Introduction

This investigation was inspired by the unprecedented and utterly unpredictable circumstances teachers and students alike were thrust into by the COVID-19 pandemic. With so much yet to learn about the pandemic's effect on student learning in and beyond the classroom, I took the opportunity of the remote learning period to conduct a research project focusing on how teachers can best adapt their lessons to accommodate online learning while also remaining conscious of the needs and interests of their students. The effects of this event have certainly been felt within the Classics classroom, with Hunt noting that ‘for the study of classical languages and literature, there has been little for teachers to turn to that is relevant to their immediate needs during this crisis’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2020, p. 33.). In particular, I wanted to explore whether the digital platforms available to teachers were suited to meet the demands of online learning, and whether students themselves felt that they had made good progress in their learning as a result of using these platforms.

The use of technology in the classroom is nothing new. For the last 30 years educators and academics have pondered how technology might be employed in and beyond the classroom in order to create and take further advantage of all learning opportunities. Fundamentally, as Gibson notes, this is a crucial step in renovating pedagogical practice in an era where the ways in which people ‘access, work with, and communicate information’ changes by the decade (Gibson, Reference Gibson2001,40). Unlike previous investigations, however, this paper contributes to an emerging field of study on the remote learning period and, as such, it is necessary to once again evaluate how we might make use of technology in our lessons when circumstances demand it. As this paper demonstrates, digital learning platforms hold the potential to not only assist educators in coping with the challenges of remote learning but also to further student learning in ways once considered unimaginable beyond the realms of the physical classroom.

In my case study investigation, I planned to make use of the digital learning platform PadletFootnote 1 in my lessons conducted over the remote learning period, due to a number of unique features it offers which enable students to remain anonymous (at least to other students) in their answers and provide a springboard from which to deliver impactful student-led discussions. I chose to conduct this research project with my Year 8 class, as they have spent more time in school under ‘pandemic’ arrangements including remote learning than the ‘normal’ conditions of daily school life, which I believed made them suitable given the nature of the questions being posed in this paper.

Research Context

I conducted my research during my second professional placement at a state-maintained girls’ grammar school. The students at this school were required to pass the 11+ exam in order to be admitted, and the school itself is ranked in the top 14% of schools nationally in its Progress 8 score measuring student performance in GCSE examinationsFootnote 2. The school is the only state-maintained school to offer Latin in the area, competing for students only with a nearby fee-paying private school. Latin is mandatory in Years 7 and 8 (students aged 11-13), after which students are able to either continue their Latin learning or select another from a variety of modern foreign languages. The Classics department is greatly admired by the staff and students alike, boasting a high student retention.

The class I worked on this project with is made up of 30 students, and consists of a variety of personalities. This was the premise behind my decision to conduct my research with this class in particular, as I felt I would be able to gather the greatest variety of data and evidence on the questions being explored given the variability of classroom behaviours and levels of participation. The class achieves a high academic standard overall, with 21 students scoring over 80% in their most recent summative assessment. Ultimately, the classroom composition of this Year 8 class in particular worked in my favour in various ways, facilitating the collection and detailed analysis of data.

Literature Review

The remote learning period is an emerging field of study which will certainly be the subject of many studies and investigations in the future. Given how recent the online learning period is, however, substantial work analysing it is difficult to find. Our understanding of the remote learning period's impact upon learners’ education is a hot topic within both academic and political spheres, with calls for a shortened summer break (Gill, Reference Gill2021) and summer ‘catch-up’ programmes springing from a fear that online learning has brought learners’ education to a grinding halt (McMullen, Reference McMullen2021). My literature review will therefore firstly consider the current data on remote learning, and how this has informed my approach to this research project. I will then analyse previous studies on the potential digital education has to innovate classroom pedagogical practice, and conclude with an evaluation of the blended learning theory and its relationship with online learning during the pandemic.

Remote Learning

On the 24th April 2020, a month following the first closure of schools in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the Education Endowment Foundation published a rapid evidence assessment which examined 60 systematic reviews and meta-analyses for possible approaches schools could adopt to offer effective remote learning provisions for its students (EEF, 2020). Its findings have been summarised below:

1) Teaching quality outweighs lesson delivery in remote teaching.

2) Accessibility is remote learning's greatest challenge - technology is key.

3) Peer interactions can motivate students and improve lesson outcomes.

4) Giving students the opportunity to study independently can be greatly beneficial.

5) Different teaching strategies and online provisions must be made to cater to all pupils.

It appears, then, that early research into remote learning and how it ought to operate suggested that teachers should replicate the classroom environment as far as possible in terms of student engagement, but should take advantage of the opportunity for students to complete independent work. A very interesting statement by the EEF in this report is that ‘many forms of digital technology could in theory be used to support remote learning, but are typically used in schools and have not been evaluated as remote learning tools’ (EEF, 2020). I find this particularly intriguing as it is an acknowledgement that digital technology has the potential to facilitate remote learning, but this possibility could not be explored further as there was a distinct lack of research on the topic. This proves the relevance of this research paper in its key objective of assessing how teachers can make use of digital platforms in providing sufficient remote teaching provisions, and proves its contribution to the field.

