National laws or regulations, collective agreements or arbitration awards may authorise the partial payment of wages in the form of allowances in kind in industries or occupations in which payment in the form of such allowances is customary or desirable because of the nature of the industry or occupation concerned; the payment of wages in the form of liquor of high alcoholic content or of noxious drugs shall not be permitted in any circumstances.

ILO Protection of Wages Convention, 1949 (No. 95), Article 4.1.Benefits in kind are non-cash, though they do hold monetary value. The variety of benefits considered “fringe” is huge – almost any perk you can conceive of is a benefit in kind. […] When deciding which perks to offer, consider what matters most to your workforce. If your workforce commutes to an on-site location, employees will likely value transit- and parking-related benefits. On the other hand, an entirely remote workforce will gain more from benefits like home office upgrade stipends or internet reimbursements.Footnote 1

We know hardly anything about the development of wages in kind during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote 2

Introduction

In-kind wages are today considered a remnant of archaic labour relations, an instrument for employers to transfer surplus to workers in ways that maximize employers’ own benefit. Many countries limit in-kind wages as a component of total wages, or forbid them outright as part of the minimum wage. The International Labour Organization (ILO) recommends regulating in-kind wages, beginning with the establishment of thresholds. According to the System of National Accounts (which provides international recommendations for measuring economic activity): “Income in kind may bring less satisfaction than income in cash because employees are not free to choose how to spend it. Some of the goods or services provided to employees may be of a type or quality which the employee would not normally buy.”Footnote 3

In standard economics, the dominant view appears to be that in-kind wages will disappear from the countryside as agriculture becomes integrated into a market economy. Money wages are, after all, in many ways more efficient, particularly in saving on transaction costs. Yet, even where agriculture is fully commercialized, workers often continue to receive part of their wage packages in kind.Footnote 4

Despite economists’ belief that in-kind wages persist as a mere remnant of older and obsolete labour regimens – and despite international agencies’ negative view of them – in-kind wages continue to play a fundamental role in labour's remuneration in developing economies. Such wages, however, do not exist only in developing economies. Practically all workers in industrial economies receive non-monetary components as part of their wage packages,Footnote 5 and some non-monetary benefits are particularly important to the most highly paid executives of modern corporations.Footnote 6

Recent economic literature has not only begun to recognize the continued importance of in-kind (or non-monetary) wages, but also to revise the standard interpretation of such wages. Looking at the ILO's criticism of the “exploitative” truck system in industrializing Britain – an arrangement in which workers received wage advances in the form of cash and company store goods – Tan has argued that “truck did not reduce British wages by as much as is believed, and that employers’ ability to earn rents from hiring was limited. Company store premiums are interpreted as the cost of employer credit, and workers benefited from truck because most of the time independent credit cost at least as much. Firms earned rents from riskless loans to employees and avoided holdup by independent outlets at minimal transaction costs. The British truck system was mutually beneficial, and the evidence does not support the call to abolish similar practices today.”Footnote 7 Economists have proposed a number of reasons why employers might prefer payments in kind: economies of scale and scope, which allow an employer to supply goods and services at costs lower than their market price; insufficient supply of coinage, which prevents full payment in cash; a desire to ensure that labour requirements are met, since in-kind provisions can make workers more dependent on their employers; surpluses of unsold stock; and even a need to make sure nutritional levels of seasonal workers are sufficient for them to provide efficient labour.

Explanations of in-kind payments generally depend on the analyst's school of thought. Marxians argue that such payments are exploitative, imposed by employers to the detriment of workers’ economic well-being. Standard explanations of Britain's truck system and Mexico's tiendas de raya are examples of this viewpoint. Mainstream economists tend to argue that market forces will gradually drive in-kind payments, inherently inefficient, from the economy. In a modern economy, neither employers nor workers should favour such payments; however, during a period of high inflation or price instability, the two groups’ interests may diverge. In a high-inflation period, for example, employers would want to maintain cash wages, which are increasingly devalued, while workers would push for relief in the form of in-kind payments. Wages of US industrial workers in the nineteenth century have been explained this way. A third perspective is put forward by labour economists and industrial organization theorists, who have posited that in-kind payments can be an important component of so-called efficiency wages, whereby employers design payment packages to recruit and retain skilled workers.

Finally, economic historians see in-kind payments as substandard and thus only accepted by workers with little bargaining power, such as women and informal workers. An important vein of economic history literature on wage labour in early modern Europe develops the idea that insufficient supply of coinage was the factor accounting for in-kind payments. The spread of money wages is explained by the increase in the money supply made possible by the influx of precious metals from America.Footnote 8 The question of money supply has rightly forced labour historians to think in global and financial terms. However, this argument has ended up identifying monetization with economic modernization, something that does not correspond to historical evidence.Footnote 9

In this article, I analyse how in-kind wages functioned in certain historical contexts, and conclude that these explanations are far too limited.Footnote 10 The economic literature has barely looked at in-kind wages from the workers’ point of view. When the focus is shifted to workers’ perspectives, it becomes clear that they had significant agency in the construction of the social bargain underlying wage formation. For example, in-kind wages in the form of room and board were often the main reason for workers, particularly young women, to enter occupations where such payments were common, such as domestic service. Workers’ views and strategies regarding in-kind payments depended on their individual and familial needs within the broader economic circumstances.Footnote 11

Historical analysis of in-kind wages usually centres on calculations of the wages’ market value. Yet, understanding in-kind payments as a simple equivalent of money wages (a different form of the money wage) overlooks the fact that commodities could provide workers with important options. In-kind payments were different from money. Analysing them helps us understand not only wage levels, but also wage work, labour supply and demand, wage differentials, and workers’ welfare. In many situations, workers sought to be paid – totally or partially – with commodities, and their reasons were not always the same. Here, I discuss different types of in-kind payments, the different roles such payments played, and how they provided workers with opportunities to improve their economic welfare or, in dire circumstances, to survive.

Monetary wages were well established across Europe before the eighteenth century, but their share of total wages depended largely on workers’ occupations. In eighteenth-century Spain, construction labourers and other city craftsmen were paid entirely in cash, as were external wet nurses and other employees of foundling hospitals and other charity institutions, as well as civil servants.Footnote 12 Shepherds and farm servants were paid wage packages that included money and commodity components, usually grain. Doctors and rural teachers received similar packages. Domestic servants, particularly women domestics, might be paid entirely in kind.Footnote 13In-kind wages are difficult to trace. Primary sources are usually silent, or vague, about them, which explains why farming accounts are regarded as problematic by historians.Footnote 14 Indeed, one of the main reasons why most historical wage series focus almost exclusively on the building trades is the difficulty in identifying and assigning monetary value to in-kind wages, which were common in other, often rural occupations.Footnote 15 But the very vagueness of these first-hand accounts suggests that in-kind payments were a normal part of life and thus taken for granted – more common than we think. Here, I use two sources that did record the value and the composition of in-kind payments. First, I look at early nineteenth-century newspaper advertisements in Madrid, which reveal important aspects of the city's labour market (although those placing the ads could be from anywhere in Spain, or even from France or other European countries). Next, I look at household declarations for the mid-eighteenth-century Ensenada cadastre, a document that was prepared for purposes of tax collection and which covered much of Spain's interior region. In addition to empirical evidence from these two sources, I present supporting material on in-kind wages from elsewhere in eighteenth-century Spain and refer to case studies from around the world, both in developed and developing economies.

