1. Introduction

Vietnamese is the fifth most widely spoken non-English language in the world (Dao & Bankston, Reference Dao, Bankston and Potowski2010) and the third most frequently spoken Asian language in the United States, used by approximately 2.2% of individuals whose primary language is not English (Shin & Kominski, Reference Shin and Kominski2010). The Vietnamese stop inventory includes nine stops, among which are three alveolar phonemes /d/, /t/, and /t̪ʰ/. It is well established that stop consonants are among the earliest developing speech sounds in children (Arlt & Goodban, Reference Arlt and Goodban1976; Crowe & McLeod, Reference Crowe and McLeod2020; McLeod & Crowe, Reference McLeod and Crowe2018; Prather et al., Reference Prather, Hedrick and Kern1975; Smit et al., Reference Smit, Hand, Freilinger, Bernthal and Bird1990). A cross-linguistic review of 27 languages found that most stops are acquired between 36 and 47 months of age, with the exception of some rare stops (i.e. /kwh, tʕ/) which are typically acquired between 48 and 49 months (McLeod & Crowe, Reference McLeod and Crowe2018). As in other languages, stop consonants are acquired early by Vietnamese-speaking children. Among the three alveolar stops, /t/ and /d/ are typically acquired by around 4 years of age, while the voiceless aspirated stop /t̪ʰ/ develops between 5 years and 6 months (5;6) to 6 years of age (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nguyen Phuoc, Truong Thi, Dang Thi, Ho Thi and Ha2024; Phạm & McLeod, Reference Phạm and McLeod2019).

Previous studies on speech acquisition in Vietnamese children have primarily relied on perceptual assessment. While the development of stop consonants has been examined acoustically in languages such as English, Spanish, Korean, Thai, and Hindi (Davis, Reference Davis1995; Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986; Kim & Stoel-Gammon, Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009; Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980a, Reference Macken and Barton1980b; Tyler & Saxman, Reference Tyler and Saxman1991; Zlatin & Koenigsknecht, Reference Zlatin and Koenigsknecht1976), no such acoustic studies have been conducted in Vietnamese-speaking children and only a limited number are available for Vietnamese-speaking adults. Among various acoustic measurements used in analyzing stop production, voice onset time (VOT) has been widely recognized as a key indicator of voicing contrast (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Whalen and Docherty2019). Acoustic analysis can offer critical insights into the precise timing coordination between supralaryngeal and laryngeal movement in Vietnamese children when producing different voicing categories. Although a previous perceptual study (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nguyen Phuoc, Truong Thi, Dang Thi, Ho Thi and Ha2024) found that some Vietnamese children as young as four produced /t̪ʰ/ correctly, it remains unclear whether their productions involved the same articulatory gestures as those of adults, given the inherent limitation of perceptual assessment. Therefore, an acoustic study examining stop production in both Vietnamese children and adults is essential to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how voicing contrasts are realized and develop in Vietnamese.

1.1. Voice onset time and voicing contrast development

VOT – the interval between the release of the stop and the onset of voicing – is a widely used acoustic parameter for characterizing stop categories across languages (e.g. Barton & Macken, Reference Barton and Macken1980; Cho et al., Reference Cho, Whalen and Docherty2019; Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986; Kim & Stoel-Gammon, Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Beckman and Edwards2012; Lisker & Abramson, Reference Lisker and Abramson1964; Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980b; Millasseau et al., Reference Millasseau, Bruggeman, Yuen and Demuth2021; Ohde, Reference Ohde1985; Zlatin & Koenigsknecht, Reference Zlatin and Koenigsknecht1976). Cho et al. (Reference Cho, Whalen and Docherty2019) grouped languages into three categories based on the number of stop contrasts: two-way, three-way, and more than three-way contrasts. Languages with a two-way contrast were further subdivided into “aspirating” and “true voicing” types. In aspirating languages (e.g. English and German), voiced stops are typically produced with short-lag VOT, while voiceless stops have a long-lag VOT. In contrast, true voicing languages (e.g. Spanish and French) featured voiced stops with voicing lead and voiceless stops with short-lag VOT. Languages with a three-way contrast, such as Vietnamese and Thai, exhibit a more complex pattern: voiced stops are produced with a long voicing lead, voiceless unaspirated stops with a short-lag VOT, and voiceless aspirated stops with a long-lag VOT.

Previous research has shown that differences in VOT between stop categories emerge in English-speaking children between 18 and 30 months of age (Kewley-Port & Preston, Reference Kewley-Port and Preston1974; Lowenstein & Nittrouer, Reference Lowenstein and Nittrouer2008; Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980a; Snow, Reference Snow1997; Tyler & Saxman, Reference Tyler and Saxman1991; Zlatin & Koenigsknecht, Reference Zlatin and Koenigsknecht1976). Kewley-Port and Preston (Reference Kewley-Port and Preston1974) hypothesized that short-lag stops are easier for children to articulate and control than long-lag and voicing lead stops. Macken and Barton (Reference Macken and Barton1980a) examined VOT development in four English-speaking children aged 1;4 to 1;7 and proposed three stages of voicing contrast acquisition. In the first stage, both voiced and voiceless stops were produced with short lag VOTs. In the second stage, a significant VOT difference between voiced and voiceless stops emerged, but the VOT values remained non-adult like. In the third stage, voiceless stops were initially produced with exaggerated VOTs beyond adult norms but decreased to approximate adult values. Hitchcock and Koenig (Reference Hitchcock and Koenig2013) found similar developmental patterns in 10 children aged 27–29 months, particularly the early-stage overlap between voicing categories and the later-stage exaggeration of VOTs for voiceless stops.

In non-English languages, the developmental trajectory of voicing contrast varied due to linguistic differences (Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986; Kim & Stoel-Gammon, Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009; Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980b). Macken and Barton (Reference Macken and Barton1980b) studied seven Spanish-speaking children aged 1;7 to 4;0 and found that five of them showed no significant VOT difference between voiced and unaspirated voiceless stops, even at ages 3–4. The remaining two children showed a significant contrast only between /p/ and /b/. In Thai, which features a three-way voicing contrast (voiced, voiceless unaspirated, and voiceless aspirated stops at bilabial, alveolar, and velar places), Gandour et al. (Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986) reported that while 3-year-old children showed some evidence of voicing contrasts, the distinction between voiced and voiceless unaspirated stops (/p/ vs. /b, /t/ vs. /d/) was not clearly established. Significant overlap in VOT values between these categories persisted even in 5-year-old children.

Kim and Stoel-Gammon (Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009) investigated Korean-speaking children aged 2;6 to 4;0, focussing on the language’s three-way stop contrast: lenis, fortis, and aspirated, produced at labial, alveolar, and velar places. At age 2;6, children produced longer VOTs for aspirated and lenis stops than for fortis stops, although the difference between aspirated and lenis stops was not significant. By age 3;0, children demonstrated significant VOT differences across all three categories. At ages 3, 6, and 4, 0 significant contrasts were observed at the labial place, but VOT differences between lenis and aspirated stops at the alveolar and velar places remained nonsignificant. The authors also noted that, in addition to VOT, the fundamental frequency at vowel onset (hereafter vowel onset F0) played an important role in distinguishing between the two long-lag stops (lenis and aspirated).