If the EEF's suggestions on the ‘ideal’ remote learning provisions were published so soon after the emergence of the pandemic and closure of schools, why does there remain so much doubt and uncertainty over young people's remote education today? On the 8th April 2021 Oxford University published a survey of studies conducted in the Netherlands over the last year, which the surveyors believe is applicable to the UK in its findings (Oxford University, 2021). Dr Per Engzell, chief conductor of the study, states that ‘students made little to no progress while learning from home and losses are particularly concentrated among students from homes with low levels of education’ (Engzell, Reference Engzell2021, 1). This is a concerning finding, as it suggests that the ‘educational gap’ between children of highly-educated and lower-educated households could increase as a result of online learning, with a consequential increase in class division and educational disparities. Mark Verhagen, a doctoral student at the University of Oxford who analysed the significance of Engzell's study for the UK, states that ‘teachers’ actions and school policies seem to play an important role in mitigating the negative consequences of the pandemic’ (Oxford University, 2021), and this inspired my approach to this research project. As teachers are ultimately responsible for online learning provisions, I felt it necessary to give students a sense of autonomy over the Padlet platform and to minimise my influence in order to test Verhagen's hypothesis.

Ultimately, the research into the impact of online learning on young people's education is ongoing. Therefore, it would be presumptuous to suggest any definite conclusions on the topic, and I have chosen not to do so in this paper. What I can certainly conclude from my review of existing literature on remote learning however, alongside Engzell, is that ‘only time will tell whether students rebound, remain stable, or fall further behind’ as we emerge from the era of online learning (Engzell, Reference Engzell2021, 5).

Technology in the Classics Classroom

According to Hew, the perception of technology as an instrumental tool originates in the work of Aristotle in his suggestion that ‘technological products have no meaning in and of themselves and that technology receives its justification from serving human life’ (Hew, 2018,3). Naturally, the ‘technology’ Aristotle is discussing and the technology in question within this paper are two entirely different entities, but from this one significant question arises: can technology be used in the classroom as an instrumental tool, and if so, how beneficial would it be? With this in mind, I will now discuss the existing literature on using technology in the Classics classroom.

This topic has been discussed in numerous articles and books due to the prospect it offers of renovating the traditionally didactic study of the ancient languages for a generation born in the digital age. Walden, for example, explores the rise of distance learning courses as a result of specialised teacher shortages and the increased popularity of mature learning courses (Walden, Reference Walden, Natoli and Hunt2019), complementing studies analysing the facilities offered for independent learning by platforms such as Quizlet and Memrise (see, for example, Walker, Reference Walker2016). Atkinson (Reference Atkinson2012) has also conducted a study of this kind, which has influenced the way in which I utilised Padlet in my research lessons. Atkinson discusses her own experiment with using technology in the classroom, with the overarching purpose of ‘encouraging a few more Classics departments to investigate the possibilities of using [technology] as a tool for independent and collaborative learning in the future’, thus ‘putting Classics… at the forefront of educational innovation’ (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2012, 25). In this article, Atkinson describes how Pinterest, the platform she experimented with, hid user information on the class page she designed, as ‘the focus is deliberately on what is posted, not the user’ (Atkinson, Reference Atkinson2012, 24). This reminded me of the features available on the Padlet platform, particularly the anonymous feature, and inspired me to make anonymity and its impact on student engagement a central focus of my research project. Despite Atkinson's research being completed prior to the Covid-19 pandemic it sets a precedent for future research into the integration of digital tools within the classroom in an attempt to complement the natural skills of the 2000s generation.

Despite this, not everyone is as keen as Atkinson to integrate Classics with the digital platforms available to teachers. Chadwick, for example, notes that ‘it is simply not enough to imagine the use of technology in the teaching of Classics is a panacea for all of our problems’ (Chadwick, Reference Chadwick2013,8). However, it is important to note the distinct difference between the time in which Chadwick wrote this article and the circumstances teachers find themselves in today. Firstly, the integration of technology into everyday teaching became a necessity for learning during the remote learning period, as without successful use of platforms such as Google Classroom, Microsoft Teams or Zoom, ‘live’ teaching of lessons would simply be inoperable. Moreover, the technologies available to teachers have changed dramatically over the past eight years since Chadwick's article was published, with the emergence of platforms such as Padlet changing the way in which teachers think of technology in the classroom. The remote learning period presented an unprecedented challenge for students and teachers alike, and I believed this project was a prime opportunity to assess to what extent Chadwick's words warned of the challenges of this past year and if they still ring true today.

I should also note the technologies teachers have relied on in the teaching of Classics, as this will form the basis of comparison when analysing the effectiveness of Padlet in furthering student learning over the remote learning period. The Cambridge Latin Course (CLC) is the most widely used Latin textbook in the United Kingdom, with over 90% of schools which teach Latin using it in the classroom (CSCP, 2021). In response to the pandemic, the Cambridge School Classics Project put together a number of free online resources for the CLC to help teachers deliver successful remote lessons in Latin. Upon closer analysis, we can see that the digital resources the CLC prepares are geared toward assisting the teacher, and less focus is given to providing resources for students themselves to complete work independently. This encouraged me to consider in this project to what extent technology can be used to supplement and support students’ independent work over the remote learning period, as this is an avenue of technology implementation which has not been sufficiently researched.

