Introductions

‘In 1986 we should no longer settle for books that present women as almost invisible entities.’

(Charlayne Allan, 1986, p.6).Charlayne Allan's conclusion in her 1986 work, ‘Images of Women’ calls for a transformation in the inclusion and presentation of women in Classics educational materials. However, 33 years later, the presentation of women in educational textbooks remains a prevalent issue in many countries today with slow progress being made (BBC, 2017). The discipline of Classics has been criticised for being particularly slow in addressing the issue of gender bias in textbooks, both ensuring that there is a female voice in educational materials and also responding to female scholarship (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.86). There has been some criticism of the popular and widely-used Cambridge Latin Course with the suggestion that ancient women are not equally or fairly represented through the characters and storylines used in the textbooks (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006; Upchurch, Reference Upchurch2013). The course was first written in the 1970s and so, perhaps understandably, lacks strong female characters which might suit the engagement of students of the modern world. One solution which has been proposed by the critics mentioned above is the re-designing of the course with a more equal gender balance. However, I am unsure as to whether this is the best way forward. The re-designing of an entire textbook course (and all its online resources, etc.) is a complex undertaking, especially as the CLC has been carefully constructed around a continuous storyline. The creation of female characters, who would have a real significance to students’ learning and understanding of the Roman world, cannot simply be added into the stories without significantly changing the course (Joffe, Reference Joffe2019). Moreover, the way in which women are depicted in the CLC should not merely be a numerical matter. Consideration of how best to accurately present and teach students about the experiences of women in the Roman world, bearing in mind the Roman patriarchal way of thinking, could be endangered to achieve a mathematical solution for gender balance. The success of the CLC is largely down to its popular storylines and characters and so, for the purposes of my research, I will focus on the balance between the importance of an engaging storyline and at the same time, ensuring that the lives of ancient women are accurately presented through the female characters.

Therefore, I decided to carry out my own research into this issue to see if students’ perceptions could offer useful and new insights into alternative ways forward. I have chosen to focus on the CLC for two main reasons: firstly, this is the most popular course used to teach Latin at secondary schools in the UK, and secondly, this course is followed at my placement school. Reading the work of critics like Churchill and Upchurch on gender bias within Classics on my teacher-training course coupled with the opportunity to work at an all-girls’ school, helped to form my research focus on examining students’ perceptions of women (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006; Upchurch, Reference Upchurch2013). I conducted my research at an all-girls’ selective grammar school which offers Latin across all key stages. In Year 7, Latin is compulsory for all students with one hour a week on the timetable and students follow the CLC up to Book IV, which they start at the end of Year 10. Students at my placement school had significant opportunity to become familiar with the characters and their storylines as the department prioritised ensuring students had time to explore every Latin story and background information in the textbooks, rather than rushing through them purely for linguistic purposes. Consequently, the nature of how the course was taught in the school confirmed my research focus on students’ perceptions of characters and their storylines. Before discussing my methodology and then presenting my findings, first I shall discuss both the wider and subject-specific literature relevant to the title of my study which I have briefly mentioned here in my introduction.

Literature Review

Discussion surrounding how to ensure that learning environments are wholly inclusive for all students has been highly topical in recent years. Therefore for the purposes of this research, I would first like to acknowledge the complexity of the debate surrounding inclusion in education and emphasise how I will be focusing on just one aspect of this important discussion: gender issues in education. More specifically, my research examines how gender is presented in educational materials used in the classroom and how this can impact upon students’ learning. The focus of my research is on the presentation and inclusion of women in textbooks; however, I will also consider the presentation of men when appropriate to my argument and analysis. Although this may be not appear to be the most pressing matter in education today, how gender is presented in materials which are used regularly in classrooms can have far-reaching consequences on students’ own understanding of gender. Research suggests that the way in which men and women are presented in educational materials can significantly impact upon and affect students’ perceptions of gender: for example negative stereotypes can be reinforced (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2008, p.346). Furthermore, students may not only develop problematic perceptions of gender, but also the way in which men and women are included in textbooks can seriously impact upon students’ learning ability. This will be discussed further below.

