Introduction

Populism has risen sharply as a global political phenomenon in recent decades (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2021; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017). Despite an extensive body of research, there remains a significant need for comparative studies to explore how populism emerges and evolves across diverse democratic contexts. While considerable effort has been dedicated to understanding populism within advanced Western democracies (e.g., Taggart Reference Taggart2004, Reference Taggart, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2018), existing knowledge remains incomplete regarding its varied forms in newer democracies, where pluralistic norms have not yet been fully consolidated. Indeed, this gap is critical because the manifestations of populism in these third-wave democracies, countries transitioning from authoritarian rule to democracy since the mid-1970s (Huntington Reference Huntington1991), can differ markedly from those observed in established democracies. Hence, it is essential to ask whether existing conceptualizations of populism adequately capture its diverse expressions, particularly in political environments where democratic norms remain fragile and unstable.

The context-dependent nature of populism (e.g., Marcos-Marne, Llamazares, and Shikano Reference Marcos-Marne, Llamazares and Shikano2022; Cranmer Reference Cranmer2011; Jung Reference Jung2025) poses significant challenges in grasping its varied manifestations across different political environments. Specifically, while existing scholarship provides a robust framework for understanding populism’s general characteristics, it is less clear whether these concepts fully encompass its distinctive expressions in third-wave democracies, where democratic consolidation remains fragile. In such democracies, populism is likely to take sectarian characteristics, defined by pronounced partisan hostility, moralistic denunciation of political opponents, and intensified societal polarization. Given that these democratic settings often lack stable pluralistic traditions, sectarian populist rhetoric can thrive by exploiting deeply embedded political divisions and weak institutional constraints. Therefore, closely examining the unique patterns of sectarian populism in third-wave democracies is essential for accurately assessing its implications for democratic stability and effective governance. This article addresses precisely this concern by examining the specific manifestations and dynamics of populism in South Korea, a representative third-wave democracy with a relatively brief history of democratic governance and an evolving political landscape still grappling with the complexities of pluralism. While South Korea has formally transitioned to democracy, the political environment remains characterized by intense partisanship, sharp polarization, and frequent confrontations between rival political factions (Han Reference Han2021; Lee Reference Lee2015). These conditions potentially foster anti-pluralistic sentiments and render South Korea particularly susceptible to sectarian populism. Recognizing this, the present study aims to contribute to our understanding of how populist rhetoric, particularly in its sectarian form, is strategically deployed within mainstream political parties in such a democracy.

To accomplish this, the article systematically analyzes the political rhetoric of South Korea’s two dominant mainstream parties, the Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) and the People Power Party (PPP), over a decade, from 2012 to 2022. Utilizing a dataset of 52,487 official party statements from both mainstream parties, this research leverages advanced large language models (LLMs) to classify and evaluate populist content. Specifically, each document was scored on a continuous populism scale and further categorized according to different populist subtypes, enabling the capture of subtle but important distinctions in populist discourse. This nuanced analytical strategy facilitates a deeper understanding of populism’s diverse manifestations, especially those more subtle or ambiguous forms that traditional classification methods might overlook.

The analysis reveals several notable patterns. Firstly, populist rhetoric across both major parties has exhibited a clear upward trajectory over the studied decade, indicating a growing mainstream acceptance and strategic reliance on populist discourse. Importantly, while the specific timing and intensity varied slightly, both parties intensified populist rhetoric significantly during election periods, underscoring the instrumental use of populist appeals as a tool to mobilize voter support. Furthermore, the status of a party as either in government or opposition was a key factor influencing the frequency and intensity of populist language; notably, populist rhetoric escalated dramatically when parties found themselves relegated to opposition, highlighting populism’s role as a political strategy to critique incumbents and rally discontent.

What emerged as the overwhelmingly dominant form of populist rhetoric in South Korea was a variant referred to as sectarian populism, characterized by moralization, hostility toward political opponents, and stark divisions between political factions. Unlike European democracies where populist discourse frequently revolves around immigration (Greven Reference Greven2016; Grande et al. Reference Grande, Schwarzbözl and Fatke2019; McKeever Reference McKeever2020) or Latin American contexts emphasizing economic inequality (Edwards Reference Edwards2010; Leon Reference Leon2014), sectarian populism in South Korea primarily centered around intense political and moral conflicts. Both the DPK and the PPP extensively employed sectarian rhetoric, often accusing each other of corruption, undermining democratic values, or betraying national interests. This type of populism not only amplified existing polarization but also risked eroding pluralistic democratic norms by entrenching political rivalries in moralistic, uncompromising terms.

The findings from this systematic examination carry significant theoretical and empirical implications. First, the consistent rise and strategic employment of sectarian populism in South Korea underscores how mainstream parties in countries with relatively recent democratization and weak pluralistic traditions increasingly rely on anti-pluralistic rhetoric to compete electorally. This reliance reveals inherent vulnerabilities in democratic consolidation processes, where populist strategies not only polarize political competition but also risk weakening essential democratic norms, such as mutual tolerance and respect for diverse viewpoints. Second, the identification of sectarian populism as the dominant form challenges the conventional binary of left- and right-wing populism common in Western literature, highlighting how populism in third-wave democracies might cut across ideological lines and become embedded as a core strategy of political mobilization and survival.

The paper is structured as follows: it begins by reviewing the theoretical relationship between populism, democracy, and anti-pluralism, followed by a detailed discussion of the methodological approach employed. Subsequently, the empirical findings are presented, highlighting critical patterns in the evolution of populist rhetoric and its sectarian form in South Korea. Finally, the discussion explores the broader implications of these results for democratic stability, pluralistic political discourse, and future research directions on populism in third-wave democracies.

Populism, democracy, and anti-pluralism

As populism has gained global prominence, scholarly efforts to define and understand it have proliferated, leading to diverse conceptualizations. It has been conceptualized as a political strategy (Weyland Reference Weyland2001), a discursive style (Betz, Reference Betz1994; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010; Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007; Abts and Rummens Reference Abts and Rummens2007), a political style (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016), and an organizational form centered on charismatic leadership (Taggart Reference Taggart1995, Reference Taggart2000; Tarchi Reference Tarchi2002). In addition, the ideational approach frames populism as an ideology that divides society into two antagonistic groups: “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite” (Mudde Reference Mudde2004, p. 543; Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017, p. 5). Despite these diverse perspectives, a unifying feature of populism is its inherent exclusivity, reinforcing a binary opposition between the people and the elite (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Mudde and Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2017; Abts and Rummens Reference Abts and Rummens2007; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010; Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016; Taggart Reference Taggart1995). This paper synthesizes these conceptualizations and defines populism as a political phenomenon characterized by a Manichaean worldview, people-centrism, anti-elitism, and authoritarian rhetoric (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2009; Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Carlin, Littvay and Kaltwasser2018). These elements construct politics as a moral struggle between a virtuous “true people” and a corrupt elite, fundamentally opposing pluralist principles of negotiation and diversity.

Building on the inherent exclusivity of populism, its anti-pluralistic nature becomes particularly evident in its rejection of diverse opinions and interests essential to democratic pluralism. Populism’s binary division of society into true people versus the corrupt elite challenges pluralistic ideals by promoting a singular, unified will that marginalizes dissenting voices (Mudde Reference Mudde2004; Rooduijn and Akkerman Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017). This simplification of complex political issues into clear-cut moral narratives not only converts public discontent into political capital but also reinforces a homogeneous identity that stands in stark contrast to the acceptance of diversity fundamental to pluralism (Galston Reference Galston2017). However, the relationship between populism and pluralism is not universally oppositional, thereby amplifying the complexity of their relationship. While anti-pluralism is a prominent feature, not all populism entirely rejects pluralistic values. Some populists, particularly those emphasizing inclusion and representation of marginalized voices, have contributed positively to democratic debates by challenging elitist dominance and invigorating political participation (Panizza Reference Panizza2005; Laclau Reference Laclau2005). This dual potential suggests that populism’s compatibility with pluralism may depend on contextual factors, including the nature of populist leadership and the broader political culture in which it operates.

The vulnerability of democracies to anti-pluralistic populism in weakly pluralistic contexts highlights the need for contextual exploration. The third wave of democratization, spanning from the mid-1970s to the early 1990s (Huntington Reference Huntington1991), revealed the challenges faced by newly established democracies in cultivating a robust commitment to pluralism (Shin Reference Shin1994; Diamond Reference Diamond1996; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Schedler Reference Schedler2001). Studies of the third wave of democratization have emphasized that countries within this wave remain in a fragile democratic state, with substantive democratic consolidation largely unachieved (Mainwaring and Bizzarro Reference Mainwaring and Bizzarro2019; Rose and Shin Reference Rose and Shin2001), and have warned that these nations are even more vulnerable to democratic backsliding (Wunsch and Blanchard Reference Wunsch and Blanchard2023). In these contexts, the relative absence of strong pluralistic values created an environment where anti-pluralistic sentiments could resonate more broadly, framing society through a dichotomous lens of the people versus the elite. This tendency to interpret political conflicts in binary terms is prone to deepening societal divisions and heightened polarization, subtly undermining the pluralistic norms necessary for democratic stability (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019; Mounk Reference Mounk2018; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017).