Factors Affecting Student Participation Levels

The next section of my review will assess existing literature regarding the factors which may impact or influence the way in which a student chooses to engage with lessons through discussions, such as social anxiety.

Abi-Najem defines social anxiety as ‘an excessive or unreasonable fear in social situations. For students, the symptoms frequently manifest in the classroom’ (Abi-Najem, Reference Abi-Najem2015). Some of these symptoms include ‘anxiousness and speaking up out of fear of looking bad’ (Abi-Najem, Reference Abi-Najem2015). According to the National Institute of Mental Health, approximately 9% of students suffered from Social Anxiety Disorder between 2001-2004 (NIMH, 2021). This can be compared to 17.2% of under-16s rating their anxiety levels as ‘very high’ between 2011-2012 according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS, 2020). This indicates a significant rise in anxiety levels between these two periods, or at the very least a wider self-recognition of anxiety-related behaviours among young people, which Casbarro (Reference Casbarro2020) states is partly due to the rise of social media and its usage by young people. This research project therefore tests the correlation between digital platforms and social anxiety in the classroom, and how we can use these tools to create a more effective and supportive educational climate. For example, I believed implementing the anonymous feature in students’ Padlet submissions would help alleviate worries relating to ‘looking bad’, and I wished to examine by means of a further focus group interview students’ thoughts and interactions with this feature.

It is important to note, however, that social anxiety is not the only factor affecting a student's likelihood to participate in wider class discussions. According to Casbarro (Reference Casbarro2020) other factors include (but are not limited to): academic pressure, competition and comparison, bullying, natural disposition, and what he describes as ‘pandemic-induced stress’ where ‘home is no longer the respite from what may be a stressful school life’ (Casbarro, Reference Casbarro2020,2). This in itself makes attempting to ‘measure’ student participation incredibly difficult given the sheer number of factors to be taken into consideration in order to do so effectively, and this certainly lies beyond the scope of this paper. What this has inspired me to do, however, is to turn once again to the students, as it is much more feasible to examine how they themselves articulate their experiences of using Padlet and how this platform affected the ways in which they participated in class discussions over the online learning period.

The Blended Learning Theory

I will conclude my literature review by investigating the ‘blended learning approach’, a novel pedagogical technique which I believe shares many similarities with the teaching required during the remote learning period. Hew defines blended learning as the ‘integration of online and face-to-face strategies’ in the classroom (Hew, Reference Hew2014, 2). The initial impetus behind blended learning was its ability to accommodate the busy lives of (particularly adult) learners while also sufficiently meeting their educational needs, such as ensuring those with work or family-related responsibilities still had access to education (Hew, Reference Hew2014). It is fascinating to observe the similarities between the blended learning approach and remote learning, such as the emphasis on marrying online platforms and typical classroom teaching techniques such as student-led discussions.

Hoyos et al.'s 2018 action research study with High School students in the U.S. paints a clear picture as to why the blended learning approach struggled to gain a foothold in the typical classroom prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. This study bears some similarities to my research project, as the researchers introduced a Mathematics-based digital platform into their teaching in order to assess to what extent it helped to prepare students for university-level academic content (Hoyos et al. 2018, 51). The research team concluded upon the completion of the project that the blended learning theory they adopted improved the quality of teaching being delivered and the amount of information students were able to retain, recommending that students ‘learn better from a lecture supplemented with computed-assisted instruction, rather than from a lecture alone’ (Hoyos et al., Reference Hoyos and Silverman2018, 64). Although there are important distinctions to be made between a lecture-style learning programme and the typical teacher-led lesson my Year 8 students would be familiar with, I believe this study is beneficial to my research in that it functions as an essential piece of data precluding the rise of remote learning in 2020 and 2021. It certainly appears that evidence in favour of the blended learning approach via academic research and evidence-based studies was building momentum before being thrust into the pedagogical spotlight when online learning became the norm across the world.

In conclusion, my survey of existing literature on the topics being explored in this paper has revealed a gap in existing research. I could not find any research on the use of digital learning platforms during the remote learning period, or any substantial evidence confirming how the remote learning period has impacted student learning. I believe this is partly due to how fresh the topics at hand are as a field of study, and although I must acknowledge the work produced on collaborative approaches to digital learning, such as Walker's exploration of Memrise as a vocabulary-learning tool (2016) or Natoli and Hunt's edited volume Teaching Classics with Technology (Reference Natoli and Hunt2019), I am certain that many more interesting findings will be made in time when more research can be conducted. This literature review has proved the relevance of this project, and with the topics raised in this review in mind I will now turn my attention to the project itself.

Research Questions

There were three main research questions which I took into consideration when planning and sequencing my research lessons:

RQ 1: Does the use of Padlet improve and provide further learning opportunities for students in the remote learning period?

RQ 2: Does the opportunity to answer anonymously influence the ways in which students respond to questions set on Padlet?

RQ 3: How do the students themselves articulate their experiences of using Padlet over the remote learning period?

