Introduction

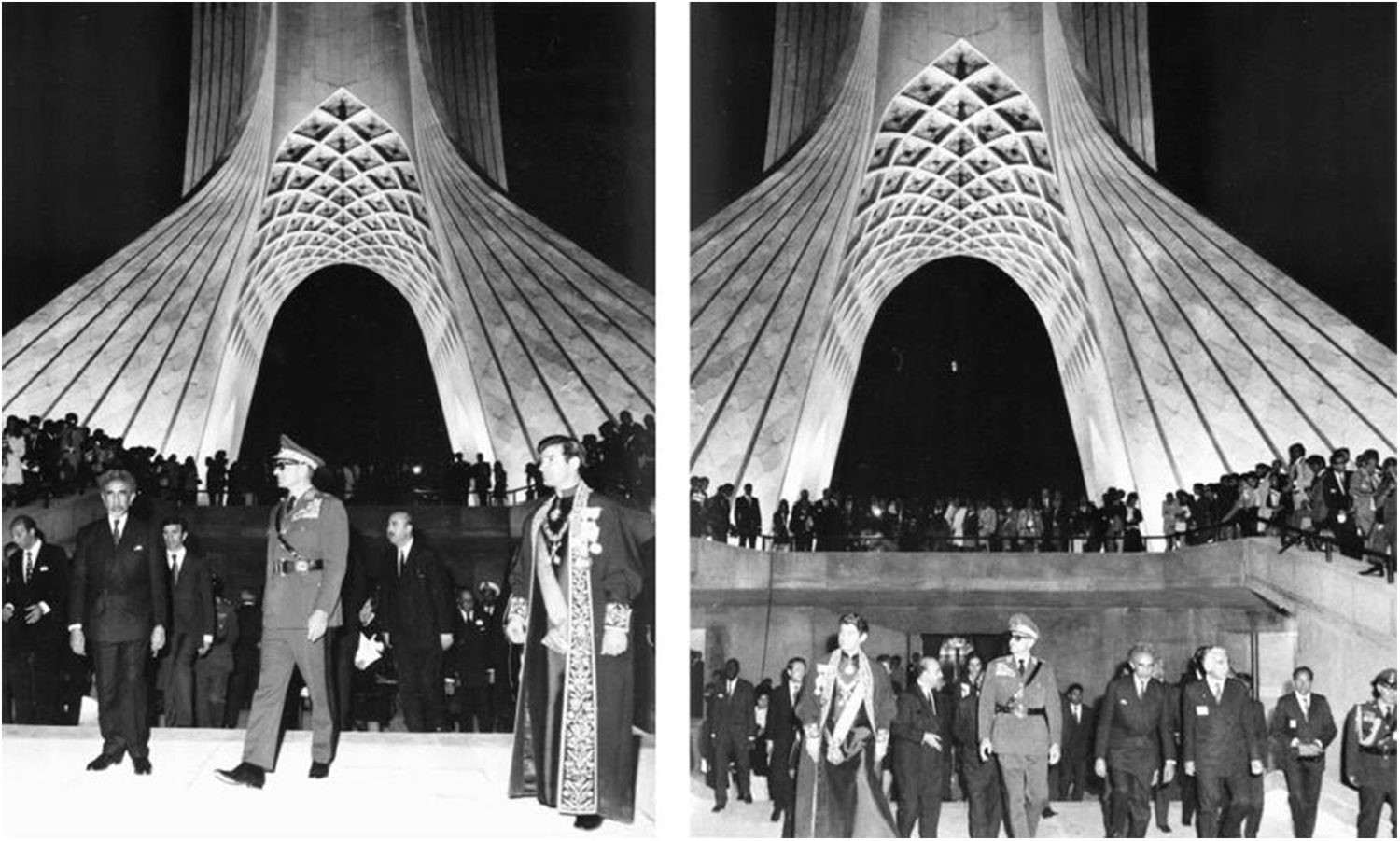

On October 17, 1971, at approximately 18:30, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (r. 1941–1979) entered Shahyad Square – an oval-shaped square located in western Tehran near Mehrabad International Airport – to inaugurate the Shahyad Aryamehr Monument, currently known as Azadi Tower.Footnote 1 This forty-six-meter-tall tower was constructed to commemorate the Iranian monarchical institution and was unveiled during the “2,500th Anniversary of the Founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great,” colloquially known as the Imperial Celebration.Footnote 2 Upon the shah’s arrival, the Iranian public who had gathered in the square to witness the imperial motorcade chanted “Javid shah” (Long live the shah). Dressed in his supreme commander’s uniform, the shah proceeded towards the main stage, flanked by heads of state including Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia, King Frederick of Denmark, King Hussein of Jordan, King Olav of Norway, Princess Grace and Prince Rainier of Monaco, Prince Philip and Princess Anne of the United Kingdom, and King Constantine and Queen Anne-Marie of Greece (Figure 1).Footnote 3 Military bands from countries such as Jordan, Algeria, Pakistan, Romania, Kuwait, and Switzerland performed throughout the ceremony, adding to the grandeur of the occasion.Footnote 4

Figure 1. Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi and Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia during the Shahyad monument’s inauguration in October 1971 (National Library and Archive of Iran, 1971, Document Number: 4728647)

The inauguration, which concluded at 20:00, featured a speech by Tehran’s mayor, Gholamreza Nikpey, and a guided tour of the tower’s interior spaces, including two museums.Footnote 5 One museum, located directly beneath the main vault, showcased artifacts from pre-Pahlavi Iran, prominently featuring the Cyrus Cylinder – the official symbol of the celebration – on loan from the British Museum. The second museum, situated in the upper section of the tower, was designated as the Future Museum and exhibited displays portraying Iran’s perceived achievements and envisioned development during the Pahlavi reign.Footnote 6 The ceremony culminated in a fifteen-minute fireworks display, serving as the grand finale of the inauguration.Footnote 7

Approximately 3,000 individuals, pre-cleared by SAVAK (the Bureau for Intelligence and Security of the State), were admitted into the highly secured Shahyad Square to attend the inauguration. This select audience included monarchs, presidents, ambassadors, princes, and other dignitaries from nearly fifty nations, alongside Iranian cabinet members, parliamentarians, senators, scholars, journalists, and the royal family. Among the attendees, a lesser-known but significant group of nearly 300 individuals represented the funders of the tower. According to the Iranian government, these donors contributed 452,200,200 Iranian rials (approximately USD 6,000,000) to fully fund the tower, exempting the government from any expense.Footnote 8

While the Shahyad Aryamehr Monument has received considerable scholarly attention, perhaps more than any other modern Iranian monument, its funding model remains underexplored, with limited scholarly works investigating the donors’ identities and significance to the shah’s agenda and celebration’s objectives, despite their prominent inclusion in the inauguration’s ceremonial narrative. This study addresses this gap by examining both the donors and funding model within the celebration’s broader domestic and diplomatic objectives. Situated within the discipline of architectural history, this paper contributes to the understanding of philanthropy in the celebration’s architectural projects and the state’s strategic use of architecture to project the monument’s funding model as a symbol of Iranian support for modernization.

