INTRODUCTION

From its inception, the economy of the captaincy, later province, of Minas Gerais was dependent on slave labor. The earliest regiment that regulated land grants in the mining district tied the size of mining concessions to the number of enslaved workers: prospectors received 5.5 square meters of land per slave, for a maximum of sixty-six square meters.Footnote 1 Demand for slave labor led to a rapid growth of the captaincy's enslaved population. The development of ancillary economic activities, equally reliant on slave labor, further contributed to a regional population that, by the mid-eighteenth century, was predominantly made up of the enslaved. As the century progressed, declining gold yields were not enough to undermine Minas Gerais's or Brazil's commitment to slavery. The development of new export crops, the revival of sugar production in Brazil's coastal regions, and the consolidation of food production aimed at domestic markets had, like mining, relied on the labor of slaves.Footnote 2

The wave of abolitionist thinking and efforts that swept the Atlantic world at the turn of the eighteenth to nineteenth century barely impinged upon the prevalence of slavery in Brazil.Footnote 3 While events in Saint-Domingue, the northern United States, and the Spanish Americas challenged the ubiquity of slavery in the Americas, property holders and political leaders in Brazil, as well as in Cuba and the southern United States, remained convinced that their economic well-being and the stability of their societies relied on the preservation of slavery as a labor system and social order.Footnote 4 Ironically, the suppression of Danish, British, and American transatlantic slave trades helped to ensure a larger supply of African slaves to Brazil at a time when new agricultural exploits intensified demand for slave labor, thus strengthening the institution of slavery.Footnote 5 In Minas Gerais, population data from 1786 and 1808 seem to suggest slavery's slow decline: while the overall population of the captaincy increased by almost twenty per cent, its enslaved population decreased by nearly fifteen per cent. However, by 1821, on the eve of independence, the size of the regional slave force was on the rebound.

Population data for Minas Gerais in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century reveal another relevant demographic shift. While the percentage of enslaved residents fell from forty-nine in 1786 to thirty-three in 1821, the population of free(d) African descendants rose from thirty-three per cent in 1786 to forty per cent in 1821. Similarly, the white population grew steadily and was significantly larger in 1821 than it had been thirty-five years earlier.Footnote 6 Late colonial Minas Gerais's population was becoming freer. These numbers suggest that, at a time of growing abolitionist efforts in the North Atlantic, the Spanish Americas, and the Caribbean, the pursuit of legal freedom for Africans and their descendants in late colonial Brazil, and Minas Gerais more specifically, may have had its own unique form. Rather than targeting the trade or slavery itself, efforts in support of the enslaved focused on freeing individuals through the practice of manumission.Footnote 7

