No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

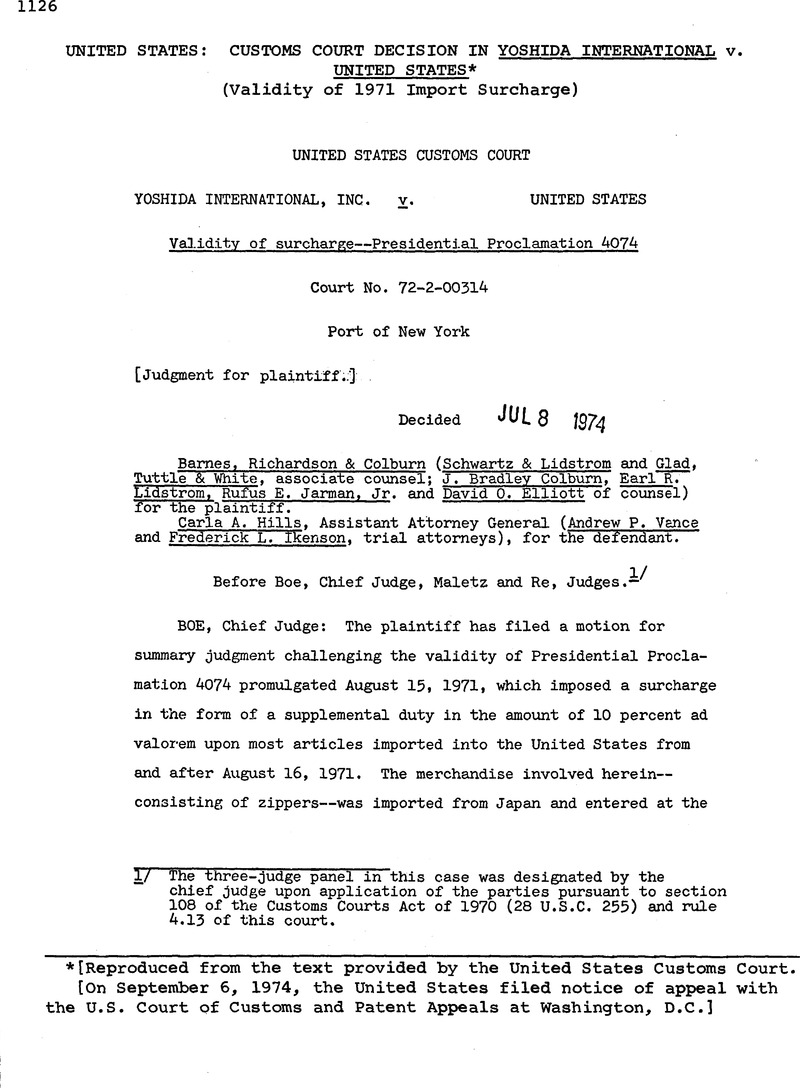

[Reproduced from the text provided by the United States Customs Court.

[On September 6, 1974, the United States filed notice of appeal with the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals at Washington, D.C.]

1/ The three-judge panel in this case was designated by the chief judge upon application of the parties pursuant to section 108 of the Customs Courts Act of 1970 (28 U.S.C. 255) and rule 4.13 of this court.

2/ Section 2(b) of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (19 U.S.C. 1352(b)) provides:

(b) Every foreign trade agreement concluded pursuant to this part shall be subject to termination, upon due notice to the foreign government concerned, at the end of not more than three years from the date on which the agreement comes into force, and, if not then terminated, shall be subject to termination thereafter upon not more than six months’ notice.

Section 255(a) of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (19 U.S.C. 1885(a)) similarly provides:

(a) Every trade agreement entered into under this sub-chapter shall be subject to termination or withdrawal, upon due notice, at the end of a period specified in the agreement. Such period shall be not more than 3 years from the date on which the agreement becomes effective. If the agreement is not terminated or withdrawn fron at the end of the period so specified, it shall be subject to termination or withdrawal thereafter upon not more than 6 months’ notice.