This leads us to an essential question: In what forms does populism manifest in contexts where the foundations for pluralism are relatively weak? This inquiry is significant for several reasons. First, it offers broad insights into the relationship between populism, democratic norms, and anti-pluralism, which is essential in the ongoing debate about the positive or negative impacts of populism on democracy. For instance, understanding these dynamics can shed light on whether populism serves as a corrective force or a detrimental influence in democratic systems. Second, the comparative study of populism is particularly important in third-wave democracies, where democratic norms are not deeply rooted. By analyzing how populism emerges in these contexts, this research contributes significantly to comparative political science by illustrating how populism operates across different levels of democratic development. This approach not only enriches the discourse on populism but also aids in developing more nuanced theories regarding the interplay between populism and democracy in various political environments.

In response to the above question, I first investigate that in countries with weak democratic norms, mainstream parties are more likely to rely on populism. This tendency from mainstream parties is not primarily driven by the strategic need to survive in the face of successful extreme niche parties, as often discussed in Western contexts (Schwörer Reference Schwörer2021), but rather due to the inadequate establishment of democratic norms within the party ecosystem itself. In such environments, the political landscape is highly unstable, and competition is intense, increasing the likelihood that parties will resort to more extreme measures to garner popular support (Schedler Reference Schedler2001). Populism can emerge as a potent strategy in these situations, as it effectively channels public dissatisfaction and anger through a simple, dichotomous narrative of the true people versus the corrupt elite (Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Additionally, in countries with weak democratic norms, political elites often fail to uphold pluralistic values, making populist messages more resonant. The lack of a robust democratic culture that respects and accommodates diverse opinions and interests makes it easier for populists to gain support by emphasizing a singular, unified voice (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2019).

Furthermore, as elections approach, mainstream political parties are often inclined to adopt populist rhetoric to capture public attention and garner support. This language is effective due to its concise, direct nature, and its ability to resonate emotionally with voters (Moffitt Reference Moffitt2016; Weyland Reference Weyland2001). Research on election dynamics, such as Koopmans (Reference Koopmans2004), shows that parties intensify their engagement with voters during campaigns. However, findings on the prevalence of populism during elections are mixed. Bonikowski and Gidron (Reference Bonikowski and Gidron2016) observed that in the U.S. two-party system, parties initially target their base with populist messages but then moderate their tone to appeal to the broader electorate as elections near. Conversely, Blassnig et al. (Reference Blassnig, Büchel, Ernst and Engesser2019) argued that populist rhetoric increases as parties intensify communication with potential voters during campaigns. This tendency is particularly pronounced in third-wave democracies, where weak democratic norms, intense political competition, and social conflict are prevalent (Diamond Reference Diamond1996). In these environments, political instability and widespread distrust of political elites make populist language a powerful tool for mainstream parties to capture public discontent and gain voter support.

In addition to the above, this paper also posits that populist rhetoric intensifies when parties are in opposition. In political systems like South Korea’s two-party dominant structure, parties alternate between governance and opposition roles, adopting different strategic approaches depending on their position (Breyer Reference Breyer2023). Existing literature on populism presents mixed views: while mainstream governing parties (MGPs) tend to be risk-averse to maintain their status and avoid alienating voters (Van de Wardt Reference Van de Wardt2015), mainstream opposition parties (MOPs) are often more willing to employ populist rhetoric to gain power (Jagers and Walgrave Reference Jagers and Walgrave2007). Studies in Western Europe found little difference in populist language use between MGPs and MOPs (Rooduijn and Akkerman Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017), whereas research in Greece observed that opposition parties were more populist in parliamentary debates (Vasilopoulou et al. Reference Vasilopoulou, Halikiopoulou and Exadaktylos2014), and similar trends were noted in Western countries’ social media (Ernst et al. Reference Ernst, Engesser, Büchel, Blassnig and Esser2017). This article contends that in contexts with weak democratic norms, the use of populism by opposition parties can become more pronounced. This pattern emerges because opposition parties in such contexts face fewer institutional constraints and weaker normative pressures that would otherwise deter excessive populist rhetoric. Additionally, in the absence of strong democratic norms, appealing to anti-elitist and people-centric narratives becomes a strategic tool for mobilizing discontent and challenging the legitimacy of the ruling establishment.

Lastly, it is essential to note that mainstream political parties, regardless of their ideological orientation, are likely to employ populist rhetoric. While Western studies often categorize populism into left-wing and right-wing variants, suggesting that the nature of populism differs according to party ideology, this article argues that in third-wave democracies, where democratic norms are not fully consolidated and party systems are unstable, all parties are inclined to adopt populist strategies to garner popular support. In these countries, the democratization process is relatively recent, leading to the incomplete establishment of democratic norms (Shin Reference Shin1994; Rose and Shin Reference Rose and Shin2001). Moreover, the instability of party systems, characterized by frequent mergers and splits among parties, tends to blur the ideological identity of these parties (Mainwaring and Torcal Reference Mainwaring and Torcal2006). This instability is one of the critical factors driving parties to adopt populist rhetoric as a means of securing public support. For instance, in South Korea, long-standing regional conflicts and weak linkages between parties and voters have been noted (Hyun Reference Hyun2021; Ryu Reference Ryu2012; Han Reference Han2016). Under such conditions, parties are likely to resort to populism, irrespective of whether they are on the left or right of the political spectrum.

Sectarian populism

As discussed earlier, understanding the manifestations of populism demands careful attention to the contexts of the countries. Particularly in political environments marked by weakly consolidated pluralist traditions and heightened polarization, populism frequently takes on distinctly anti-pluralist forms. In such contexts, populist actors often adopt strategies that explicitly reject pluralistic values, reflecting deep-rooted hostility and moralistic opposition toward their political rivals. In this study, I refer to this particular manifestation of populism, characterized by intense partisan division and moral condemnation of opponents, as sectarian populism.

Sectarian populism, fundamentally grounded in anti-pluralism, emphasizes several defining features. One notable characteristic is the erosion of mutual tolerance between competing political factions. Political actors within this framework systematically delegitimize and demonize their opponents, portraying them as corrupt or morally compromised elites, while positioning themselves as the authentic representatives of the people’s will. In contexts lacking robust democratic norms, such exclusionary strategies flourish, intensifying existing political divides and exacerbating social conflict. By simplifying complex political frustrations into clear, moralized narratives of good versus evil, political elites can more effectively mobilize support, capitalizing on widespread dissatisfaction as a political resource.

This form of populism exhibits notable parallels with political sectarianism, a concept initially introduced by Finkel et al. (Reference Finkel, Bail and Cikara2020) to describe the contemporary polarization in American politics. Political sectarianism refers specifically to an intense form of partisan polarization, in which political rivals are viewed not merely as ideological opponents but as fundamentally alien, morally compromised, and threatening entities. Such perspectives foster distrust and aversion among competing partisan groups, reinforcing political conflict by emphasizing irreconcilable differences and moral deficiencies in political adversaries (Garrett and Bankert Reference Garrett and Bankert2020; Garzia et al. Reference Garzia, da Silva and Maye2023; Masaru Reference Masaru2021; Ardovini Reference Ardovini2016). However, it is important to differentiate between political sectarianism and sectarian populism. While political sectarianism primarily emphasizes the deeply polarized and morally charged antagonism between rival partisan groups, sectarian populism further integrates key populist characteristics, such as a people-centric worldview, anti-elitist attitudes, and authoritarian rhetoric, thereby framing this partisan division explicitly as a struggle between the morally virtuous “true people” and a morally corrupt elite. Thus, sectarian populism represents a distinct subtype that fuses the moralistic and antagonistic dimensions of political sectarianism with the populist insistence on speaking exclusively on behalf of “the people” against an illegitimate elite.

This distinction of sectarian populism as a separate category allows for a more comprehensive understanding of populism in contexts where the traditional dichotomy of left- and right-wing populism is less pronounced. Unlike left-wing populism, which often centers on economic inequality (Guriev and Papaioannou Reference Guriev and Papaioannou2022), or right-wing populism, which emphasizes nativism and anti-immigration sentiments (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2009), sectarian populism transcends issue-specific frameworks. It retains the core elements of populism—such as anti-elitism, people-centrism, and moralization—but emerges in a more diffuse and adaptable form. By framing populism in this way, we can capture its manifestations across diverse political contexts, especially in environments marked by heightened polarization and weak democratic norms. Defining these dynamics as sectarian populism highlights the versatility of populist rhetoric and its ability to thrive beyond conventional ideological boundaries.

