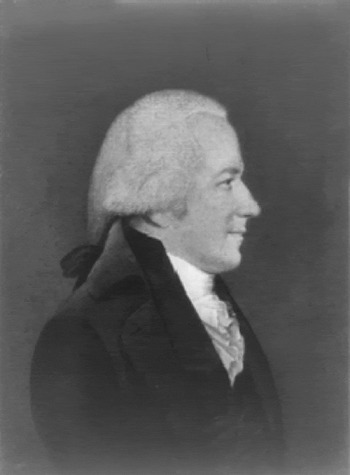

Figure 1. This portrait is based upon the painting by James Sharpless when Hamilton was thirty-seven (or thirty-nine) years old. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

HAMILTON's CONTROVERSIAL REPUTATION

The truth is that I am an unlucky honest man, that speaks my sentiments to all and with emphasis.

Alexander Hamilton, 1780We may know more than we want to know about the sexual practices of contemporary politicians and celebrities, but the eminent dead keep their secrets. Biographers, queer theorists, and historians of sexuality probe the past for evidence of illicit attachments or forbidden propensities that might illuminate a particular life or era. John F. Kennedy's prolific sexual adventures were not revealed until after his death. Abraham Lincoln's sexuality is under scrutiny and debate. Emily Dickinson's affections have become the subject of much scholarly speculation, and Walt Whitman was outed after decades in the closet. In their sexual affiliations and other characteristics, famous writers and thinkers inspire different, often competing, forms of identification and are claimed by various constituencies.

As an outsider with a mysterious childhood, Alexander Hamilton is, as psychologists say, a good “hook” for a projective identification. In 2004, the 200th anniversary of the duel, the New York Times Magazine published an article about Hamilton entitled “Nobody's Founder,” but since then Hamilton's reputation has been on the upsurge, and he has been claimed by a number of interest groups: in particular, gay men (because of his close friendship with a fellow officer), African Americans (because of rumors about his origins), and fundamentalist Christians (because he took communion on his deathbed). For his admirers Hamilton is a source of political capital. His ideas and proposals about the debt, protectionism, and an American manufacturing base are in the news in the early twenty-first century. Quotations from his writings, particularly The Federalist Papers, are wielded as weapons by both conservatives and progressives.

Although the Old Left saw Hamilton as an elitist, possibly a monarchist, and a promoter of industrial capitalism – Howard Zinn inaccurately calls Hamilton a “merchant” in his People's History of the United States – contemporary American progressives like Daniel Lazare of The Nation and Thom Hartmann have called attention to his explicit support for habeas corpus (in The Federalist # 84), his efforts on behalf of an American manufacturing base, and his surprisingly enlightened attitudes about race and slavery.Footnote 1 Candidate Barack Obama mentioned Hamilton in his March 2008 Cooper Union speech as Lincoln had before him; on that occasion, Lincoln called Hamilton one of “the [three] most-noted anti-slavery men of those times.”Footnote 2

As one of the founders of a new republic, Hamilton knew he would be in the history books, but his image, representations of his physical presence, and speculation about his private life circulate on the Internet in ways that would surely astonish him. There have been recent allusions to him in politically savvy television programs, particularly The Daily Show, The Colbert Report, Law and Order, and 30 Rock. Lin-Manuel Miranda is producing a concept hip-hop album about him and has already performed “The Hamilton Mixtape” in the White House for President Obama. It is posted on YouTube.Footnote 3 In an interview, Miranda said of Hamilton, “he was so gangsta, I can't even begin to describe it.”Footnote 4 Alexander Hamilton not only has admirers in the fields of politics and history; he also has fans.

Hamilton was the youngest, best-looking, most controversial, and arguably the most brilliant of the major founders. He was almost fifty years younger than Benjamin Franklin, twenty-three years younger than Washington (rumored to be his father), twenty years younger than Adams, fourteen years younger than Jefferson, and four years younger than Madison. At the time of his death in the famous duel, Hamilton was the age Barack Obama was in 2009. Aaron Burr lived another thirty-two years after the duel, dying at the age of eighty. Adams and Jefferson outlived Hamilton by twenty-two years, with Adams surviving to ninety-one and Jefferson to eighty-three. Madison died in 1836 at the age of eighty-five. As Ron Chernow has observed, Hamilton's premature demise gave his political opponents a chance to shape, and to distort, his reputation and legacy.

Hamilton's life story is as improbable and seductive as his financial work – assumption of the debt, sinking funds, protectionism, taxation, a national bank – is dry and daunting. Hamilton was a Romantic avant la lettre. He fought with both the pen and the sword. He led a dramatic life before Byron supplied the model for literary characters like Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Lermontov's Pechorin (Pushkin and Lermontov were killed in duels). Born on a Caribbean island far from any center of power, Hamilton fought on the battlefields of a revolution, rose to the peak of national power and international fame, was ensnared in the first sex scandal in American politics, fell from power because of a tragic flaw in his temperament (an excess of candor, his friends said), and died a violent, premature death. He made lifelong, devoted friends and bitter, ruthless enemies. His story is the stuff of tragedy.

