1 Introduction

Since the early 1980s, the US started requiring social-assistance recipients to participate in sanction-backed mandatory work programmes (MWPs). Subsequently, these types of reforms have progressively flourished in Europe (Lödemel and Trickey, Reference Lødemel and Trickey2001; Handler, Reference Handler2003; Freedland et al., Reference Freedland and Freedland2007; Paz Fuchs and Eleveld, Reference Paz-Fuchs and Eleveld2016). Recipients of social assistance who are required to participate in unremunerated work programmes (hereafter, working welfare recipients) are relatively comparable to employees. They work, like employees, under the supervision and control of another person who is called, in the case of working welfare recipients, a ‘work supervisor’. Besides, they often perform productive work that could equally be achieved by employees. However, their legal status is not yet clear. For example, working welfare recipients are considered to be outside the scope of many provisions of labour law and social security, at the national level (Mahmoudov, Reference Mahmoudov1998; Eleveld et al., Reference Eleveld, Harris, Højer Schjøler, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020; Paz-Fuchs and Eleveld, Reference Paz-Fuchs and Eleveld2016; Studer and Pärli, Reference Studer, Pärli, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020), the EU level (Kountouris, Reference Kountouris2018)Footnote 1 and the international level (Creighton and McCrystal, Reference Creighton and McCrystal2016; De Stefano, Reference De Stefano2021).Footnote 2 In addition, states have generally failed in drafting specific legislation providing them with a comprehensive legal status. This is a remarkable fact, since the protection of the vulnerable party in subordinate employment relationships is considered an important foundation of labour law (Davidov and Langille, Reference Davidov and Langille2011; Davidov, Reference Davidov2016; Collins et al., Reference Collins, Lester and Mantouvalou2018; Zekic, Reference Zekic2019). Arguably, working welfare recipients are particularly in need of legal protection: even more than other subordinate workers, they suffer a vulnerable position because they risk losing their social-assistance benefit, the last social safety net, or part of it if they do not comply with their work supervisor's orders (Eleveld, Reference Eleveld, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020).

In this context, we believe that international human rights provide an interesting framework for gradually leading states to reflect on the elaboration of a protective status for working welfare recipients (Mantouvalou, Reference Mantouvalou2020). Instead of (only) investigating how international human rights provide legal safeguards for working welfare recipients, this paper promotes an experimentalist approach to defining the content of human rights. According to this new adjudication model, international bodies would not define the content of rights once and for all. Instead, from a more dialogical perspective, they would draw on the practical experience of the states in order to gradually determine and refine the content of the rights in a constantly changing environment. This paper aims at exploring how this innovative approach can enable international bodies to acquire a better understanding of the recent phenomenon of MWPs, its diversity and challenges, and how this approach may gradually complement and specify the content of rights in order to ensure effective protection for working welfare recipients.

To this end, we confront the international human rights framework with the MWP legislation and practices of a state: the Netherlands. This human rights framework has been developed by one of the authors through a comprehensive review of the international case-law on international covenants dedicated to social rights (the European Social Charter at Council of Europe level and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and relevant Conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO) at UN level) (Dermine, Reference Dermine, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020a). As for the Dutch case, it has been the subject of extensive empirical observation by the other researcher (e.g. Eleveld, Reference Eleveld2021). Through this exercise, we are engaging in a ‘law in context’ approach in two ways. First, as a theoretical framework, we mobilise the experimentalist approach to human rights that seeks to adapt the content of human rights to local circumstances in order to enhance the effectiveness of the rights in practice. Second, we draw on the empirical findings of a national case-study to identify the gaps in the human rights framework, with the view to refining it or adapting it further.

The paper is organised in the following way. We first explain the experimentalist approach to determining the content of human rights and its advantages over the traditional adjudication model (section 2). After that, we present the human rights framework consisting of six criteria currently used by international bodies to assess the compliance of national MWPs with international human rights law (section 3). We then apply this human rights framework to Dutch MWPs (section 4). The case of the Netherlands is interesting because this country was one of the forerunners in introducing MWPs in Europe (Lödemel and Trickey, Reference Lødemel and Trickey2001) and has continued to implement these programmes on a relatively large scale (Arts, Reference Arts, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020; Eleveld, Reference Eleveld2021; Kampen, Reference Kampen, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020). The case of the Netherlands is also interesting due to the relatively recent extension of the scope of the legal obligation to reintegrate into paid work: it now includes all single parents on social assistance, irrespective of the age of the youngest child. As a result, caregivers can also be assigned to an MWP. By contrast, similar forerunners, such as the UK and Denmark, continue to exclude particular categories of caregivers from the obligation to reintegrate the labour market (Eleveld et al., Reference Eleveld, Harris, Højer Schjøler, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020). This confrontation of law and practice consequently enables us to bring out new concrete issues encountered by states to further develop the international human rights-based framework for assessing national MWPs. Through the empirical observation of the Dutch case, we show, on the one hand, that securing procedural rights is an essential element for working welfare recipients to be able to effectively make their voices heard, to have their social rights respected and to obtain the progressive construction of a real legal status. On the other hand, we highlight that the implementation of MWPs can generate new socio-economic inequalities between women and men if it does not take into account that working welfare recipients are sometimes caregivers (section 5). Based on the findings, we argue that international bodies should include the following procedural safeguards within the human rights framework: the requirement for a written contract between the parties, the securing of the right to information, the introduction of protection against reprisals in case of complaint or judicial action, and the development of mechanisms of collective representation for social-assistance recipients. Furthermore, they should recognise a need to adjust the human rights framework to make it more gender-sensitive.

2 The experimentalist approach to determining the content of human rights

After presenting the difficulties encountered by traditional approaches to social rights adjudication, we show how the experimentalist approach responds to such difficulties (section 2.1). We then explain why we have chosen this approach in this paper (section 2.2).

