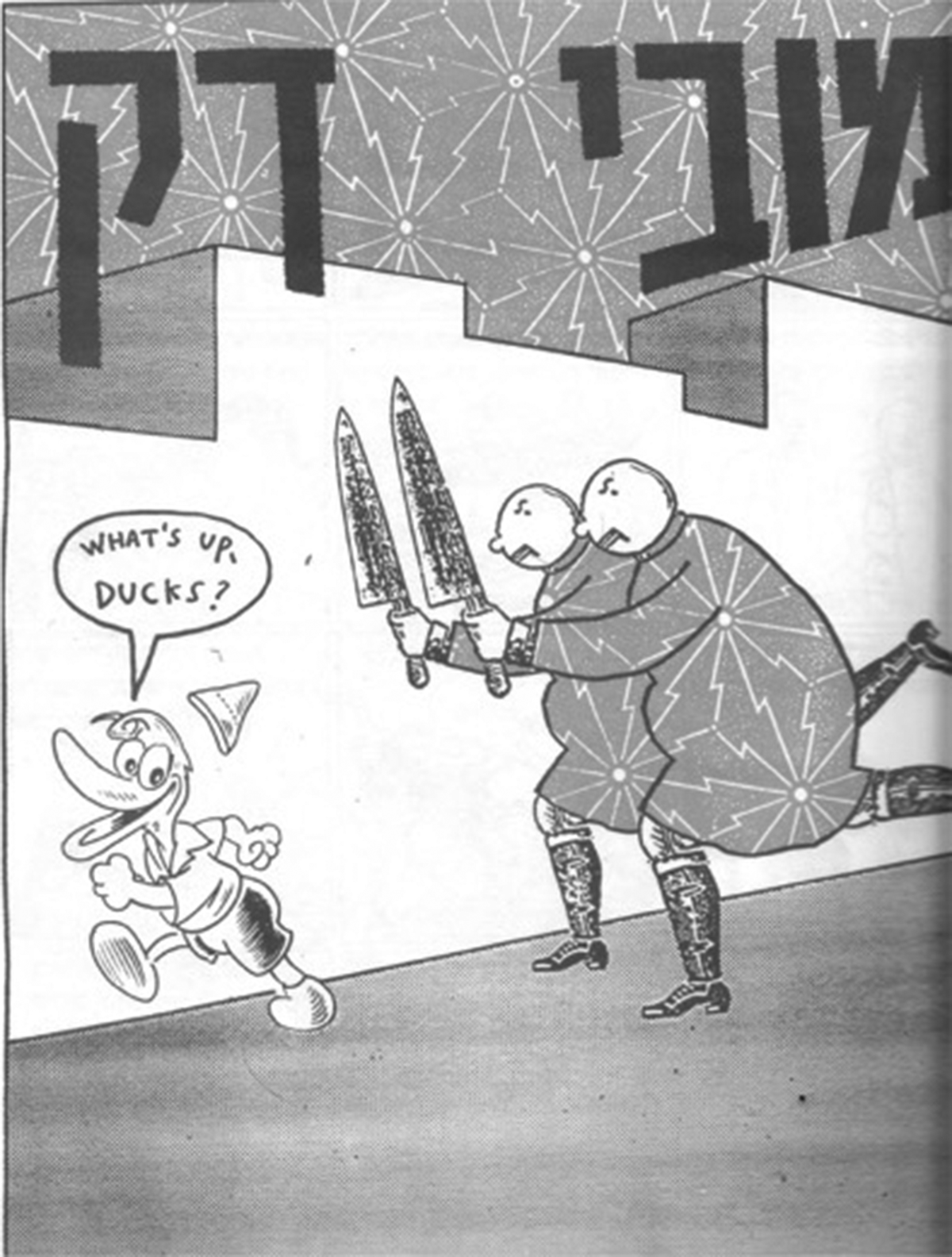

If this duck seems a bit rattled, it is for a good reason. Its creator, Israeli comics artist Dudu Geva, had just finished two rounds in a legal battle against the Walt Disney corporation. In 1991 Disney sued Geva for publishing a snippet from his forthcoming monograph The Duck Book in the local paper Tel Aviv. The majority of the book centered on Geva's familiar duck character (Figure 1) – a figure he turned to frequently in the 1980s. Such a book would not have roused attention from Disney, had it not been for one eighteen-page strip within it called “Moby Duck”: The duck in that story (and the one that appeared in the snippet) looked a lot like Donald Duck with a forelock and a hat. Two days after the appearance of the snippet in Tel Aviv, in the early hours of Sunday, 22 September, the phone rang in Geva's apartment. “They wake me up at seven in the morning,” Geva later recalled in an interview, “and tell me: ‘this is the office of Nashitz, Brand, and partners’. It took them half a minute to finish all their names. ‘Do you know you violated the copyright law when you used Donald Duck in your story?’”Footnote 1 Geva kept his cool until he got the subpoena “and was effectively knocked out.”Footnote 2 The case of Disney v. Geva was underway.

Figure 1. Dudu Geva's duck, from the cover of Dudu Geva, The Duck Book (Tel Aviv: Hozaat ha kibuz ha meuhad, 1994).

Disney's accusations against Geva revolved around questions of originality, of authority to use universally familiar icons within artwork, and of constraints on cultural and social critique within translation and adaptation. More than a mere judicial curio, the high-profile lawsuit was followed by the Israeli press as local intellectual and artistic circles mobilized to mount Geva's defense. This milieu interpreted the legal case along clear fault lines, identifying it as an assault of American commercial interests on the creative freedom of the Israeli artist. A transnational duck fight ensued – one in which, predictably, Disney would win, and Geva would lose. Few Americans outside the Disney legal department even heard so much as a flutter of wings from the whole affair. But in Israel, the sight of Geva's beaten duck galvanized his milieu of Israeli artists and writers to lodge complaints: complaints against the reach of US corporate power, against the suffocation of hybrid cultural creation, and against the Israeli courts that, for reasons of cultural gatekeeping, let Disney win.