The suitability of Hamilton's life story for the screen was obvious to early Hollywood. Three silent films were made about him. The first such film, concerning his notorious extramarital affair, was entitled The Beautiful Mrs. Reynolds (1918) and starred Carlyle Blackwell (aged thirty-four – about right) as Hamilton. The Library of Congress lists the film as lost. Another 1918 film, My Own United States, stars Duncan McRae as Hamilton; the casting of actors for the parts of Burr, Pendleton, Van Ness, and General Wilkinson suggests that the film portrays the fatal duel and Burr's subsequent treasonous adventures. Unless it is in a private collection, it too is lost. In 1924 and 1931 two films were made with the title Alexander Hamilton, one starring Allen Connor and the other George Arliss.

Hamilton has also appeared on television, particularly since 2004, when the duel was reenacted at Weehawken, Ron Chernow's biography appeared to critical acclaim, and the New-York Historical Society staged its exhibition Alexander Hamilton: The Man Who Made Modern America. In the spring of 2008 Hamilton was the subject of a PBS “American Experience” program, in which he was played rather lugubriously by Brian O'Byrne, an actor then starring in the Lincoln Center production of Tom Stoppard's Coast of Utopia. In 2009 Rufus Sewell played Hamilton in HBO's miniseries John Adams. Here he was presented as negatively as Adams could have wished, but with neither the substance nor the fireworks of the two men's disagreements. A new PBS special on Hamilton will air in the spring of 2010.

Hamilton's admirers like him for many reasons, major and minor, and most of these reasons are unknown to his detractors. “He was evidently very attractive,” wrote Henry Cabot Lodge in his 1882 biography, “and must have possessed a great charm of manners, address, and conversation.”Footnote 5 He was fearless, even reckless, narrowly escaping death on the battlefields of the American Revolution. He was equally bold in expressing his ideas and beliefs and seemed to take pleasure in opposing dominant discourses, beginning his political life as a revolutionary pamphleteer and orator. One night he saved his college president from a mob intent on tarring and feathering the Tory. He was fluent in French, having learned it in childhood, and he sometimes acted as Washington's translator during the war.Footnote 6 Hamilton's financial acumen might suggest that he was only interested in economics, but he was as broad-minded, intellectually curious, and well read as other prominent Founders. He loved music and literature. His first publications were poems, and he wrote serious verse and satirical doggerel intermittently throughout his life. One friend regarded his poetry as “strong evidence of the elasticity of his genius.”Footnote 7 Even Aaron Burr “frequently characterized” Hamilton as “a man of strong and fertile imagination, of rhetorical and even poetical genius.”Footnote 8 When Hamilton and Gouverneur Morris crossed swords in the courtroom, one witness reported, they “equally resorted for illustration to Shakespeare, Milton, and Pope.”Footnote 9

A wide range of emotions is apparent in Hamilton's personal correspondence, from playful wit to suicidal despair. “I have no other wish than to make a brilliant exit as soon as possible,” he confessed in 1781. “'Tis a weakness; but I fear I am not fit for this terrestreal [sic] Country.”Footnote 10 His grandson, the psychologist Allan McLane Hamilton, believed that “he undoubtedly possessed that form of nervous instability common to many active public men and characterized by varying moods, which was sometimes expressed by alternating depression on the one hand and gayety [sic] on the other.”Footnote 11 In The Hypomanic Edge (2005), Johns Hopkins Medical School psychologist John D. Garnter diagnosed Hamilton (and certain other prominent American immigrants) with “hypomania,” a milder form of manic-depression whose symptoms include high levels of energy, creative productivity, and risk-taking.Footnote 12 As Chernow and Atherton observed, Hamilton displayed some of the eccentricities of genius, talking to himself in public when he was preoccupied with a project and writing his portion of the Federalist Papers at breakneck speed. He was so brilliant that listeners (including John Marshall) expressed their astonishment at his intellect, so charismatic that Congress would not allow him to make an important policy presentation in person, so youthful and handsome that other men seem either jealous of, or attracted to, him.

