No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 February 2016

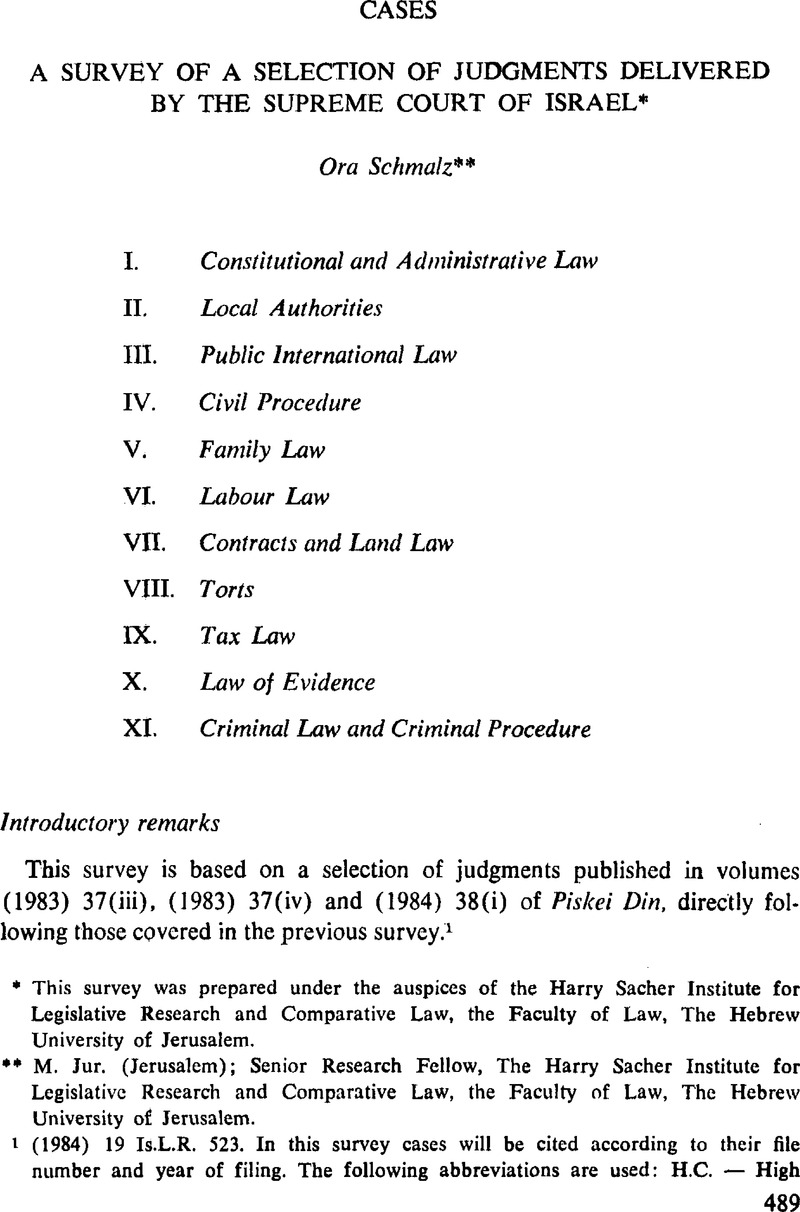

1 (1984) 19 Is.L.R. 523. In this survey cases will be cited according to their file number and year of filing. The following abbreviations are used: H.C. — High Court of Justice; CA. — Civil Appeal; Cr.A. — Criminal Appeal; F.H. — Further Hearing; S.P. — Sundry Petitions; S.T. — Special Tribunal.

2 For earlier examples see: Schmalz, O., “A Survey of a Selection of Judgments Delivered by the Supreme Court of Israel (1983)” in (1984) 19 Is.L.R. 523 at 526 and 588.Google Scholar

3 See text at infra n. 86.

4 Cr.A. 123/83, 38(i) P.D. 813.

5 F.H. 7/81, 37(iv) P.D. 673.

6 C.A. 230/80, 35(a) P.D. 713.

7 27 L.S.I. 117.

8 See: P. Sharon in (1984) 19 Is.L.R. 154.

9 Cr.A. 553/82, 37(iii) P.D. 789.

10 L.S.I. Special Volume.

11 1 L.S.I. (N.V.) 222.

12 F.H. 22/83, The Stale of Israel v. E. Chadria, 38(ii) P.D. 285.

13 H.C. 141/82, 37(iii) P.D. 141.

14 36 L.S.I. 81.

15 12 L.S.I. 85 and 13 L.S.I. 228.

16 27 L.S.I. 48.

17 There are certain restrictions which when not honoured by a party group cause only a partial cut in the financing provided for according to that Law.

