Theory

According to Second Language Acquisition (SLA) theory, developed by Stephen Krashen, the way humans acquire languages is through receiving input, usually aural, that is understandable; this is termed ‘Comprehensible Input’ (CI). Think, for example, of a parent talking to their child: when they ask the child, ‘Do you want milk?’, the milk is visible, tangible. The child understands that they are being offered milk. Parents don't just say this once, they offer it hundreds, even thousands of times. According to this hypothesis, the input (the parent talking) is comprehensible (the child understands it); the brain is trained to automatically make meaning.

In Latin teaching, some of the messages that students receive are comprehensible; the teacher uses pictures or gestures or translation to make the meaning clear. In any textbook, there will be sentences that students, through repeated exposure, actually acquire; if a student reads Caecilius in horto sedet enough times, it becomes comprehensible. The goal in a CI-based classroom is to increase the number of messages that are understandable, in order to give the brain a chance to acquire language. Even if a person is just getting started with deliberately providing CI, there are ways to make what one is already doing more comprehensible. When teaching with CI, there is also a shift in goals—from the short term (the vocabulary quiz) to the long term (the end of the year and beyond).

My Journey

When I first learned about CI, it was through the lens of a specific technique invented by Blaine Ray called TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling). The idea is that the teacher uses oral storytelling in the target language to provide CI; the technique involves lots of repetition and questioning. My modern language colleagues encouraged me to go to TPRS training; in that one-day workshop, the presenter, Carol Gaab, taught us vocabulary through a story in Hebrew, a language that almost no one in the room knew. By the end of the lesson, we had understood an entire story!

At that time I was using the textbook Ecce Romani. When I got back from my training, I decided I wanted to start using TPRS right away with my 5th graders – 10 to 11-year olds, their first year of Latin. I had two immediate goals: I wanted students to learn the vocabulary from chapter four, and I also wanted them to get extensive repeated exposure to the accusative case, which was the grammar topic of chapter four, in multiple declensions. I felt that the story, as it was written, did not have enough repetitions of accusatives, or of the target vocabulary words, so I wanted to have an additional vehicle for students to be exposed to both of those with simple, fun Latin. So, I wrote a story about a pig (porcus) who sees and hears a wasp (vespa), and is then stung by the wasp. Then I drew little stick figures to accompany my story. The next day, in class, I told the story out loud, using puppets, and asked students some questions in Latin to make sure they understood, with the secret goal of also having them hear the story one more time. After I had told the story, asked the questions, and made sure students understood, I finally put the storyboard, with just the pictures, in front of the students. Amazingly, the students were able to write the Latin I had told them reasonably accurately and using the accusative case! It was an epiphany for me; I had never mentioned the word accusative, taught them any rules about putting an m on the end of the word, never mentioned anything about declensions, and yet here they were, using Latin correctly. My own learning of Hebrew, plus my students’ immediate use of Latin, convinced me that this was right for me and for my students. I began, over the years, to try to increase the amount of Latin that was understandable for my students.

Baby Steps

Hearing about using Comprehensible Input is really exciting, and at the same time, most Latin teachers were taught, or teach, using grammar-translation; that is, students are taught the grammar rule, then they apply it by translating Latin into English. The shift in providing CI involves spending less time teaching about the language to spending more time using the language. One can implement some smaller chunks of time using CI, while still teaching grammar and translating. One must just be aware that when explaining grammar in English, students are not acquiring Latin. Grammar explanations serve a different goal - learning about Latin - that is valid, but it does not lead to language acquisition. Converting a grammar-translation classroom to a more CI-focused classroom is absolutely possible, and many teachers who go through the process of starting to provide purposeful CI start with smaller steps. Some who are just starting out with CI consider themselves to be ‘hybrid’ teachers; that is, they provide a lot of Comprehensible Input, but they also spend some time teaching about grammar in English.

