The widespread COVID-19 pandemic led to unprecedentedly rapid vaccination development (Graham, Reference Graham2020). One topic less addressed is vaccine side-effects and their link with anxiety, a condition detrimental to older adults (Bodner et al., Reference Bodner, Bergman, Ben-David and Palgi2021). General anxiety was found in 2.4% of those receiving the Pfizer vaccination (Kadali et al., Reference Kadali, Janagama, Peruru and Malayala2021). Based on the Johnson & Johnson, Janssen vaccination findings, Hause et al. (Reference Hause2021) suggested that common side-effects typical of anxiety, for example, nausea, were driven by anxiety. As psychological factors may impact the immune system (Madison et al., Reference Madison, Shrout, Renna and Kiecolt-Glaser2021), anxiety may even link with side-effects atypical of anxiety (e.g., swollen-lymph-nodes). In addition to general anxiety (Kadali et al., Reference Kadali, Janagama, Peruru and Malayala2021), research showed that vaccination itself may trigger anxiety, for example, its rapid development or an irrational misinformed perception of it being more dangerous than COVID-19 (Bodner et al., Reference Bodner, Bergman, Ben-David and Palgi2021). Thus, we examined in older adults the linking of vaccination anxiety with vaccination side-effects (both typical and atypical of anxiety), whilst controlling for general anxiety.

A representative Israeli sample of vaccinated community older adults participated in this study (N = 939, mean age 68.9 ± 3.43, range 65–85; 59.9% females, 47.2% with academic education; 75.5% married/living with partner). The study was conducted between January 25th and February 4th, 2021; on January 25 cumulative COVID-19 vaccination doses administered per 100 people were 46.73, and on February 4, 62.72. Participants provided informed consent to procedures approved by authors’ university institutional review board and responded 28.15 ± 9.47 days after the first of two Pfizer BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccinations.

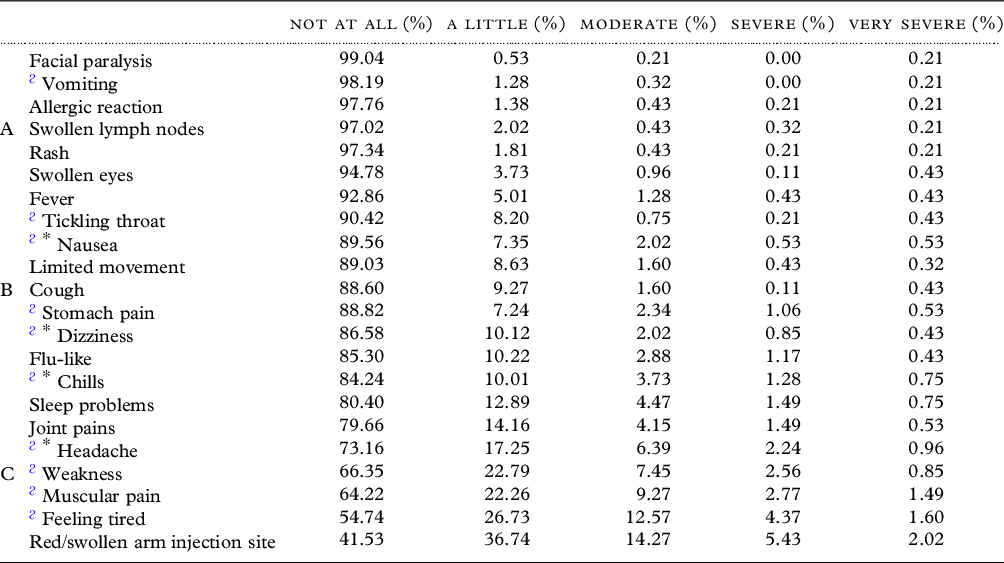

Questionnaire were disseminated via a polling company. Participants rated (1-not suffering at all to 5-suffering very severely) each vaccination side-effect (based on the FDAFootnote 1 and Israeli Ministry of HealthFootnote 2 ), see Table 1. A single item asked to “please rate their vaccination anxiety” (1-not-at-all to 5-very-much). We also assessed general anxiety levels (GAD-7, Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006, α = 0.94). Additionally, participants were asked to subjectively rate their general health (ranging from 1-very bad to 5-very good, Idler and Benyamini, Reference Idler and Benyamini1997).