“Taking Care of the Critical Circumstances of the Day”: Seeking Domestic Servant Jobs in Bonaparte's Madrid (1808–1812)

On 2 May 1808, the population of Madrid took up arms against the French army, which had invaded the country. The Madrid uprising was crushed, and, across Spain, the French army punished local populations’ lack of cooperation, acts of sabotage, and guerrilla activity. War would rage until 1814. Towns were sacked; fields were destroyed. By 1812, crop and cattle losses were greatly exacerbating the disruption to trade and farming already caused by years of deployment of the English, French, and Spanish armies across the Iberian Peninsula. Grain production plummeted, food became scarce, and people starved (Figure 1). Dantean scenes occurred in the streets of Madrid, where hundreds of cadavers were collected in carts each day.Footnote 16

Figure 1. “El Hambre de 1811” by Carlos Múgica y Pérez.

Source: Digital Library Memory of Madrid, Spain – CC BY-NC. https://www.europeana.eu/item/2022711/11931

Madrid had a population of about 190,000 at the beginning of the century. In December 1811, after three years of war, Madrid's official commission of public assistance estimated the number of poor at 10,000, with 3,000 or more “in the most urgent and absolute indigence” (Diario de Madrid, 3 December 1811). The city government's response was to expel them to their hometowns.Footnote 17 The newspaper Diario de Madrid recorded “the disasters of war” with news about the plundering and deaths caused by the French and English armies. Once the French had settled into the capital, the paper began publishing a range of notices and articles that chronicled the difficult circumstances: government decrees imposing extraordinary taxes on the population, exemplary stories of bandits put to death for attacking French soldiers or for robbing muleteers, and lists of the purged and the appointed. The economic crisis made its way into the paper's pages with countless ads placed by people selling their carriages, dish services, paintings, musical instruments, jewels, and beds. Recipes for making bread from potatoes appeared on 16 January 1812. Perhaps most tellingly, the economic hardship suffered by Madrid's citizens was revealed in the many ads posted for room rentals.

These rooming advertisements in Diario de Madrid show the strategies developed by different social groups to cope with the crisis. For example, while members of the middle and upper classes sought women or men to share their apartments “to help pay for the board”, workers or widowed women asked for jobs as servants, with room and board as the payment. I have analysed the advertisements in the “Servants” section of Diario in 1808, 1811, and 1812.Footnote 18 These advertisements allow me to identify workers’ strategies for coping with the crisis – and how such strategies evolved as the crisis worsened. Workers’ first reaction was to reduce the amount of monetary wages they asked for.Footnote 19 After a few months, however, advertisements asking for money wages began to disappear, and the objective of most ads became the quest for lodging to avoid paying rent. The need for housing becomes the primary determinant of labour supply. At the same time, the boundaries of wage work blur, and defining who is employed becomes increasingly difficult. In an attempt to avoid losing their apartments, men and women – but particularly the latter – who formerly were not employed, now offered their services as domestics to those who could move in and help pay rent.

A decent woman […] wants to find a gentleman to help pay her room, likewise giving him assistance if to his convenience. (16 April 1811)

Any gentleman who could manage the food in a decent house with an arrangement to his convenience will be attended with the greatest attention. (24 April 1811)

Two decent women […] want to find a gentleman to help pay board and live in their company. (25 April 1811)

Sometimes, the job seeker identifies options: a widow offers to “serve a man or married couple”, but if she “finds such a single man or married couple for her house, they will be taken in as renters” (1 May 1811). The supply of such servants seems almost endless; advertisements offering to work solely for room – and, increasingly, board – appear almost daily. Below are examples of women, men, and couples who explicitly forgo charging a monetary wage.

An individual who has pursued and finished a literary degree, and who has studied the management of papers and other things, wants to get himself a job as butler, representative, or other decent destiny, even if only for food and room. (29 August 1808)

A woman of means, well instructed in the management of a house and in all types of sewing, wants to find a job with one or two women or gentlemen, advising that she only requires a bed. (21 July 1811)

A couple without children wants to find a position just for subsistence in a decent house, the woman knows [matters] pertaining to running a house and the husband [how] to write and count fairly well. (5 September 1811)

An individual who has been employed in one of the old offices, and whose handwriting was worthy of high approval for its form and speed, wishes to employ himself with a person who will give him work in order to subsist. He will also work as a kind of butler, and will go outside of Madrid if so provided, or he will work in the house of a business gentleman solely for upkeep. (21 November 1811)

An honourable couple, of young age, who has those who will vouch for their conduct, wants to get a job in a decent house, or will assist some official men just for upkeep; the husband will write, clean clothes, and shop; and the women will mend clothes, iron and do the rest of the domestic chores. (14 April 1812)

A woman who knows how to make thread laces, gold and silver doilies of all qualities, long and medium gloves, wants to find some young women to whom she can give classes in this training; and who will at the same time serve for the rest of the household chores only for subsistence. (17 May 1812)

An individual of distinction, neighbour of this court, of 46 years, who is instructed in the management of papers, wishes to find work within or outside of Madrid without stipend other than daily food; advising that he will handle without difficulty anything offered in the house, and even will go shopping. (15 August 1812)

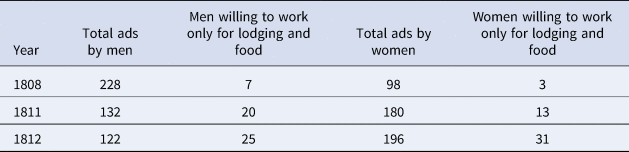

Table 1 shows the number of advertisements by people seeking work as servants who specify that they will work just for food and lodging.

Table 1. Madrid individuals seeking jobs as domestic servants and willing to work only for lodging and food.

Note that, in 1808, the paper was not published for part of May, all of June and July, and the first week of August. The total number of advertisements is approximate, as they rarely include names, and it is thus not always possible to detect repetitions.

Source: Diario de Madrid.

To these numbers must be added those of women looking for work as wet nurses – an average of twenty-five every month – many of whom aimed to work in the house of the baby's parents, that is, receiving board and lodging as part of their wages.Footnote 20

Most of the people posting advertisements hoped to be remunerated with lodging and food; however, in a few cases, posters mentioned another need: lumbre y luz, that is, fuel for “hearth and light”, or even shoes.Footnote 21

Food and accommodation had become so scarce that domestic service attracted individuals who otherwise would have remained outside this labour market, either by living from rent (particularly single women and widows) or, in the case of men, continuing their studies or maintaining their jobs in private business or as civil servants. Posters were moving into the domestic service sector in search of food and lodging. They did not want money to be part of the work exchange.