Two key issues of the presentation of gender in educational materials are gender stereotypes and gender bias. These factors can seriously affect students’ perceptions of men and women and Blumberg argues that both gender bias and stereotypes in textbooks are a serious ‘obstacle’ to gender equality in education:

An important, nearly universal, remarkably uniform, quite persistent but virtually invisible obstacle on the road to gender equality in education- an obstacle camouflaged by taken-for-granted stereotypes about gender roles. (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2008, p.346)

Blumberg summarises here the key characteristics of the problem of gender presentation, which I will now discuss further. Firstly, Blumberg highlights the urgency of the issue by suggesting it is a consistent problem affecting education worldwide. This was revealed in a report by UNESCO in 2016 which examined educational materials across a number of geographical areas and subjects and concluded that gender bias and stereotypes in textbooks are ‘rife’ across the world (The Guardian, 2016). The report also concluded that the presence of gender bias and stereotypes in educational materials undermines ‘girls’ motivation, participation and achievement’ and affects ‘their future life chances’ (GEM Report, 2016). As suggested earlier, there are two key issues here with the presentation of gender in educational resources, which I will now discuss further. Firstly, women are generally under-represented in educational textbooks: in primary English, Hindi, mathematics, science and social studies textbooks in India, only six per cent of the illustrations showed females, while more than half showed only males (The Guardian, 2016). Although limited progress has been made in Europe, North America and sub-Saharan Africa, gender bias is certainly an ongoing issue; a recent survey of science textbooks in the UK revealed that 87% of the characters were male (BBC, 2017). Women are not only under-represented visually in textbooks, but the report also finds that ‘however measured - in lines of text, proportions of named characters, mentions in titles, citations in indexes - girls and women are under-represented in textbooks and curricula’ (GEM Report, 2016). Not only is this a problem because it is an inaccurate reflection of the make-up of our society today, but also research suggests that the non-inclusion of women in materials used to teach female students can seriously impair their ability to learn (Grossman & Grossman, Reference Grossman and Grossman1993).

Secondly, even when women are included in textbooks, they are usually presented negatively along gender stereotypes and this is the other key issue which has arisen from the report. Gender stereotypes can affect both men and women and the report found that men and women were often presented in textbooks in roles and attributed with characteristics which favoured such stereotypes. For example, the GEM report records how in Chinese social studies textbooks all scientists and soldiers were depicted as male while all teachers and three-quarters of service personnel were female (GEM Report, 2016). Not only are men and women depicted in stereotype roles, but they are also presented with attitudes and traits befitting these gender stereotypes. For example, in textbooks used in Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Togo and Tunisia women were portrayed as ‘passive conformists’ and ‘accommodating, nurturing household workers’ while men were engaged in all the ‘impressive, noble, exciting and fun things, and almost none of the care-giving roles’ (GEM Report, 2016). This is highly problematic if textbooks continue to perpetuate such gender stereotypes: ‘It is getting worse by the year, because the world is progressing, women are entering new occupations and household roles are changing … And books are not improving at the same pace, so the gap is widening’ (BBC, 2017). Therefore, textbooks could be in danger of affirming and encouraging rather than challenging misconceptions regarding roles and responsibilities of men and women in society today.

This is a significant problem for a number of reasons: firstly, as outlined earlier, gender stereotypes and bias are a consistent pattern in textbooks worldwide. Although the problem seems most severe in the weakest school systems in the poorest countries, where there is also more likely to be gender-biased attitudes among teachers as well as in learning materials (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2008, p.346), the problem of gender presentation in textbooks does not evade high-income countries either (GEM Report, 2016). For example, the report cites a 2009 study which found that 57% of characters in Australian textbooks were men and there were also double the amount of men portrayed in law and order roles, and four times as many depicting characters engaged in politics and government. Furthermore, the presentation of gender in textbooks specifically is a significant problem, as textbooks are usually the most popular and common educational material used in the classroom by both students and teachers. The GEM Report estimates that textbooks are used as a core means of teaching in 70–95% of classroom time and this is backed by a number of other studies which have concluded with similar results (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2008, p.346). This means that students are potentially interacting with these gender stereotypes frequently and therefore, these textbooks can have a significant impact on the development of students’ own perceptions of gender.

Referring back to Blumberg's summary of the issue, the key difficulty for gender equality in education is the fact that this ‘obstacle’, namely gender stereotypes and gender bias continuing to pervade textbooks, is invisible (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2008, p.346–7). Blumberg suggests that this obstacle is invisible as it has been ‘camouflaged by taken-for-granted stereotypes’ which on the whole continue to be perpetuated across the world. This further highlights how this discussion is part of a much larger debate on the role of gender in our society today. Charlayne Allan's statement, used in the introduction to this research, demonstrates how the issue of gender presentation in textbooks was highlighted in 1986 and yet, there has been limited change. A report made by the BBC commented on how the problem was far from new: ‘Textbooks have been under scrutiny since the 1980s’ and similarly, results from other ‘second generation’ studies, replicating earlier research after two or three decades, find some but very gradual improvement (BBC, 2017; Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2008, pp. 346–7). Blumberg describes any improvement which has been made as ‘excruciatingly slow’ and it is frustrating when significant effort is made to address the gender balance in the workplace, for example, and yet, gender stereotypes are still, inadvertently, being passed onto our students.

