1 Introduction

The problem of women's access to self-defence has been internationally recognised but remains under-examined in a UK context. Fitz-Gibbon and Vannier (Reference Fitz-Gibbon and Vannier2017) have called for an evidence base of women's use of the defence to be developed and recent work has shown how crucial this can be in the context of advocating reform in domestic abuse law and policy (McNamara et al., Reference McNamara2019Footnote 1). Against such a backdrop, this paper presents the findings from original empirical research conducted by the author on women's use of and access to self-defence in the Scottish courts. Specifically, it provides a feminist analysis of (1) national data provided by the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service, (2) reported legal judgments and (3) unreported homicide cases. The empirical data presented support the view that there is a need for reform in this area and the doctrinal analysis offered further demonstrates that self-defence does not adequately reflect women's experience of violence, especially sexual violence, and instead continues to reflect male experiences of (public) violence.

Self-defence is especially significant to an accused given that, if accepted, it results in a full acquittal. The defence has further significance in the context of killings following domestic abuse since a number of commentators have historically posited that when women kill their abusers, they do so in self-defence (Browne, Reference Browne1987; Daly and Wilson, Reference Daly and Wilson1990; Gillespie, Reference Gillespie1989; Johnson, Reference Johnson2008; McColgan, Reference McColgan1993; Ogle and Jacobs, Reference Ogle and Jacobs2002; Walker, Reference Walker1989). Yet, it has been recognised that women do not routinely employ self-defence (in any context) (Fitz-Gibbon and Vannier, Reference Fitz-Gibbon and Vannier2017). This can be located in several overlapping factors such as the male model of self-defence that has developed (Rosen, Reference Rosen1993; Wallace, Reference Wallace2004), pre-trial decision-making and criminal justice systems that incentivise trial avoidance (Sheehy, Reference Sheehy2014). This paper will focus particularly (but not exclusively) on the context of domestic abuse, since this is the context in which most women experience violence and the most common context in which women kill (Caman et al., Reference Caman2016; Chan, Reference Chan2001; Gillespie, Reference Gillespie1989; Moen et al., Reference Moen, Nygren and Kerstin2016) and will attend to four specific research questions: how often women raise self-defence (and in which contexts); how often women are successful with these claims; whether the current law of self-defence in Scotland is able to accommodate women's experiences of violence; and how the law might be reformed in such a way as to accommodate women's claims of self-defence.

This work seeks to inform ongoing discussion about reform of defences in Scotland (Scottish Law Commission, Reference Scottish2021) whilst also providing the evidence base that has been called for by feminist researchers. As such, it represents a significant contribution to socio-legal research on women's access to criminal defences.

2 Empirical data on women's use of self-defence

2.1 Data and methods

Several methodologies were employed as part of this research: analysis of quantitative data provided by the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service (2019), analysis of unreported homicide cases occurring in Scotland between 2008 and 2019, and analysis of case judgments reported in legal journals.

Traditional searches of case judgments were undertaken for self-defence cases that involved female appellants. These searches identified seven appeal cases over the last thirty years related to cases in which women had pled self-defence at trial and been unsuccessful with this claim.Footnote 2

Obviously, appeal judgments account only for those matters that have been appealed following a trial. In all contexts, most criminal cases are not appealed and/or are resolved without a trial (being resolved instead by way of negotiation with the Crown). To counteract this limitation and to identify relevant cases, searches of the judiciary's published sentencing statements and newspaper reports were undertaken.Footnote 3 One hundred and one cases were identified in which a woman was initially accused of homicide (murder or culpable homicide) in Scotland between January 2008 and December 2019. These cases included all types of homicide. In thirty-one of the 111 cases (27.9 per cent), the deceased was the female accused's partner or ex-partner. In one of these thirty-one cases, the deceased partner was female – that is to say, it was a same-sex partner homicide. Reference to prior domestic abuse or previous fighting between the parties was made in twenty of the thirty partner homicides (66.7 per cent).Footnote 4 In one case both the female accused and the male deceased were accused of domestic abuse against one another.Footnote 5

2.2 Centralised data on self-defence

Under Scottish criminal procedure, self-defence is considered a ‘special defence’, meaning that advance notice must be given that it will be led.Footnote 6 The significance of special defences in Scots law has been lessened somewhat by the introduction of ‘defence statements’ whereby the nature of any defence position must be provided to the Crown in advance of trial.Footnote 7 Regardless, it remains a procedural obligation to provide advance notice of self-defence meaning that, in theory, there exists a formal record of how often it is lodged.