Hamilton was a firebrand – John Adams complained of his “effervescence” – but the common characterization of him as arrogant and domineering does not do him justice.Footnote 13 Off the political battlefield he was, his friends testify, cheerful, charming, and witty. A particularly close and longtime friend, Robert Troup (1757–1832), remembered that “his heart was noble, generous, kind, and free from hypocrisy, envy, and jealousy.” Another friend, Judge James Kent (1763–1834), praised Hamilton's personal qualities in the strongest terms: “He was blessed with a very amiable, generous, tender, and charitable disposition, and he had the most artless simplicity of any man I ever knew. It was impossible not to love as well as respect and admire him.”Footnote 14

Two long-standing rumors have severely damaged Hamilton's reputation. Despite refutations by Stephen Knott and Ron Chernow, both continue to circulate in the press and on the Internet. One of these is Henry Adams's anecdote that at the dinner table, Hamilton once referred to “the people” as “a great beast.” In Alexander Hamilton and the Persistence of Myth, Stephen Knott argued this was a libel. “It was his [Adams's] zeal to demonstrate Hamilton's alleged hostility to the common man,” writes Knott, “that led Adams to engage in an act of academic dishonesty that has reverberated through scholarly circles to this day.”Footnote 15 Henry's great-grandfather John had felt a particularly personal animus against Hamilton and uttered a number of virulent slurs. In maligning Hamilton, Henry carried on a family tradition and struck a successful propaganda blow. The “great beast” anecdote even appears in modernist poetry: Ezra Pound's Cantos and William Carlos Williams's Paterson.

The other damaging rumor is that Hamilton was a monarchist. Jefferson and his allies regularly denounced him as such. Gouverneur Morris (1752–1816), the friend who delivered Hamilton's eulogy, recorded that belief in his diary. By doing so, Judge James Kent indignantly objected, “Gouverneur Morris did him great injustice.”Footnote 16 “All his actions and all his writings as a public man,” Kent declared, “show that he was the uniform, ardent, and inflexible friend of justice and of national civil liberty.”Footnote 17 Robert Troup was also adamant on the subject:

The General has been charged by his Enemies with being friendly to the design of introducing a Monarchy into the United States. This charge is wholly without foundation. On this subject Mr. Troup, from his long and close intimacy with the General, is confident he knew his very soul.Footnote 18

Why would Hamilton, the illegitimate second son of the penniless fourth son of a member of the Scottish nobility, support a system that depends upon legitimacy and primogeniture? In Empire of Liberty, Gordon Wood acknowledges that Hamilton was “in many respects a natural republican,” but a few pages later seems to give credence to Morris's charge of monarchism.Footnote 19 “Hamilton was to exhaust himself,” Chernow observes, “in efforts to refute lies that grew up around him like choking vines. No matter how hard he tried to hack away at these myths, they continued to sprout deadly new shoots.”Footnote 20

Hamilton's contemporaries admired his manners and his appearance. His good friend and fellow Federalist Fisher Ames (1758–1808) rhapsodized about him, particularly admiring his eyes (“of a deep azure, eminently beautiful”) and his physical deportment (“one of the most elegant of mortals” with “easy, graceful, and polished movements”).Footnote 21 A male contemporary wrote of Hamilton, “His complexion was exceedingly fair and varying from this only by the almost feminine rosiness of his cheeks. His might be considered, as to figure and color, an uncommonly handsome face.”Footnote 22

Historians and novelists have echoed such descriptions. In the opening chapter of Founding Brothers, “The Duel,” Joseph Ellis vividly imagines Hamilton and his nemesis Aaron Burr as opposites in both coloring and temperament:

Burr had the dark and severe coloring of his Edwards ancestry, with black hair receding from the forehead and dark brown, almost black, eyes … Hamilton had a light peaches and cream complexion with violet-blue eyes and auburn-red hair, all of which came together to suggest an animated beam of light to Burr's somewhat stationary shadow. Whereas Burr's overall demeanor seemed subdued, as if the compressed energies of New England Puritanism were coiled up inside him, waiting for the opportunity to explode, Hamilton conveyed kinetic energy incessantly expressing itself in bursts of conspicuous brilliance.Footnote 23

In a History Channel special, Gore Vidal also remarked upon the contrast in the two men's coloring, comparing them to checkers on a game board.Footnote 24 In his novel Burr, Vidal has Aaron Burr describe his future victim through a gay lens: “As a youth, Hamilton was physically most attractive, with red-gold hair and bright blue eyes and a small but strong body.”Footnote 25 In her 1902 novel The Conqueror, Gertrude Atherton imagines a teenaged Hamilton on the verge of delivering his maiden revolutionary speech in lower Manhattan:

They [the crowd] stared at Hamilton in amazement, for his slender little figure and curling fair hair, tied loosely with a ribbon, made him look a mere boy, while his proud, high-bred face, the fine green broadcloth of his fashionably cut garments … gave him far more the appearance of a court favorite than a champion of liberty. Some smiled, others grunted, but all remained to listen, for the attempt was novel, and he was beautiful to look upon.Footnote 26

HAMILTON AND BURR AS GALLANTS

Both were short and handsome, witty and debonair, and fatally attractive to women.