Increasing Input (usually aurally)

The first step in providing CI might be to increase the number of messages in class that students hear. However, blathering on in Latin that students don't understand does not achieve the goal of comprehensibility; the messages must be understandable. On the other hand, one does not have to be a fluent Latin speaker in order to provide more messages in Latin. Simply reading passages aloud, or creating simple sentences using pictures are easy, concrete ways for students to hear more Latin. While the goal of most Latin programs isn't to produce fluent Latin speakers, the brain is most adept at making meaning from aural input. Increasing the time that students spend hearing Latin is helpful to this goal. There are several simple and specific techniques that CI teachers use to increase the amount of Latin that students hear.

1. Describe a picture (‘Picture Talk’ inventor Chris Stolz)

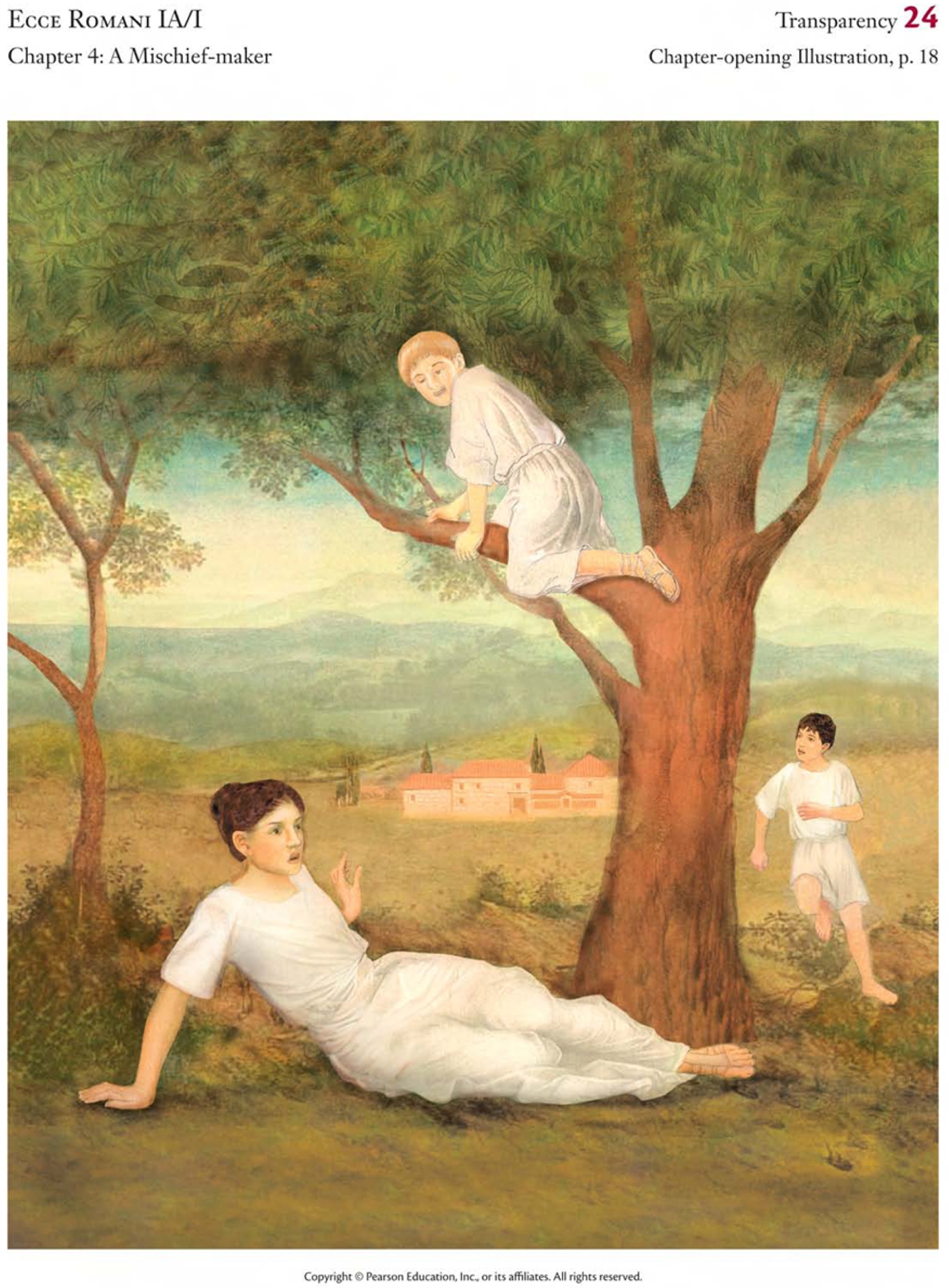

‘Picture talk’ is the process of projecting any image and describing it, slowly, in Latin, while also pointing at the pictures and the target words. If you're using a textbook that has interesting and useful images, use the target vocabulary words to describe one of the pictures in the textbook. To have more student involvement, also ask students questions about the pictures; remember the goal isn't so much that students produce Latin, but they hear a lot of Latin. Here is how it works.

a) Find a picture that has a nice combination of people or things and actions. Your textbook may have good pictures but try looking outside the book for interesting pictures that use the target vocabulary.

b) If you haven't yet showed students the word itself, write or project the word on the board or the picture itself, and, if it's not obvious, a translation. Comprehensibility is everything: make sure students know what the words mean. It may seem obvious to you, but it is not obvious to them. Even words that seem like obvious cognates are not obvious to them.

c) Project the picture and make statements very slowly in Latin while pointing and pausing, both at the words and images. Then ask questions about the picture and about the things you've said about the picture. Students answer as a class, or individually. You restate what students say in the correct language.

This picture is taken from the textbook Ecce Romani. I know I want to target certain vocabulary words (arbor, ascendit). This gives the basic plot of the story, while also holding back something … the fact that the boy in the tree falls out. This is important to build suspense and interest.

You will notice in that entire sequence the teacher repeats the word arbor at least six times, possibly more, taking student answers into consideration. Furthermore, students have just heard arbor used in nominative, accusative, and ablative cases, giving students’ brains a chance to make long-term meaning of case uses.

