… all investigations of political corruption are political in nature.

To believe any different is, by definition, an oxymoron.

Frederick Martens (Woodiwiss Reference Woodiwiss2015, 66)

Samuel Huntington once proposed that corruption was a sign of progress in developing societies. It showed that such societies had moved beyond the use of violence to negotiate a political order. Today, corruption is no longer seen in such benign light. Instead, conventional wisdom now suggests that corruption is a hindrance to development (see Mauro Reference Mauro, Heidenheimer and Johnston2002; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2015; Rose-Ackerman and Palifka Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016). In short, governments should be tackling corruption. And while we do see this, in reality such efforts often fail. With the oft-cited Singapore exception, anti-corruption agencies frequently fall victim to the very crimes they are tasked to eradicate (Svensson Reference Svensson2005).

All this suggests the politicized nature of anti-corruption efforts. Corruption charges can be levied against political opponents as an instrument of repression; they can also be used to remove troublesome coalition allies to consolidate power. In this article, we shift the focus of corruption charges away from simply who charges whom, but to who charges whom—when. To do so, we look at one single case, Indonesia. We outline how dynamics internal to the country shape the pattern of major corruption charges—i.e., cases that garner international attention. We ask: Do major corruption charges follow the Indonesian presidential electoral cycle—and if so, how? We argue that major corruption charges against government coalition members are more likely to happen before—but not too close to—an election. This timing allows the government to remove intra-coalition rivals, prevents politicians from defecting to a new party, and replaces vacancies with loyal allies. Conversely, major corruption charges against opposition members are more likely to happen post-election, to give the legal process time to unfold, to remove critical veto players from legislative processes, and to allow the government to credit-claim. And finally, if the who and the when are electorally motivated, we should see no discernable pattern when it comes to prominent charges against civil servants.

We test our argument on Indonesia in the years 1998–2015. We scrape all mentions of major corruption charges in the Associated Press and identify the political affiliation of each named individual. We find a significant relationship between electoral calendars and these major corruption charges—but conditional on whether the person charged is a member of the government coalition, the opposition coalition, or the civil service. These results are robust to different estimators. Moreover, they disappear when we shift the focus to major corruption convictions—i.e., outcomes that require a longer timeline than the electoral one—or all judicial activities.

Politicizing corruption

Research on the political uses of corruption charges has generally lagged behind extant studies of the concept, causes, and effects of corruption—from petty theft to access money (Ang Reference Ang2020), from street-level bribes to major corruption scandals. Yet, as the article's opening epigraph suggests, some works take the politicized aspect of corruption charges as given (Anechiarico and Jacobs Reference Anechiarico and Jacobs1996). There is a noticeable dissonance. On the one hand, there is international consensus pressing for international mechanisms of corruption control (Abbot & Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal2002; Bukovansky Reference Bukovansky, Cooley and Snyder2015; Cooley and Snyder Reference Cooley and Snyder2015; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2015; Noonan Reference Noonan1984). On the other hand, there are more qualified (if not cynical) observations—drawn mostly from case studies at various domestic politics levels—that take more ambivalent and nuanced views of corruption (Fierascu Reference Fierascu2017; Johnston Reference Johnston2014; Mungiu-Pippidi Reference Mungiu-Pippidi2015; Rose-Ackerman and Palifka Reference Rose-Ackerman and Palifka2016). Although the general aspiration to fight corruption is normatively welcomed, the idea that political actors target rivals with corruption accusations seems plausible given anecdotal evidence—Indonesia included (Tomsa Reference Tomsa2015). After decades of neglect of the very idea of corruption, followed by a surge of research on how to curb corruption's effects on development, social scientists have begun to explore corruption dynamics in more nuanced ways (Rothstein and Varraich Reference Rothstein and Varraich2017; Sharman Reference Sharman2017).

We use Johnston's (Reference Johnston2005; Reference Johnston2014) “syndromes of corruption” framework as a departure point for our case. Johnson defines four types of “syndromes”—each one capturing distinctions in political power access, economic competition landscape, and institutional strength variations. First, influence markets emerge in established democracies with strong institutions and relatively open access to political voice. Coupled with highly competitive economic markets, corruption becomes a matter of securing privileged access to those in power—i.e., connections for “rent.” Second, elite cartels appear in countries with moderately strong institutions, growing economic competition, and increasing opportunities for political participation. As such elite networks use corruption to shore up their position against emerging rivals. Third, oligarch and clan corruption can be found in countries with weak institutions, a climate of poorly structured political competition, and a liberalizing market characterized with pervasive inequality. This leads to a scramble among contending elites to parlay resources into wealth and power. Last, official mogul corruption occurs in countries with weak institutions, little political liberalization, and a recently liberalized economic climate that is still fraught with extreme inequality and poverty.

Johnston characterized Indonesia as a case of official mogul corruption. Whether it should still be so characterized is not the point here. It is relevant, however, that in a follow-on study on the problem of reform, Johnston notes that in official mogul cases “most reforms accomplish little without the backing of top figures, for there are few independent political forces to demand accountability. Privatizations, high-level commissions, and intensified bureaucratic oversight can become the means of top-down political discipline, revenge against critics, or smokescreens for further abuses” (2014, 27). Our study builds on Johnston's insight about the problem of hollow reforms. We test hypotheses on the politicized use of corruption charges. By drawing on insights about party financing and coalition dynamics in Indonesia (Mietzner Reference Mietzner2015), we demonstrate the domestic obstacles to fully realizing the “good governance” agenda favored by international financial institutions but also central to domestic political legitimacy (Rothstein and Varraich Reference Rothstein and Varraich2017).

Still rare in the corruption literature is a systematic discussion about the strategic use of corruption accusations and prosecution. Corruption charges are inherently political. They are about which politicians get accused of what allegations; they are also about who is doing the charging—and with what success. In short, whether it is used to eliminate a rival or to rally a cause for protest, politicized corruption charges can undermine government efforts to comply with international institutions and its domestic promises to clean up. These observations should also impart some caution. Democratization alone cannot produce good governance (Rothstein and Varraich Reference Rothstein and Varraich2017): The duration of democratic institutions can affect both the extent of corruption (Rock Reference Rock2009) and how corruption plays out (Johnston Reference Johnston2014).

Corruption charges: Who and when

While mundane petty corruption (see Ang Reference Ang2020; Jap Reference Jap2021) is widespread in the Indonesian bureaucracy, our focus in this paper is on the major corruption charges levied against high-ranking government officials. These include cabinet-level ministers, national party leaders, politicians in the national legislature, and regional governors. They can also include civil servants working in central ministries that are involved in higher level resource allocation decisions. Our theoretical argument is specifically about when the government goes after these high-profile individuals—with empirical implications that it gets picked up by foreign media and garnering international attention.

