survey instrument).

Methods

We pre-registered our study on Open Science Framework (OSF)Footnote 1 and uploaded replication materials on Harvard Dataverse (Kustov and Landgrave Reference Kustov and Landgrave2024). The sample of N = 1000 was collected as a part of a larger omnibus survey by YouGov from May 26 to June 2, 2023 (Iyengar, Lelkes, and Westwood Reference Iyengar, Lelkes and Westwood2023). The respondents were matched to a sampling frame on gender, age, race, and education, constructed by stratified sampling from the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS). While all our analyses employed the standard post-stratification weights provided by YouGov, removing these weights does not impact our results.

Based on best ethical practices in experimental political science (Costa et al. Reference Costa, Crabtree, Holbein and Landgrave2023; Desposato Reference Desposato2015; Landgrave Reference Landgrave2020), ethical concerns regarding our study are minimal. Respondents provided informed, voluntary, and affirmative consent to participate in the research study and no deception was used. Respondents were never placed in any danger or risk beyond those experienced in routine clerical work. Per YouGov terms, respondents did not receive monetary compensation. YouGov respondents agree to participate in surveys without compensation although they may receive gifts at YouGov’s discretion. Our survey was fielded as part of a larger omnibus survey, the Polarization Research Lab’s America’s Political Pulse Survey, and we did not have control over what compensation respondents did or did not receive.

Pre-treatment, respondents were asked about their factual knowledge of immigration visa policies. Respondents were then randomly exposed to one of the informationalFootnote 2 treatments with encouragement to read it carefully. Post-treatment, respondents completed a set of survey items measuring their immigration preferences (main outcomes) and beliefs about immigration difficulty (secondary outcomes which also acted as manipulation checks).

Our two “burdensome” and “restrictive” 150-word treatments built on the publicly available information (Bier Reference Bier2023) about various aspects of the immigration process in a form of an accessible, verifiable, and non-judgmental narrative (Dennison Reference Dennison2021). The burdensome treatment conveyed that immigration application and legal fees amount to thousands of dollars and going through the right process takes many years. The restrictive treatment conveyed that there is a limited number of immigrant visas available each year and that, depending on one’s origin country, some immigrants may not be able to obtain permanent residency for which they are otherwise eligible.

Using simple randomization, 1/3 of respondents was exposed to each of the two treatments plus a further 1/3 of respondents were exposed to a placebo condition – a text mentioning policy-neutral facts about immigration.Footnote

3

To minimize measurement error, the survey included multiple previously validated immigration preference items

![]() $\left( {\alpha = 0.76} \right)$

and novel immigration belief items summarized as 0–1 indices. Given the random assignment, to test our two hypotheses we simply compared the mean values for relevant indices between the combined experimental and the control groups using a standard difference-in-means estimator.

$\left( {\alpha = 0.76} \right)$

and novel immigration belief items summarized as 0–1 indices. Given the random assignment, to test our two hypotheses we simply compared the mean values for relevant indices between the combined experimental and the control groups using a standard difference-in-means estimator.

Results

Documenting immigration policy knowledge. Our descriptive results confirm that the US public significantly lacks knowledge about current immigration admission policies, even more so than about immigrant characteristics. Table 2 shows and provides t-tests for subgroup differences in immigration visa policy knowledge across the following dichotomized sociodemographic groups: gender (female vs male), age (

![]() $ \le $

40 vs 40+), race (non-Hispanic white vs non-white), language (Spanish vs non-Spanish speakers), educational attainment (college degree or more vs less than college), income (low vs high), party identification (Republican vs Democrat), and ideology (conservative vs liberal). To make comparisons more general and informative, we test for differences in knowledge about whether the uncles and aunts of a US citizen are eligible for a green card (arguably one of the most straightforward questions in our battery), the average correct across the knowledge battery, and the average correct across the knowledge battery including almost close answers.

$ \le $

40 vs 40+), race (non-Hispanic white vs non-white), language (Spanish vs non-Spanish speakers), educational attainment (college degree or more vs less than college), income (low vs high), party identification (Republican vs Democrat), and ideology (conservative vs liberal). To make comparisons more general and informative, we test for differences in knowledge about whether the uncles and aunts of a US citizen are eligible for a green card (arguably one of the most straightforward questions in our battery), the average correct across the knowledge battery, and the average correct across the knowledge battery including almost close answers.

Table 2. (No) subgroup differences in immigration policy knowledge. The table shows 95% CI and p values from survey-weighted t-tests for binary subgroup differences. For details, see supplementary material

Only

![]() $8 \pm 1.5{\rm{\% }}$

of respondents correctly answered that aunts and uncles of US citizens are not eligible for legal family-based immigration. We believed the aunt/uncle question would be the easiest question to answer, but as the data show relatively few respondents guessed correctly. The average correct response rate across all immigrant admission categories is

$8 \pm 1.5{\rm{\% }}$

of respondents correctly answered that aunts and uncles of US citizens are not eligible for legal family-based immigration. We believed the aunt/uncle question would be the easiest question to answer, but as the data show relatively few respondents guessed correctly. The average correct response rate across all immigrant admission categories is

![]() $25{\rm{\% }}$

, just slightly better than what we would expect from random guessing (20%). Even if we include ’almost’ correct answers, answers in the same direction as the correct answer, the correct rate only slightly raises to

$25{\rm{\% }}$

, just slightly better than what we would expect from random guessing (20%). Even if we include ’almost’ correct answers, answers in the same direction as the correct answer, the correct rate only slightly raises to

![]() $40{\rm{\% }}$

(with the correct guess rate by chance of 20%).