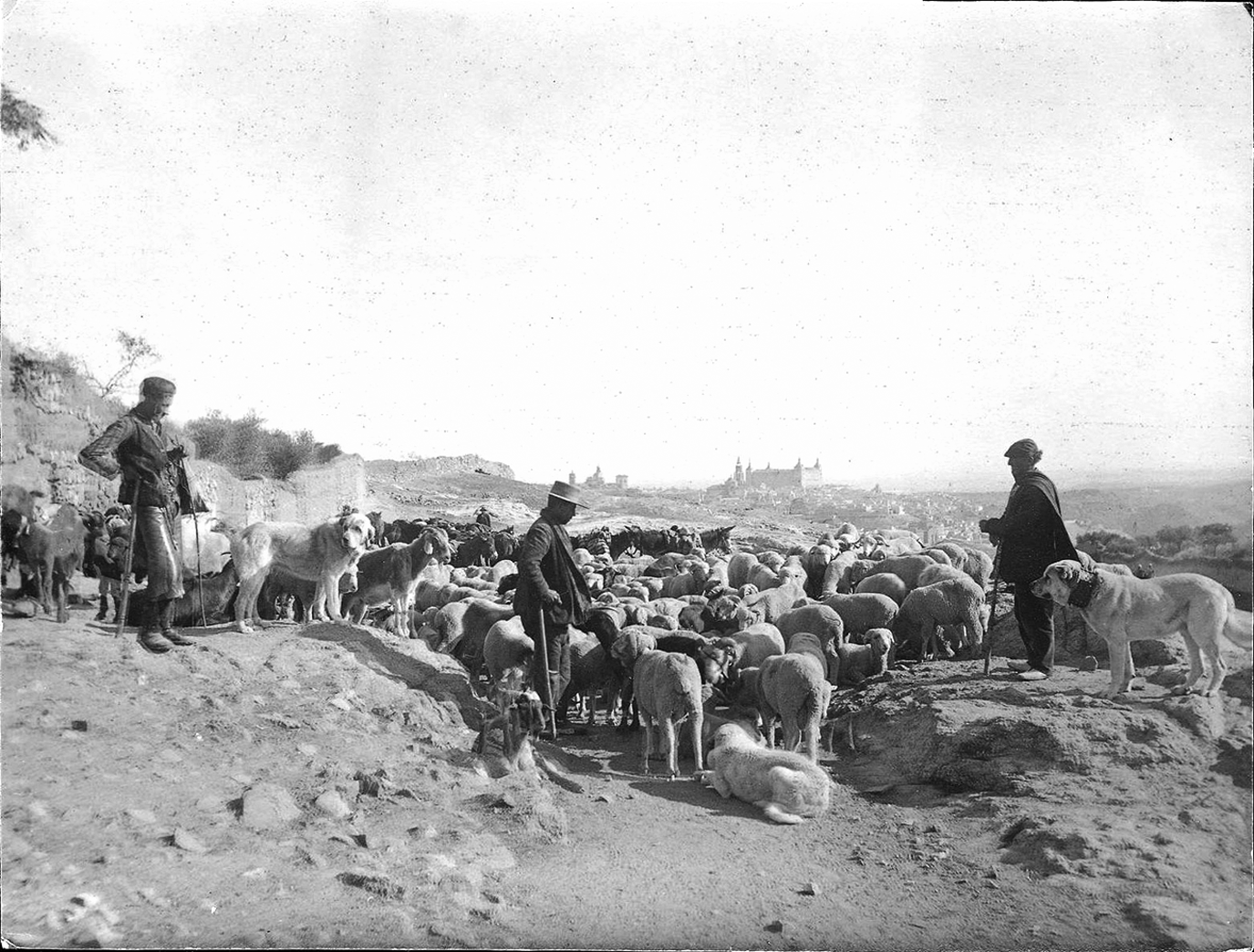

Table 2 shows the effects of the war on prices and wages in Madrid and Castile. From 1810 to 1811, prices more than doubled, and, as would be expected, the value of wages collapsed. For Madrid's citizens, and especially its wage earners, the situation only worsened the following year. Prices climbed another sixty-one per cent, while real wages fell another thirty-four per cent. Compared to the first year of the occupation, inflation had pushed prices up more than 250 per cent, while those lucky enough to still have jobs had seen the value of their wages fall by almost seventy per cent.

Table 2. Index of prices, wages, and real wages, Madrid and Castile 1806–1815 (base: 1790–1799).

Source: David Reher and Esmeralda Ballesteros, “Precios y salarios en Castilla la Nueva. La construcción de un índice de salarios reales 1501–1991”, Revista de Historia Económica, 11:1 (1993), pp. 101–151, 134.

In-kind wages were vital to protect workers from poverty, and not just in the dramatic circumstances of Madrid and Spain in 1811 and 1812. In seventeenth-century Toledo, “payments in kind far exceeded subsistence requirements and played an important role in shielding workers’ earnings from inflation”.Footnote 22 In rural Navarra, in the context of the subsistence crisis of 1804: “Between 1789 and 1805, as agricultural day workers saw their purchasing capacity deteriorate, rural servants experienced the opposite tendency, thanks to the presence in their remuneration of an in-kind component, of mostly wheat, in an inflationary context.” Footnote 23

Such historical evidence is consistent with what economists find today in developing agricultural economies. Studying in-kind wages paid to agricultural workers in Asia, Kurosaki concludes that, in the initial phase of economic development, “when food security considerations are important for workers, owing to poverty and thin food markets, they tend to work more under contracts where wages are paid in kind (food) than under contracts where wages are paid in cash […] [I]n-kind wages can enhance the food security of rural households faced with thin food markets and missing insurance markets”.Footnote 24

With in-kind payments, the worker takes on the risk, but also enjoys the rewards resulting from fluctuations in the value of goods. Hence in-kind payments seem to have been particularly important for workers in periods of inflation, when monetary wages rapidly lost their value in real terms.

In-Kind Wages that Allowed Certain Workers to Climb the Economic Ladder

In a different set of historical circumstances, in-kind wages played a very different role. Rather than protection against the impact of rising prices, commodity payments were sought by workers as a mechanism to accumulate assets and move up the social ladder. In this case, shepherds and farm servants negotiated wage agreements that allowed them to gain access to goods they could save and trade for profit.

By the mid-eighteenth century, Spain's sheep herd had grown to about 24 million head, the largest it had been since the Middle Ages. The biggest flocks belonged to nobility, monastic orders, and rich merchants, who sold wool for export to Europe and to manufactures in Spain. Environmental conditions required a vast system of seasonal migration. Each year in late spring, animals were moved to northern valleys in search of green pasture, where they would remain until October, when they were moved back to southern fields. This movement of livestock shaped the occupational structure of La Mancha, a plateau region where transhumant pastoralism predominated.