2.1 The experimentalist approach and the search for effectiveness of human rights

In order to complete their mission of monitoring the application of human rights by states, international bodies must determine the concrete requirements that flow from abstract and indeterminate rights in a specific situation. In carrying out this task, they face an insoluble dilemma between democratic legitimacy and the application of human rights (and the specification of the human rights’ content it implies). Either they determine the concrete requirements of human rights in a straightforward manner and uninhibitedly, thereby risking a loss of democratic legitimacy (judicial activism).Footnote 3 Or they opt for an attitude of self-restraint in the name of the principle of national sovereignty, but fail in their mission of monitoring the application of rights (judicial restraint). The legitimacy concern results from the artificial sequencing of the phases of law-making and application, which implies that international bodies must apply to concrete cases a law elaborated once and for all by states (Dorf and Sabel, Reference Dorf and Sabel1998; Dorf, Reference Dorf2003; Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2010).

Several scholars specialising in theories of democratic deliberation and judicial review have proposed moving away from this artificial sequencing between law-making and its application. From this perspective, they have imagined more dialogical and accountable roles for these bodies that could reconnect human rights and politics, and initiate a positive spiral between legitimacy and effectiveness (Dixon, Reference Dixon2007; Tushnet, Reference Tushnet2008; Young, Reference Young2010). Experimentalist approaches to the adjudication of human rights is one of these proposals. Democratic experimentalism is a general model of institutionalised democratic deliberation elaborated by Michaël Dorf and Charles Sabel (Reference Dorf and Sabel1998). It is based on a central conviction of the pragmatist trend: the reciprocal determination of means and ends. Pragmatists consider that, in a continuous flow, objectives are transformed in light of the experience of their pursuit, to allow, in return, a redefinition of the means. Applied to the adjudication of rights, it commits international bodies to draw on the practical experience of states in order to gradually determine and redetermine the content of rights in a continuous process (see De Schutter, Reference De, De Schutter and Lenoble2010; De Schutter and Moreno Lax, Reference De Schutter and Moreno Lax2010; Gerstenberg, Reference Gerstenberg2014; Dermine, Reference Dermine and Binder2020b).

According to this conception, democratic legitimacy does not derive from the fact that the international body's ‘application’ of the human rights law would be consistent with the spirit of the law ‘made’ by the states. Indeed, democratic experimentalism abandons this distinction, and the sequencing it imposes between a law that would be laid down in perpetuity at the time of its adoption and its application by (quasi-)judicial bodies, which would then be a matter of pure legal technique. Rather, democratic legitimacy stems from the procedure that made it possible to determine the content of the right (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2010). According to this procedural model, international bodies set minimum rules under human rights and national states receive the possibility, and are even encouraged, to deviate from them if they can justify that they are experiencing other benchmarks that aim to better realise human rights. Based on evaluations of the results of the experiments carried out by states, international bodies may then adapt or complement the minimum standards. The new minimum standards are again temporary and bound to evolve – that is, the states may continue to experiment in order to seek to a better realisation of the right (Dorf and Sabel, Reference Dorf and Sabel1998). In this way, democratic experimentalism offers the possibility of progressively determining a right without undermining democratic values, regardless of the degree of indeterminacy of its initial formulation. The dilemma between democratic legitimacy and the application of the law is fading away. A positive spiral between legitimacy and the effectiveness of human rights is created.

2.2 The experimentalist approach and the legal status of working welfare recipients

We have chosen this approach for this paper because it is, first, particularly relevant in the face of the emergence of a new problem or risk that is not yet well defined nor has any potential solutions (Dorf and Sabel, Reference Dorf and Sabel1998): this is the case of the emergence of MWPs and the question of the protection of working welfare recipients. By relying on the knowledge and experience of states, international bodies should be able, with full legitimacy and knowledge, to gradually raise the standard of norms that flow from social rights in order to frame the development of national MWPs.

Second, the experimentalist approach is interesting because it places great emphasis on contextualisation. It allows flexibility of solutions according to local circumstances, so as to ensure greater effectiveness of human rights and to gradually close the gap between law in the books and law in action (Dorf and Sabel, Reference Dorf and Sabel1998).

Third, this approach appears particularly relevant because we have opted, in this paper, to base the evaluation of national MWPs on the international covenants dedicated to social rights. And the monitoring of the application of these covenants is carried out not only through a specific control procedure (the European Social Charter's collective complaints procedure and the individual communications mechanism related to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights), but also through a regular monitoring procedure (state reports). Hence, the reporting procedure allows international bodies to have regular exchanges with state parties on the best way in which to realise social rights and to keep informed of evolving national practices. It makes it possible to follow, compare and monitor the reforms and experiments undertaken by states (Dermine, Reference Dermine and Binder2020b). Based on the experience of the states and the acquired knowledge, bodies can review minimum standards in a continuous process in order to keep pace with changing realities and improve the effectiveness of the protection of the social rights of working welfare recipients. The regular monitoring mechanism could also feed into the development of case-law in specific procedures.

3 The emerging international human rights framework for assessing national MWPs

MWPs imply a sanction-backed legal duty to perform work, which can be questioned from the angle of human rights in at least three ways:

• under the prohibition of forced labour (Art. 4(2) and (3) of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), Art. 8(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 30);

• under the right to freely chosen work, which is a component of the right to work (Art. 1 of the European Social Charter (ESC) and Art. 6 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR));

• under the right to social assistance (protected under Art. 13 of the ESC and Art. 9 of the ICESCR).

While there is not much ‘hard’ international case-law on the topic, we show how the contours of a human rights framework begin to appear through the Conclusions, Recommendations, Questions and ‘soft’ case-law of international supervisory bodies of international social rights. These bodies include the Committee of Experts on the Application of ILO Conventions and Recommendations (CEACR), the European Committee on Social Rights (ECSR) – the monitoring body of the ESC – and the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) – the monitoring body of the ICESCR.

