Introduction

The role of divine sanctuaries in ancient Mesopotamian healing beliefs is a central, albeit troublesome question.Footnote 1 While previous research has shown that some temples of the healing goddess Gula held a role in connection to sufferers’ pleas for recovery, it is still unclear if these individual observations can be used to outline a general hypothesis regarding the function of Gula’s temples. Furthermore, the role of private sanctuaries remains largely unexplored.Footnote 2 The only systematic treatment of the topic remains the study by Hector Avalos (Reference Avalos1995).Footnote 3 One reason why this question has been largely avoided is that the purely medical prescriptions, diagnostic manuscripts, ritual instructions, and pharmacological texts, found on cuneiform tablets from especially the second and first millennia B.C.E., rarely mention temples (e.g., Arbøll Reference Arbøll2021: 187–188). Therefore, relevant information must be extracted, and patched together, from a variety of other sources, such as literary and epistolary texts. Another problem is that the primary healers, the asû and āšipu/mašmaššu,Footnote 4 inadequately translated as “physician” and “exorcist”, were not temple personnel in the second millennium B.C.E. In the Neo-Assyrian period, the āšipu became connected to temples where he performed some rituals, though he was not a priest,Footnote 5 and in the second half of the first millennium B.C.E. the asû disappears from the records, and the āšipu becomes one of the primary professions connected to temples (Steinert Reference Steinert2018a: 190 n. 168 with references). In texts related to these professions, a few references instruct a patient to seek out the sanctuary of a deity. However, the exact purpose of such phrases in healing texts remains unclear (see Geller Reference Geller1998: 133; Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 368; Seux Reference Seux1966; Stol 1991–92: 57).

This article collects and discusses the limited number of medical prescriptions instructing a patient to seek out the sanctuary of a deity in connection to healing to expand our understanding of the role sanctuaries held in the healing process. Such phrases are solely found in manuscripts concerning diseases of the ears and the spleen/pancreas (ṭulīmu). With the recent discovery of a new variant of such phrases, in a medical manuscript from Hama (ancient Hamath) in Syria, this paper re-evaluates the information supplied by these phrases in a healing context. On the basis of text editions of the relevant symptom descriptions in Appendix 1, the following sections analyse the meaning of the relevant words and phrases, related phrases in terrestrial omens, the role of the ears in Mesopotamian medicine, why gaining a good fortune for specific days was relevant for the patient, and the context of the relevant manuscripts. Finally, a conclusion is offered.

Seeking out sanctuaries in connection to healing

In the hundreds of medical manuscripts available to us today, only a few handfuls of therapeutic texts mention the patient visiting a temple. I have been able to identify references to seeking out the sanctuary of a deity in 12 medical prescriptions found on six manuscripts of six distinct cuneiform tablets, all dated to the 1st millennium B.C.E. (Appendix 1). These relatively few examples specify in their symptom descriptions that the patient should seek out (kin, kin.kin; G-stem and Gtn-stem of šeʾû) the sanctuary (ašru/aširtu) of a specific deity (Sîn, Ninurta, Šamaš, Ištar, Marduk) in order to achieve good luck or divine favour (sig 5, dumqu/damiqtu), occasionally specified to last for a number of days or occurring on a specific day. This section examines the relevant manuscripts by analysing the terminology employed and discussing the general evidence for seeking out temples in connection to healing.

Of the six manuscripts with prescriptions relevant for this article, the first is a 9th century B.C.E. medical compendium from Hama in Babylonian script consisting of four fragments, which cannot be joined directly (Arbøll Reference Arbøll2023: 156–165). The contents all concern problems in the ears, ranging from pains and stings to pus leaking from the inner ear, and the manuscript contains prescriptions directed at treating these ailments. Where the first three fragments all contain the remains of longer symptom descriptions and prescriptions, the fragment from the reverse preserves mainly one or two-lined prescriptions. The manuscript preserves roughly 10 legible entries.

The second and third manuscripts are BAM 503+ (Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 367–387) and the duplicate(?) K.15236, two 7th century B.C.E. Nineveh medical manuscripts in Neo-Assyrian script, with a host of symptom descriptions, prescriptions, and incantations for treating disorders of the ears. It is possible that BAM 503+ represents the only tablet related to the ears in the medical series šumma amēlu muḫḫašu umma ukāl (Heeßel Reference Heeßel2010a: 31–35; Steinert Reference Steinert2018b: 223; Steinert et al. Reference Steinert, Panayotov, Geller, Schmidtchen and Johnson2018: 210 lines 11-12). Several entries are partially similar to those found in the Hama manuscript, though there are differences indicating that the texts were part of different traditions. The fourth and fragmentary Late Babylonian manuscript BM 41289+, a two-columned library tablet from Babylon, duplicates some of the prescriptions in BAM 503+.

The final two manuscripts are the two duplicates BAM 77 and 78 from Neo-Assyrian Assur and in Neo-Assyrian script, one of which is an extract manuscript produced by the famous exorcist Kiṣir-Aššur.Footnote 6 They both contain symptom descriptions and prescriptions for treating disorders of the ṭulīmu (spleen/pancreas). These manuscripts differ slightly from the preceding, in the sense that they concern different disorders.

Moving into a discussion of the terminology employed, the three central terms discussed in this section are: (1) a word before the divine name, which has been interpreted as a form of ašru “place” with the resulting meaning “sacred place, shrine” in relation to gods or the word aširtu “temple, sanctuary, special room” as well as “cult socle”; (2) the verb šeʾû “to look for, seek out” with derived meanings; and (3) the idiomatic phrase dumqu/damiqtu amāru literally “to see good fortune.”