This persistence of gender bias and stereotypes has been criticised in Latin textbooks and also more widely across the Classics discipline. Churchill argues in her work ‘Is there a Woman in this Textbook?’ that the teaching of Latin has been especially slow to change to reflect recent changes in demographics, as classrooms increasingly now ‘are more representative of the population as a whole than they were 50, even 25, years ago’ (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.87). Instead, she argues that the teaching of Latin is impaired by gender inequality, as Classics continues to be perceived as an elitist and male discipline (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.87). Latin's historical association as an educational puberty rite for young males has moulded both the curriculum and teaching methods which are designed for the learning style of male students:

Vestiges of gender bias embedded in the history of Latin education persist, however unintentionally and unconsciously, in contemporary textbooks, readers and methods of teaching Latin. (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.88).

As Churchill states, although this continuation of a gendered approach to Latin teaching may often be unintentional, it can have serious implications for female students learning Latin. If textbooks and teaching methods have been designed to suit male students, then the ability of female students to learn Latin can be significantly impaired, especially when considering that textbooks are used for the majority of classroom time, as conveyed earlier. The historical gender bias of Classics as a discipline certainly needs to be addressed much more widely and making a start in the classrooms, where we are educating future Classicists, is certainly one way forward.

Teaching materials are not just simply designed in a style which suits male students of Latin, but the content itself demonstrates that there is also an issue with gender stereotypes and bias in the teaching of Latin. Textbooks used to teach Latin at secondary schools have been criticised for their limited inclusion and negative presentation of women in both the linguistic and historical background sections. Churchill suggests that gender imbalance in Latin teaching materials is often hidden by its disguise as a ‘gender neutral’ subject due to its focus on grammar and syntax and its perception as a ‘dead language’ limited to male-authored texts (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.87); this well could be part of the ‘obstacle’ for Latin teaching (Blumberg, Reference Blumberg2008, p.346). For a start, the Latin curriculum focuses on male-authored texts and this has informed textbooks, even those which aren't specifically teaching a literary text. Textbooks which focus on linguistics (or the grammar-translation approach) have been criticised for a gender bias in their practice exercises, where a female subject would not be culturally incorrect: ‘she can praise the poets, hurry out of the house … quite as well as he can’ (Allan, 1986, p.1). This seems to be less of an issue for the reading courses, such as the CLC (perhaps as female characters are present in a continuous storyline), whereas in linguistic textbooks there is a tendency for practice exercises to continue to reflect the male-dominant themes of the narratives studied in earlier chapters.

Nevertheless, the CLC in particular has received substantial criticism for having the ‘least gender balance’ out of the Latin courses following the reading approach (Latin course books ‘which use a continuous, connected storyline of material specially written for the purpose of teaching the language … [and] to promote reading comprehension’) (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.89; Allan, 1986, p.4; Hunt, 2016, p.38). Firstly, there is a significant gender imbalance in terms of the inclusion of male and female characters in the course; in Unit 1 there are 33 male characters and only three female characters (referring to the American fourth edition of the CLC) (Upchurch, Reference Upchurch2013, p.28). This figure is used as a point of discussion with students in my own research and so will be examined in detail later when my findings are presented. Not only are there only three female characters in this unit, but also these characters do not feature heavily in the stories in comparison to the male characters- in fact, a number of my students struggled to remember Poppaea when trying to name all three female characters. Churchill suggests that this lack of female characters suggests to students that ‘a man's life is at the centre of our concern,’ not only implying that this was case in the ancient world but also that this should continue to be our view today (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.86). Furthermore, the CLC has been criticised for pervading modern gender stereotypes through the characters and the roles that they play in the stories. In general, ‘men and boys are the default category for any display of intelligence, agency, or subversion while women and girls are predominantly compliant and pretty’ (Hoover, Reference Hoover2000, p.59). Allan adds to this, suggesting female characters in Latin textbooks are usually stereotyped as ‘beautiful, usually passive, and often vain creatures’ (Allan, 1986, pp.1–2) and these three adjectives certainly describe some of the female characters in the CLC, in particular Metella and Melissa where vanity and jealousy run central to the storylines involving these two characters. These stereotypes are problematic for two reasons: firstly, they suggest that all women and all men were like this in the ancient world. Secondly, these stereotypes, if not dealt with and discussed openly, can reinforce and encourage students to apply such negative stereotypes to modern society today.