3/ Thus, the General Counsel of the Treasury in his opinion with respect to the legal basis for the imposition of the surcharge predicated the action of the President in making this assessment on the termination authority. Op. General Counsel (Treas. Dept.) No. 822, Sept. 21, 1971.

4/ See also United States v. Metropolitan Petroleum Corp., 42 CCPA 38, C.A.D. 567 (1954); Barclay & Company, Inc. v. United States. 47 CCPA 133, C,A.D. 745 (1960).

5/ See Presidential Proclamation 3762, 81 Stat. 1076 (1967), by the terms of which Presidential Proclamation 3455 was terminated in whole and Presidential Proclamation 3458 was terminated to the extent that it modified Presidential Proclamation 3455.

6/ S55 Cong. Rec., 65th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 484 the actions of the conferees with respect to H.R. 11970, indicated that several factors led to the rejection of section 353 in conference (108 Cong. Rec. 22182 (1962)):

*** Section 353 was a sword which could cut two ways: First, one problem was that there was no procedure prescribed for ascertaining the facts and, second, the other problem was that the Congress did not retain the same opportunity for review as the other sections of the bill provide. [Emphasis added.]

7/ Section 5 of the 1861 Act provided:

[A]11 commercial intercourse by and between the same and the citizens thereof and the citizens of the rest of the United States shall cease and be unlawful so long as such condition of hostility shall continue; and all goods and chattels, wares and merchandise, coming from said State or section into the other parts of the United States, and all proceeding to such State or section, by land or water, shall, together with the vessel or vehicle conveying the same, or conveying persons to or from such State or section, be forfeited to the United States: Provided, however, That the President may, in his discretion, license and permit commercial intercourse with any such part of said State or section, the inhabitants of which are so declared in a state of insurrection, in such articles, and for such time, and by such persons, as he, in his discretion, may think most conducive to the public interest; and such intercourse, so far as by him licensed, shall be conducted and carried on only in pursuance of rules and regulations prescribed by the Secretary of the Treasury.

8/ Hearings on H.R. 4704, House Comm. on Interstate and Foreign Commerce, 65th Cong., 1st Sess., May 29, 31 and June 4, 1917; Hearings on H.R. 4960, Senate Subcomm. of Comm. on Commerce, 65th Cong., 1st Sess., July 23, 24, 25, 27, 30 and August 2, 1917.

9/ H. Rep. No. 85, 65th Cong., 1st Sess., June 21, 1917; S. Rep. No. 111, 65th Cong., 1st Sess., August 23, 1917; H. Rep. No. 155, 65th Cong., 1st Sess., September 21, 1917.

10/ 55 Cong. Rec., 65th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 4840–4879, 4907–4530, 4968–4989, 6949–6958, 7007–7025 (1917).

11/ Letter from Secretary William G. McAdoo to Senator Ransdell, dated September 11, 1917, 55 Cong. Rec., 65th Cong., 1st Sess., p. 7013. See also comments of Senators Reed and Ransdell, 55 Cong, Ree., pp, 7012–7014.

12/ Section 11, above referred to, provided:

Whenever during the present war the President shall find that the public safety so requires and shall make proclamation thereof it shall be unlawful to import into the United States from any country named in such proclamation any article or articles mentioned in such proclamation except at such time or times, and under such regulations or orders, and subject to such limitations and exceptions as the President shall prescribe, until otherwise ordered by the President or by Congress: Provided, however. That no preference shall be given to the ports of one State over those of another.

13/ The license powers accorded to the President terminated at the close of World War I and became effective again automatically at the outbreak of World War II. On the other hand, section 11 and the broad powers included therein, were of a temporary nature and were terminated at the close of World War I. See Markham v. Cabell. 326 U.S. 404 (1945).

14/ 12 Stat. 255, 257 is quoted in part in footnote 7, supra.