Using the declarations of household heads to officials of the Ensenada Cadastre, a database has been built for workers in La Mancha in the mid-eighteenth century.Footnote 25 The database comprises 44,484 individuals who lived in twenty-two localities – from tiny villages to cities – in five provinces of this southern region. There are 761 shepherds in the database, accounting for 9.6 per cent of those occupied in the primary sector. In some towns, sheepherding was particularly important. For example, El Carpio had 104 shepherds, or 30.4 per cent of the men in the primary sector.

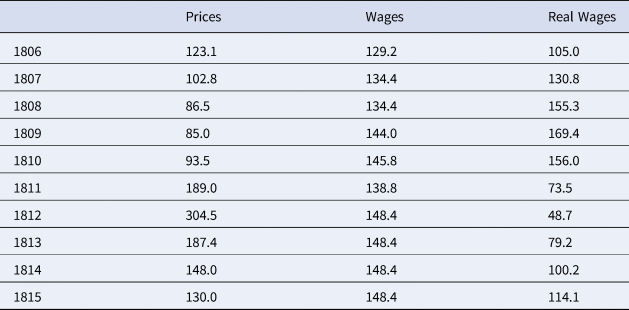

An owner's herd would be divided into flocks of about 1,000 sheep. Shepherds worked in teams, with mayorales, or head shepherds, hiring their sons and male relatives to accompany the flocks. The men typically worked in groups of five: the rabadán, who worked under the direct orders of the mayoral; a “companion” or “second”; an “extra”; a “helper”; and, finally, a zagal, a boy to take care of the shepherds’ hut, dogs, and pack animals (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Shepherds near the city of Toledo, around 1900.

Source: Fund Photographer Pedro Román. Digital Library of the Diputación de Toledo. https://bibliotecadigital.diputoledo.es/pandora/results.vm?q=parent%3A0000049699&s=345&t=-alpha&lang=es&view=fotografias

Wage agreements between owners and shepherds were negotiated around Saint Michael's Day (29 September) and would expire the following year on Saint John's Day (24 June). One of the main matters that had to be agreed upon was the escusa – the number of sheep belonging to the shepherd that the master would allow to join his herd, grazing the same grasses but without paying rent. This in-kind remuneration was advantageous to the owner, since it ensured that his sheep would be treated well. He could be confident that his animals would not be moved excessive distances on any one day, that they would be provided with sufficient water and food, and that they would be protected from wolves and other animals. Allowing shepherds to run their own sheep in owners’ herds was a powerful incentive to give the animals the best possible care. For shepherds, the deal constituted a double in-kind payment. First, they were paid with sheep, and second, their sheep's forage was on the owner's books, since it was the owner who paid rent for the pastures where the animals grazed. A further sweetener was that the work of taking care of their own sheep became practically free.

In economic terms, this would be called an example of “incentive wages”, and is somewhat akin to sharecropping. Sharecropping is usually defended as a way to balance two competing goals: creating incentives for work while spreading the risks of lean years (as well as the gains of fat years). Since sharecroppers are paid according to their harvest, they are encouraged to work long and hard. But when crops decline or fail, their payments fall proportionally, and so owners will share at least some of the cost.Footnote 26 Incentive wages thus ensure a higher quality of produced goods.

The men working the herds were not the only ones to have sheep in the owner's flock. Farm servants could also have a few head in the flock, and would so benefit from the care of the collective group, or guarda. If they were not charged for the benefit, it, too, constituted a form of in-kind payment. For example, Miguel Peña, a twenty-five-year-old farm servant in Alcaraz, states that he was paid with money (24 ducados each year) and a fanega de peujar, a small plot of land.Footnote 27 But he also had “a cow and two hogs in guarda in my master's herds for which I don't pay anything for the guarda”. In the same locality, Pedro Fernández, a forty-one-year-old day labourer, had a different arrangement with his master: “three goats in guarda and for them I pay three and half reales per head each year” [subject #989]. Supposing that the guarda of cows, goats, and hogs in a master's herd had the same annual cost, we can thus calculate that the farm servant Miguel Peña, who was allowed to keep his animals with the master's herd for free, was, in addition to his monetary and land payments, receiving roughly the equivalent of 10.5 reales in kind annually, or a total of 274.5 (264 reales in money plus 10.5) plus the small plot of land. Footnote 28

In Villarejo de Salvanés, a town with 2,055 residents, Cristóbal García, a fifty-year-old shepherd in the service of Don Juan de Monterroso, earned wages of 950 reales “together with his sons” (Rafael, 21; José, 16; and Matías, 12) plus “20 head free of care and pasture”. In addition, he states that he owned ninety-three sheep, of which sixty-one are “given in rent”, which means they were grazing with the herd of another sheep owner, to whom he pays rent. Cristóbal was a wage worker, but he was using his and his sons’ income – in particular the in-kind part of it – to accumulate sheep. He is a shepherd and a sheep owner at the same time. Across the region, shepherds follow the same accumulation strategy. Alonso Fernández, forty years of age, the mayoral of El Carpio, earns 350 reales and fifty head per year. The fifty sheep were worth 500 reales, so almost sixty per cent of Alonso's annual income was in kind. He states that he also owned thirty-six sheep and nine rams, as well as a house, an olive orchard, and other land. In the same locality, shepherd Matías Hidalgo, thirty-seven years of age, earned 250 reales and fifteen sheep annually, while owning 120 sheep, a female donkey, and a female pig.

Weight of In-Kind Wages within Workers’ Total Remuneration

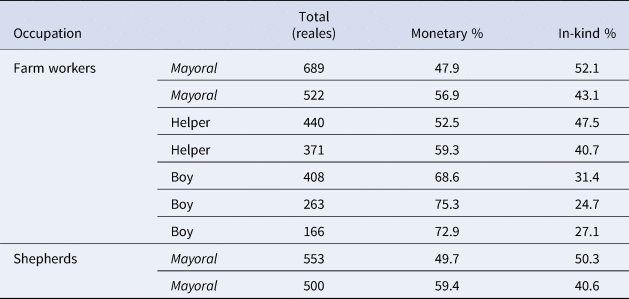

An important question is the weight of in-kind payments within workers’ total remuneration packages. For servants in Madrid during the Napoleonic army's occupation, in-kind wages – mostly food and lodging – were one hundred per cent of their total wages. For shepherds in La Mancha, the picture is somewhat more complicated. The Ensenada Cadastre was an official tax survey requiring household heads to declare their income for the entire domestic unit, so, with a few extra steps, it is possible to determine individuals’ total wages. In some localities, householders simply assigned a monetary value to the in-kind goods received rather than identifying the kinds of goods, their amount, or their quality. In other localities, householders stated the exact composition of their wage packages, including the monetary and non-monetary parts. Table 3 shows the composition of wages of farm servants and shepherds in a locality where data were particularly well recorded, the town of Pedro Muñoz (in the present-day province of Ciudad Real), with a population of 2,213.Footnote 29

Table 3. Wages of farm workers and shepherds in mid-eighteenth-century Pedro Muñoz.

Source: Sarasúa, “Women's Work”, 2019.