Working under this assumption, this author submitted freedom of information (FOI) request to the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Service (SCTS) in March 2019. The request was: how many applications had been lodged to lead special defences over the last ten years by breakdown of the defence and the gender of the accused. The SCTS are clear in advising that the operational case management system that they employ is not for research purposes and is structured around their own operational needs. Their results distinguished between summary (a complaint brought before a sheriff) and solemn matters (more serious matters such as homicides, which involve an indictment and a jury).Footnote 8 Their records showed that in summary matters, 4,905 pleas were made in total between 2009–2010 and 2018–2019. Of these, 2,912 were specifically self-defence pleas (59.4 per cent). Of the self-defence pleas lodged, 716 came from female accused (24.6 per cent) and 2,196 from male accused (75.4 per cent).

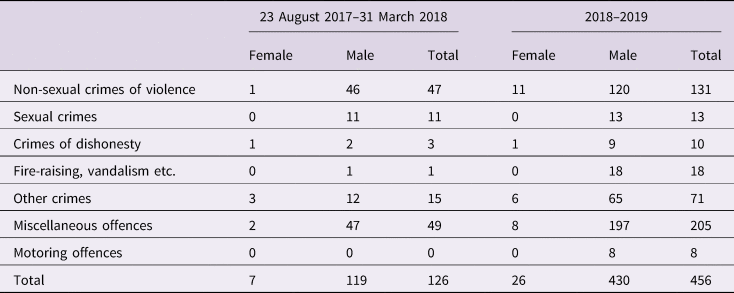

For solemn matters, the same methodology could not be applied and so the search was for a specific special defence type (Table 1).Footnote 9 In April 2019, a follow-up request was made by this author to the SCTS for the data on special defences to be further categorised by charge category. The SCTS reported that between 23 August 2017 and 31 March 2018, a total of 776 special defences were lodged and in the more recent period of 2018/2019, 1,399 were lodged. Those pertaining to self-defence specifically are shown in Table 2.

Table 1. Number of hearings in which a special defence has been recorded in all solemn criminal cases

Table 2. Number of charges in which a self-defence has been recorded in all solemn criminal hearings at Scottish courts, broken down by charge categorya

a It is unclear how self-defence could be lodged in proceedings that involved crimes other than those pertaining to violence, but this was reported for both summary and solemn matters by the SCTS as shown in Table 2. Presumably, this occurs when crimes of dishonesty or crimes against property have been charged but have been done so alongside other crimes of violence and as such have been included in the figures presented by the SCTS.

The figures in Tables 1 and 2 are based on accused person level data, so where two accused in the same case have lodged a special defence, this will return a count of two. The figures shown in Table 2 are also based on the number of hearings and so, where there are multiple hearings in the same case for the same accused person, this will be recorded by the number of hearings rather than the number of accused. Due to the methodology adopted by the SCTS, therefore, these data cannot be relied upon as an indication of how often women use self-defence in practice; the data cannot be fully contextualised since it is unclear how many women were originally accused of the crimes. Interestingly, national statistics on criminal proceedings in Scotland similarly do not provide data on the gender of the accused (other than for conviction rates, which are not distinguished by offence type or type of procedure).Footnote 10 It remains a difficulty, therefore, to accurately identify and assess women's use of self-defence from national datasets alone. The lack of data available on defences is particularly unfortunate given the practice of formal notification that takes place and the larger system of record-keeping that exists in relation to criminal justice data within the jurisdiction.

Although the SCTS data presented cannot be said to add anything to the landscape of what is known about women's access to self-defence, they evidence a broader point: feminist researchers face significant barriers and record-keeping within the criminal justice system can contribute (albeit unintentionally) to the invisibility of women's experiences before the law. Methods of recording data are significant since such recording has the potential to reveal potential injustices (Suresh, Reference Suresh, Motha and von Rijswijk2016). Suresh has described files as an instrument of legal process, noting that they have the power not only to record, but also to create multiple worlds (2016, p. 103). In the context of criminal defences, data can show who is raising a defence, in what context and when such claims are successful. This in turn can facilitate knowledge about particular groups that may be excluded from defences.

Access to ‘sitting papers’ (the case papers that form the Crown case) is a further way in which women's experiences may be rendered invisible. Sitting papers can reveal important information that may be otherwise unavailable to researchers, but access to such papers has been extremely limited in Scotland; they can only be accessed with the permission of the Lord President, who has rarely granted such permission. This issue has been the subject of previous criticism: in 1988 it was recommended in a collection of Scottish socio-legal research papers that the sitting papers of the High Court be made available to all researchers and not only those working for the Scottish government (Scottish Office, 1988, p. 1). Despite such criticism, the position regarding access to these papers remains unchanged almost forty years after this was first identified as a research barrier.