An additional picture-talk technique is to put up a wild, crazy, unusual or controversial picture, but one that uses the same vocabulary; student interest is inherently higher and you can use the same vocabulary words to describe the picture. You could also use the second picture to compare the two pictures.

Describing a picture works well for any level of Latin; the example I have provided just happens to be Latin 1, but you could certainly take a picture of a painting of the Metamorphoses and describe it using words in Ovid; you could also use a picture of someone about to fall off a cliff and describe it using result clauses. The possibilities are endless.

2. Movie Talk/Clip Chat (inventor, Ashley Hastings)

A natural extension to picture talk is to play a short clip from a film that features the vocabulary you are interested in using. Ideally the film is silent or has no talking and is short; less than five minutes. At certain points in the film, you pause it and describe what is happening, but in Latin. A key component is to pause right before the end for students to make predictions (in English or Latin, depending on your comfort level); try not to reveal the end in the actual movie talk. This helps build suspense and student interest. When you have finished describing the film with lots of pausing, play it one time through for students to enjoy the whole film.

3. Circling/Questioning (inventor Susan Gross)

Take any text that you are working on and ask students scripted questions about the plot of the text. This is different than asking questions to find out what students know; although you might find out what they do or don't understand during the course of this exercise, the point is actually for students to hear the target structures multiple times.

The questioning process is similar to the questions you ask about the pictures; students are hearing Latin in different formats. The usual formula is to ask a question where the answer is ‘yes’; one whose answer is ‘no’; an either/or question, and finally an open-ended question. Posting question words, as well as response words (ita, minime, nescio, etc.), somewhere prominently in the room is particularly helpful for this type of questioning. In a reading passage, one could ask the following;

From Stage 13 of Cambridge Latin Course: tres servi

Target vocabulary/structures: posse / velle + infinitive

If my target structure is coquere vult, in that questioning sequence, students heard it a minimum ten times. Note: you will want to VARY the order of the questions, or students will quickly catch on that you ask the questions the same way each time. The questioning sequence may seem a little stilted at first, but, used sparingly, it is a good way to provide students with input.