18 The exact calculations are here omitted since they are irrelevant to the legal dispute in this case.

19 The exact procedure is specified in sec. 10(e) of the 1973 Law.

20 According to the judgment — on 11 March (the date on which the Law was published).

21 Sec. 4 provides: “The Knesset shall be elected by general, national, direct, equal, secret and proportional elections, in accordance with the Knesset Elections Law; this section shall not be varied, save by a majority of the members of the Knesset.” (12 L.S.I. 85).

22 The petition included additional requests omitted here for reasons of brevity.

23 “Lists” refers to lists of candidates.

24 In Hebrew there is nothing unusual in the use of the phrase “no less bad” and these words appear in the judgment without inverted commas. Although in English it would sound better if these words were translated into “not better”, it seems to me that because of the slight semantic difference between the two phrases it was preferable to use here the words which are closer to a literal translation.

25 The President was then Justice Kahan, and the Deputy President was Justice Shamgar, who has since become the President of the Supreme Court.

26 In the text as published in Piskei Din—see at p. 147—the word “strengthen” does not appear but it seems to me that a printing error accounts for this. The text reads ![]() and it should most probably read

and it should most probably read ![]()

27 H.C. 337/83, 37(iii) P.D. 418.

28 The petitioner was a member of the committee concerned.

29 It follows from the judgment, however, that during one of the Committee's meetings the petitioner and other members of the committee asked the chairman to apply to the Minister and request the relevant report.

30 Free translation from the Hebrew text of the judgment.

31 H.C. 337/81, 37(iii) P.D. 337.

32 H.C. 1/49, 2 P.D. 80.

33 The judgment in the case of Beserano was in favour of allowing the petitioners to continue with their functions, in certain traffic offices, as representatives of their clients. The main reason for holding so was that every person has a natural right to occupy himself with any work he pleases unless there exists a law which forbids to do such work. No such prohibiting law existed with regard to the petitioners' occupation.

34 The grievances of the petitioners in this case may serve as an apparent indication of the need for such revival.

35 I.e. workshops competent to examine vehicles for licensing purposes.

36 Traffic Regulations (Amendment No. 4), 5741–1981, K.H. 1981, p, 714.

37 1 L.S.I. (N.V.) 222.

38 See at p. 350 of the judgment.

39 H.C. 488/83, 496/83, 505/83, 37(iii) P.D. 722.

40 Prisoner's-petition-appeal 4/82, S.P. 904/82, 37(iii) P.D. 201.

41 See at p. 205 of the judgment.

42 Although it seems that such a request to the Judiciary on behalf of the Executive is somewhat surprising, it must be admitted that this is not the first case in which a request of this kind has been successfully made. For a previous similar instance see: E. Amrani v. The Great Rabbinical Court and others, H.C. 566/81, 37(ii) P.D. 1 at p. 9, included in a previous survey, supra n. 2 at 546.

43 The judgment makes no clear distinction between an arrested person not yet convicted and a prisoner who has been convicted. Apparently the Court's opinion on the disputed matter applies to both categories of persons.

44 H.C. 351/83, 37(iv) P.D. 500.

45 The first question was resolved on the ground that according to the wording — at the time—of the relevant order (on which the respondent relied), there was no need for the petitioner to acquire a licence according to the Licensing of Businesses Law, 5728–1968 (22 L.S.I. 232). The questions related to the Planning and Building Law, 5725–1965 (19 L.S.I. 330) in this case remained unsolved.

46 H.C. 59/83, 37(iii) P.D. 318.

47 22 L.S.I. 232. Amendments No. 2 and 3 to this Law concern the issue; see also 28 L.S.I. 104 and 32 L.S.I. 49.

48 For other cases on the subject of licensing see, for instance, those included in a previous survey published in (1983) 18 Is.L.R. 268 at 281–284.

49 I.e. a “regular” licence, not limited to a temporary period.

50 Such remarks by the Court directed to a “winning” party in a legal dispute, though rare, and most probably prompted by good intention, should nevertheless be pointed out as a disputable practice.

51 H.C. 248/81, 37(iii) P.D. 533.

52 The Court referred in this respect to M. Sherf, advocate v. The Central Board of the Chamber of Advocates in Tel-Aviv, and another, H.C. 853/78, 33(i) P.D. 166.

53 The subject of the intervention of the High Court of Justice in the use which the A.G. makes of his discretionary power with regard to subjects of prosecution, is dealt with in some detail in the case of M. Noff v. The Attorney General and others, H.C. 329/81, 37(iv) P.D. 326.

54 “Accuser” is the short term used in section 63 of the Chamber of Advocates Law, 5721–1961 (15 L.S.I. 196), to designate the public bodies and the persons au thorized to file certain charges with Courts of Discipline according to that Law.