Corruption charges are political not only because of who charges whom, but because of who charges whom when. Corruption charges can be handed out strategically when there are electoral benefits. Just as governments manipulate economic indicators before an election, we contend corruption charges also follow an electoral calendar. But unlike growth and employment (Nordhaus Reference Nordhaus1975), monetary flexibility (Clark and Hallerberg Reference Clark and Hallerberg2000), and tax-break policies (Chen and Zhang Reference Chen and Zhang2021)—or even caloric consumption (Blaydes Reference Blaydes2010)—more is not necessarily better when it comes to corruption charges. There are two reasons why.

First, too many corruption charges can be construed as a witch hunt. Romania's national anti-corruption division (Direcţia Naţională Anticorupţie) was aggressive with over 90 percent success rate in 2014. In 2015, it continued targeting high-profile politicians. After being indicted, PM Ponta attacked the chief prosecutor, noting her “obsession … to make a name by inventing and imagining facts and untrue situations from 10 years ago” (Gillet Reference Gillet2015). Too many charges can also be a sign of a government consolidating power. Since assuming power in December 2012, China's Xi has called for the “thorough cleanup” of the party. And while the anti-corruption messages have been packaged with economic reforms, it has not gone unnoticed by China specialists that the charges have been instrumental for strengthening his rule (Denyer Reference Denyer2013).

Second, and more importantly, there are differences between charging a fellow coalition member and an opposition member. Charging fellow coalition members—especially charismatic ones with strong followings—right after an election can undermine the coalition's integrity. This is particularly true in Indonesia where coalitions are often expanded post-election in what Slater and Simmons (Reference Slater and Simmons2013) refer to as “promiscuous power-sharing.” There is risk of defections and creation of rival parties. However, charging the same individual leading up to an election can remove a challenger from within the ranks. It decreases the risk of a sudden factional split—particularly if there are laws on party registration switching. Removing intra-coalition rivals also allows incumbents to fill vacancies with loyal allies. It is critical, however, that these allegations are not brought forth too close to an election. Doing so can undermine the party's reputation with its voting base and provide fodder for opposition parties—at a time when there is heightened attention directed on political events. Specifically:

H1: Major corruption charges against prominent government coalition members are more likely to happen before elections.

Conversely, charging opposition members before an election can come across as negative campaigning. Worse, the public can perceive the act as desperate if the charges are toothless and/or the incumbent is allegedly even more corrupt. Moreover, corruption cases require time to unfold. If the goal is to remove an opponent from the ballot, the electoral timeline is simply too short compared to that of the judiciary for this to be an effective strategy. Related, if the opposition were to win the election, there is no guarantee that they would not reciprocate and bring forth similar charges against the current government. Given this discussion, we argue when it comes to implicating the opposition, we are more likely to see charges early in the electoral calendar.

There are at least three advantages to this timing. First, it gives the case time to work its way through the judicial process—possibly damaging the concerned individual's reputation, thereby removing them from the political landscape for the long-term. Second, it affords the current government one less individual—whether in the cabinet, legislature, or governors’ council—to undermine and veto proposed legislation. And third, it allows the government to credit-claim and portray itself as going after graft. In summary:

H2: Major corruption charges against prominent opposition members are more likely to happen after elections.

If the incumbent is leveraging corruption charges strategically to remove challengers—from within and outside the coalition—there is no reason to believe that they would go after civil servants in the same way. This is not to say civil servants cannot be corrupt; there are cases of career bureaucrats engaging in graft. However, we are less likely to see charges brought against these individuals at politically opportune moments. Put differently, the probability of a corruption charge happening at any point in an electoral term is uniformly distributed, namely:

H3: Major corruption charges against civil servants are independent of electoral calendars.

Our argument rests on two premises. The first is that we can identify whether a charged politician is a member of the incumbent president's government coalition or the opposition. In Indonesia, individual loyalties and partisan affiliation are not always congruent (Slater and Simmons Reference Slater and Simmons2013). Thus, we consider any politician who has broken from an opposition party to publicly support the incumbent as a government member; and conversely, any politicians from an opposition who has not publicly broken from the party is considered opposition. Given the fluidity of Indonesia politics, we apply this definition and code at the time of the corruption charge. The second is that the executive incumbent has some power—even if indirectly—to effect when the charges are made. This is in fact the case in Indonesia. This influence can manifest through multiple channels. In the next section, we trace the timeline of a major corruption charge, calling attention to vulnerable points for politicization.

Timeline of Corruption Charges in Indonesia: Moments of Politicization

All corruption cases in Indonesia must prove that a criminal act includes elements “that can damage state finance and economy” (Supriyanto, Supanto, and Hartiwiningsih Reference Supriyanto and Hartiwiningsih2017). Thus, for any individual to be charged with corruption, there are two separate stages in the timeline. The first stage is the audit. In Indonesia there are only two agencies that can conduct the requisite audits (Nurmayani, Madinar, and Febbiazka Reference Nurmayani, Madinar and Febbiazka2020). The first agency, the Audit Board for the Republic of Indonesia (for Badan Pemeriska Keuangan Republik Indonesia, BPK RI), is the only external auditor of government finances (Musa Reference Musa2020). It has a constitutional mandate—per the fourth AmendmentFootnote 1—to audit state finances managed by the central government, the local governments, all state institutions, and all state-owned enterprises. Notably, its role is solely to audit, report, make recommendations, and monitor the implementation of recommendations. It does not bring charges if it finds irregularities. It does, however, task the requisite state officials with a set of recommendations for implementation. It also turns over evidence of wrongdoing to other agencies with prosecutorial power (Musa Reference Musa2020). The BPK RI is also required to submit audit results and report whether recommended tasks are being implemented to the House of Representatives (DPR), the Regional Representatives Council (DPD), or the Regional House of Representatives (DPRD)—depending on the target of the audit.Footnote 2

The second agency, the Finance and Development Supervisory Agency (BPKP), is a supervisory agency within the executive branch and reports to the President.Footnote 3 It conducts internal investigations and audits through the Supervisory Apparatus Internal Government (APIP) (Nurmayani, Madinar, and Febbiazka Reference Nurmayani, Madinar and Febbiazka2020). APIPs are supposed to ensure audits are done credibly by having a third-party evaluate the audit. Several studies, however, have found that the quality and independence of financial audits remain insufficient (Ahmed and Warsono Reference Ahmed and Warsono2020; Metalia, Zarkasyi, and Sugarman Reference Metalia, Zarkasyi and Sugarman2020; Muda and Erlina Reference Muda and Erlina2018; Winarsi, Nugraha, and Danmadiyah Reference Winarsi, Abrianto, Nugraha and Danmadiyah2020). While there is still debate over the legal authority of APIPs to calculate state losses (Nurmayani, Madinar, and Febbiazka Reference Nurmayani, Madinar and Febbiazka2020; Supriyanto, Supanto, and Hartiwiningsih Reference Supriyanto and Hartiwiningsih2017), they did do so for the corruption cases during the time of our data sample. During this period, they were weakly independent, and they reported to the relevant executive branch—i.e., the president for central government audits and bupati for local government audits.