4. Storytelling (inventor Blaine Ray)

The technique I find myself coming back to again and again is storytelling; the official technique is called TPRS (Teaching Proficiency through Reading and Storytelling). Students find it incredibly compelling, and compelling input is more comprehensible; students are naturally more tuned in to things they find interesting. It gives students a voice and a choice. It is also, arguably, the hardest. Storytelling involves using the vocabulary and turning it into a narrative arc. To increase comprehensibility, either draw (or have a student draw), or have students act out the stories that are created. Then type up the story and you have a reading.

First, take your vocabulary list, and see if there is a place where you could make three or four of the words into a story, something unusual or interesting. For example, as I look at vocabulary for a particular story, I know I want to use the words canis, vult, habet and laetus or tristis. The characters in the story really don't matter; what is important is that students hear structures they will later read. I write out a script that will give students some choice, but mostly leave the story in my control. I want to make sure I have a setting and characters, a conflict, and a resolution.

Characters and Setting

X Student has a dog named Z. X Student lives in place.

Conflict

Y Student wants a dog. Y wants a dog named Z.

Y takes the dog named Z.

X is happy because dog named Z is bad/annoying.

OR

X is sad because her dog is good and X wants her dog back.

Resolution

X grabs her dog / Y returns dog / Y keeps dog (whatever makes sense)

After creating this story, I can use it again in several extension activities. We can draw the story, while narrating in Latin; we can act it out, in Latin. We can write up the story and read it. We can write an alternative version and read that. Students absolutely love creating class stories - we call them fabulae ridiculae - and they create such a strong sense of classroom culture. After four years of Latin, students still reference the stories they made up in fifth grade.

5. Sustained Silent Reading

Not all input needs to be aural, especially in our Latin classes where we are training students to read. A non-aural way to increase the input students get is to have them read more understandable Latin! It is important that they read Latin that they already understand or you know to be at or below their level; their enjoyment of the text and ability to understand quickly is paramount. This is NOT about translating, this is about reading to gain input.

Students can read copies of the class stories that you create; they can reread old stories from the textbook; or they can read other materials that you make available to them. Older readers pitched as ‘easy’ are usually not easy enough, but in the past few years, quite a few Latin novellas have been written for novice Latin learners, and these books form the basis for classroom libraries. Most of these can be ordered from Amazon. There have been ‘minibooks’ written to accompany the Minimus series, which are easily available in the UK.

Students choose their own books, get comfortable, the teacher sets a timer, and students read for five to ten minutes, several times a week. It is nice when the teacher reads along with them, to model the importance of this time. For the most part, the reading itself is the activity, and there is no further action taken on the books: no tests, no reports, no worksheets. Only if you need to implement accountability for behaviour issues would any kind of log or assessment be necessary.

Increasing Understandability

In addition to providing more input, the second step would be to start to think about ways to make stories or sentences more understandable, but not by turning them into English. A presentation by Marcos Benevides at the 2015 IATEFL conference, titled ‘Extensive Reading: Benefits and Implementation’ shows that once a reading falls below 90% of known words, it becomes almost incomprehensible. Our students have been translating Latin at far below 90% of known words; we give them glosses to help them deal with it, but they aren't actually READING Latin. Instead they are slowly decoding, and then translating into English in order to understand it. There are several ways to make readings more understandable.