The digital platform Padlet also presented a unique opportunity to interrogate and assess the influences behind a student's behaviour and contribution to the classroom, particularly whether a student is more likely to participate in wider discussions if they were aware that their answers would be anonymous to their peers. Given the varied composition of students in the class, I was curious to investigate if the opportunity to contribute anonymously would encourage the more soft-spoken students to offer suggestions or ideas to the debates being discussed, and if so what this could suggest about how we might make successful use of digital platforms in the classroom following the conclusion of remote learning.

Teaching Sequence

My research lessons involved four different Padlet activities focused on the stories and content of CLC's Stage 11 Candidati¸ which were subsequently implemented and explored within four ‘live’ lessons over the remote learning period. These lessons began the week prior to February half-term, and concluded in the second week in March when government guidance allowed students to return to school. I chose this time period to conduct my research as we were about to complete the previous Stage in Book 1, and thus the introduction of Stage 11 provided a suitable opportunity to begin using Padlet in our lessons.

The government decision to allow students to return to school on March 8th affected my intended teaching sequence. Teachers were given two weeks’ notice of this return, meaning I had less time than expected to deliver my research lessons. Had circumstances permitted it, I would have liked to have delivered and discussed more Padlet assignments with my class in order to enrich the quality of my collected data and provide students more to reflect on when describing their experiences with using Padlet.

Ethics

All students were made aware of this research project prior to the commencement of my research lessons, and these lessons were approved by my mentor before being delivered. I engaged in frequent discussion with my mentor as to how best to complete the study in line with the British Educational Research Association's guidelines (BERA, 2018) and the school's various data-protection policies.

In this project, all students mentioned have been anonymised.

Methodology

Gerring states that a successful case study investigation makes use of both quantitative and qualitative data, lending itself to ‘characteristic flexibility’ in the results it produces (Gerring, Reference Gerring2006, 33). The survey completed by students involves a mix of quantitative and qualitative data, adhering to this statement.

As Gerring also notes, ‘case study research, by definition, is focused on a single, relatively bounded unit’ (Gerring Reference Gerring2006, 33). As my research lessons focus on the ‘single, relatively bounded unit’ of Stage 11 in the CLC, the parameters of my research are fixed and unmoving. In terms of the potential this project holds to shed light on students’ wider experiences with remote learning, this paper functions as a specific and individualised study designed to assist educators in navigating the complex learning environment we find ourselves in as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, where the boundaries between digital and ‘live’ learning have been blurred. This conforms to the purposes behind conducting case study research as defined by Gerring (Reference Gerring2006).

My reading and exploration of various methodological techniques impacted the way in which I collected data from my class. Merriam and Tisdell state that qualitative researchers are interested in ‘understanding how people interpret their experiences, how they construct their worlds, and what meaning they attribute to their experiences’ (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015, 6). Ultimately, qualitative research is conducted in order to understand the experiences of its subjects. As a key research focus of this project is to amplify the student voice in the discussion regarding the remote learning period, I made sure to frame my questioning so as to provide my students with the opportunity to express their opinions on the remote learning period and the platforms used within this time.

There are certainly some unavoidable limitations to this project which are worthy of consideration. For example, a minority of students did not contribute to the Padlet page, largely due to technological or accessibility issues, meaning that my findings are not entirely complete. I attempted to remedy this issue by asking these students to reflect on our use of Padlet in lessons rather than their own contributions, however this is not a perfect solution. As the remote learning period began in early January, I was not able to teach the class in person before the research was conducted meaning that no pre-testing or observation of the class in their ‘normal’ working environment could be completed. While I believe my findings are potentially indicative of a general consensus among students in my school regarding the remote learning period, the subjective nature of my questioning and the variance in remote learning provisions in each school make it unlikely that my research can be used in isolation to draw conclusions on a holistic, national basis.

Research Methods.

As previously mentioned, my project makes significant use of qualitative data, in addition to a small sample of quantitative data to supplement and reinforce my findings. The methodology of my research largely follows the ‘embedded case’ design, which makes use of both qualitative and quantitative data in order to reach a more reasoned conclusion (Scholz et al., 2002, 21).

My data collection was conducted in three distinct stages throughout the research period. First, I made observations on student engagement with Padlet when assigning and reflecting on the class's submissions. Then I conducted a whole-class survey asking them to reflect on the positive and negative aspects of using Padlet over the online learning period. Then, I chose a select number of students to interview further on the basis of their answers, selecting those whose answers had the most potential to benefit from further discussion. I felt strongly that my decisions on who to select for further interview should not be based on academic ability or prior participation in the classroom, as by focusing on the students’ own words I am keeping with the desire to put the student voice at the forefront of my research as stated at the beginning of this paper.

Self-Completion Questionnaire

Schutt et al. (Reference Schutt and Check2011) states that ‘although a survey is not the ideal method for learning about every educational process, a well-designed survey can enhance our understanding of just about any educational issue’ (Schutt et al., 2011, 160). I decided that the most efficient and ethical means of gathering class consensus on their experiences of using Padlet and the remote learning period itself would be to conduct a survey. I ensured that my questions were worded with care so as to avoid confusing those who chose to participate, and to avoid ‘encouraging a less-than-honest response or triggering biases’ (Schutt et al., 2022, 160). These questions were paired with two Likert scale questions to provide quantitative data to supplement the qualitative data gathered from the other areas of the survey and interview.