Ron ChernowIn his own day, Hamilton had a reputation as a “gallant,” or ladies' man. He said as much in a flirtatious 1777 letter to Kitty Livingston, writing, “you know, I am renowned for gallantry.”Footnote 27 In The Conqueror, Gertrude Atherton wrote of Hamilton, “He is vaguely accused of being the Lothario of his time, irresistible and indefatigable.”Footnote 28 When he was in the army, Hamilton's fellow officers teased him about the many young women with whom he had brief romantic relationships. Even after his marriage and before the Mrs. Reynolds scandal, he was the subject of rumor and innuendo. Abigail Adams wrote to John, “Oh, I have read his heart in his wicked eyes. The very devil is in them. They are lasciviousness itself.”Footnote 29 Her husband coarsely described Hamilton as having “a superabundance of secretions which he could not find whores enough to draw off.”Footnote 30 Given their puritanical tenor (Adams was also shocked by Ben Franklin's relationships with women), both could be read as backhanded compliments.

Among the many colorful episodes in Hamilton's life was the first sex scandal of the new republic. While working as treasury secretary in Philadelphia, Hamilton, then in his mid-thirties, a husband and the father of four, was visited by a young and attractive Mrs. Maria Reynolds, who presented herself as a damsel in distress and sought his financial assistance. It was July of 1791, and Hamilton's family had gone north to escape the humid Philadelphia summer. Hamilton visited Mrs. Reynolds at her lodgings that night and was drawn into a sexual relationship that lasted over a year. When her husband James appeared on the scene, Hamilton paid hush money to him under the guise of loans. Setting a precedent that future American politicians would scrupulously avoid, Hamilton confessed at length, in detail, and in writing, sacrificing his private reputation to defend his public integrity.

To some biographers, the Reynolds affair was a kind of return of the repressed, with Hamilton reenacting the role of his father. A massive 1976 biography by Robert Hendrickson propounds a more compelling theory – that the Reynolds affair was the result of a collusion among Jefferson, Madison, and Aaron Burr to entrap Hamilton and ruin his political career. The origin of this theory is a disturbing 1791 letter from Robert Troup in which he warned Hamilton of a budding conspiracy: “There was every appearance of a passionate courtship between the Chancellor [Robert R. Livingston], Burr, Jefferson & Madison when the latter two were in town. Delenda est Carthago [Carthage must be destroyed] I suppose is the Maxim adopted with respect to you.”Footnote 31 Shortly thereafter, Mrs. Reynolds made her appearance. Later Burr served as Mrs. Reynolds's divorce attorney. She subsequently married another of the conspirators. If Hendrickson's conspiracy theory is correct, these events would have fueled the particular animus Hamilton felt for Burr.

The former Nixon speechwriter and Sunday Times columnist William Safire gives a quite different and more negative account of the Reynolds affair in his 2000 novel Scandalmonger. The title refers to James Callender, who was one of Jefferson's henchmen in his newspaper wars against Hamilton and who later, after a breach with Jefferson, revealed the relationship with Sally Hemings. Following the lead of a Jefferson biographer, Safire represents Hamilton as on the take as treasury secretary. Safire's novel might be read in part as evidence of Republican animosity to Hamilton, the Founder most associated with taxes and “big government,” but I quote it here because of its author's evident interest in the sexual proclivities of its characters. Safire imagines Burr coldly watching himself in a mirror as he copulates with Mrs. Reynolds; by contrast, Safire's Hamilton is ardent: “The lovemaking was worthy of his passion; she inspired him to heights and depths he had never reached before in a life of no mean experience with women.”Footnote 32 In fact, Mrs. Reynolds may not have been Hamilton's only paramour. Hamilton's contemporaries and some of his biographers believed that he had a long adulterous relationship with his glamorous and sophisticated sister-in-law, Angelica Schuyler Church, a married woman also admired by Thomas Jefferson. “The dashing Hamilton had become a local [Manhattan] celebrity,” writes Willard Stearne Randall in his 2003 biography, “Angelica his constant elegant companion.”Footnote 33 Once again, flowery, suggestive letters are the primary evidence, although Randall has also done interesting research into Hamilton's expenditures on Angelica. The differences in biographers' conjectures can be comical. John C. Miller is confident that although she desired him, “Hamilton felt no overmastering passion for Angelica Church,”Footnote 34 while Hendrickson muses, “For Hamilton there would probably never be any sweeter flesh than Angelica's.”Footnote 35 Randall is quite certain the affair took place, providing close readings of the correspondence, while Chernow believes that the Schuyler family would never have been so fond of Hamilton had he behaved in such a scandalous manner.