55 Apparently the Court regarded this statement as an additional cause for its inter vention with an accuser's discretion. (See a remark in this regard at p. 332 of the judgment in the case of M. Noff mentioned in n. 53, supra.)

56 H.C. 118/83, 38(i) P.D. 729.

57 Some of the details specified in the judgment are omitted here and some are summarized for reasons of brevity.

58 So as not to exceed those of the petitioners by more than 15%. A certain dif ference in prices in favour of local products was allowed in the conditions specified in the invitation-for-offers concerned.

59 A provision to this effect was included in the invitation-for-offers.

60 H.C. 297/82, 37(iii) P.D. 29.

61 For a previous instance see: Z. Segal v. The Minister of the Interior, H.C. 217/80, 34(iv) P.D. 429.

62 35 L.S.I. 124.

63 There were additional arguments.

64 See also S.I. Meizler v. The Local Council of Nesher and another, C.A. 394/82, 37(iv) P.D. 42, where the Berger case is cited in connection with a question regarding the possibility of a public authority's waiver of the free use of any of its powers.

65 Specification of all the detailed facts and their evaluation with regard to the effect of Summer Time on them, as stated in the judgment, would require more space than is available within this survey.

66 Barak J. ended his judgment with what seems to be, with all due respect, an unusual remark in a Supreme Court judgment. He expressed the Court's ex pectation that before the question comes to a renewed decision towards the sum mer of 1983, the Minister will provide himself with the necessary up-to-date data on the relevant subjects. He even added that the fact that the Minister's decision not to introduce Summer Time was reasonable in 1982 does not necessarily lead to the conclusion that a similar decision by him in 1983 will be reasonable as well.

67 The dissenting judgment is even longer than that of the majority.

68 H.C. 486/82, 37(iv) P.D. 780.

69 H.C. 18/82, 38(i) P.D. 701.

69a “Kikar HaMedina” means “The State's Square”.

70 19 L.S.I. 330.

71 The text in the inverted commas is close to what may be termed a free translation from the Hebrew text of the judgment at p. 784.

72 See n. 71 supra.

73 See supra n. 69.

74 The Municipality of Tel Aviv-Jaffa and the Local Council of Ramat HaSharon.

75 The case was pending before the High Court of Justice for about two years.

76 Supra n. 70.

77 Several judgments which deal with licensing issues and with matters of planning and building and which could have been entered under the heading of Local Authorities, have in fact been classified here as pertaining to Administrative Law and the reader is invited to find them there.

78 C.A. 620/82, 37(iv) P.D. 57.

79 1 L.S.I. (N.V.) 247, at 287.

80 It seems that one of the byelaws, i.e. that of 1966 which preceded the relevant one of 1976, was referred to only, or mainly, in order to compare its provisions with those included in the newer one. The observations of the Court with regard to the former byelaw will therefore not be recorded here.

81 Sec. 250 and the relevant part of sec. 251 provide:

“250. A council may make byelaws to enable or assist the municipality in carrying out any of the matters it is required or empowered to do under this Ordinance or any other law, or to require any owner or occupier of property to carry out on such property such work as may be necessary for that purpose. 251. By such byelaws as aforesaid the council may provide—

(1) for the payment of any fees or charges or contribution by any person other than the municipality, in connection with such matters as referred to in sec. 250;

(2) for…”

82 29 L.S.I. 273. Sec. 1(a) provides:

“Taxes, compulsory loans and other compulsory payments shall not be imposed, and their amounts shall not be varied, save by or under Law. The same shall apply with regard to fees.”

83 Apparently the Court meant to convey that the disputed charge is nearer to a fee or contribution than it is to taxes.

84 This term has probably been used to designate property bordering on the streets for the paving of which the charge was imposed.

85 See also Alkayal and another v. The State of Israel, Cr.A. 401/83, at p. 573 infra.

86 H.C. 393/82, 37(iv) P.D. 785. (See also Prof.Dinstein, Y., “The Maintenance of Public Order and Life in the Administered Territories” (1984) 10 Iyunei Mishpat 405).Google Scholar

87 As a result of the Six Day War of 1967.

88 See paragraphs 15 and 16 of the judgment.

89 The word “civil” is in inverted commas in the judgment itself, seemingly in order to stress that it is in contrast to the word “military”.

90 I.e. The Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, 1907, which are annexed to the Fourth Hague Convention of 1907 (see at p. 793 of the judgment).

91 Reference was made to Greenspan, M., The Modern Law of Land Warfare (Berkeley, 1959) 225Google Scholar and H.C. 337/71 Almakadsa v. The Minister of Defence and others, 26 (i) P.D. 574, at 582.

92 See at p. 805 of the judgment. There is also another limitation at p. 806. It states: “…and provided that they will not bring about substantive change in the basic institutions of the region”.

