Introduction

Patients with poorly controlled multiple chronic conditions (MCCs) often have unhealthy behaviors, poor mental health, and unmet social needs which can complicate outpatient management. One approach to addressing these root causes is for patients to create health-related goals and care plans and then get help from a care team to achieve their goals [Reference Glasgow, Davis, Funnell and Beck1]. Patient-centered care planning first involves assessing patient health risks and identifying which needs to prioritize [Reference Miller2]. Patients then define a personal goal and select strategies for achieving it. Previous studies demonstrate that disease-specific care plans can improve management of conditions and quality of life [Reference Khalifehzadeh-Esfahani, Amirzadeh and Golshahi3,Reference Mikkola, Hagnäs, Hartsenko, Kaila and Winell4].

Care planning can be difficult for patients to complete without guidance and is time-consuming for clinicians, but digital health tools can help facilitate this process [Reference Glasgow, Huebschmann, Krist and Degruy5]. We are thus expanding the previously tested web-based screening tool My Own Health Report (MOHR) [Reference Krist, Glenn and Glasgow6], to support patients in creating care plans for health behaviors, mental health, and social needs. MOHR was developed to assess these risks, but did not include a formal care planning process. This expansion is a part of a larger trial testing a community strategy to address root causes of uncontrolled MCCs, which involves using patient navigators, community health workers, and clinical-community linkages to help patients achieve personal care plan goals.

Creating a care planning tool that is patient-centered, evidence-based, and promotes shared decision-making regarding multiple health risk factors is difficult. Authentic engagement of stakeholder groups can be used while creating a health intervention in order to enhance its adoption and implementation [Reference Kilbourne, Goodrich, Miake-Lye, Braganza and Bowersox7–Reference Woolf, Zimmerman, Haley and Krist9]. Recent guidance for researchers on best practices for health intervention development includes recommendations to engage relevant groups throughout the process [Reference O’Cathain, Croot and Duncan10]. However, stakeholders are often not included in intervention development processes and there is a lack of information about the engagement process and outcomes when stakeholders are included [Reference Majid, Kim, Cako and Gagliardi11]. Therefore, there is a need for examples in the literature of researchers meaningfully engaging stakeholder groups and the impact created by their involvement.

We solicited feedback from four diverse stakeholder groups to inform the design, use, and impact of MOHR’s expansion. These groups included community members, academic researchers, community service professionals (CSP), and patients. This paper reports on the feedback received from each stakeholder group, how it shaped the tool’s final form, and implications for researchers doing similar work.

Methods

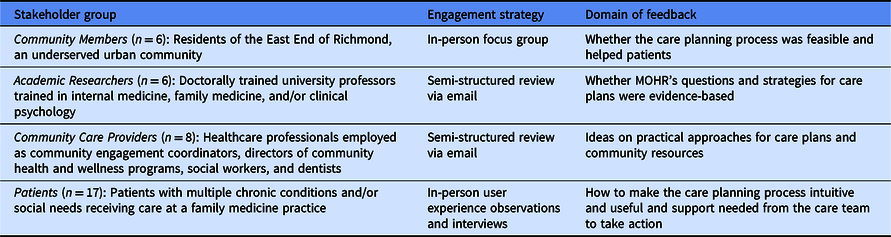

Using a qualitative approach, this study sought and evaluated feedback from four stakeholder groups to inform the design of a web-based care planning tool. As summarized in Table 1, the research team engaged each group separately using a focus group, structured feedback, or semi-structured interviews. Throughout the process, stakeholders were asked to consider the MOHR care planning concept, content, understandability, feasibility, and/or usability. This study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board (IRB HM20015553) and conducted between November 2019 and August 2020.

Table 1. Major domains of stakeholder influence on my own health report care planning design

Community Member Engagement

Six community members (83% female) were recruited from an existing community partnership, Engaging Richmond, which serves the disadvantaged, urban, East End of Richmond, Virginia [Reference Woolf, Zimmerman, Haley and Krist9,Reference Zimmerman, Haley and Creighton12]. Feedback was solicited through a focus group facilitated by two members of the research team. Facilitators demonstrated the MOHR online tool content and prompted feedback on appearance, usability, goal creation workflow, strategies to achieve goals, and the roles of patient navigators and community health workers. The focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed.

Academic Researcher and CSP Engagement

Six academic clinicians and researchers (33% female) participated who were involved in the larger study as content experts in chronic disease, behavior change, and/or community-oriented primary care. All had doctorate-level training in internal medicine, family medicine, or clinical psychology. Nine CSP (89% female) caring for patients’ health-related needs in the community were recruited. CSP participants included community engagement coordinators, directors of community health and wellness, social workers, and dentists. Feedback from both groups was collected via semi-structured email questions asking participants to review MOHR’s content for evidence supporting the tool, feedback on wording, missing content, and content to remove.