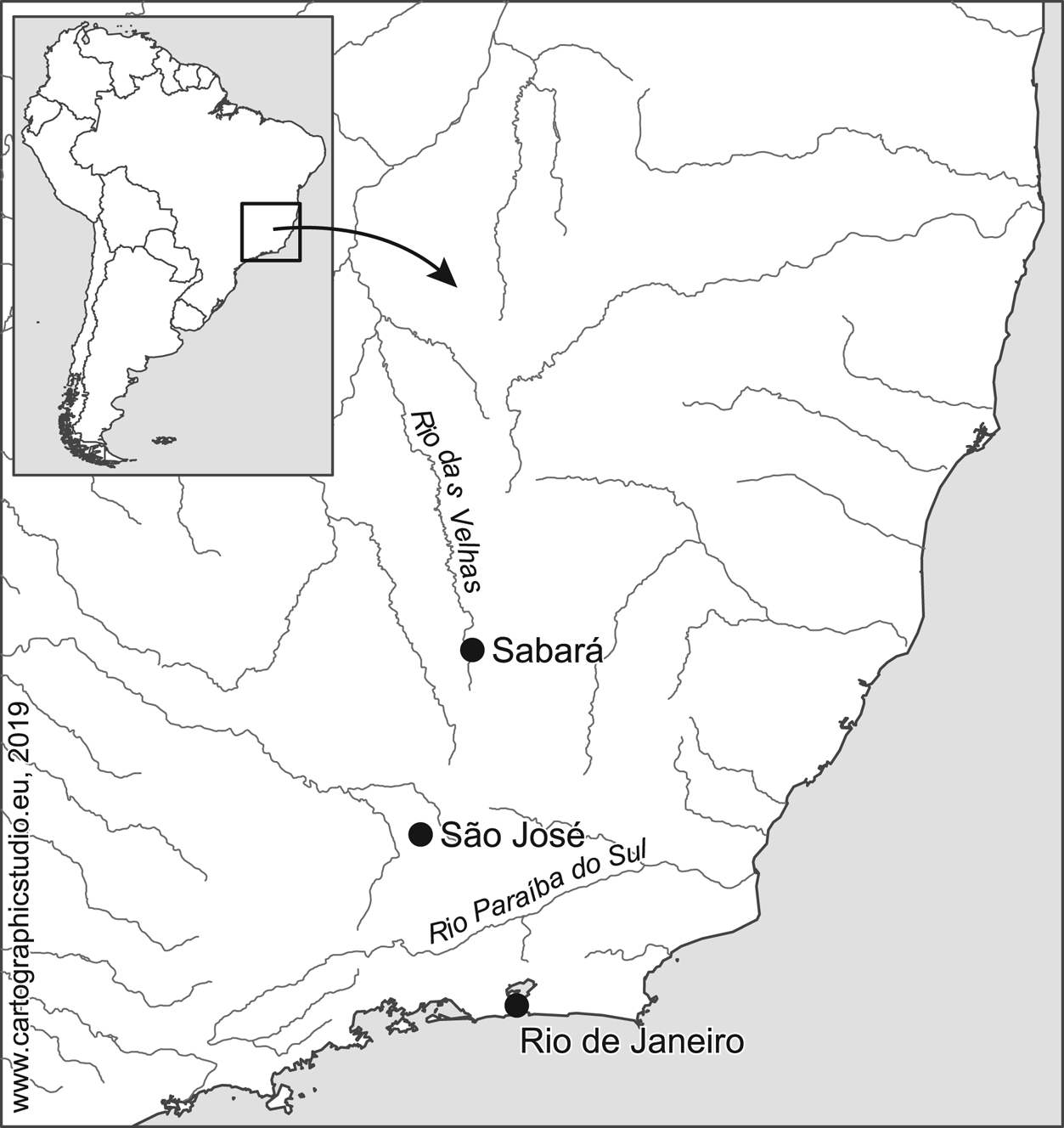

This article investigates the idiosyncratic way legal and final freedom from enslavement for Africans and their descendants was conceived of, articulated, and experienced in one of the strongholds of slavery during an era of Atlantic abolitionist efforts. In late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Minas Gerais, the main systematic challenge to slavery was discrete negotiations of manumission that resulted in the freedom of a few individual slaves. These manumissions, or legal grants of freedom, were often secured through monetary compensation or negotiated labor expectations; occasionally, they were the product of an owner, parent, or relative's gift of freedom.Footnote 8 They fueled the expansion of a free population of African descendants, who congregated most visibly in the captaincy's urban centers, where they became small property holders and, whenever possible, slave owners.Footnote 9 This group's social transition from enslaved to freed property holders, their economic survival, and pursuit of further social upward mobility, relied on their participation in the diverse craft, service, and commercial activities that marked late colonial urban life in Minas Gerais. But it was often their ability to count on local family and social networks to help them integrate into the urban environment and navigate existing hierarchies of socio-racial categories that shaped their access to manumission and experience of freedom. This article examines manumission stories from two African-descendant families in the towns of Sabará and São José (Figure 1) to underscore urban families as key agents of individual freedom in late colonial Minas Gerais.

Figure 1. The location of the towns of Sabará and São José in Brazil.

In his now classic Slavery and Social Death, Orlando Patterson argues that manumission contributed to strengthening rather than weakening the power dynamic created by slavery. Similarly, Brazilian historian Márcio Soares asserts that, established as a gift rather than a right, manumission restructured and reaffirmed ex-slaves’ obligations toward members of the slave-owning class. Freed people, in this sense, formed a category of individuals whose social status was subordinate to that of freeborn slaveholders.Footnote 10 Additionally, because self-purchase or the purchase of family members were widespread, manumissions facilitated the acquisition of new Africans and renewal of the slave force. Ultimately, the possibility of freedom through manumission helped to alleviate conflictive master–slave relations, reinforce the use of slave labor, and strengthen slave society's control over freed people and even freeborn African descendants.

Yet, manumission practices may have also helped to erode the foundations of slavery in Brazil. Individual and family strategies revealed in notarial and parish records from Sabará and São José indicate that some slaves and their relatives viewed the pursuit of freedom through manumission as a de facto if not de jure right. They initiated negotiations, bypassed their masters, and appealed directly to the courts, and expected freedom to be available for purchase if they had the means to buy it. Their actions notably shaped a fast-growing population of free African descendants whose visibility reinforced freedom as a condition within reach. Occasionally the product of family efforts, manumission could also challenge power relationships between white slaveholders and African descendants. Slaves freed by family members were afforded the chance to integrate a social network on terms of relative equality; manumission itself did not reaffirm their subordination to the authority of their former masters. The fragments of family history discussed in this article thus undermine the notion that acts of manumission merely reframed the power relationship between African descendants and white slaveholders. They also illuminate how manumission practices may have fostered public and state intervention in the process of securing the freedom of slaves.

SABARÁ, SÃO JOSÉ, AND THE RISE OF A FREE AFRICAN-DESCENDANT POPULATION IN MINAS GERAIS

The towns of colonial Minas Gerais emerged as a result of the development of gold mining during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. Sabará was incorporated in 1711 and formed by conjoined mining settlements at the confluence of the rivers Sabará and das Velhas. The hamlets’ location on the route to the city of Bahia, then the seat of the colonial government, and its concentration of Portuguese settlers made them the ideal site for a new town.Footnote 11 Sabará's rich mines and its political elevation to the seat of its township (the town proper plus its adjacent rural parishes) and judicial district, the Comarca do Rio das Velhas, quickly attracted a large urban population. By the second half of the eighteenth century it boasted thousands of inhabitants.Footnote 12 The town of São José similarly owed its early settlement to explorers searching for precious metals.Footnote 13 Starting as a crossing station on the banks of the das Mortes river, the hamlet was incorporated as the town of São José in 1718. São José also benefited from its location on a main route, in this case linking the central mining districts to the city of Rio de Janeiro. Unlike Sabará, however, it never became the seat of its judicial district, the Comarca do Rio das Mortes; the town of São João was chosen instead.

If Sabará and São José's beginnings were connected to gold mining, their later economic trajectory was more closely tied to Brazil's growing internal consumer markets. In Sabará and the Comarca do Rio das Velhas, extraction of gold remained a relevant activity throughout the eighteenth and into the early nineteenth century. Yet, already in 1756, a list of the wealthiest men in the captaincy reveals that three out of four elite men in the township pursued other investments. In the Comarca do Rio das Velhas more broadly, merchants were as numerous as miners, while farmers comprised a quarter of the men listed.Footnote 14 São José and the Comarca do Rio das Mortes were never major mining centers.Footnote 15 In 1756, only ten per cent of the captaincy's wealthiest individuals resided in the comarca; among them, less than a third were listed as miners. São José had proportionally more merchants and agriculturists among its residents than anywhere else in Minas Gerais.Footnote 16

By the late eighteenth century, farming had become the predominant economic activity in the two judicial districts. A 1766 count of economic units in Rio das Velhas reveals 1,396 farms and 174 plantations, but only 571 mining sites.Footnote 17 Mining still concentrated a larger enslaved labor force than farming (11,189 slaves versus 9,374, respectively), but by 1804 nearly half of the comarca's enslaved population belonged to farming households.Footnote 18 The Comarca do Rio das Velhas thus contributed to the shift from mining to provisioning local and regional markets that marked the economy of nineteenth-century Minas Gerais.

Most Comarca do Rio das Mortes slaves were engaged in farming activities by the mid-century, if not earlier. The 1766 survey shows more than two thirds of Rio das Mortes's enslaved labor employed on farms and ranches. Additionally, slaveholdings in agriculture averaged 9.5 individuals, as opposed to 6.5 in other comarcas. As farming became economically more prominent in the captaincy, the Comarca do Rio das Mortes's share of Minas Gerais's slave population increased from fifteen to 21.3 per cent between the 1730s and 1760s.Footnote 19 Declining gold output and expanding agricultural activities refocused, moreover, Minas Gerais's provisioning economy as the Rio das Mortes region led the captaincy's efforts to supply the port city of Rio de Janeiro and its lively coastwise trade.Footnote 20

Early nineteenth-century Sabará and São José could therefore be described as farm towns. While the farms of the Comarca do Rio das Velhas, which accounted for twenty-eight per cent of regional households in 1804, were mostly located in rural areas, they nevertheless maintained important economic ties with their urban counterparts (a quarter of all comarca households). Urban merchants, service providers, and small manufacturers provided commercial and material support for farming activities. Conversely, ten per cent of households engaged in urban activities also produced foodstuffs like corn, beans, rice, and manioc.Footnote 21 In the town of São José, 49.1 per cent of all households surveyed in 1806 were headed by craftsmen, small manufacturers, and service providers; another 33.8 per cent were headed by agriculturists.Footnote 22 These economic surveys reveal regional economies that had moved beyond the mining settlements of the early eighteenth century. They further depict urban populations engaged in economic activities that supported local farming and ranching and the provisioning of domestic markets near and far.