(1) The word for the place that was sought out in these prescriptions was a form of ašru or the term aširtu in the construct state before a divine name. The CAD (A/2: 458–459) lists the form aš-rat as ašru “place, site, location, sacred place, cosmic locality” referring to the “shrine” of a deity,Footnote 7 though in order to get the construct form aš-rat from this noun, the form should likely be interpreted as the plural ašrātu (see, e.g., CAD Š/2: 362; Freedman Reference Freedman1998: 168–169). Seux (Reference Seux1966: 172, 174) interpreted aš-rat as a plural of ašru “place” and stated, on the basis of several examples outside the medical corpus of this word with the Gtn-stem of šeʾû, that this phrase “peut désigner le processus qui aboutit à l’obtention d’un oracle.”Footnote 8 While individual examples outside the medical corpus may represent a plural of ašru,Footnote 9 it is not certain that this was the case in the medical texts. The noun aširtu (listed as ešertu I in the CDA: 82, aširtu I in the AHw: 90, and aširtu in the CAD A/2: 436–439) could be written aširtu in Standard Babylonian and Neo-Assyrian contexts, although it is most frequently attested as ešertu or iširtu. The term could have a variety of meanings, and it could designate almost any place of worship.Footnote 10 The examples from the dictionaries show that an aširtu could be located in an official temple as well as in a private home, and the CAD (A/2: 438) demonstrates that the word could describe a special room or altar in a private house. If we follow this reading in medical contexts, it is possible that patients were encouraged to seek out an official temple in the city, a local chapel, or a sanctuary in their own homes.Footnote 11 The exact meaning of the word in these contexts is unclear, though it seems to refer to a place where divine favour could be sought out.Footnote 12 The uncertainties regarding a precise physical location related to the word may indicate that the prescriptions did not necessitate that a patient had to visit an official temple institution. Instead, it seems reasonable to assume the divine favour could be acquired by visiting a local, or even private, shrine.

Even if any general role of Mesopotamian temples in healing is far from clear, there is strong evidence to suggest that the healing goddess Gula’s temples held some function in connection to recovery (Avalos Reference Avalos1995: 201–203, 209–222; Böck Reference Böck2014: 58, 114–115; Robson Reference Robson2008: 465; cf. Geller Reference Geller1998: 132–133). The data originates mainly from her temple in Isin, but it indicates that her places of worship in general may have been visited for curative purposes. For example, offerings were also made to Gula in her temple in Assur for the healing of a princess (Sibbing-Plantholt Reference Sibbing-Plantholt2022: 74). This temple even included a large medical library (see Arbøll Reference Arbøll2021: 255–256 with references). Gula’s animal was the dog, and such animals were kept in several of her temples, possibly due to certain curative aspects associated with them.Footnote 13 Furthermore, it is clear that a patient – or someone acting on this person’s behalf – could petition Gula in her temple in connection to suffering, and the remains of votive figurines in her temple in Isin may originate from acts of supplication (Böck Reference Böck2014: 114–115 and n. 58 with additional references). Circumstantial evidence, such as the comical tale of Ninurta-pāqidāt’s dogbite, could indicate that some temple personnel held a role in healing in the first millennium B.C.E.Footnote 14 Still, the patient’s house was the ordinary venue for healing ceremonies (e.g., Arbøll Reference Arbøll2021: 129), and it cannot be excluded that the few references in medical texts to seeking out deities refer to local or domestic sanctuaries or altars. Especially when considering that many people likely experienced restricted access to most parts of a temple in the first millennium B.C.E.Footnote 15 Furthermore, the association of Gula, and her temple, with the city Isin may confuse the evidence, seeing as Isin itself was known in various periods as the centre of the healing art asûtu, the craft of the asû-physician.Footnote 16

(2) The verb šeʾû in the medical prescriptions treated here was written either kin or kin.kin, of which the former likely represents a G-stem and the latter a Gtn-stem. The Gtn-stem can mean “to look all over, everywhere for, to seek for a purpose” as well as “to be assiduous (in reverence) toward, to be solicitous (for the welfare of)” (CAD Š/2: 355–363), the latter particularly attested with places.Footnote 17 The AHw (1223) provides the reading “aufsuchen”, while the CDA (369) translates the verb “to ‘visit’ places ‘assiduously’” (see also Frazer Reference Frazer2015), which resonates with translations such as “persistently seeking” (Freedman Reference Freedman1998: 168–169 line 155). The action of seeking a shrine of a deity in relation to healing appears to be a well-established response to illness, as exemplified by a šuʾilla-prayer to Marduk stating: “Always let me seek the shrine of he[al]th. Thus, they (humankind) were commanded always to bear curses by the gods, the hand of the gods is for men to bear.”Footnote 18 Even Enlil is described as constantly seeking out Gula for “incomparable decrees.”Footnote 19