However, Allan makes an interesting point regarding stereotypes with a reminder that gender stereotypes would also have been prevalent in the ancient world (Allen, 1986, p.2). This factor cannot be simply disregarded as the attitudes and values of ancient society can give a greater insight into the lives of men and women. Some textbooks may well be trying to represent such gender stereotypes in the ancient world, but this needs to be clearly portrayed so as to not then either misinform students about the reality of ancient society and equally not reinforce these stereotypes for society today. For example, although men certainly had more ‘active’ roles in the ancient world, there was not a 1:11 female to male population ratio in ancient Pompeii (Upchurch, Reference Upchurch2013, p.28)! This issue brings to light the tension between accurately reflecting the ancient world and at the same time upholding values of today's society. Latin textbooks which are ‘made Latin’ and do not focus on unadapted/adapted passages from Latin authors, like the CLC, arguably are ‘as much a construct of the present as [they are] an artefact of the past’ (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.88). Therefore, should such textbook courses also equally reflect and uphold modern values, such as gender equality, through the characters and storylines they employ? Upchurch questions the purpose of such a balance in her own study of students’ perceptions of female characters in the CLC: ‘Does it matter? Do we seek to give children the most accurate possible view of the Roman world, or to do something else?’ (p. 28). As Hunt points out, the character of Metella in the CLC, who is mostly seen to stay at home and attend to the household, performs actions which would be expected of a woman of her social status in her daily life (Hunt, Reference Hunt2013). However, as Metella and also Melissa are the only ‘main’ female characters of the stories of Unit 1, students could come to view their lives as a representation of the lives of all ancient women.

Churchill calls for a ‘feminist transformation of Latin education’ to tackle this gender imbalance and suggests that educational materials need to make use of feminist pedagogy and scholarship (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.86). She proposes that classroom materials, such as textbooks of ‘made Latin,’ need to be revised to represent more fully women's history; looking at their experiences, roles in society and achievements (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006, p.89). I certainly agree that educational materials need to be developed which offer a more varied and realistic picture of the lives of women (and also men). Churchill suggests that using a wider range of literary and non-literary sources from the ancient, medieval and Renaissance periods alongside feminist scholarship could offer a greater number and variety of texts written by and about women and thus, potentially leading to a greater gender balance. This proposition is certainly attractive and would enrich the learning of Latin. Churchill even suggests that such a development could have the wider recuperation of revitalising Latin (Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006). Teachers, perhaps with the support of textbooks, could certainly include more of a variety of ancient sources in their lessons to enrich the learning of Latin. However, to implement an overhaul in Latin pedagogy, as I believe Churchill is suggesting, would be a major change for the Classics curriculum as a whole and so would need to be part of a much wider debate.

Moreover, I certainly appreciate both the time it takes to create a textbook course and thus, the difficulty it is to revise, especially for courses which are painstakingly structured along a central storyline with consideration of both linguistic and historical elements. Nevertheless, with the number of criticisms of gender imbalance, as well as lack of diversity in other areas, there is certainly an opportunity for a new course. Primarily, the development of a new course would be more suitable than additions to current textbooks which do not necessarily work. Hunt (Reference Hunt2013) and Upchurch (Reference Upchurch2013) both point out the linguistic issue with additions to the American fourth edition of the CLC. In the model sentences of Stage 1, the American fourth edition presents Metella in a more active role: instead of just ‘sitting’ as she was in the previous edition (and still is in the UK fourth edition), Metella is now sitting and pointing out into the garden towards a slave. However, this additional action makes it unclear for students if sedet means to point or sit, as the focal action of the image is now Metella pointing. Therefore, in order to effectively respond to criticism, it is essential that a new course is carefully developed, without women simply ‘added in’. However, in the meantime I think there are options for teachers to organise themselves or opportunities for supplementary materials to be developed alongside textbook courses which aim to provide students with a more accurate representation of women in the ancient world. Researching about the prevalence of gender bias in educational materials worldwide and then examining the issue in further detail within the Classics discipline, helped to inspire and form my own study into students’ perceptions of women. My research takes the form of a questionnaire and group discussion task carried out across three Key Stage 3 and 4 Latin classes in my placement school. I have outlined my research methods and teaching sequence in the methodology section and then, subsequently, have analysed my findings with consideration of possible ways forward to readdress the gender balance.

Methodology

Before I present and analyse the findings of my own research, first I will outline my methodology including the teaching sequence and research methods I decided upon. My study examines the issue of gender bias in textbooks by investigating students’ perceptions of women in the CLC within one school setting. After reading more widely into educational research practice, I found that a case study would be the most suitable approach for the research needed to be conducted for the title of my study. Taking Taber's definition of a case study, my study has identified a complex education phenomenon of gender bias in textbooks and investigates this by examining one particular instance of the issue in detail (Taber, Reference Taber2013, pp. 95–100, 145). For my research I followed an instrumental case study approach:

Where a teacher-researcher selects one class, one lesson, one topic, one group of students, as a suitable context for undertaking theory-direct research, rather than because the issues derives from concerns about that class, topic, etc. (Taber, Reference Taber2013 pp.155–6).

