INTRODUCTION

China has risen dramatically in the past few decades, becoming the second largest economy in the world (the largest by purchasing power parity) and a crucial player in global affairs. Yet Chinese citizens, including middle-class professionals, students, and the wealthy class, are flocking abroad in unprecedented numbers and, in many cases, permanently emigrating to foreign countries. China now sends more emigrants to the US each year than any other country, including Mexico and India (Shah Reference Shah2015). Chinese students are the largest group of foreign students not only in the US (where they make up 29 percent of the international student population) but also in the entire English-speaking developed world, as well as many other countries such as France, Germany, Italy, and Japan (Economist 2015; Jordan Reference Jordan2015). An often-cited recent survey shows that about 47 percent of China's wealthy individuals have plans to move abroad (Yan Reference Yan2014).

While some commercial studies have analyzed why members of China's wealthy class (want to) move abroad (Bain & Company 2013; Hurun Report Reference Report2014), the motivations of ordinary people and the middle class for going abroad have not been subjected to systematic investigation, except for some journalistic accounts (e.g., Economist 2014a, 2014b, 2015). More importantly, the limited inquiries that have been made into Chinese people's motivations for going abroad almost exclusively focus on their desires for better social and economic conditions, including education, environment, food safety, and, for the wealthy class, investment and risk diversification. While it is clear that aspirations for better social environment, education, and living conditions are fundamental to Chinese citizens’ desire to go abroad, little consideration has been given to the question of whether Chinese citizens have sufficiently accurate information about foreign countries when they contemplate leaving China.Footnote 1 For most ordinary Chinese people who have no first-hand experience of living abroad (or even of overseas travel), however, the most important factor behind their intentions about moving abroad is not the objective social and economic conditions in foreign countries but rather their perceptions of such conditions. In other words, what influences people in leaving China is not just their preferences and aspirations but also their information and perceptions about what life in the outside world, particularly advanced Western countries, is like.

A natural and important question, then, is whether and how perceptions about foreign socioeconomic conditions affect people's interest in going abroad. In particular, do more positive perceptions of foreign countries lead to higher inclinations to leave China? Will correcting people's misinformation about foreign countries change their interest in going abroad? Addressing these questions will not only provide insights about one of the most important social trends in contemporary China; it also has significant theoretical value for the international migration literature and for our understanding of the political and social effects of (mis)information, as will be discussed later.

To understand the relationship between ordinary Chinese citizens’ knowledge and perception of foreign counties, on the one hand, and their inclination to go abroad, on the other, I conducted two studies, each consisting of about 1,000 participants: a survey experiment with Chinese internet users from diverse sociodemographic backgrounds, and a survey of students in a mid- to upper-tier Chinese university. The studies show that Chinese citizens with more positive perceptions of foreign socioeconomic conditions have stronger inclinations to leave China. More importantly, the survey experiment shows that there is a causal effect from rosier perceptions of foreign conditions to higher interest in going abroad, since correcting the misinformation of the respondents who overestimated foreign socioeconomic conditions reduced their interest in leaving China. On the other hand, both studies show that international political knowledge, as measured by familiarity with political affairs and leaders in foreign countries, does not have a significant or consistent relationship with one's interest in going abroad.

These results not only demonstrate that information and perceptions, sometimes erroneous ones, influence Chinese people's interest in going abroad; they also suggest that their motivations for leaving China are more socioeconomic than political in nature, at least in terms of one's understanding of foreign countries. This is important because, given that China is both a developing and non-democratic country, Chinese people may want to exit for political, economic, or both reasons. The current research shows that, at least for the time being, socioeconomic aspirations dominate political yearnings in China. This is different from a country like North Korea, where political considerations are also important in people's exit decisions (Chang, Haggard, and Noland Reference Chang, Haggard and Noland2008; Haggard and Noland Reference Haggard and Noland2006).

This article does not claim to reveal all factors shaping the preferences of Chinese citizens, nor do the results imply that with accurate information Chinese people will not be going abroad. After all, given that China's overall socioeconomic development, let alone the level of freedom and democracy, still lags behind advanced Western countries, many people in China have ample reasons for pursuing life or a career in a different country. But the results do suggest that many Chinese people would have different levels of inclination to go abroad if they had more accurate information about the outside world, and that the current trend of Chinese people flocking abroad does not always represent informed decisions to vote with their feet, as is often assumed by the conventional wisdom.

More broadly, this research is part of a new and rising literature on the political and social effects of citizen misinformation and misperception. This emerging literature has shown that people often have vastly incorrect beliefs about basic policy and socioeconomic facts of their own country and foreign countries, and these misbeliefs have significant and hitherto poorly understood political and social effects, including citizens’ support of their government (Gilens Reference Gilens2001; Huang Reference Huang2015; Kuklinski et al. Reference Kuklinski, Quirk, Jerit, Schwieder and Rich2000). However, to use Albert Hirschman's (Reference Hirschman1970) classic terminology, while this literature has examined how misinformation and misperceptions affect citizens’ “voice” and “loyalty” to their own country and government, no study so far has analyzed how misinformation affects people's inclination to leave their country to pursue life in a foreign land, i.e., the “exit” decision. The current research represents the first effort to understand this important question.

The next section lays out the article's hypotheses and explains the variables. The following two sections report results from the online survey experiment and the college survey respectively. The last section discusses the findings and concludes.

HYPOTHESES AND VARIABLES

Theory and Hypotheses

Research in social psychology, economics, and political science has shown that people's evaluations of themselves and their communities are not just based on objective conditions, but are also influenced by subjective social comparisons (for two classic studies, see Festinger Reference Festinger1954 and Stouff et al. Reference Stouff, Lumsdaine, Lumsdaine, Williams, Smith, Janis, Star and Cottrell1949). For example, Easterlin (Reference Easterlin1995) argues that an increase in the income of all will not lead to a long-term increase in happiness for all, as individuals’ feelings of happiness are affected by comparisons with others. Kayser and Peress (Reference Kayser and Peress2012) show that voters often judge their national economy on the basis of the global situation rather than in isolation.

While relative deprivation and social comparison theories have been well articulated, previous studies usually assume that people have correct information about other people or societies on which they can base comparisons. More recently, however, it has been shown that citizens often have wrong beliefs about what other countries are like, and such beliefs influence how they evaluate their own country and government (Huang Reference Huang2015). In particular, more positive perceptions and especially overestimation of socioeconomic conditions in Western countries can lead many Chinese citizens to have more negative views about China and the Chinese government.