1.2. Fundamental frequency at vowel onset

Although VOT is typically the primary parameter used to distinguish stop categories, it may not capture all the acoustic features of voicing contrasts, particularly in languages with more than two stop categories. The effect of voiced and voiceless stops on vowel onset F0 has been well documented in previous studies. Among English speakers, vowel onset F0 following voiceless stops was significantly higher than following voiced stops (Ohde, Reference Ohde1984, Reference Ohde1985; Oh, Reference Oh2019). This pattern has also been observed in other languages (Dmitrieva et al., Reference Dmitrieva, Llanos, Shultz and Francis2015; Kong et al., Reference Kong, Beckman and Edwards2012; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Chen and Mous2020). The effect of voicing on vowel onset F0 has been explained by the aerodynamic and vocal fold tension hypotheses (Hombert et al., Reference Hombert, Ohala and Ewan1979; Ohde, Reference Ohde1984). During the production of voiceless stops, increased negative pressure in the glottis leads to more rapid adduction of the vocal folds, resulting in a higher vowel onset F0. Additionally, while vocal folds are slackened to facilitate vibration during voiced stop production, they are stiffened to inhibit glottal vibration during voiceless stop production. This stiffening carries over into the following vowel, contributing to the higher vowel onset F0 after voiceless stops compared to voiced stops.

While the effect of voiced versus voiceless consonants on vowel onset F0 has been consistently reported, the difference in vowel onset F0 between aspirated and unaspirated stops remains controversial. Several studies (e.g. Han & Weitzman, Reference Han and Weitzman1970; Hanson, Reference Hanson2009; Jeel, Reference Jeel1975) have reported a higher vowel onset F0 following aspirated stops compared to unaspirated stops. This can be attributed to the greater airflow during the production of aspirated consonants, which causes more rapid adduction of the vocal folds, resulting in a higher F0 (Hombert et al., Reference Hombert, Ohala and Ewan1979). However, other studies have observed the opposite pattern – a higher vowel onset F0 following unaspirated stops – in languages such as English (Ohde, Reference Ohde1984, Reference Ohde1985), Thai (Gandour, Reference Gandour1974), Cantonese (Francis et al., Reference Francis, Ciocca, Wong and Chan2006), and Mandarin (Xu & Xu, Reference Xu and Xu2003). Xu and Xu (Reference Xu and Xu2003) proposed that increased subglottal pressure at vowel onset following unaspirated stops, compared to aspirated stops, leads to higher transglottal pressure, which, in turn, results in a higher vowel onset F0 after unaspirated stops. These inconsistent findings highlight the need for further research in languages with the aspirated/unaspirated contrast to clarify these patterns.

1.3. Changes of VOT and vowel onset F0 during the developmental period

Acoustic studies have provided evidence that stop production continues to develop and refine beyond the age at which perceptual acquisition is achieved. Previous research has shown that English-speaking children produced significantly longer VOTs than adults (e.g. Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986; Kent & Forner, Reference Kent and Forner1980; Millasseau et al., Reference Millasseau, Bruggeman, Yuen and Demuth2021; Ohde, Reference Ohde1985; Yu et al., Reference Yu, De Nil and Pang2015; Zlatin & Koenigsknecht, Reference Zlatin and Koenigsknecht1976). However, by 12–18 months of age, children’s VOT values began to approximate adult norms. Similar development trends have been observed in other languages. For example, although significant differences in the VOT values of /b/ and /d/ were found between Thai-speaking children and adults, children aged 7 produced VOTs comparable to those of adults (Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986). Children exhibited greater VOT variability than adults, even after their stop productions became perceptually acceptable (Kent & Forner, Reference Kent and Forner1980; Koenig, Reference Koenig2000; Ohde, Reference Ohde1985; Whiteside et al., Reference Whiteside, Dobbin and Henry2003; Yu et al., Reference Yu, De Nil and Pang2015).

Compared to VOTs, fewer studies have investigated the difference in vowel onset F0 and F0 variability between children and adults. Kim and Stoel-Gammon (Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009) found that the absolute values of vowel onset F0 in Korean-speaking children were higher than in adults. In a study of voiceless stop production involving 10 participants aged 4–21, Robb and Smith (Reference Robb and Smith2002) reported that the rising vowel onset F0 in 4-year-old children was lower than in adults. Other studies have shown a general decrease in overall F0 from early childhood to the onset of puberty, although these studies measured overall F0 rather than vowel onset F0 (Kent, Reference Kent1976; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Potamianos and Narayanan1999; Whiteside & Hodgson, Reference Whiteside and Hodgson2000). As with VOT variability, F0 variability has been found to decrease consistently with age, likely reflecting the maturation of speech-motor control (Kent, Reference Kent1976; Kim & Stoel-Gammon, Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Potamianos and Narayanan1999; Ohde, Reference Ohde1985; Whiteside & Hodgson, Reference Whiteside and Hodgson2000).

1.4. Sex difference in VOT and vowel onset F0

Previous studies on sex differences in VOT among both adults and children have produced mixed results. Some studies found that females exhibit significantly longer VOTs than males (Ryalls et al., Reference Ryalls, Zipprer and Baldauff1997; Swartz, Reference Swartz1992; Whiteside & Marshall, Reference Whiteside and Marshall2001), while others have reported either the opposite pattern or no significant sex differences (Koenig, Reference Koenig2000; Morris et al., Reference Morris, McCrea and Herring2008; Oh, Reference Oh2019; Sweeting & Baken, Reference Sweeting and Baken1982; Whiteside & Irving, Reference Whiteside and Irving1998; Yu et al., Reference Yu, De Nil and Pang2015). Regarding vowel onset F0, only one study (Robb & Smith, Reference Robb and Smith2002), which included 10 participants aged 4–21, investigated sex differences and found that adult females had higher vowel onset F0 than males. Additional studies examining overall F0, rather than vowel onset F0, have also reported higher F0 values in females compared to males (Harries et al., Reference Harries, Hawkins, Hacking and Hughes1998; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Potamianos and Narayanan1999; Whiteside & Hodgson, Reference Whiteside and Hodgson2000). These inconsistent findings highlight the need for further research with larger samples across different age groups to clarify these patterns.

1.5. Acoustic characteristics of the voicing contrast in the Vietnamese language

A few previous studies have investigated the acoustic manifestation of the voicing contrast in adult Vietnamese speakers (Carne, Reference Carne2008; Kirby, Reference Kirby2018; Vu, Reference Vu1981). Kirby (Reference Kirby2018) examined 14 adult speakers of Northern Vietnamese, aged 29–58, and reported the mean VOTs of voiced stop /d/, voiceless unaspirated /t/, and voiceless aspirated /t̪ʰ/ in isolated words as −60 ms, 14 ms, and 75 ms, respectively. VOT values in sentence contexts were similar, with VOTs of −51 ms for /d/, 13 ms for /t/, and 61 ms for /t̪ʰ/. Vowel onset F0 following voiceless stops /t̪ʰ/ and /t/ were higher than that following the voiced stop /d/; however, this effect was primarily observed in the isolated word context. The difference in vowel onset F0 between /t̪ʰ/ and /t/ was inconsistent across speakers, with some subjects showing higher vowel onset F0 following /t̪ʰ/ and others showing the opposite pattern. It should be noted that this study included some nonword syllables, so it remains unclear whether these patterns generalize to real word production.