The economic history of the towns of Sabará and São José and their respective comarcas was invariably connected to the formation and rapid growth of regional slave populations. Within a few decades after settlement, the Comarca do Rio das Velhas already counted 12,000 enslaved residents.Footnote 23 The connection between slave ownership and gold mining led to the adoption of the capitação, a slave head tax, as a form of collecting the royal fifth (the crown's share) of gold yields. Capitação records show that slaves in Rio das Velhas doubled in number between 1729 and 1750.Footnote 24 By 1767, another 17,290 slaves were added to the regional population, making it the largest enslaved population in the captaincy.Footnote 25 During this period, the township of Sabará concentrated a large proportion of enslaved residents of the Comarca do Rio das Velhas: 7,000 out of 12,000, or fifty-eight per cent, in 1729; and 21,267 out of 49,156, or forty-three per cent, in 1776.Footnote 26 Moreover, the urban parish of Sabará held proportionally more slaves (sixty per cent of all residents) than the judicial district as a whole (forty-nine per cent of all residents) in 1776.Footnote 27

By the early nineteenth century, as gold output declined in Sabará and the Comarca of Rio das Velhas, so did the enslaved population.Footnote 28 Rather than admit to the depletion of gold deposits, local officials argued that a shortage of labor, caused by competition for slave imports from the captaincy of Rio de Janeiro and the Rio de la Plata region, had triggered a general economic slowdown.Footnote 29 It is indeed possible that growing demand for slaves elsewhere affected Sabará slaveholders’ access to enslaved Africans, even though Atlantic slave trading and slave prices were quite stable at the time.Footnote 30 Eventually, Sabará's enslaved population recovered slightly, but it never again accounted for three fifths of town dwellers, as it had in 1776. Between 1796 and 1819, slaves never amounted to more than thirty-five per cent of the urban population.Footnote 31

The declining numbers and diminished relevance of Sabará's enslaved urban population was followed closely by the rise in the numbers of its free African-descendant residents. When, in 1776, census takers counted the township's population of free pretos (persons solely of African descent) and free pardos (persons of mixed European and African descent), it totaled 12,062 individuals and represented one third of the overall population.Footnote 32 By the early nineteenth century, free African descendants had become the largest segment of the population of both the township and the urban parish of Sabará (31,307 and 4,318 respectively), representing in both cases fifty-one per cent of the overall population.Footnote 33 This demographic shift, from a predominantly enslaved to a predominantly free black population, suggests that the town was experiencing more than lack of access to Atlantic slave markets. The urban population had become progressively freer.

In contrast to Sabará, the enslaved population of the township of São José grew steadily during the late eighteenth century, helping to transform the Comarca do Rio das Mortes into the most populated of all four judicial districts in Minas Gerais. The region's dynamic agricultural complex attracted free and freed immigrants and new African slaves in such numbers that its residents, who represented less than a quarter of the captaincy's population in 1776, accounted for 35.8 per cent of Minas Gerais's inhabitants in 1808, and 41.6 per cent in 1821.Footnote 34 The relevance of slaves within this population is clearly evident in the 1795 Rol de Confessados (ecclesiastical nominal list) of the parish of São José. Slaves accounted for 48.2 per cent of the total parish population and 51.9 per cent of residents in the parish's urban seat, a high proportion that is reminiscent of Sabará's earlier demographic profile and attests to a continued local dependence on slave labor.Footnote 35 The significant presence of Africans among the parish slaves (three fifths of all enslaved residents) suggests, moreover, that São José had yet to be affected by any slowdown in the transatlantic slave trade.

São José's enslaved residents, unlike Sabará's, maintained a strong presence through 1808, when they represented 41.8 per cent of the township's total population.Footnote 36 But by 1831, the trajectory of the two enslaved populations were converging again. Having experienced only moderate population growth between 1795 and 1831, the enslaved proportion of the São José parish's residents dropped notably from 48.2 to 39.6 per cent, and in the urban seat of the parish from 51.9 to 38.5 per cent.Footnote 37 Nevertheless, these numbers remained high for a region not directly involved in export agriculture; the parish's economic pursuits continued to support São José's commitment to slave labor.

The 1795 Rol of Confessados also reveals a noticeable presence of manumitted persons who accounted for thirteen per cent of the parish residents. Among this group, 57.7 per cent were described as being of mixed descent (through the terms pardos, cabras, etc.), 26.5 per cent as Brazilian-born African descendants (crioulos), and the rest as Africans. Additionally, 26.8 per cent of parish slaveholders were listed as manumitted, owning mostly from one to five bondspeople. The population of the São José parish also included a group of freeborn pardos and crioulos who comprised 7.6 per cent of local slave owners. Within the urban parish seat, the proportion of manumitted and free blacks among slaveholders rested at just over thirty per cent and over ten per cent, respectively. The specific reference to freed people in the Rol of Confessados reveals São José as a remarkable example of how eighteenth-century manumission practices shaped slave society in Minas Gerais. It also highlights how African-descendant townspeople broadened the social basis of slavery and contributed to its perpetuation.

Between 1795 and 1831, the free(d) population of African descent of the township and parish of São José continued to grow proportionally more significant, exceeding the numbers found for Sabará. In 1808, thirteen per cent of the township's residents were labeled pretos (of pure African descent), and 33.6 per cent were of mixed African and European descent.Footnote 38 By 1831, the majority of the residents in the parish of São José (roughly fifty-seven per cent) were free persons of African descent, while another 2.8 per cent were designated as freedmen. More notably, African descendants accounted for seventy-two per cent of the free population within the parish's urban seat. Unfortunately, the omission or inconsistent use in early nineteenth-century documents of the terms forro or liberto, to designate freed or manumitted, respectively, obscures the relevance of manumission to the shift from slave to free status of São José's African-descendant population. It is possible that such omission merely reflects the tendency to simplify legal stature to a dichotomy between free and slave noticeable in official documentation around the independence of the Brazilian empire in 1822.Footnote 39 It is also possible that the decline in references to freed people (forros) reflects the growing challenges slaves faced to secure their freedom at a time when abolitionist pressures and Brazil's efforts to outlaw and end the illegal Atlantic slave trade raised the price of slaves and, consequently, the price of freedom. The description of a forro population in earlier population lists, tax records, and nominal lists implies, though, that the nineteenth-century prevalence of African descendants among the free population of São José and Sabará was ultimately a product of earlier manumission practices.