Do information and perceptions about the outside world affect not only Chinese people's “voice” and “loyalty” but also their feelings about going abroad? Suggestive anecdotal evidence abounds. The recent story of a cyclist couple self-nicknamed “Gulu Sisi” is a case in point. The couple launched a global cycling tour covering the US, Europe, and Asia with only 50,000 RMB yuan (or about 8,000 US dollars) in bank deposits (Huang and Xiong Reference Huang and Xiong2015), partly because they thought that “except for airfare, basically everything else is a lot cheaper abroad than in China.”Footnote 2 Starting the tour in the US, however, they quickly discovered that “the China–US price comparison we have seen earlier is misleading. The US is actually quite expensive. Going to the supermarket by bus alone cost us 100 RMB yuan.”Footnote 3 As a result, they had to save on basic food and drink and sometimes even sleep on the street to reduce travel costs.Footnote 4

Such an incident should not come as a surprise. Most ordinary people in China do not have direct knowledge of life in Western countries; therefore, their perceptions of the outside world are generally based on second-hand information from the media and internet (Dong, Wang, and Dekker Reference Dong, Wang and Dekker2013).Footnote 5 Such information, however, is not always accurate. In fact, China's rapid social transformation in the reform era has led to “public sphere praetorianism” (Lynch Reference Lynch1999), with an abundance of diverse (mis)information flowing from a large variety of official and unofficial sources, including the country's clamorous internet (Huang Reference HuangForthcoming). A glance at Chinese media and internet will quickly reveal that they are full of popular but inaccurate or misleading tales about foreign countries, which often overly romanticize those countries (Bildner Reference Bildner2013; Darnton Reference Darnton2012; Neidhart Reference Neidhart2015; Yung Reference Yung2011). Consequently, a sizable share of the Chinese population may have an impression of foreign countries that is overly rosy. Indeed, earlier work has shown that they tend to be more critical than others are of China and the Chinese government, due to their implicit comparison of foreign and Chinese situations (Huang Reference Huang2015; Huang and Yeh Reference Huang and Yeh2016).

But despite the previous research on the relationship between international knowledge and domestic evaluations, no systematic study has been done about how (mis)information and (mis)perceptions about foreign countries affect citizens’ interest in leaving their own country, not just in China but in general. A large body of literature in international migration studies has focused on the issue of how socioeconomic opportunities and conditions in foreign countries shape emigration aspirations and decisions (Borjas Reference Borjas1987; Borjas and Bratsberg Reference Borjas and Bratsberg1996; Clark, Hatton, and Williamson Reference Clark, Hatton and Williamson2007; Docquier, Peri, and Ruyssen Reference Docquier, Peri and Ruyssen2014; Grogger and Hanson Reference Grogger and Hanson2011, Reference Grogger and Hanson2015; Hatton Reference Hatton2005; van Dalen, Groenewold, and Schoorl Reference van Dalen, Groenewold and Schoorl2005; Zaiceva and Zimmermann Reference Zaiceva and Zimmermann2008). But as Docquier et al. (Reference Docquier, Peri and Ruyssen2014) point out, existing studies almost always explain the decision to migrate “as a rational decision” (p. s38), and they assume that international differences in socioeconomic opportunities and conditions “are likely to be known to potential migrants and hence to affect their preferred destination” (p. s64).

A rare exception in this regard is Borjas and Bratsberg's (Reference Borjas and Bratsberg1996) well cited study of why many foreign-born immigrants to the US eventually leave the country, in which they conjecture that an important reason for the return migration is that many immigrants based their initial emigration decision on erroneous information about opportunities in the US. But, as the authors acknowledge in their study, their data ultimately do not allow them to distinguish this theory of return migration from an alternative theory that holds that these migrants had always planned to return after accumulating capital or wealth in the US. Some more recent studies have argued that emigration from developing countries to advanced nations often decreases the migrants’ trust in political institutions in the new country (Adman and Stromblad Reference Adman and Strömblad2011), and reduces their feelings of happiness despite improvement in material income (Stillman et al. Reference Stillman, Gibson, McKenzie and Rohorua2015), hinting that the migrants might have overestimated the socioeconomic opportunities or political institutions in foreign countries before migrating. But as these studies do not measure the migrants’ information and perception prior to migration, they cannot isolate the causal effect of (mis)information on emigration.

The previous literature on international migration and international knowledge, however, has yielded two important findings that are useful for generating hypotheses for this research: 1) emigration aspirations and decisions are significantly shaped by socioeconomic opportunities and condition in foreign countries; 2) citizens in a developing and authoritarian country are often misinformed about foreign countries, and correcting their overestimation of foreign socioeconomic conditions can influence their social attitudes. Based on these findings, it is natural to theorize that people with more positive perceptions of foreign countries will have stronger interest to live, study, or work abroad. This article's first main hypothesis (H1), then, is that individuals with more positive socioeconomic perceptions of foreign countries, in particular those who overestimate foreign socioeconomic conditions, have a higher inclination to go abroad. The second main hypothesis (H2) is that correcting one's socioeconomic overestimation of foreign countries will reduce inclination to go abroad, which would indicate that there is causal effect from rosier socioeconomic perceptions of foreign countries to higher interests in going abroad.

This article focuses on socioeconomic information and perceptions not only because previous studies in international migrations have demonstrated the central importance of economic aspirations in emigration decisions, as discussed above, but also because various scholars have argued that Chinese people's fascination with Western countries is more driven by perceptions about their economic prosperity, consumer products, science, and culture than about politics (Dong, Wang, and Dekker Reference Dong, Wang and Dekker2013; Shi, Lu, and Aldrich Reference Shi, Lu and Aldrich2011). But political knowledge about foreign countries may still be a factor affecting people's willingness to go abroad, and hence will be an important control variable in the following analysis, along with other control variables that will be discussed below. However, based on previous work on Chinese people's international knowledge, which has shown that their social attitudes are more shaped by perceptions of foreign socioeconomic conditions than by international political knowledge (Huang Reference Huang2015), I do not expect knowledge of foreign political affairs to significantly shape Chinese citizens’ inclinations to leave China.

Variables and Measurement

To test the above hypotheses I use data from an online survey experiment conducted in October 2014 and a college survey conducted in June 2011. The online survey experiment can isolate the causal effect of the respondents’ information and perceptions, and is thus the main focus of the article, while the college survey provides additional evidence from a different sample. In both studies the respondents were asked the following question: “Suppose you have such an opportunity, are you interested in going abroad for study, work, or simply emigrating to another country?” The response to this question is the dependent variable of the studies, and the choices were (1) not interested; (2) interested in going abroad for study or work for some time, but not emigration; (3) somewhat interested in emigrating abroad; (4) strongly interested in emigrating abroad. Given the increasing interest in going abroad, these answers will be respectively coded as 1, 2, 3, and 4.Footnote 6 Note that the question started with “[s]uppose you have such an opportunity”; therefore, the respondents’ answers would reflect their interest in going abroad rather than financial or other constraints to actually doing so.