Vu (Reference Vu1981) examined seven Vietnamese speakers and found that only the vowel onset F0 following /t̪ʰ/ was significantly different from that of /d/. Only two speakers showed a higher vowel onset F0 for /t̪ʰ/ than for /t/. In a study of a single female participant, Carne (Reference Carne2008) reported the highest vowel onset F0 for /t/, followed by /d/ production, with the lowest vowel onset F0 in /t̪ʰ/. All of these studies included a small number of participants and focussed exclusively on adult speakers. Further research with large samples across various age groups is needed to more comprehensively characterize VOT and vowel onset F0 in the three Vietnamese alveolar stops.

1.6. Purposes of the study

To our knowledge, no previous study has investigated the development of stop consonants in Vietnamese children using acoustic measurements. Furthermore, previous studies on VOTs and vowel onset F0 in Vietnamese adult speakers have involved small sample sizes. As a result, the nature of vowel onset F0 differences among the three Vietnamese alveolar stops remained unclear. The present study, which includes a large number of participants across different age and sex groups, aimed to examine the acoustic characteristics of stop categories in both Vietnamese children and adults. Based on previous studies in Vietnamese and other languages, the current study has three main hypotheses. First, VOTs will differ significantly among the three Vietnamese alveolar stops. Second, vowel onset F0 values will be higher following Vietnamese aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops compared to voiced stops. Finally, the absolute values and variability of both VOT and vowel onset F0 will differ between children and adults.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The current study utilized an existing dataset to investigate the phonological development in central Vietnamese children (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nguyen Phuoc, Truong Thi, Dang Thi, Ho Thi and Ha2024). The dataset includes word productions from 80 Vietnamese children, with 16 children in each age group from 3 to 7 years old. An equal number of males and females were recruited for each group. All participants had no reported history of speech, language, or hearing disorders, as confirmed by their parents and teachers. In addition, 16 healthy adult Vietnamese speakers of the Central Vietnamese dialect participated, ranging in age from 22 to 44 years, with an equal number of male and female participants. The current study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hue University of Medicine and Pharmacy. Informed consent was obtained from adult participants and from the parents of the child participants.

2.2. Data collection

Children’s speech data were collected in quiet rooms at preschools and primary schools in central Vietnam. Three words, including “thỏ” /t̪ʰɔ4/ (rabbit), “tai” /taj1/ (ear), and “đỏ” /dɔ4/ (red), were used to elicit three Vietnamese alveolar stops /t̪ʰ/, /t/, and /d/, respectively. In addition, the word “nai” /naj1/ was included as a baseline for vowel onset F0 comparison since the three target stop consonants occurred in two different tonal contexts. These stimuli were selected for the child’s familiarity and appropriateness for young children, including those as young as 3 years old. Furthermore, all of these words contained a non-high vowel, which is relevant because previous research shows that high vowels tend to produce higher F0 (Hillenbrand, Reference Hillenbrand, Getty, Clark and Wheeler1995). Participants were instructed to produce each word three times, pausing between repetitions. A three-step picture-naming task was used for children to produce target words as spontaneously as possible. First, children were asked to answer the question “What is this?” when shown an image. If they did not name the image, the researcher provided a semantic cue; for example, for the word “tai” (ear), the researcher said: “This is used to listen.” If participants still did not respond, the researcher modelled the word and asked them to imitate it. Speech recordings were made using a digital flash recorder (Marantz Model PMD670) with a built-in microphone and a sampling rate of 44 kHz. Data collection for adults’ speech took place in quiet rooms at a university using the same digital recorder. They were asked to repeat the target words three times, pausing between repetitions.

2.3. Speech transcription

Two Vietnamese researchers transcribed all speech samples using the International Phonetic Alphabet system. In cases of transcription discrepancies, the two researchers re-evaluated the items along with a third researcher, and the final transcription was determined by consensus among the three researchers. The inter-rater agreement between the two primary transcribers was 88.33%, based on 180 data items from 20 randomly selected participants (representing 20.8% of the sample).

2.4. Acoustic measurement

For the measurement of VOT and vowel onset F0 in stop consonants, only productions with the correct stop manner and place of articulation were included, in line with previous studies on voicing contrast development (Kim & Stoel-Gammon, Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009; Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980a; Zlatin & Koenigsknecht, Reference Zlatin and Koenigsknecht1976). Productions that exhibited voicing errors but were still classified as alveolar stops (e.g. /t̪ʰ/ was substituted by [t]) were included in the analysis. VOT and vowel onset F0 were measured using PRAAT software (version 6.2.21). VOT is defined as the time interval between the beginning of the release of the stop and the onset of glottal vibration. This was manually identified on the waveform and the spectrogram: the stop release was marked at the abrupt onset of acoustic energy in the spectrum, while the onset of glottal vibration was marked at the first regularly spaced vertical striation. If voicing occurred before the stop release, VOT was classified as voicing lead VOT (negative value); if voicing occurred after the release, it was classified as voicing lag VOT (positive value) (Lisker & Abramson, Reference Lisker and Abramson1964). Vowel onset F0 was measured at the onset of the vowel following the stop or nasal consonant with a 10-ms window length. This point was manually identified as the zero-crossing point of the first regular glottal period on the waveform (Ohde, Reference Ohde1984). Both VOT and vowel onset F0 values were manually extracted and recorded in an Excel file for further analysis.

To assess reliability, an independent researcher manually remeasured 11% of randomly selected tokens. A Pearson correlation coefficient was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS Version 29.0, IBM, 2022) to compare the measurements obtained by the two researchers. The correlations for both VOT and vowel onset F0 were significant, indicating strong inter-rater agreement (r(108) = .92, p < 0.001 for VOT; r(108) = .83, p < 0.001 for vowel onset F0). A correlation coefficient greater than .75 indicates a high level of agreement.

2.5. Data selection for statistical analysis

Among 96 participants, data from 20 children (four 5-year-old children, nine 4-year-old children, and seven 3-year-old children) were excluded due to articulation errors affecting either place (e.g. /t/ was substituted by [c]) or manner (e.g. /t̪ʰ/ was substituted by [s]) across all three productions of each target consonant. As a result, 912 word productions were available for VOT and vowel onset F0 measurements (76 participants * 3 repetitions *4 words). A small number of additional tokens were excluded due to background noise. The final analysis included a total of 906 tokens (224 for /t̪ʰ/, 227 for /t/ and /d/, and 228 for /n/). Consistent with previous studies, the average values for each word by each participant were used in the statistical analysis to reduce random variation and ensure that the data were representative of each subject (Lee & Iverson, Reference Lee and Iverson2011; Xu & Xu, Reference Xu and Xu2003).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS. Two separate three-way mixed analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted to examine the effect of sound category, age, and sex on VOTs or vowel onset F0. A three-way ANOVA was chosen because there are three independent variables (sound category, age, and sex). A mixed model was used since the sound category was a within-subject factor, while age and sex were between-subject factors. If a significant main effect was found, a post hoc test with Bonferroni correction was performed to assess which specific comparisons were significantly different.

3. Results

3.1. VOT of three Vietnamese alveolar stops

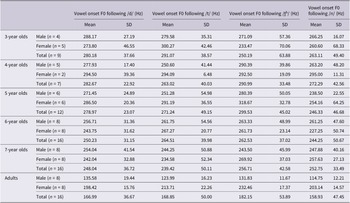

The mean and standard deviation of VOT for the three Vietnamese alveolar stops across different age groups are presented in Table 1. The phoneme /d/ was produced with voicing lead VOTs, showing negative VOT values ranging from −51.06 (SD = 11.48) in adults to −31.93 (SD = 18.49) in 3-year-old children. The phoneme /t/ was produced with short-lag VOTs, ranging from 6.29 (SD = 13.39) in 3-year-old children to 13.49 (SD = 6.13) in 6-year-old children. The phoneme /t̪ʰ/ was produced with long-lag VOTs, ranging from 48.52 (SD = 24.70) in 3-year-old children to 80.08 (SD = 35.01) in 7-year-old children.

