Introduction

Clinicians interested in conducting clinical research face numerous obstacles to gaining the foundational training to support high-quality research. Medical school strongly emphasizes developing the students’ clinical practice abilities, leaving little time for research [Reference Mullikin, Bakken and Betz1]. Traditionally, aspiring clinician-investigators have received on-the-job training, sometimes by serving as a subinvestigator or through mentorship [Reference Saleh and Naik2,Reference Bonham, Califf, Gallin and Lauer3]. However, over time the scope of principal investigator (PI) responsibilities has expanded [Reference Saleh and Naik2]. PIs need to manage complex federal and local regulatory requirements, ensure ethical study conduct and participant safety, communicate well with research participants, and lead and manage diverse research teams, among other duties [Reference Bonham, Califf, Gallin and Lauer3]. The increasing demands of being a PI have necessitated additional training for clinician-investigators.

Numerous trainings exist to help fill this gap. For instance, the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Program, sponsored by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, offers two types of awards for clinical research training. First, the KL2 Mentored Clinical Research Scholar program provides up to five years of support for junior faculty holding an M.D., Ph.D., or equivalent degree to pursue research training. Second, the TL1 Clinical Research Training Award provides full-time research training for students (including predoctoral, doctorate/master’s, and postdoctoral candidates). While the KL2 and TL1 programs offer valuable opportunities for junior faculty and students to develop their research skills, these awards can only be given to a select number of applicants each year [4]. Professional certifications in clinical research, including certifications from the Association of Clinical Research Professionals and the Society for Clinical Research Associates, also can provide investigators with additional training [Reference Getz, Brown, Stergiopoulos and Beltre5–7]. However, these certifications require 1–2 years of previous clinical research experience. Scholar programs and professional certifications alike require a significant investment of time and are better suited for clinicians who are confident they want to pursue research long term.

On the other hand, there is an abundance of less comprehensive but more accessible training opportunities. In a recent update to a standardized set of core clinical trial competencies, working groups identified 219 unique trainings across CTSAs, professional organizations, industry, and government addressing at least one competency [Reference Calvin-Naylor, Jones and Wartak8]. While these trainings included free-of-cost and online offerings, they often lacked active learner engagement, the opportunity to practice applying new skills, and details about local research procedures [Reference Calvin-Naylor, Jones and Wartak8]. Due to these gaps, participation may be ineffective as learners are not gaining access to the information and skills they need to conduct research at their site.

Diversifying the clinical research workforce is critical in order to build trust with research participants, bolster participant recruitment, and better address health disparities [Reference Bonham, Califf, Gallin and Lauer3]. However, diversity efforts may be hampered for a number of reasons. Aspiring clinician-investigators are sometimes required to make difficult trade-offs between time spent on clinical duties, with family, and on research [Reference Loucks, Harvey and Lee-Chavarria9]. Unsurprisingly, burnout and turnover occur frequently among clinician-investigators and many investigators drop out of clinical research each year [Reference Getz, Brown, Stergiopoulos and Beltre5]. Furthermore, among early career research trainees, women and underrepresented minorities are more likely to report experiencing burnout.[Reference Primack, Dilmore and Switzer10]

Given the limitations to current education opportunities and the need for clinician-investigators to balance research with work and life demands, it is evident that we need another model for training this segment of the clinical research workforce. CTSA institutions, as well as academic health centers, are uniquely poised to address these training needs, since both entities advance scientific discovery from bench to bedside and provide continuing educational opportunities to the clinical research workforce [Reference Bonham, Califf, Gallin and Lauer3,Reference Moskowitz and Thompson11]. Furthermore, the CTSA Program is committed to cultivating diversity in the clinical and translational science workforce [12,13].

In 2017, the CTSA Consortium Enhancing Clinical Research Professionals’ Training and Qualification project focused on standardizing clinical research competencies within the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency framework. The goal of this project was to improve trainings for clinical research coordinators and PIs, and, in turn, improve clinical trial efficiency [Reference Calvin-Naylor, Jones and Wartak8]. Since then, CTSA institutions have described trainings connected to framework domains and competencies. This has included a clinical research coordinator (CRC) training that was successfully adapted from one CTSA institution, the Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science, to two others at Penn State University College of Medicine and the University of Mississippi Medical Center; across the two implementing sites, participants experienced improvements in knowledge and confidence with carrying out research responsibilities [Reference Musshafen, Poger and Simmons14]. To address gaps in investigator training, faculty and staff at the University of Alabama at Birmingham implemented a research training program for young physicians that included lectures, group projects, panel discussions, and mentoring components [Reference Saleh, Naik and Jester15]. The authors reported that this program was successful in increasing the number of participants who went on to attain PI status following participation.