Focus Group Interview

Prior to the interview, I had planned which questions to ask the focus group based on their answers in the Padlet self-completion survey. This was to ensure that the interview itself had an element of structure to it that meant we could discuss the most prominent points of contention I was able to glean from the survey. These questions fell into three distinct topics: the anonymous posting feature of Padlet, the means in which feedback was delivered, and the students’ experiences of online learning in combination with the Padlet platform. The conducting of this interview was therefore deliberately informal.

Data and Findings.

I believe the most clear and effective means of relaying my findings is via the order in which the research was conducted, beginning with observations made by myself and my mentor during the research lessons and concluding with the focus-group interview. In this way, following acute investigation and evaluation, my conclusions will become increasingly detailed in correspondence with the increasingly detailed nature of the data.

Class Observations

Both my mentor and I were keen to ensure that all observations made during the research lessons were framed to focus on how students engaged with the Padlet questions and content. Student experiences of navigating the platform itself were supplemented in the self-completion questionnaire and subsequent focus-group interview.

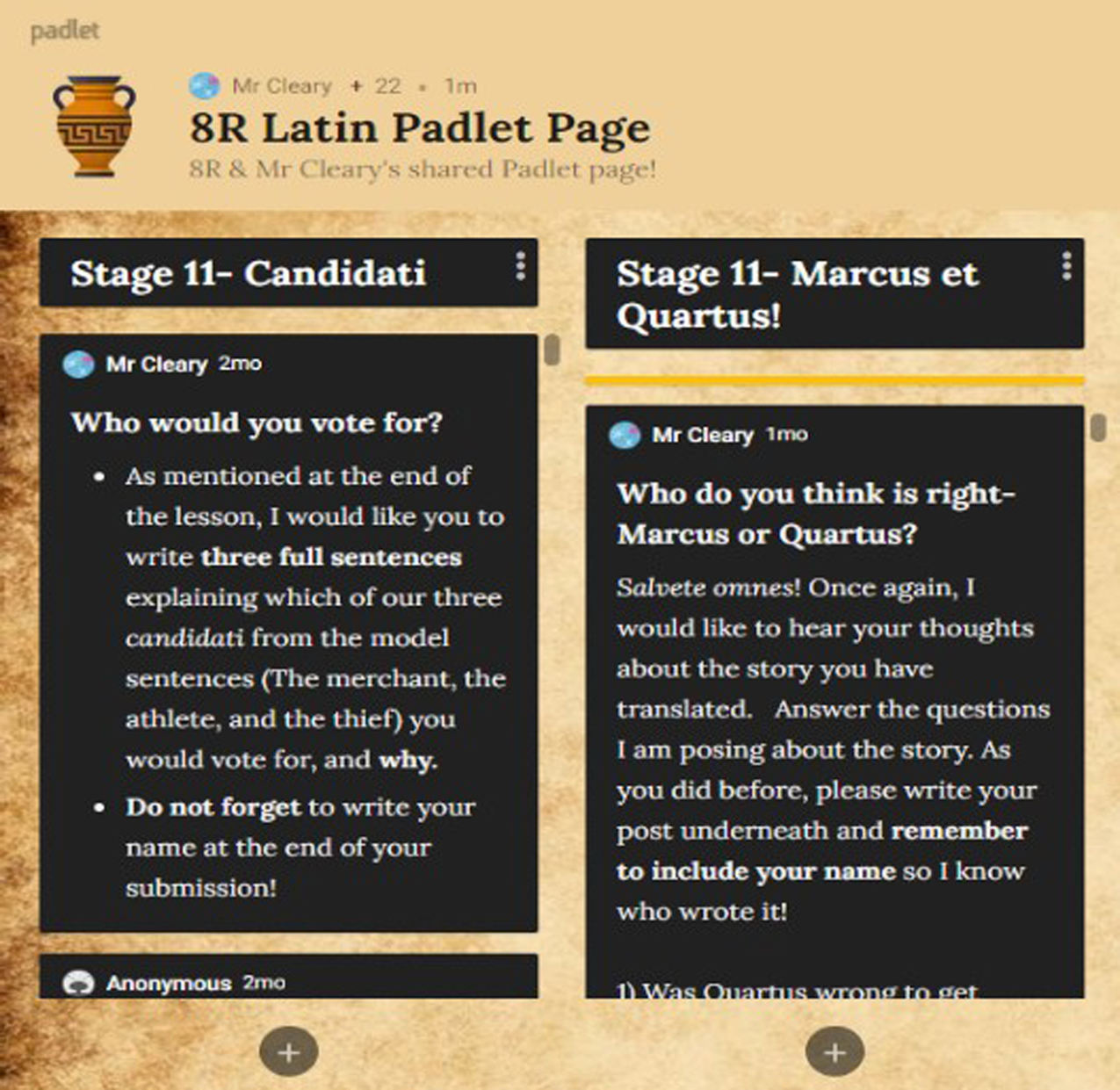

Figure 1 is an example of the way in which I conducted feedback on the students’ Padlet answers. I selected a variety of answers to the questions posed, particularly submissions which contradicted one another in some form. It was noted that all students were engaged when set on the task of reading and then discussing the answers displayed on the screen, and often considered the question at hand in greater depth than I had initially anticipated. In Figure 1, for example, one student responded to the question ‘Who do you think won the argument in the end? Marcus, Quartus, or someone else?’ by stating that the story itself was a message about how ‘revenge may not always be the answer’. Clearly, these questions were encouraging the class to ponder and consider the narrative behind the story, using their comprehension of the Latin story to supplement their responses.