Table 1. The voice onset time (VOT) of three Vietnamese alveolar stops

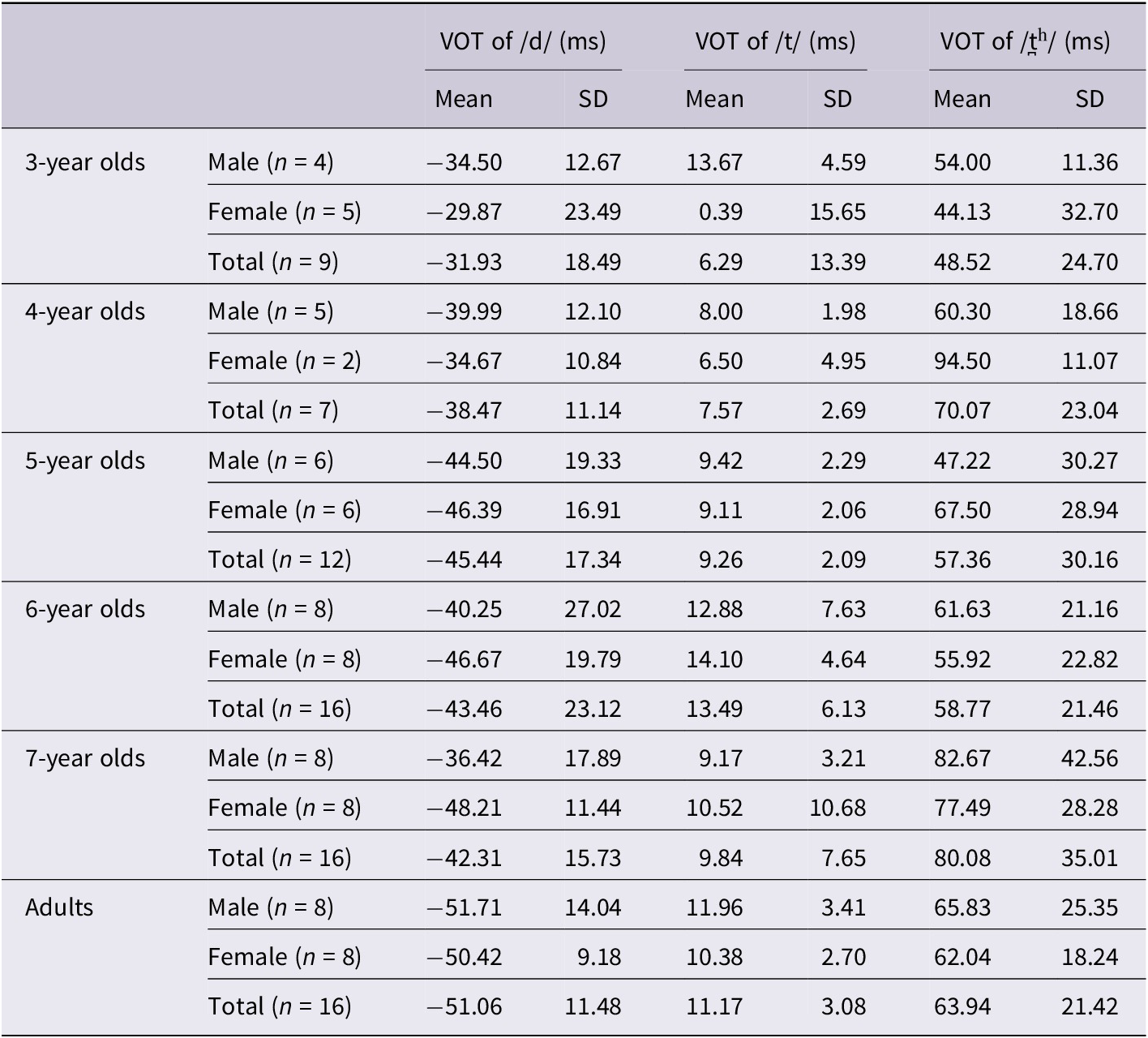

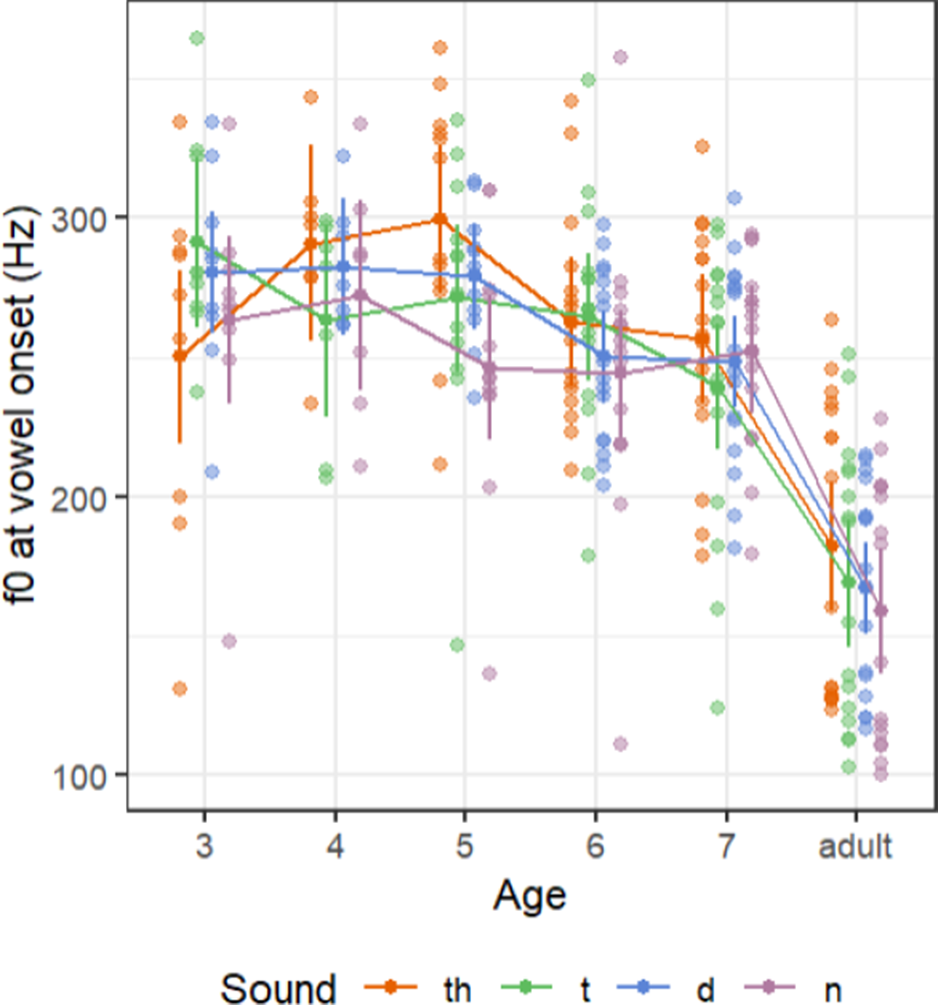

Figure 1 displays the VOT values of individual participants. The adult group demonstrated three distinct VOT ranges for three Vietnamese alveolar stops, with no participants producing overlapped VOT values across three stop categories. A fully separated VOT range for the three alveolar stops was also observed in 4-year-old children. However, some children in other age groups exhibited overlapping VOT values between the three stop categories.