Following Huang (Reference Huang2015), the surveys measured the respondents’ socioeconomic information and their perceptions of the outside world, the main independent variable, by asking them to estimate the performance of countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, hereafter referred to as the West), particularly the US, on eight important indicators of socioeconomic development: per-capita personal income, unemployment rate, life expectancy, income inequality, years of schooling, home ownership, air and water pollution, and homicide rate. The emphasis was on the US because it is the country that most captures Chinese people's imagination about the outside world and often the default country against which they compare China's performance. Even though there is no standard formula to choose socioeconomic topics for the questions, all the eight socioeconomic questions were about issues with great salience in China, and could thus largely represent the perceptions of Chinese citizens about what life in the West is like.

While the social scientific literature has extensively studied citizen knowledge and information, the previous literature is predominantly about political knowledge, particularly domestic political knowledge (e.g., Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Lupia and McCubbins Reference Lupia and McCubbins1998; Prior Reference Prior2007). The measurement of foreign socioeconomic information in this research therefore demands some explanation. Most importantly, measuring political knowledge usually just means checking whether a respondent correctly answered a factual question about some political institution, players, or processes. The nature of the socioeconomic questions here, however, is such that their answers could be ordered by how favorably they portrayed Western socioeconomic conditions. For instance, one of the foreign socioeconomic questions in the 2014 survey experiment asked which of the following numbers was closest to the annual per-capita personal income in the United States: (a) 21,000 USD, (b) 44,000 USD, (c) 67,000 USD, or (d) 90,000 USD. The correct answer, according to US official statistics, was (b) (US Bureau of Economic Analysis 2014). All the other answers were wrong but in different ways. Answer (a) underestimated the US income level, (c) overestimated it, and (d) overestimated it to a higher degree. Another socioeconomic question asked about the average life expectancy in OECD countries: (a) 72.1, (b) 76.1, (c) 80.1, or (d) 84.1. The correct answer was (c) (OECD 2014); both answers (a) and (b) underestimated OECD countries’ average life expectancy, to different degrees, while (d) overestimated it.Footnote 7

As shown in these two examples, for each foreign socioeconomic question the surveys provided four choices, with the differences between the neighboring choices reasonably large, while ensuring that all choices were at least somewhat plausible. To avoid the possibility that the respondents could only err in one particular direction, the correct answers to all the socioeconomic information questions were put as either (b) or (c), the two “moderate” choices. In addition, because half of the questions had the second best numbers as the correct answers, while the other half had the second worst numbers, the respondents had equal chances for overestimation and underestimation. To construct the respondents’ socioeconomic perception scores, each correct answer was given a score of zero, while the choice next to the correct answer that overestimated the West was given a score of 1, and the choice that overestimated the West even more was given a score of 2. Answers that underestimated the West were similarly given a score of –1 or –2. A respondent's aggregate foreign socioeconomic perception score was then summed over all eight questions. A score of zero would mean that a respondent's perception of foreign socioeconomic conditions was very balanced on average, while a positive (negative) score indicated that, overall, her estimate was better (worse) than the reality.Footnote 8

Besides the aggregate socioeconomic perception scores, in the following analysis the respondents are also divided into three groups: 1) those who had systematic underestimates of Western conditions, 2) those who had roughly balanced estimates, and 3) those who had systematic overestimates. I categorize socioeconomic scores higher than or equal to 3 as systematic overestimates, scores lower than or equal to –3 as systematic underestimates, and the rest as approximately balanced estimates. The threshold was set at 3 because it represented one standard deviation in the distributions of the socioeconomic perceptions scores in the surveys.

The online survey experiment and the college survey had the same topics for the socioeconomic information questions, while the answers for some questions were somewhat different since the world's socioeconomic conditions did not stay constant over the three years between the surveys. To give the students some bases for judgment (since some of the questions asked about somewhat abstract issues, e.g., income inequality), relevant statistics for China were provided in many of the socioeconomic questions in the college survey. The online survey experiment removed such reference information about China in the socioeconomic questions to make sure the respondents’ answers were not primed by information about China. Results from the two studies were consistent, boosting confidence in the robustness of the findings under alternative questionnaire designs.

The surveys also measured the respondents’ foreign political knowledge by asking them a series of factual questions about political figures and recent events around the world. The main study in 2014 thus included questions on the Scottish independence referendum, the 2013 US federal government shutdown, the political crisis in Thailand, Edward Snowden's revelation of NSA surveillance programs, the Syrian civil war, and political figures, such as the French president, the Pope, and Nelson Mandela. The 2011 college survey included questions on the 2010 US midterm election, the health care reform of the Obama administration, the death of Bin Laden, the Arab Spring, the European sovereign debt issue, and the identities of several international political figures, including the British Prime Minister and the Venezuelan President. There is no standard way to formulate a set of representative questions to measure international political knowledge, but since the 10 questions in each survey covered diverse issues and regions, they constituted a reasonable set of questions to test the respondents’ foreign political knowledge. Following the standard practice in studies of political knowledge, I calculated the respondents’ political knowledge scores as the number of questions to which they gave correct answers.

The surveys also included a series of questions that would serve as control variables in the analysis. To control for political factors beyond political knowledge that might affect people's interest in going abroad, the respondents were asked about their political interest, internal political efficacy, and external political efficacy. Internal political efficacy refers to the belief that one can understand politics and political issues, and external political efficacy refers to the belief that one can effectively participate in politics and that the government will respond to one's demands. These variables may be related to interest in going abroad because people with higher internal efficacy (as well as political interest) may be more aware of the deficiencies of China's political system and, hence, more interested in moving abroad. On the other hand, people with higher external efficacy are more confident that they can affect government decisions and help make China a better country; thus, foreign lands would be less attractive.

In addition, the surveys asked about the respondents’ national pride, individualism, news consumption, and general life satisfaction. National pride has obvious potential effects on one's inclination to leave the country. Individualism was asked because Western countries are often admired in China for their individualism, while China is traditionally regarded as a collectivist society. Thus, a higher level of individualism may increase one's interest in leaving the country to pursue individual happiness. Since the research examines how information affects one's inclination to go abroad, it was natural to include level of consumption of mainstream news in the surveys. Lastly, because general life satisfaction may also affect one's desire to leave her country to pursue a different life, it was included in the surveys as well. The wordings of these sociopolitical predisposition questions can be found in the Online Appendix to this article. Sociodemographic questions included gender, family income, and membership in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Education and age were also asked in the 2014 online survey experiment but not the 2011 college survey, since the respondents in that survey were all sophomores, as explained below.