Architecture, in this context, is interpreted as material culture – comprising artifacts, adornments, landscape modifications, and applied arts that serve as “unconscious backdrops to daily routines,” eliciting tangible and emotional responses to abstract concepts.Footnote 9 Anne Gerritsen and Giorgio Riello have highlighted how this approach destabilizes the traditional primacy of written accounts in historical studies, allowing historians to engage with previously overlooked themes, including the intersections of politics, trade, modernization, architecture, and fashion.Footnote 10 Within this framework, architecture encompasses processes, products, and cultural narratives that shape environments and convey meaning to diverse audiences with varied interpretations. The significance of patronage in examining architecture as a material artifact has been extensively analyzed in material culture studies, where the complex interplay of patron and creator often reveals a mutually beneficial dynamic.Footnote 11 Scholars have demonstrated that patronage frequently serves to advertise and bolster the social and political standing of patrons while simultaneously elevating the status of the commissioned artist, both nationally and internationally.Footnote 12

By reading the Shahyad monument as material culture, this study draws on four sets of primary sources: archival documents, print media, and historical photographs and videos, supplemented by oral histories. Persian-language archival documents, visual materials, and print media were obtained from the National Archive of Iran in Tehran and Shiraz, while English-language sources were accessed through Newspapers.com™, an online archive. Oral history materials were retrieved from the Harvard University Iranian Oral History Project. These largely unexamined sources inform the study’s exploration of the following questions:

• Who were the Shahyad monument’s funders and to what extent were their contributions voluntary?

• Given donors’ prominent inclusion in the inauguration ceremony, why was the promotion of the Shahyad funding model pivotal to Iran’s public relations, diplomacy, and heritage-making?

• What messages did the Shahyad funding model aim to convey to domestic and international audiences?

• How did the Shahyad funding model seek to redefine Iranian heritage and national identity?

• How did the monarchy reinforce and showcase the Shahyad funding model?

Shahyad monument donations in a broader context: Donations of the Persepolis dense plantations and commemorative schools

In 1960, in one of the earliest designing and planning initiatives of the celebration, it was decided that “a permanent monument like a victory arch at the entrance of Tehran, to be used when foreign heads of state enter the country,” would be constructed.Footnote 13 However, several commissioned designs failed to receive the shah’s approval and the celebration itself was postponed multiple times, primarily due to a lack of financial and infrastructural resources.Footnote 14 In 1966, a national architectural competition led to Hussein Amanat’s selection as the tower’s architect.Footnote 15 After nearly five years of planning and construction, the tower was completed in 1971.Footnote 16

The celebration’s organizers claimed that 290 industrialists and merchants funded the Shahyad monument’s construction. According to Keyhan newspaper, these donations were intended to “show their gratitude for the recent economic advancements of the country.”Footnote 17 Contemporaneous pro-Pahlavi media echoed similar sentiments. The celebration’s official newspaper described the contributions as “an utmost sign of gratitude to the leadership of the Shahanshah,” while the Information and Publication Committee of the Central Council for the Imperial Celebration’s weekly publication heralded the donors as “patriot and Shah-lover merchants,” who not only funded the monument but also covered the costs of its inauguration.Footnote 18 Peter Ramsbotham, the British Ambassador to Iran (1971–1974), similarly reported to the UK government that the Shahyad monument had been financed “entirely by grateful millionaires,” according to official claims.Footnote 19 Shortly after the celebration, Court Minister Asadollah ‘Alam (1919–1978) confirmed in a press conference that the monument’s cost, including for its landscaping and museums, totaled IRR 452,200,200 (approximately USD 6 million), all of which was funded by Iranian donors. Donations ranged from IRR 5,000–13,000,000, predominantly from “industrialists, merchants, and bank managers”; ‘Alam explicitly emphasized that no government funds had been used.Footnote 20

Archival documents and contemporaneous print media refer to the donors only in generic terms, without providing specific names. For instance, in correspondence dated May 2, 1971, ‘Alam informed Manuchehr Eqbal (1909–1977), the head of the National Iranian Oil Company, that an additional IRR 2.86 million had been received from “industrialists, contractors, and construction firms.”Footnote 21 While the letter included precise check numbers and bank names, it omitted the donors’ identities. According to this correspondence, the aggregated donations amounted to IRR 427,094,750, suggesting that an additional IRR 251,052,250 were collected in the final three months leading up to the inauguration. Similarly, an earlier correspondence from the Finance Committee of the Central Council of the Imperial Celebration – a comprehensive organizing body overseeing the event – attributed a donation of IRR 294,000 to “individuals,” without providing any details of their identities.Footnote 22 A more notable contribution was credited to the Association of Iranian Banks (AIB), a nonprofit entity comprising public and private Iranian banks, which had pledged IRR 10 million to the monument’s construction.Footnote 23 Elsewhere in the archival materials, more substantial contributions are documented, but they all originate from public entities. For instance, the National Oil Company donated IRR 1 million, while the Planning and Budget Organization (PBO) and the Municipality of Tehran jointly contributed IRR 70 million to the tower’s construction.Footnote 24

The total amount of traceable contributions from entities such as the PBO, AIB, and Municipality of Tehran falls significantly short of the total project costs. According to official claims, the remaining funds came from a nameless, homogeneous consortium of “industrialists and merchants.” Abdolreza Ansari, deputy head of the Central Council, recently noted in an interview that these donors were members of Iran’s Chamber of Commerce and Industry who were invited to the royal court and presented with the opportunity to contribute to the celebration.Footnote 25 Similar sentiments appear in internal correspondence among members of the Central Council. For instance, Amir Motaqi, director general of the Ministry of the Imperial Court, wrote to ‘Alam, stating:

Those who are wealthy and who have reaped greater financial benefits from the security and stability achieved under our Shahanshah’s reign must now fulfil their obligation more fully by covering the costs of this celebration – an unquestionable debt they owe to our great Shahanshah – and bear the burden of these expenses upon their own abundant resources.Footnote 26

The extent to which these were voluntary contributions is a critical question, particularly when viewed in the broader context of the celebration’s donation practices. Motaqi’s and Ansari’s remarks bear striking similarities to the donations solicited for the so-called Persepolis Artificial Forest (Jangale Masnooeie Takhte Jamshid), a dense, sixty-acre plantation developed as part of the celebration’s preparatory efforts.Footnote 27 Mehdi Pirasteh, then governor of Fars Province, where Persepolis is located, was tasked by the shah and Central Council with preparing Shiraz and Persepolis for the celebration, originally planned for 1964.Footnote 28 Upon inspecting the site, Pirasteh noted: “In front of Persepolis, people had hung clothing lines, built tin shacks, and created something resembling those very primitive slums you’d find in the south of Tehran, only even more basic.”Footnote 29 To enhance the area’s visual appeal for foreign dignitaries, Pirasteh orchestrated the relocation of the slum dwellers and established a dense plantation of pine, cypress, and ash trees on the western side of the Persepolis terrace.