Figure 1. The VOTs of three Vietnamese alveolar stops in different age groups. The estimated marginal means and standard deviations of VOTs of each sound in each age group are displayed in the foreground. The raw data of VOTs are displayed in the background.

The three-way mixed ANOVA revealed a significant two-way interaction between stop category and age (F[7.85, 100.45] = 2.35, p = .024, partial η 2 = .155) as well as a significant main effect of stop category (F[1.57, 100.45] = 538.34, p < .001, partial η 2 = .894). However, the main effects of age (F[3.93, 50.24] = 1.39, p = .241, partial η 2 = .098) and sex (F[0.79, 50.24] = 0.02, p = .893, partial η 2 = .000) were not significant.

No significant three-way interaction was found among stop category and age and sex (F[7.85, 100.45] = 0.79, p = .609, partial η 2 = .058). Similarly, the two-way interactions between stop category and sex (F[1.57, 100.45] = 0.76, p = .440, partial η 2 = .012) and between age and sex (F[3.93, 50.24] = 0.85, p = .517, partial η 2 = .063) were also not significant. Post hoc tests revealed that VOTs of three alveolar stops differed significantly from each other across all age groups (p < .001 for all comparisons). However, there were no significant differences in VOT across age groups for any of the three alveolar stops (p > .05 for all comparisons).

3.2. Vowel onset F0 following three Vietnamese alveolar stops

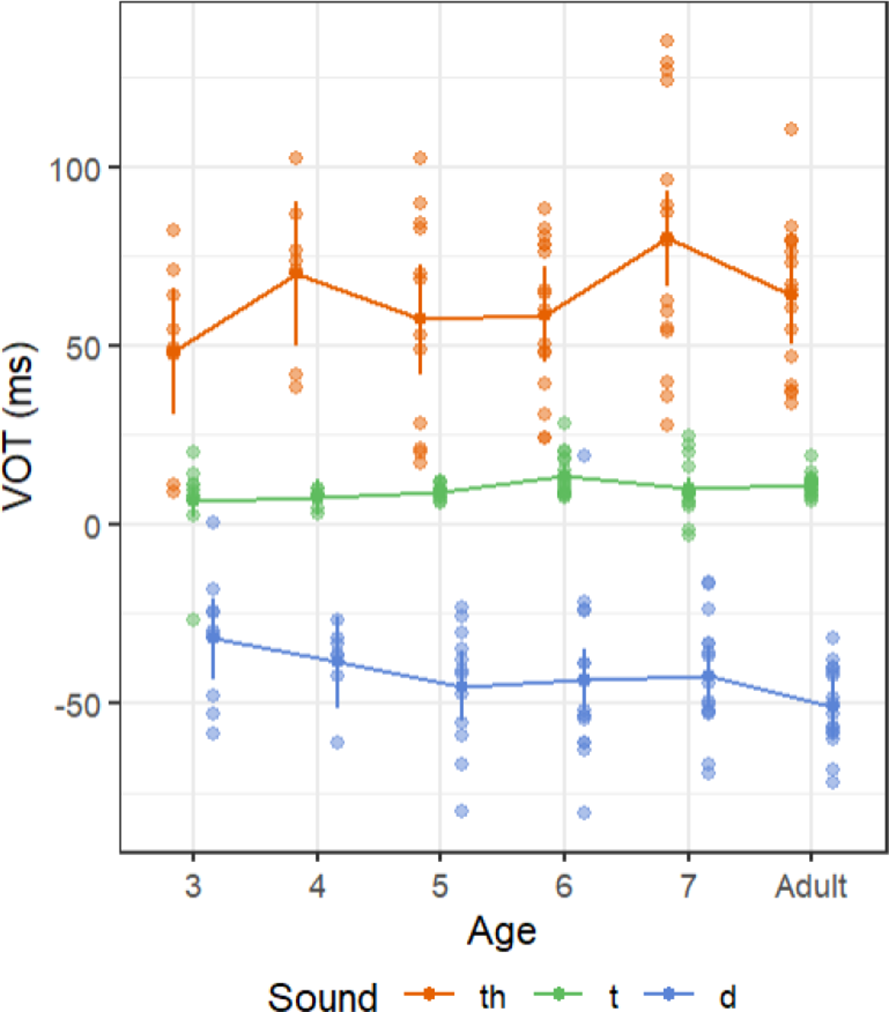

The mean and standard deviation of vowel onset F0 following the three Vietnamese alveolar stops and the nasal consonant /n/ across different age groups are presented in Table 2. For both males and females, children aged 3–7 years showed higher mean vowel onset F0 compared to adults. In male adults, the mean vowel onset F0 following a nasal consonant was lower than that of stop consonants. In female adults, the mean vowel onset F0 following a nasal consonant was lower than that following the aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops, but similar to that following the voiced stop. No systematic patterns existed in both male and female children.

Table 2. The fundamental frequency (F0) at vowel onset following four Vietnamese alveolar consonants