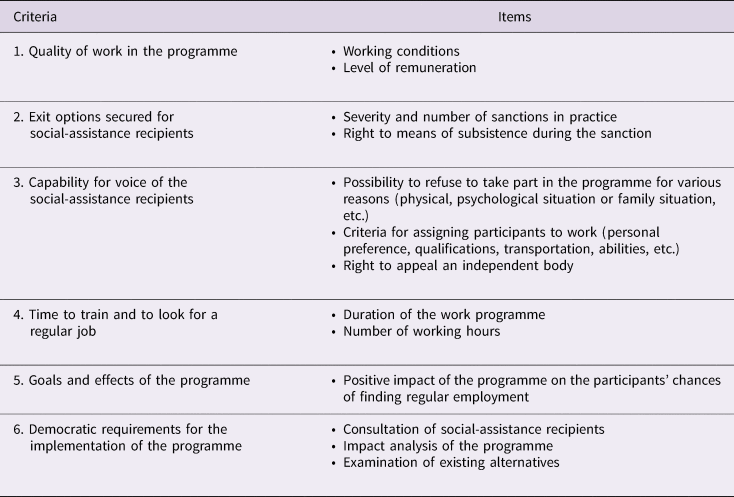

According to well-established case-law, states intending to adopt a measure that undermines the forced-labour prohibition or the right to freely chosen work are under a legal duty to respect the proportionality principle. However, human rights bodies do not make any explicit reference to this proportionality requirement when confronted with MWPs, or more broadly with coercive activation measures. Yet, an in-depth examination of the quasi-case-law of these bodies reveals that human rights bodies seek to achieve a proportionate balance between the objective pursued by the state through MWPs and the burden imposed on the recipients of social assistance. Aiming to work towards the systematisation of case-law in progress, we have classified the different elements pinpointed by international bodies into six general assessment criteria described below (Dermine, Reference Dermine, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020a).

3.1 Quality of work in the programme

International bodies link the protection of freedom in the work relationship with working conditions and remuneration (quality of the work). They consider that poor working conditions or remuneration may reveal that a job, despite formally expressed consent, has not been freely chosen. Consequently, they connect the prohibition of forced labour and the right to freely chosen work to labour rights. They realise that the latter are the concrete means of guaranteeing real freedom in the work relationship.

With regard to the obligation to perform work in exchange for social-assistance benefits, ILO bodies consider that it would constitute forced labour if the state were to take advantage of constraints on social recipients in order to make them accept working conditions that they would normally not accept.Footnote 4 In that sense, the CEACR explained that

‘if the allowance paid were to constitute an excessively low level of remuneration for the work involved, the scheme could be tantamount to exploiting constraints by offering people who had no other options, employment on terms that would not normally be acceptable.’Footnote 5

In addition, regarding the right to freely chosen work, the director general of the ILO noted that

‘the concept of “freely chosen employment” broadens the ILO's field of concern beyond the imposition of forced labour to encompass all those situations in which a worker's freedom of choice of employment is somehow constrained. Such situations may also involve other wrongs, such as infringement of labour legislation on wages, working time, or breach of the employment contract, while not necessarily amounting to the severe violation of human rights represented by forced labour.’Footnote 6

For its part, the CESCR, the monitoring body of the ICESCR, called on states, on the basis of the right to freely chosen work, to review their MWP legislation with a view to ensuring that it complies with labour standards, including the minimum wage.Footnote 7

3.2 Exit options secured to social-assistance recipients

International bodies also show deep concern regarding the ability of social-benefit recipients to opt out of MWPs (exit options),Footnote 8 namely refusing to take part in the programme, which depends on the financial consequences attached to it. In order to examine the availability of exit options, they request states to specify the sanctions provided for in the legislation for refusing to participate in the work programme, but they also ask for information on the level and number of sanctions imposed in practice.Footnote 9 Under this criterion, international bodies thus link freedom in the work relationship with the right to a minimum means of subsistence.Footnote 10 They realise that guaranteeing the means to lead a decent life in the event of withdrawal from the programme is an indispensable safeguard to protect the freedom of working welfare recipients in the work relationship. In this regard, the ECSR, the monitoring body of the ESC, considers, under Article 13 of the ESC (the right to social assistance), that the reduction, suspension or termination of social-assistance benefits of those recipients who fail to comply with the obligation to participate in an MWP should not deprive them of their means of subsistence. At least emergency assistance should stay available.Footnote 11

3.3 Capability for voice of the social-assistance recipients

With a view to guaranteeing a certain freedom of choice for social-assistance recipients within a programme that is based on a principle of mandatory participation, international bodies are also interested in letting social-assistance recipients have some influence in the process, namely the ability to negotiate and challenge the collective requirement to join an MWP.Footnote 12 First, supervisory bodies check whether the decision-makers’ discretion is marked by guidelines such as grounds for refusal to take part in the work programme (i.e. physical, psychological or family situation).Footnote 13 Second, they verify whether decision-makers are obliged to take into account certain criteria for assigning individuals to social utility work (preference, qualifications, physical and intellectual abilities, transportation, etc.).Footnote 14 Third, international bodies require that an independent body be able to review the decision of assignment in order to ensure that the decision-makers respect the guidelines and do not exceed their margin of appreciation or misuse it.

3.4 Time to train and to look for a regular job

Unlike the prohibition of forced labour, the right to freely chosen work not only protects the freedom within a work relationship; it also protects free and equal access to the labour market. Thus, the ECSR condemns under this right practices that would affect in a disproportionate manner free and equal access to the labour market. For example, it ruled that the civilian service imposed by the Greek government as an alternative to compulsory military service, although it could not be regarded as forced labour, may amount to a restriction on the right to freely chosen work by depriving the individual from accessing the labour market during the duration of the civilian service. In this case, the ECSR concluded that this duration was excessive and constituted a ‘disproportionate restriction’ on the freedom guaranteed by Article 1(2).Footnote 15 In our opinion, the right to freely chosen work may thus be infringed mutatis mutandis if the participation in an MWP takes up too much of the social-assistance recipients’ time and leaves them with insufficient occasion to train or look for a regular job. This would also be the case if the programme has an excessive duration.

3.5 Impact of the programme on reintegration into the labour market

Another criterion relates to the objective pursued by the introduction of an MWP and its effects on the chances of participants to later access regular employment. This does not mean that other objectives pursued by the states, such as the reciprocity principle, cannot be regarded as being of general interest. Instead, it implies that the positive impact of the measure on the participants’ chances of finding regular employment should be part of the proportionality test.Footnote 16

Under this criterion, supervisory bodies demonstrate their concern that the right to freely chosen work, namely the freedom dimension of the right to work (right as limit, obligations to respect), is connected with the other facet of the right to work, namely the right-to-work dimension of possibility (right as goal, obligations to fulfil). The supervisory bodies consider the extent to which the implementation of MWPs that temporarily restrict the free choice of employment of welfare recipients will later result in their reintegration into freely chosen paid employment and thus ultimately improves the realisation of their fundamental right to work.