Sectarian populism is marked by a rigid moral dichotomy, deep-seated animosity, and an exclusionary framework that collectively reinforce its anti-pluralistic nature. Moralization stems from the belief that one’s side is morally righteous while the opposition is corrupt and immoral, allowing populists to claim they exclusively represent the true people. This moral superiority simplifies political debate and justifies party elites’ policies while discrediting opponents. Hostility further intensifies this dynamic by framing political competition as a battle between good and evil, where the opposition is treated as an enemy to be rejected. Party elites fuel this animosity through blame and attacks, transforming anger into political momentum. Finally, division solidifies sectarian populism by deepening the us-versus-them dichotomy, alienating opponents, and asserting that only populists can truly represent the people’s interests. This exclusionary nature of sectarian populism not only fosters political conflict but also erodes social cohesion, reinforcing the populists’ legitimacy through polarization.

This sectarian populism has the potential to permeate the populist rhetoric of both left- and right-wing parties. Left-wing parties, which have traditionally centered their populist arguments on economic inequality and distribution issues (Edwards Reference Edwards2010; Weyland Reference Weyland2013; Cameron Reference Cameron2009; Absher Reference Absher, Grier and Grier2020; Seligson Reference Seligson2007), may find that in environments of weak democratic norms, anti-pluralist elements such as moralization, hostility, and division become the primary tools for political mobilization. This could manifest in left-wing parties framing the opposition as corrupt elites and positioning themselves as the morally superior group, thereby attracting popular support.

Similarly, right-wing parties will also be influenced by sectarian populism. Traditionally emphasizing nativism and anti-immigration stances (Stanley Reference Stanley, Kaltwasser, Taggart, Espejo and Ostiguy2017; Pirro Reference Pirro2015, Reference Pirro2014; Santana Reference Santana, Zagórski and Rama2020; Becker 2010; Szabó et al. Reference Szabó, Norocel and Bene2019), right-wing populism may intensify its use of hostility and division in response to weakening democratic norms. Right-wing parties may begin to target not only immigrants but also political opponents, framing them as morally corrupt enemies, while asserting that they alone represent the interests of the true people. This strategy would further inflame public anxiety and dissatisfaction, thereby deepening social conflict.

Ultimately, sectarian populism is likely to impact both left- and right-wing parties equally. This form of populism, marked by moralization, hostility, and division, will manifest across the political spectrum as a strategy for securing public support, becoming especially pronounced in environments with weak democratic norms.

Building on this framework, I will empirically test how sectarian populism manifests in real-world political discourse, using South Korea as a case study. As one of the representative examples of the third wave of democratization (Rose and Shin Reference Rose and Shin2001; Huntington Reference Huntington1991; Im Reference Im2004), South Korea offers a compelling context for examining the dynamics of populism. Despite its democratic achievements, skepticism about the quality of its democracy persists (Lee Reference Lee2009; Shin Reference Shin2020; Eom and Kwon Reference Eom and Kwon2024), and recent research on populism in South Korea highlights the relevance of this inquiry (e.g., Yoon Reference Yoon2022; Shin and Kim Reference Shin and Kim2022; Do and Jin Reference Do and Jin2020; Jung Reference Jung2023; Do Reference Do2020). For instance, Han and Shim (Reference Han and Shim2021) suggested that South Korean populism manifests in dual forms, with people-centric populism strengthening democracy, as seen in the 2016–2017 candlelight protests, while exclusionary populism, exemplified by the Taegeukgi movement, threatens democratic stability. In addition to the growing body of literature on this topic, this study examines South Korea to explore the anti-pluralistic, sectarian form of populism, highlighting how these dynamics unfold within a political system where democratic norms are still developing and polarization remains a persistent challenge.

Methodology

Data

The study focuses on mainstream party statements from South Korea to provide a comprehensive view of the evolution of populism within the country over a decade (2012–2022). The necessity for this data arose from the lack of detailed political rhetoric data, which is crucial for understanding global populism trends. Notably, research has shown that online political discourse, particularly party statements during contentious election campaigns, offers valuable insights into the strategies parties use to mobilize public sentiment (Radziej and Molek-Kozakowska Reference Radziej and Molek-Kozakowska2022).

In evaluating party statements, the level of populism within parties was measured, with a focus on these statements for their authoritative nature and suitability for comparative content analysis. Issued regularly, ranging from once to several times a week, these statements, including press releases and texts from party press conferences, serve as official communications that reflect party ideologies and assessments of political events. Unlike speeches by party leaders, they are published under the party’s name on its official website, ensuring consistency in representation. Their broader appeal compared to election manifestos lies in their concise format, timely coverage of urgent issues, and use of less formal language (Schwörer Reference Schwörer2021). Moreover, these statements are systematically accessible through web scraping techniques, making them a practical data source for analyzing populist rhetoric over time.

The dataset includes statements from South Korea’s mainstream political parties, namely the Democratic Party of Korea, a progressive party, and the People’s Power Party, a conservative party. In total, the dataset spans from January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2022, encompassing 52,487 documents, with 28,451 from the Democratic Party of Korea and 24,036 from the People’s Power Party. Election periods are defined as the three months surrounding presidential elections, including two months preceding and one month following the election. Furthermore, opposition periods are identified based on intervals when either party was not the ruling party.

The analysis employs longitudinal computer-aided content analysis of party statements to identify and measure the level of populism within these parties over time. This approach allows for a systematic examination of political rhetoric and its evolution within the context of South Korean politics.

Classification

In recent years, the swift advancement of LLMs (Du et al. Reference Du, Narang and Ramesh2022; Ouyang et al. Reference Ouyang, Wu and Jiang2022; Touvron et al. Reference Touvron, Lavril and Izacard2023; Thoppilan et al. Reference Thoppilan, De Freitas and Hall2022) has marked a pivotal milestone in the evolution of artificial intelligence, creating opportunities for broader research across various academic disciplines. With the growing body of literature on LLMs, there has been a notable increase in studies validating the annotation capabilities of these models for classification tasks (Heseltine and von Hohenberg Reference Heseltine and von Hohenberg2024; Wu et al. Reference Wu, Nagler, Tucker and Messing2023; Huang et al. Reference Huang, Kwak and An2023; Gilardi et al. Reference Gilardi, Alizadeh and Kubli2023; Tornberg Reference Tornberg2023).

In this research, I implemented a series of sequential procedures to classify populism in political texts, combining the holistic grading approach widely used in populism studies with the analytical capabilities of LLMs. The primary objective is to capture the nuanced manifestations of populism by leveraging document-level classification that considers the full context of each text. This approach is aligned with the holistic grading scale established by Chrysogelos et al. (Reference Chrysogelos, Hawkins, Hawkins, Littvay and Wiesehomeier2024), which evaluates populism on a continuous scale ranging from 0 to 2. A score of 0 indicates the absence of populist elements, 1 signifies the presence of such elements inconsistently, and 2 reflects a fully consistent presence of populism. To refine the analysis further, this scale allows for continuous values up to one decimal place, preserving the granularity of the assessment.

The first step in the methodology involves prompt engineering tailored to the nature and context of the texts. Effective prompt engineering is crucial for enhancing the accuracy of LLMs, as emphasized in the literature (Perez Reference Perez, Kiela and Cho2021; Webson and Pavlick Reference Webson and Pavlick2021). I employed the Chain-of-Thoughts (CoT) approach to prompt engineering, which has been shown to significantly improve LLM performance by guiding the model through a step-by-step reasoning process (Wei et al. Reference Wei2022; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Zhang, Li and Smola2022). This approach began by providing the LLM with a definition of populism derived from the literature and adopted in this study, as mentioned above. Subsequently, the LLM was tasked with identifying and evaluating six core elements of populism within each text: Manichean view, cosmic proportion, people-centrism, anti-elitism, elite subversion, and authoritarian rhetoric. This element-based analysis provided a structured pathway for the LLM to assess the presence and consistency of populist elements systematically. Following this evaluation, the LLM assessed the extent to which the text exhibited populism on the 0–2 scale, based on the previously defined criteria and elements.

In the second step, the LLM was required to articulate its reasoning explicitly for each classification decision. This requirement was informed by recent findings suggesting that LLMs produce more accurate and reliable outcomes when they are prompted to provide explanations for their responses rather than performing the task directly (Wei et al. Reference Wei2022). By incorporating this explanation mechanism, I aimed to enhance the performances of the classification process, allowing for a deeper understanding of how the LLM interpreted the texts relative to the holistic grading scale.

The third step extended the classification beyond the presence of populism to identify specific types of populism. After the initial classification, the LLM was prompted to categorize the populism detected into one of four predefined types based on their thematic focus. The first category was economic populism, often associated with left-wing movements emphasizing economic inequality and framing the conflict as one between the people and the elite. This form of populism is particularly prevalent in Latin America. The second category was immigration nativism populism, characterized by anti-immigrant sentiment and primarily observed in Eastern Europe, where immigrants are portrayed as a threat to the livelihoods of the “pure people,” with elites blamed for enabling this threat. The third category, security populism, was relevant to contexts like South Korea, where national security concerns—arising from the ongoing conflict with North Korea, historical tensions with Japan, and complex relations with China—are used to frame foreign entities as threats, casting political leaders as saviors. The fourth category, political sectarianism populism, focused on partisan divisions and the absence of fully consolidated democratic norms, particularly in South Korea. This type of populism retains traditional populist elements but emphasizes political partisanship as the basis for the us-versus-them dichotomy, with moral conflict at its core (Finkel et al. Reference Finkel, Bail and Cikara2020; Garzia et al. Reference Garzia, da Silva and Maye2023). Populist expressions that did not fit into these categories were classified as “Other,” ensuring comprehensive coverage of potential variations in populism.