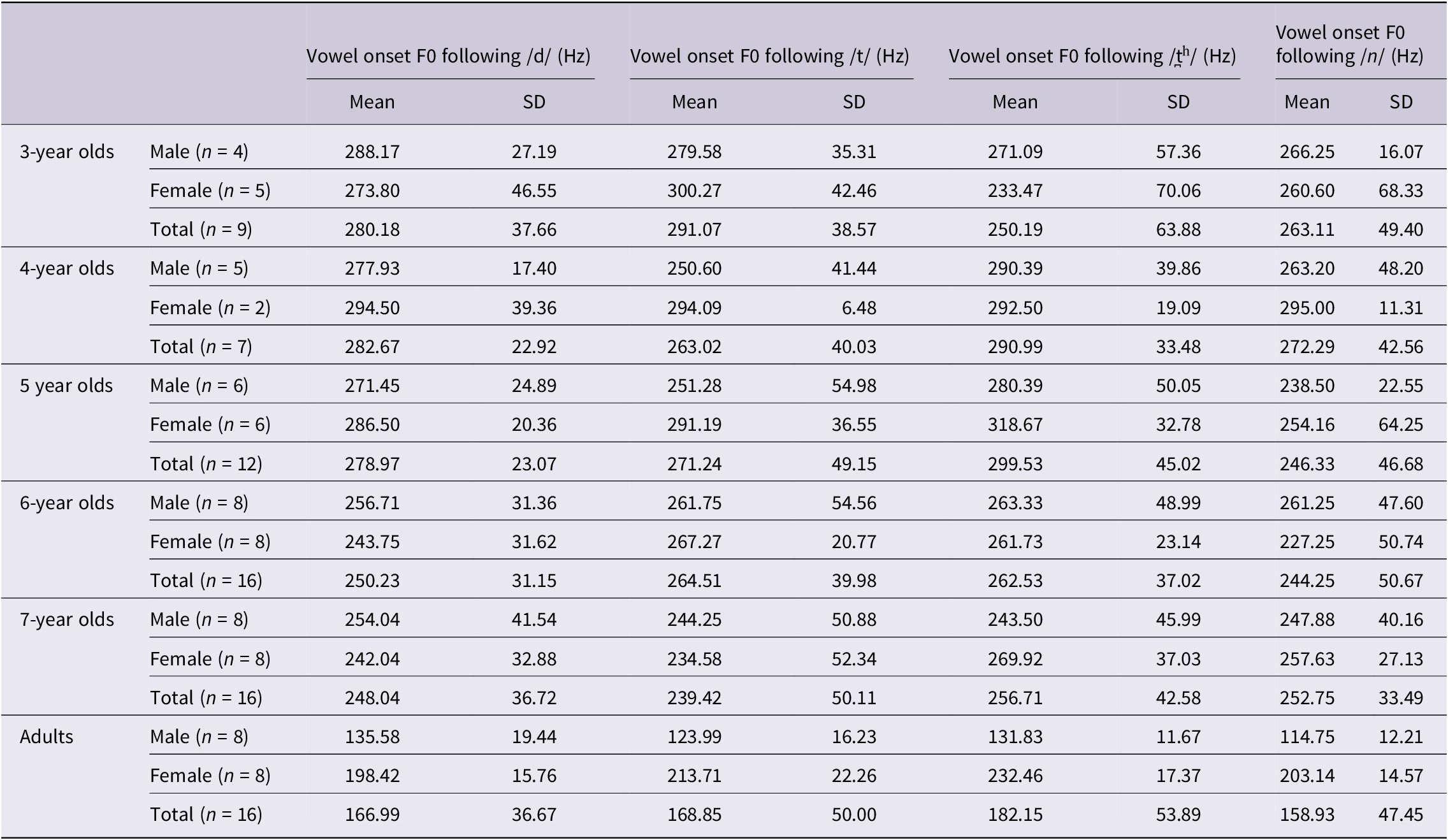

Figure 2 displays the vowel onset F0 values for the four Vietnamese consonants in individual participants. An overlap between the vowel onset F0 values of the three Vietnamese stops, and the nasal consonant was observed in all age groups. Adults produced lower vowel onset F0 compared to children. However, vowel onset F0 values were similar among age groups in children.

Figure 2. The vowel onset F0 of four Vietnamese alveolar consonants in different age groups. The estimated marginal means and standard deviations of vowel onset F0 of each sound in each age group are displayed in the foreground. The raw data of vowel onset F0 are displayed in the background.

The three-way mixed ANOVA results for the vowel onset F0 of the three stop and nasal consonants revealed significant two-way interaction effect between sound category and age (F[13.56, 173.54] = 2.35, p = .006, partial η 2 = .155) and between age and sex (F[5, 64] = 5.36, p < .001, partial η 2 = .295). Other interaction effects were not significant (p > .05). Significant main effects were also found for sound category (F[2.72, 173.54] = 4.23, p = .008, partial η 2 = .062), age (F[5, 64] = 26.34, p < .001, partial η 2 = .673), and sex (F[1, 64] = 7.18, p = .009, partial η 2 = .101).

For the age-by-sex interaction, post hoc tests showed that the female adults had significantly higher vowel onset F0 than male adults. However, no significant differences were found between boys and girls among children. Children’s vowel onset F0 was significantly higher than that of male and female adults (p < .05 for 3- and 4-year-olds, p < .001 for other comparisons). Within the female group, two comparisons were not significant: between female adults with 6-year-olds (p = .199) and between female adults and 7-year-olds (p = .166). Regarding the sound category-by-age interaction, no significant difference in vowel onset F0 between the three sound categories was found in any age groups (p > .05), except for the 5-year-old group. In this group, vowel onset F0 following /t̪ʰ/ and /d/ were significantly higher than that following /n/ (p < .001 for /t̪ʰ/ and p < .05 for /d/).

3.3. Developmental change in voicing contrast production in Vietnamese children

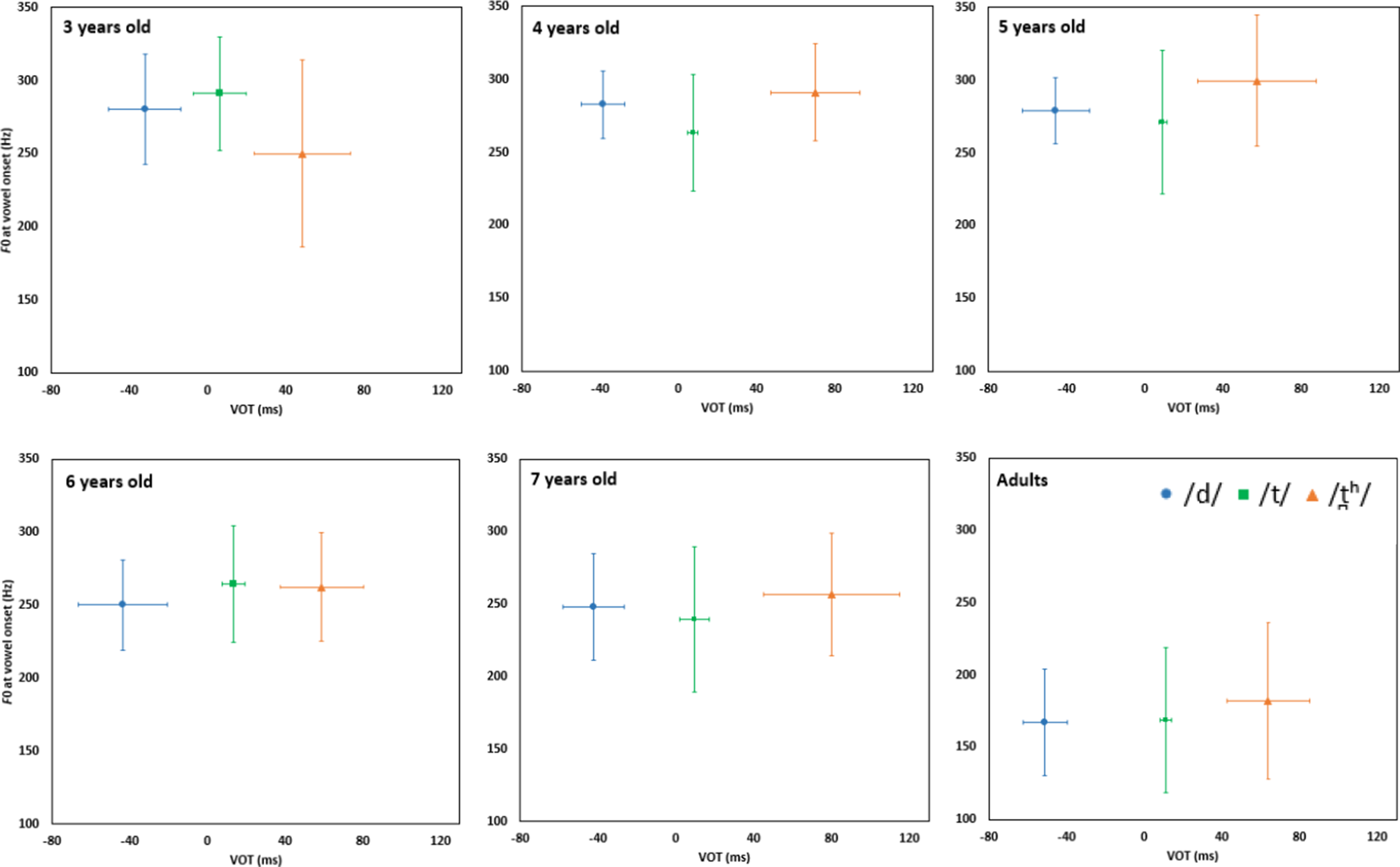

Figure 3 presents the means and standard deviations of VOT and vowel onset F0 for Vietnamese children and adults. VOT values are displayed on the x-axis and the vowel onset F0 values on the y-axis. The figure clearly demonstrates that the three consonants /t̪ʰ/, /t/, and /d/ are primarily distinguished by their VOT. Qualitative observation indicates that the voicing contrast in 3-year-old Vietnamese children differs notably from that of other age groups. Specifically, the mean VOT for the aspirated voiceless stop /t̪ʰ/ in 3-year-old children was lower than in other age groups, and their productions of the voiced stop /d/ showed shorter negative VOT values compared to other age groups. Additionally, the standard deviation for the unaspirated voiceless stop /t/ was higher in 3-year-old children than in the older groups. As a result, the VOT ranges across the three voicing categories were less distinct in 3-year-old children than in older children and adults. Clear separation of VOT ranges among the three Vietnamese alveolar stops began to emerge at age four.