The second stage is the prosecution. All corruption prosecutions must coordinate with one of these two agencies to prove their case in court. The legal requirement for state losses to be calculated and proved opens the door for politicization. In the case of APIPs, auditors work for the executive. The president can influence which numbers are hidden and which ones are not. And even in the case of the BPK RI, while the auditors are legally independent, they do not have prosecutorial authority. Instead, they must turn their audit findings over to the DPR, the relevant executive official/agency, and/or the relevant prosecutorial agency for further action. The fact that prosecutions have been delayed—and in fact, charges have been dropped—while defendants waited for the audit results is testament of the importance of this legal point. Supriyanto, Supanto, and Hartiwiningsih (Reference Supriyanto and Hartiwiningsih2017) write:

The Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi (KPK) efforts to process Deddy Kusdinar, AA Mallarangeng and Teuku Bagus Mohammad Noor as defendants on the level of prosecution is inhibited because the KPK is still awaiting the results of audit and calculation of state financial loss in the project. Not only the case of corruption at the national level, a number of handlings for corruption cases in the region is also inhibited because awaiting the results of audit or calculation of state finances losses.

In Indonesia, there are three agencies that can levy corruption charges. The Attorney General's Office (AGO) and the National Police are both under the auspices of the executive branch. These two offices were given the power to investigate and prosecute for corruption during Suharto's New Order regime (Butt Reference Butt2012). These agencies, however, were widely considered ineffective (Setiyono and McLeod Reference Setiyono and McLeod2010). Conversely, there is an independent Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Permberantasan Korupsi—KPK). The KPK was created during the post-Suharto Reformasi period as a centralized anti-corruption agency. The Commission has received substantial attention for its effectiveness (Butt Reference Butt2012; MacMillan Reference MacMillan2011). In the first seven years of its existence (2003–2010), the KPK had a 100 percent conviction rate. As a point of comparison, less than 0.05 percent of the three trillion rupiah lost to corruption in 1999–2000 was recovered by the AGO and the National Police (MacMillan Reference MacMillan2011). The KPK has the ability to take cases over from the AGO and the National Police if certain criteria were met—e.g., delays in handling complaints, conflicts of interest, and when a case's dismissal was questionable (Jacobs and Wagner Reference Jacobs and Wagner2007; MacMillan Reference MacMillan2011, 604). Moreover, the KPK was designed to operate externally from day-to-day politics. Every person charged would be brought to trial to avoid cases being dropped due to bribery (Butt Reference Butt2012).

Despite Indonesia's best efforts to insulate these institutions from politics (Hamilton-Hart Reference Hamilton-Hart2001), corruption charges in Indonesia can incorporate political elements. There are two possible reasons. First, even a nominally independent agency like the KPK must clear unofficial presidential veto points to bring charges against a public official. As discussed above, the KPK depends on the BPK RI or APIPs to calculate state losses—a key legal requirement needed for corruption charges to be filed. Early in its existence, strategic case selection by the KPK also allowed it to operate and tackle corruption—while avoiding (mostly) direct confrontation with those powerful enough to undermine their efforts with legislation (Butt Reference Butt2012).

Second, all three agencies have the power to investigate each other—and have done so. The AGO can dismiss KPK officials by charging them with corruption. Additionally, the National Police can charge KPK employees—translating into work suspensions during active corruption investigations (Butt Reference Butt2011). Consequently, KPK conviction rates dropped dramatically between February and October 2011 when more than 20 defendants were acquitted (Butt Reference Butt2011). The most famous example is the “gecko and crocodile” (cicak dan buaya) episode. It began when the National Police Chief of Detectives learned the KPK had tapped his phone during a corruption investigation. In response, he publicly warned that geckos (i.e., the KPK) should stay clear of crocodiles (i.e., the National Police). Moreover, he ordered two KPK officials arrested on extortion and bribery charges (Butt Reference Butt2012; Lim Reference Lim, Shah, Sneha and Chattapadhyay2015). While the charges were eventually dropped, this episode demonstrates how the KPK is not universally independent of domestic pressures and must make political calculations as well.Footnote 4

Research design

To test our hypotheses, we use an original, newly assembled dataset of all major corruption charges covered by the Associated Press in post-Suharto Reformasi Indonesia. The unit of analysis is year-month. We begin with June 1998—BJ Habibie's first full month as president; and we end in December 2015—the last full month before data collection efforts began (January 2016). Here we should note that Indonesia is a strong case for testing this theory. Three considerations motivated case selection.

The first was scope conditions. Corruption remains a problem in Indonesia to this day—“anti-corruption efforts in this setting will often be smokescreens for continued abuse of ways to put key competitors behind bars” (Johnston Reference Johnston2005, 45). While the institutional landscape did improve after Johnston wrote the book, many positive changes from that era have been rolled back (A'yun and Mudhoffir Reference A'yun and Mudhoffir2019; Ostwald, Tajima, and Samphantharak Reference Ostwald, Tajima and Samphantharak2016). Moreover, Indonesian country experts continue to demonstrate corruption charges—even those not covered by international media—contain political and electoral considerations (Tomsa Reference Tomsa2015).

The second consideration related to our dependent variable: major corruption charges. We see significant fluctuations over time. Moreover, there are substantial variations as to the political affiliation of the implicated individual—a necessary phenomenon to test our hypotheses. And finally, the third consideration was with respect to our independent variable: the electoral calendar. Indonesia has a presidential electoral system where elections are held at regular, fixed intervals. This ensures major corruption charges are in response to something exogeneous rather than an endogenously set election date.

Major corruption charges

To identify the population of major corruption charges, we use the Associated Press (AP). There were both push and pull factors with the choice of this news source. First, local Indonesian media is subject to elite-capture by well-connected oligarchs. Almost 97 percent of national television is owned by one of the few conglomerates (Winters Reference Winters2013, 25). Likewise, nine business groups control half of the print media in Indonesia (Haryanto Reference Haryanto, Sen and Hill2011). Consider how Tapsell (Reference Tapsell2015, 32) describes the media landscape:

While local news television stations exist, MetroTV and TVOne rate consistently higher in viewers than any local news station, and higher than the national government owned station, TVRI. ‘Oligarchic’ media includes TransCorp (owned by Chairul Tanjung), Visi Media Asia (owned by Aburizal Bakrie) Media Indonesia Group (owned by Surya Paloh), MNC Group (owned by Hary Tanoesoedibyo), Jawa Pos Group (owned by Dahlan Iskan), and Emtek's SCTV and Indosiar (owned by Eddy Kusnadi Sariaatmadja) … The problem of media concentration and ownership in Indonesia extends beyond television …. [It] has been exacerbated by increased conglomeration and platform convergence, with proprietors who previously only owned one platform (such as print, radio, or television) now building large, powerful multi-platform oligopolies.

The individuals named in parenthesis in this extract are all connected to high-profile politicians—if they are not one themselves. Even the most prominent English-language Indonesian newspaper, The Jakarta Post, is linked to Information Minister Ali Murtopo and career politician Jusuf Wanandi (Tarrant Reference Tarrant2008).