The stakes of the Disney v. Geva case map onto the broader study of cultural Americanization. If during the 1960s and 1970s cultural historians examining American power abroad frequently treated Americanization as a form of cultural imperialism, from the 1990s onwards scholarship framed American cultural relations with other societies more in terms of “transculturation.”Footnote 3 These works framed the presence of American culture abroad not as an indication of American imperialism, but as a process by which other societies adopted, acculturated, and molded American cultural items and ways of doing things and tailored them to suit local traditions – sometimes affecting American culture in return, or creating a broader Western or global culture. This corpus highlighted the improvisational, organic, or unintended ways in which non-Americans chose and picked different American cultural idioms for their own use.Footnote 4

But how free was that process of picking and choosing? Historian Mel van Elteren questions “whether all consumers have the same access to the possibilities of creativity” entailed in this process of transnational acculturation.Footnote 5 Similarly, Richard Kuisel warns that the focus on “how recipients selected, adapted, and transformed what America has sent them” should not lead historians to ignore “American power.”Footnote 6 Whether in explicitly political terms or in market terms, producers (such as Geva) who practiced translation, adaptation, and quotation did not enjoy the freedom of unbridled creativity: their work remained embedded within power relations. This article uses the case of Disney v. Geva to demonstrate the sometimes unpredictable local constraints a non-American faced when turning to use an iconic duck from the American cultural toolbox.

To do so, it follows in the path of recent studies that locate Disney (and its trademark duck in particular) within critical readings of American power in the world.Footnote 7 Concern with Disney as an agent of empire can be traced most famously to Ariel Dorfman and Arman Mattelart's 1971 study How to Read Donald Duck in Chile. Disney sued Dorfman and Mattelart in an attempt to block the distribution of their work.Footnote 8 Their book defined Donald Duck as an agent of global capitalism and cultural imperialism, and repudiated the growing American influence over Chilean society. With the backdrop of the 1973 CIA-backed coup that overthrew the democratically elected Salvador Allende and instated the oppressive regime of Augusto Pinochet, Dorfman and Mattelart's book expressed a rallying cry against Uncle Sam's neocolonialist interference in Chilean affairs. Donald Duck, in that arrangement, stood as an icon of imperial invasion.

American power worked differently in Israel. While Dorfman and Matelart identified American influence as strengthening authoritarian and antiliberal forces in Latin America (in line with broader critiques of cultural imperialism emerging in the 1960s and 1970s), some senior Israeli scholars argue that Israeli liberals embraced Americanization’s effects on Israeli life. Sociologist Uri Ram suggests that “Americanization is concurrent with the cosmopolitan, liberal (and in part post-Zionist) ethos that took root in Israeli middle-class culture since the 1980s,” and that “Americanization did not meet in Israel with the kind of open hostility familiar from other regions of the world.”Footnote 9 Historian Tom Segev went further in framing Americanization as a force that would counter Israeli ultra-nationalism, claiming that this “American spirit, which produced the Camp David agreements between Israel and Egypt [in 1977 and 1979], would later lead people to feel they had had enough of the occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.”Footnote 10 Segev was not alone in this assessment: during the 1990s many Israeli liberals hung high hopes on American influence pushing Israel toward a compromise and toward a peaceful resolution of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Renowned Israeli intellectual Amos Elon claimed in 1998 that “the Americanization of Israel entails many positive things,” detailing increasing pluralism, secularism, and other effects that save Israel from “becoming a fascist or theocratic society.”Footnote 11 Even if this view was shaped at least to some degree by a skewed understanding of the Oslo process framework, it was prevalent among the circles of the liberal and secular left – who identified American influence as a reforming and liberalizing element in their lives.Footnote 12

Was that the case? In material terms, no country received more material support after World War II than Israel did. This unparalleled support was partially a result of successful lobbying by pro-Zionist and pro-Israeli organizations.Footnote 13 Besides material support, American diplomats shielded Israel in the international arena, by repeatedly vetoing proposals in the United Nations to censor Israel for its policies of territorial expansion.Footnote 14 Many Israelis understood cultivating US material and diplomatic support as an important national mission. And yet Israeli reactions towards the dynamics of American support were not limited to gratitude alone. An underexamined side effect of continuous US support was that some Israelis saw the gestures of flattery and lobbying Israeli officials performed to gain American support as a form of groveling. In specific instances when Israeli authorities served American economic interests at the expense of Israeli citizens, Israelis protested. Two earlier examples where Israeli campaigners attacked what they saw as their state's illegitimate financial flexing to accommodate Americans at the expense of Israeli cultural producers and entrepreneurs are the government's decision to classify Otto Preminger's Exodus as an Israeli film in order to facilitate direct governmental assistance in 1959 (sparking the envy of Israeli producers), and the governmental and municipal investments in the construction of the Tel Aviv Hilton, which opened in 1965. Such protests, usually expressed in Hebrew only, often expressed local pride in a socialist Zionist ethos, and a condemnation of American culture as superficial, materialistic, and corrupting.Footnote 15

In his rich study of Israeli perceptions of Americanization, Maoz Azaryahu frames Americanization in purely discursive terms, suggesting that Israelis took positions on Americanization mostly to clarify their views on domestic questions relating to Israel's evolving character. While that approach reveals much about Israeli society, the downside of such an assessment is that Americanization becomes void of Americans – removing American interests from the equation.Footnote 16 The case of Disney v. Geva complicates that dynamic. Geva made his critiques of American culture from his position as a self-avowed admirer of underground comics and American counterculture more broadly. He treated American vernaculars as his own – and he got convicted for it. At the same time, unlike previous Israeli protestors against the ills of American influence on Israeli life, Geva ridiculed pathos-laden exultations of the virtues of the Zionist ethos. He boasted that at the age of fifteen he traded his signature of David Ben Gurion for a collection of MAD magazines.Footnote 17 The lawsuit, however, demonstrated to Geva that he had no right to pick and choose the icons he could use in his work as a visual artist. The dominance of the American corporation in the global copyright regime, coupled with the strict national paradigms adopted by the Israeli court to decide against him, constrained (rather than expanded) his rights.

Furthermore, an examination of Geva's work also troubles arguments by Israeli liberals claiming the US acted mostly as an element weakening Israeli militarism and leading the country to peace. Geva (Figure 2) had no delusions about the benevolence of American power. He identified the United States as Israel's enabler in policies of occupation and violence. Scholarship on US–Israeli relations clarifies that admiration of Israeli military prowess was central to American fascination with the country – partially in response to the American failure in the Vietnam War. The shared history of settler colonial expansion between the two societies appealed to many Americans, and the rising affinity between the American right and the Israeli right further bolstered the profoundly militaristic nature of US support to Israel.Footnote 18 This reality was not lost on Geva – who remained suspicious of both American and Israeli power.