Figure 3. The means and standard deviations of VOT and vowel onset F0 of three Vietnamese alveolar stops in different age groups.

In addition to differences in mean values, Figure 3 also shows greater VOT variability in children than in adults. Specifically, the standard deviations of VOT for the three alveolar stops were higher in 3-year-old, 6-year-old, and 7-year-old children than in adults. Furthermore, the standard deviations of /d/ and /t̪ʰ/ in 5-year-old children and of /t̪ʰ/in 4-year-old children were also greater than those observed in adults.

4. Discussion

4.1. VOT of three Vietnamese alveolar stops

The current study found that the voiced stop /d/ was produced with voicing lead, the voiceless unaspirated stop /t/ with the short-lag VOT, and the voiceless aspirated stop /t̪ʰ/ with the long-lag VOT. These findings were consistent with previous studies in Vietnamese and other languages with a similar three-way voicing contrast (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Whalen and Docherty2019; Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986; Kirby, Reference Kirby2018). While prior research in Vietnamese has primarily focussed on the Northern dialect (Kirby, Reference Kirby2018), the current study confirms that adult speakers of the Central dialect exhibit similar VOT patterns. In comparison to Thai, which also features a three-way contrast, Vietnamese adults demonstrated comparable VOT values for /t/, but produced /t̪ʰ/ with shorter VOTs and /d/ with less negative VOTs than Thai adults (Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986; Kirby, Reference Kirby2018).

In children, the findings of the current study show that Vietnamese children begin developing the voicing contrast among alveolar stops by or before the age of three. Significant VOT differences among the three alveolar stops were observed across all child age groups. This finding aligns with findings from English-speaking children, where the distinction between the voiced and voiceless stops emerged early, before the age of three (Kewley-Port & Preston, Reference Kewley-Port and Preston1974; Lowenstein & Nittrouer, Reference Lowenstein and Nittrouer2008; Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980a; Snow, Reference Snow1997; Tyler & Saxman, Reference Tyler and Saxman1991; Zlatin & Koenigsknecht, Reference Zlatin and Koenigsknecht1976). However, the developmental timeline observed in the current study differed from the findings of Thai-speaking children (Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986) and Spanish-speaking children (Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980b). Thai-speaking children did not fully acquire all voicing contrasts until the age of five (Gandour et al., Reference Gandour, Petty, Dardarananda, Dechongkit and Mukngoen1986). Similarly, some Spanish-speaking children aged 3–4 years did not fully distinguish between voiced and unaspirated voiceless stops (Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980b). However, Eilers et al. (Reference Eilers, Oller and Benito-Garcia1984) reported that four out of seven Spanish-speaking children aged two years showed clear voicing distinctions. Due to the small sample size in many of these studies, direct comparisons between languages based on their results may be challenging.

Although VOT values of the three alveolar stops were significantly different across all age groups, individual data revealed some overlap in VOT ranges between the three stop categories in children. Specifically, overlaps between /t̪ʰ/ and /t/ were observed in the three age groups (3, 5, and 6 years), whereas /t/ and /d/ were clearly distinguished in children aged 4 years and older (see Figure 1). In the current study, the overlap between /t̪ʰ/ and /t/ was largely attributed to children producing /t̪ʰ/ as [t], consistent with previous perceptual studies on Vietnamese speech acquisition (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Nguyen Phuoc, Truong Thi, Dang Thi, Ho Thi and Ha2024; Phạm & McLeod, Reference Phạm and McLeod2019). These studies reported the earlier age of acquisition of /t/ and /d/ (around 4 years old) compared to the voiceless aspirated /t̪ʰ/, which was acquired between ages 5;6 and 6. This pattern aligns with findings from English-speaking children, where long-lag VOT stops are generally more difficult to produce than short-lag VOT stops (Kewley-Port & Preston, Reference Kewley-Port and Preston1974; Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980a). According to these authors, young infants tend to produce short-lag VOTs in the early stages of voicing contrast development, as long-lag VOTs require more precise timing control between supralaryngeal and laryngeal activities and more complex muscular activity in vocal folds adduction (Kewley-Port & Preston, Reference Kewley-Port and Preston1974). Since the youngest participants in the current study were 3 years old, earlier developmental stages reported in infant studies (Hitchcock & Koenig, Reference Hitchcock and Koenig2013; Macken & Barton, Reference Macken and Barton1980a) could not be captured. Further studies, including younger children, may help to identify the onset of voicing contrast development and the early stage of the acquisition process in Vietnamese children.

4.2. Vowel onset F0 following three Vietnamese alveolar stops

While VOT plays a vital role in distinguishing voicing categories in Vietnamese, the role of vowel onset F0 still remains underexplored. Previous studies have reported higher vowel onset F0 following voiceless aspirated stops compared to voiced stops (Kirby, Reference Kirby2018; Vu, Reference Vu1981), but the distinction in vowel onset F0 between aspirated and unaspirated voiceless stops in Vietnamese remained inconsistent (Carne, Reference Carne2008; Kirby, Reference Kirby2018; Vu, Reference Vu1981).

The present study found no significant differences in vowel onset F0 across the four phoneme contexts, with only a few exceptions (e.g. 5-year olds). Specifically, when the voiceless aspirated /t̪ʰ/ and the voiced stop /d/ were produced with the same tone and vowel (e.g. /t̪ʰɔ4/ and /dɔ4/), their vowel onset F0 was statistically insignificant. Similarly, no significant differences were observed between the unaspirated voiceless stop /t/ (as in /tɑj1/) and the nasal /n/ (as in /naj1/), which also shared the same vowel and tone. These findings were different from those of Kirby (Reference Kirby2018), who reported that vowel onset F0 in /d/ and /n/ contexts was lower than in /t̪ʰ/ and /t/ contexts. This discrepancy may be attributable to dialectal variation. While Kirby’s study focussed on speakers of the Northern Vietnamese dialect, the current study examined speakers of the Central dialect. Although further studies may need to confirm these findings, the results of the current study suggest that consonant voicing may have a minimal impact on vowel onset F0 in Central Vietnamese.