While concentrated ownership does not necessarily mean biased or incomplete reporting, there is evidence that local media engage in self-censorship (Tapsell Reference Tapsell2012; Tomsa Reference Tomsa2015), print stories in favor of their oligarchic owners (Mayasari, Darmayanti, and Riyanto Reference Mayasari, Darmayanti and Riyanto2013), and sensationalize corruption scandals as if they were plot devices in a soap opera (Kramer Reference Kramer2013). Even the widely-read and respected print media Kompas considers the impact of stories before they print them (Tapsell Reference Tapsell2012, 229).

Second, we use the AP given its global coverage and audience reach—making it the largest news source for scraping. Additionally, given its reputation for real time, reliable news, any corruption charge that makes the AP is by definition a major charge. The charge not only garners attention within Indonesia but regionally in Asia Pacific and globally as well. If the government is looking to use corruption charges for political gains, their coverage in an international source is testament to their high-profile nature.

One concern with the AP is its Jakarta-centric focus—risking the oversight of large parts of Indonesia. Empirically all but one of the charges in our data set involve cases that originate in the Jakarta area,Footnote 5 however, the majority of the cases (70 percent; 241 of 344) that get brought to the KPK also involve government actors in the greater Jakarta area (Tomsa Reference Tomsa2015). Moreover, when it comes to areas outside of Java, local journalists—working in resource-poor environments—often accept bribes from politicians to steer news coverage (Tomsa Reference Tomsa2015).

Third, while the charges covered by the AP are a small subset of the total number of charges in Indonesia over the time period covered by our sample, not all individuals charged are the same. If it seems everyone is being charged, it may be hard to ascertain which charges are being used politically to remove a challenger—whether in the government coalition or in the opposition. It is possible local news sources with connections to a high-profile individual would gloss over the reporting. The AP, however, would capture this. In short, the sample of reported charges by the AP reflect the class of high-profile, relevant politicians that warrant being targeted.

In short, given the concerns of partisan-affiliated reporting with the Indonesian newspapers and the empirical dominance of Jakarta in corruption-related news, we use the AP. Four individuals were involved with the newspaper scraping and data coding. They identified (1) who charged (2) whom (3) when (4) for what reason. The Cronbach's alpha between coders was 0.8276. In cases where there were disagreements, one of the authors made the executive decision. In all, we identified 59 cases of major corruption charges levied against a political figure.

With each article, we identify who is being charged with corruption and when. We also note the political affiliation of the individuals at the time the AP article was written. Since party affiliation can be misleading by itself—Indonesian governing coalitions often form independent of ideological dividing lines (Slater and Simmons Reference Slater and Simmons2013)—we consider an individual to be a government coalition member first if the news article mentions their personal connection to the president or vice president (e.g., family members or long-time associates) or if they are cabinet members. Given these connections are newsworthy, the AP often includes this information directly in the scraped articles. If there is no information about the personal connections, we then look to see whether their party backed the winning presidential ticket. We also consider a civil servant to be a government coalition member if they were arrested as part of a corruption investigation involving a coalition member. For example, President Yudhoyono (henceforth known as “SBY”) promoted many of his in-laws to high-ranking positions at Bank Indonesia, and they were subsequently implicated in a major corruption scandal. Several civil servants were arrested as part of the scandal. We considered these civil servants as part of the government coalition because news articles rarely failed to mention that their co-conspirators were connected to SBY.

Next, individuals are considered opposition members when they are personally connected to, or are themselves, a politician outside the government coalition. This includes individuals who have publicly identified with said parties in the past. For example, multiple bureaucrats who held high positions during Suharto's New Order were later charged during Presidents Habibie's, Gus Dur's, and Megawati's tenures. We considered these individuals Golkar members unless they publicly identified with another party. Finally, we code someone as a member of the civil service if they did not identify with a political party, never held a cabinet position, and were not co-conspirators in a scandal involving a politician. See Table 1 for the coalition codes for each implicated individual.

Table 1. Coalition codes for individuals charged

When coding for political affiliation, we looked for personal political connections mentioned in the news articles before defaulting to party identification. We do so because theoretically, politicians can cross party lines to join the government—and empirically, this happens regularly in Indonesian politics. Moreover, when political connections were present, news articles rarely failed to identify them. To understand why we weighted personal connections over official party identification, consider former vice president Jusuf Kalla. Kalla—famously a Golkar member—won the vice-presidency twice as the candidate running against his party's nominee. And after winning, on both occasions he brought personal allies—including Golkar members—into government positions. For example, in SBY's first term, a Golkar member close to Kalla was charged in a sports-related corruption scandal. When news articles talked about this Golkar politician, it was often about his closeness to Kalla as opposed to his partisan connection to the opposition. We are careful to document these cases of personal allegiance to ensure the political motivations are accurately captured in our analysis.

We should note that the corruption charges included in our dataset tend to focus on major scandals that included large bribes or steering contracts illegally to family, friends, and political allies. In Indonesia, these are known as Korupsi, Kolusi, dan Nepotisme (KKN)—i.e., corruption, collusion, and nepotism (Robertson-Snape Reference Robertson-Snape1999). These charges do not reflect the more common street-level corruption, which includes small payments by citizens (Olken and Barron Reference Olken and Barron2009).

We then collapsed the dataset—with its list of articles identifying the 59 instances of major corruption charges—into year-month units of analysis (N = 210). The dependent variable is the total number of individuals charged each month—disaggregated by political affiliation. As we see in Figure 1, the maximum number of individuals charged in any given month is three; this happened on one occasion. But in the majority of the year-months, there were no charges. Approximately 8.5 percent of year-month observations recorded a corruption charge.

Figure 1. Number of major corruption charges each month (Associated Press)

Electoral calendar

We code for—and take the logarithmic function of—both (1) number of months since the last presidential election and (2) number of months until the next one. We do this for several reasons. Theoretically, we expect the electoral effects to diminish as time increases. Changes between 11 and 12 months before/after an election should be more meaningful than changes between 23 and 24 months. Methodologically, transforming the independent variables using the logarithmic function ensures they are not perfectly colinear—thereby allowing both to be estimated simultaneously. This is key because the two (non-transformed) measures are correlated by construction. Running them in the same model would not be possible. Yet, estimating them separately would bias the coefficients—and thereby limiting our ability to test our hypotheses. Given our theoretical argument, we predict the following:

P1: The number of major corruption implications against prominent government members increases as the number of months until an election increases.

P2: The number of major corruption implications against prominent opposition members increases as the number of months since an election increases.

P3: The number of major corruption implications against civil servants does not change with respect to the electoral calendar.