Side-effects were rare (see Table 1). The average side-effect score was unrelated to number of days from vaccination, higher in females (1.26 vs. 1.18, t = 3.81, p < 0.0001), decreased with age (r = −0.10, p < 0.0001), negatively linked with subjective health (r = −0.19, p < 0.0001), positively associated with GAD (r = 0.23, p < 0.0001), and vaccination anxiety (r = 0.399, p < 0.0001). Neither GAD nor vaccination anxiety linked with “days since vaccination” (p’s > 0.63).

Table 1. Distribution of side-effect severity following the Pfizer BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine (n = 939)

ϩ Liberal depiction of side-effects that may be typical of anxiety; * Conservative depiction of side-effects that may be typical of anxiety

Correlations of anxiety measures with side-effects both typical (see Table 1, depicted by ϩ) and atypical of anxiety were respectively similar (GAD, r = 0.209, p = 0.0001 vs. r = 0.224, p = 0.0001; vaccination anxiety, r = 0.341, p = 0.0001, vs. r = 0.39, p = 0.0001). Limiting typical side-effects to nausea, chills, headaches, and dizziness yielded the same results. Critically, partial correlations show that vaccination anxiety maintained its link with side-effects even after controlling for GAD and subjective health (r = 0.36, p = 0.001).

These results rejoin previous results attesting to vaccination safety and to side-effects decreasing with age (Polack et al., Reference Polack2020). Vaccination anxiety (Bodner et al., Reference Bodner, Bergman, Ben-David and Palgi2021) did not dimmish with time since vaccination, suggesting that such anxiety is less rational. Vaccination side-effects, both typical and atypical of anxiety, similarly linked with anxiety, indicating that rather being driven by overlapping symptoms (Hause et al., Reference Hause2021), anxiety perhaps impacts the immune system (Madison et al., Reference Madison, Shrout, Renna and Kiecolt-Glaser2021). Although vaccination anxiety also stems from irrational misinformation (Berry et al., Reference Berry2021), results suggest that it may be important to one’s physical health.

Alongside this study’s strengths (e.g., a large representative sample, measuring both typical and atypical side-effects and their link with vaccination anxiety, whilst controlling for both subjective health and GAD), limitations are noted. First, we focused on a specific age group and a single vaccination. Moreover, we used a single vaccination-anxiety item which may not as reliable or understood as the longer index (Bodner et al., Reference Bodner, Bergman, Ben-David and Palgi2021). Furthermore, although slightly mitigated by the above partial correlations, future research should control for additional factors that might impact anxiety level, for example, therapy, psychiatric, or medical history. Finally, causality could not be discerned (side-effects driving anxiety or vice-a-versa) in this cross-sectional study.

Yet given the global scale of vaccination programs, the strong link between vaccination anxiety and vaccination side-effects is important both for COVID-19 and perhaps for future pandemics. Data showing infrequent side-effects alongside a relatively robust psychosomatic component may encourage vaccination (Berry et al., Reference Berry2021). Results can aid in identifying persons with anxiety; in turn suitable and effective help to ameliorate this anxiety may be offered, which may possibly alleviate side-effects. Following results, vaccination anxiety (Bodner et al., Reference Bodner, Bergman, Ben-David and Palgi2021) like COVID-19 anxiety (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Cohen-Fridel, Shrira, Bodner and Palgi2020) may benefit from considering strategic health policies that address realistic dangers of vaccination vis-à-vis COVID-19 itself (Berry et al., Reference Berry2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the research authority at Ariel University for their continued support in basic research.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author contributions

Dr Ben-Ezra obtained an internal grant from Ariel University. Drs. Greenblatt-Kimron, Palgi, and Ben-Ezra initiated this project. Drs. Palgi, Greenblatt-Kimron, and Ben-Ezra compiled a questionnaire and organized data collection. Drs. Hoffman and Ben-Ezra conceived the idea for this study and together with Dr Goodwin analyzed the data. Drs. Hoffman and Ben-Ezra, drafted the manuscript. Drs Hoffman, Ben-Ezra, and Goodwin wrote the first manuscript version. All authors wrote, rewrote, and further edited the manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in the study. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy. All authors provided substantially to the drafting and revising of this manuscript.

Sponsor’s role

The study was funded by an internal grant awarded to Dr Menachem Ben-Ezra from Ariel University. The sponsor had no role in the study design or interpretation of the data.