One possible explanation for the lack of F0 distinction between /t̪ʰ/ and /d/ is the implosive nature of Vietnamese voiced stop consonants (Kirby, Reference Kirby2011; Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2003). Nagano-Madsen and Thornell (Reference Nagano-Madsen and Thornell2012) found that implosives tend to rise F0 throughout the following vowels, in contrast to plosive stops. Thus, this acoustic characteristic may explain the similar vowel onset F0 between /t̪ʰ/ and /d/ observed in this study. However, the dialectal effects of implosive stop production on vowel onset F0 still need further investigation. In other words, while research suggests that implosive stops are more clearly and consistently produced in the Northern dialect (Phạm, Reference Pham2003; Brunelle, Reference Brunelle2009), higher vowel onset F0 for /d/ than /t̪ʰ/ was not observed in studies of Northern dialect speakers (Kirby, Reference Kirby2011). The implosive nature of Vietnamese /d/ and its influence on vowel onset F0 in Vietnamese dialects remain open questions for future research.

Although comparing vowel onset F0 between /t̪ʰɔ4/ and /tɑj1/ is complicated by their tonal difference, it could still be hypothesized that /t̪ʰɔ4/ would yield a lower onset F0 than /tɑj1/, based on findings from Xu and Xu (Reference Xu and Xu2003). Given that both Mandarin Chinese and Vietnamese are tonal languages, some cross-linguistic parallels may be drawn. While several studies have reported higher vowel onset F0 following aspirated stops than unaspirated stops (Han & Weitzman, Reference Han and Weitzman1970; Hanson, Reference Hanson2009; Jeel, Reference Jeel1975; Kim & Stoel-Gammon, Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009), Xu and Xu (Reference Xu and Xu2003) found the opposite in Mandarin Chinese: across all four tones, aspirated stops led to lower onset F0 values than unaspirated stops. Notably, the largest F0 difference between the two stops was seen in the low tone (falling rising), while the high tone (steady high) showed minimal difference.

Although the tonal systems of Vietnamese and Mandarin differ, Vietnamese tone 4 (e.g. /t̪ʰɔ4/) may be comparable to Mandarin’s low tone, and Vietnamese tone 1 (e.g. /tɑj1/) to Mandarin’s high tone. Based on these parallels, one might expect /t̪ʰɔ4/ to have a lower vowel onset F0, whereas /tɑj1/ to have a higher vowel onset F0. However, the present study found no significant differences in vowel onset F0 between aspirated and unaspirated stops across all groups, with a few exceptions (e.g. 5-year olds). This suggests that vowel onset F0 may not play a substantial role in distinguishing stop consonants in Vietnamese – at least in the Central dialect – where the three-way alveolar stop contrast can be robustly signalled by VOT alone. As noted earlier, Vietnamese children were found to acquire this three-way stop contrast by the age of three. In contrast, Thai- and Korean-speaking children –whose languages also exhibit a three-way stops contrast – tend to rely on both VOT and vowel onset F0 for voicing distinction. The relatively minimal role of vowel onset F0 in Vietnamese may thus facilitate the earlier acquisition of stop contrast in Vietnamese-speaking children compared to their peers acquiring Thai or Korean.

Additionally, potential influences from vowel differences cannot be ruled out, as the target stimuli involved the vowels /ɔ/ and /a/. Yet both are non-high vowels, which typically yield lower F0s compared to high vowels (Hillenbrand et al., Reference Hillenbrand, Getty, Clark and Wheeler1995). Still, the effects of vowel quality and tonal differences on vowel onset F0 in the present stimuli warrant further investigation.

4.3. Development of speech production in Vietnamese children

The development of speech production in Vietnamese children is highlighted by two key findings in the current study: first, the progression of voicing contrast, and second, the reduction in variability of acoustic parameters. Regarding voicing contrast, although statistical analysis found a significant difference in VOT between the three alveolar stops across all age groups, individual data showed considerable overlap in the VOT values among children. In contrast, adult speakers demonstrated clearly distinct VOT ranges for each voicing category. Notably, the VOT ranges of the three voicing categories were less distinct in 3-year-old children compared to older children and adults. These findings suggest that young children have not yet fully mastered the adult-like laryngeal and supralaryngeal gestures for producing different voicing categories.

In terms of acoustic variability, the current study found greater variability in both VOT and vowel onset F0 in children compared to adults. This developmental change has also been reported in previous studies (Kent, Reference Kent1976; Kent & Forner, Reference Kent and Forner1980; Kim & Stoel-Gammon, Reference Kim and Stoel-Gammon2009; Koenig, Reference Koenig2000; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Potamianos and Narayanan1999; Ohde, Reference Ohde1985; Whiteside & Hodgson, Reference Whiteside and Hodgson2000; Whiteside et al., Reference Whiteside, Dobbin and Henry2003; Yu et al., Reference Yu, De Nil and Pang2015). These findings indicate that children continue to refine their speech production skills as they develop, and this refinement continues even after the perceptual acquisition phase. Prior research suggests that adult-like stability in speech production is typically achieved around puberty (Kent & Forner, Reference Kent and Forner1980; Yu et al., Reference Yu, De Nil and Pang2015).

4.4. Difference in VOT and vowel onset F0 between the two sexes

The current study found no significant difference in VOT between male and female participants. This aligns with previous literature, where findings on sex differences in VOT have been inconsistent. While some studies have reported longer VOTs in female speakers (Ryalls et al., Reference Ryalls, Zipprer and Baldauff1997; Swartz, Reference Swartz1992; Whiteside & Marshall, Reference Whiteside and Marshall2001), others have found either the opposite pattern or no significant difference (Koenig, Reference Koenig2000; Morris et al., Reference Morris, McCrea and Herring2008; Oh, Reference Oh2019; Sweeting & Baken, Reference Sweeting and Baken1982; Whiteside & Irving, Reference Whiteside and Irving1998; Yu et al., Reference Yu, De Nil and Pang2015). In terms of the vowel onset F0, sex-related differences were observed only in adult speakers. This finding is consistent with previous research showing that F0 differences between males and females are generally not significant in children (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Potamianos and Narayanan1999; Whiteside & Hodgson, Reference Whiteside and Hodgson2000). According to Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Potamianos and Narayanan1999), a clear sex difference in F0 emerges around age 13, when males begin to exhibit a more pronounced decrease in F0 compared to females. This drop in F0 for male speakers is likely due to anatomical changes during puberty, including increases in vocal fold mass and the differentiation of its layered structure (Harries et al., Reference Harries, Hawkins, Hacking and Hughes1998).

5. Limitations and future studies

The current study found that VOT plays a crucial role in distinguishing three Vietnamese alveolar stop categories. Vietnamese children were shown to develop voicing contrasts between these stops by the age of three or earlier. Despite important findings, the study has several limitations. First, it relied on an existing database, in which only one word per consonant was used to elicit stop consonants. In addition, the tonal and vowel contexts of the target consonants were not fully controlled, limiting the ability to isolate their effects on vowel onset F0. Future studies should employ stimuli with consistent phonetic contexts to more precisely examine the role of vowel onset F0. Finally, the current study only included children aged three and older. To fully understand the developmental trajectory of voicing contrast acquisition in Vietnamese, further studies should investigate earlier stages of development, including infancy.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Fulbright Scholarship awarded to the second author. The authors thank Professor Nhan C. Ha, Ngan Q. Truong Thi, and Hang T. Dang Thi for their contribution to the data collection and transcription. The authors also appreciate Dr. Jeremy Donai at Texas Tech University Health Science Center and Dr. Ferenc Bunta at the University of Houston for their valuable feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Disclosure of use of AI tools

Google Scholar was used to search for journal articles relevant to the current study.