Geva's body of work, published in more than thirty-eight books and collections and countless newspaper strips in a career stretching over three decades, produced sharp commentary on Israeli life. It ridiculed and poked holes in Israelis’ blind admiration of military figures, in Zionist fabrications that erased the existence of bustling Palestinian life on the land before Zionist settlement, and in the boastful materialist consumerism of late twentieth-century Israel.Footnote 19 But he also had little patience for American pretences of benevolence and altruism. As part and parcel of this critical worldview, he recognized and addressed the hypocrisy and violence of Israel's American benefactors. Geva was a self-professed socialist, and consistently mocked power. His embrace of the antiheroic and the diasporic, his mockery of Israeli militaristic pathos, and his defiant professional profile (repeatedly fighting with the editors that employed him) marked him as a leading subversive voice in Israel's comics scene.Footnote 20 Geva's iconic status in the circles of Tel Aviv bohemia only grew further after the Israeli courts sided with the Disney corporation against him: soaring the beaten-up duck to the top of the Tel Aviv city hall.

THE AMERICAN SON OF A BITCH FORGOT HIS PLACE

When Geva prepared his defense for Disney's lawsuit, he did not turn to an intellectual-property lawyer. Instead, he turned to high-profile advocate Avigdor Feldman, renowned for representing Palestinians and human rights organizations before the Israeli court. Geva's recollection of his first meeting with Feldman about the case was appropriately graphic, stating that Fedlman’s “mouth filled with saliva and his eyes washed with blood. ‘Who does this Walt Disney think he is?’ he said, and increased my motivation.”Footnote 21 Feldman's own cartoonish recollection was not far off: “Sweaty and frightened Dudu Geva surged into my office … his eyes running in every direction. ‘Walt Disney is after me’, he said in a gasp.”Footnote 22

Geva's indignation stemmed partially from the fact that he was already such a distinctive and renowned figure in Israeli visual culture by the time Disney branded his work a rip-off. An autodidact, Geva started publishing cartoons while in high school in the late 1960s. Deciding he had little to learn at the prestigious Jerusalem art school Bezalel (young Geva was not short on confidence), Geva started working for Israeli state-run television in 1974. Geva made a brief appearance in the national press in June 1975, when right-wing demonstrators gathered around the Israeli television offices to protest its alleged left-wing bias. Geva threw rolls of toilet paper at the protestors, also firing a salvo of “curses in juicy Arabic.”Footnote 23 In the decades that followed Geva's work regularly appeared in the pages of Israel's national and local newspapers. Geva was one of the founders of the short-lived progressive daily Hadashot (News) in 1984, producing satire on its pages until the paper's closure in 1993.

Geva's style was purposefully biting. In the tradition of Dadaism, Geva sought to produce absurd arrangements that would jar and disturb the reader. Israeli cartoonist Ze'ev Engelmayer, a frequent collaborator with Geva, defined Geva's collages as exposing

their own production mechanism. Cut and glued in spontaneous primitivism. Oppositional to the glossy and refined computer drawings, they are closer to street culture and punk (similar to Jimmy Reid's Sex Pistols album covers), [made] in a spirit of subversion, anarchism, invention, adventurism, and enthusiasm.Footnote 24

Geva's priority was not to provide readers with a smooth experience of aesthetic gratification, but rather to push them to consciously consider the meanings of the jarring juxtaposition he presented them with.

This form was not limited to visuals alone, but related to the contents of Geva's work, where he lampooned those in power and centered on forgotten, lowly characters. Contempt for power and authority put Geva at odds with many of the editors under whom he worked over the years, and yet Geva rarely compromised. Towards the end of Geva's life he took his creative independence a step further, by forming groups in collaboration with other, often younger, artists working without editing and without censorship – selling copies xeroxed on A4 sheets they prepared themselves to people on the street.Footnote 25 As Daniel Immerwahr shows, Carl Barks, the self-described conservative who created the Donald Duck comics strips for Dell (under Walt Disney), authored narratives that legitimized Uncle Scrooge's wealth, and had to avoid the themes of sex, death, or physical violence in his cartoons. By comparison, Geva's reluctance to follow an editorial line, and his difficulty holding permanent employment, allowed him to engage all these topics, attacking the mendacity and superficiality of society's winners without romanticizing the pathetic characters he cast as protagonists.Footnote 26 The clash between Disney and Geva, then, was – in the eyes of the Israeli artist and his supporters – not only tied to the specific iconic duck in question, but rather to broader relationships between artists and power.

The litigations lasted two years, first at the Tel Aviv District Court and later before three judges of the Israeli Supreme Court in Jerusalem. The weight of the debate revolved around the Israeli court's textual interpretation of Geva's Hebrew-language comic strip, its meanings, and Donald Duck's function within it. The Tel Aviv District Court relied in its discussion on the 1911 British copyright law, which continued to define Israeli law long after the 1948 expiration of the British Mandate. “The 1911 copyright law clearly states that it is an exclusive right to copy or publish, in part or in whole, a certain work,” the court announced, “and that anyone who commits such a deed that is exclusive to the copyright owner alone … is therefore infringing this right.”Footnote 27 But how did the 1992 “Moby Duck” comic strip fit within the terms of the 1911 law? Geva claimed that as an original artist he integrated “cultural symbols and images into the work in a way that gives them a new, parodist, ironic, or referential status.”Footnote 28 The defense insisted that Donald Duck appeared in only a single story in Geva's magnum opus – The Duck Book.

Throughout most of the book, Geva employed his own duck, first created in 1984 (see Figure 1).Footnote 29 Geva's standard duck was stocky, cheerful, and tragic: “a creature that on one hand amuses people and their children as a Ducky in the bath tub,” said Geva, “and on the other hand, knows his fatal end is to be cooked in orange sauce.”Footnote 30 Geva's longtime friend and journalist Zipa Kampinsky explained that his “ducks lived under the butcher's knife and sang on their way to the slaughterhouse.”Footnote 31 Geva's duck was a pathetic victim that comfortably resigned itself to its bitter end – simultaneously defying both the upbeat message of Disney cartoons and traditional Zionist commitment to the fighting ethos.Footnote 32 Developing that line of thought, scholar Ido Harari defines Geva's duck as “the ghost of the diasporic Jew, that Zionism tried to suppress.”Footnote 33

Geva saw The Duck Book as the swan song of his waterfowl. In a July 1990 Geva exclaimed that he was “putting the duck in deep freeze” since “he bought the farm … his disappearance will surprise no one in the chicken coop.”Footnote 34 The interview, titled “the Duck will die at the end of the month,” described Geva's farewell to his beloved character. The book as a whole was a mixture of original stories featuring Geva's duck, with a great mass of archival material relating in any way to the word “duck” in Hebrew or English. Toilet Duck, the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, and the Australian Duck all nested among its pages.