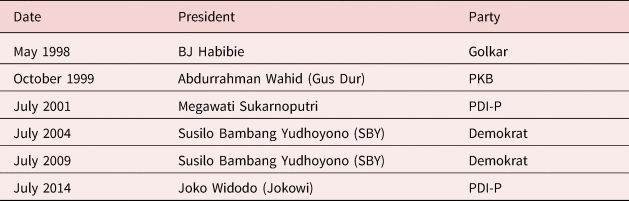

In our sample, we have five presidents. Habibie—one of Suharto's vice presidents—became president when his predecessor resigned on May 21, 1998. Habibie would subsequently lose the presidency to Gus Dur in October 1999. Gus Dur's tenure was short-lived: He was ousted in a no confidence vote in July 2001 and replaced by his vice president, Megawati. Since 2004, Indonesian presidents have been directly elected in a two-round system. Regardless of whether a second round is necessary, we code the first round as the election month. With the shift to direct election, Megawati would lose the presidency to SBY—who would go on to win his allotted two terms. And since July 2014, Jokowi has been the president of Indonesia. Table 2 lists the elections dates and the president.

Table 2. Presidents of Indonesia

Control variables

We consider other possible confounding effects. First, since there is a gap between elections and when the new president assumes office, it is possible that the outgoing president is a lame duck. We code for those months when there is an outgoing president. The number of months varies between each outgoing and incoming presidential pair. For example, while there was almost a one-month gap between Habibie and Gus Dur, there was none between Gus Dur and Megawati—courtesy of the no confidence vote (a campaign spearheaded by Megawati). And then between Megawati and SBY—when the electoral rules changed—there was again a one-month gap. And from SBY to Jokowi, while elections took place in July 2014, Jokowi was not inaugurated until late October. If there is any effect, we expect lame duck presidents—with few incentives to think about the long-term (Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán Reference Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán2015; Carter and Nordstrom Reference Carter and Nordstrom2017)—to implicate more opposition members for their final curtain call.

Second, there may be a TI effect (see Kelley and Simmons Reference Kelley and Simmons2020). Each year, TI issues a report with each country's corruption scores. The issue date varies annually; however, TI always announces beforehand the exact date that it will issue the report. While the report is a multi-month endeavor, we control for any last minute “corruption-cleaning” strategic behavior by the Indonesian government. Related, we also control for the month after the release of a report to capture any possible government response. Consider that there is a significant drop in Indonesia's score. If the report identified some transaction that the government was hitherto choosing to overlook, this could force the government—whether directly to get out ahead and shape public rhetoric or indirectly in response to popular pressures—to file corruption charges.

Finally, we include a lagged dependent variable. We do so for two opposite reasons. The first has to do with the clustered nature of corruption charges (see Figure 1). The same individual can be charged for multiple offenses. It is possible that an individual is charged for some crime in month m. But as the investigation continues into month m + 1, other related (but legally different) crimes come to light—forcing more charges to be filed. Related, one crime can involve multiple individuals. Instead of investigators uncovering more unique crimes in month m + 1, they identify more associated parties. This leads to more charges in the second month. A second reason—albeit with a different prediction—for controlling for last month's numbers has to do with a saturation effect. Charges do not just happen overnight; there has to be some credible evidence to suggest malfeasance. After someone has been charged in one period, it is likely that the docket is relatively empty. If this is the case, we would expect a negative effect—i.e., high levels of charges in one month lead to low levels in the next month.

Empirical evidence

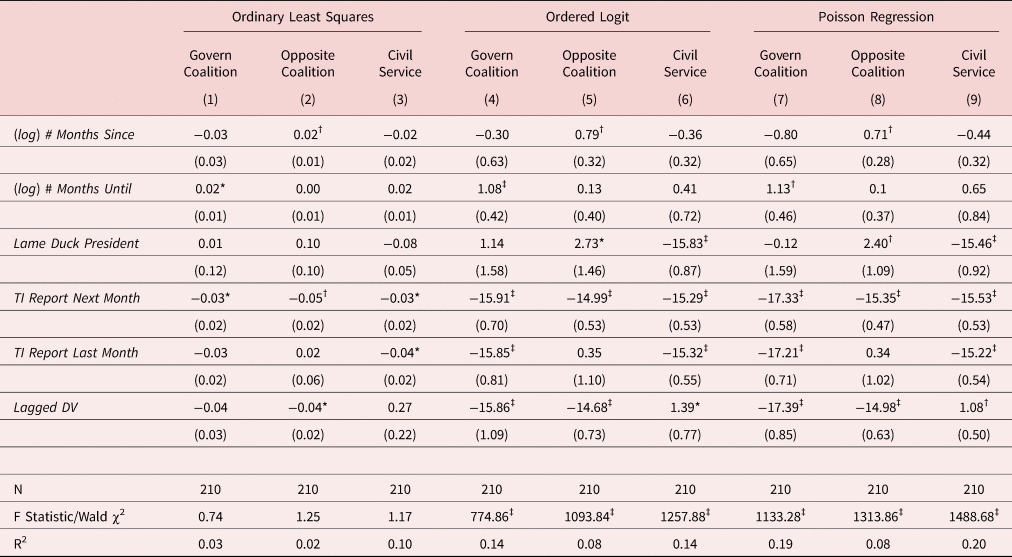

We estimate the models using ordinary least squares (given the theoretical distribution of the dependent variable—a continuous variable), ordered logit (given the discrete distribution), and Poisson regression (given the outcome is an event count). The results between the three sets of estimates are qualitatively the same (see Table 3). The first model in each set looks at the effect of the electoral calendar on the number of charges against government members. The second model is a replica of the first one, but with the dependent variable measuring the number of charges against opposition members. And the third model considers strictly civil servants. What we see is that each group is affected by government-manipulated electoral cycles in different ways (see Schultz Reference Schultz1995).

Table 3. Electoral cycles and number of major corruption charges

Note: * p < 0.10, † p < 0.05, ‡ p < 0.01.

Let us begin with the government members (models 1, 4, and 7). Consistent with our argument, individuals in the president's party or the government coalition are three times more likely to be charged leading up to an election (versus after an election). Note, however, that the charge cannot happen too close to the election. Charging an ally right before an election can undermine the party's popular support and the larger policy agenda (Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán Reference Camerlo and Pérez-Liñán2015); it can also be used by the opposition parties to challenge the president. But when major corruption charges are filed sufficiently early against a party member, the president can remove a disgruntled challenger or a difficult ally.