A concern readers may have about this research is that it uses online and student samples rather than nationally representative samples. The main reason for the sample selection is that this is the first direct study about the effects of international knowledge and perception on Chinese citizens’ interest in going abroad. No existing dataset with nationally representative samples contains questions directly measuring the respondents’ international socioeconomic perceptions that can be used for this research. Moreover, the sociodemographic profile of the online sample was quite close to the general Chinese internet population along multiple key dimensions, as discussed below, and the university surveyed for the article is a typical Chinese university. The anonymous nature of the surveys with the online and student samples also provided a more relaxed environment for the respondents to reveal their candid attitudes than the face-to-face interviews typically employed in nationally representative surveys. Although my respondents were somewhat younger and better educated, on average, than the Chinese population in general, the young and better educated generations are also more physically mobile (thus the main potential force for emigration), as well as politically and economically active, and hence worth particular attention. It should be stressed that this research is primarily interested in factors shaping individuals’ interest in leaving China, which should affect the general population, rather than the specific percentages of the Chinese public interested in going aboard, which may vary across sub-populations. Nevertheless, citizens of older generations may have more firmly established lifestyles and their interest about moving abroad may be less swayed by new information about foreign countries. Findings from this research, therefore, may be most relevant for the younger and more mobile sub-populations.

MAIN STUDY: ONLINE SURVEY EXPERIMENT

Recruitment and Survey Experimental Design

The subjects of the October 2014 online survey experiment were recruited from a popular Chinese crowd-sourcing website (similar to Amazon.com's Mechanical Turk), and then directed to a US-based website where they took the survey anonymously. Each unique IP address and each unique account at the recruiting platform was allowed only once in the study to prevent repetitive participation. Using crowd-sourcing platforms to recruit subjects has become common in social science research, and its validity has been demonstrated in a series of studies (e.g., Berinsky, Huber, and Lenz Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Buhrmester, Kwang, and Gosling Reference Buhrmester, Kwang and Gosling2011). The Chinese crowd-sourcing platform has also been used in previous experimental studies of Chinese public opinion (Huang Reference Huang2015, forthcoming).

As shown in the Online Appendix, participants in the survey experiment came from all walks of life and various age and educational groups. They were also geographically distributed throughout China. In fact, the regional, occupational, and gender distributions of the participants were roughly similar to those of the Chinese internet population around the time of the survey. About a quarter of the subjects were students, and other occupations included corporate employees, professionals, workers, government employees, farmers, the self-employed, and the unemployed. The sample thus had broad social representation.

In the survey experiment the subjects were randomly divided into a control group and a treatment group in a between-subjects design. All subjects were first asked about their general sociopolitical predispositions including political efficacy, national pride, and individualism. Next, they were asked about their perceptions of foreign socioeconomic conditions. Then, after all socioeconomic questions had been answered, those in the treatment group were told the correct answers to the questions that they had answered wrong, while those in the control group did not receive any correction. Afterwards, all subjects were asked about their interest in going abroad (the dependent variable), followed by political knowledge questions about foreign countries and finally demographic questions.

A challenge with online surveys is ensuring that respondents pay sufficient attention to questions; therefore, I dropped from the analysis a small number of participants who finished the survey faster than a pre-determined threshold.Footnote 9 In the end, the survey experiment had 988 effective participants, with 479 in the control group and 509 in the treatment (correction) group.

RESULTS

Results on the relationship between information about foreign countries and interest in going abroad are shown in Table 1. Given the ordinal and categorical nature of the dependent variable, I analyze the data with ordered logit regressions. Model (1) is the basic specification, including only the main variables of interest (socioeconomic perception and political knowledge), demographic information, and whether a respondent was in the control or correction group as the independent variables. As (1) clearly shows, respondents with more positive perceptions about foreign socioeconomic conditions are more interested in going abroad. International political knowledge, on the other hand, does not have a significant relationship with one's interest in going abroad.

Table 1 Socioeconomic Perception, Political Knowledge, and Interest in Going Abroad (Online Survey Experiment)

Results from ordered logit regressions; standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

Model (2) in Table 1 adds additional political variables to control for political factors beyond political knowledge that may influence a person's exit intentions: political interest, internal political efficacy, and external political efficacy. The results for socioeconomic perception and international political knowledge remain unchanged from the basic model (1). The full model (3) adds other variables that may affect one's interesting in going abroad: national pride, individualism, news consumption, and life satisfaction.

As Table 1 shows, across these different specifications, socioeconomic perceptions of foreign countries are consistently and positively related to one's inclination to go abroad. H1 is thus strongly confirmed. As I expected, political knowledge of foreign countries, on the other hand, is not significantly related to one's exit intentions. This suggests that Chinese citizens’ inclination to go abroad is more about socioeconomic aspirations than political considerations. One may also note that the cut points are almost always significant, particularly cut point 3, which suggests the ordered logit regression with four categories is an appropriate choice.

With regards to the control variables, education consistently increased the respondents’ interest in going abroad, perhaps because of the (perceived) better opportunity for success abroad that a higher education could provide. Income did not have a consistent effect, but sometimes reduced one's interest in going abroad, perhaps because a decent job and life at home reduces the attraction of foreign lands. It is also interesting that CCP membership did not have any significant relationship with one's interest in going abroad, likely because in contemporary China, party membership is often of instrumental value rather than reflective of a person's ideological or political views (Dickson Reference Dickson2014). Unsurprisingly, national pride reduced the inclination to go abroad, while individualism increased the incentive to pursue individual happiness in a foreign land.