3.6 Democratic requirements for the implementation of the programme

Lastly, supervisory bodies lay down democratic requirements for the implementation of any measure that restricts the enjoyment of social rights. In a review of the international case-law on social rights, three types of general procedural requirements can be identified that should be considered for the implementation of MWPs since they tend to restrict the enjoyment of the social right to freely chosen work, but also the right to social assistance (Dermine, Reference Dermine and Binder2020b). Before the implementation of a restrictive measure, those affected by it, namely the social-assistance recipients, must be consulted.Footnote 17 Supervisory bodies are therefore not only attentive to the capability for voice of social-assistance recipients under the MWP, but also upstream at the time of the democratic discussion on the adoption of such programmes, since they restrict the enjoyment of social rights. In addition, an analysis of impact and of existing alternatives should be carried out.Footnote 18 After the implementation of a reform, governments must then proceed to an impact analysis of the measure.Footnote 19

4 Applying the emerging human rights framework to the Dutch case

In order to specify the content of social rights, according to our experimentalist approach, this section focuses on the interaction between the evaluation criteria and law in action. For this purpose, we have studied how the obligation of social-assistance recipients to participate in MWPs has been implemented in the Netherlands (sections 4.2–4.7). We start with a brief introduction to the case of the Netherlands and to the empirical methodology used to describe the practices in the Netherlands (section 4.1). The main conclusions of the section are summarised in the last section (section 4.8).

4.1 Introduction to the Dutch case-study and methodology

In the Netherlands, the duty of social-assistance recipients to participate in MWPs was introduced in 1990. This was a consequence of a reform of the Social Assistance Act that transformed the acceptance of paid work as an eligibility criterion for the right to social-assistance benefits to an obligation.Footnote 20 The welfare office was now allowed to deploy various instruments for the reintegration of social-assistance recipients into paid work, among which was the obligation to participate in a non-paid-work programme.Footnote 21 Since 2004, the responsibility for the reintegration of recipients of social assistance has shifted from the central authorities to the municipalities.Footnote 22 And with the introduction of the Participation Act in 2015, the personal scope of the duty to reintegrate has been extended to include all single parents, irrespective of the age of their youngest child.Footnote 23

This section draws on empirical research conducted by one of the authors, Anja Eleveld, and addresses the most relevant outcomes with respect to each of the six human rights criteria identified by the other author, Elise Dermine. The empirical research was conducted between 2017 and 2018 in three Dutch municipalities: one municipality belonging to one of the four principal cities in the Netherlands with more than 300,000 inhabitants (‘municipality A’) and two medium-sized cities, with 50,000–100,000 inhabitants (‘municipality B’ and ‘municipality C’). The methods used in the study consist of semi-structured interviews with twenty-one municipal policy-makers and staff, thirty-one welfare officers (case managers), thirty work supervisors, seven members of client councils and forty-two participants (eighteen male and twenty-four female) of MWPs. In addition, almost forty-five interactions between recipients and the welfare officers were observed.

4.2 Quality of work in the programme

In the Netherlands, social-assistance recipients do not fall under the legal definition of ‘employees’. As a result, except for the Dutch Working Time Act and the Health and Safety Act, they are barely protected under (basic) national labour standards (Eleveld et al., Reference Eleveld, Harris, Højer Schjøler, Eleveld, Kampen and Arts2020). The Participation Act does not provide for alternative provisions in this regard. The case-study furthermore revealed that the investigated municipalities generally omit to fill these (basic) ‘employment protection gaps’, except for the right to annual leave, which is implemented in most MWP contracts. For example, recipients with care duties cannot rely on care rights stipulated for employees in the Employment and Care Act.Footnote 24 The fact that thirteen (out of twenty-four) female respondents and only five (out of eighteen) male respondents have care duties indicates that the absence of care rights mostly affects female recipients.

In view of the extension of the obligation to reintegrate to single parents, irrespective of the age of the youngest child, we specifically examined regulations and practices related to the protection of caregivers at MWPs. In this respect, it was striking that while employees are entitled to two weeks of annual paid care leave, there are no comparable national, municipal or contractual regulations for working social-assistance recipients. In fact, working welfare recipients depend on their work coach or work supervisor for being granted permission to take up care leave. While, in practice, recipients are often allowed to take days off in case of sick children, some welfare officers argued that organising a backup under these circumstances was part of the learning process of acquiring basic employee skills. Accordingly, these welfare officers said that they normally would refuse to grant care leave.

4.3 Exit options secured to the social-assistance recipients

The Participation Act stipulates that the municipality must impose a financial sanction when the recipient fails the duty to reintegrate. The sanction amounts to a reduction in benefits, of 100 per cent for one month, and a number of months in the case of recidivism. Those refusing to participate in an MWP thus risk a large reduction in their benefits.

These sanction regulations caused a lot of stress among recipients, particularly in municipality B where all recipients are subjected to the duty to participate in an MWP. Regarding the high sanctions, these recipients felt that they were deprived of any ‘exit options’. On one occasion, a single mother who did not have access to financed childcare had to ask all her family members and friends to babysit her daughter during the hours that she attended the MWP. This recipient had not been able to send her daughter to professional day care because the tax credits that she was entitled to receive for day care would be withheld by the tax authorities in order to repay her debts to them. Another interviewed recipient suffering from a similar problem with the tax authorities took her four-month-old daughter with her to the MWP.

As we have seen, the duty to safeguard exit options for social-assistance recipients also entails the duty to offer access to minimal means of subsistence to sanctioned recipients. This means that we should also consider the regulation and implementation of so-called ‘mitigation clauses’. The Participation Act stipulates that a sanction can be reduced in case of hardship (i.e. hardship clause)Footnote 25 and annulled in case the recipient decides to fulfil her obligations (i.e. reparatory clause).Footnote 26 The research data suggest, however, that once a sanction is imposed, it is almost never mitigated by one of these clauses because sanctioned recipients – and many welfare officers as well – are often unaware of the mitigating regulations. Furthermore, where welfare officers knew about a hardship or reparatory clause, they turned out to be rather sceptical about these measures. They argued that they would impose a sanction only when they had tried all other means to convince the recipient to co-operate with work-related obligations. And after all the paperwork they had done to prove the recipient's fault, it felt like a detour to offer hardship benefits or restitution. In sum, the case-study suggests that social-assistance recipients who are obliged to participate in an MWP are, in practice, deprived of any real exit options.