The long eighteenth century was an era of renegotiated gender roles and dangerous liaisons. Brothels flourished, upper-class women in Europe openly conducted adulterous affairs, and there were “molly houses” in London.Footnote 36 The Earl of Chesterfield's letters to his son “on the Fine Art of becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman” dispensed advice to the literate public; Aaron Burr was one of the book's admirers. Like Hamilton, Burr was a gallant; in fact, Hamilton described Burr as a “voluptuary in the extreme.”Footnote 37 Burr's memoirist, admirer, and younger friend, Matthew L. Davis, was so horrified by the many letters Burr had kept as trophies that he burned them after the old roué's death. Explaining his decision, Davis wrote in part,

Major Burr, while yet at college, had acquired a reputation for gallantry. On this point he was excessively vain, and regardless of all those ties which ought to control an honourable mind. In his intercourse with females he was an unprincipled flatterer, ever prepared to take advantage of their weakness, their credulity, or their confidence. She that confided in him was lost. In referring to this subject, no terms of condemnation would be too strong to apply to Colonel Burr.Footnote 38

Burr's sexual politics, as Davis describes them, could be read as confirming Hamilton's suspicions about his political will to power. George Haggerty observes of the rake and poet Lord Rochester, “libertine love seems to be more about power than it is about desire.”Footnote 39 Haggerty quotes Harold Weber, who believes that aristocratic libertinism “flaunts a provocative self-fashioning that depends on a conventional misogynist understanding of hierarchical relations between the sexes.”Footnote 40

Historians have speculated about how the political context and personal rivalry made the duel (although not Hamilton's death) inevitable. “Longtime political opponents almost expected duels,” observes Joanne Freeman in Affairs of Honor, “for there was no way that constant opposition to a man's political career could leave his personal identity unaffected.”Footnote 41 Joseph Ellis writes, “It is difficult for us to fully fathom the threat that Burr represented to Hamilton because we know that the American experiment with republican government was destined to succeed.” In his fears about Burr, Hamilton was not alone. George Washington never liked Burr and expressed doubts about his integrity. After Burr's imperial escapades in the western territories, Jefferson energetically prosecuted Burr for treason. According to Matthew Davis, “Mr. Jefferson's malignity towards Colonel Burr never ceased until his last breath.”Footnote 42

Plutarch's Lives was one of Hamilton's favorite books; he seemed to regard the history of Rome as a cautionary tale for the new American republic. The “embryo-Caesar” (as he called him) that Hamilton feared the most was Colonel Burr.Footnote 43 Although Vidal's novel represents its eponymous hero as a small-d democrat, Burr had shape-shifted opportunistically between political parties. In a 4 January 1801 letter to John Rutledge, Hamilton expressed his “extreme anxiety” about the possibility of Burr's becoming President of the United States. One paragraph reads,

By natural disposition the haughtiest of mortals, he [Burr] is at the same time the most creeping to answer his purposes. Cold and collected by nature and habit, he never loses sight of his object and scruples no means of accomplishing it. He is artful and intriguing to an inconceivable degree. In short all his conduct indicates that he has in view nothing less than the establishment of the Supreme Power in his own person.Footnote 44

In order to explain the duel, Gore Vidal's novel Burr has Hamilton crudely accuse Burr of an incestuous relationship with his daughter Theodosia, but since Hamilton excoriated Burr in the above fashion, there is no need to imagine more personal slurs.

TOO PRETTY TO BE STRAIGHT? HAMILTON AS GAY ICON

Although he was only about five foot seven in height and slight in build, he had a commanding air, and men and women alike were readily attracted to him.

Gordon WoodDespite Mrs. Reynolds, the salacious rumors about Angelica Church, his numerous progeny, and the Lothario reputation, the Internet carries on another conversation about Hamilton's sexuality – in this case, his supposed homosexuality. Hamilton appears on gay websites and is included in a book of famous gay Americans.Footnote 45 He even has a military veterans' association in San Francisco named after him, much as Lincoln has the Log Cabin Republicans. The two conversations never cross paths: Hamilton the womanizer is absent from accounts of Hamilton the gay soldier and vice versa.

In Burr, Gore Vidal insinuates that Hamilton exploited his good looks to win the patronage of older, more eminent men. The novelist is particularly cynical about Hamilton and Washington's relationship, seeing it as “unrequited passion” on the older man's part, opportunism and concealed contempt on the younger's.Footnote 46

Hamilton and Washington's relationship was not as unusual as Burr implies. Madison and Jefferson were also close political allies and probably closer friends. In his biography of Franklin, Gordon Wood writes, “most of the mobility in the eighteenth century was sponsored mobility.”Footnote 47 It was a form of noblesse oblige for aristocrats like Lord Rockingham to recognize and assist gifted younger men like Edward Burke. In the colonies, not only Hamilton but also Ben Franklin, no beauty, received help from older mentors.