93 This question arose, because the Hague Regulations include provisions only with regard to the confiscation of property for military purposes and do not include provisions with regard to confiscation for the benefit of the local population according to the local law. The positive reply was based on legal literature and on “the accepted attitude” that no negative arrangement with regard to such confisca tion for the benefit of the local population follows from the fact that the Hague Regulations include only provisions for confiscation for military purposes. The Court stated that this attitude is based on the provisions of Regulation 43.

94 H.C. 593/82 (and several more file numbers, all of which were dealt with in the same judgment), 37(iii) P.D. 365.

95 11 L.S.I. 157.

96 And other detainees in the camp of Anzar.

97 Dr.Pictet, J.S. (ed.), Commentary, vol. 4, Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (International Committee of the Red Cross, 1958) 367.Google Scholar

98 p. 375 of the judgment.

99 The judgments in the following cases under the heading of Civil Procedure refer to the Civil Procedure Rules of 1963 (K.T. No. 1477 of 6 August 1963, p. 1853). However it should be mentioned that in 1984 these rules had been abolished and new rules were made (See K.T. No. 4685 of 12 August 1984, p. 2220).

100 C.A. 32/83, 37(iii) P.D. 431.

101 Free translation from the Hebrew text of the judgment at p. 432.

102 I.e. the Court of first instance!

103 The second judgment was given after the case had been referred back to the Magistrate's Court upon an appeal to a District Court.

104 The invitation was posted on the door of the attorney's office and it was also sent to him by registered mail.

105 I.e. the Court which gave judgment in default.

106 See supra n. 99.

107 see also L. Yahalom and others v. The Municipality of Ramat Gan, Leave-to-Appeal 505/83, 37(iv) P.D. 357. Shamgar D.P. dealt therein with the proper use of rule 227 and pointed to the case as an illustration of why the Courts are crammed with litigation which could have been avoided.

108 C.A. 377/81, 37(iv) P.D. 726.

109 2 L.S.I. (N.V.) 41.

110 Leave-to-Appeal 449/83, C.A. 734/83, 38(i) P.D. 613.

111 See supra n. 99.

112 Unfortunately it seems that there is a (printing?) error in the text of the judgment. It seems quite safe to assert that the words “of another” were erroneously set instead of the words “on the spot”. In Hebrew this change can be made by the exchange of one letter in each of the words “of another”.

The above text concerning the Court's remark is close to a translation from the Hebrew text of it, but it is not, and should not be regarded as, a full literal translation. Therefore it has not been put into inverted commas.

113 It seems to me that the topic concerned warrants more detailed separate comment.

114 The exact instructions of the Supreme Court which accompany this holding are omitted from here, and so are several other matters with which the Court dealt in this appeal.

115 Leave-to-Appeal 279/82, 37(ii) P.D. 542.

116 30 L.S.I. 46.

117 Supra n. 95.

118 H.C. 181/81, 37(iii) P.D. 94.

119 However, it was not clarified whether this was done by the husband or by his wife and what exactly happened to this suit. Apparently there was no real hearing in that case.

120 27 L.S.I. 313.

121 Apparently meaning the judgment of October 1980 of the District Court.

122 “Dayanim” is the Hebrew word used to designate members of Rabbinical Courts.

123 16 L.S.I. 106.

124 However, competence to deal with questions of the children's education requires an express request.

125 There is need to examine which of the parents has more suitable characteristics to bring up the children and what are his means for the fulfillment of their basic needs.

126 S.T. 1/81, 38(i) P.D. 365.

127 See Drayton, , The Laws of Palestine, Revised Edition, Vol. III, p. 2569 at 2582.Google Scholar

128 The judgment covers some forty pages of Piskei Din.

129 The reader interested in full particulars will have to seek them in the judgment itself, which also includes references of many judgments and a long list of sources of Jewish Law.

130 See p. 384 bottom, and sec. 25 of the judgment at p. 397.

131 See at p. 409.

132 The main reason being the jurisdiction which the Rabbinical Court had acquired earlier in this case.

133 From the number of the case—1/81—it follows, that it was filed in 1981. Judgment was delivered in February 1984.

134 H.C. 256/83, S.P. 552/83, 37(iii) P.D. 273.

135 See D. Reich v. A. Reich, H.C. 80/79, Motion 344/79, 33(ii) P.D. 589. From this earlier case we learn, among others, that the litigants are Jews and were citizens of the United States of America, where they had their residence and where their children were born. That case resulted in the respondent's agreeing to return the litigants' child, Yitzhak, to his mother, and judgment was given to this effect.

136 See supra n. 135.

136a See supra n. 134.

137 7 L.S.I. 139.