Patient Engagement

A convenience sample of seventeen patients (41% female) was recruited from two primary care practices, in Richmond and Fairfax, Virginia. Clinicians identified patients with MCCs who might benefit from using a tool like MOHR. In-person user experience observations and semi-structured interviews were conducted with each patient. Patients navigated MOHR and were prompted for their reactions to the health risk assessment, deciding which topic(s) to address with a care plan, picking a personal goal, selecting strategies, and navigating the system. Patient interactions were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Analysis

Transcripts and written feedback from stakeholder engagement activities were subjected to qualitative content analysis using template and emergent coding processes [Reference Bernard, Wutich and Ryan13]. Template-based codes were derived from the literature on health behavior change, user experience, and health information technology. Themes related to the patient-centered care planning processes; digital interface design, usability, and functionality; clinical content accuracy and coherence; and implementation feasibility. We used Microsoft Excel to organize, store, and code the qualitative data. Three authors (KO, AH, HS) coded independently and then met to review themes and resolve discrepancies.

Results

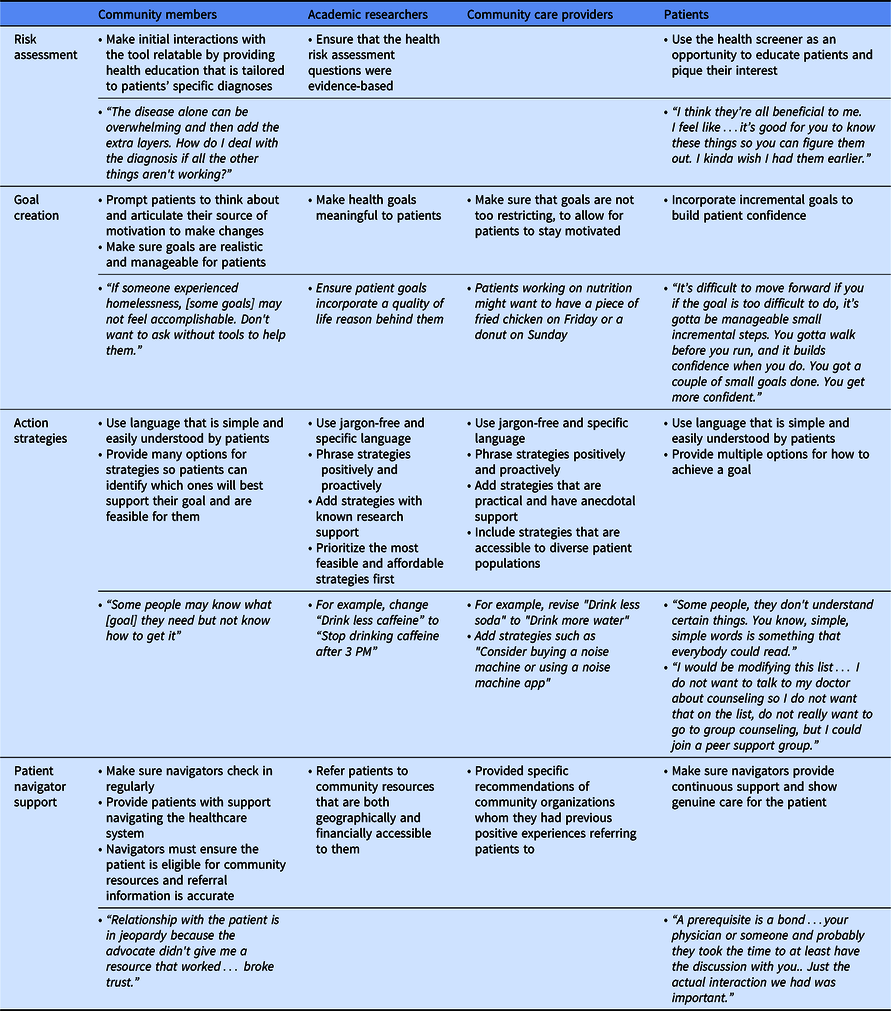

The four stakeholder groups brought unique perspectives to MOHR’s key features for care plan development, as summarized in Table 2. Both community members and patients highlighted the importance of manageable goals and ongoing support. Community members also focused on the patient navigator relationship and need for accurate and reliable community referrals. Patients recommended patient health education and access to care plan examples. Academics and CSPs both suggested using action-oriented language. Academics prioritized recommendations with an evidence base, while CSPs focused on recommendations with anecdotal support from clinical experience.

Table 2. Key stakeholder feedback informing key features of the care planning process and MOHR design

Three groups reacted to MOHR’s risk assessment component. Community members wanted the health risk assessment process to educate patients on the connection between health condition management and behavioral, emotional, and social factors. Similarly, patients were often surprised by the relation between risk factors and their physical health. They expressed appreciation for learning how these factors influenced their health, with one patient stating, “I kinda wish I had this earlier.” Finally, the academic researchers focused on ensuring that the questions included in the health risk assessment were evidence-based.