4.4 Capability for voice of the social-assistance recipients

The capacity for voice implies that the welfare office should take personal circumstances and preferences into account when considering assigning a person to a particular MWP. According to a decision of the Dutch Higher Appeal courts, the municipality must take account of the personal situation of the recipient.Footnote 27 More recent case-law shows that this guideline should be broadly interpreted. For example, municipalities are free to refer educated recipients and recipients with recent work experience to unskilled MWPs.Footnote 28 The case-study reveals, in this regard, that the extent to which personal preferences are taken into account first and foremost depends on the efforts of individual welfare officers to find a tailored MWP. Good intentions can, however, easily be offset by commercial considerations. For example, all three municipalities have concluded contracts with private companies to either deliver a certain number of recipients to work with them or to produce certain goods for them. In order to meet the contractual obligations, welfare officers contended that most of the time, they assign recipients to one of these private companies or to other public programmes that produce goods for these private companies. These standard available MWPs usually entail simple unskilled work, such as gardening, serving coffee in a nursing home, production work and delivering mail.

At the policy level, we also observed some good practices that – at least theoretically – enable the capability for voice of individual recipients, namely the requirements: (1) to use contracts, provided that these had the character of a mutual agreement; (2) to use learning goals; and (3) to evaluate the participation at the MWP. For example, the formulation of learning goals enables participants in MWPs to exercise influence on the nature of their work and the supervision that they will require, and – if necessary – to refuse their participation in MWPs failing to contribute to achieving their learning goals. In addition, the requirement to evaluate an MWP provides recipients with the opportunity of sharing their experiences and their point of view on the work activities and eventually to also propose changes in the way in which are supervised or to ask for alternative work activities.

Some social-assistance recipients reported that they highly appreciate the implementation of learning goals and evaluation moments. They felt that these measures had helped them to develop themselves at the MWP and had increased their self-confidence. Yet, often contracts, learning goals and evaluations fail to be implemented in effective ways. For example, instead of formulating individual learning goals, welfare officers (and work supervisors) often use the same very basic learning goals for each recipient, such as ‘learning basic worker skills’, irrespective of the numbers of years of work experience or the education level of the concerned person. In addition, official evaluations that enable recipients to share their experiences with the welfare officer or work supervisor are frequently skipped. Furthermore, instead of mutual agreements, municipalities have drawn up the contract unilaterally and, accordingly, these ‘contracts’ are often viewed as documents stipulating recipients’ duties. In sum, in the absence of an effective system monitoring the implementation of these measures, social-assistance recipients very much depend on the qualities and intentions of their work officer.

The final aspect of the capability for voice entails access to appeal decisions. In the Netherlands, this is regulated in the Administrative Act, which provides the possibility to draw up a ‘notice of objection’ and to lodge an appeal or complaint against a municipality. However, the case-study reveals various practical obstacles preventing recipients from using these legal measures.

First of all, recipients do not legally object against a referral to a specific work programme because they are not aware of objection as a possibility. Amongst other things, this is due to the fact that these recipients do not receive a separate ‘decision letter’ explaining the possibility of appeal against the municipal decision. In one municipality, the policy officer admitted that the municipality deliberately refrained from issuing an official decision in order to prevent people from drafting a notice of objection.

Second, welfare recipients who refuse to go to the MWP are usually well aware of their right to lodge an appeal against the financial sanction imposed on them. But still some recipients expressed the view that lodging an appeal would be futile since they would never win a case against the municipality. For the same reason, recipients reported that they would not lodge a complaint against the way in which they were treated by welfare officers or work supervisors. Hence, their perception of the municipality as a powerful authority constitutes an important obstacle for initiating legal action against the municipality.

Finally, interviewees argued that recipients would refrain from lodging official complaints against welfare officers or work supervisors out of fear of disturbing the relationship with these officers on which they depended. For example, curiously, the official complaint committee in municipality B had only received a handful of complaints (which were all rejected), while the client council produced a ‘black book’ filled with dozens anonymous complaints of recipients about the way in which they were treated by welfare officers who referred the recipient to MWPs.

4.5 Time to train and to look for a regular job

In the absence of a provision in the Participation Act, all investigated municipalities determine the maximum length of the MWP in municipal regulations. Yet, in practice, the periods for which people perform these activities can be much longer than the period of six to nine months mentioned in the municipal regulations. For example, in one of the investigated municipalities, it is not unusual for recipients to work for several years in an MWP.

In addition, none of the municipalities regulates the maximum weekly working hours. In practice, the weekly working hours vary from a few hours to forty hours in the week. The number of hours is usually tailored to the situation of the recipient. For example, in all municipalities, welfare officers are willing to take account of the school hours of the recipients’ children. However, regarding the assigned number of working hours, welfare officers often fail to take recipients’ other duties into account, such as informal care for other family members and volunteer work. In practice, almost half (eighteen) of the interviewed recipients perform care tasks – often one to two days a week – in addition to their work at the MWP. Concretely, this situation leaves them scarcely any (or no) time for training and looking for a regular job.

4.6 The goals and effects of the work programme

According to our human rights framework, MWPs should aim at the reintegration of recipients into paid work. However, since none of the three municipalities systematically investigates the effects of work placements on the sustainable transition to regular jobs, it is impossible to draw any objective conclusion in this respect. From a subjective viewpoint, the effects of MWPs were doubted among both interviewed recipients and welfare officers. For example, a large number of the recipients held that they were not learning anything at the MWP. This was partly due to the fact that almost all MWPs aim at the development of general worker skills, such as ‘being on time at work’ and ‘listening to a boss’. In addition, interviewed welfare officers held that learning general worker skills is not enough for (sustainable) job transitions. In their opinion, MWPs hardly result in job transitions because of the characteristics of the participating recipients (long-term unemployed, low education, insufficient proficiency of the Dutch language, insufficient motivation) and the characteristics of the labour market (high labour-market demands on workers, age discrimination, etc.).Footnote 29 Some officers even admitted that on some occasions MWPs are used as a kind of punishment (cf. Hatton, Reference Hatton2018). This suggests that exit options are restricted not only because of the sanctioning system (see section 4.3), but that this is also due to the ineffectivity of MWPs to increase the opportunity for job transitions. Moreover, on some occasions, recipients stay for several years in MWPs, despite municipal provisions setting the maximum length of participation in MWPs (see section 4.5).

