“Archive” is now a big umbrella. Once carrying the narrow meaning of an authorized repository of physical documents, it has expanded to encompass just about any analogue or digital collection of original source material, whether manuscripts, printed text, images, or audio files.Footnote 1 This wider definition is not without controversy, but few would now dispute applying “archive” to digital materials collected around a topic, rather than privileging institutional and documentary provenance, as some archivists insist.Footnote 2 Like a traditional archive, digital databases store information, but they also go further in allowing a wider range of users to easily access, reorder, and compare substantial amounts of information. In other words, a database both collects and connects information. Databases are used differently by social scientists, many of whom work with big data, and humanists, who tend to dig deeper and reach less widely.Footnote 3 This brief article introduces a historical database that bridges the gap between the distinct challenges of these two perspectives: the Medieval Londoners Database (MLD).

MLD is a prosopographical database—that is, a database that enables what some would call “collective biography.” It includes multiple references to an array of activities (such as election to an office or participation in a property transaction) that the database then links to specific individuals.Footnote 4 Prosopography has, of course, been critical to the expansion of social history in the last half-century, as it enables the study of ordinary people who are sparsely documented as individuals but whose aggregated commonalities (for example, in terms of occupation, political office, wealth, neighborhood, social networks) are well-sourced. The advent of database computing in the mid-twentieth century was critical here, since it allowed researchers to produce biographical information about hundreds or thousands of individuals and quickly answer queries about them or their social groups. When online or digital prosopographies emerged in the early twenty-first century, the field changed more radically, first by requiring large (and costly) interdisciplinary teams of scholars and IT professionals, and second by creating public-facing resources that were fully accessible and without size limits.Footnote 5 These databases have their challenges, but as the example of MLD demonstrates, they also have enormous potential.

MLD is a pandemic baby, launched in June 2020 after two years of preparatory work. The database itself comprises the major part of the Medieval Londoners website, where users can also access a curated guide to the primary written sources and other online resources for the study of medieval London (Figure 1). It includes a pedagogy section with relevant syllabi and digital projects,Footnote 6 and hosts three sub-sites: a MLD Blog, a section on the Visual Sources of Medieval London, and a crowd-sourcing project about property owners and lessors in one London neighborhood.Footnote 7 These various sections reflect the main goal of the project, which is “to provide students and scholars with a standardized dataset that could support prosopographical studies of the people of medieval London.”Footnote 8 Prosopographical studies always set thematic, geographical, and chronological parameters, which for this project are defined as the activities of residents of the city of London and its suburbs of Southwark and Westminster between ca. 1100 and 1520. The end date is flexible, since London officeholders and testators are recorded up to ca. 1540.

Figure 1. Menu items in the Resources section of the Medieval Londoners project, https://medievallondoners.ace.fordham.edu/resources/.

The over 34,000 digital records currently in MLD (with thousands more added each year) match criteria recognized by the American Society of Archivists: “a selection of digital records or digital surrogates of records made available as a curated online collection.”Footnote 9 Each MLD record details an “activity” that reflects a past event (such as entry to a guild, appearance as a litigant, registration of a will, payment of a tax, or any kind of officeholding) as documented in a specific primary source, whether in manuscript, print, online, or embedded as a reference in a secondary source. In so doing, MLD follows the factoid prosopographical model in which each separate point of information is not considered a statement of fact, but an asserted “factoid,” in order to highlight the interpretation required to extract the information from a source and structure it into the standardized wordings and categories (called ontologies) that a computer can read.Footnote 10 The majority of these sources are digitized print publications of primary sources (in translation if available), but others are secondary sources with multiple assertions that can be backed up by a primary source that is also cited in the MLD record. In other words, MLD itself is a born-digital archive, but relies heavily on analogue collections for its content.