Connelly's work also indicates how useful access to sitting papers can be in terms of examining women's use of criminal defences in practice. She is one of the few independent researchers to access sitting papers; she did so in the context of research that was examining the issue of women who kill their abusers. Her workFootnote 11 attempted to map cases of this type. Using sitting papers, she identified twenty-seven cases between the late 1970s and 2000. Of these cases, twenty-five of the women were charged with murder and two with culpable homicide (both of whom pled guilty). Of the twenty-five charged with murder, eleven faced trial and fourteen pled guilty to a reduced plea. Yet, of the twenty-five, eighteen had originally lodged notices of self-defence (two of whom were acquitted on this ground and one found not proven). This suggests that a number of accused who initially claimed to be acting in self-defence go on to resolve their case by way of a reduced charge without trial, which further indicates that pre-trial decision-making may also play a role in eliminating self-defence as a defence strategy.Footnote 12

2.3 Women accused of homicide and the use of criminal defences

Using legal reports, sentencing statements and media reports, 111 cases were identified by the author involving women accused of homicide (culpable homicide or murder) in Scotland between 2008 and 2019. Ten women faced no further proceedings after their initial arrest.Footnote 13 Three women pled guilty to murder before trial, twenty-six pled guilty to culpable homicide before trial and ten pled guilty to a non-fatal offence before trial. Those who pled guilty to culpable homicide did so on the basis of provocation (30.8 per cent), diminished responsibility (38.5 per cent) and lack of intention for murder (23.1 per cent).Footnote 14 Sixty-two women continued to trial accused of murder or culpable homicide. The defence positions advanced at trial are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Accused's account/defence position where homicide proceedings continued (n = 62)

a This acquittal was accompanied by a restriction order without time limit at a medium-security clinic.

b In this case, proceedings were dropped during trial.

c This defence position would arise where there is a co-accused and all parties are alleged to be responsible through the doctrine of art-and-part liability that allows derivative liability to arise.

d One murder conviction was later quashed on appeal.

As Table 3 shows, ten cases were identified where self-defence was put before the court: none involved an acquittal, four involved convictions for murder, five concluded with culpable homicide convictions and one resulted in a conviction for assault. In the case that resulted in a conviction for assault, the female had killed her ex-partner during a confrontation. The locus was the accused's home and she had used a weapon (a bottle). The case involved significant levels of violence (from someone with previous convictions for violenceFootnote 15). In the cases in which self-defence was led but convictions for murder resulted, the relationship between the accused and deceased were: (1) a female known to the accused through another family member, (2) a female acquaintance and (3) two male partners (here both accused alleged that they were defending themselves against a sexual attack). In the cases in which self-defence was led and a culpable homicide conviction was returned, two involved the killing of a female friend, one involved the killing of a female neighbour, one involved a male flatmate accused of making sexual advances and one involved a male acquaintance who it was alleged tried to rape the female accused.

Amongst the convictions for both murder and culpable homicide, there were killings that took place with weapons and without; those that took place in public and in private; those in which the victim was a female or male acquaintance; and those that involved a co-accused and those that did not. The ages of the females were similar across both groups. Therefore, examining the few homicide cases in which self-defence has been put before the court does not offer a clear pattern as to when the plea is advanced or when it is successful (either fully or partially). However, what can be said is that despite most women in the study group (n = 111) being accused of killing their male partner or ex-partner, and despite the evidence which suggests that most women kill their male partners in self-defence, this was not the common context in which self-defence claims were raised. In only three of the cases (30 per cent) in which self-defence was raised was the deceased a male partner or ex-partner. Most claims (60 per cent) related to the death of a friend or acquaintance. This would suggest particular reluctance to lodge claims of self-defence in the context of intimate partner homicide.

Previous research that has analysed the doctrine of self-defence in the context of rape found no cases in Scotland in which a woman had been acquitted on this basis (McPherson, Reference McPherson2012). This work concluded that misunderstandings may be operating: that whilst the law formally recognises the position that women are entitled to defend themselves against rape, in practice this is limited to rapes by perpetrated by strangers and that problems exist in applying this defence successfully when the context is a sexual attack from a man known to the accused (McPherson, Reference McPherson2012). But, of course, this is the reality of most women's experiences of rape and sexual assault. The Scottish Crime and Justice Survey found that 51 per cent of those who had experienced serious sexual assault since the age of sixteen reported that the perpetrator was their partner and a further 14 per cent reported that the perpetrator was their ex-partner (Scottish Government, 2021, Figure 9.4). As such, the doctrine of self-defence in the context of rape appears to have become divorced from the reality of sexual violence.