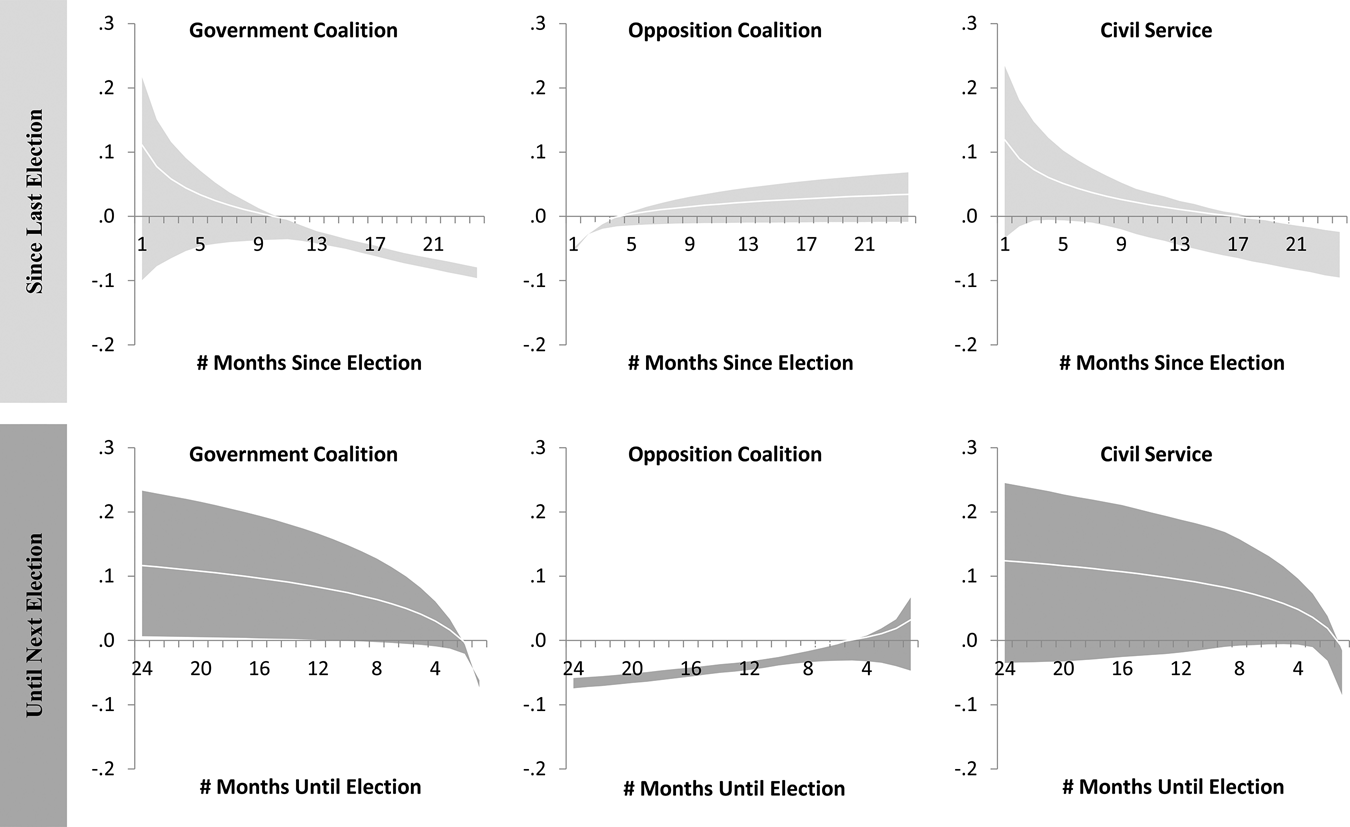

Electoral thresholds for executive branch candidates exacerbate this pattern. All candidates must be backed by a political party (coalition) whose vote share surpassed a threshold in the previous legislative election. Since negotiations between prospective candidates and parties occur leading up to future elections, corruption implications at this time can influence the party's decision of whom to back. Furthermore, as thresholds have increased over time (from 5% in 2004 to 25% in 2014), the number of available slots for any party has become scarce (Aspinall and Berenschot Reference Aspinall and Berenschot2019, 75). The results in Figure 2 (bottom left panel) shows how major corruption implication numbers against intra-party allies statistically increase as we approach an election. While the magnitude may seem small, recall that the modal number of major corruption implications in any year-month is 0. We only see major charges in about 8.5 percent of year-months. Moreover, this is the time period when candidates negotiate with parties for ballot access for the next election (Aspinall and Berenschot Reference Aspinall and Berenschot2019).

Figure 2. Number of major corruption charges vis-à-vis electoral calendar

We see this dynamic play out with Andi Alfian Mallarangeng, the former Youth and Sports Affairs Minister. His alleged involvement in a sports complex scandal had been a threat to President SBY's reputation as “Mr. Clean.” And while hundreds of people had been arrested during SBY's tenure, none were high-profile politicians (Karmini Reference Karmini2019). To this end, Mallarangeng's resignation would be the first for an active cabinet member. He was formally charged 10 months later—eight months before the 2014 presidential elections. Taking such action too close to the election risks dividing the party and losing supporters. But after the election has taken place, there is little incentive to go after a party member. While Mallarangeng was ultimately convicted, his prison sentence was far from harsh (Jakarta Post Reference Post and Desk2017).

During SBY's second term, Mallarangeng was not the only high-profile government coalition politician to be implicated. Party chairman Anas Urbaningrum and two additional ministers were also charged—mitigating any political influence they might have had within the party preparing for the 2014 elections. The charges surrounding Anas are illustrative: He used the siphoned funds not to enrich himself directly but to strengthen his own personal network within the party—as he looked towards a post-SBY future (Apsinall and Berenschot Reference Aspinall and Berenschot2019, 62).

Conversely, other high-profile individuals allegedly involved in corruption—but who were loyal to the president—were never implicated. For example, there were rumors surrounding SBY's son, but no charges were ever made. If presidents use corruption to remove potential intra-coalition challengers leading up to an election, consider who subsequently replaces these individuals. It behooves the president to replace the vacancies with loyal allies. It is worth pointing out that the candidate list for SBY's party in the 2014 legislative elections included 15 members of his family (Mietzner Reference Mietzner2014).

Note that it also only helps the president to charge high-profile members of their own coalition leading up to an election—but not right after one (see non-significant coefficients for (log) #Months Since). Removing an intra-party ally after winning an election can split the coalition, undermining the president's ability to pass legislation (see Figure 2—top right panel). Instead, the incentive is for the president to go after high-profile opposition members (see models 2, 5, and 8). Going after high-profile individuals affords the judicial process time to find the individual guilty—thereby removing them from the future electoral landscape. And while this plays out, it gives the president one less critical veto player when adopting policies. It also allows the government to credit-claim about cleaning up the country and paint the opposition party as rife with corruption. With each additional 18 months that pass, the number of charges filed against the opposition increases up to 0.04 (see Figure 2—top middle panel).

Consider the case of Rahardi Ramelan—the former head of the State Logistics Agency (Bulog) which manages the state's store of rice and other staples. In 2002—just a year after Megawati became president—Ramelan was convicted by the Megawati government for taking money from state welfare programs to fund Golkar campaigns (Crouch Reference Crouch2010, 210–211). This implication allowed the president to paint a high-profile politician from her principal rival party as someone who steals from the poor. Moreover, it cut off a source of campaign funds that could be used by political rivals for the next election.

The results also suggest that high-profile opposition members are no more likely to be charged leading up to an election (see Figure 2—bottom middle panel). This is consistent with our theoretical expectations: If the government goes after high-profile opposition members as elections are forthcoming, it can be construed by the public as negative campaigning—if not toothless. It can also be framed by the opposition as a witch hunt, particularly if the president is also corrupt.