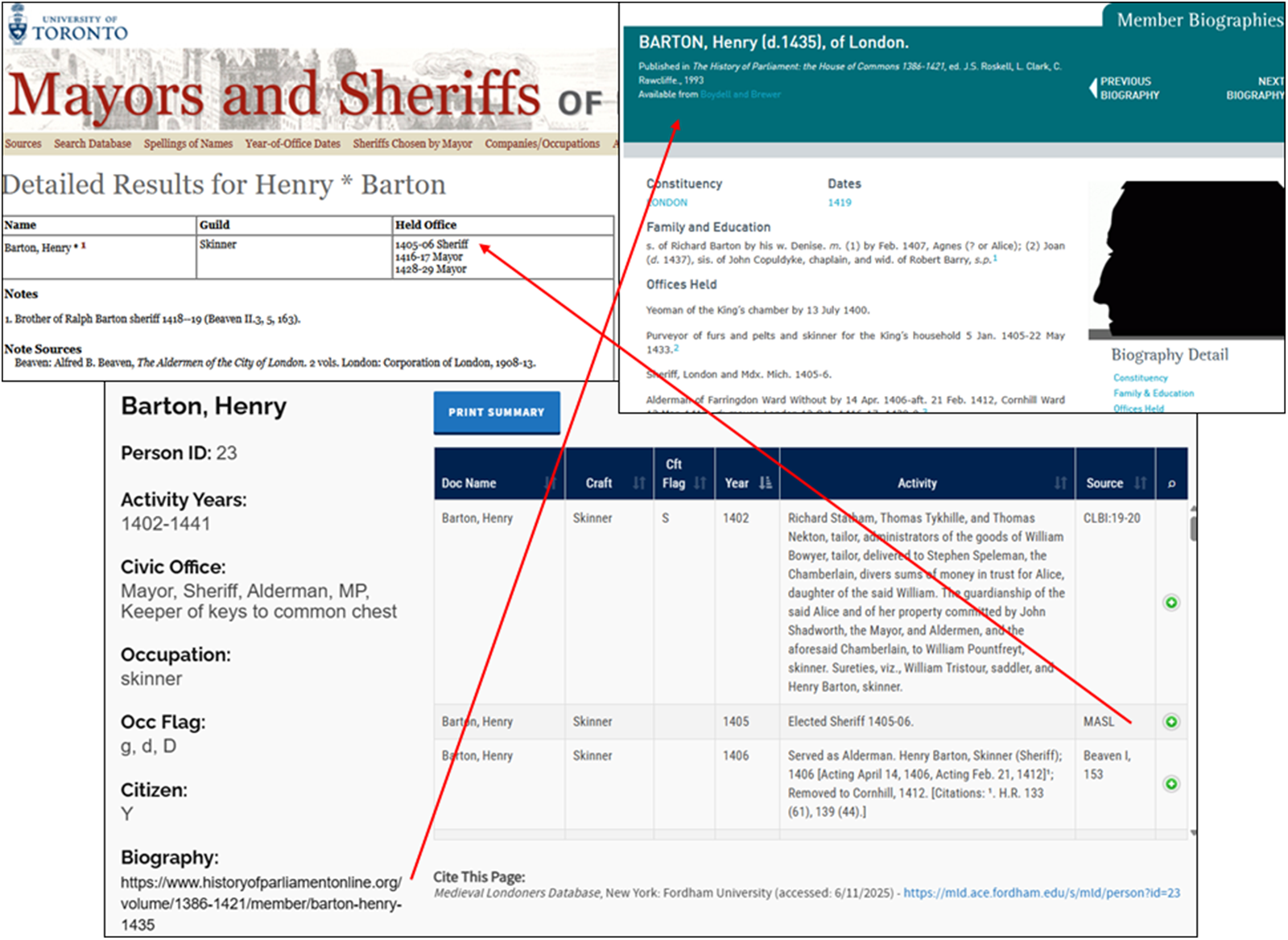

The born-digital nature of MLD is especially evident in its ability to link its records to data elsewhere on the web. This function is one of the reasons that OmekaS was chosen as the MLD digital platform. The S stands for “semantic,” which means that we can tag MLD data fields so that they can link to relevant information on other websites, such as the biographies of MPs in the History of Parliament Online (Figure 2) or the tenement locations of property transactions on the mapping platform, Layers of London.Footnote 11 Such linking is made easier because each individual in MLD has a unique URI (Uniform Research Identifier: highlighted in blue under Cite this Page at the bottom of Figure 2). Specific MLD records can also be linked to their original source texts on other digital platforms such as British History Online.Footnote 12 The power, flexibility, and range of the semantic web represent the future of prosopographies and online archival collections alike.

Figure 2. The semantic web functions of MLD are evident in two of eighteen records in Henry Barton's profile summary; these records provide direct links to Barton's entries in the online History of Parliament (https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1386-1421/member/barton-henry-1435) and the M\mayors and Sheriffs of London site (https://masl.library.utoronto.ca/search?name=henry+barton&yearhttps://masl.library.utoronto.ca/search?name=henry+barton%26year).