4.7 Democratic requirements

According to our human rights framework, the implementation of an MWP should be preceded by consultation with the parties concerned by the measure, namely the recipients of social assistance. When MWP regulations and policies are mainly developed at the municipal level, such as in the Netherlands, client councils are potential important democratic fora (Barnes et al., Reference Barnes, Newman and Sullivan2007; Dean, Reference Dean2010; Bonvin, Reference Bonvin, Rogowksi, Salais and Whiteside2011).

The Participation Act stipulates the installation of a client council to advise the municipality on municipal regulations and policies.Footnote 30 However, it leaves the municipality free not to install a client council and/or to involve only representatives of recipients of social assistance (e.g. workers at a food bank, a social worker) but not the recipients of social assistance themselves. The case-study disclosed that only municipality A has installed a client council consisting entirely of social-assistance recipients; the client council in municipality B consists largely of people who are not social-assistance recipients; and there is no client council in municipality C.

In municipality A, social-assistance recipients are genuinely involved in policy-making processes. For example, it advises the municipality on several subjects, such as the provision of travel costs to MWPs and the treatment of social-assistance recipients at MWPs. The client council also organises meetings periodically with council members of all political parties to inform them about the experiences of social-assistance recipients. At the same time, the client councils in both municipalities A and B admitted that it was difficult to recruit people capable of understanding the policy documents and to organise themselves so as to successfully affect municipal regulations and policies. In addition, these client councils argued that they had been struggling to recruit sufficient members representing all social-assistance recipients. For example, while a great number of the participants of MWPs consists of females and individuals with a migration background, the client council predominantly consists of older White males, a result of which is that the interests of specific groups are insufficiently represented. Hence, in addition to the weak national legislation, the case-study suggests that due to practical difficulties, social-assistance recipients are insufficiently involved in the implementation of MWPs.

4.8 Conclusion

The case-study exposed the fact that Dutch national law leaves a lot of leeway to municipalities, the regulations, policies and practices of which are not in line with the human rights framework. Working recipients are insufficiently protected by basic labour standards. The time limits of the work programmes set by the municipalities are not strictly followed and/or are unknown. Sanctions are almost never mitigated. The effects of MWPs are not systematically evaluated. Recipients (and welfare officers) felt that the programmes do not contribute to paid-work transitions and recipients sometimes stay in the MWP for several years.

Besides, measures aimed at enhancing the capability for both individual and collective voice partly compensate for deviations from minimum human rights standards. However, in practice, the capability for voice of social-assistance recipients is impeded in various ways. This is due to: (1) commercial interests; (2) an insufficient or unilateral (instead of dialogical) implementation of instruments aiming at enhancing the capability for voice; (3) insufficient (practical) access to legal appeal and complaint procedures; and (4) the absence and at times infectivity of client councils.

Lastly, the case-study shows that MWP law, regulations and policies have a negative effect on the position of caregivers (mostly women). First, working social-assistance recipients with care duties do not have access to care-leave rights. Second, the amount of time spent on informal care work is mostly ignored when the duty to work is imposed. Third, caregivers are obliged to work in MWPs even when they cannot not obtain professional day care for their small children. And, finally, they are insufficiently represented in the client council. Although the case-study does not draw on a representative sample, this difference in caregiving activities between male and female respondents reflects the unequal distribution of care work between men and women in the Netherlands (Verbeek-Oudijk et al., Reference Verbeek-Oudijk, Roeters and de Boer2018).

5 Elaborating the human rights framework on some practical issues emerging from the case-study

In section 2, we explained that the experimentalist approach favours a procedural model in which national states can deviate from minimum standards set by international bodies under human rights if they can justify that they may better realise human rights using alternative measures. Furthermore, in this approach, international bodies are invited to complement the minimum human rights standards, based on the practical experience of states, in order to increase the effective realisation of rights. In this section, we draw lessons from the confrontation of the human rights framework with the practice of the Netherlands and propose some adaptations to the framework.

First of all, the case-study has shown that, in the absence of legal guarantees safeguarding substantive minimum standards for MWPs (i.e. quality of work, exit options, time to train, goals and effects), the capability for voice of working welfare recipients is a key criterion to the human rights framework. In addition, the case-study suggests that procedural safeguards need to be added to the human rights framework in order to secure the capability for voice. These procedural safeguards are further elaborated upon in section 5.1.

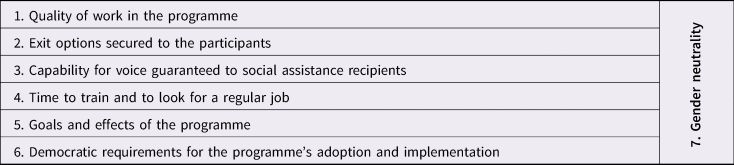

In addition, the case-study has revealed that municipalities often fail to consider the fact that some social-assistance recipients assume care tasks. Given the gendered distribution of roles, mainly women encounter particular difficulties with MWPs. In this regard, the gender neutrality that the Dutch MWP appears to presume seems problematic. We therefore propose in section 5.2 to add a cross-cutting criterion of gender mainstreaming to the human rights framework in order to take into account, at the level of each assessment criterion, the differences between women and men regarding their assigned roles, specific conditions and needs, and their enjoyment of rights.