1. Pictures

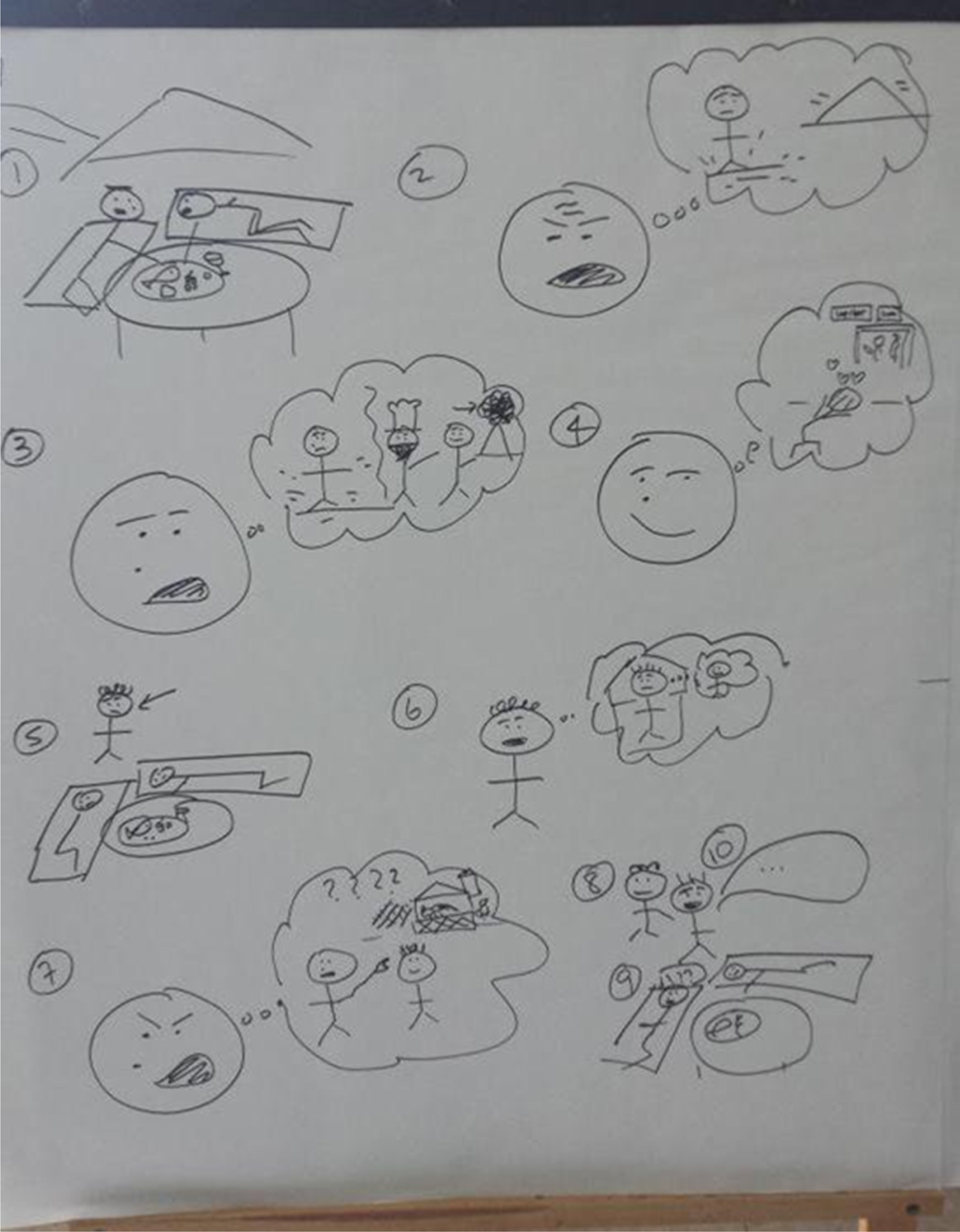

If your textbook does not have pictures that make the text more understandable, you draw pictures or make a PowerPoint to accompany the text, so the meaning is more understandable. Once the picture is made, you will have it forever. Taking the text sentence by sentence with a picture to match (picture-book style) may help students understand the stories without having to turn them into English. Students could also demonstrate their understanding of a story through drawing; student drawing is not INPUT, but it is also moving away from only translating as a way to show they understand a text. Below is series of drawings I made to accompany the story tremores from CLC stage 12. I told/read the story aloud to students while I pointed to these drawings; then students were given the text and asked to read it. Their comprehension was much higher because they had detailed drawings to help them make sense of the story.