(3) The phrase sig 5 igi-(mar) “to experience good fortune” can be read dumqu amāru or damiqtu amāru. The two possible readings of sig 5 are both related to the verb damāqu “to improve, prosper”, which is also used in a few cases in healing texts instead of balāṭu (e.g., Arbøll Reference Arbøll2021: 330). The second element is the verb “to see, behold, experience.” The term dumqu can mean “good luck, good fortune, favour, (divine) grace, prosperity” in the CAD (D: 180-183), AHw (176) provides “Gutes, guter Zustand, gutes Aussehen, Wohltat, gute Bedeutung”, and CDA (62) builds on the AHw and translates “good (thing), welfare, good condition, favourable, good results.” The word damiqtu is translated with almost identical nuances as “favour, good will, luck” in the CAD (D: 64–67) and “good fortune” in the CDA (55), although the AHw (157) prefers a more general translation.Footnote 20 There is in essence so little difference between the nuances encapsulated in the two words that the reading of the Sumerogram sig 5 is without consequences for its meaning. Marten Stol (1991–92: 57) interpreted the phrase as damiqta immar, which he translated as “experience nice things.” Building on the argument by Seux (Reference Seux1966: 173), discussed above, Stol regarded it as a reference to the “expected result of the extispicy” and an equivalent to the resulting phrase “he will live” (balāṭu), frequently found in medical prescriptions. Though the bārû-diviner played a role in confirming a diagnosis, providing a prognosis, or determining whether a cure should be provided (see Heeßel Reference Heeßel, van Buylaere, Luukko, Schwemer and Mertens-Wagschal2018), extispicy and other dealings of the bārû did not occur in a temple context.Footnote 21 But this was not necessarily what was meant in the examples cited by Seux (Reference Seux1966: 172–174), which could also refer to oracles experienced in temples.Footnote 22 In terms of the phrase acting as a substitute for “he will live”, the prescriptions stating that the patient should seek out a sanctuary could also specify separately that the patient will live (e.g., BAM 503+ col. iii 72’–74’, see Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 385), and it appears that the phrase had a different function, not least because it was part of the symptom description before the cure itself.

The reading of sig 5 as dumqu is preferred in this paper, although it is unclear if the phrases held an inherent wish for physical wellness in connection to appearance, as the use of dumqu to designate “beauty” could hint at the physiognomic capacity of the word.Footnote 23 Regardless, good luck and fortune obviously held some connection to omens, which is clear from the examples cited under dumqu in the CAD. It is well known that omens were vital in connection to providing a diagnosis and prognosis, as exemplified by the first subseries of Sa-gig (see Arbøll Reference Arbøll2021: 146–147 with references). Thus, if a patient sought out encouraging omens or divine favour in connection to healing, it might have created the best possible circumstances for a positive prognosis.

In JoAnn Scurlock’s opinion, the patient took advantage of a medical condition to gain good luck via sanctuaries (Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 368). Although the texts occasionally vary the phrases, the gist is that by seeking out an aširtu the patient was provided with favourable conditions.Footnote 24 Perhaps the fortune was meant to counteract the symptoms. Or more likely, the fortune was related to the cure itself. Regardless of the nuances we read into these phrases, the question remains how common the practice of seeking out temples in connection to healing actually was.

Finally, two prescriptions advising a patient to seek out the sanctuary of Marduk do not specify that the patient will experience positive favour. BAM 77 and 78 state that the patient will be well (balāṭu) when seeking out this sanctuary. As emphasized elsewhere by Geller (Reference Geller1998: 133), statements referring to seeking out temples should be taken literally, because it is possible that incantations or rituals were then performed in the sanctuary of Marduk. Whether this was the cases is unclear. While it is uncertain in most instances why the sanctuaries of particular gods were chosen, a Late Babylonian medical commentary explains why Marduk’s temple was auspicious for healing ailments of the spleen/pancreas (ṭulīmu): “‘If a man’s ṭulīmu hurts him, he should visit the temple of Marduk assiduously and he will live’, is because šà.gig means ‘Jupiter’ (the planet of Marduk) and šà.gig means ṭulīmu.”Footnote 25

Related references from Šumma ālu

Six omens with phrases partially similar to the instructions discussed above are found in the divinatory corpus.Footnote 26 Generally, medical symptoms were considered signs of the body, and an ongoing debate concerns whether the diagnostic-prognostic statements in the series Sa-gig should be classified as omen literature or considered separately (e.g., Heeßel Reference Heeßel2000: 4–5; cf. Koch unpublished: 12–14). Furthermore, omens from Šumma ālu were included in the second tablet of Sa-gig (Reference HeeßelHeeßel 2001-02: 24-26). It is therefore necessary to review the six examples to consider if they were related to the material under investigation.

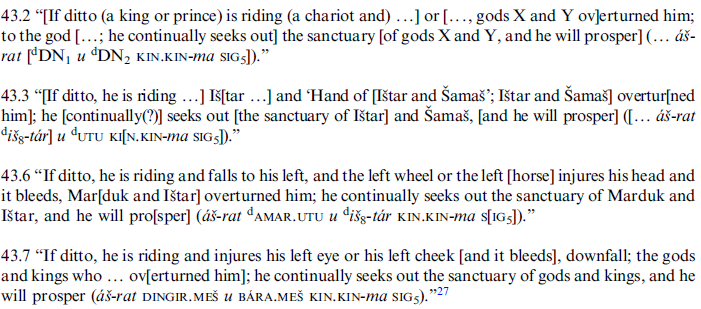

Four chariot omens mention injuries of the head, eye, and cheek in tablet 43 of Šumma ālu, and they recommend seeking out the sanctuaries of Ištar, Šamaš, and Marduk (cited according to the edition by Freedman Reference Freedman2017: 26 with slight modifications in the final phrases):

Unlike the medical prescriptions, the final sign must be interpreted as the verb damāqu in these omens. The translation by Freedman (Reference Freedman2017: 26) “it will be favourable” seems to relate the verb to the negative effects in the protasis. However, seeing as the verb kin.kin -ma appears directly before – which is situated in a logical relationship to sig 5 – and likely has the sufferer as subject, it is possible that this person is also the subject of sig 5.

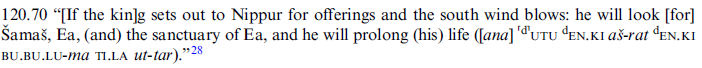

An additional terrestrial omen from tablet 120 of the Babylonian version of Šumma ālu indicates that such omens did in fact have bearing on the sufferer listed in the protasis (cited according to the edition by Huber Vuillet 2021: 17 with slight modification in the final phrase):

Though this omen differs in the two final verbal forms, it suggests a connection existed between seeking out a sanctuary to improve one’s quality of life. Furthermore, it indicates that the person suffering negative consequences in the protasis is understood as the subject of the verbs in the apodosis.

The recommendation to seek out sanctuaries in Šumma ālu may have been included because the action was known to supply good fortune to a person experiencing evil portents. In several of the examples the protases even mention medical conditions. Noticeably, none of the examples preserve the phrase sig 5 igi from the medical prescriptions, though they are slightly reminiscent. Depending on the interpretation, the omens could have a general positive value applicable outside the context of the protasis. Still, the phrase could be interpreted as a therapeutic statement with a concrete outcome related to the sufferer in question. It therefore appears that these omens held some inherent relationship to the medical traditions.

Some thoughts on the ears in ancient Mesopotamian medicine

Because most of the relevant prescriptions concern the ears, it is relevant to offer some thoughts on this area of the body. In ancient Mesopotamia, the ear was an orifice through which a person mainly received. As such, the ears are connected to wisdom, attention, dependability, and obedience in master-subject relationships.Footnote 29 High-pitched ringing sounds could also be indicative of ghostly communications, often in a negative context (see Scurlock Reference Scurlock2006: 5–20). Consequently, diseases affecting the hearing must have been considered problematic in ancient Mesopotamia, regardless of their medical severity. Furthermore, many ear ailments have observable as well as unobservable symptoms, which were apparently both assessed in the ancient medical text.Footnote 30 Infections in the ear are often extremely painful conditions that people experience on several occasions throughout their lives. Due to the interconnectedness of the ear and throat, pains in the ear(s) could even cause discomfort while drinking and eating, though this does not appear to have been a primary concern in the ancient symptom descriptions relating to the ears. In the past, such infections were not easily cured, and if left untreated, some of these conditions could develop into serious afflictions causing hearing loss and even meningitis (e.g., Jamal et al. Reference Jamal, Alsabea and Tarakmeh2022). Individual ear infections could force the patient to become bedridden due to vertigo, which would have signified a worsened condition than being able to move around.Footnote 31 Hence, pain and pus leaking from the ear must have portended poorly in prognostic terms, which could foreshadow more severe symptoms or potentially the onset of a serious disease. Perhaps this is the reason why few of the relevant prescriptions, such as Text nos. 2-3 in Appendix 1, contain diagnoses, as the treatments only targeted the initial problematic symptoms. Thus, ancient medical texts acknowledged the potential for serious complications by treating emerging and foreboding states of the ears.

Why is the advice to seek out sanctuaries of deities mainly found in prescriptions for treating afflictions of the ear? At least one manuscript, BAM 318 from the N4 text collection in Assur (Pedersén Reference Pedersén1986: 63 no. 149), indicates that supplication to gain favour included concrete ritual actions in the temples of deities, during which the ear played a central role. The ritual tablet contains three ritual instructions and incantations for soothing the anger of a god (col. iii 38: uz-zi DINGIR tu-na-aḫ-ma; see also col. iii 35; col. iii 39; rev. iv 1; rev. iv 7) and making the deity favourably inclined towards the patient (rev. iv 1: ⸢ šà -bi ⸣ dingir silim -ka; see also col. iii 38) by having the patient enter the temple of the god (col. iii 38: ana é dingir ku 4 -ma; see also col. iii 39; col. iii 43), carry tamarisk wood (col. iii 36: giš bi-nu; see also col. iii 40; col. iv 5), and put it behind his (left/right) ear (col. iii 37: ina ku-tal geštu zag -ka gar -an; Schwemer 2013: 188-189, 193, 197-198). The text shows that such actions were known in relation to soothing a deity’s anger, and the instructions inform us about two aspects of healing, which were central in at least this ritual: (1) the patient could be required to soothe the anger of a deity (responsible for the affliction) directly at a place of prayer (é dingir); and (2) the ear played a role when altering divine anger. However, as noted by Schwemer (ibid.: 184) these instructions are without known duplicates, and it is therefore questionable if they can be regarded as common practice.

Yet, the symptom descriptions specify in some instances that pus was discharged from an ear (e.g., Text no. 10), which might have been regarded as a source of contamination. If the patient went to an official temple, it is unclear what the parameters would have been for entering the public spaces of this building if the patient had visible medical symptoms.Footnote 32 However, only few of the symptom descriptions seem to comment on the state of the skin, colour, and swellings on the outside of the ear.Footnote 33

Though the āšipu was formally in charge of soothing the anger of a deity responsible for a sickness (Heeßel Reference Heeßel2000: 81-87), it appears that patients could perform concrete ritual actions themselves at places of worship to soothe the divine anger. This approach could potentially have bypassed the system of Assyrian and Babylonian healing established by Nils Heeßel (Reference Heeßel2000: 95), though the patient may have sought the sanctuary of a deity on the initiative of the healer. Therefore, the healer could, in less severe cases, encourage the patient to mend the divine relationship, though the healer himself established the parameters for a successful therapeutic treatment. From the examples discussed here, visits to sanctuaries seem to have been prescribed only in cases where the patient was not bedridden.

The significance of gaining good fortune

The phrase “the patient will (continuously/assiduously) seek out the sanctuary of DN, and he will experience good fortune” can be found in 11 medical prescriptions treated in Appendix 1. The phrases always occur in the symptom descriptions before the actual prescriptions designed to heal the patient. They are therefore listed as a sort of prerequisite for the cure alongside specific medical symptoms. While all previously known examples only contain this information (Text nos. 4–11), at least one prescription in the recently published Hama manuscript contains the addition that the good fortune will occur on a specific day or last for a number of days. Concretely, Text no. 1 states “on the 6th day/for six days, he will experience good fortune” ina u 4.6.ka[m] ⸢ sig 5 ?⸣ igi (cf. Text no. 2).Footnote 34 How should this addition be interpreted in the context of the role these instructions played in healing?

Generally, instructions for seeking out sanctuaries are only found in a handful of medical manuscripts from ancient Mesopotamia in texts regarding diseases of the ears and the ṭulīmu. In all cases the instructions were written in the symptom description instead of the following prescriptions designed to cure the patient. This suggests that the instructions were not part of the actual cure administered by the healer, but a prerequisite for the succeeding cure to be carried out. The only exceptions appear to be BAM 77 and 78 (Text no. 12), in which the symptom description regarding the ṭulīmu ends “when/after he continually seeks out the sanctuary of Marduk, he will recover” (ud aš-rat d amar.utu kin.kin -ma TI) before presenting a prescription, which is also said to heal the patient (TI). Though these examples may seemingly support Stol’s suggestion that the phrase “experience good fortune” (sig 5 igi -mar) was synonymous with “he will live” (ti), the phrase in BAM 77 and 78 occurs in a different context regarding another type of ailment. Given that the sentence also differs by specifying that the healing is received “when/after” seeking out the temples, I am hesitant to adopt the synonymous interpretation of “he will live” with “experience good fortune” for all the prescriptions.

Specific days in the month played a role when administering therapeutic remedies, and certain days were considered inauspicious for performing healing. For example, both physician (asû) and diviner (bārû) are mentioned in the hemerologies, and particularly the phrase “a physician should not reach out his hand to a sick man” shows that certain days of each month were considered inauspicious for medical treatment.Footnote 35 Such instructions are reminiscent of Sa-gig, in which the exorcist is instructed, in cases where the patient’s health shifts from day to day or specific ailments plague the patient, to avoid making predictions about the patient’s life.Footnote 36 Though hemerologies are well attested in the first millennium B.C.E, they remain difficult to interpret in a socio-religious context. Still, it is reasonable to assume that the inauspicious days listed in such works were problematic for patients. It is difficult for us to believe that people in ancient Mesopotamia would have been denied immediate medical action on account of inauspicious days. And even though this may have been the case, the evidence from the Hama manuscript indicates that these inauspicious days could be altered. Regardless of whether Text no. 1 refers to a range of six days or the 6th day in a period (after haven fallen ill?), it indicates that it was possible for a patient to alter one or more days so they became favourable. Some of the relevant prescriptions, such Text no. 1, even states that someone (patient or healer?) was to repeat (gur.gur -šú/šum) the prescribed healing action for a number of days, typically seven (Arbøll Reference Arbøll2023: 157–159). If the healing action needed to be repeated over several days, of which some might be considered inauspicious days for healing, it would have been less problematic for the healer or patient to repeat the treatment after the divine favour had been granted.

I therefore propose that the purpose of gaining divine favour was to obviate inauspicious days for healing. Although the Nineveh and Babylon manuscripts do not specify when the fortune was taking effect, the Hama manuscript does. And seeing as some prescriptions specify that the cures were to be repeated over a number of days, it is possible that visiting a deity’s sanctuary made these days favourable. This interpretation also explains why the phrases were listed in the symptom descriptions instead of the prescription, as they can be considered prerequisites for performing the healing procedure, not a part of it. Alternatively, the divine favour was simply meant to create auspicious omens for the patient when subsequently receiving a diagnosis, prognosis, or the healing itself, as suggested by Seux (Reference Seux1966: 174) and later Stol (1991–92: 57). Regardless, it is noteworthy that so relatively few prescriptions in the entirety of the medical corpus preserve similar instructions to gain divine favour, seeing as many cures could have relied on similar actions. This issue cannot be resolved at present.