FAMILY, MANUMISSION, AND BLACK FREEDOM IN SABARÁ AND SÃO JOSÉ

Enslaved Africans and their descendants in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Minas Gerais repeatedly rejected their condition through acts of resistance, flight, and efforts to form runaway slave communities. Their actions produced a freedom that was often fleeting and inexorably fragile because it was not recognized as legitimate by colonial authorities and property holders.Footnote 40 The formation and growth of the free African-descendant population of Sabará, São José, and Minas Gerais more broadly was closely tied, instead, to the practice of manumission. From the onset, the labor environment created by the mining economy afforded slaves different opportunities to negotiate the purchase of their freedom. Mining sites often hired enslaved workers who were not owned by the holder of the land concession. These slaves, left sometimes to their own devices, were expected to deliver a certain amount in wages to their owners, but could keep part of their earnings.Footnote 41 Similarly, slave women, who were forced to peddle goods and often sexual favors around mining sites to generate income for their owners, were occasionally able to accumulate gold or credit.Footnote 42 In this manner, some slaves secured financial resources to purchase their manumission, usually through payments made over a period of three to five years (a practice referred to as quartação). Such arrangements suited slaveholders, who had little trouble replacing hands thanks to steady supplies of newly arrived Africans. In not a few cases, persons representing slave owners or their family's interests, such as estate executors or legal agents, defended the benefits of offering slaves an opportunity to purchase their freedom. Consequently, in eighteenth-century Minas Gerais the idea that freedom could be within the reach of productive or industrious slaves spread and supported the growth of a free population of African origin and descent even as the enslaved population continued to increase.

The marked gender imbalance of Minas Gerais's early free population, combined with the endemic sexual exploitation of enslaved women, shaped further manumission practices and the formation of a population of free African descendants. The mining district was notorious in the early eighteenth century for its chronic shortage of free white women. In this environment, sexual encounters between free men and enslaved women, though inevitably the product of the coercive and violent dynamic of the slave–master relationship, occasionally led to long-term liaisons, intimate ties, and offspring.Footnote 43 These colonial relationships, forged in the shadow of slavery, rarely resulted in marriages between white men and black women, or in the automatic integration of mixed-descendant individuals into the ranks of free colonial subjects. Nevertheless, they sometimes inspired a sense of moral or familial obligation that led to the manumission of an enslaved child, relative, or sexual partner. This practice became common enough to concern colonial officials that a class of pardos might attempt to claim for themselves the economic and political entitlements enjoyed by their white fathers.Footnote 44 As freed individuals became more numerous in Minas Gerais, and mobilized resources to pursue the manumission of other members of their family and intimate circles, they normalized further the practice of manumission. The large numbers of free African descendants listed in population maps of colonial Minas Gerais reflect more than the economic ingenuity of individual slaves. They also point to a social culture in which manumission had become a family obligation that one generation owed to the next as, together, family members sought to end their enslavement.Footnote 45

* * *

A comparison between manumission records issued in the township of Sabará during the second half of the eighteenth century – referred to as letters of freedom in notarial books – and existing demographic data for that same period suggests that approximately two per cent of the local enslaved population became freed every year. Though a relatively small group, these forros (freed slaves) helped to normalize the practice of manumission. Their access to freedom was similarly achieved through the granting and recording of their letters of freedom by public notaries. Their path to freedom, however, often depended on their place of birth (Africa or Brazil) and racial make-up; their gender and age; and the extent of their economic and social integration. Still, taken together, the experiences of these former slaves helped to define and eventually shape what was possible and expected as other slaves sought a path to freedom.

Two distinct groups stand out among slaves who successfully negotiated their manumission in Sabará. The first were pardo slaves, who represented almost one third of slaves freed between 1750 and 1810 even though they formed only seventeen per cent of the town's slaves in 1776 and seven per cent in 1810. Often descended from a white progenitor, many pardo slaves benefited from their social connections and economic resources to negotiate their freedom. The second noteworthy group were African women. While enslaved women in general attained manumission more frequently than enslaved men, that was particularly true of African women: though only eight per cent of the slaves listed in inventories produced between 1750 and 1810, they corresponded to a quarter of the slaves manumitted during that same period of time in Sabará. The majority of these women, moreover, purchased their freedom, relying on their successful economic endeavors to secure manumission rather than on the circumstances of their birth.Footnote 46

The manumission records of some African women reveal, nevertheless, that their purchased freedom was not merely a financial transaction but a social one as well. Manumission regularly involved the mobilization of the enslaved party's personal or even emotional ties to free or freed persons. The example of Joana, an enslaved Mina, who purchased her freedom from store owner Francisco Gonçalves Machado, is a case in point.Footnote 47 According to her letter of freedom Machado had purchased Joana from a previous owner “for the purpose of her securing the gold with which to buy her freedom”.Footnote 48 The two were compadres, meaning one was godparent to the other's child. That connection seemingly paved the way for the arrangement that allowed Joana to purchase her freedom. In the case of the enslaved Mina Inácia, her owners Belchior Rodrigues Teixeira and Ana Ribeiro Marinho freed her in exchange for the gold she paid and because she had “served [them] well and raised [their] children with much love”.Footnote 49 Inácia's ties to the Teixeira-Marinho family, perceived by them as love, helped her to negotiate the purchase of her freedom. Finally, Romana, also a Mina slave, purchased her freedom from João da Costa Lima, the father of her son. Despite their shared parentage of Manuel, Romana still had to pay for her freedom. But perhaps their connection made Lima more willing to grant her manumission – as well as to allow the father of Romana's other child, Maria, to purchase the girl's freedom.Footnote 50

As freed slaves became property and slave owners in their own right, the dynamics that had supported their pursuit of freedom informed their decisions about their own slaves. In a sample of twenty-six wills of freed black women collected for the period of 1740 to 1808 in Sabará, eighteen referred to slave owners, and eleven contained the details of one or more manumissions. Good service and some claim of affection or intimacy appear in these documents as justification for manumissions that, nevertheless, almost inevitably were quartações, and thus required payment. Common exceptions were the gratuitous manumissions of enslaved children, the daughters or sons of enslaved women owned by the manumitters. Inácia Pacheca, identified as a freed Mina woman, granted her African slave woman Antônia freedom if she paid the executors of Inácia's will 128 oitavas over three years. Yet, Inácia freed Antônia's daughter, Rosa, without requiring any payment, leaving her “free from all slavery as if free from birth”.Footnote 51 These manumissions suggest a few common trends in negotiations of freedom. First, slave owners occasionally exchanged freedom for a slave's sustained service or the means to renew one's labor force by, for instance, purchasing a new slave with the manumission payments of another. Second, it was not rare for owners to willingly offer slaves the chance to buy their way out of captivity. Finally, access to freedom was more commonly extended to an enslaved member of the second generation of one's household, who was linked to the slave owner by perceived ties of affection or a sense of kinship-like obligation.