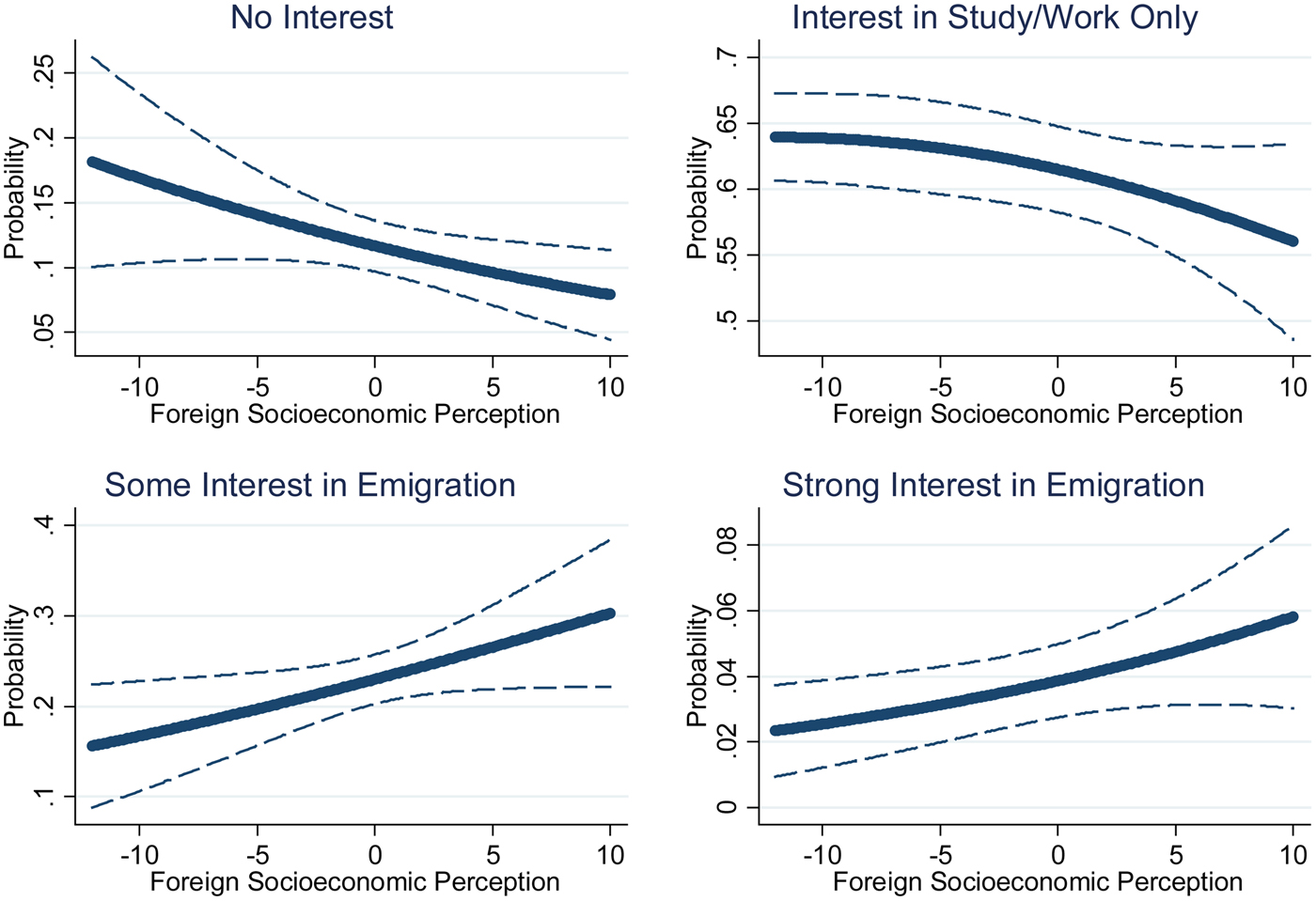

To make the relationship between one's interest in going abroad and perceptions about foreign socioeconomic conditions substantively clearer, Figure 1 plots the respondents’ predicted interest in going abroad as a function of their foreign socioeconomic perceptions, based on the full specification (3), with the covariates fixed at mean values. As a respondent's foreign socioeconomic perception increased from the lowest level in the sample to the highest, her probability of having no interest in going abroad decreased from 0.18 to 0.08. The probability of being interested in emigrating abroad, on the other hand, increased significantly: The probability of being somewhat interested in emigration increased from 0.15 to 0.30, and that of being strongly interested increased from 0.02 to 0.06. The probability of having interest in study or work only decreased to some extent (from 0.64 to 0.56), because those who had high positive socioeconomic perceptions of foreign countries were really interested in emigration rather than temporary study or work abroad.

Figure 1 Predicted Interest in Going Abroad (Online Respondents)

Next, I turn to examining H2: the effect of correcting misinformation about foreign socioeconomic conditions. Table 2 shows the average treatment effects of correcting misinformation. Since the effect of correction will obviously depend on whether an individual's misinformation resulted in overestimating or underestimating foreign countries, the Table reports the effects separately according to whether the respondents overestimated, underestimated, or had roughly balanced perceptions of foreign countries.

Table 2 Group Means and Average Correction Effects on Interest in Going Abroad (Online Survey Experiment)

T-tests with unequal variances. The first two rows are group mean estimates, with sample standard deviations reported in the parentheses. The third row are mean difference estimates, with standard errors reported in the parentheses. The P-values reflect one-sided hypothesis tests. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

As the t-tests in Table 2 show, correcting overestimation of foreign conditions significantly reduced the respondents’ interest in going abroad. On the other hand, the effects of correcting the misinformation of the respondents who underestimated or had roughly balanced perceptions of foreign socioeconomic conditions were close to zero.

To corroborate the results from the t-tests, I also ran ordered logit regressions with the same control variables as in Table 1, and the results are reported in Table 3. Because the effects of correction depend on whether one overestimated or underestimated foreign countries, correction is interacted with overestimation and underestimation, and socioeconomic perception is represented by overestimation and underestimation. As Table 3 shows, overestimation of foreign socioeconomic conditions was significantly correlated with the respondents’ interest in going abroad, while underestimation was not. This suggests that the relationship between perceptions of foreign socioeconomic conditions and interest in leaving China is mainly driven by overestimation of foreign socioeconomic conditions rather than underestimation.

Table 3 Effects of Overestimation and Correction (Online Survey Experiment)

Results from ordered logit regressions; standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

More importantly, the consistently significant and negative coefficients for the interaction of overestimation and correction in Table 3 show that correcting the misinformation of those respondents who overestimated foreign socioeconomic conditions reduced their inclination to leave China, even after controlling for a set of other variables. H2 is thus strongly confirmed. Since underestimation had no significant relationship with interest in going abroad, correcting such misinformation had no significant effect on changing one's exit intentions.