Staff at our CTSA institution recognized a need for a continuing education program to support clinicians interested in conducting clinical trials in order to advance the local workforce. In response, we aimed to design a sufficiently rigorous training program spotlighting local practices and research support services, yet still amenable to the scheduling needs and work burdens faced by clinicians. We implemented the Blue Star Investigator Certificate Program at Tufts Medical Center in 2021. We hypothesized that this training would be manageable for clinician-learners, while also giving them the knowledge and skills to pursue becoming a clinical trial PI.

Program Development

In August 2020, the curriculum development team began formulating a pilot module that was delivered to eight learners in January 2021. This module was composed of one hour of asynchronous online prework material covering the fundamentals of study budgets and writing letters of intent, followed by a two-hour live online session where participants worked in groups to create a study budget. In addition, a content expert in industry-sponsored trials joined to discuss how sponsors make funding decisions.

Feedback and lessons learned from the pilot module were crucial to informing the development of the overall Blue Star curriculum. For instance, we realized it would be more intuitive to start with protocols, instead of letters of intent, for an audience of junior faculty. In addition, while learners were actively engaged during the live session, we found that discussion was somewhat hindered by the online format; for this reason, we decided to conduct as much of the Blue Star curriculum as possible in-person. The planning team incorporated their own reflections and participant feedback from the pilot module and, in collaboration with content experts, began to design eight modules that would become the Blue Star training program curriculum.

The training program was led by two faculty members with expertise in regulatory review and the design and conduct of clinical research. The curriculum development team was composed of CTSA staff with expertise in education development and communication, project management, and research process improvement. Each module included content experts who served as consultants for prework material as well as guest speakers during live sessions. Content experts spanned staff from across Tufts CTSI, as well as staff from Research Administration, Compliance, and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) from Tufts Medical Center, and staff with expertise in team science from Tufts University. In total, twenty content experts provided input and delivered program components.