The trajectory of the Vieira da Costa family further suggests that kinship played a role in emerging manumission practices in eighteenth century in Sabará. The Vieira da Costas had lived in and around the urban parish of Sabará since the beginning of the eighteenth century, where many still resided in the early nineteenth century. The family was headed by Jacinto Vieira da Costa, an unmarried Portuguese man, gold miner, and sugar producer. Jacinto died in 1760, after nominating as heirs to his extensive wealth the eight pardo children he fathered with six different enslaved women. The formation of this family was deeply entangled with the manumission practices of the time. Its first generation comprised parents connected, most likely, by the sexual exploitation that often characterized the male master–female slave relationship. Its second generation was made up of children born in slavery, but who, after being legally recognized by their father as his offspring, were freed and allowed to inherit his wealth. The children's mothers were in most cases also able to pursue their freedom as a result of their intimate connection to Jacinto's household – though none formally joined the family nucleus through marriage. Finally, a makeshift third generation emerges through the letters of manumission: slaves owned by members of the family who were freed in exchange for monetary compensation. From one generation to the next, the Vieira da Costas and their extended household exemplified the possibility of freedom. Their example reified the notion, if not the reality, that freedom was accessible, even if for a price, to those who were linked by ties of affection or familial obligation to free and freed people.Footnote 52

The origins of the Vieira da Costa family resemble that of many other families formed in Minas Gerais during the early eighteenth century. Male Portuguese settlers, empowered by the slave order, pursued sexual contact with slave women they owned or to whom they had access. Those relationships often produced mixed-descendant children born out of wedlock. Occasionally, they resulted in a series of manumissions. The first recorded manumission in the Vieira da Costa family was Jacinto's daughter Ana. Her 1745 baptismal record, which was appended to her father's estate documents, described her as the mulata and natural child of Maria crioula, a slave of Jacinto Vieira da Costa.Footnote 53 It also stated that her godfather had declared her freed. Like many mixed-descendant children, Ana was manumitted at the baptismal font, apparently with no additional conditions imposed on her labor. Jacinto's son Antônio pardo was freed in the same manner in 1751; he was the natural son of Rita, the slave of Maria Fernandes (herself a resident on one of Jacinto's properties). A third child, Ana, the natural daughter of Jacinto's slave Antônia, was also freed at the baptismal font in 1756.Footnote 54 Before his death, Jacinto freed all his other children in his will, drawn up on 9 May 1760, and named them his heirs “for the love I have for them and the assumption that they are mine”. Additionally, he granted them “their freedom manumitting them from now to all eternity as if they had been born free from their mother's womb, that is, those who already do not have their letter of freedom”.Footnote 55 The gratuitous manumission at baptism or in one's will of an enslaved mixed-descendant, the child of a white male father and a black enslaved mother, was relatively common in early eighteenth-century colonial Minas Gerais.Footnote 56 Occasionally, slave owners used the same strategy to free a young or second-generation enslaved member of their household for whom they felt particular affection, responsibility, or even kinship – whether real, suspected, or fictive.

Indeed, Jacinto Vieira da Costa did not limit manumissions to immediate members of his makeshift family. By the time of his death, most of the mothers of Jacinto's children were freed. Jacinto's will does not mention any gift of freedom to these women. Instead, the letter of freedom of Joana Mina, Jacinto's slave and likely the mother of two of his sons, indicates that she paid for her freedom.Footnote 57 Mothering his children may have paved the way to freedom for these women, but they seemingly still had to purchase their manumission. In 1756, when he freed his daughter Ana at baptism, Jacinto also freed Maria crioula in exchange for a “certain amount of gold”.Footnote 58 Maria was the daughter of Inácia Courana or Mina, and possibly the half-sister of Jacinto's oldest son, Antônio Vieira da Costa. It would appear that Jacinto was willing to extend the possibility of freedom to his children's other enslaved kin, but in exchange for compensation.

Antônio Vieira da Costa, like his father, granted a few manumissions during his lifetime. He, however, died a bachelor with no known heirs, including no enslaved descendants. His willingness to free Cecília Mina and Leonarda crioula suggests nevertheless that personal, even intimate ties guided his decisions about manumission. According to Cecília's 1796 letter of freedom, Antônio had inherited her from his mother, Inácia Vieira da Costa; he declared he freed Cecília in recognition of her good services and a payment of 100 oitavas of gold.Footnote 59 Leonarda, on the other hand, was the daughter of Antônio's slave, Maria Pereira Angola; Antônio received 100,000 réis in exchange for her freedom.Footnote 60 Both women purchased their freedom. But the place they held within Antônio's household, one as his mother's contemporary and the other as a dependent born to his estate, may also explain his decision to manumit them. Familiarity, intimacy, and maybe even some sense of obligation toward them could have led Antônio to agree to their freedom.

Isabel Vieira da Costa, a preta forra (freed black woman) and most likely the mother of Jacinto's oldest daughter Antônia Maria and of his son João, was also on the list of Vieira da Costa manumissions. In the late 1770s, a few decades after achieving her freedom, Isabel, then a slaveholder, agreed to manumit her slaves Clemente and Tomé in exchange for payment in gold.Footnote 61 Isabel, like many slave owners before her, used manumission strategically and applied the product of her slaves’ labor to renewing her slave labor force. The economic incentive for these manumissions is undeniable, but was there another reasoning informing Isabel's actions? There were no apparent family ties between her and these men, both of whom were African and designated as Mina. It is possible, however, that Isabel's own experience with freedom, and awareness of the self-purchased freedom of others around her, made her more inclined to offer these men the same opportunity. In other words, in the absence of family or intimate ties, a shared understanding that slaves who had the means to purchase freedom should be given the chance to do so may have moved some slave owners to release their human property.