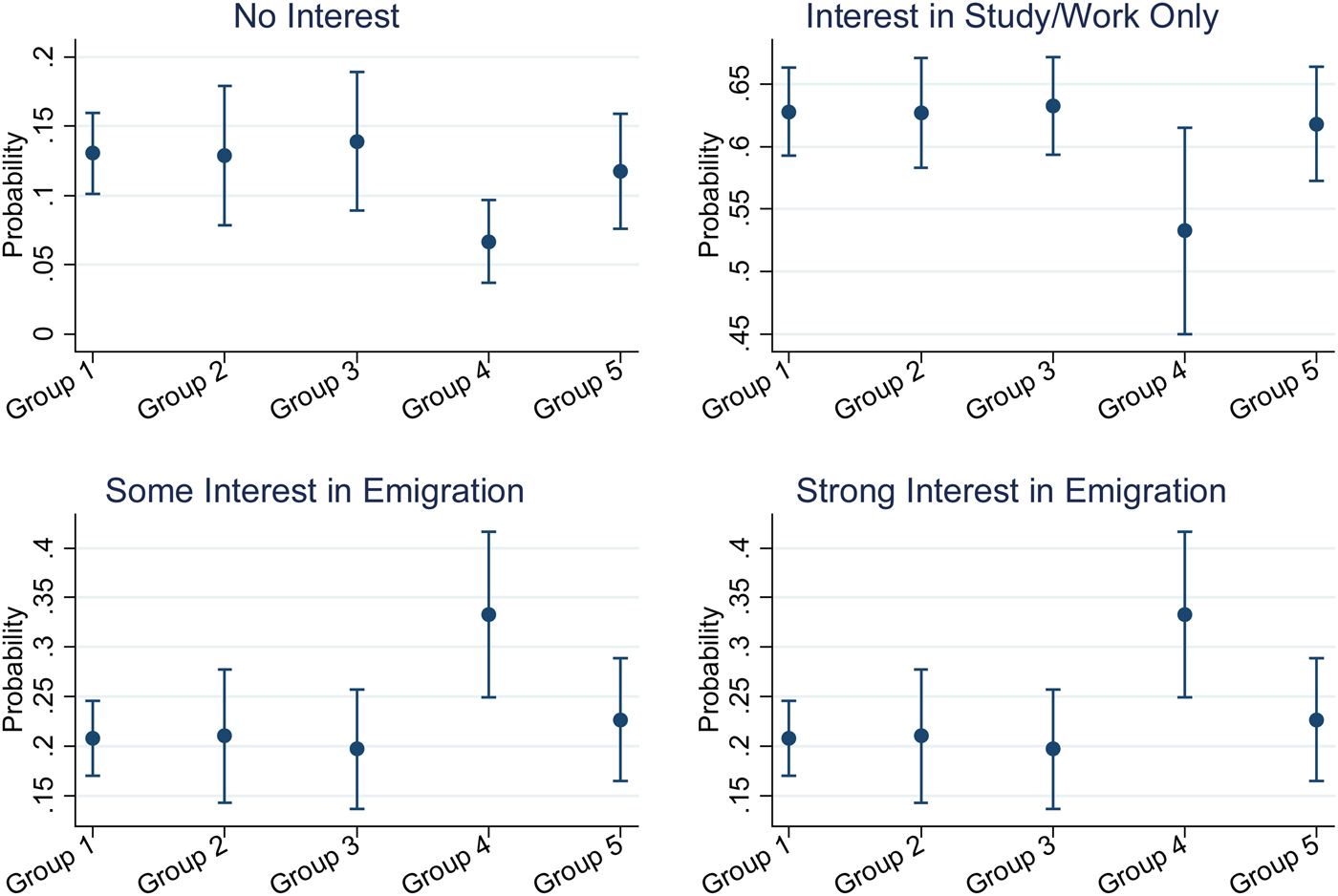

To more clearly show the effects of overestimation and, especially, correction of misinformation, it is useful to compare different groups of respondents according to whether they systematically misestimated foreign socioeconomic conditions and whether they received correction. In Figure 2, Group 1 were baseline respondents who had roughly balanced estimates of the West and did not receive any correction; Group 2 were respondents who underestimated the West but did not receive correction; Group 3 were respondents who underestimated the West and then received correction; Group 4 were respondents who overestimated the West but did not receive correction; Group 5 were respondents who overestimated the West and then received correction.

Figure 2 Effects of Overestimation and Correction (Online Respondents)

As Figure 2 shows, Groups 1–3 had similar levels of probabilities in all four potential choices: no interest, interest in temporarily studying or working abroad, some interest in emigration, and strong interest in emigration. Group 4 (the overestimating respondents), however, were significantly less likely to have no interest in going abroad (or have interest in temporarily studying or working abroad only) than the first three groups. They were significantly more likely to have either some or strong interest in emigrating abroad. Most importantly, the probabilities of Group 5, the initially overestimating respondents who received correction, in the four potential choices returned to the levels of the baseline group. In other words, while overestimating foreign socioeconomic conditions significantly increased the respondents’ interest in leaving China, correcting the misinformation led their interest to return to a more “normal” level.

These results from a diverse internet sample not only show that the positive relationship between perceptions of foreign socioeconomic conditions and interest in going abroad is quite robust, but, more importantly, that the relationship is not just a correlation. Instead, there is a causal effect from more positive perceptions of foreign conditions to higher interest in leaving China, since correcting overestimations reduced the respondents’ interest in emigration. Thus, both of the main hypotheses are confirmed.

ADDITIONAL EVIDENCE: COLLEGE SURVEY

To further validate the relationship between international knowledge and interest in going abroad, in this section I report results from a college survey conducted in eastern China in June 2011 with about 1,200 sophomores attending a university-wide required course. The university is mid-sized and mid–upper ranked, which made the respondents potentially more representative of average college students in China than students from elite universities, who are often the targets of academic surveys. The anonymous survey was a class activity conducted in one out of two sections, thereby covering all but a few small majors at the main campus of the university. The completion rate was quite high, as students found the questionnaire very “refreshing” and “interesting.”

The questionnaire in the college survey was similar to that in the online survey experiment. However, because there was no correction procedure, the dependent variable in the college survey was asked before questions about foreign socioeconomic conditions and political knowledge, in order to avoid these knowledge and perception questions from priming the students’ answers about going abroad. The summary statistics of the survey can be found in the Online Appendix.

Given the ordinal and categorical nature of the dependent variable, I again analyze the data with ordered logit regressions. The results are reported in Tables 4 and 5, which respectively use the respondents’ raw socioeconomic perceptions scores and whether they overestimated/underestimated foreign conditions to represent their socioeconomic perceptions, as in Tables 1 and 3. Since the survey did not have a correction component, the analysis here will not produce any treatment effects.

Table 4 Socioeconomic Perception, Political Knowledge, and Interest in Going Abroad (College Survey)

Results from ordered logit regressions; standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

Table 5 Effect of Overestimation and Underestimation (College Survey)

Results from ordered logit regressions; standard errors in parentheses. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05

As expected, Table 4 shows that more positive perceptions of foreign socioeconomic conditions were significantly correlated with higher interest in going abroad across all three different specifications. Political knowledge was correlated with a stronger desire of the students to go abroad in models (1) and (2), but this relationship loses statistical significance at the 0.05 level in the full specification (3), with more control variables, particularly national pride and individualism, included. Similarly, Table 5 shows that overestimation consistently increased the students’ interest in leaving China. Underestimation exhibited a negative effect in models (1) and (2), but the relationship loses statistical significance in the full specification (3).