In his affidavit Geva argued that “Moby Duck,” the comic strip in which Donald Duck's figure was used, was “an independent piece with a special message, not dependent on Donald Duck Comics series. It does not impersonate as a Donald Duck Comics in any way.”Footnote 35 He was right, as the analysis below will show. But it is also true that Donald Duck was a good fit within Geva's career-long devotion to losers. When educator Emmanuel Yafe created the first Hebrew comics in Palestine in 1935, he based it partially on the wholesome, winning figure of Mickey Mouse (though its appearance was much closer to Felix the Cat), broadcasting reassuring educational messages to the children of the Jewish Yishuv.Footnote 36 Donald Duck's chaos, by contrast, chimed with Geva's determination to create characters who fail. Writer Koby Niv, who often collaborated with Geva, explained the distinction between two different casts: “masters” and “ducks.” The masters are “beautiful and smart, knowing how to get by, they go to the right places, they dress up.” But the ducks are mere minions to the masters. Geva's duck repeatedly challenges his station in society but finds disappointment and failure.Footnote 37

Ten days before the district court's verdict, a three-page article in the daily Ma'ariv interviewed Geva alongside the worried and appalled comments of “jurists, writers, and artists.”Footnote 38 All of those interviewed strongly supported Geva's stance. In the interview Geva said that Donald Duck “is the king of ducks as far as I'm concerned. I thought I showed him respect here, until the American son of a bitch forgot his place and jumped a small Israeli duckling.”Footnote 39 Prominent artist and art professor Rafi Lavi expressed his dread of the lawsuit: “As a collage artist I'm frightened to think that first-grade artists like Geva, Yair Garbuz, Michal Ne'eman, and others, will work under the threat of such lawsuits.”Footnote 40 Garbuz declared, “I would rather think it would be an assault on Donald Duck if he would not have appeared in Geva's book.”Footnote 41 Echoing the very same sentiments in his court deposition, Geva argued that any limitation on his ability to use quotation of images or symbols within his work would be a breach of his “creative freedom and right of expression.”Footnote 42

The defense tried to assert that Geva's use of Donald Duck stood in the realm of criticism “in artistic ways, as a parody, not necessarily as a critique of the item [Donald Duck] on its own, but also in the service of social critique.” Much depended on the breadth allowed by the court to the word “critique.”Footnote 43 On 29 April 1992 the district court announced its decision. Judge Vinograd decided that the ultimate failing of the defense came from Geva's own mouth. “After all,” said Vinograd, “In his own deposition regarding Donald Duck, he [Geva] said that he used him in his story ‘out of respect to Disney's duck character, that is one of my childhood heroes, one of the standing pillars of the duck nation in particular and Comics culture in general.”Footnote 44 In other words, Vinograd decided that the fact that Geva liked the duck refuted Geva's claim that the work represented a critique.

“My wings have been chopped. A sad day for ducks,” declared a disappointed Geva to journalists after the verdict was read. Geva was fined 9,000 new Israeli shekels for court expenses.Footnote 45 Feldman later recollected that “the somewhat humoristic tone I adopted for the argumentation rolled helplessly around the court like a crushed Coca Cola can.”Footnote 46 Geva and Feldman decided to appeal to the Israeli Supreme Court in Jerusalem, though Geva was pessimistic. “The duck is an animal that lives with the sword on its neck,” said Geva in an interview before the discussion in the Supreme Court; “he will be very surprised should he be vindicated.”Footnote 47

Disney's sanctimonious arguments only frustrated Geva further. Having reviewed the story of “Moby Duck” in full, including a caption portraying Moby Duck copulating with two chickens, the Disney lawyers announced they would not agree to any form of settlement, as the work “diminished Disney's moral and family values.”Footnote 48 Obviously losing patience with anything Disney by that point, Geva asserted, “Walt Disney himself, there was a biography about him that says he fucked under-aged girls, this educational character.”Footnote 49 Feldman defined the fact that Geva lost the case because he declared his love for Donald Duck (and so could not legitimately claim to use Donald Duck within a critique that would constitute fair use) “a parody not even the great Geva himself could have invented.”Footnote 50

HERMAN MELVILLE IN HAIFA

What did Geva try to say in “Moby Duck”? An examination of the cartoon's style and content helps illustrate Geva's motivations. “My work,” Geva explained in court, “took Walt Disney's original figure and added to it the Tembel hat and the forelock of the artist Dosh, to create a kind of ‘Srulik Duck’.”Footnote 51 Some explanation might be in order. “Srulik” is the name of the most iconic comics character in Israeli history. Created by the Hungarian-born caricaturist Kri'el Gardosh (Dosh), Srulik was the fictional poster boy of the young, optimistic, friendly, and hardworking Israel (Figure 3).Footnote 52 Srulik, according to Israeli comics researcher Eli Eshed, became “the ultimate symbol of Israel, or of how Israelis (or at least a certain type of Israelis) would like to see themselves.”Footnote 53

Figure 2. Dudu Geva, 2005. Photograph by Aharaon Geva, his son. License link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:GNU_Free_Documentation_License,_version_1.2.

Figure 3. “Srulik” in the museum of cartoons and comics in Holon, Israel. Photograph by Yair Talmor. License Link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:GNU_Free_Documentation_License,_version_1.2.

A direct translation of “Tembel” hat (the hat on Srulik's head) would mean “Dufus” hat. The official website celebrating Israel's sixtieth anniversary stated that this simply and cheaply made hat was “a symbol for working the land.”Footnote 54 Why, then, did Geva mix the most prominent Zionist icon (Srulik) with Donald Duck?

In Understanding Comics, comic artist Scott McCloud defines “icon” as “any image used to represent a person, place, thing, or idea.”Footnote 55 By juxtaposing Donald Duck with Srulik within the “Moby Duck” story, Geva intended to jar the reader through the clash of multiple ideas that had never been mixed before. “Moby Duck,” said Geva,

is in fact a collage that is based entirely on quoted materials that are woven together to a whole with its own internal logic. The story is a parody on Moby Dick by Herman Melville, with sketches by Israeli artists of the 1950's, wood prints of the 19th century, cook books and medicine books, drawings by Beardsley, the original drawings published in the first Moby Dick, various other Comics, the Agam Water Fountain in Dizengoff, and computer catalogues.Footnote 56

McCloud defines the style of Carl Barks, the creator of the Donald Duck comics, as one using “gentle curves and open lines” to convey “a feeling of whimsy, youth, and innocence.”Footnote 57 By contrast, Geva's style in “Moby Duck” was far more eclectic and chaotic, ranging from deliberately expressionistic lines through neurotic quill lines and uneven lines, to jazzy designs that convey irony and struggle. Donald Duck was out of his element in this story, no longer himself. Geva took Donald Duck far away from home, turning him into a dirty Sabra trickster.