Finally, we expected civil servants to be the most immune from the electoral calendar. The results confirm this: Neither (log) #Months Since nor (log) #Months Until is statistically significant in any of the models (3, 6, and 9). This is not to say that bureaucrats are not corrupt. In fact, paying for one's first civil service position is common practice, and the amounts paid are often much higher than the base salary alone (Blunt, Turner, and Lindroth Reference Blunt, Turner and Lindroth2012). Not surprisingly, civil servants constitute the plurality of corruption charges in our sample. However, what is of interest is the absence of a relationship between the implications in our dataset and the timing of the charges. If presidents were looking to shore up their anti-corruption credentials heading into an election, Indonesia has an ample supply of bureaucrats to investigate and charge. As we see in Figure 2 (top right and bottom right panels), the absence of this relationship suggests what matters is not that someone is implicated, but rather who is implicated.

We see evidence of other factors at play. First, when presidents are lame ducks, they are significantly less likely to target civil bureaucrats with major corruption charges. Instead, the focus of their charges is on opposition members. With a short horizon, they are more likely to follow through on their preferences (Carter and Nordstrom Reference Carter and Nordstrom2017)—including undermining their political rivals.

Second, across all models, it seems there is a TI effect. If the report is to be released in the next month, we see a decrease in the number of corruption implications—regardless of political affiliation. Likewise, in the month after a report, we also see a negative effect on major charges—but only for government members and civil servants. These effects suggest there may be some damage control—or the shaping of public opinion. Not implicating anyone high-profile during this period avoids calling additional attention to the matter.

Finally, it seems that there is a lagged effect. Recall, we predicted two possible mechanisms. The first is a clustered effect: The implication of one person for one crime can lead to more implications—whether it is the same individual with multiple crimes or multiple individuals for the same crime. We see this positive effect at play—but only for the civil servants. The second mechanism, however, is a saturation effect: After someone has been implicated in one month, it is likely that no new charges will be filed immediately in the next month. We see this play out for both government and opposition members.

Alternative explanation 1: Active presidents

When SBY was sworn in, he promised a “clean and good government” (Indonesian Presidential Library, October 20, 2004). With the KPK, we see a number of major corruption charges during SBY's time in office. One of the first—if not the most prominent—case involved Abdullah Puteh. Puteh was the then-Aceh Governor. In December 2004, he was charged with siphoning state funds and padding the price tag to purchase two MI-2 Rostov helicopters. In April 2005, the court found him guilty and sentenced him to 10 years (Sulaiman and Van Klinken Reference Sulaiman, Van Klinken, Nordholt and Klinken2007). This example highlights the possibility that the observed patterns for corruption charges mirror not the electoral calendar in general, but the tenure of specific presidents.

To consider this, we rerun the three baseline models from Table 3—but with president fixed effects and clustered standard errors by president. Including presidential fixed effects allows us to also pick up temporal effects if voter preferences toward corruption changes over time. The reference category is Habibie—the first president. The results can be found in Table 4 (models 1, 2, and 3). We see that even when considering individual presidents, the effects for the electoral calendar variables remain unchanged. While the coefficient for (log) #Months Since is now significant in the government coalition sample (model 1), it is correctly signed as how theoretical priors would suggest: negative. Moreover, the coefficient for (log) #Months Until remains significant and positive (β=0.03; SE = 0.01). Likewise, charges against opposition members tend to fall earlier in the electoral calendar (model 2).

Table 4. Alternative explanations: Active presidents and active anti-graft commissions

Note: * p < 0.10, † p < 0.05, ‡ p < 0.01. 1 Reference Category = President: Habibie.

The results also confirm that there were more corruption charges during SBY's tenure. SBY was more likely than any other Indonesian president to charge members of the state bureaucracy (β=0.09; SE = 0.02). He was also more likely to go after those in his own governing coalition (β=0.07; SE = 0.03). The aforementioned case of Andi Alfian Mallarangeng, his former Youth and Sports Affairs Minister, is an example of this. And finally, SBY was also more likely to go after those in the opposition (β=0.02; SE = 0.01)—e.g., the case of Aceh Governor Abdullah Puteh and his two MI-2 Rostov helicopters.

Interestingly, we see similar numbers for Megawati. She was proactive going after those in her own party or cabinet (β=0.07; SE = 0.03) and those in the opposition (β=0.02; SE = 0.00). These numbers are statistically no different from SBY's. Where we do see a difference is with respect to those in the civil service (β=0.05; SE = 0.03). This suggests that while SBY may have campaigned on a transparency platform and was active with anti-corruption legislation, he was not necessarily that distinct from Megawati.

The results in Table 4 also suggest that—when including presidential fixed effects—we see a similar pattern for government coalition members (β=0.03; SE = 0.02) and civil servants (β=0.02; SE = 0.00). One explanation for this finding is that the executive may use the charging of civil servants leading up to an election as a way to signal they are cracking down on corruption—without the resulting blowback. Alternatively, it may be a way to create a vacancy for a more like-minded civil servant. Regardless, we hesitate to read too much into this finding as this result is sensitive to model specifications. In short, it seems that even when we control for individual presidents, electoral calendars still have an independent effect on who charges whom—when.

Alternative explanation 2: Active anti-graft commissions

Another explanation is that these major corruption charges are the product of active anti-graft commissions. Just as courts can strategically use the media to strengthen judicial power (Staton Reference Staton2010), an institution aiming to clean a country up can use elections to remove corrupt individuals. There are reasons to believe Indonesia's anti-corruption agencies are not necessarily apolitical bystanders.

To test the possibility of an active anti-graft judiciary, we employ a two-prong approach. First, we shift the focus from corruption charges to major corruption convictions. If the anti-graft bodies are genuinely interested in transparency, what matters is not the number of individuals charged but the number found guilty. We scrape for all news articles with mentions of major corruption convictions in the AP (N = 29) and then again, we collapse the sample into year-month units of analysis. Our dependent variable is the number of individuals convicted each month. The modal number of convictions in these major corruption cases is zero, but we do see as many as four convictions (September 2005). As before, we also identify the political affiliation of each convicted individual—i.e., whether they are members of the government coalition; whether they are opposition members; or whether they are no public affiliation with any party. The results can be found in Table 4.

Model 4 looks at the number of convictions for those in the president's party or the cabinet each month. Given these results, we have no reason to believe the judiciary is responding to an electoral timeline. Neither variable of interest has an effect distinguishable from 0. In fact, the entire model is not statistically significant! The substantive results change little even when we shift the political affiliation to opposition members (model 5) or those in the civil service (model 6). Again, there is no evidence of an electoral calendar. Not only are the two coefficients not significant, but their magnitudes are also 0.