The cause of the gay rumor is twofold: Hamilton's long relationship with the childless Washington and, much more persuasively, the affectionate letters young Hamilton wrote to his fellow officer John Laurens (1754–1782) during the Revolution. In her novel Atherton writes that Laurens “took Hamilton by storm” and describes their friendship as “romantic and chivalrous.”Footnote 48

Laurens was the son of the president of the Continental Congress, Henry Laurens, a wealthy South Carolina planter. Like Hamilton, Laurens had heterosexual credentials; in London he impregnated a young woman and then married her to preserve her reputation. In April of 1779 Hamilton began a letter to Laurens as follows: “Cold in my professions, warm in my friendships, I wish, my Dear Laurens, it might be in my power, by action rather than words, to convince you that I love you.”Footnote 49 The above sentence is the closest thing to a “smoking gun” in the correspondence of the two young men. It contains the word “friendships,” yet it is a declaration of love. The phrase “by action rather than words” is particularly suggestive of what George Haggerty calls “transgressive desire.” In his book Men in Love, Haggerty argues that the word love serves a particular function in Western culture “precisely because of the way it euphemizes desire (lust), and a heteronormative culture has always been able to use it to short-circuit, as it were, questions of sexuality and same-sex desire.”Footnote 50

In a self-mocking move typical of his youthful correspondence, Hamilton pretends to blame Laurens for his own feelings: “you should not have taken advantage of my sensibility to steal into my affections without my consent” (emphasis added). Sensibility was, of course, a keyword of educated eighteenth-century society; gentlemen were expected to exhibit it in their behavior and correspondence. In Sensibility and the American Revolution, Sarah Knott devotes scholarly attention to young Colonel Hamilton's epistolary demonstrations of “sensibility,” examining not the Laurens letters but the long, emotional accounts (some of which were published in newspapers) that Hamilton wrote after the discovery of Benedict Arnold's treason.Footnote 51 As an illegitimate outsider among men born to privilege, it must have been particularly important to Hamilton that he manifest all the traits of a gentleman.

Hamilton's April 1779 letter proceeds playfully to forgive Laurens for violating Hamilton's emotional autonomy, adopts a dispassionate tone to discuss military matters, and tactfully alludes to Laurens's wife and child in England. After exhausting those topics, Hamilton writes, “And Now my Dear as we are on the subject of a wife, I command and empower you to get me in Carolina.”Footnote 52 The content of this sentence seems calculated to allay any suspicion of transgressive desire. In fact, it could be interpreted as a striking instance of a homosocial discourse interrupting a homoerotic one, for Hamilton then launches into a long, lighthearted description of the qualities he desires in a wife (“I lay most stress upon a good shape”). In the following year he would become engaged to Elizabeth Schuyler and write her a number of love letters with heartfelt passages like the following:

I stopped to read over my letter; it is a motley mixture of fond extravagance and sprightly dullness; the truth is I am too much in love to be either reasonable or witty; I feel in the extreme; and when I attempt to speak of my feelings I rave … Love is a sort of insanity.Footnote 53

It is worth noting what Hamilton's letters to Laurens do not contain. There are none of the physical allusions – no references to Laurens's hair, eyes, or body – that a lover typically makes about the beloved. There is no language as sexually loaded as Billy Green's praise of Abraham Lincoln's physique: “his thighs were as perfect as a human being could be.”Footnote 54 There is, however, suggestive language, even after the engagement. Reproaching Laurens for not writing often enough, Hamilton writes, “like a jealous lover, when I thought you had slighted my caresses, my affection was alarmed and my vanity piqued.”Footnote 55 In another letter Hamilton writes Laurens, “your impatience to have me married is misplaced; a strange cure, by the way, as if after matrimony I was to be less devoted than I am now.”Footnote 56

Some of Laurens's letters to Hamilton survive. On 14 July 1779, Laurens began a letter, “Ternant will recount to you how many violent struggles I have had between duty and inclination – how much my heart was with you, while I appeared to be most actively employed here.”Footnote 57 The rest of the letter concerns military matters, and the “you” may refer collectively to Washington's “family,” not to Hamilton alone: “Clinton's movement, and your march in consequence, made me wish to be with you.”Footnote 58 A letter dated 18 December 1779 is affectionately but casually signed, “My Love, as usual. Adieu.”Footnote 59

Hamilton's biographers differ in their assessments of the relationship. In The Intimate Life of Alexander Hamilton (1910), Allan McLane Hamilton quotes from one of Hamilton's letters to Laurens, and says of those three musketeers, Hamilton, Laurens, and Lafayette, “there was a note of romance in their friendship, quite unusual even in those days.”Footnote 60 Miller's Portrait in Paradox takes a different stance: “Hamilton and Laurens belonged to a generation of military men that prided itself not upon the hard-boiled avoidance of sentiment but upon the cultivation of the finer feelings. Theirs was a language of the heart, noble, exalted, and sentimental.”Footnote 61 In his 1999 biography, Richard Brookhiser points out that all the young officers of Washington's staff, not just Hamilton and Laurens, wrote affectionately to one another: “Modern readers unfamiliar with this background [the sentimental literature of the eighteenth century] who come across the effusions of Washington's staff, can misread them as evidence of erotic ties.”Footnote 62 In The Intimate Lives of the Founding Fathers, Thomas Fleming mentions Laurens only in passing, focusing instead on Hamilton's feelings for his wife and sister-in-law.Footnote 63