Like Herman Melville's classic novel, “Moby Duck” is a tale of the hunt for the title character. While Melville's Captain Ahab tries to kill the great white whale, in Geva's story a pair of butchers named Max and Zax desperately try to slaughter Moby Duck. But Moby Duck repeatedly escapes their blades in the fatal moment, causing the butchers to lose limb after limb with each attempt. The backdrop is that of Israel's growth. The butchers open shop in the early days of Israel's independence. Through the decades their shop grows from a neighborhood business in the port town of Haifa to become a computerized modern corporation. The business continues to expand. Much unfortunate poultry has passed under the butchers’ mechanized production line, yet all the while the butchers remain incensed about the one that got away: Moby Duck (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Opening page of “Moby Duck” in Dudu Geva, The Duck Book (Tel Aviv: Hozaat ha kibuz ha meuhad, 1994). The published figure bares reduced likeness to Donald Duck compared to Geva's first version – due to the court's decision.

Like the whale, Moby Duck remains a mystery character. Even from a few glimpses through the strip it is clear that he has not changed during those decades of Israel's development – forever wearing the same Tembel hat. While Captain Ahab finds his death in the ocean's deep, Max and Zax roll their wheelchairs in despair into the fountain in Dizzengoff circus in Tel Aviv, drowning themselves into certain death. Geva's narrator is not Ishmael, but rather a Salami sausage called Israel “Srulik” – a direct reference to Dosh's famous character.

Converting Srulik to baloney, Geva was clearly eager to lampoon the clean-cut image of the Israel that Srulik represented.Footnote 58 In this local lens, “Moby Duck” engaged a conversation between Geva's duck and Dosh's Srulik, and between distinctly different ideological and professional approaches to making comics in Israel.Footnote 59 Srulik did not fare better than Donald Duck in Geva's treatment. “Srulik Duck” – to quote Geva's term – suggested that Donald Duck's forced naivety, and that of Srulik, each in its way, peddled idyllic fantasies that needed debunking. But why did Geva not busy himself with embarrassing Israeli iconic characters alone? How did Donald Duck fall victim to Geva's iconoclasm? To answer this, we need to understand Geva's broader engagement with American idioms, icons, and narratives in his work.

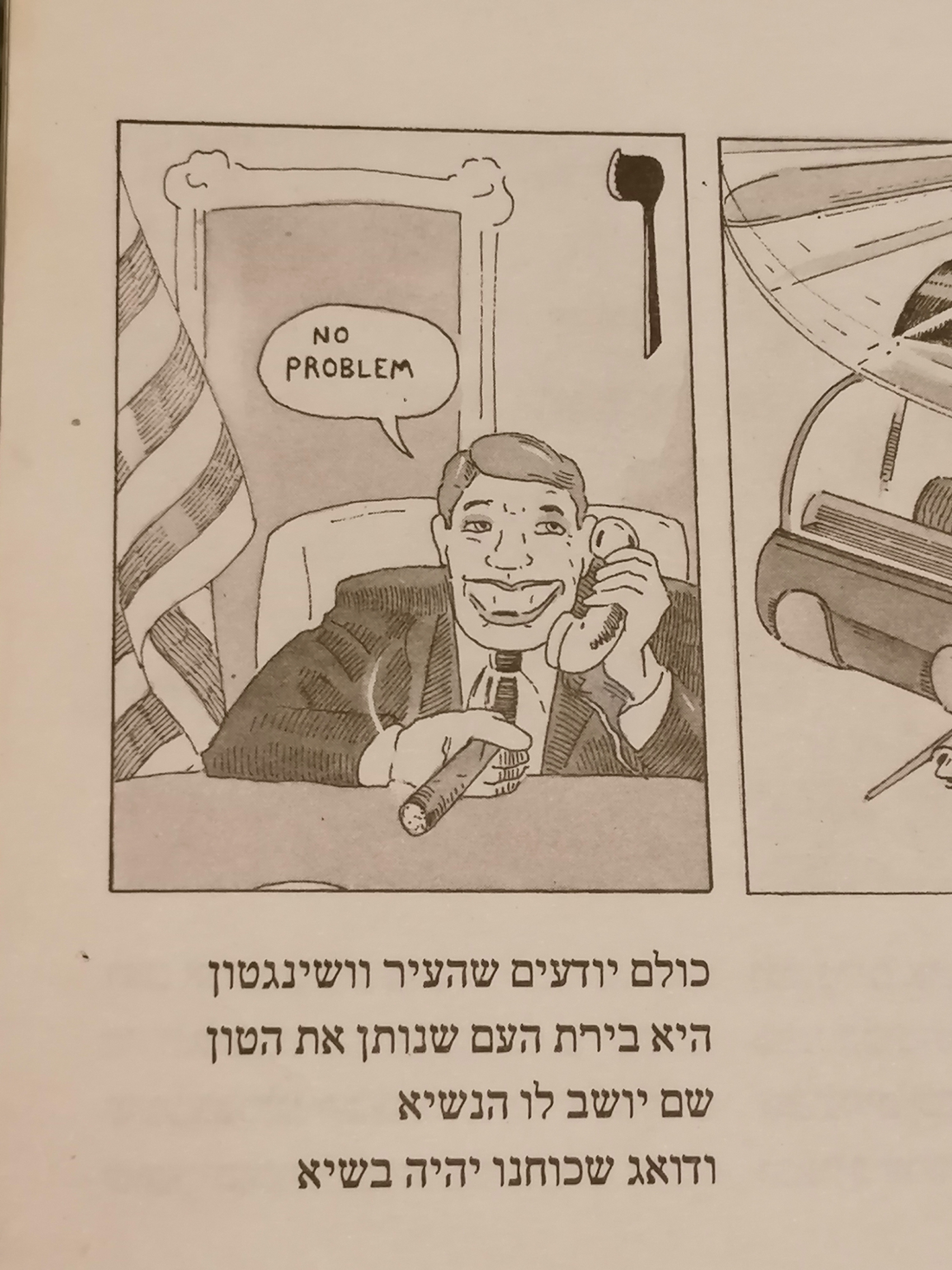

Geva's work did not routinely address geostrategic matters. But among Israeli commentators, Geva was uniquely willing to question the notion that American support for Israel was a good thing. The military and political facets of US–Israeli relations are engaged most concretely in his comic strip titled “ABC: Our Security.” The five-page arrangement is divided to twenty-two panels, one for each Hebrew letter. Fashioned after language-learning books, each caption presents a Hebrew letter and a word that starts with that letter, in a four-line rhyming poem. The overarching similarity is that all the words taught are war-related, and all lyrics are idyllic in their nature, even when the graphics exhibit macabre scenes of smashed corpses and heaps of body parts. The only letter that escapes the fray of battle is the letter vav, which takes the reader from the missile helicopter straight to the Oval Office: “Everybody knows that the town of Washington / is the capital of the people who set the tone / there reigns Mr. President / making sure our power suffers no dent” (Figure 5).Footnote 60

Figure 5. Detail from Dudu Geva, “ABC: Our Security” (“Aleph Bet Bit'honenu”), in Geva, Deserted Thorn (Dardar ba Midbar) (Jerusalem: Adam, 1984).