My study explores a ‘general theoretical issue’ in current classroom teaching and learning, for which I selected classes (the reasons behind the selections will be outlined later) rather than choosing the topic of my study because the issue had emerged from those classes (Taber, Reference Taber2013, p.155). The focus of my research is on students’ perceptions and so I wanted to investigate how the identified educational phenomenon played out in my own classes in order to perhaps develop useful and new insights into the issue. Ultimately, I did not want to presume or indeed influence students’ individual observations and opinions, namely I did not want to initially suggest that there was a potential problem with the representation of women in the CLC.

Furthermore, I chose research methods which would be most effective for the type of evidence I wanted to gather in a case study and which would also work well in the environment of the school. I decided to carry out my research using two methods: questionnaire and group discussion. To guide the questions used for each research method, I broke down the broader title of my study into three research questions:

1. What do students perceive the role of women in Roman society to be, from learning Latin with the CLC?

2. What is the range of student responses- how broad is it?

3. What do students think of their own perceptions- do they think there is a difference between the world of the CLC and the Roman reality?

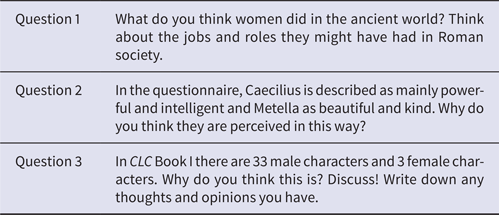

Firstly, I began with an anonymous questionnaire as this allowed me to gather both quantitative and qualitative data, through a mixture of open and closed questions. Secondly, having conducted and read through the responses to the questionnaire, I decided I would continue my research with group discussion questions. Due to time constraints and limitations of the size of the study, I decided to choose three questions based on the questionnaire responses for students to then discuss in groups and write down in a collaborative ‘mind map’ form. I decided to follow an anonymous group discussion format rather than carry out formal, structured interviews for a number of reasons. A group discussion would be more representative of student opinion as it would allow all students who answered a questionnaire to contribute and hopefully, therefore, result in a greater variety of responses.

For my research, I wanted to use classes across the key stages in order to try and achieve the most varied response in student perceptions as possible in the school setting that I was limited to. Moreover, I thought it would be interesting to compare student responses between the key stages and examine whether there was a significant change in opinion as students progressed through the CLC. Initially, I wanted to carry out my research with a year group from each key stage, however I was unable to investigate student perceptions in Key Stage 5 due to the small size of the Latin classes, which would have been difficult to compare to the larger Key Stage 3 and 4 classes. Therefore, I carried out my research with two Year 8 classes and one Year 10 class, and I must also note that the focus of my research is on Books I and III of the CLC, as these were the current books studied by each year group respectively. All three classes I had taught since the beginning of the placement and so felt that they were also the most suitable as I knew the classes well.

As my research did not rely on content or types of activities covered in a specific lesson but rather on student voice and opinion, I did not plan a sequence of teaching lessons. Instead I structured a sequence of lessons around the questionnaire and group discussions I wanted to carry out. I set aside two weeks to carry out my research at my placement school with both Year 8 and Year 10 classes. In the first week I carried out the questionnaires at the start of a lesson for each class. Students were given around 15 minutes to complete the questionnaire, though I was flexible with my timings in order to allow adequate time for students to fully answer all the questions. Before students started answering the questionnaire, I took each class through the questions and added extra explanations where necessary to ensure that all students were confident in what they needed to do. However, I decided to only give a brief introduction to the focus of my research and explained that I was researching student opinion on the characters in the CLC course. My reasoning behind this was that I did not want to pre-empt students’ answers if I revealed that my research was focusing on the perception of women. In the second week, I carried out the group discussion activity in a similar manner to the questionnaire. I arranged each class into groups based on the classroom seating plan: for both Year 8 classes there were six groups with two ‘carousels’ of discussion questions, then for my Year 10 class there were three groups with one carousel. Each table group got approximately three to four minutes to discuss and then write down their ideas and reactions to each question. As with the questionnaire, I introduced the task to the students: I explained that I had analysed their questionnaire responses and decided on three discussion questions which focused on the representation of women. As students discussed the questions, I also circulated around the classroom to make my own written observations and also ensure that students remained focused on the activity.

Findings

In this next section I shall present and analyse my findings from both the questionnaire and group discussion task undertaken by two classes of Year 8 Latin students and one class of Year 10 Latin students (a total of 68 students took part). As I present my findings, I shall also discuss relevant literature when the opportunity arises and begin to offer potential solutions for problems which emerge. I shall also highlight any flaws or anomalies in the results which need to be taken into account when drawing conclusions. Finally, I would also like to emphasise that due to the nature of my sample size, I am only able to draw tentative conclusions in light of the literature which has been discussed earlier.