1/ See e.g., The Julia, 12 U.S. (8 Cranch) 181, 19? (1314); The Rapid. 12 U.S. (8 Cranch) 154, 161 (1814): Hanger v. Abbott, 73 U.S. (6 Wall.) 532, 535 (1868); Coppell v. Hall, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 542, 554 (1869); United States v. Lane, 75 U.S. (8 Wall) 185, 195 (1869); Insurance Co. v. Davis, 95 U.S. 425, 429 (1877).

2/ S. Rep. No. 111 65th Cong., 1st Sess. (1917), p. 1. See also Ex Parte Kumezo Kawato, 317 U.S. 69, 76 (1942).

3/ On August l6, 1861, the President issued a Proclamation (12 Stat. 1262) declaring that the inhabitants of certain States, with some exceptions, were in a state of insurrection; that all commercial intercourse with them was unlawful; and that all goods coming in from those States “without the special license and permission of the President, through the Secretary of the Treasury” would be forfeited to the United States. On February 28, 1862, the President issued an executive order licensing and permitting such commercial intercourse between the inhabitants of the areas declared to be in insurrection and the citizens of the States of the Union “within the rules and regulations which have been or may be prescribed by the Secretary of the Treasury for the conducting and carrying on of the same on the inland waters and ways of the United States.” See Hamilton v. Dillin, 88 U.S. (21 Wall.) 73, 76 (1875). This was subsequently revised by the “License of Trade” issued by the President on March 31, 1863, permitting commercial intercourse with inhabitants of the insurrectionary States pursuant to regulations adopted on that same date by the Secretary of the Treasury and subsequently modified on September 11, 1863. Id. at 77, 78. The following year, the licensing of commercial intercourse by private citizens with inhabitants of the insurrectionary areas was vastly circumscribed and restricted by sections 4, 8 and 9 of the Act of July 2, 1864 (13 Stat. 376 and 377). See United States v. Lane, 75 U.S. (8 Wall.) 185, 186–187 (1869).

4/ In fact, the contrary position was taken by the Supreme Court in Hamilton v. Dillin, supra. 88 U.S. 73. There the appellant contended that a license fee required by Treasury Department regulations to be paid as a condition for obtaining a permit to purchase cotton in insurrectionary areas was illegally exacted on the ground that it was essentially a tax and, therefore, an improper exercise of Congress power under the Constitution “to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises.” Id. at 81. The Court, however, rejected this argument, holding that the license fee was not a tax imposed under the taxing power, but a “bonus” imposed under the war power of the government; that the power of the government to open and regulate trade with the enemy was intended to be conferred upon the President and the Secretary of the Treasury in the Act of July 13, 1861; and that this included the power to impose such conditions as they saw fit, including payment of a license fee. The Court held (Id. at 94 and 97):

*** The conditions exacted by him [the President] were not imposed in the exercise of the taxing power, but of the war power of the government. The exaction itself was not properly a tax, but a bonus required as a condition precedent for engaging in the trade.

It is hardly necessary, under the view we have taken of the character of the regulations in question, and of the charge or bonus objected to by the plaintiffs, to discuss the question of the constitutionality of the act of July 13th, 1861, regarded as authorizing such regulations. As before stated, the power of the government to impose such conditions upon commercial intercourse with an enemy in time of war as it sees fit, is undoubted. It is a power which every other government in the world claims and exercises, and which belongs to the government of the United States as incident to the power to declare war and to carry it on to a successful termination. We regard the regulations in question as nothing more than the exercise of this power. It does not belong to the same category as the power to levy and collect taxes, duties, and excises. It belongs to the war powers of the government, just as much so as the power to levy military contributions, or to perform any other belligerent act. [Emphasis added.]

5/ Testimony of Mr. Warren at Hearings on H.R. 4704 (the Trading with the Enemy bill) Before tile House Comm. on. Interstate and Foreign Commerce, 65th Cong., 1st, Sess. (1917), p. 32.