$40{\rm{\% }}$

(with the correct guess rate by chance of 20%).

Importantly, our knowledge battery confirms that this lack of knowledge is equally widespread across all major sociodemographic and political categories. Young and old, white and non-white, rich and poor are all ignorant of current immigration admission policies. There is some evidence that college-educated, liberal, and Democrat respondents are somewhat more knowledgeable but these differences of a few percentage points are arguably not substantively important. There is also only a similarly minor difference in knowledge based on respondents’ racial attitudes (see pilot study appendix). These findings further suggest that providing information about immigration policies should be novel for most respondent groups.

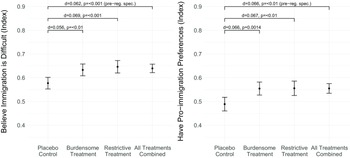

Effects of providing immigration policy information. In line with our pre-registered hypotheses and empirical specifications, our main results show that providing novel information about immigration difficulty is effective (see Figure 1 and Table A1, Supplementary material). After reading about the current restrictions or their administrative burden, respondents were significantly more likely to believe that immigration is difficult (0.062 on a 0–1 scale or Cohen’s

![]() $d$

of 0.27) and report pro-immigration policy preferences (0.066 on a 0–1 scale or Cohen’s

$d$

of 0.27) and report pro-immigration policy preferences (0.066 on a 0–1 scale or Cohen’s

![]() $d$

= 0.25).Footnote

4

Substantively, this amounts to

$d$

= 0.25).Footnote

4

Substantively, this amounts to

![]() $11 \pm 6$

percentage-point (28%) more respondents believing that legal immigration is burdensome or restrictive (given the baseline of 40%) and

$11 \pm 6$

percentage-point (28%) more respondents believing that legal immigration is burdensome or restrictive (given the baseline of 40%) and

![]() $13 \pm 6$

percentage-point (35%) more respondents preferring to increase legal immigration or make it easier (given the baseline of 35%).

$13 \pm 6$

percentage-point (35%) more respondents preferring to increase legal immigration or make it easier (given the baseline of 35%).

Figure 1. (Positive) effects of immigration policy information on beliefs and preferences. May–June 2023 Main Study (YouGov, N = 1000). This figure depicts the pre-registered hypotheses tests. Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Our additional exploratory analysis suggests that both treatments had a statistically similar positive effect across distinct immigration preference and belief outcomes (see appendices section 2 – additional figures and tables). At the same time, the treatment effects remain the same when we include controls for major pre-treatment covariates (see Table A1 in Supplementary material). Although our sample size was not large enough to detect small between-treatment differences or interaction effects, the exploratory analysis indicates that the treatment effects were similarly positive for most major political and socioeconomic groupings, including both Democrats and Republicans and across the ideological spectrum (see Tables A2–A5 and Figures A2–A5 in Supplementary material).

Additional pilot results To ensure the project’s feasibility and pretest original items, we also conducted a pilot survey experiment in November 2022 using a large, diverse online sample (US Prolific, N = 912). The pilot study was near-identical in both design and results of the main study. Notably, the Prolific study had a single, shorter preference outcome (preferring increasing immigration) and included a political cartoon of a nondescript person lost in an ’immigration maze’ with the information treatment conditions (see appendices for further details about the pilot study design). The image was intended to emphasize the difficulty inherent in the US immigration system. Despite the exclusion of the image in the follow-up study, the same general results (see Figure 2) are present in the pilot and main studies. That is, after reading about the current restrictions or their administrative burden, respondents were similarly more likely to believe that immigration is difficult (0.072 on a 0–1 scale) and report preferring increasing immigration levels (0.062 on a 0–1 scale). This increases our confidence that our results are not being driven by specific wording and/or imagery alone.

Figure 2. (Positive) effects of immigration policy information on beliefs and preferences. November 2022 Pilot (Prolific, N = 912). Bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The pilot results also suggested that, even in the relatively liberal and educated Prolific sample, few people were knowledgeable about immigration policy.Footnote 5 On average, respondents provided correct answers 32% of the time, slightly above the 20% expected by guessing alone (and above the 25% estimate from our nationally representative sample). Furthermore, similar to our main results, none of the major socioeconomic or political covariates were significantly predictive of immigration policy knowledge (including education, partisanship, and even racial resentment measures).