A couple of things stand out. First, in-kind remuneration made up a substantial portion of these workers’ total wages – between twenty-five and fifty-two per cent. Also, the higher the worker's position, the higher the share of in-kind payments in his total wage.

More than a century later, in 1889, a parliamentary commission was tasked with gathering information on the working and living conditions of the working class. Among other things, it collected data on in-kind wages and their weight in workers’ total income. In the province of Ávila, in Northern Castile, the commission found that the in-kind component ranged from sixty-eight to seventy-four per cent of total wages for farm servants, while for mayorales the figure was eighty-one per cent.Footnote 30 As was true in Pedro Muñoz more than a century before, the higher the position, the higher the in-kind share of wages. Senior workers, we shall see, were able to demand land and sheep as part of their wages.

In-kind wages also constituted a large part of the incomes of other occupations in Ávila during the period. For young workers (men and women) in domestic service, and for those labouring in commerce and artisan workshops, in-kind payments could be the totality of their remuneration. Miguel Estúñiga, a wealthy wax and iron merchant in the city of Guadalajara, had a maid whom he paid 14 ducados annually, a wax-maker whom he paid 40 ducados, and an apprentice whom “I do not pay any wage except food, clothing, and shoes that I set at 100 reales per year”.

For shepherds, wages could include cash, footwear (or its monetary equivalent), wool, and sheep. For example, José Meco, a married twenty-five-year-old “helper shepherd in the house of Don Antonio Granero”, stated that he was paid “24 ducados, 2 arrobas (23 kilos) of wool, 40 reales for footwear, and 15 head, which together make 424 reales”. (His employer claimed a higher monetary value for José's in-kind payments: “with wool and sheep […] 512 reales”.)

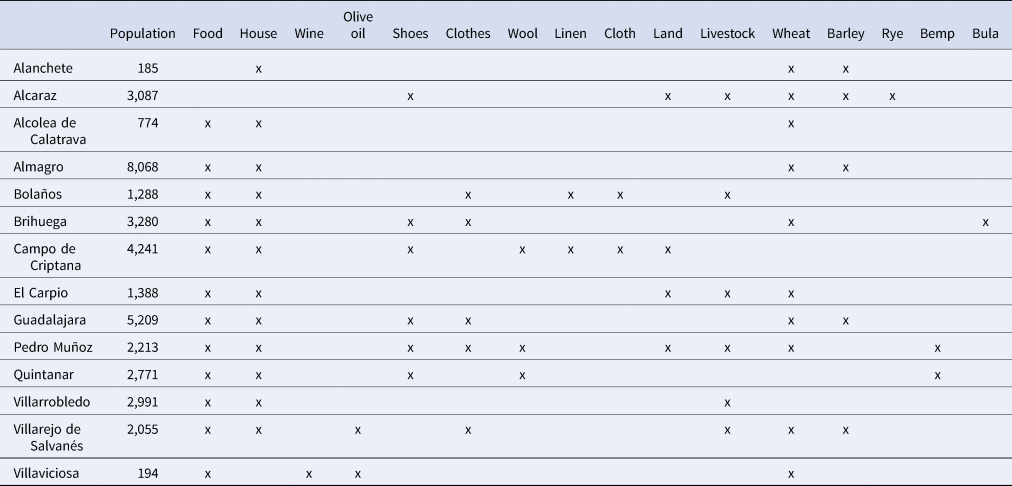

Compiled from the Ensenada Cadastre, Table 4 shows how widespread in-kind payments were in La Mancha. (The sample represents a total population of 37,744 individuals.) Also notable is the sheer variety of commodities included in wage packages. Sixteen goods show up in the Cadastre's pages. Some were consumption goods, intended to provide families with food, firewood, or clothes. Some – usually raw materials such as wool or grain – could be traded. Some, such as boots and clothing, were meant to be used at work. Finally, there were goods that we might call “means of production”, such as plots of land, orchards, and sheep.

Table 4. In-kind payments to men workers in eighteenth-century La Mancha.

Source: Sarasúa, “Women's Work”, 2019.

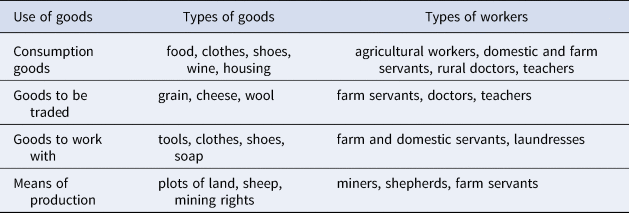

In-kind payments can thus be categorized three ways: by type of good or service; by kind of worker (who received them); and by social and economic function. Table 5 shows such a classification.

Table 5. In-kind payments: Uses, types, and workers receiving them in eighteenth-century Spain.

Source: See this article.

Consumption Goods

The most common in-kind payment was food and drink (wine) for consumption during the workday.Footnote 31 Agricultural workers, farm and domestic servants, shepherds, and, generally, all those who were away from their households and worked for a master received food as part of their wages.Footnote 32 The cost was negligible for the masters, as the food they provided was usually meagre and of poor quality, mostly consisting of surplus from their own production, such as wine, barley, or bread. If workers were out in the fields, they might be allowed to hunt a rabbit or a bird.Footnote 33

In the case of domestic servants, who were usually given leftovers from the family's table, food as in-kind payment was never declared or fixed by contract. This was an important difference between food given to women and food given to men. In men's occupations, food paid to workers was fixed by contract, and therefore declared to Cadastre officials by both workers and masters.

In the mid-eighteenth century, in what is now the province of Guadalajara, a small village was located near a Hieronymite monastery. Villaviciosa had a population of 176 (not including the twenty-two monks), most of whom were shepherds and farm helpers. The monastery owned 820 sheep and employed eight mayorales and five zagales. Each mayoral received annual pay of 730 reales. Monks explained the payment this way: “300 reales plus 430 reales for a bread of two and a half pounds and a quartillo [about 1/2 litre] of wine and one pound of fat or oil that is given to them every week for their sustenance”. The boys got 590 reales – 150 reales plus the same food and wine package that mayorales received.

One of the region's most well-paid occupations was that of sexton, an assistant in convents, monasteries, and churches. The job was lucrative in terms of in-kind wages, allowing some of these men – who were often paid for several activities, such as teaching children to read and write, helping with burials and marriages, and ringing the church bells – to accumulate important assets. The fifteen sextons in the city of Guadalajara were all paid in cash, plus “a bread of two pounds” daily. Some of them also received meat. One, Diego Bravo, forty-three, who was the sexton at the School for Discalced Carmelites as well as a carpenter, was paid in cash and “daily bread”.

“Drink”, meaning wine, was part of the wage of farm servants, though usually included as part of “food”. In fact, it is only specifically mentioned in the records of Villaviciosa and Villarejo. Wine might be considered a consumption good but it was also a “good to work with”, as it was believed to stimulate workers’ productivity and warm them during the winter.