2.4 Reported appeal cases

Of the seven reported appeal cases identified, four involved a context of homicide and three of these cases were included in the larger study group discussed (n = 111). Three of the seven reported appeal cases involved unsuccessful self-defence claims in the context of aggravated assault (one against a male acquaintance, one against a female acquaintance and one against police officers). In all three cases, the appeals were successful. In Wilkinson Footnote 16 a retrial was ordered; and in Croly Footnote 17and McCallum Footnote 18 the convictions were quashed. Although this study group represents a small sample of cases, they are suggestive of the fact that the Scottish Court of Criminal Appeal is more willing to engage with women's claims of self-defence in the context of non-fatal offences against the person. In three of the homicide cases in which the appeals were refused, the focus of the appeal was the trial judge's directions on provocation. In Singleton,Footnote 19 the court noted the distinctive nature of self-defence and provocation, commenting that self-defence should not be considered alongside provocation.Footnote 20 However, the practical relationship between the two is obvious and in Early,Footnote 21 the court noted that the evidence required to consider the context of a plea of provocation is the same evidence that must be considered in relation to the question of self-defence. The results from this study show how commonly provocation is pled and accepted in homicide cases involving a female accused, especially where cases are resolved without trial. Elsewhere, it has been evidenced that provocation is the most commonly advanced defence position for women who kill following abuse (McPherson, Reference McPherson2021) and that provocation has been raised in circumstances that are suggestive of self-defence, such as in this example:

‘[The accused and her husband] got into a fight in the kitchen at their home … and he grabbed her by the throat. [The accused] claimed she could not push him off and reached out blindly, grabbing a kettle, but he ducked out of the way and she lost grip of it. Next, she tried to throw a coffee jar at him, with no effect. She said she could feel herself passing out when she picked up a knife and struck out at him. He let go and slumped to the floor. The wound, which was near the top of his left shoulder, cut the pulmonary artery. [The accused] had originally been charged with murder, but pleaded guilty to the lesser offence of culpable homicide.’ (McPherson, Reference McPherson2021, p. 298)

In the appeals of both Croly and Meikle, it was submitted by the appellants that provocation should not have been introduced by the trial judge since it had not been a position advanced at trial. One reading of these appeals alongside the high use of provocation to resolve homicide cases is that potential claims of self-defence are at times subsumed into the plea of provocation as a way to accommodate the facts of a confrontational attack presented by the accused (and the fact that she may have been fighting for her life).

The empirical evidence presented shows that women do not commonly advance positions of self-defence, and that where they do advance this position, the defence is only ever partially successful. A closer examination of the requirements of the defence under Scots law will address whether the law is able, in theory, to accommodate women's claims of self-defence.

3 Self-defence under Scots law

Under Scots law, self-defence can be utilised as a full defence in cases of both fatal and non-fatal violent offences, with the requirements being the same in both contexts.Footnote 22 In order for an accused to avail themselves of the defence, three requirements must be met: the existence of an imminent threat, a response that is proportional and necessary, and that any reasonable opportunity to retreat must be taken. These rules were clarified in the 1954 case of Doherty Footnote 23 and have remained largely unchanged since. In terms of using Scotland as a case-study, the requirement to retreat renders the test for self-defence in Scots law particularly high – a fact that in itself justifies separate consideration of the jurisdiction.

3.1 Imminence

An imminent threat does not require that the accused be in danger of death, only in danger of serious harm. However, fatal force cannot be used against an attack that the accused knows to be non-fatal. Case-law has clarified that imminence of harm will not be extended to include a future threat.Footnote 24 Otherwise, the concept of imminence and its exact meaning have not been the subject of legal attention. This can be related, in part, to the fact that interpretations over what is considered an imminent threat will often be left to a jury who are not obliged to justify their verdict.

The concept of imminence has been the site of particular focus for many feminist commentators on the basis that it is unjust to demand that a woman suffering from domestic abuse wait until an attack is about to take place, even though there could be a period during which they know a deadly attack is reasonable or likely (Ferzan, Reference Ferzan2004, p. 229). The distinction between ‘imminence’ and ‘immediacy’ has also been considered as potentially problematic for women. Specifically, concern has been raised that ‘immediacy’ imposes the need for an instantaneous response, narrowing the timeframe in which a woman must act and implying a more pressing and urgent threat (Ferzan, Reference Ferzan2004; Gillespie, Reference Gillespie1989). Kaufman (Reference Kaufman2007) acknowledges that the terms ‘imminence’ and ‘immediacy’ are often used interchangeably in legal circles but concludes that it is far from obvious that a useful distinction exists in practice. Leverick also notes the distinction, assuming for the purpose of her chapter on imminence that there is no difference, but commenting that there may well be a distinction in practice (2006, p. 87). In keeping with the lack of specification provided on the requirement generally, the distinction between immediacy and imminence has never been the subject of discussion within the Scottish courts as it has been in other jurisdictions.Footnote 25 Suggestions related to the reform of this requirement will be returned to in section 4.