6/ Testimony of Mr. Warren at. Hearings on H.R. 4960 (the Trading with the Enemy bill that was subsequently enacted) Before a Subcomm. of the Senate Comm. on Commerce, 65th Cong., 1st Sess. (1917), p. 131. See also testimony of the General Counsel of the Federal Reserve Board, id. at pp. 196-216; 55 Cong. Rec. 4852-4857 and 4862-4863 (1917). The Senate Commerce Committee in reporting out H.R. 4960 noted that the bill was susceptible of division into four portions. Thus, the Committee stated (S. Rep. No. lll, 65th Cong., 1st Sess, (1917), p. 3:

The first portion definas the word “enemy” and prescribes the acts which shall be forbidden and which are made criminal if performed without license.

The second portion provides for a system by which any act otherwise unlawful and criminal may be licensed * * * if compatible with the safety of the United States and the successful prosecution of the war.

The third portion deals with the conservation and utilization of enemy property during the war.

The fourth portion deals with the entirely separable question of patents.

7/ The Congressional hearings, reports and debates thus referred to are cited in footnotes 8, 9, and 10, respectively, of Chief Judge Boe’s opinion.

8/ Letter from Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo to Senator Ransdell, dated Sept. 11, 1917, 55 Cong. Rec. 7013 (1917).

9/ Sections 3(d), 4(b), 13 and 14 of the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, which also referred to the “present war,” similarly terminated at the conclusion of World War I.

10/ There was one exception to the termination of section 11, which exception was effected by the enactment on November 19, 1919 of H.J. Res. 269 (41 Stat. 361). That statute provided that “notwithstanding the prior termination of the present war,” the provisions of the Trading with the Enemy Act and of any Presidential Proclamation issued pursuant thereto which prohibited or controlled the importation of dyes and other products derived from coal tar were to be continued to January 15, 1920.

11/ Prior thereto, on September 24, 1918, the President was authorized under section 5(b) to regulate or prohibit “by means of licenses or otherwise” the hoarding or melting of gold or silver coin, bullion or currency, and to regulare (until two years after “the termination of the present war”) any transactions in bonds and certificates of indebtedness of the United States. 40 Stat. 966.

12/ See H. Rep. No, 2009, 76th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1940), pp. 1–2. In 1941, the House Judiciary Committee pointed out that under the system of property control authorized by the 1940 amendment, “the Government exercises supervision over transactions in foreign property, either by prohibiting such transactions or by permitting them on condition and under license.” [Emphasis added.] H. Rep. No. 1507, 77 th Cong., 1st Sess. (1941), pp. 2–3.

13/ See H. Rep. No. 1507, supra, note 12. See also S. Rep. No. 911, 77th Cong., 1st Sess. (1941), p. 2. With these added powers, the President could “reach enemy interests which masqueraded under * * * innocent fronts.” Clark v. Uebersee Finanz-Krop., 332 U.S. 480, 485 (1947). On the effect of the 1941 amendment with respect to licensing foreign, trade and credit transfers, see Reeves, The Control of Foreign Funds by the United States Treasury, 11 Law & Contemp. Prob. 17, 32 et seq. (1945-46).

14/ The words “instructions” and “importation” were added to section 5(b) by the foregoing 1941 amendment. However, there is no indication in the legislative history of this amendment as to the reason for the inclusion of these specific words.

15/ For an example of regulations which license or authorize transactions subject to executive control under section 5(b) upon declaration of a national emergency, see the Foreign Assets Control Regulations, as amended, 31 CFR Part 500 (1973). These regulations were first published by the Secretary of the Treasury (to whom the President had delegated the powers conferred upon him by section 5(b), 7 F.R. 1409, February 12, 1942) on December 19, 1950 (15 F.R. 9040) under the national emergency proclaimed by President Truman on December 16, 1950, 64 Stat. A454, which has never been revoked.