Lacking formal budgetary approval, Pirasteh solicited funds from local farmers and landowners. Farmers selling sugar beet to the Marvdasht Sugar Beet Company were “given an opportunity” to pay “10 Shahi [approximately IRR 1.5] per ton of sugar beet by their consent” to cover the costs of relocating slum dwellers. According to Pirasteh, between IRR 300,000–400,000 (approximately USD 3,750–4,750) was collected, with each dweller receiving IRR 20,000 to find new housing and an additional IRR 25,000 if they dismantled their slums themselves.Footnote 30 Donations also extended to include land, seedlings, water, and labor provided by local farmers and landowners.Footnote 31

In an interview with Zia Sedqi for the Harvard University Iranian Oral History Project, Pirasteh portrays these contributions as entirely voluntary, although archival records reveal otherwise. Landowners from Jalal-Abad, a village near Persepolis and Marvdasht, later filed lawsuits against ‘Ali Sami (1910–1989), an archeologist and head of the Persepolis Scientific Institute (Bongahe Elmi-e Takht-e Jamshid), and Jamshid Kousheshi, the head of the Marvdasht Sugar Beet Company, for the “forcible acquisition” (tassarrof-e odvani) of their lands for the purpose of the plantation project.Footnote 32 While Sami and Kousheshi had collaborated with Pirasteh to develop the Persepolis forest, landowners conspicuously avoided targeting the governor, reflecting their limited options.Footnote 33 In an authoritarian setting with underlying threats of violence, forcible acquisition, or imprisonment, local farmers and landowners did not have many options but to welcome the opportunity for donations and, in turn, project their frustrations onto those who did not have the power to enforce further restrictions.

A handwritten petition dated November 26, 1960 in the National Archive of Iran provides further evidence challenging Pirasteh’s depiction of voluntary philanthropy. Signed by nearly forty individuals in a tone of desperation, the petition urged Pirasteh to allocate land and financial support to residents whose houses were within the plantation project:

These houses are the result of thirty years of hard labor and dedication at Persepolis, where we worked tirelessly for low wages, driven by immense passion. After much pleading, persistent requests, and numerous letters to the government, we were granted permission to build homes on the lands of Persepolis … Now, with Your Excellency’s directive for tree planting in front of Persepolis, we humbly request arrangements to be made for housing for us, so that we are not left homeless and destitute in the harsh depths of winter.Footnote 34

Whether the shah and royal court were aware of the forced possession of land for Pirasteh’s landscaping projects remains uncertain, but Pirasteh’s account offers some insight. In his interview, Pirasteh claimed that during a 1961 visit to Persepolis by the shah and Queen Elizabeth II (r. 1952–2002), the shah praised Pirasteh’s work and suggested extending the plantation up to Marvdasht, eighteen kilometers away. Portraying himself as a just governor, Pirasteh recounted his response:

I am certain Your Majesty does not wish for any injustice. Perhaps 10,000 people, young and old, make their living from these lands. We don’t even know who owns them. It’s eighteen kilometers, and that would essentially be a death sentence for these people. Let us first study whether we can provide compensation or find some equitable solution.Footnote 35

According to Pirasteh, the shah immediately responded, “Yes, I’m not telling you to commit any injustice. Study it first.”Footnote 36

Elaborating on this case, during his interview, Pirasteh further suggested that many policies and actions attributed to the shah did not originate from the monarch’s direct involvement or intent. Instead, the shah often relied on advisors or officials who presented proposals without disclosing their full implications. In such cases, the shah typically acquiesced, assuming that necessary considerations had been made.Footnote 37 Pirasteh claimed that if anyone clarified that such plans involved expropriating land from ordinary people or causing undue hardship, the shah would refrain from endorsing those measures. However, what Pirasteh, perhaps intentionally, omitted is how he himself secured the shah’s approval to develop a dense plantation near one of Iran’s most significant historical sites, subject to strict cultural heritage regulations – a matter illuminated by archival documents.

Initially launched without authorization from the heritage preservation authorities, proponents of the Persepolis plantation project – led by Pirasteh – belatedly sought approval from the Society for National Heritage (SNH).Footnote 38 In a formal response, the SNH, under General Farajollah Aq-Avali (1888–1974), explicitly opposed tree planting within Persepolis’s primary protection zone, warning that archaeological materials buried up to three kilometers from the ancient complex could be at risk.Footnote 39 The SNH recommended establishing commemorative landscaping further away to safeguard the ancient site for ongoing and future research.

Despite these objections, Pirasteh persisted. Encouraged by “Engineer Rahmani,” the planner responsible for the forest design, Pirasteh sought direct royal endorsement as a strategy to bypass Society for National Heritage (SNH) restrictions. In a handwritten, undated letter, Rahmani expressed concern that if the SNH presented its objections directly to the shah, the project might be halted.Footnote 40 By expediting the presentation of detailed, colored maps and emphasizing the plantation’s public and ceremonial benefits, the project’s supporters aimed to secure a royal mandate that overrode archaeological warnings. While no explicit evidence of a royal decree exists in the archival records, the NHA’s subsequent silence, the collaboration of figures such as ‘Ali Sami, and the plantation’s eventual completion suggest that Pirasteh leveraged the shah’s tendency to trust advisor assurances.