With regards to the control variables, female students were more interested in going abroad, but the gender effect did not exist in the online survey. Income increased the students’ interest in going abroad, which is different from the online respondents, perhaps because the students were not labor market participants and their family wealth made them more willing to go abroad.Footnote 10 CCP membership again had no effect, consistent with its instrumental value. The effects of national pride and individualism were also the same in the college survey as in the online survey experiment: The former reduced interest in going abroad, while the latter increased it. Examining both the online experiment and college survey, internal political efficacy increased while external political efficacy decreased inclinations to leave China, although the effect was not consistent across the board. Political interest, on the other hand, generally had no effect (or a negative effect) on one's interest in leaving China. But the general effect of political efficacy is reasonable: understanding China's political issues (internal efficacy) may make one more aware of the deficiency of China's political system, which leads to a higher incentive to go abroad. A sense of being able to influence government decisions (and hence help change the country), on the other hand, naturally makes it more worthwhile to stay in China. The former result about internal political efficacy shows that one's interest in going abroad is not politics-free. At the same time, the latter result about external efficacy further corroborates the article's results, since it shows that the belief that one can help make the country better and reduce the Sino-foreign gap can reduce one's interest in going abroad.

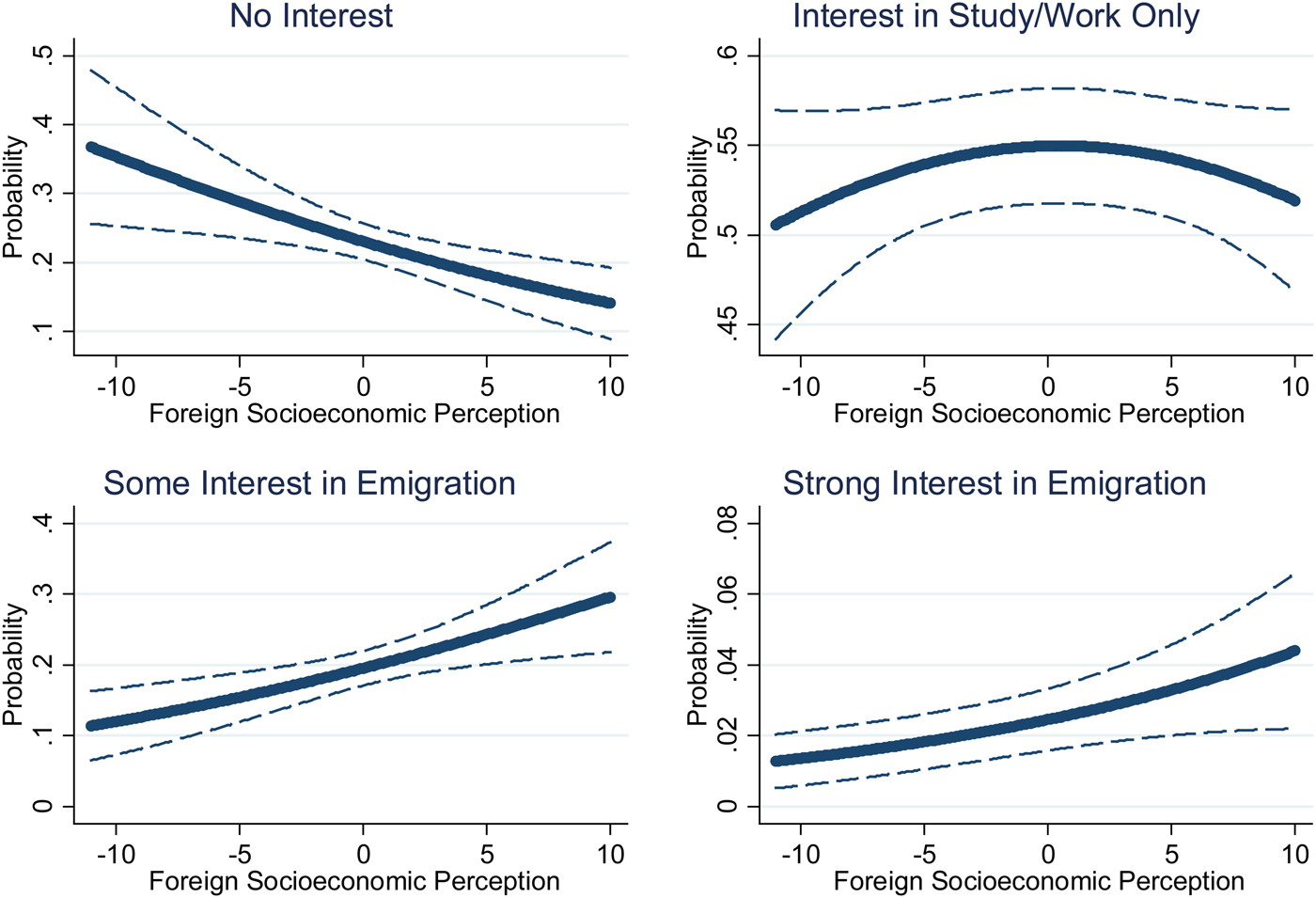

Again to make the relationship between socioeconomic perception of foreign countries and interest in going abroad substantively clearer, Figure 3 shows the students’ predicted interest in going abroad as a function of their foreign socioeconomic perception scores, based on the full specification in Table 4, with the covariates fixed at mean values. As a student's foreign socioeconomic perception score increased from the lowest in the sample to the highest, her probability of having no interest in going abroad decreased from 0.37 to 0.14, and the probability of having interest in temporarily studying or working abroad without emigration remained largely unchanged (from 0.51 to 0.52).Footnote 11 The probability of being interested in emigrating abroad, on the other hand, had a significant increase: the probability of being somewhat interested in emigration increased from 0.11 to 0.30, while that of being strongly interested in emigration increased from 0.013 to 0.044. Clearly, having more positive socioeconomic perceptions about foreign countries significantly increased the respondents’ inclinations to leave China.