For the implementation of these steps, I employed ChatGPT 3.5-turbo, which has demonstrated a high level of accuracy in text classification tasks according to recent studies (Ye et al. Reference Ye, Chen and Xu2023). The choice of this model was informed by its proven capabilities in handling complex text analysis and its ability to incorporate contextual information effectively. Throughout the classification process the LLM’s outputs were continuously monitored to ensure consistency with the theoretical framework and coding criteria.

The final step involved a comprehensive validity check to mitigate potential biases and ensure the robustness of the results. To this end, two independent coders, extensively trained in the theoretical and methodological foundations of the classification criteria, were tasked with evaluating a stratified random subset of the dataset. This subset was designed to represent a balanced mix of different levels and types of populism classifications. The coders independently assessed this subset to cross-verify the consistency and reliability of the LLM’s classifications. Intercoder reliability was evaluated using Cohen’s kappa, which yielded a high level of agreement (𝐾 = 0.84), indicating strong reliability in the classification process. This validation step not only reinforced the credibility of the LLM’s outputs but also highlighted the robustness of the methodological approach adopted in this study.

Empirical results

Populism

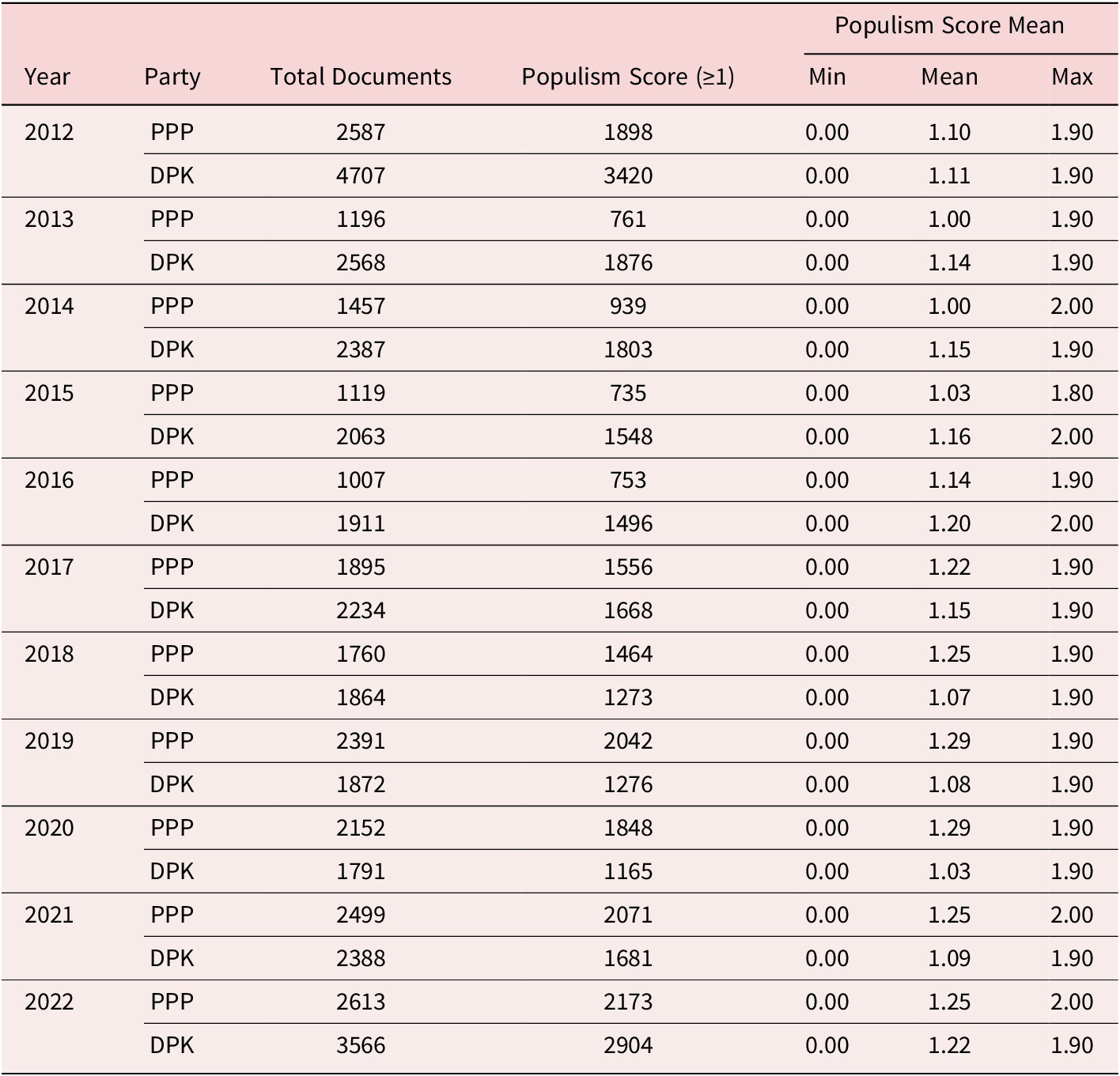

As shown in Table 1, the classification results for populism from 2012 to 2022 summarize trends in both PPP and DPK. The mean populism score exhibits a gradual increase, rising from 1.10 in 2012 to between 1.22 and 1.25 for both parties in 2022. While this upward trend suggests a growing presence of populist rhetoric, it is important to note that the classification scale ranges from 0 to 2. This indicates that although the level of populism remains moderate, a substantial proportion of statements contain at least some populist elements. As discussed in the theoretical section, populism in this study is classified based on the definition proposed by Hawkins (Reference Hawkins2009), which forms the foundation of my analytical framework. The classification results illustrate this definition in practice, as seen in the following examples.

Table 1. Populism score trends by year and party

A notable example of a statement receiving a populism classification score of 1.8 is the People Power Party statement from January 1, 2022, exemplifies this approach, portraying systemic corruption, an existential crisis, and an urgent need for action.

Amid the worst youth unemployment crisis in history due to the failures of the Moon Jae-in administration, this news is infuriating. Parents of job-seeking youth must feel devastated. This is not “merit” but “privilege.” The cartel of vested interests surrounding Lee Jae-myung has already solidified. There are countless cases of the cartel around Lee benefiting from illicit gains. This is the true face of Lee’s version of fairness. The dark reality of the cartel surrounding Lee is being fully exposed.

The statement, which received a populism classification score of 1.8, embodies Manichaean dualism, portraying Lee Jae-myung and his associates as a corrupt elite while positioning job-seeking youth and their families as the suffering majority. Phrases like “cartel of vested interests” and “politics that serve only one’s own associates” reinforce this division, presenting political competition as a battle between good and evil rather than a debate over policies. It also amplifies cosmic proportions, framing youth unemployment as the worst in history due to government failure. The phrase “dark reality of the cartel” suggests widespread corruption, transforming a hiring controversy into a systemic threat to democracy. By linking this case to past scandals, the statement implies an entrenched and pervasive conspiracy.

People-centrism emerges through rhetorical appeals to public outrage. The phrase “parents of job-seeking youth must feel devastated” personalizes the issue, fostering identification with affected citizens. The assertion that Lee Jae-myung’s governance contradicts fairness suggests betrayal, reinforcing the narrative that the people must reclaim justice from the elite. The statement also strongly reflects anti-elitism, emphasizing corruption within political and economic power structures. The repeated use of “cartel” implies an exclusive network enriching itself at the public’s expense, while direct accusations of bribery and cronyism paint political elites as fundamentally illegitimate. Lastly, authoritarian rhetoric surfaces in the language of exposure and urgency. The phrase “being fully exposed” suggests that corruption is finally coming to light, calling for decisive action. The implication that normal political processes are insufficient fuels a sense of crisis, justifying extraordinary measures against the alleged elite.

Another example is the statement from April 1, 2012, from the opposition party, the Democratic Party of Korea, which exemplifies key rhetorical strategies characteristic of populist discourse. The statement constructs a narrative of national crisis, vilifies the political elite, and positions the opposition as the sole legitimate voice of the people—key characteristics of populist discourse.

The Republic of Korea is collapsing. The dirty politics of surveillance and monitoring of citizens has resurfaced like a ghost, dismantling the free and just Republic of Korea. The essence of this issue is clear: it is an indiscriminate investigation of citizens led by the Blue House. Such an event is unimaginable in a democratic society. Even more alarming is that two years ago, when this issue first came to light, the Blue House systematically covered it up by offering money and suppressing the prosecution’s investigation. The president must answer the questions of the people.