Fall 2021 Curriculum

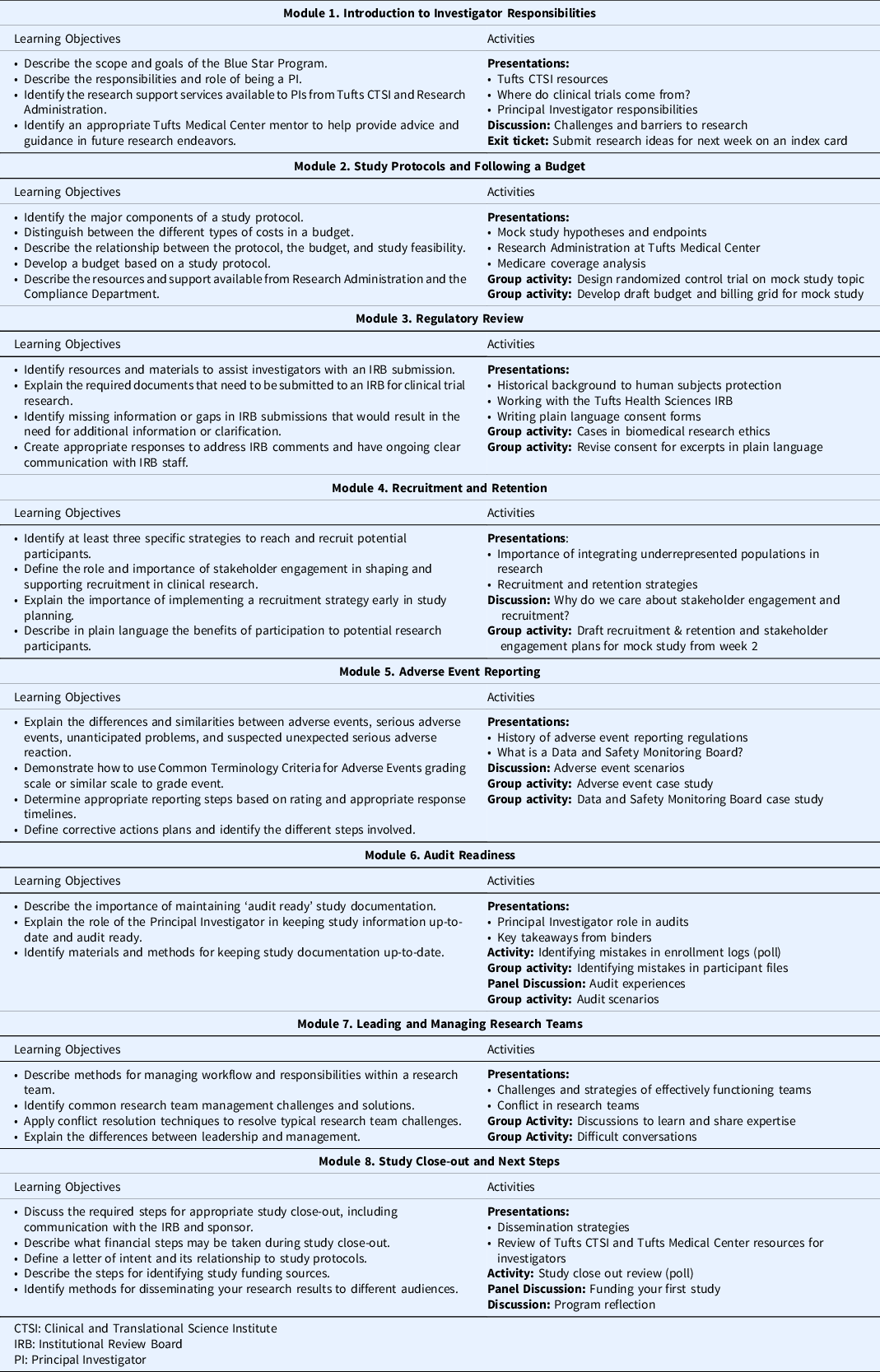

Prior to the start of the program, learners were required to complete the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative’s (CITI) Biomedical Research and Good Clinical Practice for Clinical Trials with Investigational Drugs and Medical Devices trainings. The Blue Star program consisted of eight modules delivered over eight weeks and was designed to guide participants through study conceptualization, design, conduct and monitoring, and close-out and results dissemination (see Table 1). Weekly prework material, estimated to take approximately one hour to complete, introduced module concepts and consisted of tutorials, short readings, regulatory guides, handouts, and related videos. All prework content was delivered asynchronously through the Tufts CTSI I LEARN learning management platform. Prework was timed such that each week’s content was released after the completion of the prior week’s live session. Weekly two-hour live sessions allowed learners to build on what they learned in the prework and previous modules, engage in group activities and discussion, and ask questions of content experts. For instance, in Module 2, learners developed an understanding of the components of study protocols and budgets and the ways in which these documents relate to study feasibility. Learners were given a research question and in groups, worked to define an intervention, study population, objectives, and a schedule of events. Then, learners used these elements to build their study budget. Content experts from the Research Administration and Compliance departments provided an overview of the budgeting process and the resources they offer to investigators. In Module 4, groups returned to their mock study to develop a plan for engaging community stakeholders and defining recruitment and retention strategies specific to their study population. Content experts from the CTSA institution provided feedback on learners’ plans and presented examples of successful recruitment strategies.

Table 1. Training program curriculum and activities

Program Evaluation

Program Participants

A call for applicants to the training program was released in Spring 2021 across internal hospital communication channels. Applicants were required to write about their previous experience conducting or contributing to clinical research, and their interest in future clinical research. The first cohort consisted of 11 clinician learners from across medical departments and specialties, including oncology, pediatrics, anesthesiology, rheumatology, surgery, endocrinology, and pathology. Most enrolled learners (N = 8) had an academic rank of Assistant Professor. A majority (N = 9) reported never previously serving as a PI on a clinical trial, but many had previous experience as a co-investigator, sub-investigator, or working as a research coordinator. We did not collect additional demographic information from the participants. The Blue Star program director contacted the supervisors for all accepted applicants to obtain written confirmation of three hours per week of protected time for program participation, a requirement implemented as a result of our experience in the pilot module. No tuition or fees were charged to participants or their departments for the program.

Evaluation Methods

Program evaluation is essential to assess the impact of our training program and to identify areas of improvement for future iterations of the program at our CTSA institution and for dissemination at partner sites. First, we wanted to determine if we had been successful at recruiting the targeted learners for this program, as evidenced by learners’ motivations for completing the Blue Star Program. Second, we sought to assess whether learners experienced a change in their confidence and preparedness in conducting clinical research following program participation. Third, we wanted to understand the impact of the program structure and format on learners and opportunities to improve the content for future cohorts. We conducted a mixed-methods evaluation including analysis of program evaluation data from January 2021 pilot participants and Fall 2021 participants, as well as a focus group with learners who participated in the Fall 2021 curriculum. This study was approved by the Tufts Health Sciences IRB. Of the 11 learners in the program, eight consented to participate in the IRB-approved research study.