5.1 Developing the capability for voice of the working welfare recipients through procedural rights

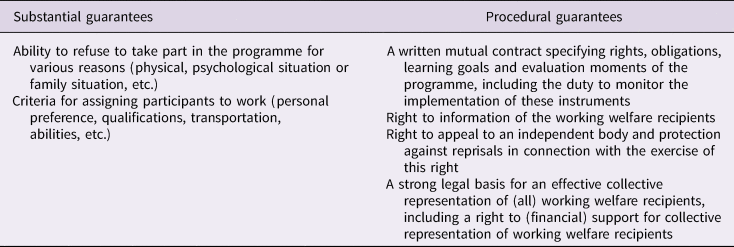

The case-study demonstrated that the recognition of a right to appeal an independent body is neither sufficient (as a procedural safeguard) to ensure that legal action is actually taken, nor does it secure the capability for voice of working welfare recipients. In light of the experience of the Netherlands and in accordance with the experimentalist approach in determining the content of rights, we propose to supplement this human rights criterion with four procedural guarantees aimed at effectively securing capability for voice: (1) imposing a written contract specifying the rights and obligations of the working welfare recipients and the duty to monitor the implementation of these measures; (2) securing their right to information; (3) introducing protection against reprisals if a complaint is filed with the municipality or legal action taken; (4) developing the collective representation of working welfare recipients towards the municipality as well as in the private company where they are sent to work or for which they produce goods.

These procedural guarantees of the capability for voice can be distinguished from the substantial guarantees identified in Table 1 (see section 3). They are necessary to prevent and combat abuses (gaps between law and practice) and to contribute to the gradual building-up of a legal social status protecting working welfare recipients that is currently lacking in national states. The four procedural safeguards of the capability for voice are further developed in this section.

Table 1. The emerging international human rights framework for assessing national MWPs

5.1.1 Imposing a written contract specifying the rights and obligations of the working welfare recipient

Based on the case-study, we suggest the use of written contracts specifying the rights and obligations of the working welfare recipient under the MWP. These contracts should not be drawn up unilaterally. Instead, social-assistance recipients must be involved on an equal basis in the drafting of the contract. For this purpose, they could be assisted by a representative of the client council (see section 5.1.4).

The use of written contracts – as procedural rule – will contribute to the better realisation of various criteria of the human rights framework. In the first place, they elucidate how the voice of the recipient is to be respected (third criterion, i.e. the capability for voice). To this end, the contract should, amongst other things, stipulate individual learning goals and evaluation moments. Related to this, it should also ideally contain the nature of the activities (stipulating what the recipient will be doing in order to achieve the learning goals) and a timeline (stipulating when the recipient will have reached the individual learning goals). In the second place, contracts can regulate and/or clarify which aspects of employment law are applicable to recipients of social assistance, in particular in the absence of specific regulations applicable to working welfare recipients (criterion, i.e. the quality of work in the programme). As such, a written contract also functions as a source of information (see section 5.1.2). In the third place, standard contracts can stipulate the maximum duration of the obligation to work, which is also relevant to the fourth criterion of our human rights framework (i.e. time to train and to look after a regular job). Finally, written contracts – like an employment contract – can regulate the power relationship between the parties: they provide a legal basis on which to take legal action in case of non-compliance with the provisions of the contract and can be helpful to prevent abusive practices (Eleveld, Reference Eleveld, Blackham, Kullmann and Zbyszweska2019). And even if the contract has been drawn up unilaterally or contains illegal or abusive clauses, it may also be important in order to be able to take legal action not on its basis, but against it, claiming its illegality under higher standards (such as labour law, social security law, fundamental rights or even contract law).

While the use of contracts (including learning goals and the requirement for evaluations) may be necessary to ensure human rights protection, the case-study demonstrated that this alone is not sufficient. That is, there should be a supervisory system in place to monitor whether contracts are rightly implemented. These could be ‘discursive arenas’ in which officials discuss the implementation of learning goals in collegial bodies, for example, or within client-participation procedures (see further section 5.1.4) (also see Dzur, Reference Dzur2008; Molander et al., Reference Molander, Grimen and Odvar2012, pp. 225–226).

5.1.2 Securing the right to information for working welfare recipients

The case-study indicates that working welfare recipients are often unaware of their rights, such as, for example, the right to invoke hardship or to repair a sanction. Securing the right to information helps to reduce the gap between law and social practice. The right to information is also important to ensure access to justice. We observed in the case-study that several working welfare recipients did not know that they also had the power to object to a specific referral to a MWP, for example to an unattractive programme by way of a sanction. Our empirical observations are consistent with the recent literature on the non-take-up of rights (Warin, Reference Warin2016; Van Mechelen and Janssens, Reference Van Mechelen and Janssens2017). On the one hand, lack of awareness is one of the main factors explaining the phenomenon of the non-take-up of rights. On the other hand, once institutions know that there is no risk of legal action against them, it is difficult to combat the development of illegal practices and – as result – to prevent a widening gap between law and practice.

Raising awareness involves organising collective information sessions, drafting written contracts (see section 5.1.1), delivering written decisions and writing all types of documents in plain and accessible legal language for audiences often far removed from the law. This is all the more important given the discretionary power of the welfare officers and the vulnerability of social-assistance recipients. While it is up to the welfare officers and/or municipalities to implement the necessary measures to realise the right to information, collective representative bodies can also be an important channel for informing working welfare recipients of their rights towards the municipality and private companies to which they are eventually sent to work. This point will be further developed in section 5.1.4.

5.1.3 Introducing protection against reprisals in case of complaint or judicial action

Although properly informed of their rights, we observed that some beneficiaries do not file a complaint or take legal action because they fear that this will have a negative impact on their relationship with the municipality and on the allowances on which they (and their families) depend. In order to ensure that working welfare recipients dare to oppose a decision of the municipality, it would be appropriate to attach to this right protection against any form of reprisal, be it a financial sanction on the social-assistance benefits or any other adverse treatment.

This protection could be modelled on non-victimisation clauses in equal-treatment law. Thus, if a working welfare recipient is sanctioned or suffers adverse treatment after having filed a complaint or taken legal action, the municipality would have to prove that this treatment was unrelated to the introduction of the complaint or legal action. Otherwise, it would have to compensate the social-assistance recipient and restore their rights. It is also essential that recipients are adequately informed about these rights (see section 5.1.2).

5.1.4 Developing collective representation for working welfare recipients

Regarding the absence of consultation with social-assistance recipients in policy-making processes and the obligation to evaluate MWPs, the case-study reveals the need for strong and effective client councils consisting of recipients in order to fill in the sixth criterion of our human rights framework (i.e. democratic requirements for the adoption and implementation of the programme). Client councils could monitor evaluations on the effectiveness of MWPs and discuss the outcomes with the democratic representative bodies (in the Dutch case, the local council) deciding on the policies of the MWP. They could also become more involved in policy-making processes.