138 Section 3 of the Rabbinical Courts Jurisdiction (Marriage and Divorce) Law, 5713–1953 provides:

“3. Where a suit for divorce between Jews has been filed in a rabbinical court, whether by the wife or by the husband, a rabbinical court shall have exclusive jurisdiction in any matter connected with such suit including maintenance for the wife and for the children of the couple”:

139 Section 9 provides:

“9. In matters of personal status of Jews, as specified in article 51 of the Palestine Orders in Council, 1922 to 1947, or in the Succession Ordinance in which a rabbinical court has not exclusive jurisdiction under this Law, a rabbinical court shall have jurisdiction after all parties concerned have expressed their consent thereto.”

140 The Court also dealt with additional topics raised by the respondent in support of his contentions.

141 H.C. 7/83, 38(i) P.D. 673.

142 Instead of the three required by sec. 8(e) of the Dayanim Law, 5715–1955 (9 L.S.I. 74). (See: Dr.Shochetman, E., “Rabbinic Court Judgments Entered by a Panel Lacking a Quorum or Based on Incorrect Legal Analysis Concerning the Welfare of the Child—Are they a Basis for Intervention by the High Court of Justice?” (1985) 15 Mishpatim 287.Google Scholar)

143 It should be noted that this was not what the father had requested. He had asked to transfer the children to an institution.

144 It is not clear from the judgment why the Court stated that the notice was given to the mother and not to both litigating parents.

145 The exact nature of these requests is not disclosed.

146 11 L.S.I. 157.

147 16 L.S.I. 106.

148 See supra at p. 521.

149 See supra at p. 524.

150 See supra n. 142.

151 The Judge cited from 1 Halsbury, , The Laws of England (London, 4th ed., by Hailsham, Lord, 1973)Google Scholar and referred to additional sources.

152 See also the case of G. Sha'ar v. The Regional Rabbinical Court of Tel Aviv, H.C. 378/83, 38(i) P.D. 778 where the High Court dismissed a petition filed before appeal to the Rabbinical Grand Court and differentiated this case from Biaras in that there the Court regarded its intervention as urgent in order to prevent imminent results, whereas the facts of the Sha'ar case did not warrant a similar reaction.

153 I.e., the part regarding the abolishment of the decision of the Rabbinical Court.

154 I.e., the part requiring the Rabbinical Court to state the reasons for its decision.

155 H.C. 546/81, 37(iii) P.D. 332.

156 7 L.S.I. 139.

157 Petition for leave to appeal 258/81, C.A. 488/81 and C.A. 508/81, 37(iii) P.D. 645.

158 However, from the remarks of D. Levine J. in the Supreme Court, it follows that the lower Court Judge did not restrict the order's duration because he thought that such an order is in any case not final.

159 The Judge did not state any reason for the different expiry date which he named.

160 C.A. 442/83, 38(i) P.D. 767.

161 C.A. 577/83, 38(i) P.O. 461. “Plonit” means a female anonymous and in this case stands in lieu of the name of the biological mother of the child concerned so as not to disclose her identity and that of her child.

162 It is stated in the judgment that the biological mother was at the time a young unmarried student, and that the child's father was a much older man, married and a father of six. At the time the mother consented to the adoption of the child, her parents were not willing to support her. But later their attitude changed, the young mother completed her studies and started to work and she wanted to revoke her consent for the child's adoption.

163 Free translation from the Hebrew text.

164 35 L.S.I. 360.

165 This survey does not include judgments of the National and Regional Labour Courts.

166 C.A. 683, 684/80, 37(iv) P.D. 16.

167 26 L.S.T. 77 at 83.

168 2 L.S.I. (N.V.) 5.

169 11 L.S.I. 51.

170 23 L.S.I. 76.

171 See Judgments of Labour Courts, P.D.A. Vol. 3, p. 253.

172 11 L.S.I. 157.

173 F.H. 17/82, 38(i) P.D. 289.

174 H.C. 338/83, 37 (iv) P.D. 645.

175 22 L.S.I. 114 at p. 125.

176 See at p. 648 of the judgment.

177 It should be noted that the heart attack occurred in October 1976, that the case came before the High Court of Justice only in 1983, and that that Court delivered its judgment in December of that year. However, this was not the end of the litigation. As stated above the case was referred back to the National Labour Court, with the probability that from there it will be returned to the court of first instance—i.e. the Regional Labour Court.

178 H.C. 676/82, 37(iv) P.D. 105.

179 C.A. 15/83, 37(iv) P.D. 267.

180 The judgment deals with a variety of subjects in connection with the contract concerned but in this survey only the subject of the deletion and the legal questions related to it will be taken up.

181 25 L.S.I. 11.

182 27 L.S.I. 117, at p. 121.