The image reveals a Ronald Reagan-esque figure with a cigar in one hand and the phone in the other. The Stars and Stripes hangs to its right. The generic President smiles as he speaks into the phone, blessing the violence Israel unleashes throughout the page with a succinct “No problem.” Geva's Hebrew lexicon of Israel's security fetish identifies the American President as the willing enabler of the carnage and buoyant nationalism celebrated in the neighboring sketches. Israelis often took pride in American admiration of Israel’s military exploits.Footnote 61 In comics form, Geva audaciously called out Israeli militarism and American careless support for Israel's vast military apparatus, in ways that very few of his contemporaries dared to do.

Geva did not articulate an explicit political program. His entire body of work represented an effort to champion the loser and ridicule society's winners – an instinct that clashed with the Zionist ethos of heroism and triumph.Footnote 62 But he did not produce work about daily events. Meir Schnitzer, an editor who worked above Geva in the daily newspaper Hadashot (News) remembers the failed attempts to persuade Geva to fit the frame of a classical political cartoonist.Footnote 63 Rather than condemning particular individuals or critcizing specific policies as a political cartoonist might, Geva followed a more anarchic line, exposing and ridiculing pathos wherever he found it.

HUMOR I'M STEALING

Whereas Zionist artists traditionally liked to project Israeli culture as confident and coherent, Geva used the image of an enticing and dominant America to question Israeli assumptions about the coherence of their own national identity. A good example of that dynamic is the work Geva co-authored with writer Koby Niv, titled Ahalan and Sahalan in the Wild West. In that narrative, a pair of Israeli bums embark on a screwball American journey – from stagecoaches to casinos through being tortured by commie pigs – finally winning (together) the presidency after kissing babies with Barbara Walters and embarrassing Ronald Reagan in a presidential debate by pointing out that his fly was open on live television (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Detail from Dudu Geva and Koby Niv, Ahalan and Sahalan in the Wild West (Tel Aviv: Adam, 1987).

Hebrew terminology and Israeli geography pop up throughout their odyssey, dissolving the boundaries between Israel and the US, while at the same time emphasizing the awkwardness of this cultural mix.Footnote 64

Geva lampooned the awkwardness inherent in the uncomfortable translation of American soap operas, westerns, musicals, private-eye narratives, and superhero films into Hebrew (with a touch of Yiddish) and their transplantation into an Israeli setup. By consistently underlining the limits of cross-cultural adaptation, Geva, in stories like “Broken Hearts in the City of Dreams” (soap), “West-Duck Story” (musical), or “A Miracle in the Town” (western), exploited a comedic space between genres relying on pathos and sincerity, and an Israeli cast of characters that never fail to disappoint such lofty expectations.Footnote 65

Geva was immersed in and enamored with American cultural idioms, even as he sought to ridicule some of their formulaic characteristics, and saw it as his mission to create independent Israeli work. The Israeli artist credited much of his inspiration to the American comics he grew up on. An episode Geva shared with the readership of Ha'aretz in 2004 revealed his momentous decision as a fifteen-year-old kid: to trade his vintage original signature of Israel's founder David Ben Gurion for a collection of MAD magazines. Geva expressed his “thanks both to Ben Gurion and to those crazy guys in New York, whose humor I'm stealing to this very day.”Footnote 66 Geva, like many in his cohort of Israel's journalistic circles in the 1970s and 1980s, saw American counterculture as his inspiration.Footnote 67

Geva found in American counterculture the creative tools with which to ridicule American society, and the related Israeli dream (intensifying from the mid-1970s onwards) of “making it big” in the United States.Footnote 68 This was not a uniquely Israeli process: modes of expression and organization developed in the US were often mobilized by non-Americans against what they perceived as the unifying aspect of Americanization.Footnote 69 While he reserved a great admiration for the MAD magazines of the 1960s and 1970s, Geva was also weary of the implications of US dominance on Israeli society. He consciously and willfully adopted features he identified as American-made, but he also understood American culture as an intrusion: “We have changed in 50 years from a modest, socialistic society of values … the entire world moved as well, America conquered the world.”Footnote 70

Geva's statements can be contextualized in a longer trajectory of Israeli criticisms of American imperial conduct. Appearing to resist the US allowed Israeli speakers to reaffirm their sense of local patriotism and independence from foreign influences. Israelis’ contempt for the US was often expressed in Hebrew, for Israeli consumption. This dynamic took many examples over the decades: ranging from the 1961 travel notes of popular novelist Hanoch Bartov, through the cinematic narrative of popular filmmaker Uri Zohar in 1967, to the 1991 pop song by Rami Fortis lamenting America's centrality in popular imagination, to name but a few examples. Official Israeli state actors often fed Americans stories about Israeli gratitude – though here, too, there are important exceptions – like Prime Minister Menachem Begin's 1982 insistence that Israel is not a “banana republic” that would follow American dictates. In the twenty-first century, critics from the Israeli left expressed despair at American irresponsibility and aloofness as US continued to furnish material and diplomatic backing to the policies enacted by the Israeli right. Even a fleeting examination of Israeli culture through the decades reveals a range of expressions of alienation or contempt towards the US or towards Americans, ranging from the playful to the ideological.Footnote 71