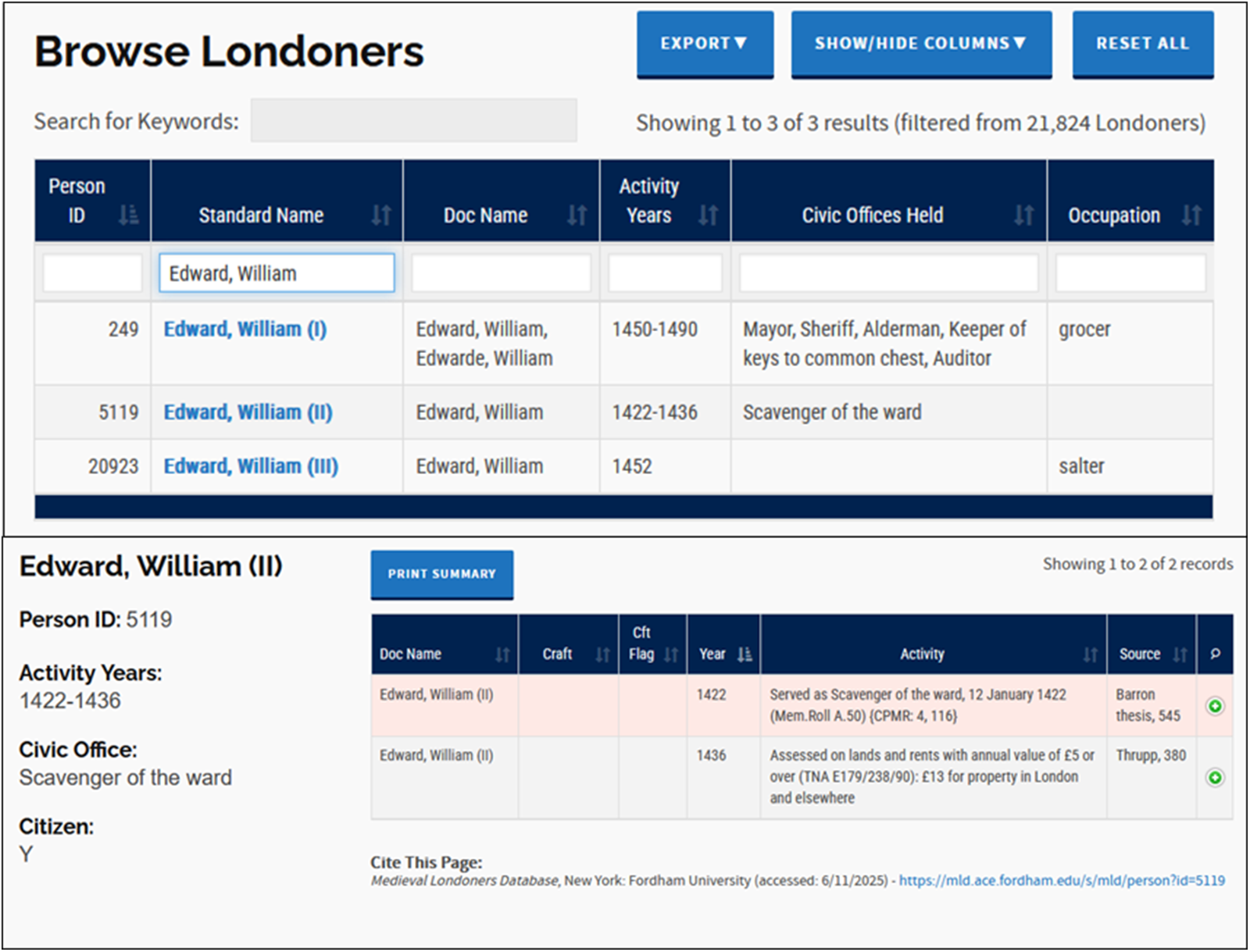

As a prosopographical database, MLD has functions that go beyond those of a traditional archival collection. Three are especially important. One is the name linkage (also called “disambiguation”) that MLD provides in connecting a multitude of records to one individual, each identified by a unique Person_ID.Footnote 13 Discerning which factoids about an individual named William Edward belong with which of the three William Edwards already in MLD (or not) requires skilled analysis by trained editors (see Figure 3). Name linkage represents the chief analytic function of any prosopographic database because it not only facilitates further research by scholars but also enlarges the range of users to family historians and the general public.