183 See also C.A. 130/83, L. Preiss and others v. E. Preiss, 38(i) P.D. 721, where the Court stated, referring to the case of Beiers (C.A. 15/83) that it is a rule that when the text is unequivocal no recourse is to be made for the purpose of its interpretation to erasures made in a previous text.

184 C.A. 464/81, 37(iii) P.D. 393.

185 Although Bach J. referred to this case in Jacob Co. (Israel) Ltd., v. The Company for the Development of Eilat Ltd., C.A. 283/81, 37(iii) P.D. 658.

186 The exact provisions of the contract concerned need not be specified here, since the main legal issues in this case can be explained without them.

187 27 L.S.I. 117.

188 In any case not without first granting the appellant a reasonable extension of time for the performance of the contract.

189 C.A. 76/81, 37(iii) P.D. 622.

190 M. Landau was the President of the Supreme Court at that time.

191 I.e. non-eviction despite a cause for eviction. See sec. 132 of tKe Tenant's Protection Law (Consolidated Version), 5732–1972 (26 L.S.I. 204). Sec. 132(a) provides:

“Notwithstanding the existence of a ground for eviction, the Court may refuse to give judgment for eviction if it is satisfied that in the circumstances of the case it would not be just so to do.”

192 The emphasis on making the decision according to the circumstances at the time of the decision (and not at the time close to the filing of the suit or earlier) appears to warrant special attention.

193 I.e. the decree which gave the agreement between the parties the force of a judgment.

194 C.A. 789/82, 37(iv) P.D. 565.

195 15 L.S.I. 215.

196 26 L.S.I. 204.

197 C.A. 141/63, 17 P.D. 2957.

198 C.A. 748 and 798/80, 38(i) P.D. 309.

199 However, registration of the transfer was carried out with only a relatively short delay.

200 25 L.S.I. 11.

201 “Seemingly” — because, on the one hand, Avnor J. stated so (at p. 314 of her judgment), but, on the other, she also stated (at the following page) that to her mind the (District) Court rightly held that there was a breach “as aforesaid”.

202 This fact may indicate that the District Court was indeed of the opinion that the seller was in breach of the contract.

203 Here is the wording of the headline to sec. 18 and of sec. 18(a):

“Exemption by reason of constraint or frustration of contract.

18. (a) Where the breach of contract is the result of circumstances which at the time of making the contract the person in breach did not know of or foresee and need not have known of or foreseen, and which he could not have avoided, and performance of the contract under these circumstances is impossible or funda mentally different from what was agreed between the parties, the breach shall not give cause for enforcement of the contract or for compensation.”

204 Probably in the sense of not officially registering the transfer.

205 As distinct from non-transfer.

206 Conditioned by a certain payment to him.

207 The judgment does not state the exact nature of the offered document, but apparently it was meant to enable the purchaser to use it for the registration of the land in the name of the purchasing company without need of further recourse to the seller and thus to assure the purchaser's rights to the land.

208 This attitude was disputed by Prof.Weisman, J., “Irrevocable Power as Sub stitute for Sale of Land” (1985) 14 Mishpatim 572.Google Scholar

209 C.A. 213/80, 37(iii) P.D. 808.

210 I.e. the parts which caused the litigation on the question to whom they belong.

211 27 L.S.I. 213.

212 Sec. 8 was included in the contract and not attached to it. The Court explained that the aim of the said Law is to bring to the purchaser's knowledge in a clear and undisguised manner the seller's true intentions and the rights that the pur chaser acquires from him.

213 Because it was made later than the contract.

214 In the sense of an owner of a flat.

214a 23 L.S.I. 283.

215 The correctness of this holding was disputed by Prof.Weisman, J., “Allocation of Common Parts in a Condominium to Individual Unit Owners”, (1984) 10 Iyunei Mishpat 611.Google Scholar

216 C.A. 753/82, 37(iv) P.D. 626.

217 26 L.S.I. 204, at p. 213.

218 C.A. 288/71, 26(i) P.D. 393.

219 H.C. 323/81, J. Vilosni v. The Rabbinical Grand Court in Jerusalem, 36(ii) P.D. 733.

220 ![]() — See at p. 632.

— See at p. 632.

221 I have added the words in brackets that are not included in the Court's summing up at p. 632, since their addition seems to help clarify the Court's intention, as expressed in other parts of the judgment.

222 The consenting judgment of Elon J. includes a hint that the ruling in this case might not apply to instances where a spouse left the jointly occupied flat voluntarily.

223 H.C. 305/82, 353/82, 38(i) P.D. 141.

224 It should be noted that the issue concerned joint ownership of land and not co-ownership of a cooperative house.

225 Planning and Building Regulations (request for permit, its conditions and fees) (amendment No. 3), 5737–1976, K.T. 1976/77, p. 534.