This precedent contextualizes Amir Motaqi’s proposal to the shah to outsource celebration costs to public contributions. It is plausible that the shah approved such initiatives as part of a broader strategy that had become commonplace under the monarchy. In a letter to the shah, Motaqi highlighted previous successes in fundraising for state projects:

As your highness is aware, I firmly believe that, given the respect all Iranians have for the monarchy of Iran – especially His Imperial Majesty Shahanshah Aryamehr, the builder of modern Iran – we can raise these expenses [for the Imperial Celebration] from fewer than 200 commercial and industrial enterprises, factories, and private banks. They will most willingly and eagerly participate in this national and historic celebration. We have taken this approach before; for example, by quietly inviting just 60 industrialists and merchants on two separate occasions in the past, we managed to collect 80 million rials [USD 1.1 million] for the construction of His Imperial Highness Reza Pahlavi’s industrial city in the Khorramshahr border region. That sum is currently deposited in the Omran Bank, and it will soon be used for the city’s construction expenses.Footnote 41

While public donations to state projects were not unique to Iran, the context provided by Ansari, Motaqi, and Pirasteh suggests that such contributions were often shaped by implied coercion and fear of reprisal. As Robert Steele notes, the land redistribution policies of the White Revolution had compelled many former landowners to transition into industrial sectors. These individuals were acutely aware that “the regime could, at any time, make things very difficult for their businesses … if industrialists had been invited to pay up for a common cause, then it would have been unwise to refuse.”Footnote 42 The underlying pressure, therefore, subtly enhanced philanthropic donations to the monarchy’s projects.

Further evidence supporting this observation can be found in the nearly 3,000 commemorative schools built through philanthropic contributions from Iranians and non-Iranians. Initially, the target was to construct 2,500 schools to commemorate the 2,500th anniversary of the monarchy. However, the eventual figure reached nearly 3,000, which was attributed to Iranians’ “eager participation.”Footnote 43 These donors were named and detailed in contemporaneous print media. For instance, Ayandegan published a report listing the donors and locations of approximately 300 schools, including prominent Iranian individuals, municipalities, and foreign contributors such as the Soviet Union’s Soyuz 11 astronauts, the US’s Philco-Ford company, and Prince Aga Khan I.Footnote 44

A significant portion of these contributions to the commemorative schools came from public or monarchy-affiliated entities, including municipalities, the Pahlavi Foundation, public banks, and members of the royal family, such as Empress Farah, Ashraf Pahlavi, and Gholamreza Pahlavi. Nevertheless, private individuals and organizations also played a meaningful role, indicating some degree of participation from the general public. However, the final figure – nearly 3,000 schools – would likely not have been achieved without contributions from Pahlavi-affiliated individuals and entities, alongside the implied obligation felt by the private sector. A similar dynamic is evident in the Persepolis Forest project. Archival records contain several letters sent to Pirasteh requesting recognition for the donations of local farmers and landowners, who contributed seedlings, water, and even labor to the celebration.Footnote 45 While these contributions reflect a mix of voluntary participation, the underlying obligation played a role in enhancing such involvement.

In the broader context of the celebration’s donations, however, the Shahyad monument’s donors emerge as a distinct and enigmatic case.Footnote 46 The detailed records of donors to commemorative schools and the Persepolis Forest contrast sharply with the anonymity surrounding the consortium of industrialists and merchants that funded the Shahyad monument, raising questions around the motivation for the latter’s prominent role at the monument’s inauguration. Why did this homogenous group – without recorded names, tastes, or political affiliations – receive such visibility during the celebration? What benefits did the shah seek by highlighting these industrialists and merchants, and how did their contributions align with the broader diplomatic and modernization narratives of the Imperial Celebration?

The significance of Shahyad monument donations to Iran’s international brand

From its conception in 1960 to its inauguration in 1971, the Shahyad monument was frequently compared to iconic global monuments, such as the Eiffel Tower, Arc de Triomphe, Golden Gate Bridge, Kremlin, Elizabeth Tower (Big Ben), and Statue of Liberty. For instance, during the celebration, Keyhan newspaper published a report highlighting architectural icons as the “birth certificates” of their respective cities. The report concluded: “with the construction of Shahyad, Iran issued its birth certificate.”Footnote 47 Similarly, the celebration’s official newspaper – a publication of 100 exclusive issues by the Ministry of Intelligence – described the Shahyad monument as “a birth certificate for Tehran,” noting:

Since the construction of the Eiffel Tower in 1889, the world has seen it as the symbol of France and Paris. French citizens are proud of the tower and how it attracts millions of tourists. The Golden Gate Bridge was built with a USD 35,000,000 budget and has represented the state of California in the United States ever since. The Kremlin palace in Moscow, the clock tower in London, the triumphant arch of Paris, the freedom statue in New York, and many other symbolic buildings throughout the world give a peculiar and distinct characteristic to their respective cities…. In a sense, these buildings function as an international language to introduce civilizational beacons.Footnote 48

Other articles in the same newspaper reiterated this narrative, positioning the Shahyad monument as a symbol of progress, development, and modernization under the shah. For example, Mohammad Hasan Ganji, a professor at the University of Tehran, remarked that the monument would give Tehran a unique identity and represent Iran’s capital to the world, just as the Eiffel Tower symbolized Paris.Footnote 49 Khandaniha, a popular Persian-language magazine, echoed this perspective, stating:

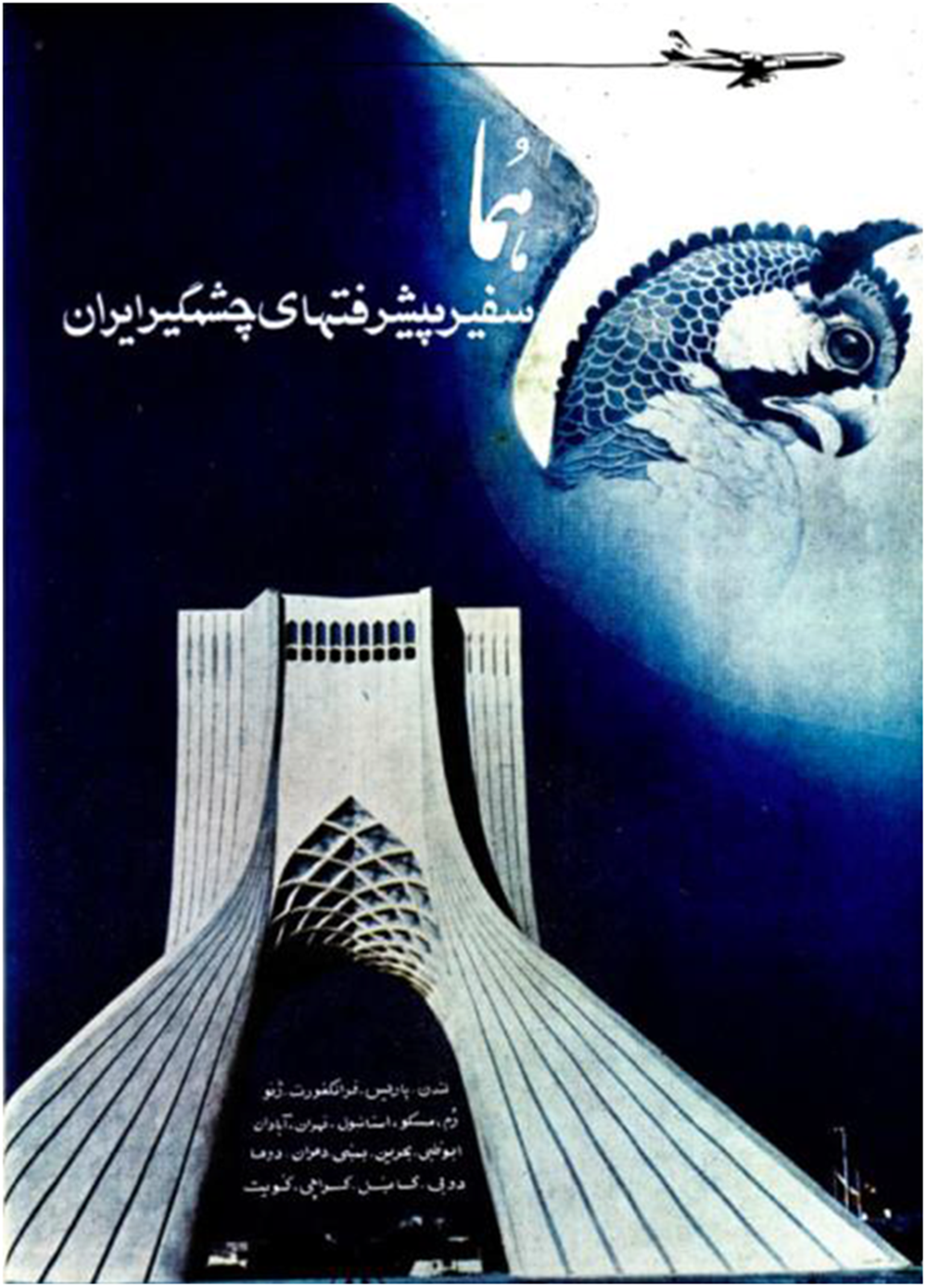

Airlines use the Eiffel Tower to represent Paris, the famous bridge for London, the Colosseum for Rome, and the Statue of Liberty for the US. From now on, they will use Shahyad to represent Iran. So far, airlines have used camel riders or women in traditional dresses to depict Iran, but Shahyad will now represent modern Iran.Footnote 50

This narrative framed the Shahyad monument as a marker of Iran’s transformation from a traditional, third-world country to a modern, progressive nation-state. Khashayar Hemmati has explored the concept of the monument as Iran’s international brand, analyzing its deployment by the Pahlavi monarchy in contexts ranging from international fairs to advertisements. Hemmati noted that the monument’s most prominent international representation was found in Iran Air (Homa) advertisements, which showcased it as a symbol of modern Iran. Furthering Hemmati’s supporting evidence, Honar-Va-Memari, the most prominent Persian-language journal on art and architecture in the 1970s, published an image of the monument in an advertisement for Homa (Figure 2). This promotional image highlighted the Shahyad monument as a symbol of Iran’s modernization, with the tagline “Homa: Ambassador of Iran’s Striking Progress,” linking the monument to Iran Air and the nation’s aspirations for global recognition.Footnote 51 The inclusion of the mythical Homa bird, the tower, and an airplane underscores the integration of tradition, international connectivity, modernity, and economic growth attributed to the White Revolution.

Figure 2. An architectural magazine advertising Iran Air using Shahyad imagery (Honar-Va-Memari 1972)

The White Revolution, launched in 1963, was a series of socioeconomic reforms aimed at modernizing the country while consolidating the monarchy’s power.Footnote 52 By 1971, it had delivered some tangible results: industrial growth rates of 15–16% annually, GDP growth averaging 10.5% per year, and reductions in illiteracy through programs such as the Literacy Corps.Footnote 53 The shah framed these reforms as Iran’s “pink path,” “a middle route superior to dark capitalism and red communism,” claiming it offered a model with universal appeal.Footnote 54 Publications such as The White Revolution, written by the shah and released in Persian, English, and French, attempted to promote this narrative globally.Footnote 55

However, the White Revolution was not without criticism. Ali Massoud Ansari has elaborated on the ideological construction of the White Revolution and its political discourse. According to Ansari, the White Revolution was intended as:

a bloodless revolution from above aimed at fulfilling the expectations of an increasingly politically aware general public as well as an ambitious and growing professional socio-economic group, and as such, anticipating and preventing what many considered to be the danger of a bloody revolution from below.Footnote 56

As set out by Talinn Grigor, the White Revolution projected the image of the shah as a modernizing revolutionary monarch at the vanguard of social change, enabling him to:

appropriate the various political, socio-economic, and cultural forces into his domain of power and thus gain unprecedented executive sway over significant agencies such as the Plan Organization, the National Iranian Oil Company, the Women’s Organization of Iran, and the Society for National Heritage.Footnote 57

Resonating with Grigor’s observation, Hossein Razi, one of the founders of the God-Worshipping Socialists (Socialist-haye Khoda Parast), an Iranian political party, argues that adopting some of the modern nationalist goals, such as reform, modernization and industrialization, were new authoritarian techniques to the old ways of absolutism.Footnote 58 This appropriation of political and cultural power by the shah was also seen by contemporaneous audiences. In 1971, for example, Asbury Park Press, in a report entitled “Oil Carries Iran Into the Modern World,” noted that – as a result of the “White Revolution” – the shah “does not reign, he rules.”Footnote 59

Therefore, as noted by Ansari, while the celebration could have been used to signal a genuine democratization process, even if incremental and gradual, the shah opted for an alternative emphasis, seeing the occasion as an opportunity to portray democratic governance without losing his authority and power.Footnote 60 As Afkhami explains, the shah believed that his concentration of power was not against the letter and spirit of the Iranian constitution. He often reassured himself that, “when it came to governance, there was something exceptional about Iran,” and Iranians “love their monarchy because it is the natural order.”Footnote 61 His propaganda system would often claim that Shahanshah (Shah of Shahs [king of kings]) was like a father, a tradition that dated back to Cyrus the Great.Footnote 62 In this conception, the contemporary monarch was perceived as central to national politics and functioned like a modern Cyrus, the primary historical figure of the celebration.Footnote 63