The statement employs a Manichaean worldview, dividing political reality into an absolute struggle between good and evil. The phrase “the Republic of Korea is collapsing” suggests an existential crisis, blaming “dirty politics” for the nation’s decline. This stark dichotomy is a hallmark of populist rhetoric, as it frames politics as a battle between a morally pure people and a corrupt elite. It also invokes cosmic proportion, heightening the severity of the conflict by suggesting that national survival is at stake. The assertion that surveillance politics is “dismantling the free and just Republic of Korea” amplifies the perception of an imminent democratic breakdown, creating a sense of urgency that mobilizes public sentiment against the ruling elite.

The statement strongly reflects anti-elitism, depicting the Blue House as orchestrating “indiscriminate investigations” against citizens. By portraying the government as an oppressive force working against the interests of the people, the rhetoric fuels distrust in institutional authority and aligns with the populist tendency to delegitimize traditional governance structures. Additional examples can be found in Sections A.4 and A.5 of the supplementary materials.

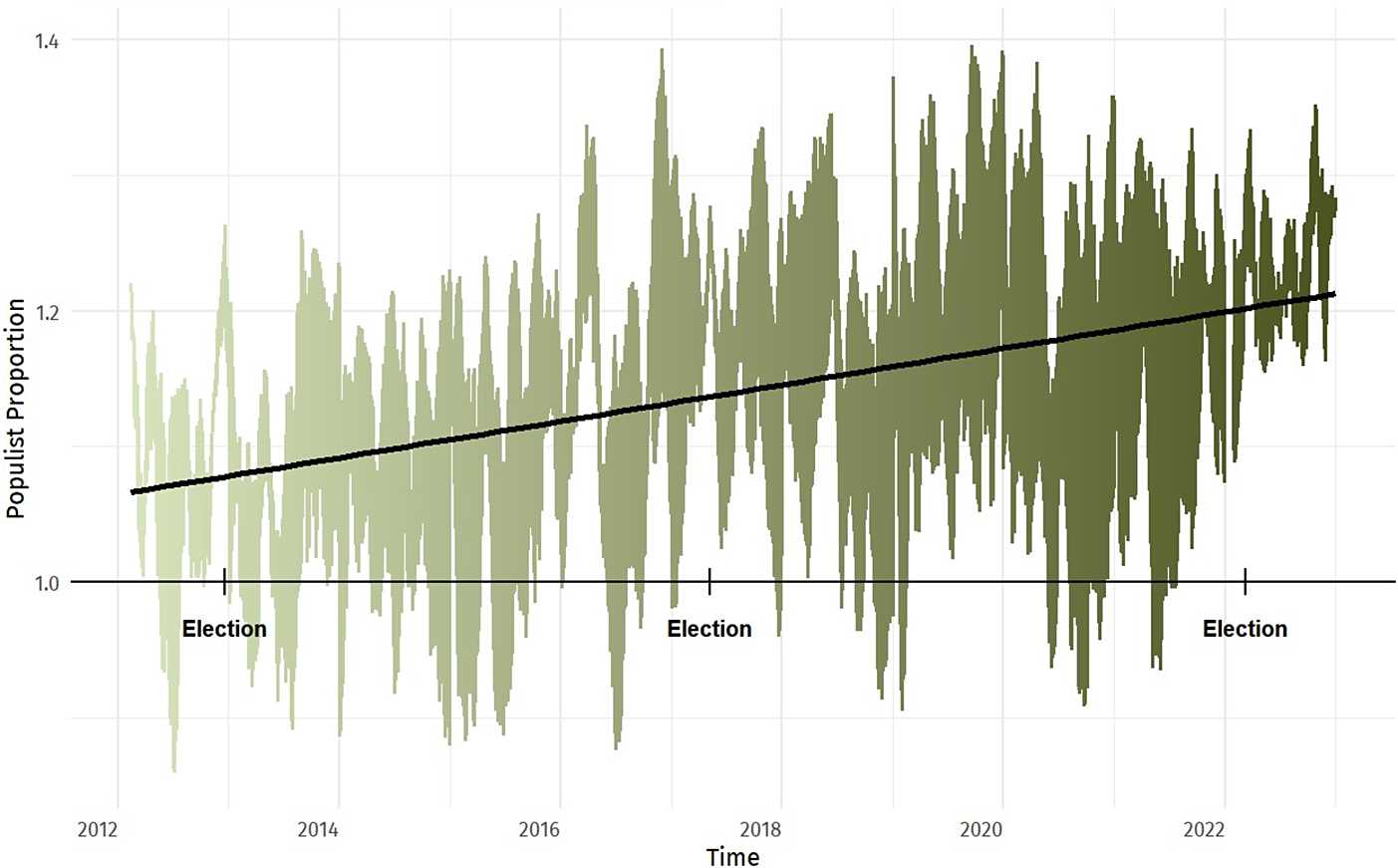

Examining the overall time series trend of populism, as depicted in Figure 1, the classification of these statements on a 0–2 scale, where a score of 1 or higher indicates the presence of populist elements, reveals a consistent, albeit slight, upward trajectory. This figure illustrates the cumulative progression of populist discourse within mainstream political parties during the period studied. This increase, while slight, is significant in understanding the broader political shifts during this decade. The consistent rise in populist rhetoric suggests that mainstream parties may have increasingly relied on populist strategies to resonate with public sentiment and to navigate the evolving political landscape.

Figure 1. Time Series of Populist Proportion in South Korea.

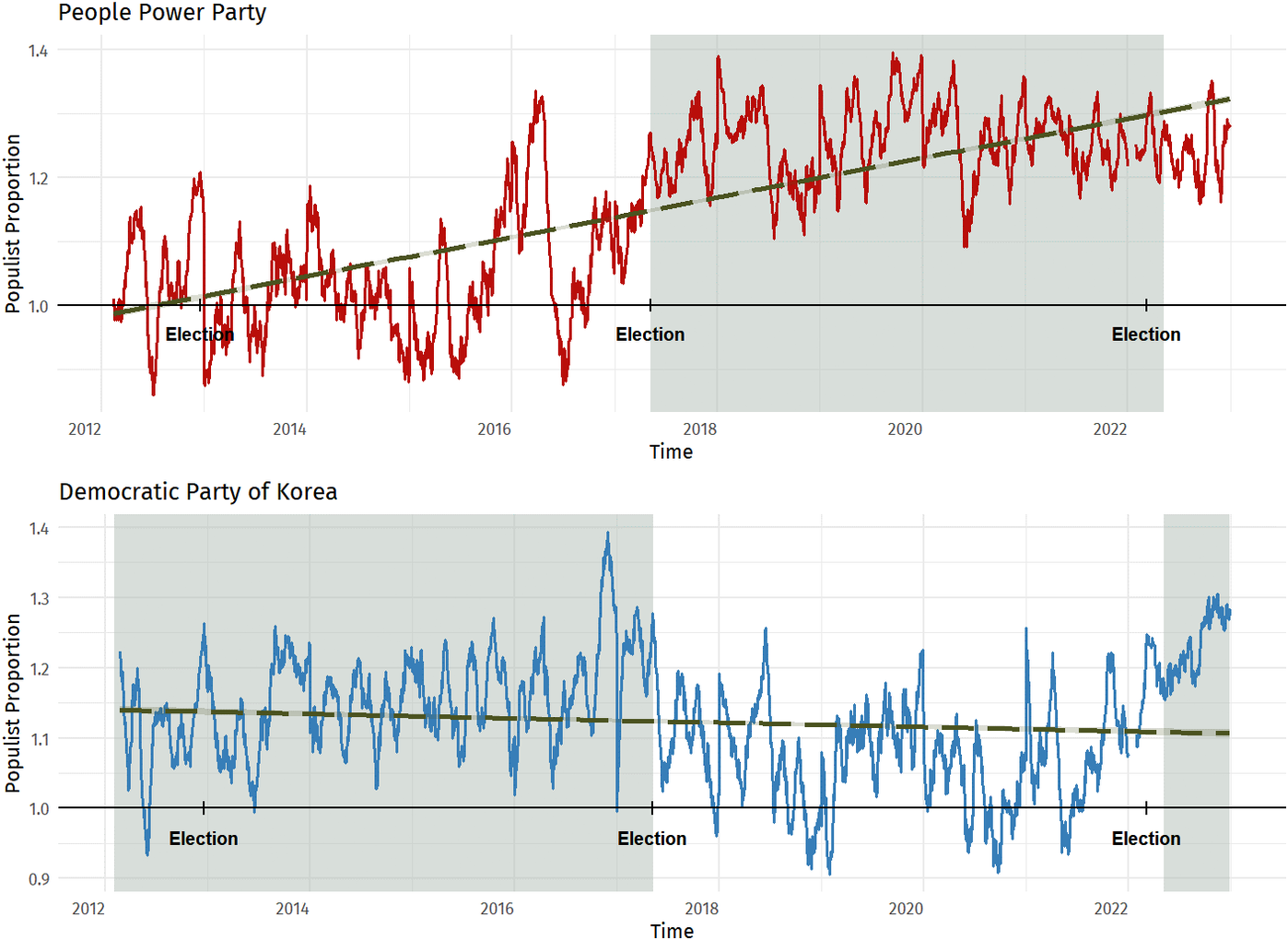

Figure 2 extends the analysis presented in Figure 1 by disaggregating populist trends according to party affiliation. This figure not only illustrates the overall time-series trajectory of populist rhetoric but also highlights critical junctures such as election periods and intervals during which a party held governing power. Considering that the populism metric is scaled from 0 to 2, the consistently high scores, exceeding 1.0 for both PPP and DPK, indicate that populist discourse is deeply entrenched in the political communication strategies of both parties.