Our second approach is to focus on all of its activities in a given month. In this case, we consider not just charges and convictions, but also appeals in major cases. Empirically, the court has both upheld and reversed rulings. Again, we collect all news articles from the AP pertaining to appeals in major cases and identifying whether the individual involved with the appeal is a member of the government coalition, the opposition coalition, or the state bureaucracy. We then collapse the sample into year-month units of analysis. We take the number of appeals per month in major cases and add them to the number of charges and convictions in that month as well for a measure of all activities. The results can be found Table 4.

As with the conviction models, neither coefficient of interest ((log) #Months Since and (log) #Months Until) is significant in any of the three models (7, 8, and 9). Taken together, these null findings suggest two related implications. First, if the court is acting strategically when it comes to major corruption cases, its behavior is not being motivated by the electoral calendar. Second, the fact that we have found evidence of an electoral effect only for major corruption charges—the first and easiest step in the process—suggests governments are employing such tactics politically. But whether these charges actually have any teeth and amount to a conviction is a different story.

An illustrative case: Setya Novanto

To illustrate the strategic use of high-profile corruption charges to remove an intra-party ally—against the fluidity of Indonesian politics—consider the case of Setya Novanto, former Golkar head and leader of Indonesia's House of Representatives (DPR). When Jokowi took power in late October 2014, his coalition did not have the requisite number of seats in the DPR. This is not an uncommon situation given Indonesia's ballot access thresholds and restrictions on party-switching (Aspinall and Berenschot Reference Aspinall and Berenschot2019); thus, Jokowi needed to expand his coalition. He opted not to concede ministerial portfolios to political rivals. Doing so would have given them control over public resources that could then be used to build rival political networks (as occurred during his predecessor's tenure).

As an alternative, Jokowi used a law that allowed him to intervene in the internal affairs of political parties. This law gave Jokowi the authority to recognize the “official representative” of each political party in the government. And with this law, he afforded recognition to individuals more sympathetic to his politics, specifically within parties that opposed him (Warburton Reference Warburton2016). For Golkar, the implications were substantive: Chairman Aburizal Bakrie was replaced by the Jokowi-backed Setya Novanto. With Setya as the new party chairman, Golkar switched its support to Jokowi—thereby giving the president majority support in the DPR.

In late 2015 Setya's involvement in a large mining contract scandal became public, and the AGO subsequently opened an investigation (Amindoni Reference Amindoni2015). The AGO investigation, however, never led to charges. As Jokowi's ally—albeit an ally of convenience—he was protected by the president. Additionally, the active investigation incentivized Setya to stay in good standing with Jokowi, essentially acting as an insurance policy for the president.

Despite the AGO's inaction, the KPK opened a parallel investigation. The KPK, however, did not press formal charges until October 2017, approximately two years later (Almanar Reference Almanar2017). The timing of these charges is notable: By late 2017, there were once again divisions within Golkar, and the party's continued support of Jokowi became less certain (Soeriaatmadja Reference Soeriaatmadja2017). With the KPK charges, Setya no longer had any incentives to remain loyal to Jokowi, and although he failed, he attempted to appoint a successor from the anti-Jokowi faction of the party (Cook Reference Cook2017). Likewise, with Golkar's continued support in doubt, Jokowi no longer had any incentives to protect Setya from the KPK—resulting in the latter being officially charged.

Consistent with our empirical findings, formal charges against Setya were brought in late 2017—when party members were internally jockeying for slots in the next election (Aspinall and Berenschot Reference Aspinall and Berenschot2019). This was a period far enough from the election itself to impact which candidates would remain. Those deemed non-loyal—e.g., Setya by this point—were more likely to be charged and removed. And those considered loyal were tapped to fill the vacancies. We see the mechanism at play as Jokowi won reelection with Golkar support in 2019.

Conclusion

In this article we theoretically contend and empirically demonstrate that major corruption charges are not only political because of who charges whom but also when. Specifically, major corruption charges against members of the government coalition in national politics in Indonesia are more likely to happen before an election, allowing the government to remove intra-party rivals and consolidate support. Conversely, major corruption charges against those in the opposition coalition are more likely to happen after an election when fears of retaliation are low and the opportunities for credit-claiming are high. Together, these results yield insights into how anti-corruption efforts can become a political tool for incumbent presidents. They serve as a corrective to overly optimistic or technocratic assumptions about the effectiveness of “good governance” agendas emanating from IFIs or aid agencies. Instead, they support arguments counseling caution about the role of democratization in curbing corruption (Johnston Reference Johnston2014; Mietzner Reference Mietzner2015; Rock Reference Rock2009).

Our current analyses rely on AP news articles. The use of this particular source may have skewed the attention away from local political stories toward those high-profile cases important to Jakarta specifically and the international community broadly. Media reports on governors, mayors, or provincial legislators outside Indonesia's largest cities may be overlooked despite the fact that many of tomorrow's high-profile politicians start in these lower, peripheral offices. Yet, there is evidence to support our Jakarta-centric data: Approximately 70 percent of the corruption implications in our dataset were initiated by the KPK. To see why, it is important to recall two points. First, according to Schutte (Reference Schutte2012), KPK makes less than 5 percent of all corruption charges in Indonesia (in stark contrast to the AGO and the National Police). Second, the KPK is seen as the most competent and politically independent of the three concerned government agencies. This belief originates from it having the highest conviction rate (for corruption cases) and it being the one government agency whose head is not appointed by the president. Given this, we should find null results on our electoral cycle variables. Yet we find significant results instead. The fact that we still find evidence of electoral cycles in major corruption charges—when the odds were biased against us—suggests our results could be even more pronounced if we expanded our dataset to be more representative of Indonesian news media, especially outside of the Jakarta area.

The results suggest several possible avenues for future research. The first is to scrape the major national newspapers—knowing that they are all linked to politically-influential individuals—for articles about these corruption charges. With this corpus, we could then do a sentiment analysis—i.e., how do these sources cover the charges, if at all. The second is to consider the central–periphery dynamics. Tomsa's (Reference Tomsa2015) research on the politicization of corruption in the outer islands provided evidence that bupatis leverage relationships with DPR members from their home regions to shield themselves from corruption charges. An extension would consider the relationships between Jakarta-based politicians and allies in their home regions. The third would be to scrape regional newspapers to generate a dataset with more instances of low-level corruption to determine whether those types of corruption charges produce similar findings or whether our results are peculiarities of national-level coalition building in in Indonesia (Slater and Simmons Reference Slater and Simmons2013). And fourth, future research could explore the patterns for civil servants in the fixed effects regression—where results mirrored the government coalition results. This would help elucidate whether the results were a statistical anomaly or a clue to a more nuanced understanding of how mundane corruption charges can be politicized.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2016 International Studies Association's Annual Convention (Atlanta, GA) and at a workshop at University of Colorado Boulder. We thank Stephen Haggard and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We are also grateful to Adriana Cerda, Christiana Segura, and Garrett Thompson for their help with the data collection. All errors remain our own.

Any views, findings, or opinions expressed in this work are those of the authors and not those of the U.S. Department of Labor or the United States Government.