Figure 1. Padlet answer class feedback example.

The questions I posed to the students on the Padlet page (see Figure 2) were often open-ended in nature, as I wished to experiment with how the Padlet platform can help teachers to provide a holistic learning experience beyond the Latin language and grammar introduced in each Stage. As Hunt notes, ‘the teacher needs to vary the activities between and even within lessons to accommodate most of their students’ cognitive styles’ (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, 72). The discussion-based nature of my feedback was intended to counter-balance the language-heavy element of my teaching when exploring the Stage's stories, furthering their learning and understanding.

Figure 2. The Padlet page students accessed during the research project.

My observations of student engagement with the Padlet platform within and beyond our lessons encouraged me to initially believe that it was well received by the class. The quality of their submissions was very high, and the feedback discussions which took place during our ‘live’ lessons contributed to and furthered student learning.

Self-Completion Questionnaire

The set-up and completion of the student questionnaire (see Supplementary Appendix) was conducted following the completion of my research lessons, and was designed to give students the opportunity to relay their opinions and experiences of using the Padlet platform. This was completed in person following the students’ return to school. Of the 30 students in the class 27 completed the questionnaire, with the remaining three choosing not to take part which I explained was perfectly acceptable. I will discuss interesting responses to each question, recurring themes I have discovered in the class's answers, and hypothesise to what extent they assist me in better understanding their opinions on Padlet and its use during the online learning period.

One of the most striking observations I made after reading and reflecting on the class's surveys was the frequent mentioning of the anonymity Padlet offers students when submitting their answers. I was still able to see who submitted the post, but their identity would be hidden from all other students. One student (Daphne in the focus group interview) commented ‘I really like that all the responses are/can be anonymous if you want as it helps getting your point across without being spotlighted’. I found the use of the verb ‘spotlighted’ particularly interesting, as I believe this conjures up an imagery of being ‘put on the spot’, perhaps indicating that this was something which made this student particularly nervous. Another student (Juno in the focus group interview) stated that ‘no one except the teacher could see [our answers] so I think I thought about the questions more and was more honest’. This is a particularly interesting revelation, as it suggests to me that my decision to allow for anonymous posting gave this student the confidence to express their opinions without fear of criticism from other students, in addition to making them ‘think about the questions more’ which I had not anticipated.

Another interesting pattern I observed in students’ responses within the questionnaire was the desire to change the way in which feedback on Padlet answers was delivered in the lesson. For example, Juno, in response to the question ‘If there was one thing you could improve about the way we used Padlet over the remote learning period, what would it be and why?’ noted that ‘It would be nice if the teacher could tell us the ways we could improve our answers’. I found this particularly intriguing as the use of the word ‘improve’ here implies that Juno believed that their Padlet submissions were being quality-assessed, despite my assurances that there was no ‘right or wrong’ answer and that I simply wanted to gather student opinions on the stories we covered in class. This could also, however, reflect a desire to develop their critical thinking skills and ability to articulate their thoughts effectively, something Latinists have championed as a core benefit to the study of the ancient world in the modern classroom (see Holmes-Henderson et al., Reference Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018). Hunt states that ‘inflected languages like Latin and Greek offer special opportunities for the cultivation of critical thinking skills’ in the demand it places upon the learner to make judgements about the order and composition of their translations (Hunt, Reference Hunt2016, 232). Therefore, Juno's desire for improvement of their answer may hint at a further opportunity for Latin to cultivate students’ critical thinking skills through digital platforms such as Padlet.

I will conclude my discussion of my findings from the self-completion questionnaire by analysing the quantitative data collected from the survey. Within the survey, I made use of two Likert scale questions, in order to gather holistic data on student experiences using Padlet over the learning period. The first scale asked ‘on a scale of 1-10, how much have you enjoyed using Padlet in class?’, and the second asked ‘If we ever needed to return to the remote learning period again, how keen would you be to make use of Padlet in our Latin lessons again?’.

I intentionally positioned these measures at the beginning and end of the survey, as the first question gathers a general consensus on the Padlet platform from the class and the second Likert scale asks students to consider Padlet’s effectiveness in the remote learning period through a hypothetical return to remote learning. Therefore, students would answer this second Likert scale question having considered the benefits and setbacks of the Padlet platform in the previous questions. The results of the two Likert scales are listed below in Figures 3 and 4:

Figure 3. Student responses to Likert Scale question 1. Average score: 7 (7.3)

Figure 4. Student responses to Likert Scale question 2. Average score: 7 (7.4)

The results of these Likert scale questions are very revealing. First of all, students answered more positively to the question asking if they would want to use Padlet again in a hypothetical second remote learning period in Figure 4 than Figure 3 surveying their experiences of Padlet. Despite this, the difference in each scale's average score is minimal. From these results, I argue this indicates that students see more potential in the use of Padlet in learning than we had made use of, further demonstrating the relevance and importance of this paper. This was a finding I kept in mind for the focus group interview.