Context of the available manuscripts

Both archaeological context as well as surviving colophons may inform us on the settings in which the cures were used, either in terms of scholarship or practice. Of the manuscripts edited in Appendix 1, BAM 503+ is by far the longest. This two-columned library manuscript, alongside its duplicate(?) K.15236, were excavated in the royal libraries of Nineveh, and BAM 503+ may once have held an Ashurbanipal colophon. Because the colophon is lost, it is unclear if it was part of the therapeutic series “If the crown of a man’s head is feverish” (šumma amēlu muḫḫašu umma ukāl; see recently Arbøll Reference Arbøll2021: 235–237). Presumably, BAM 503+ represents the sole manuscript expected to appear after the sections dealing with cranium and eyes (Steinert et al. Reference Steinert, Panayotov, Geller, Schmidtchen and Johnson2018: 209–210), though it cannot be determined which recension of the series it belonged to.Footnote 37 A partial duplicate, BM 41289+, is a Late Babylonian fragmentary two-columned manuscript from Babylon, which does not preserve a colophon and it is unclear where in Babylon it was excavated. Two single-columned manuscripts, BAM 77 and 78, were both excavated in Assur in the semi-private N4 text collection, which was clearly geared towards training and practice.Footnote 38 A colophon is only preserved on BAM 78, which underlines the practical aspects of this text by stating that the tablet was “For undertaking a (ritual) procedure (of) Kiṣir-Aššur, the s[on of Nabû-bēssunu] the exorcist of the temple of [Aššur]. Qui[ckly extracted. Writt]en and ch[ecked].”Footnote 39 Finally, the two-columned Hama manuscript was excavated in Building III at Hama, which the excavators believed functioned as a temple (Arbøll Reference Arbøll2023: 50–56). Though it is uncertain who used the texts discovered in this building, and for which purposes, it is noteworthy that the text mentions seeking out sanctuaries of deities while having been posited in an actual temple. Disregarding BM 41289+, the material in question relates to the first half of the first millennium B.C.E., albeit from two diverse geographical regions, namely Assyria and the Levant.Footnote 40 In terms of the Hama tablet, it cannot be excluded that the contents were intended for localised practice differing in some aspects from Babylonian healing. Nonetheless, the texts from Assur were copied by practitioners with an unclear relationship to the Aššur temple, and the manuscript from Hama was discovered in a temple, which might indicate that the sanctuaries referred to in the instructions should be identified as official temples.

In a broader context, only few additional medical manuscripts concern diseases of the ears,Footnote 41 although these afflictions must have been a widespread problem for many people in ancient times. In addition to the prescriptions treated here, the manuscripts also share duplicate passages with another relevant manuscript, namely AO 6774 (Geller Reference Geller2009). This text may have been from Assur, though its exact provenience is uncertain. It likely originated within an assemblage of two other medical texts, namely AO 7760 and AO 11447, all three presumably from Assur (Geller Reference Geller2007). In the most recent text editions of these texts, Geller (Reference Geller2007: 4 and n. 4) hypothesised that they were written by students of medicine, mainly because the colophon of AO 11447 mentions a certain Urad-Nanaya who may, or may not, have been a famous asû from the royal court at Nineveh during the reign of Esarhaddon. The question remains which profession(s) used the prescriptions in which a patient was encouraged to visit a sanctuary?

Two professions related to the medical manuscripts treated above appear to have been the main practitioners of their contents, namely the physician (asû) and exorcist (āšipu/mašmaššu). It is well known that the physician (asû) did not practice in a temple context (Geller Reference Geller2010: 43, 50), though the exorcist (āšipu/mašmaššu) had an unclear role in relation to such institutions in various periods (see references in n. 4). While prescription literature is largely believed to have originated with the asû’s profession (Steinert Reference Steinert2018a: 181, 187-188), it was also practiced by exorcists, such as Kiṣir-Aššur, in the Neo-Assyrian period (Arbøll Reference Arbøll2021: 4–9). The fact that prescriptions mentioning a patient seeking out a divine sanctuary can be found in the context of the āšipu, and possibly asû, in the Neo-Assyrian period points to an overlapping use of this healing approach among these two professions.Footnote 42 Though the symptom descriptions advising a patient to seek out a deity’s sanctuary do not appear to involve the healing practitioners themselves, the possible association with the asû indicate that such healers, unrelated to temple institutions, may have instructed patients to use deities’ sanctuaries to gain the divine favour needed to carry out a cure.

Conclusion

Temples did not hold a central place in Mesopotamian healing beliefs, though patients were occasionally encouraged to seek out divine support. As discussed in this article, prescriptions related to the ears and the spleen/pancreas (ṭulīmu) show that patients were encouraged to seek out sanctuaries of specific deities as a prerequisite for receiving the subsequent cure administered by the healer in question. During such visits, the patient might have reversed the negative omens put in place by the medical symptoms by “experiencing good fortune” (dumqu amāru). Although it remains unclear if the word aširtu designated private/local chapels or official temple complexes, places of worship were sought out to receive this reversal of fortunes.

The ears may have held a place in supplications intended to gain divine favour, at least in one ritual context. Provided it is possible to generalise on the basis of such documentation, this observation may explain why patients suffering from diseases of the ears went to divine sanctuaries to petition deities, but such actions may simultaneously have partly bypassed the ordinary system of Assyrian and Babylonian healing. On the basis of a new manuscript from Hama it was argued that the instructions to seek out the temples of deities in order to gain a better fortune may have been a way of circumventing inauspicious days for practicing and receiving healing. The question remains if such actions were self-explanatory in other healing literature where similar actions are not listed.

Finally, the manuscripts on which the relevant prescriptions are found appear to have been used by āšipu/mašmaššu-exorcists, and possibly also asû-physicians, in the Neo-Assyrian period. Though these professions are often seen as dichotomous, their overlap in practice during this period underlines that the material they drew on was equally incorporated into the practice of each discipline.

Appendix 1. Relevant symptom descriptions in medical texts

In the following I have provided editions of symptom descriptions referring the patient to the sanctuary of a specific deity. For in depth commentary on the prescriptions from Hama, see the individual references in Arbøll Reference Arbøll2023.