Clothes and Footwear

Francisco Plaza, a twenty-year-old farm servant in Brihuega, who ploughed with a couple of mules, got an annual wage of “16 ducados plus two shirts and footwear as well as food”. In Bolaños, Agustín Fernández, twenty-five years of age, was employed collecting taxes for the Duke of Santisteban. He earned 14 ducados and “shirts, cloth, and linen”. Gregorio Melero, a widower, aged sixty, worked as a farm servant in Campo de Criptana, earning “16 ducados, 4 varas of cloth, 4 of linen, 3 pairs of shoes, and a fanega of fallow land”. (A vara measured 0.83 metres, so the cloth and linen he received were probably just enough to make a suit of clothes and a shirt – if he did not sell them.)

For domestic servants, clothes and shoes were a traditional form of in-kind payment. Normally, the items had been previously used by family members or were bought in a second-hand market and so were not mentioned in wage contracts. But sometimes domestic workers got new items, which were stipulated in wage agreements. For example, José Picazo, a thirty-two-year-old farm servant in Brihuega, “earns each year ten ducados, two shirts, footwear, and bulas”.Footnote 34 For young men hired as servants or apprentices, contracts included an annual payment that usually was for simple upkeep. Frequently, a suit or shirt that would be given to them at the end of the work period as an incentive not to leave early. For example, in Brihuega, Antonio de Juan, a fifteen-year-old servant, was “paid for six years giving him in the course of those years the necessary clothing and at the end of them a cloth garment from this town”. In the city of Guadalajara, the master of Santiago Fernández, an eleven-year-old apprentice shoemaker, stated that he did not pay the boy any wage “for he is paid only with food and after six years I will give him a suit”. Leather shoes and boots regularly appear as part of men's wages, and may be considered consumption goods, but also as goods to work with, particularly when they were part of shepherds’ pay packages.

Shopkeeper servants, who attended to customers, might have their clothes washed as part of their payments. For example, Juan Coca, twenty-six years of age, who worked in one of the two apothecaries of the city of Guadalajara, earned “360 reales per year as well as food and clean clothes”. In a few cases, medicine or medical services were forms of payment. Don Rodrigo Arquero was an accountant in the royal factory of Guadalajara. This fifty-year-old widower had a woman employee (who may have been his de facto wife) to whom, he stated, “I give nothing more than her food and what she needs for her recovery”.

None of these consumption goods, however, were as important as housing. Often just a room, housing was usually the key component of wage packages, and was the reason why many workers, particularly girls and immigrants, entered the domestic service sector. Housing was also important for upper-level domestic staff, who were provided with “hearth and light”. Skilled workers, such as school teachers and doctors, were often offered housing (see Table 7). Throughout the nineteenth century, Spanish localities, especially small and medium towns, set aside municipal properties for the “teacher's house” and the “doctor's house”, where these employees could reside during the years of their contracts. Members of the Guardia Civil, a military force established in 1844 to police rural areas and small towns, had housing facilities throughout the country.

Goods to Trade With

Sometimes, food was not paid in small daily or weekly amounts “for sustenance” or “upkeep”, but annually and in relatively large quantities. Three grains (wheat, barley, rye), as well as two plant fibres (hemp, flax) used in textile production and the animal fibre (wool) that was the raw material for the region's main textile production, appear in large allotments in my sample. Which products showed up in a wage package depended on the local economy. Wheat and barley were cultivated in all localities, while rye was only grown in Alcaraz. Flax could only be grown in places with abundant water, so linen only appears as a wage component in two localities of this arid region. However, linen cloth and shirts (which were always made with linen in the mid-eighteenth century) appear in several other localities as part of men's wages, indicating that owners bought them elsewhere (or paid their equivalent in money).

The grains and fibres that made up these larger annual payments were raw materials in the production of a variety of goods. Workers who received them thus had more options: the materials could be processed for consumption by the workers and their families, they could be used to pay debts, or they could be sold for profit.Footnote 35 Wool was a typical component of in-kind payments for shepherds. Campo de Criptana (whose windmills Don Quixote had confused with giants two centuries before) was an important locality with 4,241 residents. Most of the town's twenty shepherds just gave the total monetary value of their wage packages, but three elaborated on the kinds of goods that made up their wages (see Table 6). In all three cases, the wage package has the same structure: money + wool + linen + three pairs of shoes. For example, Manuel Fernández Mendibar, fifty-five years of age, earned “18 ducados, two arrobas of black wool, 27 reales of footwear and 10 reales of linen”.

Table 6. Wage composition of workers in Campo de Criptana.

Table 7. In-kind payments to women workers in eighteenth-century La Mancha.

One arroba of wool equalled 11.5 kilos, so these shepherds were receiving 17.25 to 23 kilos of wool as part of their annual remuneration. A vara of linen was about 0.8 metres, which means these men got about 3.2 metres of linen each year, enough to make two shirts. The wool and linen could be sold – or spun and woven by a woman in the family and then sold as finished products with greater added value.

Campo de Criptana's only farm servant also gave the composition of his in-kind payments, and it is different from those of the shepherds. Although he received the same three pairs of shoes and the same four varas of linen, he got his wool already woven (four varas of cloth) and, in exchange for taking somewhat less money, he received a small piece of land to cultivate. One explanation is that the wool received by shepherds came from the herds they took care of and that they could not – or did not want to – be paid with land, as it would have prevented them from practicing their migratory occupation.

Goods to Work With

Determining whether some goods were used for personal consumption or for work is difficult. Clothing and footwear are clear cases of goods that a person needed for work. Indeed, in some cases, they were indispensable. Shepherds walked an average of fifteen to twenty kilometres each day during their migratory months, so they needed good leather boots, which were part of their remuneration. Of course, they also wore boots when not working, and could eventually resell them after the season.

The Cadastre makes no mention of tools as part of workers’ wage packages, but we know from other sources that tools could be important form of payment. For instance, laundresses received soap as part of their wages.Footnote 36

Means of Production: Converting In-Kind Payments into Assets

In-kind payments in eighteenth-century La Mancha enabled some workers to accumulate assets, eventually allowing them to become small landowners or livestock owners themselves. A key factor in this process, of course, was the amount of the wage and its composition. Also important were the number of household members who pooled their wages, as well as market conditions. Granting certain workers access to means of production, thus allowing them to escape the state of “pure wage worker”, was an old incentive in many sectors.

As noted in Table 4, workers in some localities were paid with land – not in title but as a right to cultivate – or with animals. In at least four localities, wages for farm servants included small plots, usually one fanega (6,560 square metres), while in at least six localities, payments for shepherds included sheep. Sometimes, workers were paid with mares and goats. For example, Pedro Ortega, a fifty-year-old farm servant of Doña Águeda de Coca, in Alcaraz, gets an annual wage of 30 ducados and two mares. He owns thirteen goats.

This kind of wage structure was common in rural Spain until the first half of the twentieth century. According to an 1899 report produced by the Social Reforms Commission (mentioned above), in the province of Ávila, money comprised only about a quarter of the total agricultural wages.Footnote 37 In-kind payments had one or more of these parts:

• Food, including breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

• Plot of land to grow wheat or chickpeas for family consumption and for sale.