Another possible avenue of further questioning I could gather from these Likert scale questions was the fact that one student had opted to circle ‘2’ in the two measures. In order to keep my conclusions balanced and reasonable, I made sure to include this student in the focus group interview (Persephone), as this student clearly did not enjoy using the platform and I wished to discover why this was the case. While it is pleasing to see that this student felt comfortable enough to be completely honest in their responses, suggesting that the risk of ‘acquiescence response bias’ which a questionnaire such as this holds had not taken effect (Lavrakas, Reference Lavrakas2008, 3), this student's response also presents the opportunity to discover the limitations of my implementation of Padlet within my research lessons. This was therefore a key component of achieving my research objective of exploring the ways in which digital platforms can be used by teachers in order to generate and best capitalise on learning opportunities within and beyond the classroom.

The self-completion questionnaire I used in this research project was enlightening in a number of ways. Firstly, it revealed to me that I was correct in anticipating that the anonymity the Padlet platform offers would be the most memorable feature to the students, and this finding offers many exciting ideas as to how teachers might tackle factors which contribute to low participation levels in the classroom (such as social anxiety). Another interesting discovery was the mixed reception to the ways in which feedback was delivered, with many students wishing to improve their answers upon reflection. This made me consider to what extent digital platforms can function as more than simply an auxiliary tool for classroom learning, but also as an opportunity to develop students’ critical thinking skills through the platform. This demonstrates the importance of the focus group interview, where I could analyse these questions in greater depth.

Focus Group Interviews

In total, nine students were invited to take part in a further group interview to discuss their answers to the Padlet questionnaire. I returned each student's Padlet survey to them prior to commencing the interview, as I had explained that they had been chosen purely on the basis of their answers and I wanted them to have a point of reference when answering the interview questions. I operated a ‘hands-up’ approach to answering my questions, where students would raise their hands if they would like to contribute an answer. This was to avoid ‘forcing’ answers out of the focus group and keep my data as authentic as possible. However, each student offered a one sentence summary of their experiences of using Padlet over the remote learning period which can be found in Figure 6.

Below, I have listed the questions posed in the focus group interview in chronological order:

Topic 1: Anonymity

What are your thoughts on your Padlet answers being anonymous?

Did the fact that your Padlet submissions were anonymous impact the way you chose to answer in any way? Why?

Topic 2: Feedback

What do you think about the ways in which feedback was delivered in our live lessons?

Would you have preferred a different means of feedback of your Padlet submissions? If so, what would that be?

Topic 3: General Experience

Can you summarise your experience of using Padlet over the remote learning period in one sentence?

I have recorded student responses in a journal, and I will refer to this throughout this section. Figure 5 shows how each student answered the two Likert scale questions in the Padlet questionnaire:

Figure 5. Focus group interview data.

Although the focus group's response to the Likert scale is not particularly varied (averaging a score of 7 in both questions), the written responses they made provided suitable springboards for further investigation. I will now discuss the most interesting aspects of the focus group discussion, and what it reveals about the student experience of online learning both through Padlet and beyond.

Topic 1: Anonymity

There was a mixed response to the questions posed in the first portion of the focus group interview. When asked what they thought about Padlet's anonymous feature, Vesta mentioned that she felt less ‘pressured’ to appear as if they had the perfect answer, and had more ‘freedom’ in their submission. This correlated with her self-completion questionnaire where she wrote that ‘I had to think more about what I'd learnt’ to answer the questions which ‘were interesting and had many different answers you could give’. On the other hand, Ceres admitted that she had not consciously considered the fact that their answer was anonymous due to the fact that I (as their teacher) could see who wrote each submission, and therefore the anonymous feature did not impact the way they chose to answer the questions. I had not initially considered how the lack of ‘pure’ anonymity might essentially defeat the purpose of the anonymous feature, as the implicit pressure of having a teacher reading your work has not been removed. This led me to consider to what extent my research project could be taken further by creating an environment in which ‘pure’ anonymity can be achieved, and gauge from this study to what extent this alters the student approach to submitting their answers.

Overall, I gathered from the focus group interview that the anonymous feature was a controversial one. While some saw it as an opportunity to avoid being ‘spotlighted’ (Vesta, Venus, Daphne), others found it ineffective in its purpose of removing the implicit pressures associated with contributing to classroom discussions in person such as the desire to ‘impress’ your teacher (Ceres, Flora). Therefore, I must argue that although the anonymous feature sets a precedent for renewing the ways in which students are able to contribute to discussions in and beyond the classroom, it is not a ‘perfect’ solution and there will simply always be other factors influencing student behaviours in the classroom.