Figure 2. Populism by Political Party.

Note: The shaded areas indicate the periods when the respective party was in opposition.

In the case of the PPP, populism scores remained predominantly below 1.0 until the 2016 period. However, from the 2017 election cycle onward, the PPP has consistently registered scores above 1.0, suggesting a marked intensification in populist rhetoric. Similarly, the DPK exhibits a robust populist tendency, with scores consistently above 1.0 during the period from 2013 to 2018. Although the intensity of populism within the DPK appeared to subside somewhat after 2018, recent data indicate a renewed upward trend, underscoring the dynamic nature of political discourse.

Moreover, the temporal patterns depicted in Figure 2 suggest a correlation between electoral events and the use of populist language. Periods immediately preceding and following elections often serve as catalysts, triggering significant surges or spikes in populist rhetoric. For example, the PPP experienced a notable spike during the 2012 election, and the 2017 electoral cycle appears to have functioned as a trigger for an overall escalation in populist expression. Although the 2022 election did not produce an abrupt spike, the entrenched nature of populist language in party manifestos implies that the electoral context may have contributed to the consolidation of an already established trend. In parallel, the DPK recorded distinct spikes in populism during the 2013 and 2022 elections, while the 2017 cycle, despite lacking an immediate spike during the election month, witnessed a peak in populism just before the election, indicating a prolonged impact of electoral dynamics.

The figure further incorporates an analysis of party status by employing shaded segments to denote periods when a party functioned as the opposition. This visualization reveals that both parties exhibit heightened populist rhetoric during their opposition stints. For instance, following the defeat of PPP candidate Hong Jun-pyo by DPK candidate Moon Jae-in in the May 7, 2017, election, the PPP, which was subsequently moved into the opposition camp, demonstrated a sharp increase in populist rhetoric from 2017 compared to its earlier performance between 2012 and 2017. A similar pattern is observed for the DPK; from 2012 until the election of Moon Jae-in in 2017, during which time the DPK served as the opposition, it maintained higher populism scores relative to its period as the ruling party. Furthermore, after Moon Jae-in took office, the DPK’s populism diminished temporarily; however, following the March 9, 2022 presidential election, when the DPK returned to the opposition after its candidate Lee Jae-myung lost to PPP candidate Yoon Seok-youl, there was an abrupt resurgence in populist rhetoric.

Collectively, these observations provide descriptive evidence that both electoral cycles and a party’s governing status significantly influence the intensity and character of populist rhetoric. The findings underscore that populist discourse is not merely a static ideological expression but is dynamically calibrated in response to the changing political landscape, particularly in relation to elections and shifts between government and opposition roles.

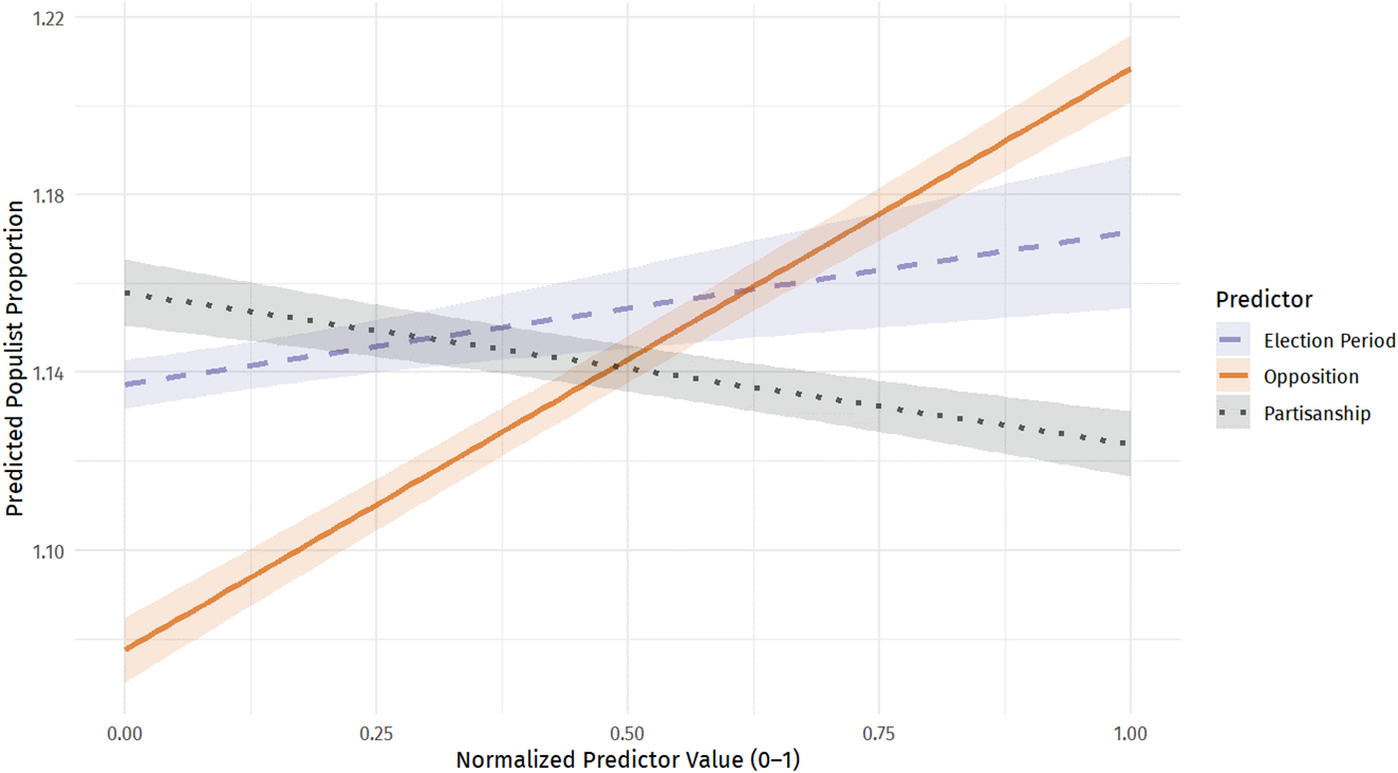

Building on the patterns identified earlier, this study aimed to further examine the association of various factors on the proportion of populism. In order to illustrate these results from the regressional model, Figure 3 examines how changes in partisanship, opposition status, and election periods relate to the proportion of populism. For this analysis, each independent variable was examined in isolation by holding other variables at their mean values, thereby enabling a focus on the main effects of each variable without the confounding influence of interaction effects. This approach allowed for a clearer understanding of how each factor independently affects populist rhetoric. Additionally, to minimize scale disparities among the variables and enhance the interpretability of the results, this study employed 0–1 normalization, which standardized the variables to a common scale between 0 and 1.Footnote 1

Figure 3. Election Period, Opposition, Partisanship, and Populism.

The results depicted in Figure 3 indicate that partisanship, election periods, opposition status, and time significantly influence the proportion of populism. Notably, the findings reveal that as partisanship increases (i.e., as it becomes closer to DPK), the proportion of populism decreases. This suggests that the PPP employs populist rhetoric more frequently than the DPK. This result aligns with the descriptive findings presented earlier, which demonstrated that the PPP progressively adopts more populist discourse compared to the DPK. This trend implies that the PPP has strategically utilized anti-elitist narratives and moral dichotomies to appeal to the public.

Additionally, the variables of opposition status and election periods show significant positive effects on the proportion of populism, thereby confirming the descriptive findings from the previous figures. The significant positive effect of opposition status indicates that populist rhetoric intensifies when a party is in opposition. This pattern suggests that opposition parties strategically employ populist language to simplify and emotionally convey public grievances, thereby mobilizing their support base and criticizing the government. Similarly, the significant coefficients for election periods imply that parties tend to use populist rhetoric more frequently as elections approach. This tendency highlights the role of elections as a catalyst for amplifying populist discourse, with parties seeking to appeal to voters’ emotions more intensively during these times. Furthermore, consistent with the findings shown in Figure 1, the significant positive effect of time suggests that populist rhetoric has steadily increased over time. This trend indicates that the spread of populism in South Korean politics is not a temporary phenomenon but a structurally entrenched trend.