Returning to the Shahyad monument, the tower’s funding model emerged as a pivotal narrative tool for projecting the monarchy’s achievements and reinforcing its modernization agenda. Unlike global monuments that were typically funded by state or municipal authorities, Shahyad was framed as privately funded by Iranian industrialists and merchants – a gesture symbolizing their gratitude to the shah. This distinction emphasized Iranian “exceptionalism,” portraying the country’s modernity and democracy as uniquely participatory and distinct from its contemporaneous counterparts. Keyhan articulated this narrative, describing the Shahyad monument as:

a symbol of the gratitude expressed by Iranian industrialists and merchants who had notably profited from the country’s recent economic progress. In many developed nations, it is typically the government or municipal authorities that undertake the construction of such monuments. In Iran, however, Shahyad was erected by the private sector to serve and commemorate the celebration and Iranians as a symbol of art and beauty.Footnote 64

The emphasis on the role of industrialists is significant in these efforts because industrialization was central to the shah’s conception of progress, modernity, and the success of his White Revolution.Footnote 65 Donations to the tower’s construction were presented as an implied acknowledgement of the White Revolution’s material impact and, importantly, how well it was being received. Central to this message was the suggestion that the White Revolution had achieved significant land reform and diminished feudalism in Iran, leading to the emergence of a new social class – merchants and industrialists – who, according to the Shahyad funding model, were both successful and grateful to the shah.

Foreign media commented on the inherent tensions between the Shah’s reforms and traditional landowners, tensions that the funding model sought to mitigate by reinforcing the Shah’s image of popular support. For example, Vivian Williams, reporting for the Boston Sunday Globe, wrote: “The people of Iran cheer the Shah with genuine feeling when he moves among them, as he frequently does, but needless to say with such reforms behind him, he has genuine enemies among Iran’s dispossessed land-owning and business class.”Footnote 66 In this political context, the celebration’s emphasis on Iranians’ supposed voluntary donations attempted to underpin the shah’s path to modernity.

The Shahyad funding model, therefore, supported the monarchy’s broader objectives on several fronts: it symbolized Iran’s perceived progress following the White Revolution; differentiated Iranian modernity from its contemporaneous counterparts by projecting its top-down approach as a uniquely Iranian, progressive, and democratic; and demonstrated the positive reception and popularity of the shah’s monarchy and modernization programs among Iranians. Given these benefits, the celebration deployed a variety of methods to further project the Shahyad funding model to domestic and international audiences.

Projecting the Shahyad funding model in support of the shah’s modernization programs

Donations to the Shahyad monument were unlikely as voluntary or wholehearted as the monarchy claimed, especially when viewed within the broader context of the celebration’s donation practices, such as the Persepolis Forest project. However, what Shahyad’s carefully curated funding model ultimately shows is that the monument’s delivery was deployed as a potent form of political messaging: while monuments in other, perhaps more democratic, nations were typically government-funded, the Iranian national monument was framed as funded by its citizens – a symbol of gratitude to a shah who, though ruling rather than reigning, was seen as delivering well-received progress and modernity. This narrative was amplified through a range of tactics, such as publications and discourse, surrounding the project.

The first tactic deployed vigorously was the use of publications and public announcements to make it abundantly clear whose gratitude and generosity had made this “splendid new monument” possible. This tactic has been seen in many of such events.Footnote 67 In the case of the Shahyad monument, the intention was to proclaim that the shah’s White Revolution had disseminated wealth, gratitude, and satisfaction among the general public. A short article published in the celebration’s official newspaper, entitled “Shahyad’s Message for Future Generations,” serves as an example. It noted that “what we build today is the message of our generation and era to the future generations and eras,” and continued by arguing that Shahyad had been “built by industrialists of the bright era of Shahanshah Aryamehr as a message to the future.” According to the author, such messages included a demonstration of “how Iran managed to end feudalism, release cities from pastoral and rural economies, and build the society on the industrial economy.”Footnote 68

In a report published by Keyhan a few days after the celebration, the rhetoric was further linked to Tehran’s transformation into a modern capital city:

[The private sector has built Shahyad] and gifted it to all the people who recognized Tehran as Iran’s largest, most populous, and most modern city. With Shahyad, the west of Tehran is on the right track towards progress and prosperity. This part of Tehran will attract massive capital from the private sector in the future. Any project like Shahyad executed in any corner of Tehran or other cities of Iran is undoubtedly a sign of Iran’s development and progress in industry, trade, and business. It also signals Iranians’ deep affection for their country and the development of its cities, evidenced by all the various buildings they erect in every corner of the country, showcasing Iran’s bright and glorious image.Footnote 69

Even the non-Persian print media reiterated the message. The Chicago Tribune, for instance, noted that “When the Shah was born in 1919, Tehran was a pleasant retreat for courtiers and landlords. Today Tehran is a city of boulevards, clogged by cars that pour out of its four assembly plants.”Footnote 70 In another report, entitled “The Shah: A Popular Monarch Has Led Iran Far, But Some Grumble Quietly,” Crocker Snow, reporting for the Boston Globe, noted:

Like the 1964 Olympics or Expo ‘70 in Japan, the event [Imperial Celebration] has prompted Iran to wash all over and dress itself up. The effect has been felt not only in badly needed new hotels and highways but also with the equally necessary 2,500 new schools which are being opened this year in connection with the anniversary.Footnote 71

A 1971 newspaper published in the US state of South Carolina further supported this interpretation. In a report entitled “All Iran Roads Lead to Tehran,” the paper noted:

Tehran’s visitors will see modern squares and six-lane boulevards as well as ancient mosques and bazaars. Slums are gradually disappearing as modern hotels and high-rise apartments appear. The capital city’s population has doubled to three million over the last 15 years.Footnote 72

Beyond the written discourse, the imagery associated with the Shahyad monument further underscored the narrative of Iranian industrialists financing the project. For instance, the comic book Azemat-e Bazyafte [Regained Glory], published after the celebration, depicted the monument’s inauguration, with the shah in military uniform and framed by fireworks and a crescent moon (Figure 3). This striking composition symbolized celebration and grandeur, conveying themes of national pride, modernity, and reverence for the shah’s leadership. The accompanying caption read: “The people of Iran, grateful to their Shahanshah, erected an immense and beautiful building, named Shahyad Aryamehr after the Shahanshah. This monument is one of the great masterpieces of architecture in the world.”Footnote 73

Figure 3. Shahyad as the symbol of Iranian gratitude (left, the celebration’s newspaper, 1971; right, Regained Glory, 1976)