Figure 3. The top image shows three individuals named William Edward, each identified by a unique Person_ID. The bottom image is the profile summary for one William Edward (PID 5119). One of his records is colored pink to indicate that the name linkage for this record is tentative.

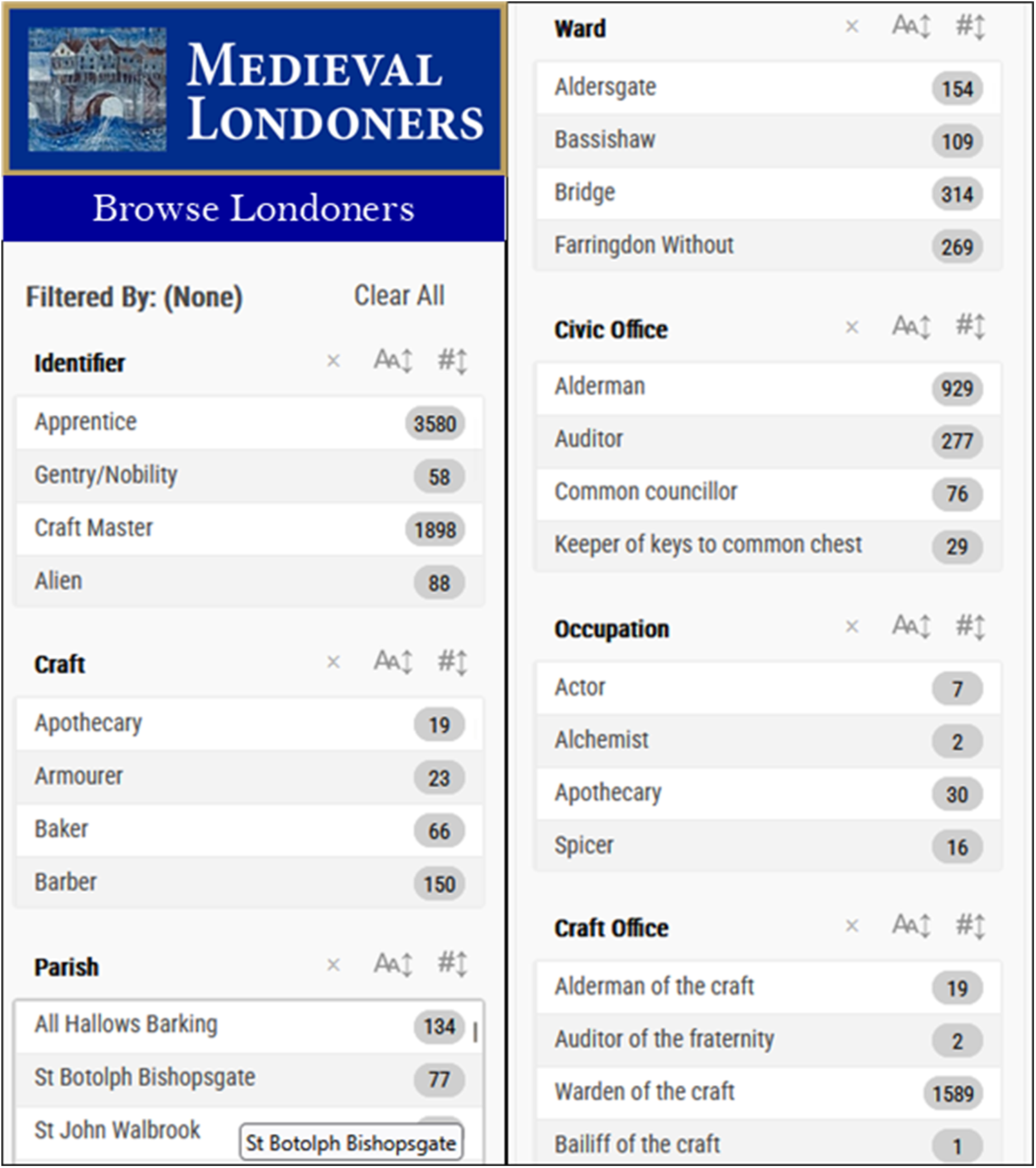

Figure 4. The menu of filtering options in the Browse Londoners search option, which searches on individual Londoners, not individual records (for which there is a Browse Records function with different filters). The figures across from each option indicate the total number of individuals who fit this category; thus there are 3,574 individuals identified as an apprentice in MLD (as of 1 June 2025).