The observed increase in populism scores for both PPP and DPK from 2012 to 2022 from the figures can be understood within the broader context of South Korea’s political landscape as a third-wave democracy with weakly consolidated pluralistic norms. The trend of rising populist rhetoric aligns with the challenges faced by nascent democracies, where political competition often simplifies complex socio-political issues into binary conflicts between “the people” and “the elite.” In South Korea, the persistence of intense partisanship (Lee Reference Lee2015; Jo Reference Jo2022), regionalism (Kwon Reference Kwon2004; Hundt and Kim Reference Hundt and Kim2011), and ideological polarization (Han Reference Han2021; Cheong and Haggard Reference Cheong and Haggard2023) have provided fertile ground for populist narratives that emphasize anti-elitism and people-centrism. Both parties have strategically employed populist rhetoric, especially during election periods and while in opposition, to mobilize voter support by appealing to the public’s discontent with existing elites. This pattern underscores how mainstream parties, irrespective of their ideological leanings, have increasingly resorted to populist strategies as a means to navigate a polarized political environment and maintain electoral competitiveness. Moreover, the cyclical nature of populism in South Korea, characterized by its heightened use during opposition periods, reflects the instrumental role of populist rhetoric as a political tool. The PPP’s escalated use of populism following its 2017 electoral defeat and the DPK’s surge in populist discourse after its 2022 defeat highlight how shifts between government and opposition status influence the intensity of populist language. The gradual but consistent increase in populism scores reflects broader global patterns where political environments characterized by fragile democratic norms and limited pluralistic traditions are more susceptible to populist rhetoric. The observed trends in South Korea underscore how such conditions can create a fertile ground for mainstream parties to adopt populist strategies, offering broader insights into the challenges that emerging democracies may face in maintaining democratic stability and pluralism.

Sectarian populism

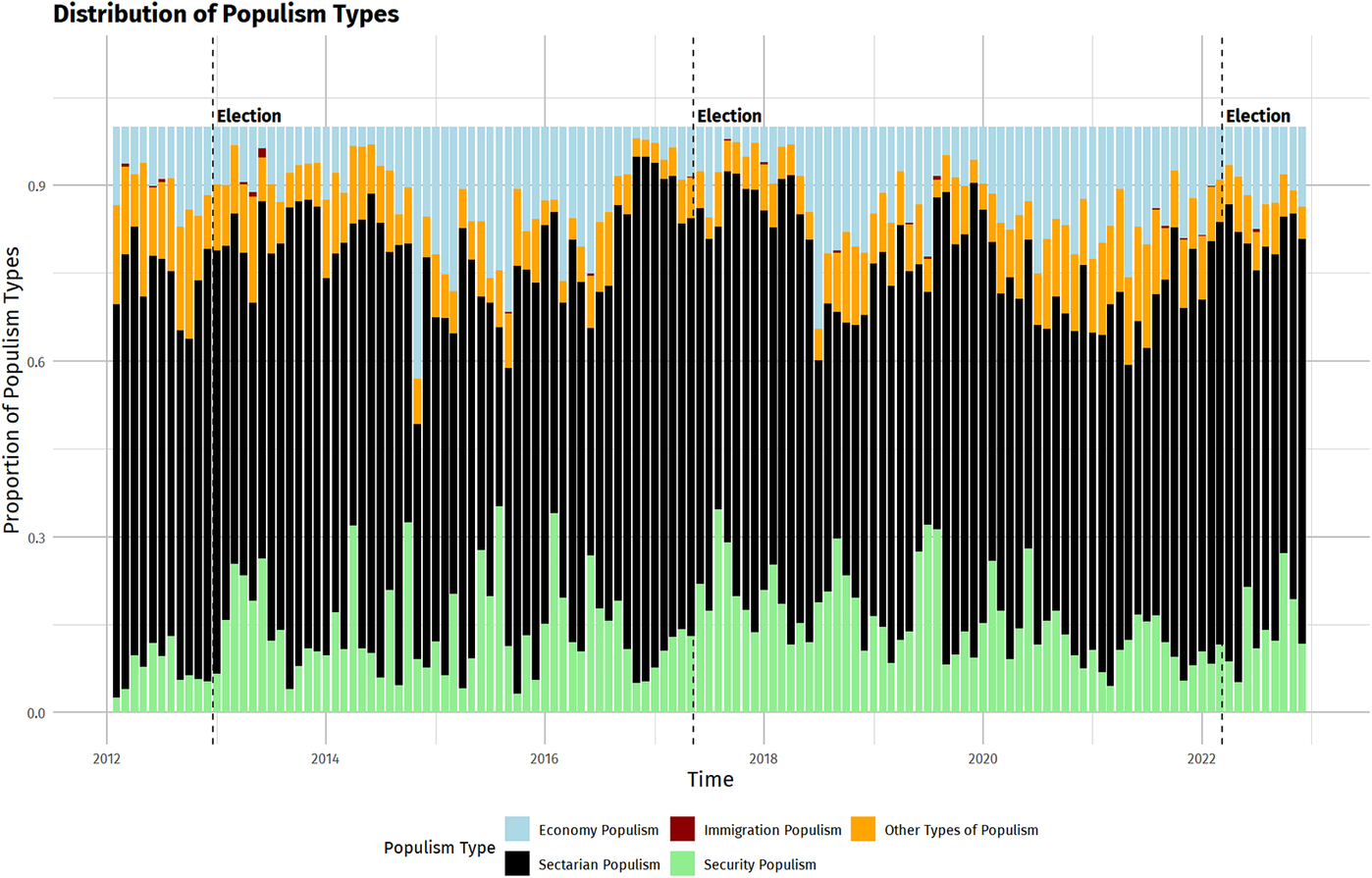

The previous section explored the overall trends in populism and the factors influencing them. How, then, does sectarian populism, a specific form of populism discussed earlier, manifest itself? To address this, I conducted a thematic classification of populism into five subtypes: economic populism, immigration populism, sectarian populism, security populism, and other forms of populism. As shown in Figure 4, sectarian populism consistently dominated the discourse from 2012 to 2022. Unlike Latin America, where economic populism is prevalent, or Western Europe, where immigration populism is more dominant, South Korea presents a distinctive pattern. Although economic populism emerges as the second or third most prominent subtype, immigration populism is virtually absent except for a few isolated periods. This absence suggests that immigration issues have not yet been heavily politicized within South Korean party competition. In contrast, security populism stands out as a significant subtype, almost on par with economic populism. Given South Korea’s geopolitical context—bordered by non-democratic neighbors like China and North Korea—security populism’s prominence reflects the salience of national security concerns. These findings underscore how the prevalence of specific populist subtypes is deeply intertwined with the political, social, and historical contexts of each country, highlighting the importance of more rigorous investigation into comparative populism.

Figure 4. Sectarian Populism (Proportion).