The choreography of the inauguration ceremony further reinforced this narrative. Upon the shah’s arrival in his Supreme Commander uniform, donors chanted “Javid Shah” (Long live the Shah), joined by 7,000 Iranians gathered outside the secured area, placing the shah at the center of attention. This orchestrated presence was presented as a voluntary act demonstrating “their [the people’s] faith and commitment” to the Iranian monarchy, “with the most fervent emotions.” The first page of the celebration’s official newspaper the following day prominently featured an image of the shah “responding to citizens’ expression of emotions” with a wave of his hand (Figure 3).Footnote 74

The third tactic was prominently showcased during the inauguration ceremony. After the shah and his distinguished guests were seated on the stage in Shahyad Square, Gholamreza Nikpey, the mayor of Tehran, delivered a speech – in which he positioned himself as the representative of the residents of Tehran – in homage to the shah. Nikpey praised the shah for commemorating Iran’s monarchical history on its 2,500th anniversary, declaring 1971 as a “sumptuous year, named after Cyrus the Great, for the glorious history of twenty-five centuries of Iran’s independence and Iranian contributions to human civilization and culture.”Footnote 75

As part of the ceremony, Nikpey presented the shah with a golden plaque. On one side, the principles of the White Revolution were embossed, symbolizing the shah’s transformative reforms. The reverse side bore the following inscription:

This is God’s will that the sumptuous celebration of the 2,500th anniversary of the founding of the Iranian Empire occurs in the glorious reign of Shahanshah Aryamehr, who has executed the twelve principles of the Shah and People Revolution [the White Revolution] and laid the foundations for a bright era of Iran’s grandeur and prosperity.Footnote 76

The Shah had personally approved the plaque’s design and further instructed it be installed in the Shahyad Museum of Iranian History.Footnote 77

A second type of plaque bore the principles of the White Revolution on one side and featured the so-called “Cyrus charter,” which referred to the text of the Cyrus Cylinder, on the other side. In a study on a Cyrus Cylinder replica and display, John Simpson quotes Paul Gotch, the director of the British Council Regional Centre in Shiraz between 1959–1966, who had been consulted for the replica, that 160 plaques had been manufactured, “one for each of the 160 cities, towns and ports of Iran.”Footnote 78 These artifacts aimed to draw a parallel between the shah, his White Revolution, and Cyrus’s purportedly bloodless liberation of Babylon. This connection was designed to elevate the shah’s path to modernity by framing it within the context of Iran’s ancient history. Implicit in this endeavor was the assertion of Iranian gratitude, as evidenced by their contributions to the celebration in support of the Iranian monarchy.

There are indications of a third type of plaque, one that explicitly showcased the Shahyad funding model. According to Amanat, a plaque listing the name of the donors was supposed to be installed on the exterior of one of the monument’s legs.Footnote 79 This plan is further corroborated by a 1971 report, which confirms the intent to prominently display the names of the donors as a testament to their contributions.Footnote 80 However, it remains unclear whether this plaque was ever constructed or installed. If it was, it would likely have been removed following the 1979 revolution, as no such commemorative plaque currently exists on the monument. Yet, there is no recorded evidence of its removal, leaving the question of whether it was ever realized – or more broadly, whether the donors’ names were ever officially recorded – as an intriguing subject for further investigation.

Finally, returning to the inauguration ceremony, donors were prominently invited to the event and strategically showcased to the press and world leaders. Their inclusion in such a significant position was likely informed by the celebration’s extensive global outreach. Nearly 1,600 journalists, reporters, and photographers attended, ensuring coverage in 82 countries and 33 different languages.Footnote 81 The live broadcast extended the event’s reach to an audience of nearly one billion people – 27% of the world’s population.Footnote 82 Heads of state and representatives from 48 nations attended the event, with delegates from 68 countries participating overall.Footnote 83 While nearly half of these foreign dignitaries left after the first segment in Persepolis, the Tehran portion still drew an unprecedented global audience. This ensured that the peculiar group of donors, seated among world leaders, received extraordinary visibility. By integrating the donors into the inauguration ceremony, the celebration effectively maximized their exposure and amplified their symbolic significance.