2. Tiered readings (inventors Laurie Clarq and Michelle Whaley)

Some teachers have begun extensive work on actually adapting readings to make them more understandable. The idea is that students work their way through materials of varying difficulty until they get to the final (unadapted) version. The first iteration is a simplified version of the text; maybe the word order is in English order or, if a poem, in prose order, and synonyms are given for unknown words. The second iteration adds some of the unknown words back in, and includes more details. The final version is the original Latin, unadapted.

Take for example, the following tiered readings of De Bello Gallico, made by Kevin Ballestrini of the Pericles Group (http://lapis.practomime.com/index.php/quick-links/operation-caesar-reading-list).

One possible critique is that students are using the first tier as a crutch to get them through the third tier; but if we give them the third tier, they are using dictionaries, grammars, and translations to get them through it. In the embedded way, the students are staying entirely in Latin, even if that Latin is simplified. They are more closely reading, receiving input, than if they switch into English.

New Approaches to Vocabulary

One of the gurus in the CI world, Susan Gross, has said ‘Shelter vocabulary, not grammar’. That is, the sheer number of vocabulary words in textbooks is overwhelming; handing students a list of 20-25 words and expecting all of those words to be acquired is just not going to happen. Can students put 20 words in their short-term memories and spit them back out for a quiz? Of course. But that is not long-term acquisition. Teaching for long-term acquisition means scaling back the number of words that students are expected to know.

Stick-figure illustration of CLC Stage12 tremores. Photo by Michelle Ramahlo.

Instead, see if you can focus on a few vocabulary words at a time, rather than the entire list. When you approach your textbook chapter, think about what words are essential for students to be able to read a story. Keep the words that seem absolutely crucial for understanding. Furthermore, if there are words that are not very common in the Latin readings you know they will encounter later, those can also be crossed off the list too. One resource is the Dickinson College Commentaries (http://dcc.dickinson.edu/latin-vocabulary-list), which maintains a list of word frequency. Any word on your vocabulary list can be cross-referenced with how common it is in all of Latin literature. (The highest frequency word: et.)

In addition to limiting the words, you can change how students learn the words. Instead of handing children a list of words, try doing things with the words. Have students act out or create gestures for the words. Use the words in picture talk or movie talk. If it's a noun, ask students if they like it; if it's a verb, ask students if they do it. Turn the action words into imperatives and move students around the room: command them to ambula ad ianuam or curre ad amicum. Play Simon Says with the same commands. Have students draw pictures of the words. The more ways you can use the words, the better understanding students will have when they encounter them in their readings, and the better they will retain the words.

Moving Forward with CI

Many CI-based teachers, after they become comfortable, begin to think of ways to move away from textbooks entirely, precisely because they have too much vocabulary, the stories and syllabus are driven by grammar, and because the Latin itself is very much unlike what students will encounter when they begin reading Latin. This move is easier if one is very comfortable speaking Latin; it also may be out of the Latin teacher's control. They naturally want to provide more and more input, and so they may use other techniques such as story asking, implementing brain breaks, discussing grammar in the target language, task-based units, writing year-long stories, and more.

Regardless of textbook use, CI-Latin teachers are always finding new ways to provide ever more input that is comprehensible, compelling and caring. CI-classrooms are flexible, fun environments where students have a voice and a choice, even if the teacher is doing quite a bit of speaking.

Training and Resources

Over the summer, and throughout the year, there are training sessions dedicated to bringing these techniques to teachers. The largest CI-specific training sessions are the National TPRS Conference (NTPRS), July 8-12 in Chicago, Illinois, and the International Forum on Language Teaching (IFLT) July 15-18 in St Petersburg, Florida. The Institute of the American Classical League will have sessions on CI in the Latin classroom this summer June 25-28 in New York City.

Much of the work of implementing CI in the classroom is done by individual, isolated teachers, but a network of Latin teachers has developed online to support each other. There are Facebook groups devoted just to the exchange of advice and information. In particular there are several blogs with tons of resources, advice, information, and activities, many of them written by authors in this very journal. These experienced and creative teachers describe their techniques, discuss the setup of their classrooms, share materials they have made, and provide ancillary materials that accompany the novellas they have written.