Figure 3 Predicted Interest in Going Abroad (College Respondents)

The general pattern exhibited in the 2011 college sample was thus consistent with the 2014 online sample, despite their notable differences in time and respondents, which indicates the robustness of the findings. In other words, the relationship between socioeconomic perception of foreign countries and interest in going abroad does not appear to be restricted to any particular sample, but holds quite broadly.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Chinese citizens, including middle-class professionals, students, and the wealthy class, are flocking abroad in unprecedented numbers. Existing academic studies about Chinese migration, however, tend to focus on the emigration of scientific and technological talents and strategies to encourage their return (the so-called “brain drain” or “brain circulation” issue, discussed by Saxenian Reference Saxenian2005; Zweig, Fung, and Han Reference Zweig, Fung and Han2008; Zweig and Wang Reference Zweig and Wang2013), (elite) overseas returnees’ social influence or international outlook, and Chinese people's opinion of them (Li Reference Li2010; Han and Zweig Reference Han and Zweig2010; Tai and Truex Reference Tai and Truex2015). The rapid rising tide of Chinese going abroad in the twenty-first century, however, is no longer restricted to technological or intellectual elites; it is a mass phenomenon. What motivates people to go abroad, rather than the issue of what will happen if/when they return, is also a first order question in our understanding of this far-reaching social trend. Yet there has been a dearth of studies about one of the most important social trends in the most populous country in the world.

This research shows that Chinese citizens with more positive perceptions, and especially overestimation, of foreign socioeconomic conditions, are more inclined to go abroad, and the relationship contains a causal effect, not just correlation. On the other hand, international political knowledge (as measured by knowledge of political affairs and political figures in foreign countries) does not have a significant or consistent effect on one's inclination to go abroad. These results suggest that Chinese citizens’ motivations for moving abroad are more socioeconomic than political, and the current trend of Chinese people flocking abroad does not always represent informed decisions to vote with their feet, as is often assumed by the conventional wisdom.

An inclination to go abroad is not the same as actually going abroad, since those with interest in leaving China may not do so due to financial constraints or family obligations. But one develops an inclination to go abroad first, before actually going abroad, and those with financial or other constraints today may not have those constraints tomorrow. Moreover, people who want to go abroad but are “stuck” in China for various reasons are likely to develop dissatisfaction or even resentment of the society, which will have social and perhaps political implications. For these reasons, it is critical to study people's inclination to leave China, not just their actual behavior.

A likely concern about this research's findings is potential reverse causality: People with higher inclination to leave China may be motivated to pay more attention to positive stories about foreign countries while ignoring negative information, and this selective learning can lead to overly rosy perceptions of the situations abroad. The online survey experiment, however, was designed to address this causality issue. A necessary and sufficient condition that there is a causal effect from overly positive perceptions of foreign countries to higher interest in going abroad is that correcting the misperceptions will reduce such interest. If there is no such causal effect, or if the causal direction is instead purely from interest in going abroad to (mis)perceptions of foreign countries, correcting the misinformation will not change one's interest in going abroad. In fact, people with motivated reasoning may even strengthen their predispositions after encountering discordant information (Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006). The result of the survey experiment clearly indicated that providing more accurate information to the respondents who initially overestimated Western socioeconomic conditions reduced their interest in emigration. Therefore, there is a causal effect from more positive perceptions and over-estimation of foreign socioeconomic conditions to higher interest in leaving China.

Some previous studies have shown that the Chinese public often have negative political opinions about some foreign powers, especially their behavior in world affairs and policies toward China (e.g., Weiss Reference Weiss2014). This is not at odds with this article's finding that some Chinese citizens have overly rosy perceptions of Western countries’ domestic socioeconomic conditions. As has been pointed out, the Chinese public often have bifurcated images of Western countries, admiring their domestic socioeconomic and other achievements while criticizing their international behavior or policies toward China (e.g., Shi, Lu, and Aldrich Reference Shi, Lu and Aldrich2011). Naturally, ordinary people's intentions about moving abroad are more shaped by perceptions of what life in other countries is like than their foreign policies.

Given this research's findings, one may wonder what would happen if the media and/or government start to portray foreign countries more negatively. Media programs and internet posts that describe foreign countries in an overly negative light also exist in China, but they are less popular and less believed, as numerous jokes about the prime time news program of China's national TV network, Xinwen Lianbo, indicate (Huang and Yeh Reference Huang and Yeh2016). The recent “Zhou Xiaoping” incident provides another example. Zhou, a previously obscure blogger who had written some essays portraying life in the US in an overly bleak picture, shot to fame after being publicly praised by President Xi Jinping in a high-level government meeting (Los Angeles Times 2014). But he and his writings were then so ridiculed by China's internet users that the government deleted his name from the final published minutes of the meeting.

More generally, as Huang (Reference Huang2015) has argued, when a formerly closed society opens itself, citizens start to doubt their own countries’ media and acquire some limited information about the outside world, which may include overly romantic perceptions of foreign countries. Under such circumstances, allowing citizens to gain access to foreign media, which carry more realistic reports about foreign countries’ socioeconomic conditions, may actually help dilute the influence of overly rosy internet posts about foreign countries that are popularly circulated in China (Huang and Yeh Reference Huang and Yeh2016). The problem, of course, is that foreign media also carry political news that is often unfavorable to the Chinese government (the recent Panama Papers news is a case in point). Therefore, it faces a conundrum: opening foreign media may provide citizens with more accurate information about foreign socioeconomic conditions, but it may also bring in negative political information that threatens the government's rule.

Although it seems natural that more positive perceptions, and especially overestimation of foreign conditions, will lead to higher interest in going abroad, I am not aware of any previous research that has explicitly established this causal relationship. This research demonstrates that going abroad is not only a function of people's desires and preferences but also of their information and perception of the outside world. Theoretically, the results of the article prove Borjas and Bratsberg's (Reference Borjas and Bratsberg1996) conjecture that erroneous information about opportunities in a foreign country affects many people's emigration decisions, at least for the Chinese case. The results are also consistent with some recent migration studies of other countries that show emigration often does not live up to the migrants’ high expectations (Adman and Stromblad Reference Adman and Strömblad2011; Stillman et al. Reference Stillman, Gibson, McKenzie and Rohorua2015). Practically, the findings mean that the current increasing trend of Chinese people moving abroad does not necessarily reflect voting with the feet, and it may change as people acquire fuller and more accurate information, sometimes through living abroad. This is perhaps one of the reasons behind the phenomenon of returning to China from overseas (“haigui”), which has become increasingly significant in recent years.

This article aims to motivate further research on the relationship between people's information and perception of foreign countries and their inclination to go abroad. In particular, future research can expand the investigation of the effect of political information on people's interest in going abroad. While this article has included knowledge of foreign/international politics in the analysis, political knowledge is certainly more than familiarity with political events and leaders. Given that China is the largest authoritarian country in the world, future research should explicitly examine how information and perceptions about practices of democracy and rule of law abroad, or China's deficiencies in political rights and civil liberties as compared to advanced democracies, affect people's inclinations to go abroad.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2016.44.