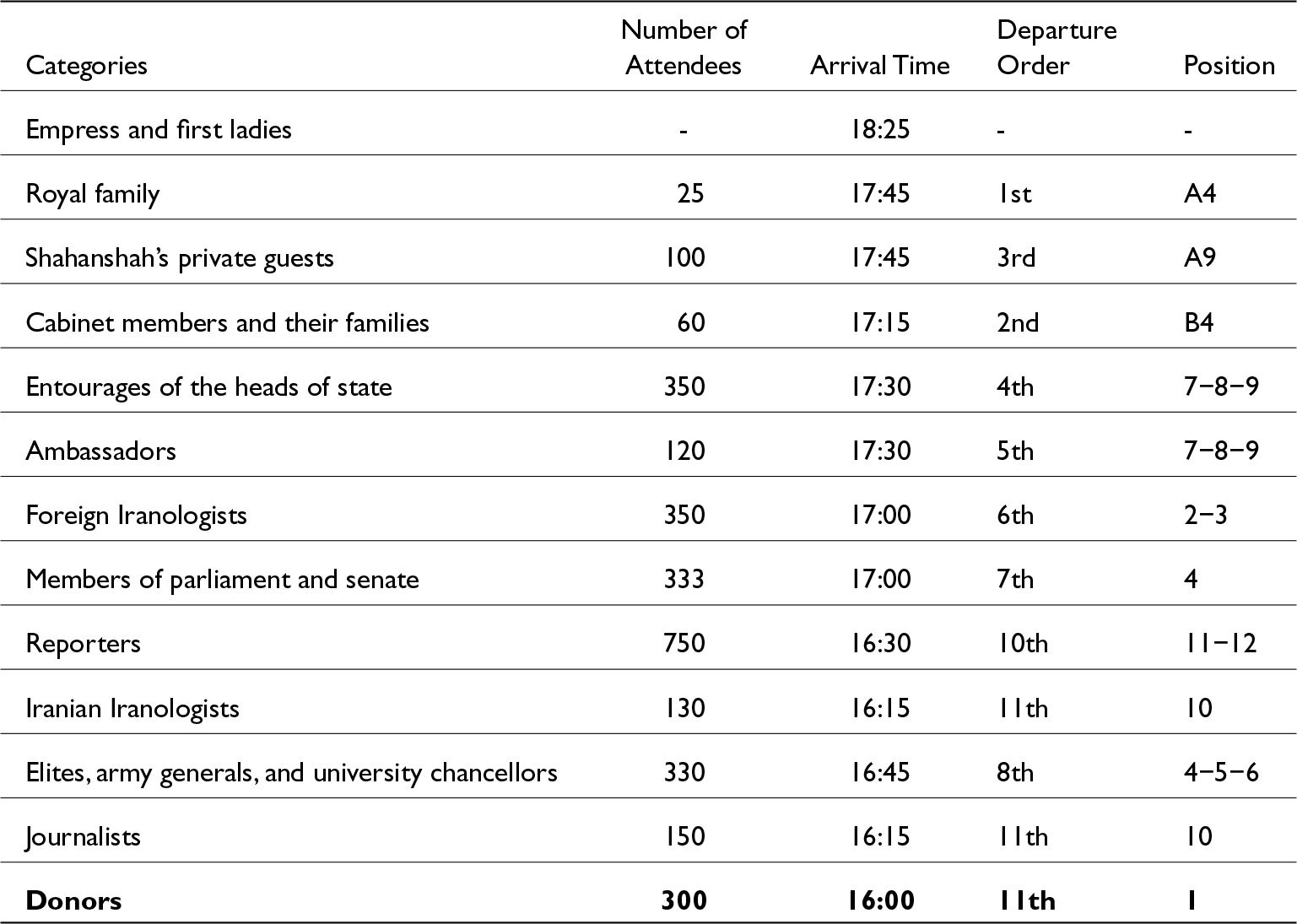

The celebration’s organizers meticulously enhanced the donors’ visibility during the inauguration by categorizing guests into twelve distinct groups. These groups included the Iranian royal family, military personnel, journalists and reporters, members of parliament and their families, cabinet members and their families, and the Shahyad funders. Among the funders and their families, 300 individuals attended the event. The organizers developed a highly detailed plan outlining seating arrangements and the timings of each group’s entry to and departure from Shahyad Square (Table 1). According to the plan, donors were strategically designated to arrive first, occupy the most prominent seating positions, and depart last. This deliberate arrangement ensured that the donors received heightened visual prominence throughout the ceremony, underscoring the political message that Iranians – particularly industrialists who arose as beneficiaries of the shah’s White Revolution – actively supported Iranian modernity and the shah’s leadership.

Table 1. Choreography of the Shahyad inaugurationFootnote 85

The celebration’s organizers meticulously enhanced the exposure of the Shahyad donors by carefully categorizing the guests into thirteen groups, including the Iranian royal family, personnel from the royal army, journalists and reporters, members of parliament and their families, cabinet members and their families, and Shahyad’s funders. Among the funders and their families, 300 representatives attended the inauguration. To maximise their visibility, the organisers devised a detailed plan for seating arrangements, the timing of each group’s entry, and the sequence of their departure from Shahyad Square (Table 1). According to the plan, donors were scheduled to arrive first—at 16:00, two hours before the official start of the inauguration ceremony—occupy one of the most prominent seating positions, and leave last.Footnote 84 This arrangement was deliberately orchestrated to grant the donors heightened visual prominence, reinforcing the political messaging that Iranian modernity and the Shah’s leadership were supported by Iranians, particularly by the industrialists who had emerged as beneficiaries of the Shah’s White Revolution.

Conclusion

The 1971 Imperial Celebration at Persepolis and Tehran is often regarded as a pivotal event in the final years of the Pahlavi monarchy. It marked a high point in the shah’s reign – “the high point of a Shakespearean tragedy that would ultimately culminate in a great downfall” – while simultaneously showcasing the peak of his international standing, “when heads of state from around the world flocked to Persepolis to pay tribute to him.”Footnote 86 Amid the ideological struggles of the Cold War, when progress and modernity were often framed through the lens of capitalism or communism, the celebration attempted to argue for a unique path: a modernizing revolutionary monarch who championed social change and delivered “striking progress” within the framework of absolutism and a monarchic institution. The Shahyad funding model, in this context, was designed to project the much-needed perception of widespread support for the shah’s modernization efforts under the White Revolution. Iranian heritage was redefined through this narrative, with the celebration contrasting the Shahyad funding model – purportedly grassroots and voluntary – with the top-down, government-funded monuments of capitalist and communist nations. Shahyad was thus positioned as a symbol of Iranian exceptionalism, purportedly reflecting progress and satisfaction among its citizens.

In the global history of art and architectural patronage, the Shahyad monument stands as a distinct case. While patronage often reflects patrons’ values and enhances their prestige, Shahyad was conceived as a large-scale public monument located at a major urban intersection, with its design, location, purpose, and rhetoric dictated by the government rather than its funders. Historically, such monumental patronage is typically associated with religious or educational institutions, where benefactors could derive spiritual or societal credit. The Shahyad donors, on the other hand, had no influence over its practical, aesthetic, or symbolic features, making the monument a divergence from conventional models of architectural patronage.

The voluntariness of the donations is another area of contention, with evidence suggesting parallels to the broader context of Iranian philanthropy, such as coerced participation in the Persepolis Forest project. Regardless of the authenticity of the donations, the celebration used architecture as material culture to amplify the narrative that the generosity of Iranian industrialists and merchants reflected the success of the shah’s path to modernity. This was achieved through four key tactics: the persistent proclamation that the Shahyad monument was funded by Iranian donors as a symbol of their gratitude for the White Revolution; a visual campaign that positioned Shahyad as a representation of Iran’s progress and industrialization, repeatedly highlighting its funding model; the creation of plaques linking the monument to the principles of the White Revolution; and giving donors prominent placement during the inauguration ceremony, positioning them behind heads of state and delegates, and choreographing their presence in order to maximize impact on domestic and international audiences.

This study provides a novel perspective on the Shahyad funding model, yet several questions remain unanswered. Despite extensive archival and print media research, none of the Shahyad monument’s donors’ names could be found, in contrast to the extensive documentation of donors for other projects, such as the Persepolis Forest and commemorative schools. Despite their prominent location during the inauguration ceremony, the absence of donor details warrants further investigation. If confirmed, it raises an important question: why did the monarchy portray the donors as an anonymous consortium of grateful industrialists and merchants rather than naming specific individuals? One plausible explanation is that revealing the donors’ identities – likely comprising public entities or Pahlavi-affiliated individuals who contributed the majority of funds, with only a modest portion from others – might have undermined the narrative of widespread voluntary support.

The main contribution of this research lies in its exploration of what “voluntary philanthropy” meant in the context of the celebration during the 1960s and 1970s, why projecting public participation and philanthropy was critical to the celebration’s domestic and international agenda, and how architecture was used to amplify and disseminate this message. The Shahyad funding model was meant to symbolize the shah’s popularity and the White Revolution’s reception; however, the contradictions between the propagated narrative and underlying reality embedded in the funding model ultimately foreshadowed the monarchy’s decline. Within eight years of the celebration, a popular uprising would culminate in the shah’s overthrow in 1979.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Financial Support

This research received no specific grant funding froorm any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.