Moreover, client councils could monitor the implementation of individual contracts (see section 5.1.1). They could further urge the administrative body to notify recipients about the option of invoking a hardship clause during a hearing and the existence of protection against reprisals in case of complaint or judicial action (see sections 5.1.2 and 5.1.3).

The case-studies suggest that a strong legal basis and financial support for training, for example, and an official secretary are preconditions for realising effective client councils. Besides, collective representation of workers’ interests is not only important within the municipal administration. Another way of achieving adequate workers’ protection is to ensure the collective representation of workers in enterprises in which they are sent to work under MWPs. In case recipients work together with regular workers for a private employer, regular workers (and their trade union) may have an interest in involving recipients in collective actions as ‘unremunerated work’ conducted by recipients may result in crowding out regular workers, which has a dampening effect on the actual number of job transitions (Shildrick et al., Reference Shildrick2012) or the levelling-down of employment protection. In addition, collective action in collaboration with regular employees may affect municipal practices, as seen in the case-study, such as giving priority to commercial considerations over recipients’ preferences and abilities when assigning recipients to a MWP. In this respect, we notice that ILO Convention No. 87 on the right to organise applies to ‘workers’, which, according to the Committee on Freedom of Association, also includes workers involved in community participation programmes to combat unemployment.Footnote 31

Table 2 indicates both substantial guarantees for the capability for voice identified in Table 1 and the corresponding procedural guarantees developed in this subsection.

Table 2. Completing the human rights criterion of the capability for voice of the working welfare recipients by procedural guarantees

5.2 Making the human rights framework gender-sensitive

The case-study reveals that recipients were treated in (almost) similar ways, irrespective of their caregiver role. This reflects a broader policy trend that emphasises the necessity for all people to be engaged in paid employment (productive work) without considering the need for people providing (unpaid) care work (reproductive work) (Weeks, Reference Weeks2011; Adkins, Reference Adkins2012). Whereas unemployment used to be understood as a period detached from productive work, it tends to be seen in post-Fordist economies as a period on a continuum with paid employment that must be spent in productive activities, ranging from training, internship or unpaid work programmes (Adkins, Reference Adkins2012). However, given that women, whether employed or unemployed, are also involved in caring tasks (reproductive activities) to a much greater extent than men (for the Netherlands, see Verbeek-oudijk et al., Reference Verbeek-Oudijk, Roeters and de Boer2018; further, see OECD general data on time use by sex, https://stats.oecd.org/), ignoring this situation and not adapting MWP policies to the situation of people who are involved in care tasks risks creating new socio-economic inequalities between women and men.

As several feminist authors have argued, all individuals are dependent on other people during some part of their lives and caretakers themselves depend on economic and institutional resources to provide care (Fineman, Reference Fineman2004; Busby, Reference Busby2011). Regarding this ‘inevitability of dependency’, the argument could be made that social-assistance recipients who are caregivers should not be subjected to MWPs. A less radical solution entails the granting of specific rights to social-assistance recipients who are caregivers, such as the right to refuse to be sent to an MWP (gender mainstreaming action on the third criterion, i.e. capability for voice – substantial requirements) in case they are not sufficiently facilitated regarding their care tasks (e.g. support of the administrative body to find day care). Other additional rights would include extra days off in order to care for a sick child (action on the first criterion, i.e. quality of work) and the right to work fewer hours in order to have sufficient time left to look for a job (action on the fourth criterion, i.e. ‘time to train and to look for a regular job’). Furthermore, the client council or municipality should have a best-effort obligation to include caregivers such as single parents in the client council (action on the third criterion, i.e. ‘capability for voice – procedural requirements’).

Our empirical observations seem to be supported by ILO Convention, 1981, No. 156 on workers with family responsibilities, which promotes the accommodation of workers who are caregivers.Footnote 32 According to the CEACR, the supervisory body of the ILO Conventions, the reference to ‘the worker’ was intentional, so as to cover all workers.Footnote 33 By analogy, we may assume that this Convention has the same scope of application as ILO Convention No. 87 on the right to organise (see previous subsection).

Our empirical observations in conjunction with ILO Convention No. 156 thus plead for the addition of a transversal criterion of gender mainstreaming to the emerging international human rights framework for the evaluation of MWPs (see Table 3). This transversal criterion implies verifying the impact of the introduction of an MWP on gender inequalities, at the level of each of the six criteria previously identified.

Table 3. Adding a transversal criterion of gender neutrality to the international human rights case-law

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we have adopted an experimentalist approach to determining the content of international human rights for assessing national MWPs that are progressively developing in an extensive number of industrialised countries. This approach implies going back and forth between law and practical experience in order to determine the best way to secure human rights in an ever-changing environment.

First, we have identified in the soft case-law of international bodies six criteria for evaluating MWPs that develop within states: (1) quality of work in the programme; (2) exit options secured for social-assistance recipients; (3) capability for voice; (4) time to train and to look for a regular job; (5) goals and effects of the programme; and (6) democratic requirements for the implementation of the programme.

We have then confronted this emerging international human rights framework with the practice of the Netherlands. Empirical research in Dutch municipalities has shown that the capability for voice of working welfare recipients (criterion (3)) is an essential issue for the progressive development within states of a protective social status for these atypical and vulnerable workers. For assessing this criterion, attention should be paid to four procedural items: the use of individual and written contracts, including the duty to monitor the implementation of these measures; proper information on rights and duties; protection against reprisals in case of complaint or legal action; and the collective representation of working welfare recipients. In addition, we have shown that the implementation of MWPs raises in practice gender issues, related to the fact that these programmes assigning women to productive activities are often added to the performance of reproductive activities within the family and for relatives. We therefore argued that the human rights assessment framework should be complemented by a seventh cross-cutting criterion of gender mainstreaming.

By including these aspects in our human rights framework, we have intended to construct an evaluative instrument that is suitable for the practical evaluation of national MWPs while at the same time offering solutions to comply with the prohibition of forced labour and the right to freely chosen labour. Finally, as we hoped to have demonstrated, this human rights framework is not fixed, but open to further refinement and alteration when applied to the law in context.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NWO (the Dutch Research Council) under (Veni) Grant number 451-15-005. The author would like to thank the two reviewers for their comments on this article.