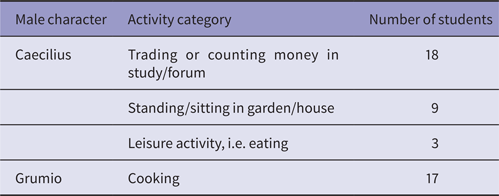

The first part of the questionnaire focused on how students visually perceive the characters in the CLC (see Question 1, Table 1). I analysed the results for this question in two halves: first the selection of characters (students were asked to write the name of the character in a box below their drawing) and then, secondly, the activity chosen for the character to perform. The results for the selection of characters revealed that there was a wider variety of male characters drawn by students (13) in contrast to the number of female characters (five) (Table 3). However, this is surely to be expected considering the smaller number of female characters used in the CLC. For the drawings of both male and female characters there was one character for each which was a clear favourite: nearly half (30) of the students chose to draw Caecilius and over half (48) chose to draw Metella. The second most frequently selected characters were Melissa and Grumio, with 17 students drawing each of these characters. It is interesting that the characters most frequently chosen are all from Book I and all introduced in the first stages, with Caecilius, Metella and Grumio making up the family and household unit introduced in the opening pages of the textbook. Moreover, Caecilius and Metella were both the most frequently selected characters for both year groups and despite only completing Book III in the week before my research took place, more Year 10 students still decided to draw pictures of male characters from Book I over characters they had most recently translated stories about, such as Salvius or Modestus and Strythio. This result suggests that students studying the CLC develop a good understanding of the first characters introduced in Book I. This is especially suggested by the results of the Year 10 questionnaires and reveals that despite last regularly reading about the characters two years ago, students remember them well enough to draw them doing an activity. This strong familiarity with characters indicates the impact of good character writing, which in the CLC seems to last through the course from its initial phases. As I analyse results from other areas of the questionnaires, the familiarity and even fondness for some of the characters in the CLC comes across clearly not only in statistics but also in comments made by the students.

The second part of the analysis of the first question examines the action chosen for each character to perform, which can provide a good insight into the roles students associate with men and women in the ancient world. Due to the variety of actions students have drawn the characters performing, I have grouped the actions for each character when an obvious category has emerged, for example leisure activities. For the purposes of this essay, I will focus on the drawings of Caecilius and Metella, as they were the most frequently selected characters. Firstly, there seemed be a clearer consensus amongst students regarding the duties which male characters performed as there was less of a variety of activities (Table 4). All students who drew Caecilius portrayed him doing one of three action categories (trade, leisure or ‘sitting down’) and similarly, all students who chose Grumio drew him cooking. Students seem to have a firm idea of the types of activities a wealthy, male citizen would have undertaken: either dealing with financial matters or when not doing this, then participating in leisure activities at home. The consensus on the types of activities men would have performed, with consideration of the social status too, again perhaps indicates the level of familiarity students develop with the CLC characters, in particular Caecilius and Grumio who are both introduced in stories in the very first stage.

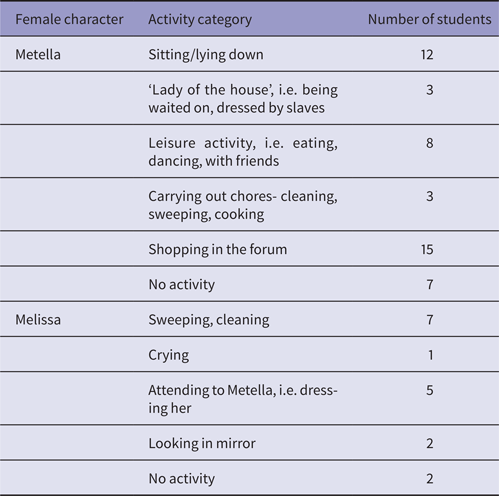

In contrast, students have drawn female characters performing more of a range of activities; however, overall there still seems to be a clear idea among students regarding the roles they might have performed (Table 5). Melissa is mostly frequently drawn as performing one of her duties as a slave, with 12 out of 17 students drawing her as either carrying out a household chore, such as sweeping, or attending to Metella. As with Grumio, students seem to have a clear idea of the sorts of duties slaves would have been responsible for in a Pompeian household. This is perhaps due to the way the CLC introduces slaves: they are included as part of the household in the very first pages of the textbook and they are often the focus of the stories in Book I, with a particular focus on slavery in the ancient world in Stage 6. However, it should certainly be noted that when the family is first introduced in the textbook only male slaves are included (Melissa is introduced in venalicius Stage 3) and Joffe further suggests how students can even develop an inaccurate understanding of the harsh reality of slavery, which is not reflected in the CLC stories (Cambridge Latin Course, 1998, pp.2–5; Joffe, Reference Joffe2019).