Slaves themselves seem to have developed an understanding that the pursuit of freedom was a benefit to which they were entitled. In 1780, Nicácio crioulo, the slave of the alferes José Carvalho de Barros, took advantage of his master's death to negotiate his freedom directly with the judge in charge of the settlement of Barros's estate. In his petition to the court, Nicácio argued that he wanted “to give the just amount for his freedom, which was doubly advantageous to the inheritance or the deceased's creditors” since his advanced state of illness would quickly render him valueless. Barros's widow, who was not consulted during the process of manumission that ensued, later protested the transaction. She claimed that Nicácio had acted in bad faith, negotiated his manumission behind her back, and stolen farming equipment to pay for his freedom. But by the time her complaint was recorded and the manumission rescinded Nicácio was long gone, enjoying the freedom he and the judge of the Orphans Court had assumed he had the right to purchase.Footnote 62 Similarly, slaves of the entailed estate of deceased captain Antônio de Abreu Guimarães also assumed that it was their right to purchase their freedom. In an 1805 consultation with the King's Overseas Council, the entailment's governing board declared itself “perplexed by a question raised by some of the preto and pardo slaves of that estate who asked for their freedom offering the price for which they were valued”. The board recognized the economic advantages of selling slaves their freedom to generate funds for the purchase of new slaves. But they were concerned that the terms of the entailment may prevent disposing of the estate's property in this manner. The Council, perhaps to the relief of the board, replied that such manumissions were advantageous and, in fact, recommended.Footnote 63 The Overseas Council, an important branch of the colonial administration, was thus adding its voice to those of local judges, slaves owners, and indeed the enslaved in Sabará, who understood that given the right circumstances slaves should be allowed to bargain for their freedom.

* * *

Sometime during the 1730s or 1740s, two enslaved West Africans, generically designated as Mina, arrived in the town of São José. José (Fernandes da Silva) and Quitéria (Moreira de Carvalho) became slaves to different owners, as the distinct surnames they adopted in freedom suggest. By the late 1740s, they were joined in a union unsanctioned by the Church.Footnote 64 The couple formally married between 1759 and 1764. But a 1775 manumission record, in which José assumed paternity of a son who was born around 1748, attests to the couple's long-standing intimate relationship.Footnote 65 From this initial evidence, it has been possible to piece together a complex family history that spans seven generations and was inextricably tied to a series of manumissions. The example of the Moreira da Silva family, as we have chosen to designate them, lends credence to the argument that family formation and paths to freedom were strongly connected in eighteenth and nineteenth-century Minas Gerais. That connection, moreover, framed manumission as an acquired right rather than a benevolent act on the part of slaveholders and fed the incessant growth of the freed and slave-descended Afro-Brazilian population up to and beyond final emancipation in 1888.

The earliest records of the Moreira da Silva family appear in parish baptismal registers. In 1754 and 1757, Quitéria, an enslaved Mina belonging to Antônio Moreira de Carvalho, baptized two natural daughters, Ana and Antônia, respectively, whose father(s) went unnamed (Figure 2).Footnote 66 In 1759, Quitéria, still unmarried but by then a freedwoman, baptized her son Joaquim. Sometime between March of 1757 and June of 1759, Quitéria (still registered without a surname) had gained her freedom.Footnote 67 It seems relevant that Joaquim's godmother was Rosa Moreira, a preta Mina forra (black West African freedwoman) and the known sexual partner of Quitéria's former owner Antônio Moreira de Carvalho. Born in Lisbon, Moreira de Carvalho appeared on the 1756 list of São José's wealthiest residents.Footnote 68 Like Jacinto Vieira da Costa and numerous other white male slaveholders in colonial Brazil, he pursued a sexual relationship with his enslaved black woman without ever contracting matrimony. He nevertheless acknowledged his illegitimate family: when the couple baptized the youngest of their seven children, a daughter named Rosa, he was listed as the father.Footnote 69 Antônio Moreira de Carvalho must have granted a few manumissions, including that of Rosa.Footnote 70 Repeated acts of manumission, paired with Rosa's appearance as godmother to one of Quitéria's children, suggest that the formation of these two families overlapped to some extent. The context in which Quitéria and three of her children received their respective manumissions was thus indelibly marked by familial and fictive kinship relations.Footnote 71

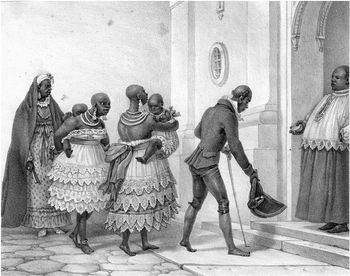

Figure 2. “Negresses Allant a L'Eglise, Pour Etre Baptisées” (black females going to church to be baptized), Jean Baptiste Debret, Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Bresil (Paris, 1834–39), vol. 3, plate 8, p. 129.

The terms of the manumission of two of Quitéria's daughters reveal that she was the main force driving her family's transition from slavery to freedom. In January 1771, Quitéria Moreira, described simply as an African freedwoman, registered the letters of freedom of her daughters Antônia and Ana. The document explains that the actual manumissions had taken place earlier, a few years after Antônio Moreira de Carvalho's death: Antônia was freed in May 1767, when she was ten years old, and Ana in July 1769, when she was fifteen. The two girls’ freedom had been purchased through payments in kind and the estate of Moreira de Carvalho received two recently enslaved Africans in exchange for Antônia and Ana's liberty.Footnote 72 At the time when this document was drawn up, Quitéria and José were already a formally married couple. Yet, only Quitéria appeared as the legal agent seeking to notarize the letters of freedom. José's absence from the record suggests that it was she who had negotiated some sort of agreement relative to the girls’ manumissions, likely before the death of their owner. In the absence of Moreira de Carvalho's inheritance papers, we can only speculate how that negotiation unfolded. It is not inconceivable, however, that Quitéria considered the purchasing of her daughters’ freedom as a matter of course; a right she had earned during her years of servitude, and one that Moreira de Carvalho seems to have recognized. Just the same, the girls’ manumissions were not merely the product of their owner's goodwill. The exchange of two young females for two adult male Africans represented a profitable and highly appealing deal for the Moreira de Carvalho estate. It is also suggestive of Quitéria's commercial acumen. Like many other slave and freed black women in colonial urban Brazil, Quitéria may have worked as a street vendor. But whether or not that was her main economic activity, Quitéria managed to procure the credit and connections with which to negotiate the purchase of two African male slaves.Footnote 73

In July 1775, José Fernandes Silva appeared with his wife Quitéria Moreira (de Carvalho) when the couple notarized the letter of freedom of their oldest son, Severino. The notarial register specifies that they had purchased Severino for the purpose of freeing him from Luiz Francisco de Carvalho, presumably an heir of Antônio Moreira de Carvalho. Then twenty-seven years of age, Severino was a prime slave and his parents almost certainly paid the going market price or more.Footnote 74 It is hard to imagine that Carvalho felt economically inclined to yield a slave at the height of his productive life to immediate relatives. Nevertheless, a refusal to do so may have met with disapproval within the São José community where Quitéria and José were surely well-known and where family ties were respected. Through their hard work and cultivation of social ties, the Moreira da Silva family, parents and children, successfully raised the necessary funds and capitalized on the local social environment to secure the manumission of Severino. Their overall trajectory to freedom, one that likely started with Quitéria's self-purchase, then José's, the couple's formal union, and finally their collective efforts to free family members born into slavery, may well have played out among many slave families.