Overall, most of the prescriptions below contain the phrase sig 5 igi-(mar) “he will have good fortune” (see ibid.: 163). In these phrases SIG5 must be read dumqu “good fortune” or perhaps damiqtu “favour, good will, luck” to accommodate amāru “to see, experience”, which occur together in an idiomatic phrase concerning fortune (CAD A/2: 9; CAD D: 64–67, 73–74). Though sig 5 can also be read damāqu “to improve”, this was likely not the nuance here, as these phrases are part of the overarching symptom descriptions and prerequisites for the following cures designed to cure the patient (ana ti -šú …). This differs from other translations, e.g., by Scurlock and NinMed online, though these differences have not been systematically noted. For translations of Text nos. 3–11, see also NinMed online.

The writing kin.kin for šeʾû, found in several of the prescriptions below, implies a repeated action in Gtn-stem or an intensified action, such as D- and Š-stem. In the cases where kin.kin is written, I have translated the verb as Gtn-stem, although I acknowledge that there are a number of uncertainties.

In addition to the previously published tablets edited below, three further manuscripts are included. These are K.17098 (P402476, unpublished), a fragment listed in Lambert’s Nachlass, which Strahil Panayotov identified as part of the final two lines of col. iii on BAM 503+, transliterated for NinMed and provided to eBL (Fragmentarium K.17098), K.15236 (P401255, unpublished), a fragment perhaps belonging to a duplicate of BAM 503+, identified by eBL (Fragmentarium K.15236) and brought to my attention by the anonymous reviewer, and BM 41289+44238(+)41373, three fragments of a Late Babylonian two-columned tablet from Babylon with duplicate passages to BAM 503+, and transliteration provided by Irving Finkel to eBL (Fragmentarium BM.41289+; Leichty et al. Reference Leichty, Finkel and Walker2019: 446, 474). Note the CDLI P-number for BAM 503 where a photograph can be found (P400233).

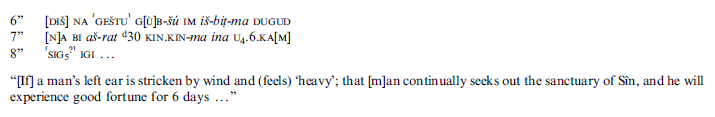

1. Hama 6A293(+)6A294(+)6A336(+)6A338 col. i 6’’–8’’ (collated from photographs)

Bibliography: Arbøll Reference Arbøll2023: 156–165, 221–227 (photographs, copies, edition)

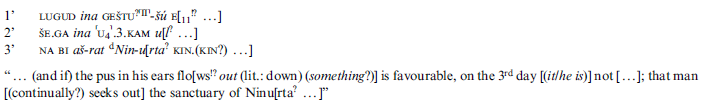

2. Hama 6A293(+)6A294(+)6A336(+)6A338 col. ii 1’–3’ (collated from photographs)

Bibliography: Arbøll Reference Arbøll2023: 156–165, 221–227 (photographs, copies, edition)

3. Hama 6A293(+)6A294(+)6A336(+)6A338 col. ii 6’’–8’’ (collated from photographs)

Bibliography: Arbøll Reference Arbøll2023: 156–165, 221–227 (photographs, copies, edition)

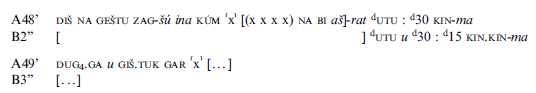

4. BAM 503+ col. iii 48’–49’ (ms A) and BM 41289+44238(+)41373 col. i 2’’–3’’ (ms B, Late Babylonian) (collated from CDLI and eBL photographs)

Bibliography: eBL Fragmentarium BM.41289+41373+44238 (transliteration); Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 376, 384 (edition)

Commentary: Ms B2’’ appears to specify that both the sanctuaries of Šamaš and Sîn/Ištar were to be sought out, as it contains the additional alternative Ištar. This alternative must be a later addition, as the remaining fragmentary lines appear to duplicate the prescription in ms A. However, the fact that the prescriptions stated Šamaš u Sîn may indicate the prescription should be treated as a separate entry unrelated to the entries edited here. In A49’, Scurlock translated the last part of the phrase as “people will listen to what he says”, Stol (1991–92: 57 n. 94) “to speak and being heard will be his lot”, and NinMed online “and then tell (his problem and) hear (the divine answer).” Though such nuances might be interpreted from the sentence, I have translated it more literally with the expected stative in the Sumerogram GAR, especially considering that we do not know what other outcomes came from visiting this sanctuary in the broken portion of the text.

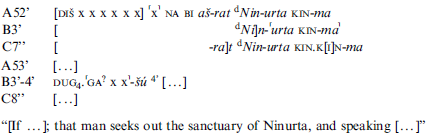

5. BAM 503+ col. iii 52’–53’ (ms A), K.15236 rev.? 3’ (ms B), and BM 41289+44238(+)41373 col. i 7’’–8’’ (ms C, Late Babylonian) (collated from CDLI and eBL photographs)

Bibliography: eBL Fragmentarium BM.41289+41373+44238 (transliteration); Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 376, 384 (edition)

6. BAM 503+ col. iii 57’–58’ (ms A) and K.15236 rev.? 7’–8’ (ms B) (collated from CDLI and eBL photographs)

Bibliography: Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 376, 384 (edition)

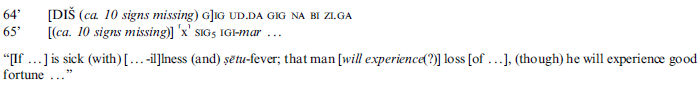

7. BAM 503+ col. iii 61’ (collated from CDLI photograph)

Bibliography: Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 376, 385 (edition)

Commentary: In line 61’, sa 6.ga can be read damāqu or damqu, which prompted Scurlock’s translation “he will experience improvement” of sa 6.ga igi -mar. However, the nuance here must be related to sig 5 igi -mar analogous to the related prescriptions. Consequently, I have translated it roughly in a similar manner. Few of the relevant prescriptions specify months, as they mainly provide a number of days or an unclear period of time.