All groups commented on goal creation in MOHR. First, community members suggested clarifying personal sources of motivation and anticipated benefits. Community members and patients discussed the need for ensuring that goals are realistic, voicing concern that patients with unattainable goals may become discouraged. Academic researchers suggested that patients consider ways to meaningfully improve their quality of life when creating goals, in order to enhance patient motivation and commitment. Specifically, tying the goal to a desired outcome, such as, “complete daily exercises to build strength and be able to play with my grandchildren.”

Community care providers cautioned against making goals that are too restrictive, suggesting that incorporating flexibility would keep patients engaged. For instance, a patient working on nutrition may want to eat a “treat” every so often. Patients suggested starting with their smaller goals to allow for patients to build self-efficacy before addressing larger goals.

All four groups provided recommendations for MOHR action strategies. Each group recommended removing jargon and improving language specificity. This was not limited to medical terminology, as they expressed a general preference for using words accessible to those at lower reading levels. They identified phrases to improve specificity, such as revising “improve sleep environment” to include specific strategies, such as the use of sound machines or sleep-aid apps. Both academic and CSP participants preferred strategies framed positively and proactively. For example, they suggested replacing “stop eating unhealthy snacks” with “replace processed snacks with those that are high in protein, low-fat, or fresh.” CSP participants recommended new strategies with anecdotal support, regardless of research support. For example, they suggested adding strategies such as “sleep with a white noise machine.” Conversely, academics suggested adding only strategies with research support. Academic researchers also stated the tool’s organization of action strategies was paramount for patient comprehension of the topics. They proposed headers for each section of patient strategies to enhance quick understanding of the information. Community members and patients wanted multiple examples of action strategies to choose from while creating their care plan to pick ones best suited for their lifestyle and goals.

All four groups had suggestions related to the patient navigator role which supports patients throughout the care planning process. Community members and patients indicated that providing ongoing support outside of the tool was necessary, highlighting the importance of the patient navigator relationship. They preferred that patient navigators initiate regular check-ins and be easily accessible for ad hoc support, when needed. Patient participants suggested including contact information for patient navigators in the tool so that patients can reach out for help directly. Community members also recommended verifying resources before making a referral to community resources, reporting that referrals pose risk of damaging patient trust when referral information is inaccurate or contacts are difficult to reach. Academics identified potential patient barriers with community resources, advising patient navigators to provide referrals that are geographically and financially accessible. CSP participants provided specific recommendations of “trusted” community organizations they had past positive experiences with.

Discussion

This report summarizes an efficient procedure for eliciting important input from four key stakeholder groups and how it informed the development of a web-based care planning process and platform. Across groups, there were both unique and shared recommendations, that together should improve the functionality and use of our tool and support program. Recommendations ranged from simple language alterations that made the tool more patient-friendly to describing meaningful ways for patient navigators to support patients and to promote patient care planning success.

Health services research and the healthcare industry commonly seek user feedback to improve research aims or products. Health risk screeners and decision aid tools must undergo rigorous validity and user testing, which relies on clinician, patient, and public engagement [Reference Akl, Grant, Guyatt, Montori and Schünemann14,Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams15]. Patient and public engagement has also been used for developing health IT, such as health screening web pages, mobile health records, and patient information sharing platforms [Reference Krist, Glenn and Glasgow6,Reference Perfetto, Harris, Mullins and dosReis16]. Meaningful engagement throughout development results in broadening the “reach” of a product, by ensuring that patients are better able to use and navigate it. Engaging patients, clinicians, or a community has been shown to improve patient experiences and desired outcomes. However, the singular engagement of each group is insufficient on its own. Our findings highlight the benefits of blending perspectives from multiple groups and how they contributed to the development of a more practical, actionable, and helpful care planning tool.

A limitation of this study is the timing and method of feedback. Feedback from each group was solicited at different stages of development. The stage of development was, importantly, pertinent for the domain of feedback they provided (i.e., patient feedback was not sought until after the tool had been developed in a mature, usable form rather than conceptual.) We also solicited feedback using various methods across groups; the type of feedback method was purposefully selected to promote what we considered the most thoughtful feedback from each group.

Conclusion

Our approach with multiple stakeholder engagement offers insight for researchers and healthcare providers designing similar interventions. It is imperative to solicit and incorporate feedback from a range of stakeholders to develop interventions that are more practical, actionable, and helpful. As demonstrated here, the participation of community members, researchers, community care providers, and patients throughout development provided important complementary perspectives to develop a robust care planning tool.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Fairfax Family Practice Center and the Nelson Family Medicine clinic for assistance in identifying patient stakeholders for participation; Engaging Richmond (Chimere Miles and Leah Gregory) for assistance in identifying community member stakeholders for participation; the YMCA of Richmond (Jana Smith and William Thornton), VCU Dentistry (Sarah Raskin, Tegwyn Brickhouse), as well as Sherrell Johnson, Stephanie Toney, Neci Hill, Patty Whanger, and Shanta Bland for their support and community perspective; the members of the Enhanced Care Project Steering Committee (Steven Woolf, Jim Mold, Winston Liaw, Bruce Rybarczyk) for their academic perspective.

Funding for this study is provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1R01HS026223-01) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (ULTR002649). The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.