There was less consensus on the activities which Metella would have performed, as there was more of a range of responses from the students. Most students depicted Metella performing an activity which would be expected of a wife of a wealthy banker, with the most frequent portrayal of Metella as shopping for a toga or dress in the forum. Another frequent response, linked to the idea of Metella as ‘the lady of the house’, was the portrayal of her enjoying leisure activities such as eating or reading and being attended to by her slaves. It is interesting that a number of students portrayed Metella reading, which I have categorised as a leisure activity, since women were not usually educated and students certainly had been informed of this, having covered Roman education in Stage 10. This perhaps suggests the morphing of modern ideas with the ancient world, which can be seen in other areas of student response. For example, three students depicted Metella performing household chores herself such as cleaning and cooking although these would have usually been carried out by a slave. One student even drew Metella cooking at a modern stove (Appendix 2)! This could suggest students are confusing ancient and modern stereotypes of men and women, and this also could be reinforcing negative stereotypes of gendered roles in society today, such as the role of women in the home.

Furthermore, the second most frequent response for the drawing of Metella performing an activity, was the portrayal of her sitting or lying down - indeed some students even wrote this out beneath their drawing. 12 students portrayed Metella as sitting or lying down and I agree with Upchurch, who received a similar response in her questionnaire, that it is worrying students think simply ‘sitting or lying down’ could be classed as a reasonable activity for Metella to perform on a regular basis (Upchurch, Reference Upchurch2013). I overheard a number of verbal comments from students expressing a similar sentiment and in the group discussion activity, one student wrote the following when describing Metella's role: ‘You don't really know what Metella does other than shopping and sitting.’ However, although Caecilius was also depicted in this manner (nine out of 30 students drew him sitting down as an activity), I would still argue that there seems to be a lack of clarity around exactly what Metella does in the home, especially with seven students failing to draw her performing any activity at all. This is supported by the comments made in response to the second group discussion question which asked students what they thought women did in the ancient world. Most responses to this question commented on women's responsibility for looking after the household, fulfilling their roles as wives and mothers and enjoying leisure activities: ‘They cleaned homes, raised children and had to be dressed for their husband's return in the evenings’. Additional comments included the fact that some women would have been slaves and there were a small number of comments regarding the lives of women of lower social status: ‘Cooking and cleaning (poor women),’ ‘Laundry women,’ ‘Prostitution.’ However, the overall response strongly suggests that students perceive ancient women as having very little status: ‘second class’, ‘inferior’ and who were tied to the household with very little power. This perception is worrying as it implies that students have quite a narrow view of the lives of ancient women, leading them perhaps to believe that what they may learn about the life of a middle-class woman, like Metella, also represents the lives of most other women. This is reflected in the response to Question 4, which asked students if they thought there were any people in Roman society who are not represented in the CLC. Out of the 68 participants, 37 students commented that they felt the ‘lower class’ or ‘poor’ members of society were less represented in the CLC. Only four students specifically commented that they felt women were less represented and in fact more students (11) commented that they would like to learn more about children's lives.

Similarly, the second question in the questionnaire, which asked students to choose three adjectives in English to describe each of the four characters listed (Metella, Melissa, Caecilius, Clemens), reveals some problematic perceptions of women. For both Metella and Melissa, the most popular adjective used to describe them was ‘beautiful’, and was a particularly popular choice for Melissa (Table 6). This supports scholarly opinion that due to gender stereotypes women are usually presented as ‘beautiful’ in textbooks. It's worrying that ‘beautiful’ was the most popular adjective for both women which could suggest that students have interpreted appearance to be one of the most obvious and important ‘characteristics’ of ancient women. In contrast, there was a very clear consensus on the best three adjectives to describe Caecilius: powerful, intelligent and busy. These reflect his status as a wealthy citizen involved in local business and again suggests that students have developed a better understanding of the daily lives of wealthy, male Pompeians.