• Between 12–20 fanegas of wheat or rye, and a smaller amount of chickpeas or potatoes for planting. Shepherds, horse breeders, and cowboys received a small amount of wheat and rye for family consumption. Instead of land (as in La Mancha), their wages were supplemented with livestock: 10–16 sheep for a shepherd, three cows for a cowboy, and two mares for a horse breeder. This livestock was raised with owners’ animals.

• One or two wagons of straw to feed mules or donkeys, a blanket, and shoes.

Such annual payments apparently served as means for workers to accumulate assets. José Lucero, a forty-six-year-old sheep mayoral in El Carpio, declares an annual wage of 340 reales and thirty-seven head “free of cost”. He has three sons (21, 19, and 16 years of age), all shepherds in nearby localities, who earned only money wages (26, 24, and 15 ducados, respectively). José owned fifty sheep, three goats, and a donkey, in addition to two houses, one of which was rented out. In the same town, Francisco Hidalgo, a forty-four-year-old sheep mayoral, earned 30 ducados and fifty head each year. He had a nineteen-year-old son, also a shepherd; a house; sixty-eight sheep; and a donkey. Alonso Fernández, forty years of age, was a mayoral who earned 350 reales and fifty head. Alonso owned a house, an olive orchard, a hawthorn patch, thirty-six sheep, and nine rams. All of these shepherds were wage-earning mayorales who, largely because they could demand part of their wage in kind, had become small livestock owners.

For shepherds and farm servants, such access to land and livestock was not exceptional. On the contrary, across Europe, at least until the middle of the last century, the agrarian proletariat who lived solely on wages was relatively uncommon. Food, housing, and other benefits were often more important than monetary remuneration to farm servants.

Land in wage packages did not always enable workers to accumulate wealth. In Almadén, where mercury had been extracted since the fifteenth century and which was one of Europe's most important mining areas, in-kind payments were a widespread practice.Footnote 38 The mining labour force was divided between company employees and miners. Many employees received wheat, barley, candles, and firewood, plus, for those of higher rank, a house. Miners’ pay included tax and military exemptions, medical assistance, pensions to widows and orphans, regular allotments of bread and wheat, and an annual distribution of a small plot of land or garden orchard. In this case, the land was not a means for accumulation. Rather, it was a way for owners to keep miners in the region – as a kind of agricultural labour force – during periods when the mines were closed. Seasonal orchard work helped miners sustain their families (while unintentionally lowering their risk of developing silicosis).Footnote 39

In-Kind Wages Paid to Women Workers

In-kind wages are often viewed as more characteristic of women's wages than of men's. As Jane Humphries and Jacob Weisdorf have argued for modern England: “Women were more likely paid as part of a team, by task or in kind. Day wages, where they exist, are hard to compare with longer term contracts which usually involved a significant element of board and lodging.”Footnote 40 Similarly, Robert Allen writes: “While women and children have often worked, they have rarely been paid with a daily cash wage. Often they have been paid according to a piece rate (for example, spinners), or they received much of their remuneration in kind (servants), or they accrued income in a family business (farmers’ wives and children helping their parents).”Footnote 41

While it is true that piece rates were common for women in textile manufactures and that in-kind payments were common for women in domestic service, women received cash wages more often than Allen suggests. As our recent study has shown, thousands of wet nurses across Europe – most of whom were married – received monthly cash wages, which in most cases were their households’ main or only income.

Allen's vision also underestimates the importance of in-kind wages for men, particularly in the rural occupations. As shown in Table 2, in-kind remuneration could make up twenty-five to fifty-two per cent of the wages of men farm workers and shepherds in eighteenth-century Spain.Footnote 42

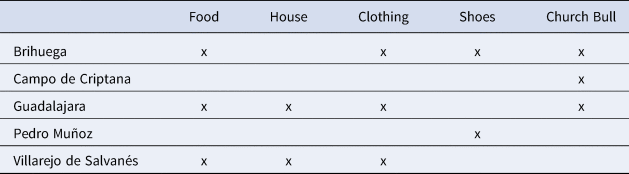

Women's in-kind wages, however, differed in important aspects from those paid to men. These differences reflected women's position in the labour market with regards to participation rates, occupational structure, and wage systems.Footnote 43 Fewer women were recorded as gainfully employed than men in La Mancha. Among the employed, a much higher proportion of women worked by the piece than did men, largely because of the region's widespread textile activity. Textiles required great numbers of spinners, lace makers, and stocking makers – all occupations that were held by women and paid by the piece. Piece payments were exclusively monetary, so here was another large contingent of women workers who fell outside the world of in-kind payments. Two large textile factories are included in my sample, one in Brihuega and one in Guadalajara. Both were royal factories, and each employed hundreds of men and women, all of whom were paid in cash, according to their positions and the number of days worked. But working under contract inside the factories was quite unusual for women. Most women, particularly married women, laboured at home, as textile workers who were paid in cash by the piece.

Domestic service was the second most common occupation for women in my sample of this region. Most domestic servants were paid a combination of cash and in-kind goods and services. The youngest girls, however, received only accommodation, food, and, in some cases, clothing. In Brihuega, for example, fifteen-year-old María Peralonso “earns food and her clothes”. The master of twelve-year-old Manuela Atienza states, “[she is] a poor little orphan whom I only give food so that she helps me”. And Catalina Alonso, aged thirteen, “takes care of the household errands” for one of the factory's cloth weavers, who says, “I only give her food and clothing and shoes for her occupation”.

Table 7 shows the sample's limited data on women's in-kind wages.

Women's wage packages included fewer goods than men's packages. When women did get in-kind payments, the commodities were exclusively consumption goods. Food and lodging were part of the wages of live-in domestic servants, as were second-hand clothing and footwear. Second-hand clothes were usually included in wage packages, but rarely mentioned to Cadastre officials, since they did not generate costs for the employer. New goods that were part of the contract (or their monetary equivalent), were recorded. In Brihuega, Mariana del Cerro, a widow of fifty-four and the errand lady at the convent of Saint Bernardo, was paid 12 ducados, a pair of shoes, and a papal bull. In the town of Pedro Muñoz, three women who worked as servants received 11 to 12 ducados annually plus three pairs of shoes each. (Men working as shepherds and farm labourers received one to four pairs of shoes each year.)

Most notably with food, women workers received fewer and lower-quality consumer goods than men. Women and men ate much of their food at the workplace, where the food they consumed was part of their wage packages. Women’s in-kind food payments were consistently less than men’s, in quantity and in quality. They would receive less bread and wine for a midday meal, for example, or maybe just the bread, with the wine going to the men. Both at home and at work, women got less food.Footnote 44

Gender differences regarding food originated also by the fact that women were excluded from occupations where food (of relatively good quality and quantity) was an important part of the payment. In a late nineteenth century series of descriptions by doctors of living conditions in the Spanish countryside, we read that in Villamarta de los montes (Badajoz): “The Journeymen received food as part of his wage […] but women and children used to eat frugally, consisting only of bread and some vegetables in the season or with fat in the winter […] The living-in agricultural servant eats better quality food […] because at the table he eats the same food than his master does […].” Footnote 45

Church bulls appear as part of the pay of women domestic workers in three localities, while such decrees are mentioned for men (farm workers) in just one locality. María Algora, a fifteen-year-old maid in Guadalajara receives “seven ducados per year and her bull”.