3.2 Proportionality and necessity

The second requirement of self-defence involves two elements: the force used must be necessary as well as proportional to the threat faced. An exception to the position against using fatal violence against a non-fatal attack exists in the context of rape; the position in Scots law has always been that a woman in entitled to defend herself, fatally if needs be, against this type of attack (Hume, Reference Hume1844, p. 224). In practice, however, no woman appears to have been acquitted on this basis (McPherson, Reference McPherson2012). This aspect of the defence suffers from additional uncertainty following the introduction of the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009. The Act extended the actus reus of rape to include non-consensual oral and anal penetration, meaning, significantly, that males could be recognised as victims of rape for the first time. Previously, the doctrine of self-defence in the context of rape had been limited to use by female accused, on the basis that males could not be raped under Scots law.Footnote 26 Since the Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2009 came into force in December 2010, it would appear that no cases have gone before the Scottish courts in which a male accused of an offence against the person has claimed to have been defending himself against a rape.Footnote 27 As such, there exists continuing uncertainty as to the scope of the doctrine that can also be related, in part, to the size of the jurisdiction.

Necessity of force in self-defence pertains to the moral basis of the defence, which holds that the value of human life is higher than anything else and as such must be protected above other rights and interests. It has previously been commented that it is this aspect of self-defence that the law finds particularly troublesome in cases in which women kill their violent partners (McColgan, Reference McColgan1993, p. 527).

In terms of the second aspect of this requirement, Fletcher notes the ambiguity of the term ‘proportionality’, commenting that in other jurisdictions it has been interpreted to mean action that ‘unduly exceeds the interest spared’ or ‘that it is simply greater than the interest spared’ (Reference Fletcher1973, p. 367, footnote 2, emphases added). It would appear that Fletcher's first definition has been adopted within Scots law: proportionality is understood to be actions that unduly exceed the interest spared (Leverick, Reference Leverick2006, p. 359). In relation to the proportionality requirement, the typical differences in size, weight and strength between men and women have been recognised as potentially problematic for female accused, rendering it necessary for them to use a weapon against an unarmed attack.Footnote 28

The approach of the Scottish courts has been to not judge proportionality on ‘too fine scales’Footnote 29 and cases such as HM Advocate v. McNab demonstrate that there does exist scope for a flexible interpretation of proportionality. McNab is one of the few in which a woman has been successful with self-defence at trial level in Scotland. The facts were that Margaret McNab used a knife once, fatally, during an unarmed attack from her violent husband. It was accepted that her use of the knife was proportional, especially given the two-foot size difference that existed between the deceased and the accused.Footnote 30 However, part of McNab's success with self-defence might be located in the fact that she adhered to socially accepted stereotypes of women who kill their abusers, in terms of both her appearance (reference was made to McNab being a ‘tiny wee woman’ during the trial) and her demeanour throughout the trial (apologetic, remorseful, tearful) (Connelly, Reference Connelly1996). In this way, there was no disruption of the gender roles expected of women within criminal trials (Nicolson, Reference Nicolson, Nicolson and Bibbings2000).

This case suggests that self-defence may not be open equally to all female accused who arm themselves with a weapon. This conclusion is further suggested by Moore v. MacDougall Footnote 31 – an appeal against a conviction for assault. Moore and her companion were travelling by bus when they became involved in an altercation with a group of male passengers. Moore's companion was punched by one of the males and Moore was also struck when intervening. Upon being struck, Moore produced a pair of small collapsible scissors and stabbed the male complainer once on each buttock. In refusing Moore's appeal, reference is made to the trial sheriff's comments on her use of a weapon in such circumstances:

‘From the evidence, I am satisfied that the appellant would have been entitled to defend herself with reasonable force such as fists or feet, but I find it impossible to accept that the blows she was receiving from Walls justified the deliberate use of a dangerous, sharp instrument.’Footnote 32

Therefore, it is not a given that the courts will endorse women using a weapon against an attack involving a male.

3.3 The obligation to retreat

Leverick identifies four categories of the retreat rule: no retreat, weak retreat, strong retreat and absolute retreat. Where a ‘no retreat’ rule is adopted in law, the accused who kills in self-defence need not have considered whether an opportunity existed to escape in order to use the defence.Footnote 33 In contrast, where there is an ‘absolute’ obligation to retreat, such an obligation is imposed regardless of the consequences. Although English law abolished the formal requirement to retreat,Footnote 34 the opportunity to escape remains an aspect that will be taken into account when deciding whether or not subsequent actions were reasonable and necessaryFootnote 35 and so could be conceptualised under the ‘weak retreat’ rule that Leverick advances. The fact that any reasonable opportunity to escape must be taken in any context leads her to conclude that Scotland operates a ‘strong retreat’ rule.