226 In this context sec. 30(c) of the Land Law, 5729–1969 (23 L.S.I. 283 at 287–8) was mentioned, according to which the consent of all joint owners of the land concerned is required for “any matter outside the scope of ordinary management and use”.

227 It remains now for the Knesset, in its legislative capacity, to examine whether in deed that result matches its intention when it enacted the Land Law (and for the Executive to examine this result in view of the Regulations concerned), or whether the Court's holding requires a change in the Law (or in the Regulations). Reconsideration of the matter by the Legislature and the Executive seems to be important not only for the benefit of potentially aggrieved joint owners in land, who—in view of this judgment—will have to “fight” for the preservation of their rights in courts, but also for the benefit of the public at large, in whose interest it is that the courts, which are already overburdened, will not be subjected to this kind of litigation also.

228 Seemingly to enable the opposing joint owners to apply to the courts. It should, however, be noted that the period of 30 days apparently starts from the day on which the Committee received the application and not on the day on which the joint owner, or owners, were served with a copy of it, which supposedly will as a rule be a later day. Thus the period left for aggreived joint owners to apply to the courts will usually be shorter than 30 days.

229 in a previous part of the judgment the Court stated that it had been established that after certain alterations, the application for the permit and the plans attached to it conformed with the Local Committee's requirements, but for the lack of consent of the joint owners.

230 C.A. 84/80 and C.A. 89/80, 37(iii) P.D. 60.

231 C.A. 89/80.

232 19 L.S.I. 231. Sec. 10(a) provides:

“Any property which comes into the possession of the agent in consequence of the agency is held by him as a trustee of the principal. This applies even if the agent has not disclosed the existence of the agency or the identity of the principal to the third party.”

233 23 L.S.I. 283.

234 Because of an injunction issued at the request of the first respondent.

235 The judgment also includes directions with regard to the payments which Dr. Nadim Kassem owes to Camal Kassem for what the latter had paid for the acquisition of the house.

236 F.H. 24/81, 38(i) P.D. 413.

237 C.A. 619–621/78, 35(iv) P.D. 281.

238 Against the dissenting opinion of Ben Porat J.

239 C.A. 619–621/78 and F.H. 24/81 together extend over more than fifty pages of Piskei Din.

240 2 L.S.I. (N.V.) 5 at pp. 23 and 24.

241 Seemingly this term was meant to refer to the monetary resources of the kibbutz.

242 Despite the fact that in a sense the members of a kibbutz can be regarded as constituting one large family.

243 See at p. 426 of the judgment.

244 17 L.S.I. 64.

245 C.A. 862/80, 37(iii) P.D. 757.

246 1 L.S.I. (New Version) 247, at p. 280.

247 In the sense of a public authority with governing powers, meaning the appellant Municipality in this case.

248 This term has already been used and explained in the case of S. Va'aknin v. The Local Council of Bet-Shemesh and another, C.A. 145/80, 37(i) P.D. 113. See supra n. 2 at 567–569.

249 C.A. 326/81, 38(i) P.D. 745. The judgment was delivered on 26 March 1984.

250 i.e. the first respondent in the appeal who was liable for the accident.

251 2 L.S.I. (New Version) 5 at pp. 24–25.

252 The relevant parts of sec. 82 provide:

“82(a) A person insured under Part Two of the National Insurance Law, 5714–1953 …, including a dependant of such person… who is entitled under this Ordinance, in consequence of one event, both to compensation from the employer and to a benefit under Part Two of the Law shall have the amount of the benefit deducted from the amount of compensation which would be due to him from his employer but for this section.

(b) For the purposes of this section — ‘benefit’ means the monetary value of a benefit, … and … a benefit reduced or denied in consequence of any act or omission on the part of the employee… shall be deemed to have been given or to be due to be given in full; …” (2 L.S.I. (N.V.) at p. 24).

253 ![]()

254 I.c. if he had paid the insurance fees pertaining to his work as a self-employed person.

255 C.A. 750/79, 37(iv) P.D. 449. Judgment was delivered on 20 November 1983. No explanation is given in the judgment as to the reason for the delay. It should be noted, that the accident occurred before the Road Accident Victims Compensation Law, 5735–1975 (29 L.S.I. 311) was enacted.

256 They thought that local principles and standards had been applied and that only in calculating the loss the lower Court took into account the fact that the real loss of earnings crystallized in the United States.

257 The judge added that this is so in England and in the U.S. “despite the difference between the two systems”.

258 See at pp. 460 and 461 of the judgment.

259 The judgment goes into certain, but not full, details of the calculation.

260 Shilo J. dissented from this holding because American Dollars are not legal tender in Israel. This subject warrants to my mind a detailed separate note.