Unlike men, women in my sample were never paid with goods that could be traded. However, other cases have been described that are consistent with tradable payments. In seventeenth-century rural Mallorca, for example, in-kind payments to women working as seasonal olive pickers included several litres of olive oil.

Here, women had few wage-labour options. They were hired to pick olives during the fall and winter and to hoe cereal fields in the spring. “Seasonal olive pickers received a mixed monthly wage, one part money and the other part in kind (oil), in addition to other items, such as lodging, firewood, water, and transport to and from their residence on the property. The in-kind wage consisted of a quantity of oil, between two and six litres per month, that can be assumed to be about 20% of their total income.”Footnote 46

What has never been recorded in the literature is women receiving in-kind payments that could be considered “means of production”, such as land or livestock. Hence, these women's wage packages did not allow them to accumulate assets over time.

In-Kind Wages Paid to Skilled Workers

A last fundamental difference between men and women's in-kind payments concerns payments received by skilled workers. Women, who were excluded from formal learning, were not part of this occupational segment. Skilled workers – who are identified by their occupations and frequently by their ability to sign their declarations – were frequently paid in kind. Their employers were institutions (such as town councils or convents) or wealthy families. We can assume that their negotiating power was high, and yet they, too, received in-kind payments, suggesting that they also viewed such payments as advantageous. Rural doctors and teachers, for example, were paid with cash and grain, and usually with the rights to a house as well.Footnote 47 Table 8 shows in-kind payments for skilled occupations.

Table 8. Payments in kind to skilled men workers.

Barley was more of a “good to work with” or means of production than a consumption good. It was feed for horses, and therefore was only paid to those who used them. All employees who rode a horse as part of their work were paid in part with barley. In the city of Guadalajara, Don Manuel López Espino, the thirty-two-year-old rent administrator for the Marqués de la Ribera, earned 2,000 reales and “30 fanegas of barley for a horse's upkeep” each year. Don José Sanz Lorrio, fifty years of age, was one of three doctors in the city of Guadalajara and a member of the Royal Academy of Medicine of Madrid. As the doctor at three of Guadalajara's convents, he rode a horse for transportation, and was paid in cash, wheat, and barley.

Conclusions

Although non-monetary benefits remain an important component of most workers’ wages in today's industrial economies, development economists and economic historians tend to view such payments as a remnant of older, obsolete labour regimes. But when in-kind wages are assumed to be exploitative, an outcome of market inefficiencies, or simply the result of limited supply of coinage, their actual economic functions can be obscured. Once we drop the constraints imposed by such assumptions and look at the historical evidence, we are forced to confront the possibility that workers actually used them to their advantage.

As in the rest of Europe, monetary wages were widespread in eighteenth-century Spain, even in domestic service. Money wages were workers’ only source of cash, giving them the liquidity to pay taxes and rent on land and houses (though rent payments were frequently made in-kind). Yet, in-kind payments were a central component of wages in many sectors, often comprising fifty to one hundred per cent of total wage packages. Taking them into account would make our wage series more significant and realistic. Yet, the importance of in-kind wages goes beyond their amount. In-kind payments usually consisted of commodities and services that covered basic needs of the workers. As it has been argued for Italy, in-kind payments allowed workers to cover most of their food needs (and perhaps part of their families’, too). This wage system helped them withstand periods of rising prices, and should therefore be included in any historical analysis of markets and living standards.Footnote 48

The advantages of non-monetary wages are well studied from the employer's perspective. Masters and landowners used in-kind wages to get rid of stock that otherwise would be difficult to sell, to deal with scarcities of cash, and as a strategy to increase workers’ productivity and “job attachment”, thereby decreasing turnover. For workers, the advantages of in-kind payments are less well known.

In this article, I looked at primary sources that make it possible to analyse the functions of in-kind wages in two historical cases of Spain. These sources allow us to hear people's voices. In the first case, workers placed advertisements in Diario de Madrid, detailing how they wished to be paid: with housing and food. War had led to a collapse in agrarian production; food was scarce; inflation had made basic necessities unattainable. As a result, money wages were no longer useful. In the second case, workers’ declarations to tax officials of the Ensenada Cadastre reveal the terms of the labour contracts they had negotiated and agreed upon. In-kind wages were an important part of wages for most workers, but especially for skilled workers and for senior shepherds and farm servants. These rural workers sought wage packages that included livestock or land (or other tradable commodities), which allowed them to become owners, albeit on a small scale. Both of these Spanish cases reflect patterns that can be observed across historical Europe, and today's world. Non-monetary payments could be beneficial to workers, who understood this quite well and therefore actively sought them out.

An examination of empirical evidence leads us away from the notion of a linear evolution from “in-kind to monetary”. Many of those asking for jobs as domestic servants in early-nineteenth-century Madrid had previously been money wage earners, as civil servants, teachers, or small entrepreneurs. As war and inflation ravaged the economy, their interest in money wages evaporated. Meanwhile, the shepherds and farm servants of eighteenth-century La Mancha negotiated wage packages that included money and non-monetary components such as sheep, free grazing, access to land, and grain. As both examples show, the different forms of in-kind payments must be examined because those forms – not just overall wage levels – helped determine labour supply, social and occupational mobility, and even capital formation.

Thus, in-kind payments were an important, structural component of wages for two very different groups of workers. Domestic servants – typically, children, women, and poor rural workers – were paid little and had little negotiating power. In general, they had to accept whatever they were offered – basic consumption goods, such as food and lodging, and some second-hand clothing. The Madrid case shows that in situations of economic and social crisis, individuals who were normally not in this weak position – including members of the middle class – would actively seek the in-kind remuneration associated with domestic work. The other group is at the opposite end of the social spectrum – shepherds and farm servants at the top of the rural work hierarchy. These individuals did not demand in-kind payments to avoid destitution, but rather as a means to expand their options for improving their living standards, and even to benefit from the symbolic and social value of the goods received. Being paid in part with barley was surely important to those riding horses not just for monetary reasons, but also socially, as it confirmed their right to use a means of transport that reflected their superior status.

Analysing the goods and services that made up in-kind payments also provides a fuller understanding of gender wage gaps. Such wage gaps were not just quantitative, but qualitative – women were excluded from certain kinds of in-kind remuneration. Since women were not offered land, sheep or other commodities that could be traded, sold, or accumulated, their ability to save and achieve economic independence was limited. Non-monetary wages gave workers options that cash wages did not, and so created and reproduced fundamental inequalities among different groups.