For Goosen (referring to her translations of Synman's work), the question of whether there is a duty to retreat is purely academic in this context since it will not be a question of whether a female accused should have fled, but whether they were entitled to go to the lengths they did to defend themself (Reference Goosen2013, p. 94). In this way, the obligation to retreat becomes a discussion about the necessity for action – the aspect of self-defence that McColgan (Reference McColgan1993) believes to be the most problematic for women who kill.

Under Scots law, there is no duty to retreat where the context of self-defence is acting to protect a third party. Instead, the courts have reformulated the requirement as an obligation only to use violence as a last resort.Footnote 36 In a domestic setting, where most domestic abuse takes place (Scottish Government, 2019), this ‘third party’ is likely to be a child or children (Women's Aid). The Scottish courts have never been asked to consider whether an accused/defender is obliged to retreat from their home when children are present in the house. This is yet another aspect of the doctrine particularly significant to women that lacks clarity under Scots law.

This lack of clarity over the application of self-defence within the home contributes to a male model of self-defence that reflects males’ experiences of (public) violence, rather than women's experiences of violence in the home. Rosen (Reference Rosen1993) links the male model of self-defence to the two roots of the defence (‘se defendendo’ and ‘felony prevention’). Similarly, Wallace (Reference Wallace2004) notes that as per natural law, self-defence developed around the two scenarios of ‘stranger in dark alley’ and ‘chance medley’/bar fight. Certainly, fighting has always been defined by society as a masculine activity; male standards of behaviour are automatically imposed on violent confrontations as a result, with no rules existing for the governance of women's responses to male violence (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2002; Gillespie, Reference Gillespie1989). Because aggression and force are incompatible with societal understandings of femininity, a male model of self-defence has been perpetuated with women who kill simply not being perceived as having acted in self-defence (McColgan, Reference McColgan1993).

4 Reform

Internationally, a number of high-profile cases have occurred in which women have been acquitted on the basis of self-defence. The Canadian case of Lavallee Footnote 37 and American case of Wanrow Footnote 38 are perhaps two of the most well known amongst these. Against the background of domestic abuse Angelique Lavallee shot and killed her male partner as he walked away from her. At the Supreme Court of Canada, it was held that expert evidence on battered woman syndrome was needed to dispel stereotypes about victims of domestic abuse and was relevant to the reasonable person standard that had to be met in self-defence.

Yvonne Wanrow shot and killed a known paedophile who entered the premises in which she was staying. Wanrow had been suffering from a broken leg at the time and her leg was in a cast, rendering her disabled. She initially pled guilty but was then represented by feminist attorneys (and self-defence commentators) Elizabeth Schneider and Susan Jordan. It was held on appeal that the jury should have been provided with expert testimony on the matter of her cultural background and that the use of masculine pronouns was inappropriate during the trial, giving the impression that the objective standard to be applied was that for altercations between men. It had led the jury to be misled over the use of a weapon where significant size and strength differences existed. The United States Supreme Court recognised that a subjective view about her perception of harm was appropriate and that the reasonableness of force should also be judged subjectively as this would allow the jury to consider all the relevant circumstances to her act.

The decision-making of legal counsel was similarly key in Lavallee. Here, Greg Brodsky ‘made legal history’ in asking the Supreme Court to consider expert evidence on battered woman syndrome (Sheehy, Reference Sheehy2014, p. 1). There was an acknowledgement that the law of self-defence was based around male experiences but could still be employed in such a manner as to incorporate women's experiences of violence even where the fatality has occurred in circumstances not normally recognised by self-defence. However, Sheehy notes that legal researchers were disappointed by the impact of Lavallee in practice (2014, p. 7). She refers to assessments made in 1994 and 1995 that found only two cases in which prosecutors had declined to prosecute women who had killed their male partners against a background of domestic abuse.Footnote 39 Following Lavallee, a Self-defence Review was commissioned by the federal government in order to review convictions of women who had killed their abusers. This was conducted by Canadian judge, Lynn Ratushny, who recommended a review of seven cases whilst also making recommendations for law reform. Feminist campaigning on the issue of self-defence reform (MacDonnell, Reference MacDonnell2013) ultimately resulted in reform of the Canadian Criminal Code. For MacDonnell, the Canadian law of self-defence now aligns with feminist law reform efforts and ‘stands as good a chance as any of realizing the goals of equality and non-discrimination in the application of self-defence’ (2013, p. 326).

Elsewhere, many commentators have proposed reform of the law in recognition of women's unequal access to self-defence. Willoughby, for example, has previously suggested replacing the imminence requirement with a necessity standard (Reference Willoughby1989, pp. 169–172). Similarly, Rosen's (Reference Rosen1993) proposal for change is that in cases in which women kill violent partners, a judge should instruct a jury that imminence is a required element of self-defence, unless it can be shown that there existed a reasonable belief that the killing in question was necessary, despite the danger not being imminent; if the appropriate burden of proof was met by the defendant, then the jury would be directed on the issue of necessity. Leverick argues against the adoption of a necessity requirement in this way on two bases: first that it would allow juries too much leeway and second that the incorporation of necessity into self-defence would allow less-deserving defendants into the ambit of self-defence (2006, chapter 5). Veinsreideris also argues against the same suggestion on the basis that this could allow prisoners to claim self-defence in response to pre-emptive attacks against inmates (Reference Veinsreideris2000, pp. 630–631).