However, every Hamilton biography seems to necessitate a new interpretation of, or at least a new angle on, its subject. Breaking from Miller's contextual explanation of the Laurens letters, James Thomas Flexner, author of the strangely negative biography The Young Hamilton begins the chapter “A Romantic Friendship” with this dramatic sentence: “As the military frustrations of 1779 had loomed so foreseeably ahead, Hamilton had found himself overwhelmed by passionate emotions for his fellow aide, Lieutenant Colonel John Laurens.”Footnote 64 Flexner does not become more explicit than this. Randall's 2003 biography implicitly dismisses Flexner's reading, referring to Laurens as Hamilton's “best friend” and observing that “the two exchanged, sometimes, very personal letters.”Footnote 65 Chernow's remarkably judicious 2004 biography devotes serious attention to the relationship, considers the possibilities, and concludes that Hamilton had an “adolescent crush” on his friend.Footnote 66

Among historians and biographers there is no consensus. To some the letters are merely a fashionable discourse of sensibility among young men who imagined themselves to be Roman soldiers risking their lives to found a new Republic, gentlemen who lived in an era when emotional susceptibility was valorized over stoic machismo. To others, Hamilton's are love letters that reveal a gay infatuation. To a few, the whole business is irrelevant; what matters is the political work, not the amorous life. But against such thinkers Eve Sedgwick argued in Between Men that “what counts as the sexual … is itself political.”Footnote 67 Hamilton's era, the mid-eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth, was, Sedgwick wrote, a period of “condensed, self-reflective, and widely influential change in economic, ideological, and gender arrangements.”Footnote 68 She elaborated,

I will be arguing that the concomitant changes in the structure of the continuum of male “homosocial desire” were tightly, often causally bound up with other more visible changes; that the emerging pattern of male friendship, mentorship, entitlement, rivalry, and hetereo- and homosociality was in an intimate and shifting relation to class; and that no element of that pattern can be understood outside of its relation to women and the gender system as a whole.Footnote 69

The homosocial dimension of Hamilton's biography is obvious. Laurens, Lafayette, Edward Stevens, Robert Troup, James Kent, and Gouverneur Morris (another Lothario) were among Hamilton's close friends; the Reverend Knox of St. Croix, the merchant Nicholas Cruger, General Nathanael Greene, and George Washington were among his mentors; Jefferson, Adams, and Burr were his rivals and enemies. Unlike Burr, the grandson of Jonathan Edwards, Hamilton was a self-made man and a foreigner. “I am a stranger in this country,” he wrote unhappily to Laurens in 1780, “I have no property here, no connexions.”Footnote 70 Friends and mentors were therefore all the more important to him.

In my view, the ultimate homosocial episode in Hamilton's personal history was neither his friendship with Laurens nor his professional and personal relationship with Washington, but his duel with Aaron Burr. Instead of the affectionate consummation of a long-standing desire, it was the violent consummation of a prolonged rivalry between two politicians similar in age, size, military background, sexual attractiveness, and vaulting ambition. If I am correct, the spectrum of homosociality would include not one, as Sedgwick postulated, but two forbidden zones: not only the sexual desire of men for other men but also the homicidal desire of men to eliminate male rivals rather than cooperate or compete with them. If Hamilton's relationship with Laurens verged on the former, his association with Burr verged on the latter. The duel took place at a dangerous intersection between eighteenth-century homosociality and an older, more ruthless and aristocratic code of behavior.

What is at stake in speculations about the sexuality of historical figures? Of C.A. Tripp's book The Intimate Life of Abraham Lincoln (2004), playwright and gay activist Larry Kramer asserted, “It will change history. It's a revolutionary book because the most important president in the history of the United States was gay. Now maybe they'll leave us alone, all those people in the party he founded.”Footnote 71 Kramer's expectations seem unduly optimistic for a number of reasons. First, the Republican Party of today bears little resemblance to the party of Lincoln. Second, people do not relinquish their beliefs and prejudices easily: unlike James Buchanan, a “confirmed bachelor” with a close male friend, Lincoln was married and had four children, so there will always be those who dispute Tripp's claims. Third, the making of individual exceptions is a long-standing tactic of all prejudices, whether racist, anti-Semitic, or homophobic.

Larry Kramer has been working on a book called The American People in which he lays claim not only to Lincoln but also to other famous Americans. Although it is four thousand pages long and still unpublished, and although Kramer has no scholarly credentials, it is already getting exposure in the press. Following Vidal's lead, Kramer has recently been claiming that Hamilton and Washington had a gay relationship. Kramer's opinions were quoted in print in January 2010, in New York magazine and the New York Post.

