Article contents

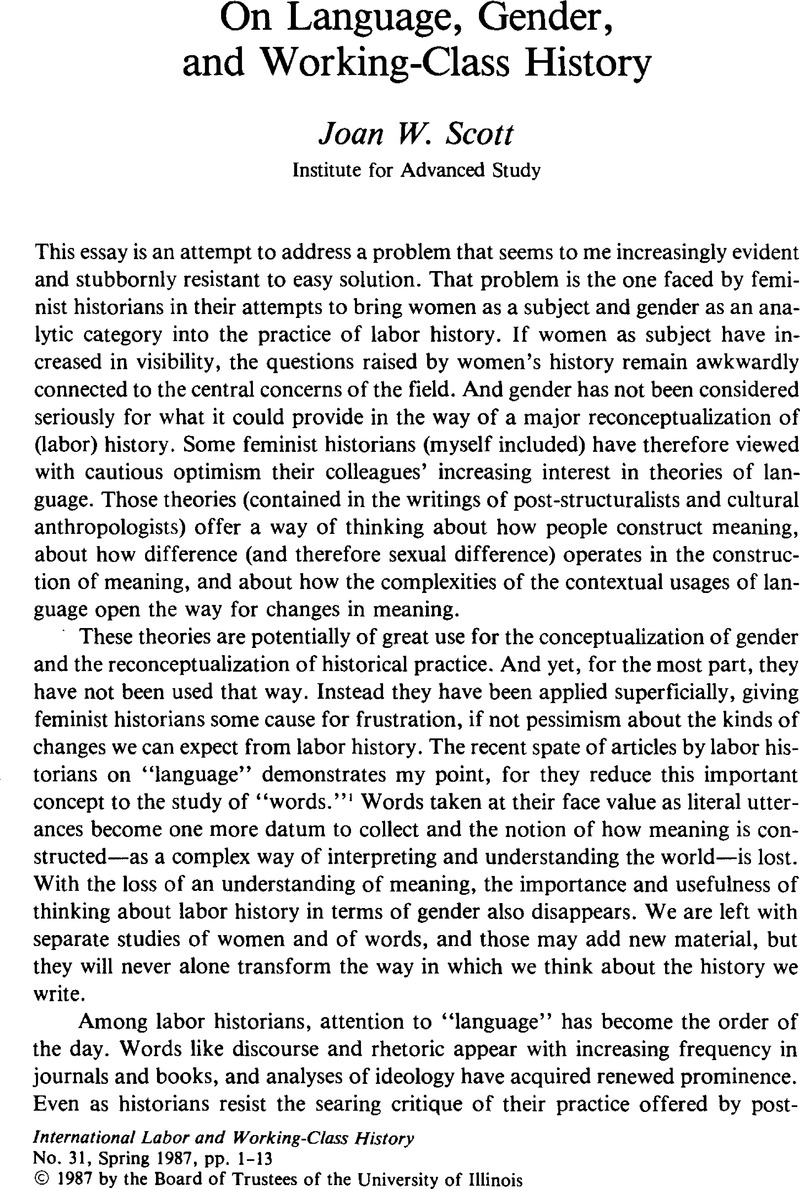

On Language, Gender, and Working-Class History

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 16 December 2008

Abstract

Information

- Type

- Scholarly Controversy

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © International Labor and Working-Class History, Inc. 1987

References

NOTES

I am grateful to Donald Scott and Elliott Shore for their criticism and advice, which helped sharpen and refine my argument.

1. See the editors' introduction to the special issue of the Radical History Review on “Language, Work and Ideology,” No. 34 (1986): 3: “As radicals, we are concerned about the languages of power and inequality: how words express and help to construct dominance and subordination.” The conflation of “language” and “words” is exactly the problem that needs to be avoided and that I will address throughout this essay.

2. Here it is important to point out that being pro-female—that is in favor of women in the profession and even of women's history—is not inconsistent with being anti-feminist—that is opposing a philosophical analysis that tries to explain the subordination of women in terms of inequalities of power as they are constructed in and by systems of social relationships, including class. The outcry against feminism has come from people who claim great sympathy for women; they just don't like to have to reinterpret the history they do in terms which take feminist analyses (of gender) into account.

3. Jones, Gareth Stedman, Languages of Class: Studies in English Working Class History, 1832–1982 (Cambridge, 1983).Google Scholar

4. Sewell, William Jr. has shown a similar logic at work among French laborers in the same period. See his Work and Revolution in France: The Language of Labor from the Old Regime to 1848 (New York, 1980).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

5. The political theorist Carole Pateman points out in an unpublished chapter of her new book on the social contract that what was at stake in liberal theory and in concepts of fraternity was not only male property generally, but also men's (sexual) property in women's bodies.

6. Taylor, Barbara, Eve and the New Jerusalem: Socialism and Feminism in the Nineteenth Century (New York, 1983).Google Scholar

7. Thompson, Dorothy, “Women and Nineteenth Century Radical Politics: A Lost Dimension,” in Mitchell, Juliet and Oakley, Ann, ed., The Rights and Wrongs of Women (London, 1976), 112–38.Google Scholar

8. Alexander, Sally, “Women, Class and Sexual Difference,” History Workshop 17 (Spring 1984): 125–49.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

9. Yeo, Eileen, “Some Practices and Problems of Chartist Democracy,” in Epstein, James and Thompson, Dorothy, ed., The Chartist Experience: Studies in Working-Class Radicalism and Culture, 1830–1860 (London, 1982), 345–80.Google Scholar

- 44

- Cited by