Confidence and self-efficacy were assessed through pre- and posttest questionnaires delivered through the Tufts CTSI I LEARN platform. There were no pre- and posttest items developed for Module 1, as that module consisted of an introduction to the program and our CTSI resources. For each subsequent module, the pre- and posttest consisted of five items per module assessed on a self-efficacy scale from 1 (cannot do at all) to 8 (highly certain can do), for a total of 35 competencies measured during the program. Delivery of the questionnaires was timed such that learners answered the pretest questions for a given module before gaining access to the rest of the required prework content. Starting with week three, posttest questions for the previous module (e.g., module two) were appended to the pretest survey for that module, thereby allowing for the spacing out of the completion of the module and the delivery of the posttest questionnaire. One exception was the Module 8 posttest, which was delivered on a paper survey during the last 10 minutes of the final live session.

The 35 pre-and posttest items were drawn from three sources: the Joint Task Force for Clinical Trial Competency Core Competency Framework version 3.1 [Reference Calvin-Naylor, Jones and Wartak8,Reference Sonstein, Seltzer, Li, Silva, Jones and Daemen16] (N = 18), the Clinical Research Appraisal Inventory [Reference Mullikin, Bakken and Betz1] (N = 5), and original items written by the authors (N = 12) (see supplementary item for details). Competency items were finalized after the program content was completed to ensure that the evaluation matched the intended outcomes for each module. Overall confidence was assessed through one self-efficacy statement: “On a scale of 0 to 10, with 0 being ‘no confidence’ and 10 being ‘total confidence,’ how confident do you feel in leading your own clinical research study as of now?” delivered in a pre-requisite module before the start of the program and assessed again with the Module 8 posttest questionnaire.

In addition to the quantitative items, each posttest questionnaire included an open-ended question asking the learners to list their key takeaways from the prior module. Finally, the questionnaire for Module 8 included a series of 13 items designed to elicit participants’ subjective experience of the program format and delivery methods, assessed on a Likert-type scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree, as well as three open-ended (qualitative) questions covering program strengths, suggestions for improvement, and topics for future training.

To supplement the pre- and posttest surveys, we conducted a one-hour focus group in February 2022 (N = 3). The goal of the focus group was to probe more deeply into learners’ motivations for participating in the Blue Star program and to gain additional insights into the overall effectiveness of the program in preparing junior clinical investigators. The focus group conversation was transcribed. Two study team members (KM, SB) independently reviewed the transcript to identify key themes and quotations emerging from the conversation. Then, the two team members met to reconcile their initial findings. Despite the small number of participants, the themes expressed in the focus group conversation mirrored and gave added depth to the findings from pre- and posttest surveys, including the responses to the three open-ended questions in Module 8.

Target Learners

The demographics of the learners and statements made during the focus group session indicate that we were successful in enrolling clinicians who were interested in pursuing research, but who were not necessarily going to become full-time researchers. In our focus group, we asked participants what motivated them to apply to the Blue Star program. In general, participants discussed wanting to understand more about research terminology and research conduct. They were drawn to the program because they wanted to learn more about the PI role and what questions to ask. As one learner put it:

“I sort of suddenly was faced with this, “Wait, I have to be a PI now?” and what does that really entail? And do I know that I can handle that, just by the fact that I have all this on-the-ground information about what research and clinical trials should look like? So, it was very much, ‘Yes, I need more information for this new role.”

Learner Self-Efficacy Analysis

Given the small sample, we focused on descriptive statistics for this analysis. We calculated the medians and interquartile range (IQR) for each item and for the pre- and post-program differences in each item.

Results

Eight of the 11 participants opted-in to the research study. Median overall confidence in conducting clinical research before the start of the program was 3 (IQR: 1, 4.5); for the participants with complete pre and post-program data (N = 5), their confidence level increased by a median of five points (IQR: 4.0, 7.0) (Table 2). There were 35 items assessing the module-specific competencies. Due to space considerations, we selected one-to-two of the most important competencies for each module before analysis, for inclusion in Table 2. See the supplementary materials for a complete list of competencies assessed. For most competencies, the median and interquartile range of the change in participants’ perceived self-efficacy suggested improvement.