Topic 2: Feedback

It became clear that the ways in which Padlet had been discussed in class and feedback on student answers was delivered could have been improved, according to the students., Flora for example, expressed her frustration at the fact that they could not see other students’ answers before submitting her own. Indeed, in their questionnaire, they state that they ‘like to learn with the class’.

This revealed to me that what I had initially anticipated would be of benefit to students (submitting an answer without being influenced by other students) had not been received this way by some members of the class. This is an important revelation: crucially, collaborative approaches enable all students to take part, rather than a minority of students who are confident enough to offer contributions to the class. Perhaps, had I taken the opportunity to employ the tools Padlet offers for collaborative learning (such as commenting on posts), I may have developed their critical thinking skills in a more efficient manner. Certainly, it cannot be denied that the remote learning period isolated students from one another; with this in mind, upon reflection of this focus group interview and their experiences of remote learning, I believe it would have been more beneficial for the students to introduce an element of collaboration to the digital platform by allowing them to debate and discuss each other's answers on the platform itself.

What can be concluded from the students’ discussion of my chosen feedback methods is the value students place in collaborative and communicative approaches to delivering discussion-based activities in the remote learning period, and the potential this holds to combat the undeniable isolating factor which accompanied online learning.

Topic 3: General Experience

Figure 6 highlights how each student responded to my request to summarise their use of Padlet in one sentence, which I noted in my journal:

Figure 6. Student summaries of their experiences using Padlet

We can infer from the students’ summaries of their experiences that overall Padlet was seen as an easily accessible platform (Juno, Flora). I believe this was due to both the very careful instructions I issued to the students when assigning the Padlet tasks, as well as the increased accessibility digital platforms enjoy, such as through phone apps. What also appears to remain a core component of student experiences of using Padlet is the way it impacted the students’ engagement with Stage 11's various stories. As Barnes states, ‘Speech, whilst not identified with thought, provides a means of reflecting upon thought processes, and controlling them’ (Barnes, Reference Barnes1976, 98). In this way the dissection of Stage 11's stories into its core narrative components, and subsequent debate through Padlet submissions, benefitted students by having them reflect upon both what they know about the text and how this information was gathered - a nuanced and innovative approach to assessing student comprehension which certainly rises to the challenge online learning has posed.

Conclusions

In summary, the data I have collected over the research period has led to some interesting findings. The sequence of my data collection allowed me to gather information with an increasingly acute lens, beginning with an assessment of student experiences using Padlet holistically through the self-completion questionnaire and concluding with a detailed dissection of this with a select group of students. As a result, I have come to a number of conclusions:

Conclusion 1: Students see potential in the Padlet platform, but feel it could have been used more effectively in class.

Conclusion 2: Collaborative and communicative approaches to discussion-based activities are highly valued by the students.

Conclusion 3: Although certain factors affecting a student's likelihood of participating cannot be remedied, the anonymous feature is valued by the students for the freedom it provides.

Conclusion 1 was drawn upon reflection and discussion of the ways in which feedback was delivered in our ‘live’ lessons. Conclusion 2 originated from the focus-group interview, and Conclusion 3 came from a combination of my own observations and the two subsequent surveys of student experiences I conducted. I will now discuss my recommendations for future research, and finish with a comment on the possible implications of this paper's findings.

Recommendations for Future Research

Further research into student experiences during the remote learning period is vital for reviewing standard teaching practice for a post-pandemic learning environment. As previously mentioned further research is currently being conducted on the remote learning period, and through this I hope we can better understand (and remedy if required) the impact of online learning on young people's education. There is certainly scope to research different digital platforms and their possible advantages in a blended learning environment, such as Future Learners and Stormboard¸ and through this research I believe teachers can spearhead pedagogical innovation through the successful implementation of digital platforms into everyday learning.

A suggestion I would make for setting the parameters of this future research would be to keep the student voice at the centre of the project. Throughout this paper, I have discovered that the student voice is more than simply an alternative data collection method when published studies are limited (as was the case in an emerging field such as this). Having students articulate their experiences of remote learning in this project illuminated flaws in my research conduct and revealed possible solutions to questions I had not initially anticipated. Therefore, I would recommend keeping the student voice at the forefront of any future project on a similar topic in order keep it both relevant and informed. It is the students, after all, for whom this research is ultimately being completed.

Final Thoughts

It is my hope that this paper has demonstrated that digital platforms certainly do have a role to play in future teaching, particularly if we ever need to return to online learning again. With questions being raised as to what role online learning will play in the future of education (GovindaraJan et al., Reference Govindarajan and Srivastava2020), I believe this paper will prove to be one of many studies looking toward the digital world in order to reassess how teachers can provide the highest standard of education for their students and make the most of every learning opportunity which presents itself. In terms of my own professional development, my teaching practice has certainly been improved as a result of conducting this project. My ability to adapt teaching resources and use them with versatility has been heightened, and the project reminded me of the importance of listening to students as they describe their experiences and express their learning needs. Ultimately, I am looking forward to observing how the remote learning period will affect and evolve teaching practice as we enter a post-pandemic learning environment, which I hope keeps digital platforms such as Padlet in mind.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2058631022000150