As the Moreira da Silvas pursued their family's freedom and sought to become property holders and slave owners in their own right, their family trajectory became intertwined with that of other enslaved African-descendant families. In 1772, Josefa Mina, slave of José Fernandes da Silva, inscribed as an African freedman, baptized her daughter Tereza: the godmother was Ana Moreira, José and Quitéria's daughter.Footnote 75 In 1779, Joana Angola, another slave listed as belonging to José Fernandes da Silva, baptized a boy named Joaquim whose godparents were Antônia Moreiras da Silva's husband and, again, Ana Moreira.Footnote 76 Four years later, in 1783, Josefa Mina baptized another daughter, Francisca; José and Quitéria's son Joaquim and his fiancé Genoveva were the godparents.Footnote 77 Finally, in 1790, a slave owned by one of José and Quitéria's sons-in-law baptized an infant boy; again, members of the Moreira da Silva family were the godparents.Footnote 78 Repeating the pattern of entangled slave–master family relationships that Quitéria had experienced while still a slave, the Moreira da Silva formed fictive kinship ties with their own slaves.

The Rol de Confessados of 1795 further illustrates the ways in which now slave-owning members of the Moreira da Silva family developed complex relationships with their slaves and slave families. The then widowed head of household Quitéria Moreira de Carvalho lived with her unmarried son Severino and four adult slaves. Among those were Joana and her fourteen-year-old son Joaquim, whose 1779 baptismal entry is mentioned above. Also residing in the household was Josefa Moreira, designated as Mina quartada, meaning that, although still legally bound to Quitéria, she was in the process of purchasing her freedom. Quitéria, it seems, was giving Josefa the same path to liberty she herself had taken several decades earlier, possibly perceiving it not only as natural but perhaps as a right she had no reason to deny.

Some of Quitéria's children, by then adults, also appear in the 1795 nominal list as heads of independent households and slave owners. Quitéria and José's daughter Antônia Moreira da Silva and her husband Lieutenant Joaquim Martins de Souza formed a household comprising three of the couple's children and two young adult male slaves designated as Benguelas (a common, generic West Central African label of origin).Footnote 79 Absent from the couple's household was Ana, the slave mother whose son was baptized in 1790, and who may have become freed along with her son in the interim. Quitéria and José's son Joaquim Moreira da Silva and his wife Genoveva Maria de Santana formed another household along with Genoveva's brother, a household dependent, and at least two slaves.Footnote 80 The slaves were a twenty-one year old Angola man named Antônio and Francisca, an eleven-year-old crioula and clearly the daughter of Josefa Mina, who was in the process of purchasing her freedom from matriarch Quitéria, as just seen. Josefa's eldest daughter, Tereza, however, resided in another Moreira da Silva household, that of Ana Moreira da Silva and her husband Pedro da Silva Lourenço. This was a simple question of keeping things in the family: recall that Joaquim and Genoveva had stood as godparents for Francisca and Ana Moreira as godmother for Tereza in the respective 1783 and 1772 baptismal acts.Footnote 81

According to the Rol de Confessados, Pedro da Silva Lourenço and Ana Moreira da Silva also owned two African males in their twenties. Additionally, Tereza baptized a son in January of 1795.Footnote 82 Two years later, she bore another son.Footnote 83 It is conceivable that the father of Tereza's children was one of the two enslaved men also owned by Pedro and Ana. It is also possible that she had found a partner elsewhere in the town of São José. Whether the product of disparate sexual encounters or an enduring but unsanctioned union, Tereza's young family helped to increase Pedro and Ana's slaveholding as the turn of the century approached.

A couple of patterns can be gleaned from the 1795 Rol de Confessados and the data examined thus far. Not surprisingly, given the demography of the transatlantic slave trade, all the Africans purchased by members of the Moreira da Silva family appear to have been young adults when the respective transactions took place. Excluding infants encountered at the baptismal font, the four Moreira da Silva slaveholdings described above were composed of six African men, one crioulo, two African women, and three native crioulas. All of the women appeared as mothers in the São José baptismal registers.Footnote 84 These findings are not enough to assert that slave-owning families actively encouraged natural reproduction among their slaves. They nevertheless illustrate how these families benefited from the increase in their enslaved property as a result of the formation of occult, informal families among the enslaved, similar to that of José Fernandes da Silva and Quitéria Moreira de Carvalho up to the 1760s.Footnote 85 Finally, the reference to the Mina slave Josefa's quartação points to a repetition among the Moreira da Silva households of the negotiations of manumission that decades earlier had secured Quitéria and José's liberation from the yoke of slavery.

The third generation of Moreira da Silvas came of age at the turn of the century. The early nineteenth century corresponded to the peak of stable slave prices and the widespread dissemination of slaveholdings.Footnote 86 Not surprisingly, three of these third-generation family members were slave owners. The oldest grandchild, Esméria, was married in November of 1800 and baptized her only daughter in January of 1802.Footnote 87 Two years later, the couple's enslaved woman Juliana appeared in the parish registers baptizing her infant boy.Footnote 88 Esméria herself went on to give birth and baptize three sons between 1805 and 1808.Footnote 89 The timing of these baptisms points to the possibility that, aside from being responsible for most of the housework, Juliana served as a wet nurse to Esméria's boys. Other sources reveal that earlier in her marriage Esméria was a shopkeeper while her husband was a tailor – he also held minor positions in local government right up to his death.Footnote 90 The possibility of relying on Juliana to nurse and look after her children would have freed Esméria to take up spinning or weaving, at the time fast-growing and respectable female occupations.Footnote 91 Ultimately, what stands out is the unmistakable intimacy of the two young families residing together in a single urban household. Neither the slave Juliana nor her son turns up in later sources, so nothing is known of their fate in life. When Esméria and her husband, João Patrício, were inscribed in two nominal lists from the 1830s their household no longer included any slaves.