Moreover, the response to Question 5c (Table 1) reveals students’ familiarity with the male characters: 56 out of the 68 student participants chose a male character as the most interesting, with Caecilius being the most popular choice (21) (Table 7). The most frequent explanation was that students simply knew the most about their chosen male character and therefore, they had found them more interesting: ‘Most of the stories are about him so we know most about him.’ In relation to Caecilius specifically, students commented on how they had found learning about his life interesting as he was ‘the main character’ with an important and powerful role in society. Moreover, students seem to feel more connected to the male characters and invested in their storylines; a number of students commented on how funny they found Grumio, describing him as a ‘loose cannon!’ In contrast, only three female characters were selected, with Metella receiving the highest number of seven, although this is certainly still a low number in comparison to the male characters. A number of comments suggested that students would have liked to have found out more about Metella: ‘Intrigued that all we learn is that she is a mother and wife, what did she do in her spare time?’ A couple of students who had selected Metella commented on the status of women in ancient times and how they had to ‘deal’ with being treated unequally: ‘She's different from the rest of the male figures.’ From their responses, it seems that students want to learn more about the lives of women through the female characters and, being at an all-girls school, the issue of gender equality perhaps especially resonated with the students. This is further reflected in students’ responses to Question 3, which asked students which character they would like to find out more about. Nearly half of the students stated that they would like to find out more about Metella and Melissa, who were the most frequently selected. The next most selected characters were male characters of a lower social status (Clemens, Grumio), whereas only a small number of students chose Caecilius and Quintus.

Furthermore, the response to Question 5c and 3 can be further analysed alongside student responses to Questions 5a, 5b and 5d which focus on gender equality. Students recognised that there is not an equal number of male and female characters in the CLC, with all participants answering ‘no’ to whether they had met an equal number in the textbook(s). In the group discussion activity, students were able to develop their thoughts on the balance between male and female characters in the CLC. Students reacted with shock and disapproval when faced with the fact that there are 33 male characters but only three female characters in Unit 1 of the CLC and there was general agreement that there should be greater inclusion of women in the textbook (Upchurch, Reference Upchurch2013, p.28). A key point raised by students was the difference in status of men and women in ancient society: ‘Not as much gender equality at that time’ and that ‘Women weren't allowed to work, so there were would be more men working, so there would be more male characters as it reflects society in Pompeii.’ Students explained how men had more active roles in society and that with not as many records of women compared to men: ‘Therefore, more male characters featured in the textbook’. A number of groups discussed interpretation problems with the gender balance in the CLC: ‘It shows the ratio of men to women is 11:1 which misleads us to think there were more men’ and so argued that women needed a voice too. Students also recognised the potential difficulties with trying to accurately represent the ancient world with limited sources: ‘Women weren't seen as equals … the CLC book is trying to portray that.’ This sentiment was held by a number of students, who were concerned with the idea of an untruthful reflection of Roman society: ‘Would be lying about their culture’ and reflects the response to Question 5b, where 21 out of 68 students answered ‘no’ to whether they thought it was important to see an equal number of male and female characters. Students’ discussions on this question reveal how they understand that there was a different gender balance in the ancient world and that they trust the CLC to accurately reflect this. However, there is a thin line between understanding that Rome's patriarchal society gave men more prominence and then believing that women led unimportant lives and therefore, not worthwhile of study: ‘There were no interesting stories about them because they only stayed at home or went shopping.’ This was the conclusion a number of students came to when exploring why the CLC had such a character ratio, and suggests that they can apply the lives of the female characters such as Metella, who tends to stay at home or goes shopping in the stories, to women in the ancient world more generally.

Conclusion

My study examining students’ perceptions of women in the CLC has raised a number of interesting points. Firstly, I think my research has revealed that students do perceive female characters in the CLC along gender stereotypes and the overall response suggests that the majority of students perceive the role of ancient women to be inexplicably linked to the home. Therefore, there is a potential problem of students misunderstanding the use of characters in the CLC and trusting them as accurate representations for the whole of Roman society. In particular, the way women are presented and included in the CLC can be misleading; students may leave lessons with the belief that all women were like Metella and Melissa and this could also perpetuate negative stereotypes which society is trying to move away from today. It is apparent, however, that students do recognise that they have learned less about women from the female characters in the CLC and there is a desire to find out more about the lives of women in the ancient world (Question 3). Equally, students’ responses to the questionnaire also indicated that the issue of representation is not limited to just gender, but students were keen to learn more about other members of society less well represented in the CLC, such as poorer citizens, and this perhaps reflects the ongoing discussion for greater diversity in Classics (Barnes, Reference Barnes2018). Another conclusion which can be drawn from my findings is the value of the CLC storyline for both teaching and learning. The level of familiarity students gain with the characters and their stories is unique to the course and can be underestimated, as comments made by students clearly demonstrate how they enjoy the storyline and characterisation. Therefore, I don't think the CLC needs to necessarily be immediately overhauled when there are other ways of including greater female representation in the short term. Indeed, what can be seen as a negative gender imbalance in the CLC could be used positively as a starting point for a greater discussion about Roman patriarchal values and wider research into the lives of women looking at a greater variety of ancient sources in lessons, as suggested by Churchill (Joffe, Reference Joffe2019; Churchill, Reference Churchill and Gruber-Miller2006). This would allow for inaccurate perceptions of women's lives in the ancient world, based on the CLC characters to be addressed and would challenge students to explore wider historical and modern issues regarding diversity.