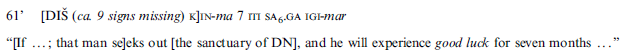

8. BAM 503+ col. iii 64’–65’ (collated from CDLI photograph)

Bibliography: Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 376, 385 (edition)

Commentary: It is unclear how to understand ZI.GA in this sentence, though if it refers to “loss”, it might be reminiscent of a partially broken sentence with inverted structure in Text no. 10 below. See also the somewhat uncertain translation by NinMed online “this man raises/remove/excited/he can get up (from his bed) […]” [sic].

9. BAM 503+ col. iii 72’–73’ (collated from CDLI photograph)

Bibliography: Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 376, 385 (edition)

Commentary: For the broken passage in 72’, see also the translation by NinMed online, which does not differ greatly.

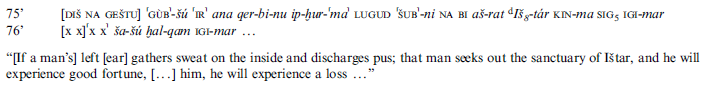

10. BAM 503+ col. iii 75’–76’ (collated from CDLI photograph)

Bibliography: Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 377, 385 (edition)

Commentary: In line 75’, the writing šub -ni for the expected present verbal form of nadû is unclear. The final syllable could designate a plural ventive ending, though the subject of the clause is singular. The broken passage in line 76’ is difficult to reconstruct. Scurlock translates “but that [sanctuary] will experience a loss” and NinMed online regards this as a reference to the patient seeking the sanctuary: “he will see loss […].” I agree that it must have a bearing on the patient, the question is why he experiences loss. Was it perhaps if he did the opposite somehow of seeking out the sanctuary of Ištar?

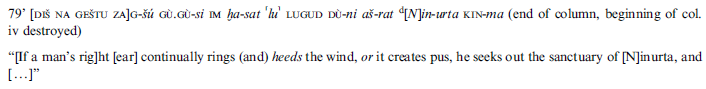

11. BAM 503+K.17098 col. iii 79’ (collated from CDLI and eBL photographs, and n. 30 in eBL edition, referring to Strahil Panayotov of NinMed who identified the fragment as part of this tablet)

Bibliography: eBL Fragmentarium K.2422 (edition); Scurlock Reference Scurlock2014: 377, 385 (edition)

Commentary: Scurlock translates the phrase starting with im as “(and) are pressured with ‘clay’”, though I have interpreted it differently. Several readings are possible on the basis of the signs ḪA-KUR, e.g., ḫa-sat (third singular feminine stative of ḫasāsu referring back to uznu, though this is ordinarily written out with s in both syllables) or ḫa-šat (the same form as before of a verb with one of the multiple meanings related to ḫašû). A reading ḫa-maṭ from the verb ḫamāṭu (a/u) “to burn, be inflamed” would be preferable, though it would be an incorrect form of the third masculine stative. This issue cannot be resolved at present. The partially visible ⸢ lu ⸣ in front of lugud is difficult to make sense of, seeing as the other symptoms are not introduced with this particle. Overall, this symptom description is the only example discussed in this paper, in which the patient is not specified as na bi “that man” before the recommendation to seek out a sanctuary.

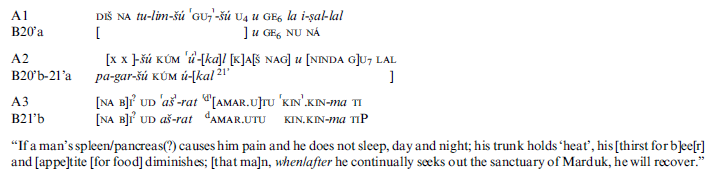

12. BAM 78 obv. 1-6 (ms A) and BAM 77 obv.? 20’–27’ (ms B) (both read from the copies)

Bibliography: Scurlock and Andersen Reference Scurlock and Andersen2005: 135–136 (partial edition); Stol Reference Stol2006: 113 (partial translation); Goodnick Westenholz Reference Goodnick Westenholz2010: 7 (partial edition)

Commentary: The ṭulīmu was discussed by Goodnick Westenholz (Reference Goodnick Westenholz2010: 7), and it may have represented the pancreas in humans. In ms A2 there is much room on the copy between ú and kal, which cannot be explained. It is of course possible to emend the reading to [kaš nag u ninda gu 7 i]-⸢ maṭ-ṭa(UD)⸣, as proposed by BabMed on CDLI for ms B21’, though I am hesitant to adopt this reading, because it is preferable to have na bi in such phrases related to seeking out sanctuaries. The UD after [na b]i ? is tentatively interpreted here as enūma (see, e.g., CAD I-J: 159–161). The presumed Gtn-stem in kin.kin in this sentence was rendered “assiduously” by Frazer Reference Frazer2015.