Geva ridiculed Israelis who nurtured fanciful dreams about making it big abroad. This ridicule stemmed in part from a sense of national pride related to his experience coming of age after Israel's period of triumphalism between the 1967 war and the 1973 war.Footnote 72 In 1971 a twenty-one-year old, recently discharged from his mandatory military service, produced an English-language poster for the Publicity Department of Israel's Ministry of Education, which was intended for audiences abroad. The poster, advertising “Israel: Real, Free, and 23,” was stylistically consistent with a hippy aesthetic, and packed with swirling lines and rich, bold color.Footnote 73 Geva's collaboration with state authorities did not last into his later years, but he retained a sense of local pride. In a 1983 interview Geva spoke of the importance of local artistic production: “some of the Comics artists here [in Israel] work with the goal of reaching Europe, so some publisher from abroad will buy their work. That's their ideal.”Footnote 74 Geva continued, declaring, “I don't care if what I do won't get abroad. I care about kids appreciating the place they live in and not aspiring to be a piece of Europe in the middle of the Middle East.”Footnote 75 In the Israeli context, Geva's sentiment of anti-provincialism might have been shaped partially by the cross-generational imperative, central to Zionist dictate, of diaspora rejection. According to classic Zionism, any attempt to leave the country mounted to a hopeless attempt to escape the Israeli's assumed primordial connection to Israel – and judging by these statements Geva stood by that principle.Footnote 76

And yet, if in interviews Geva spoke of proud localism with a degree of pathos, his artistic work poked holes in that very pathos. In 1985 the cartoonist published a story titled “The Incredible Story of Ya'akov Ben Susi.”Footnote 77 In this strip Geva unfolded the formulaic rise and fall of a young man who left his family in the south of Tel Aviv for the US following promises of fortune, glamor, and power, culminating in the inevitable recognition that there's no place like home – except that there was a defining twist. The narrative's chronology follows the familiar template that was presented in a swath of Israeli films of the period: the young man seeks success and fame; discovers that materialism does not compensate for one's true roots, needs and family; and, sobered now from his fanciful dreams, returns home, where the heart is.Footnote 78 While the shadow of this narrative template runs through Geva's “The Incredible Story,” there is a deep-seated sarcasm to the narrative, which completely subverts the rules of the genre.

The story begins with Ya'akov Ben Susi receiving a mysterious letter – “I am your rich uncle Shlomo. Come meet me at six.”Footnote 79 The yarmulke-wearing Ya'akov meets his cigar-smoking uncle in a bar, where his uncle tells the boy that he wants to make him “a tempting proposition.”Footnote 80 Two panels forward Ya'akov is already crossing the Atlantic with his newly discovered uncle, raising a toast to “the joint venture” – no yarmulke in sight.Footnote 81 From here on he becomes the brightest star of Wall Street and the toast of Manhattan. His time is spent between a Barbados weekend and an IBM takeover, until, inevitably, “the formerly Yemenite boy receives a phone call from the world's most powerful man.”Footnote 82 Ben Susi now accompanies the President to various global summits, advising him on the most critical matters. Soon after that James Benson (Ben Susi changed his name to English) starts noticing an annoying buzz in his left ear.

The buzz accompanies Benson's fall. He increasingly alienates those around him, haunted by the premonition that his ears are telling him something important about his identity. When it all tumbles down Benson escapes America and begins to aimlessly wander the world. Finally Enri (James – Jose – Ya'akov) is revealed again, working a news stand in Paris. The buzz in his ear still drives him crazy. It is then that he offhandedly hears Israeli tourists speak the words “Shma Israel.”Footnote 83 This marks the climatic last stage in the character's development: Ya'akov (the original Hebrew name returns) leaves it all behind and boards a plane to Tel Aviv. Tears run down his face as he prepares for landing: “Finally he has roots, a past, an identity, a place,” reads the narration.Footnote 84 Geva's narration exposes the easy slippage from proud localism to xenophobia: “He always knew that something about his life among the gentiles was essentially rotten. He never did like their rude laughter and foul smell.” Making his way to the old Tel Aviv home, Ya'akov is thrilled to see “many things have changed – but here is the place, here is home!” As he approaches, his mind races: “And here is 6 Warriors Avenue, here is Rahamim's overpriced grocery shop, here is the tree we climbed as kids …” Until Ya'akov is unceremoniously confronted by the fact that his old childhood home has been replaced by a bank branch. The next caption announces to readers, “The Ben Susi family doesn't live here anymore” (Figure 7).Footnote 85

Figure 7. Detail from Dudu Geva, “The Incredible Story of Ya'akov Ben Susi,” in Geva, Tiny in Pants (Dardas BaMikhnas) (Tel Aviv: Adam, 1985). Ben-Susi looks at where his old home used to be, only managing to blurt out, “Bank?”

The family have sold the house to the bank for a wad of cash and moved to the suburbs. The dad has opened a profitable candy business and the family are living large, enjoying a vacation in Rhodes, even as Ya'akov stands transfixed at the bank erected where his longed-for childhood home used to be. Ya'akov then breaks the fourth wall, asking the storyteller, “but what about the buzz in the ear?” the narrator answers in the final panel: “the buzz? Well … that's just nonsense. A small formation of ear wax due to hygienic negligence. A little wash would have sorted it all out.”Footnote 86

Ya'akov left his house of little means in a raggedy Tel Aviv neighborhood to become the right-hand man of “the most powerful man in the world,” enjoying the company of beautiful women, endless money, and celebrity status. His only weakness turns out to have been his romantic yet baseless obsession with the supposed importance of his Israeli roots. Ya'akov told himself that he had given up too much for success abroad, changing his identity (and his name), betraying his Jewish and Israeli upbringing in ways which his nature (and his ear) could no longer suffer quietly. But this was nonsense. The problem had nothing to do with Ya'akov's nature or national identity and belonging. Instead, the cruel joke reveals, it was merely a matter of “hygienic negligence.”

Rather than ridiculing the naive and superficial dreams Israelis had about success in the US, Geva's surprise ending ridiculed the romantic presumption that an authentic and dependable Israeli community even existed and was worth going back to. Through this double-edged message, Geva dismissed notions of primordial national belonging, presenting alternatively a world that is as open as it is alien. The family that under the rules of the genre was supposed to be eagerly anticipating the lost child's return was itself enjoying a routine excursion abroad, trying to cheat a Greek waiter out of his tip rather than worrying about the fate of the lost son.Footnote 87 “The Incredible Story” reflects a fluid impression of Israeli identity, one in which it is hard to understand what is essentially Israeli or American, and whether such identity distinctions even carry any meaningful weight. It is this sort of fluid outlook that created “Moby Duck.”