Table 2. Median Confidence in Selected Competencies (n = 8) a

a Scale range was 1 (Cannot do at all) to 8 (Highly certain can do).

^Median of within-participant change.

IQR: Interquartile range.

The qualitative feedback we received in the final evaluation survey and the focus group further illustrate that learners increased their knowledge of and confidence in their ability to run a clinical trial as a result of this program. As one focus group participant shared,

“…I felt like the program did a great job of that overview sort of start to finish. You know, it’s the kind of thing you also need to learn by doing, so I’ve certainly forgotten some of the things, but the program also provided resources, and it also will allow me to when I begin that journey in earnest ask questions and know what I need to ask questions about.”

Program Strengths

Learner responses to the final evaluation survey questions demonstrate that the format of the program was well received and perceived by the learners as very effective (see Fig. 1). Given the busy schedules of our participants, the eight-week duration and three-hour per week commitment could have been seen as burdensome. However, our participants felt very strongly that not only was this time well-spent, but that they in fact wanted more. For example, one participant suggested that we “lengthen the course to include actually writing and submitting IRBs and grants.” We also learned that the online prework was seen as valuable and relevant, and not unduly burdensome. Participants enjoyed having the mix of didactic online content and the active in-person sessions. One participant in our focus group summed it up this way:

“[O]ne other thing that I found myself appreciating throughout the course was just … the variety of different teaching modalities … the combination of someone standing up in front and kind of giving us the lecture but also the group discussions and … the prework. And even the prework had different … things to engage you and make you more interactive. I think that was good not only for kind of integrating and synthesizing what we’re learning, but also just to kind of keep us a little bit engaged.”

Fig. 1. Program format and delivery evaluation responses.

Participants called out the breadth and depth of the program, as well as the emphasis on the resources provided by our CTSA as especially valuable. As one focus group participant said:

“One thing I found very valuable was just, there are so many different groups of people here at Tufts employed to support research in many different ways, and I think I was just unaware going in that you know, research stat[istic]s support existed and someone to help me think through enrollment outreach existed, and someone to help me think through applications to the IRB … I think just the meeting and the networking and the understanding of who is here and who is employed by this system to help us was really, really valuable.”

Limitations and Next Steps

The Blue Star program was designed intentionally to recruit a small cohort, to support the hands-on, small group learning activities that were the core of our in-person sessions. The small size of the cohort prevents us from making generalizable claims about the program’s effectiveness. Due to COVID-19 and guest speaker availability, we had to hold three of our live sessions on Zoom instead of in-person. Feedback from all of the sessions was positive, but several learners pointed out in the open-ended evaluation questions that they benefited the most from the in-person sessions.

One of the clear takeaways from this first iteration is that we should increase the total number of sessions in the program. In particular, the qualitative feedback we received indicates that learners would benefit from having a specific project to work on and “protected time” within the program to write and refine that project. For the next cohort, we plan to move some additional didactic lessons to the online prework to make more time for new and expanded hands-on activities in the live sessions. We also plan to expand the program from eight to 10 weeks and add time within the program for participants to work on their own protocol. As we facilitated the modules, we also observed that participants were more engaged in in-person group discussions and activities compared with remote sessions. As a result, our plan for the next cohort is to hold 100% of the live sessions in person, pending the state of the pandemic.

The Blue Star program was designed to address two primary challenges: 1) to remedy the lack of research training in medical school in order to increase the pool of qualified clinical investigators and 2) to do so in a format that would be rigorous but meet the needs of busy clinicians. Our discussions with this first Blue Star cohort confirmed that for many clinicians who are interested in pursuing research, taking the time out from their careers to pursue an additional degree program is unrealistic. Overall, the results from our program evaluation show that we were successful in meeting both major goals with our first cohort.

Finally, the success of this program was also due in part to the interdisciplinary nature of our team. Much like clinical and translational science requires a team-based approach, the development of the Blue Star program benefitted from a team that combined expertise in all facets of clinical research, the physician perspective, and teaching and learning. The participants’ overwhelmingly positive experiences with the format of the program, in addition to the content, can be attributed to the thoughtful leveraging of techniques drawn from decades of research in learning sciences [Reference Norman and Lotrecchiano17].

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2022.446

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Andreas Klein, MD, for his leadership and vision as program director for the Blue Star Investigator Certificate Program. In addition, we received valuable data analysis support from Lori Lyn Price, MAS, and Janis Breeze, MPH.

This project was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR002544. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.