No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 February 2016

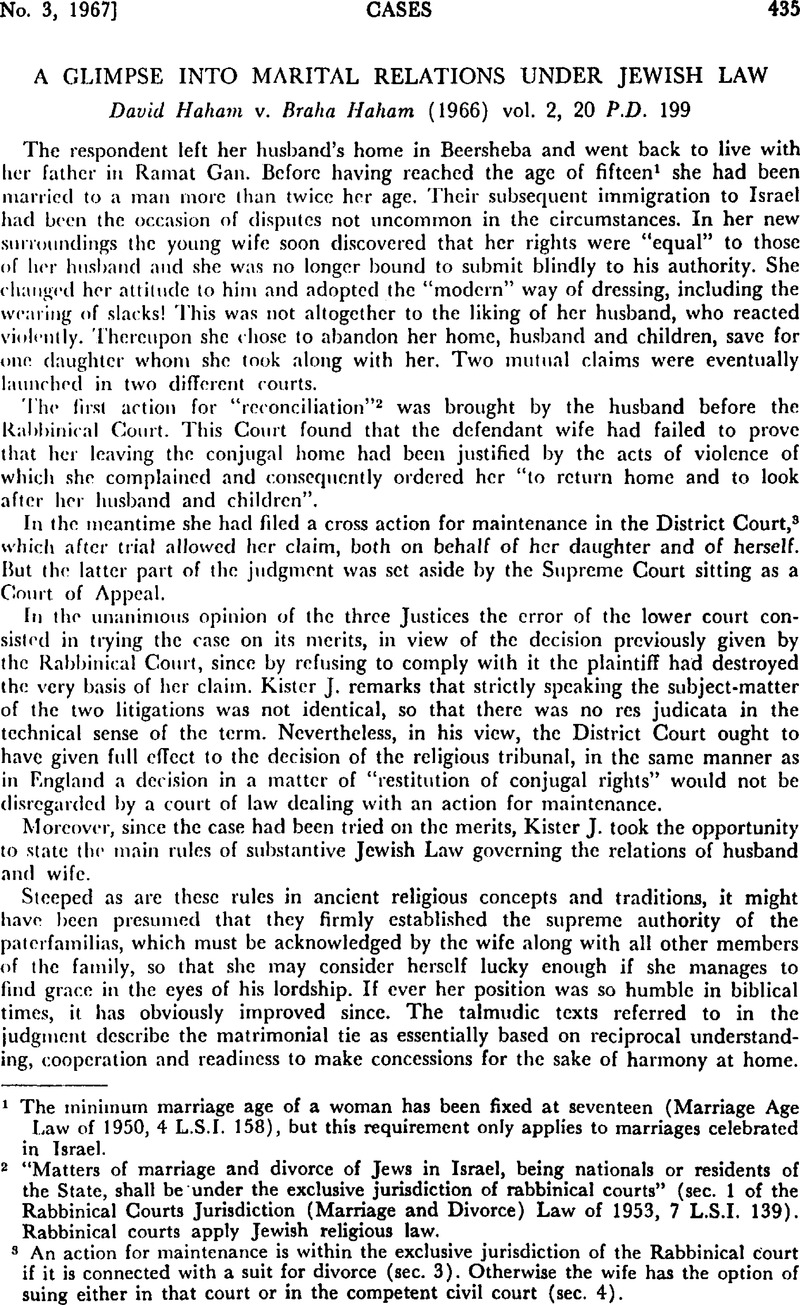

1 The minimum marriage age of a woman has been fixed at seventeen (Marriage Age Law of 1950, 4 L.S.I. 158), but this requirement only applies to marriages celebrated in Israel.

2 “Matters of marriage and divorce of Jews in Israel, being nationals or residents of the State, shall be under the exclusive jurisdiction of rabbinical courts” (sec. 1 of the Rabbinical Courts Jurisdiction (Marriage and Divorce) Law of 1953, 7 L.S.I. 139). Rabbinical courts apply Jewish religious law.

3 An action for maintenance is within the exclusive jurisdiction of the Rabbinical court if it is connected with a suit for divorce (sec. 3). Otherwise the wife has the option of suing either in that court or in the competent civil court (sec. 4).

4 Mishne Torah, Book 4 (Nashim), Treatise 1 (Hilkhot Ishut) c. 15, §§ 19–20.

5 During the early years of the British Mandate, orders of religious courts directing wives to return to their husbands were enforced by Execution Officers of the civil courts “through the instrumentality of the Police”. The validity of this practice was challenged and eventually denied by the Supreme Court in 1933 (Barhum v. Chief Execution Officer & Izimr (1934) 2 P.L.R. 40Google Scholar). According to that decision, execution proceedings merely consist in a warning to comply with the judgment, “and the person adjudged against, if a wife, loses her right to alimony” (at p. 41). It will be noted that in the Barhum case the order had been given by the Latin Ecclesiastical Court of Jerusalem. A similar view had been adopted in 1879 by the Chief Execution Officer in Constantinople, in the following terms: “The constitution and continuation of matrimony is based on mutual consent. Judgments calling for obedience in their essence and spirit consist of a Sharia warning to secure their aim, their legal consequence being to put an end to the obligation of the husband to support his wife in case of non-obedience. It is considered by me proper to act accordingly; but it has been the practice hitherto to execute such judgments by way of sending the wives to the houses of their husbands by force. As the husband has no legal or Sharia right to keep his wife imprisoned in his house, to leave the wife in the house of her husband would mean going back to the epoch of slavery and it is therefore impossible. On the other hand to restrict execution to one occasion (meaning, just to bring the wife to the house without forcing her to remain there) would not secure the object, and, moreover, as such procedure would amount to arbitrary and compulsory measures which brought no result, it is very questionable whether such procedure would even be in accordance with Sharia Law.”

6 This solution coincides with that of Sharia (i.e. Moslem religious) law, cf. preceding note.