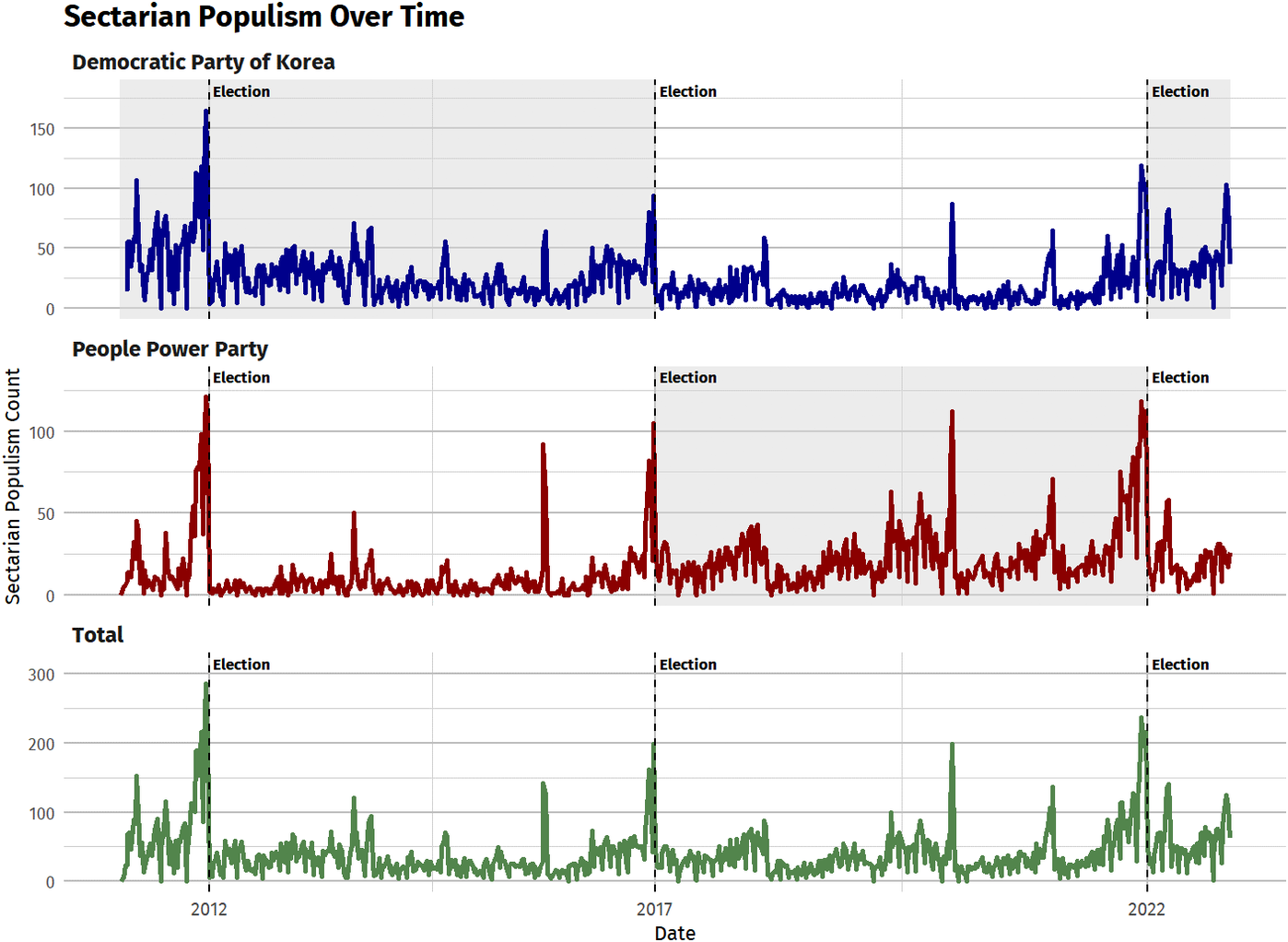

Given the overwhelming dominance of sectarian populism, the next step is to examine its patterns within individual parties and assess the influence of election periods and opposition status. For this purpose, I constructed Figure 5, which illustrates the trends in sectarian populism for DPK, PPP, and all parties combined. Intriguingly, the patterns across these three categories show a remarkable degree of similarity. As depicted in Figure 5, the time-series trends for both DPK and PPP, as well as the overall trends, align closely. First, both parties exhibit a pronounced increase in sectarian populism as elections approach, followed by a steep decline immediately after elections—a pattern that recurs consistently in every election cycle. This suggests that sectarian populism is strategically employed to maximize voter appeal during election campaigns. Moreover, opposition status appears to play a crucial role. The DPK’s use of sectarian populism is notably higher during periods when it was in opposition compared to when it held governing power. A similar pattern is observed for the PPP, indicating that opposition parties in South Korea strategically adopt sectarian populism to mobilize support by framing the political landscape as a moral struggle between the people and the corrupt elite.

Figure 5. Sectarian Populism (Count).

Note: The shaded areas indicate the periods when the respective party was in opposition.

The predominance of sectarian populism in South Korea’s political landscape, especially during election periods and among opposition parties, can be understood through the lens of its anti-pluralist characteristics. Unlike other forms of populism that focus on economic or immigration issues, sectarian populism thrives in environments with weakly consolidated democratic norms, where polarization and partisanship are deeply entrenched. The strategic use of sectarian populism by both PPP and DPK reflects an effort to appeal to core supporters by framing political competition as a moral struggle between the virtuous “true people” and the corrupt elite. The recurring pattern of heightened sectarian populism during elections suggests that parties exploit anti-pluralist rhetoric to consolidate support, presenting the opposition as an existential threat to national identity and democratic integrity. This strategic deployment not only amplifies political divisions but also challenges the development of pluralistic discourse, a fundamental element for democratic consolidation.

The implications of this reliance on sectarian populism are profound for South Korea’s democratic stability. The intensification of sectarian rhetoric during opposition periods illustrates how populism can be wielded as a tool for undermining incumbent legitimacy and fostering a zero-sum view of politics. This dynamic is particularly problematic in nascent democracies where institutional checks and balances are still evolving. The dominance of sectarian populism risks transforming elections from mechanisms of democratic accountability into battlegrounds of moral condemnation, where compromise and consensus become increasingly difficult to achieve. Over time, this could erode public trust in democratic institutions, deepen political polarization, and hinder the development of a robust, pluralistic democracy. Addressing these challenges requires a critical examination of how mainstream parties adopt and normalize populist strategies, highlighting the urgency of reinforcing pluralistic norms to counteract the divisive effects of sectarian populism.

Discussion and conclusion

This study set out to explore the manifestations and implications of populism within South Korea’s two main political parties, the People Power Party and the Democratic Party of Korea, over the decade from 2012 to 2022. The primary question addressed was how populism, particularly sectarian populism, has evolved in a third-wave democracy with weakly consolidated pluralistic norms.

Employing a longitudinal content analysis of political statements from mainstream parties using advanced large language models, this study finds evidence of a notable rise in populism within South Korea’s political landscape. The results indicate a steady increase in populist discourse over the past decade, highlighting significant associations with electoral timing and opposition party status. Specifically, the intensity of populist rhetoric escalated considerably during election cycles, suggesting strategic deployment by parties seeking to mobilize voter support. Similarly, opposition parties were more likely to engage in heightened populist language compared to when they held governing status, underscoring populism’s role as a potent mechanism to critique incumbents and consolidate opposition support.

Moreover, among the various forms of populism, sectarian populism emerged as distinctly dominant. Defined by heightened moral polarization, intense hostility toward political adversaries, and entrenched partisan division, sectarian populism was consistently and extensively employed by both mainstream parties. Notably, its prominence surged significantly during election campaigns and when parties were relegated to opposition status. This pattern illustrates how South Korea’s political parties strategically exploit sectarian populism to frame political conflicts as moral struggles between a morally righteous people and a purportedly corrupt elite. Such rhetoric intensifies existing partisan divides, presenting significant risks for democratic consolidation and pluralistic political culture in South Korea’s evolving democracy.

The findings from the study also suggest that the distinction between left-wing and right-wing populism in South Korea is less pronounced than commonly assumed. Although differences exist in degree, both ideological camps exhibit substantial populist tendencies, with a strikingly similar reliance on sectarian populism. This convergence underscores the strategic rather than ideological nature of populist rhetoric in South Korea’s polarized political landscape. More broadly, these results challenge traditional dichotomies in populism research that frame left- and right-wing populism as fundamentally distinct. Instead, they highlight how populist discourse can become embedded across ideological spectrums when democratic norms remain fragile. Given that sectarian populism can thrive on deepening partisan divisions and moralizing political conflict, its prevalence across both parties raises important concerns about its long-term implications for democratic consolidation.

This study underscores the necessity of expanding comparative populism research, particularly in contexts where populism has been understudied. As this analysis demonstrates, populist rhetoric is not exclusive to well-documented cases in Western democracies; rather, it emerges across diverse political systems, often taking distinct forms shaped by national contexts. Even in countries where populism has been perceived as marginal, it manifests in ways that warrant systematic comparative analysis. Understanding these variations is crucial not only for refining theoretical frameworks but also for assessing the broader implications of populism’s role in democratic and non-democratic settings.

Furthermore, these findings have significant implications for third-wave democracies, where democratic consolidation remains incomplete. The presence and potential rise of populism in these contexts suggest that political instability and weak institutional safeguards create fertile ground for populist mobilization. In particular, sectarian populism—a form of populist rhetoric that deepens partisan divisions and moralizes political conflicts—poses a serious challenge to democratic stability. Given that third-wave democracies, including South Korea, have long grappled with concerns over their democratic resilience (Shin and Moon Reference Shin and Moon2017; Croissant Reference Croissant2002; Yeo Reference Yeo2020), the increasing reliance on sectarian populism by mainstream parties raises urgent questions about its long-term effects on pluralism and democratic governance.

Building on this discussion, several avenues can be explored to deepen our understanding of sectarian populism and its broader implications. First, comparative studies examining the use of sectarian populism across different third-wave democracies could provide valuable insights into the conditions under which mainstream parties resort to populist rhetoric. Second, exploring the impact of sectarian populism on voter behavior and democratic legitimacy could shed light on the long-term consequences of anti-pluralist rhetoric for democratic stability. Third, investigating the role of media and digital platforms in amplifying sectarian populism may offer a deeper understanding of how populist narratives gain traction in polarized political environments. Lastly, a closer examination of the internal dynamics of mainstream parties and their strategic calculations regarding populist rhetoric could help elucidate the incentives driving the adoption of sectarian populism.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the broader literature on populism and democracy by demonstrating how sectarian populism functions as a strategic tool for mainstream parties in a third-wave democracy. The findings underscore the urgency of addressing the normalization of anti-pluralist rhetoric and reinforcing pluralistic norms as essential steps toward ensuring the sustainability of democratic governance. As third-wave democracies continue to grapple with the challenges of populism, understanding the dynamics of sectarian populism and its implications for democratic stability remains a crucial area for further research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this articlecan be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2025.13.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all those who provided valuable insights and support throughout the completion of this research. Their encouragement and feedback have been deeply appreciated.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.