While Geva's work demonstrated fluidity between Israeli and American worlds, the legal process sought stricter logics through which to make decisions. Faced with the hybrid that is “Moby Duck,” the Israeli Supreme Court had no problem dividing American from Israeli. Three Supreme Court Justices convened on 30 December 1993, and delivered the final verdict on Geva's appeal, which, like the district court debate, circled the interpretation of the critique clause in the 1911 law. Quoting the different meanings of the word “critique” from the Hebrew dictionary, the Supreme Court asserted that “with all due respect, the District Court was wrong to apply a negative meaning to the word.”Footnote 88 The Supreme Court accepted Feldman's claim that the term “critique” includes also positioning a work of art in a new context that lights other sides within it, not necessarily negative ones, and so Geva's declaration of affection towards Donald Duck was no longer regarded as self-incrimination.Footnote 89

On the other hand, the Supreme Court turned to ask whether the use of Donald Duck played a vital part in the satirical or parodical content of the story. Its decision on this matter depended on the Court's literary analysis of “Moby Duck.” The justices sat to read the comics. They asserted that the Donald Duck figure in the story “catches the eye, and is perhaps even funny,” which carries a commercial value, but “not a satirical–artistic value, that would justify copying the figure.”Footnote 90 The verdict stated, “The use of Donald Duck does not assist the satirical effect (if such an effect even exists), and there are no distinctive characteristics of Donald Duck or his cultural environment” in the story.Footnote 91 With these cryptic words, Geva was found guilty of taking some of Donald Duck, but not enough of it. The Court found the Donald Duck elements of “Moby Duck” too thin, diluted as they were in an absurd collage with Haifa butchers, Srulik, and a Tembel hat, and so it found no justification for their appearance at all. The Court imagined American and Israeli stories as clearly distinct, and doomed Geva's peculiar duck to legal extinction.

The Supreme Court charged Geva a further $10,000 as the case was closed. “Moby Duck is dead,” declared Geva after the verdict was read.Footnote 92 “He was a nice guy, and now I'll have to throw him to the trash. And so will disappear one of the best Comics stories I've written in my life.”Footnote 93

In truth, however, the story did not disappear. The Duck Book was published in 1994, with “Moby Duck” inside it. Donald Duck was absent, replaced by an approximate (but non-incriminating) portrayal drawn by Geva. The butchers, the scandalous sex scene, Srulik's Tembel hat, all remained in the published story. Alert to the ways the legal case could help promote his book, Geva printed the following message on the cover of The Duck Book, beside the image of the battered duck: “according to District Court decision nr. 2221/91 Donald Duck does not appear in this book, apologies to all.”Footnote 94

DUCK SCARS

On 15 February 2005, fifty-five-year-old Geva died of a heart attack. His death triggered a flood of publications eulogizing Geva and his work. In April 2008 Geva's duck was celebrated as an official symbol of Tel Aviv, and a giant balloon model of the duck was placed to sit on top of the city hall for three months, as part of the city's centennial events (Figure 8).Footnote 95

Figure 8. Dudu Geva's duck on the Tel Aviv-Yafo city hall, 21 April 2008. Photograph by Yair Talmor. License link: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:GNU_Free_Documentation_License,_version_1.2.

Geva's already established reputation as a fiercely local artist was only magnified by his skirmish with Disney. One of the ceremony's organizers stated, “we hope to sometime [take the giant duck] on tour in the U.S., but it appears that Donald Duck sits on top of most of the buildings there.”Footnote 96 A permanent statue of Geva's duck was mounted in a square just steps away from the city hall. Geva's duck was also announced as an honorary citizen of Tel Aviv, joining the company of Albert Einstein, Zubin Mehta, and Shimon Peres on the exclusive list.Footnote 97

At about the same time of the duck's ascension to the roof of the city hall, Disney was on the chase again just seventy kilometers south of Tel Aviv – this time at the behest of the Israeli authorities. The Israeli consulate in Los Angeles alerted the Walt Disney Company to the fact that the Hamas television channel, Al Aqsa TV, operating from Gaza, had used a character dressed like Mickey Mouse who goes by the name “Farfour” within its children show Tomorrow's Pioneers. Farfour, complained the Israeli Foreign Ministry, “preaches hatred” to its audience of children, encouraging them to support armed attacks against Israelis and Americans.Footnote 98 The Israeli Foreign Ministry, aware of Disney's proactive prosecution policy, solicited the corporation's involvement. Diane Disney Miller, Walt Disney's only living descendant, stated, “Of course I feel personal about Mickey Mouse,” and added that Hamas's use of Mickey Mouse was “pure evil and you can't ignore that.”Footnote 99 Eventually, pressure from the Fatah-led Palestinian Broadcasting Agency brought Tomorrow's Pioneers to cut Farfour: his final episode showed the Gazan Mickey executed by an Israeli officer, and replaced in the following season by Nahoul, a bumblebee with a high-pitched voice and no Disney pedigree.Footnote 100 Farfour's story highlights the power dynamics shaping the US–Israeli–Palestinian triangle. Israeli officials enjoy extensive pull with the US government and non-state actors alike, habitually mobilizing them against Palestinian interests.

Yet despite Israelis’ cushy access to American largesse, not all Israeli liberals perceived the US as a benevolent power whose influence would expand civil rights and usher Israel into more peaceful times. Celebrating Geva's duck, and remembering his loss to the predatory Disney corporation, allowed Israelis to sample a whiff of anti-imperialist sentiment. This posture reflected the ambiguous position of Dudu Geva fans: at once both (as Israeli citizens) benefactors of American patronage, and critics of the Israeli militaristic tendencies facilitated by that patronage. While scholars tend to emphasize supposed Israeli enthusiasm and optimism with regard to American influence, the legal case presents an example when the creativity of an Israeli artist met the uncompromising attentions of a litigious American corporation, and those of an Israeli court keen to limit the possibilities of transnational imagination and to uphold corporate rights. The messages emerging from Geva's body of work, ridiculing Israeli militarism, and mocking American power and benevolence, expressed skepticism about the benefits of American patronage, and depicted a hypocritical and materialistic America – rather than one bringing peace and liberty to Israeli shores. Geva's art was informed by American counterculture and cultural icons, but he sought to inspire an identity that would be patently local, and he did so partially in defiance of what he (like some Israelis before him) perceived to be shallow American values. At the same time, the localism Geva articulated was necessarily alternative to the Israeli consensus stretching from the hardline right to the liberal center – defined as it was by subversion against key Zionist myths and a mockery of Israeli militarism. These are the meanings etched into the scars on Dudu Geva's awkward duck.

The author would like to thank Mark P. Bradley, Brooke Blower, Daniel Immerwahr, Gabi Tartakovsky, Daniel Mitelpunkt, the journal's anonymous readers for suggestions and comments on this article, and to Tammy Geva as well as to the Kibbutz Meuhad press for permissions to use Dudu Geva's art in the article. The article is dedicated to the memory of the brilliant Naama Tsal.