In Constanza,Footnote 40 the English Court of Appeal considered the meaning of immediacy in the context of stalking and occasioning actual bodily harm. The court rejected the claim that there could be no fear of immediate violence where a perpetrator could not be seen. Although this authority is not binding on the Scottish courts, such an approach could be adopted in the interpretation of imminence, provided that it is accepted that no meaningful difference exists between the concepts of imminence and immediacy. However, this suggestion, and others such as those that propose extending the existing law of self-defence to include situations in which women kill without confrontation (Ripstein, Reference Ripstein1995–1996; Dubin, Reference Dubin1995–1996; Goosen, Reference Goosen2013), run contrary to the findings of empirical studies which show that most women who kill their abusers do so during direct confrontation (Maguigan, Reference Maguigan1991–1992; McPherson, Reference McPherson2021; Nourse, Reference Nourse2001). The fact that women are often successful with the plea of provocation – which requires an immediate loss of self-control – would further suggest that imminence itself is not the main problem in terms of women's access to self-defence. In her empirical study that evidences that most women kill their abusers during confrontation, Maguigan (Reference Maguigan1991–1992) rejects proposals for the reform of self-defence in its current form on the basis that such reform would not change the courtroom climate – fact finders’ prejudices and misunderstandings of women's actions in this context – which prevents women from being successful with the defence. This insight coincides with other commentaries which hold that society is more comfortable with men's claims of self-defence (Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2002) and work that has analysed the gender stereotypes that may take hold in trials on this nature (Nicolson, Reference Nicolson, Nicolson and Bibbings2000; Weare, Reference Weare2013).

Others have proposed that a new defence should be introduced for women who kill their partners. Proposals include a ‘psychological self-defence’ (Ewing, Reference Ewing1987) and a partial ‘self-preservation’ defence (Griffiths, Reference Griffiths, Hanmer and Itzin2000). More recently, and in recognition of the problems concerning the application of self-defence, it has been said that socio-legal re-imagining of self-defence is required (Dayan, Reference Dayan2017; Hopkins et al., Reference Hopkins, Carline and Easteal2018). Such re-imagining might be achieved by the model proposed by Tolmie et al. (Reference Tolmie, Tarrant and Giudice2019). They advocate the implementation of a ‘social entrapment’ model in cases in which women kill their abusers. For them, a social entrapment model would offer an opportunity to move beyond existing paradigms, rooted as they are in historical and cultural inequality. In contrast to the existing ‘bad relationship with incidents of violence’ model currently evident in cases in which women kill their abusers, a social entrapment analysis does not assume that a victim is free from abuse and in possession of autonomy when not under direct attack. Drawing on Stark's model of coercive control, the model does not guarantee the conclusion that a defendant was acting in self-defence, but it does offer an alternative framing of facts. Of course, achieving such re-imagining requires a legal and political framework that is attuned to the context in which women kill and domestic abuse more broadly. Certainly, Scotland has shown itself to be committed to recognising the discreet aspects of coercive control within the criminal law, most recently through the introduction of a distinct offence,Footnote 41 and as a jurisdiction, it has been described as ‘unique’ given the early adoption of a policy approach grounded in a gendered definition of domestic abuse informed by feminist analysis (Brooks-Hay et al., Reference Brooks-Hay, Burman, Mc, Brooks-Hay, Burman and Mc Feely2018, p. 8). However, these developments in law and policy have not up until now considered issues pertaining to women killing their abusers in Scotland.Footnote 42

Any changes implemented would also need to address some of the pre-trial issues related to women's access to criminal defences. In particular, the decision-making of lawyers has been considered a key factor in women's access to self-defence (Bochnak, Reference Bochnak1981; Duivan, Reference Duivan1997; Gillespie, Reference Gillespie1989; Howes et al., Reference Howes, Swaine Williams and Wistrich2021; Rosen, Reference Rosen1993; Schneider, Reference Schneider2000; Schneider and Jordan, Reference Schneider and Jordan1977–1978; Sheehy, Reference Sheehy2014; Thyfault, Reference Thyfault, Osanka and Johann1984, p. 43). Those who have centralised pre-trial stages and lawyers’ understandings of both domestic abuse and women's use of self-defence have focused on the practical reform that could be implemented in order to help women who kill access justice. The pre-trial problems that have been identified include difficulties during consultation stages (all-male legal teamsFootnote 43 and lack of private consultation rooms in prison, exacerbating women's reluctance to discuss personal and sensitive matters) and defence lawyers’ own misunderstandings about domestic abuse. These particular problems suggest that cases that may fit within the rules of self-defence may not reach trial due to other influences in decision-making.