A second function helps to make transparent the editorial intervention involved in recording specific characteristics (such as an individual's occupation or the date of an event) by using codes in a “flag” field associated with these characteristics in the database entry.Footnote 14 So when MLD catalogers handle an occupational name (such as John the Smith) from before the year 1300, they follow the standard practice of medievalists in assuming that this person pursued that occupation, but make their assumption clear by adding a N code to the flag field attached to the Occupation field.

The third analytic tool of MLD represents the most significant advantage of a database format: the ability to allow users to search for a wide range of data, such as: 1) a specific name, occupation, guild, craft office, political office, ward, parish, or ecclesiastical affiliation; 2) a particular identity, such as apprentice, citizen, clergy, foreigner, gentry/nobility, guild master, Jew, orphan, widow, or woman; and 3) a specific type of activity, such as those who made a will or were named as an heir or executor; were elected or served in a civic or craft office; were involved in a property transaction as an owner or lessor; were associated with the maritime sector, commercial property, or a dower; or designated their burial location.Footnote 15

MLD's search and filtering functions can also be combined so that, for example, it can show the 63 records dealing with Jewish women before 1290 or compare the geographical distribution by ward and parish of the 133 Mercers, 102 Drapers, and 88 Grocers elected to the Court of Aldermen.

Because MLD has no source limitations and adds thousands of records each year, it reminds users of its changing coverage by providing a regularly updated list of what is included in MLD, as well as a detailed list of each source and how it has been mined for data.Footnote 16 These reminders indicate, for example, that MLD coverage of the major offices (mayor, sheriff, alderman, MP, coroner) is complete, but minor offices (such as ward constable or aleconner) are not. Just about all members of crafts such as Mercers and Fletchers are included (thanks to the generous contribution of data by scholars who have researched these crafts for years),Footnote 17 and many embroiderers, grocers, pinners, skinners, and tailors are in MLD because cataloguers have concentrated on extant sources for these groups, but occupations like the ironmongers or dyers are much less thoroughly covered. The good news is that a volunteer cataloguer can turn this situation around in months by concentrating on sources for one of these crafts.

The database functions and analytic tools provided by MLD make it a kind of super-powered and ever-growing archival collection. Like a traditional archive, MLD provides copious information but still requires researchers to do much of the analytic work, not least because the “factoids” for one person can sometimes contain conflicting information. Yet it goes beyond archival functions in culling data from a wide variety of sources, some of it linked data brought in from other websites, and in structuring data so that it can be searched by almost any field.

The features of MLD that take it beyond mere archival storage represent its most exciting possibilities, especially in terms of linking individual factoids to specific individuals and structuring the data to make it searchable in multiple ways. Analytic tools such as the built-in filters enable many types of analysis, but users can go further by downloading, manipulating, and even adding to MLD's data. These and other functions allow for deep dives into medieval social, economic, legal, and gender history. MLD provides sufficient data, for example, to address how the taxable wealth and political status of certain occupational groups compared in the late thirteenth and early fifteenth centuries, or whether widows of the craft elites were more likely to remarry someone in the same craft as their first husband, questions that previously could only be answered with months of research using print and archival sources. In so doing, MLD emulates and expands beyond the functions of more familiar document-based archives.

Maryanne Kowaleski is the Joseph Fitzpatrick S. J. Distinguished Professor Emerita of History and Medieval Studies at Fordham University. The creation and success of MLD, like any digital database project, relies on the collaborative work of many people, particularly Katherina Fostano, M.L.I.S. Thanks also goes to the contributing editors and cataloguers (“The Project Team,” Medieval Londoners, https://medievallondoners.ace.fordham.edu/about/about-us/) and members of Fordham IT, especially Andrew Angelopolous, Alan Cafferkey, Fleur Eshghi, Heather V. Hill, and Upendar Thaduri. I also thank Judith M. Bennett and Cynthia Herrup for their comments on a draft of this article. Please address any correspondence to: kowaleski@fordham.edu