Manoel Martins Coimbra, like all members of the second and third generations of the Moreira da Silva family, is often described as a crioulo in archival sources. Notwithstanding his African descent, Manoel was ordained a priest sometime in the 1810s. By 1825 Manoel began appearing in the São José parish registers as coajuntor, or adjunct to the parish priest.Footnote 92 Clerics tended to be well-off in eighteenth and nineteenth-century Brazil and Father Manoel was no exception.Footnote 93 He and his spinster sister, Quitéria Maria de Souza, co-owned a townhouse, known as Três Cantos, located on the prestigious Rua Direita. The 1831 nominal list of São José shows Manoel as head of a household that included his sister, a niece, two male and one female enslaved Africans, one crioula and three crioulo slaves.Footnote 94 The following year Manoel passed away. His last will and testament listed one of the African male slaves as his and bequeathed the slave to his sister. It also listed all the native-born crioulo slaves, who were manumitted pending various terms of service to the heirs (Quitéria Maria and their other sister, Esméria).Footnote 95 Three of the crioulos were linked by familial ties: Antônio and Efigênia, recorded as married in the nominal list of 1831, were referred to as man and wife in their owner's will; Vitoriano was revealed to be the natural son of Efigênia in 1854 when, as a freedman, he got married.Footnote 96 Father Manoel's slaveholding thus included a family whose members were all eventually freed, notwithstanding the burdens of years of continued service to his heirs. By the 1830s, the transatlantic slave trade and a golden age of small and widespread slaveholdings were increasingly under threat. Yet, this slave family's example suggests that the connections between family formation and manumission practices constituted a common tradition that Father Manoel felt beholden to honor.

For another two decades, Quitéria Maria de Souza lived in the Três Cantos townhouse along with her niece Bárbara Patrícia Lopes and Bárbara's many children.Footnote 97 Over those years, Quitéria Maria, along with her sister Esméria Martins dos Passos, benefited from the services of the slaves Manoel Martins Coimbra had bequeathed them. Indeed, in the nominal list of 1838 Vitoriano (who later adopted the surname Martins Coimbra) figured simply as a slave belonging to Quitéria Maria in addition to the Africans Maria, twenty-two years old, and Manoel, forty years old. In the urban setting of São José, these slaves were likely hired out or hired themselves out in order to generate income for the household. In 1842, the slave Maria gave birth to a daughter whose father went unnamed.Footnote 98 Typically for Moreira da Silva slaveholdings, Quitéria Maria came to own a slave family. When she died in 1852 the transatlantic slave trade had come to an end. Although she was probably not aware of it, the slave regime she had known for better than seventy years was about to be fundamentally altered by the disappearance of smallholders and, later, by abolitionist threats to the very institution of slavery. In making out her last will and testament, nevertheless, Quitéria Maria followed tradition. The African slave Maria and her daughter were granted manumissions conditioned upon terms of service to Bárbara Patrícia, executor of the estate.Footnote 99 Right to the very end, then, the entangled lives of slave and slaveholding families seemed almost inevitably to lead to manumission.

CONCLUSION

The experiences with manumission shared by the Vieira da Costa and Moreira da Silva families, and slaves in Sabará and São José more broadly, unfolded against Brazil's continued commitment to slavery. During this period, criticisms of the practice of slavery were limited to religious and legal tracts that focused mostly on the nature of masters’ treatment of, responsibilities to, and expectations for their slaves. Authors like Jorge Benci, André João Antonil, and Nuno Marques Pereira encouraged slave owners to show mercy to their slaves and to convert them to Christianity. They sought a moral middle ground, where metropolitan and colonial need for labor could continue to be met by a brutal labor system that destroyed the bodies but, religious thinkers hoped, saved the souls of the enslaved.Footnote 100 The Jesuit priest Manuel Ribeiro Rocha pushed that agenda further. He argued that African slaves, once rescued from paganism, educated in Christian ways, and made to compensate owners for the cost of their redemption, should be given their freedom. Their liberation could happen in four ways: by serving their owners for a period of twenty years; by paying their owners an amount equivalent to twenty years of service; by being freed upon their owner's death; and finally, through their own death, which would accomplish their liberation in the afterlife.Footnote 101 Rocha, however, never called for the indiscriminate emancipation of slaves or end to the enslavement of Africans and their descendants.

Rocha's work was poorly known at the time of its publication. But its discussion of manumission was neatly reflected in the practices of eighteenth and early nineteenth-century slave owners in Minas Gerais. Different manumission records from the captaincy reveal that freedom often resulted from kinship ties between master and slave, from labor negotiations sometimes initiated by slaves themselves, and from the notion that slaves should be allowed to purchase their freedom when able to do so. The development of these manumission practices unfolded, to be sure, at a time when abolitionist views were emerging and influencing policies and struggles around the Atlantic world. Ironically, those broader abolitionist tendencies converged to fortify the Brazilian slave system. The fall of Haiti severely reduced the scope of the French slave trade while the successive suppression of the trade by Denmark (1803), Britain and the United States (1808), and the Netherlands (1814) greatly reduced demand for slaves on the western coast of Africa.Footnote 102 The trade to Brazil, consequently, maintained ample supplies and prices remained stable and low for almost half a century, benefiting agricultural expansion and the multiplication of small slaveholdings.Footnote 103 Notable, as well, was the social dissemination of slave ownership among freed and free African descendants.Footnote 104 Atlantic abolitionism may have thus contributed to black freedom in Minas Gerais mostly by stabilizing slave prices. The availability and affordability of newly trafficked enslaved workers made manumission a low risk transaction for masters, facilitated the purchase of freedom, and fed hopes among the enslaved that negotiating an end to their own or a relative's captivity was possible.

The discussions and eventual laws that constrained and then abolished the trafficking of slaves and enslavement of African descendants in the Atlantic world at the turn of the eighteenth to the nineteenth century would take several decades to develop in Brazil. Indeed, it was not until the 1860s that discernible popular support for full and immediate abolition of slavery emerged.Footnote 105 It may be fair to argue, therefore, that in its long-standing absence of any meaningful opposition, the Brazilian slave system was by far the most consolidated and stable among those surviving into the nineteenth century. An intrinsic part of that slave system was a series of practices which were perceived as contributing to the overall order, morality, and tranquility of the slave society. Among those practices were manumission, acceptance or encouragement of family formation among slaves, and eventually ad hoc support for slaves’ right to purchase, or have purchased, their freedom.Footnote 106 In time, slaves became more adept at mobilizing the support of family and community members in manumission negotiations, and even at redirecting their claims to the right to freedom away from their masters and to courts of justice and the state. The introduction of an outside advocate into negotiations of freedom helped to undermine the absolute power their masters held over them.Footnote 107 As historians of that period, and those practices, we can delight in the slave master class’ complacency and inability or unwillingness to comprehend the subversive nature social relations can acquire over time.