But of course, decisions that are made pre-trial about whether or not to advance a defence are also made with reference to the existing legal requirements of that defence and with reference to the institutional framework of the criminal justice system. In Scotland, as in other jurisdictions, there exists a mandatory life sentence for murderFootnote 44 – a fact that increases the risk of a trial. Further exacerbating this situation is the fact that an accused will benefit from a reduced sentence if they plead guilty at an early opportunity.Footnote 45 In culmination, the result is that many accused (in all contexts) resolve their case by way of a guilty plea being tendered to a reduced charge of culpable homicide. The problems pertaining to plea bargaining have been long recognised for all accused but have been recognised as specifically relevant for women who kill their abusers (Howes et al., Reference Howes, Swaine Williams and Wistrich2021; Sheehy, Reference Sheehy2014). It is likely that if a new defence is introduced without attending to some or all of these issues, then its success would be limited.

As part of their review of homicide and criminal defences to homicide, the Scottish Law Commission have asked whether a specific defence is required for women who kill following domestic abuse (Scottish Law Commission, Reference Scottish2021). One of the questions currently being considered is whether such a defence would operate as a partial or full defence. If such a defence were to operate on a partial basis only, then its introduction would risk exacerbating the existing problems related to women's access to self-defence in the context of intimate partner homicide, encouraging the use of a specialised defence that does not result in an acquittal and would be likely to excuse the accused's actions rather than render them justifiable.

Much has been written about the distinction between justification and excuses in criminal defences (Baron, Reference Baron2005). Justifications have been posited as ‘better’ (Gardner, Reference Gardner, Simester and Smith1996), tending to concentrate on the accused's actions rather than their mental state (Williams, Reference Williams1982). This is especially important for women given the long-standing tendency for their actions to be explained by way of lack-of-capacity defences supported by syndrome evidence (Raitt and Zeedyk, Reference Raitt and Zeedyk2000). Most theorists would consider actions carried out in self-defence to be justifiable and would hold that the accused is neither criminally responsible nor morally responsible for their actions (Ferzan, Reference Ferzan2005). It is crucial that women have equal access to defences that render their actions justifiable in law and society, and so this must also be carefully considered amongst proposals for reform. The introduction of a specialised defence for women who kill their abusers – even one that renders women's actions justifiable – does not attend to the injustices faced by women who kill in other contexts. As such, problems around women's access to self-defence would remain.

5 Conclusion

The empirical data that have been presented indicate that although some self-defence arguments are being presented to Scottish courts on behalf of female accused, women nevertheless have very limited success with the defence. In a homicide context, it has been shown that, over the last ten years, no woman has been acquitted on the basis of self-defence. These results, therefore, support the anxieties that exist over women's access to self-defence and provide empirical evidence in support of law reform.

The analysis that has been undertaken shows that Scotland's law of self-defence, like many jurisdictions, is based around male experiences of public violence with none of the leading authorities on the defence being derived from cases that involved a female accused. The adherence to a ‘strong’ retreat rule marks it out as a jurisdiction in which access to self-defence may be particularly difficult for all accused, but this work has highlighted that the unanswered legal question that exists in relation to the obligation to retreat (whether someone obliged to retreat from their home during an attack if the result is that children will be left with an aggressor) has particular significance for women given their experiences of violence within the home and the likelihood of children being present during abusive episodes. Whilst all small jurisdictions risk having underdeveloped areas of law due to the small number of cases that go before the courts, the lack of clarity over specific aspects of the defence potentially poses unique problems for women, especially in the context of domestic abuse.

There may exist scope for the existing requirements of the self-defence doctrine to be interpreted flexibly and in recognition of the reality of women's experiences, but this will be dependent on (1) a legal team that is able to recognise a woman's claim to self-defence, (2) the institutional frameworks in which pre-trial decision-making takes place and (3) fact finders’ knowledge of domestic abuse and treatment of female accused at trial. A change to the law of self-defence would not remedy all the issues that may negatively impact upon a women's access to the defence, but it may go some way towards providing formal recognition that there exists injustice in this area of law.

It is not the position of this paper that every woman who kills should be able to avail herself of self-defence, but it is imperative that women have equal access to defences that render their actions justifiable. It is hoped that the evidence base that has been presented in this paper will be added to by future researchers. The impact of reform in this area should not be underestimated given the significance it may have for women's participation in the justice system.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professors Fiona Leverick and Elizabeth Sheehy for their helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this work. My thanks also to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive and thoughtful comments.