Discussion

Many individuals and organizations advocate for more open immigration admission policies, driven by the beliefs and evidence that immigration generally benefits all parties involved and thus should be less restricted. Yet, despite these well-intentioned efforts, many voters remain skeptical. While there has been much research on how one can change minds, it is still unclear whether it is possible to persuade voters to support liberalizing legal immigration policies. We argued that informing Americans about the difficulty of legally immigrating – which many are simply not aware of – could be such an effective way to raise public support for more open immigration admission policies. We then showed that a short factual narrative about immigration policy burdens and restrictions could convince at least some of the current skeptics to reconsider their position on the issue, with about 13 percentage points (or 35%) more respondents displaying pro-immigration attitudes. Importantly, the intervention has successfully changed peoples’ minds by generating new knowledge or otherwise updating their respective empirical beliefs about the difficulty involved in the immigration process. These results are encouraging given that many previous immigration information experiments find that respondents update their empirical beliefs but not policy preferences.

Of course, our findings are not without limitations and there are several extensions worth pursuing. Future research can explore whether the effects observed here are long-lasting or can withstand counter-information or counter-framing. Our results suggest that providing information about current immigration policies and their difficulty can affect a few percent of voters in the short run, but it is important to acknowledge that immigration attitudes are generally stable in the long run (Kustov, Laaker, and Reller Reference Kustov, Laaker and Reller2021). Although it is possible that the effects displayed here would be damped in real-world campaigns (Broockman and Kalla Reference Broockman and Kalla2022), we are optimistic that an effect would persevere given the relative novelty of the information presented. Ultimately, any robust positive change in policy would also require compromising with those voters who oppose immigration regardless of available information (Helbling, Maxwell, and Traunmüller Reference Helbling, Maxwell and Traunmüller2023; Kustov Reference Kustov2025).

Future research could explore the relative effect strength of various treatment variations and possible subgroup effects in larger representative samples in the United States or other countries. Stimuli and placebo sampling, using multiple treatments, would be especially helpful in addressing concerns that specific phrases are driving the observed effects. There is suggestive evidence that informational treatments may have differing effects among conservatives, and other demographic subgroups (Chan, Raychaudhuri, and Valenzuela Reference Chan, Raychaudhuri and Valenzuela2023). There is also evidence that, depending on the policy environment itself, voters in some countries and contexts can be systematically more knowledgeable about immigration and its benefits than others (Donnelly Reference Donnelly2017; Liao, Malhotra, and Newman Reference Liao, Malhotra and Newman2020).

Our focus in this manuscript was on changing attitudes toward legal immigration policies. We did not compare (the effects of information about) administrative burdens in immigration to other policies or test whether our informational treatment might also work with other types of immigration or immigrant groups like undocumented migrants or refugees (Bansak, Hainmueller, and Hangartner Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2017; Thorson and Abdelaaty Reference Thorson and Abdelaaty2022). We focus on voters’ attitudes toward legal immigration in particular (as opposed to undocumented immigration or immigration in general as it is common in the persuasion literature) because legal pathways remain the primary means by which the US regulates the long-term admission of non-citizens into the country. Although the US government also has distinct policies concerning irregular migrants, these policies are largely contingent on the number of allowed legal immigrants (Bier Reference Bier2023; Ruhs Reference Ruhs2013) We also did not consider how voters’ or migrants’ inter-sectional identities (e.g., based on gender, religion, race, or ethnicity, see Choi, Poertner, and Sambanis (Reference Choi, Poertner and Sambanis2023)) may moderate our findings. Exploring these and other heterogeneous effects is beyond the scope of the present manuscript.

Finally, several plausible mechanisms could explain our results, even considering the manipulation check evidence of increased awareness of immigration difficulty. The information treatments may alert people to perceived injustices in the current system, leading to support for reform as a means of empathizing with immigrants’ plight (Williamson et al. Reference Williamson, Adida, Lo, Platas, Prather and Werfel2021) or creating a more equitable system aligned with American values (Levy and Wright Reference Levy and Wright2020). Alternatively, the treatments might highlight systemic inefficiencies, prompting support for reform to improve functionality and better serve American interests (Kustov Reference Kustov2021).

We intend to explore these and other extensions in future work. Still, given that the attitudes toward future immigrants may be generally harder to change than toward present migrants (Margalit and Solodoch Reference Margalit and Solodoch2022), our findings carry the potential for wider applicability. Our approach also provides the foundation for a robust research program exploring policy persuasion on immigration and other issues.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2024.21

Data availability

The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SCX187.

Acknowledgements

We thank seminar participants at the Politics of Race, Immigration, and Ethnicity Consortium (PRIEC), the Junior Americanist Workshop Series (JAWS), the American Political Science Association (APSA) annual meeting, and others for valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this manuscript. All remaining errors are our own.

Funding statement

This research was supported by survey space in the Polarization Research Lab’s Partisan Animosity Survey Time Sharing (PASTS).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

This research complies with all relevant ethical regulations and with APSA’s Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. The study was approved by IRB at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and the University of Missouri. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. YouGov compensates participants with reward points that can be redeemed for cash.