261 it seems that even the Supreme Court found it difficult to decide this case. Although the appeal was dismissed, it seems that signs of hesitation can be spotted in the judgment, and it is not easy—if at all possible—to draw from it clear cut rules. Perhaps the guideline of the judgment is the Court's opinion that the range of possibilities should be wide while examining, in any given case, which is the proper Law (sec at pp. 459 and 465 of the judgment).

262 C.A. 865/80, 37(iii) P.D. 326.

263 17 L.S.I. 193.

264 The appellant demanded the tax for two transactions, whereas the respondent contended that there was only one transaction, namely, that in which the company was the buyer.

265 19 L.S.I. 231 at p. 232.

266 The English case of Kelner v. Baxter and others (1866) 2 C.P. 174 was mentioned in this context.

267 C.A. 738/80, 37(iv) P.D. 387.

268 Seemingly meaning in addition to the price stipulated in the contract for the property.

269 This is a phrase commonly used to refer to the official registration of the transfer of land to its buyer.

270 Cr. A. 115/82, 168/82, 38(i) P.D. 197. (The judgment covers over 60 pages of Piskei Din.)

271 free translation from sec. 49 at p. 225 of the judgment.

272 L.S.I. Special Volume, Penal Law, at p. 74.

273 2 L.S.I. (N.V.) 198 at p. 200. Of course the other Judges on the Bench also referred to this section.

274 ![]()

275 C.A. 635/80 and 520/80, 38(i) P.D. 85.

276 21 L.S.I. 149.

277 ibid., at 163.

278 The turning to explanatory notes of Bills for the interpretation of the Law enacted, while not unprecedented, is rather an unusual practice.

279 Bochan, Insurance Co. Ltd., Haifa v. B. Rosenzweig, F.H. 13/67, 22(i) P.D. 569.

280 A petition for a Further Hearing was rejected: P. Rosenberg and another v. R. Rubinstein and another, F.H. 2/84, 38(iii) P.D. 689.

281 C.A. 483/80, 37(iii) P.D. 552.

282 K.M. No. 1793 of 1965, p. 228. These Regulations have been amended several times.

283 Cr.A. 532/82, 37(iii) P.D. 243.

284 The appellant in this case was convicted by a lower Court for an offence against sec. 356 of the Penal Law, 5737–1977 (an indecent act committed upon a minor).

285 Cr.A. 433/77, 32(i) P.D. 548.

286 9 L.S.I. 102, at p. 104.

287 See also: Petition for leave to appeal 78/84, J. Tatroashvili v. The State of Israel, 38(i) P.D. 659, where a similar question was raised with regard to the admissibility of evidence of a youth interrogator on his impression of the reliability of a minor who made a statement before him. Shamgar P. stated that there exist two attitudes (of the Supreme Court) regarding the admissibility of such impressions, but he saw no need to rule on that point in this case.

288 C.A. 716/81, 37(iv) P.D. 132.

289 I.e. the agreement to indemnify the husband.

290 Cr.A. 401/83, 38(i) P.D. 354.

291 They were detained while still within the territorial waters of Jordan.

292 3 L.S.I. (N.V.) 5.

293 L.S.I. (Special Volume) — Penal Law, 5737–1977.

294 3 L.S.I. (N. V.) 5 at p. 13.

295 The plural is used in the text of the judgment.

296 There is no reference to which specific “relevant conventions” the Court referred.

297 I.e. the single convention regarding narcotic drugs of 30 March 1961.

298 S.P. 11/83, 38(i) P.D. 6.

299 S.P. 728/83, 37(iii) P.D. 515.

300 Cr. A. 204/83, 37(iv) P.D. 589.

301 The Court mentioned that it was stated in the decision regarding postponement of the punishment that as a rule, when a request concerns imprisonment for a long period it should not be allowed, but it found this case to be outstanding mainly because of the complicated relationship between the complainant and her family and the accused, and also because of the recommendation of the Probation Service.

302 Cr.A. 593/83, 37(iv) P.D. 614.

303 Most probably the Court meant “the accused”.

304 Cr.A. 10/84, 38(i) P.D. 190.

305 Cr.A. 793/83, 38(i) P.D. 363.

306 36 L.S.I. 35, at p. 61.

307 Sh. Cohen v. The State of Israel, Cr.A. 292/82, 36(iv) P.D. 729.

308 Permission to Appeal 152/84, 38(i) P.D. 839.

309 Regrettably, and apparently owing to some printing errors in the decision as published in Piskei Din, the list seems to be incomplete.

310 The decision does not state how close to the end of the period of imprisonment the respondent was.

311 See for instance Cr.A. 705/81, 36(iv) P.D. 223 included in the previous survey cited supra n. 2 at 593.