There are, however, no indications of transgressive desire in the two men's long correspondence, any more than there are between the (physically unprepossessing) Madison and Jefferson, ten years his senior. In fact, as Washington's aide-de-camp and unofficial chief of staff, Hamilton often chafed under his chief's command, complained about him to his father-in-law, and eagerly seized an opportunity to resign when Washington lost his temper. The two later reconciled, and over time Hamilton regarded his chief with more affection. Upon hearing of Washington's relatively sudden death in 1799, he wrote to Charles Pinckney, “My Imagination is Gloomy my heart sad.”Footnote 72 He was never contemptuous of the man, as Vidal's Burr represents him to be (and as Aaron Burr actually was).

The concepts of homosociality and patriarchy are absent from Kramer's critical apparatus.Footnote 73 One could accept and apply George Haggerty's arguments about the polyvalence of the word love to Hamilton's letters without claiming that – despite his adoring wife, many children, Mrs. Reynolds, Angelica Church, and Lothario reputation – “Hamilton was gay.” What Haggerty says of Stephanson seems applicable to Larry Kramer and Gore Vidal as well: their “range of sexual identities is riddled with late twentieth-century assumptions.”Footnote 74

In fact, there is a similarity between the gay rumor and the monarchist rumor. Both assert that Hamilton secretly and essentially was something that, for most of his life, he appeared not to be. Of Hamilton's controversial speech at the Constitutional Convention, when he suggested an elected President to serve “during good behavior” and subject to impeachment, Chernow insightfully writes, “Till the end of his days, opponents dredged up the speech as if it embodied the real Hamilton, the secret Hamilton, as if he had blurted out the truth in a moment of weakness.”Footnote 75 This mode of thinking suggests reliance upon a depth hermeneutic – a belief in the superior truth value of any latent or seemingly concealed narrative merely because it is below the surface.

HAMILTON WAS HOT

“Hamilton is the only Founder whose sexual appeal has transcended the eighteenth century,” quipped filmmaker Ric Burns at a 2004 New-York Historical Society panel entitled “Whose Hamilton?”. Testimony to Burns's observation abounds on the Internet. Here Hamilton's heterosexual appeal survives. He seems to be particularly popular among young women, such as college students and women academics (the latter is what prompted Burns's quip). One admirer writes,

Man, looking closely at a ten dollar bill, I noticed that Alexander Hamilton is pretty hot. I mean, beautiful eyes framed by bold eyebrows, great skin, a strong jawline, perfect chin, and very kissable lips. Yes, that man was quite a hottie.Footnote 76

On another website, a young woman confided,

I'm posting two little known portraits of one of my historical crushes and fave dead guys, Alexander Hamilton. The sensual mouth he has in these pics almost makes one want to swoon … Imagine being the lucky woman (or women in his case) to kiss that mouth. He looks so divine in blue!Footnote 77

In another post entitled “Alexander Hamilton Was Hot,” Angie confided to her readers,

About seven years ago I was in New York for a wedding when I walked by Alexander Hamilton's grave at Trinity Church and told my friend Jennifer that I thought Alexander Hamilton was hot … why the Alexander Hamilton story? Because I'm a gigantic dork with next to no life, tonight I'm watching Alexander Hamilton's American Experience thingie and I'm super-excited about it.Footnote 78

This post inspired a sympathetic comment from dav (female):

From the faint memory of my American history, I'm thinking Hamilton was a pretty good guy though he and Jefferson fundamentally couldn't get along … Oh, and he was totally hot.

Anonymous commented,

HAHAHAH! i've always thought he was soo hot but no one agreed with me!

On her Facebook page, a student named Alex began a long discussion with the following post:

Let's face it, he was pretty freakin' sweet. He was a cynical, illegitimate son of a rich nobleman, he was raised in poverty. and he was the only founding father who wasn't technically american. not to mention, he got killed in a duel A DUEL! HE'S AWESOME! To clinch my deal: find one of the new 10$ bills. Look at his portrait: have you ever seen such a foxy founding father? I say Nay. Alexander Hamilton was HOT. HOT and a BADASS. Who's with me?Footnote 79

The long discussion ended with this post from a Hong Kong admirer named Crystal:

Completely and utterly in love with him. Despise Aaron Burr with passion.Footnote 80

History and biography are present in these encomia, but clearly Hamilton has become a celebrity. The romance of his life story increases his allure. Once historical figures become transhistorical celebrities, their popularity is enhanced, but their complexity and contradictions are diminished. We are accustomed to a kind of celebrity necrophilia in which living people fall in love with dead movie stars and entertainers. James Dean and Marilyn Monroe are icons of doomed desire. It is all the more interesting, therefore, that a historical figure whose voice, smile, and physical movements have long been extinguished and were never recorded on celluloid can continue to generate an erotic charge.