Section 500.201 of these regulations as amended, provides in pertinent part:

(a) All of the following transactions are prohibited, except as specifically authorized by the Secretary of the Treasury (or any person, agency, or instrumentality designated by him) by means of regulations, railings, instructions, licenses, or otherwise, if either such transactions are by, or on behalf of, or pursuant to the direction of any designated foreign, country, or any national thereof, or such transactions involve property in which any designated foreign country, or any national thereof, has at any time on or since the effective date of this section had any interest of any nature whatsoever, direct or indirect:

(1) All transfers of credit ana all payments between, by, through, or to any banking institution or banking institutions wheresoever located, with respect to any property subject to the jurisdiction of the United States or by any person (including a banking institution) subject to the jurisdiction of the United States;

(2) All transactions in foreign exchange by any person within the United States; and

(3) The exportation or withdrawal from the United States of gold or silver coin or bullion, currency or securities, or the earmarking of any such property by any person within the United States.

(b) All of the following transactions are prohibited, except as specifically authorized by the Secretary of the Treasury (or any person, agency, or instrumentality designated by him) by means of regulations, rulings, instructions, licenses, or otherwise, if such transactions involve property in which any designated foreign country, or any national thereof, has at any time on or since the effective date of this section had any interest of any nature whatsoever, direct or indirect:

(1) All dealings in, including,without limitation, transfers, withdrawals, or exportations of, any property or evidences of indebtedness or evidences of ownership of property by any person subject to the jurisdiction of the United States; and

(2) All transfers outside the United States with regard to any property or property interest subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

(c) Any transaction for the purpose or which has the effect of evading or avoiding any of the prohibitions set forth in paragraphs (a) or (b) of this section is hereby prohibited.

Another example of the exercise under section 5(b) of Presidential authority to regulate international financial transactions is the Foreign Direct Investment Program established pursuant to Executive Order 11387 which was issued on January 1, 1968 (33 F.R. 47) on the basis of the continuing national emergency declared by President Truman in 1950. This program restricts transfers of capital to foreign countries by investors in the United States and requires repatriation to this country by such investors of portions of their foreign earnings and short-term financial assets held abroad.

16 For example, even section 252(a)(3) of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (19 U.S.C. 1882 (a)(3)), which gives the President substantial tariff-making authority is operative only under clearly defined conditions. It authorizes the President to impose duties or other import restrictions “to the exticent he deems necessary and appropriate” on the products of any foreign country or instrumentality, but only in the event that such foreign country or instrumentality establishes or maintains unjustifiable foreign import restrictions against United States agricultural products which impair the value of tariff commitments made to the United States, oppress United States commerce, or prevent the expansion of trade on a mutually advantageous basis. Furthermore, he must first provide an opportunity for the presentation of views concerning such foreign import restrictions which are maintained against United States commerce and, upon request, by any interested person, provide for appropriate public hearings. 19 U.S.C. 1882(d).

17 See Hearings on H.R. 8430 Before the House Comm. on Ways and Means, 73d Cong., 2d Sess. (1934); Hearings on H.R. 8687 Before the Senate Comm. on Finance, 73d Cong., 2d Sess. (1934); Hearings on H.R. 9900 Before the House Comm. on Ways and Means, 87th Cong., 2d Sess. (1962); Hearings on H.R. 11970 Before the Senate Comm. on Finance, 87th Cong., 2d Sess. (1962).

18 See H. Rep. No. 1000, 73d Cong., 2d Sess. (1934); S. Rep. No. 871, 73d Cong., 2d Sess. (1934); H. Rep. No. 1818, 87th Cong., 2d Sess. (1962); S. Rep. No. 2059, 87th Cong., 2d Sess. (1962); Conf. Rep. No. 2518, 87th Cong., 2d Sess. (1962).

19 See, for example, the following Congressional comments on H.R, 11970, which was subsequently enacted as the Trade Expansion Act of 1962: