Introduction

Few Old Master paintings possess as turbulent an object history as the Ghent altarpiece by the Van Eyck brothers, completed in 1432 and now restored, since World War II, to the city’s cathedral for which it was made. From the tableau vivant performed in its image in 1458 to mark the visit of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, to Ghent, to the work’s looting by Napoleon and Hitler, the altarpiece has been placed continuously in the service of civic pride and nationalist politics for six centuries. Yet the polyptych has also served for a long time as one of those much-mythologized works of art that appear to stand outside history as universal measures of human achievement. Popular accounts of it dwell on its many trials, especially the altarpiece’s theft by the Nazis in 1942–45, when it was hidden in 1944 along with over 6,500 other artworks in the salt mines of Altaussee in Austria.Footnote 1 Even before this time, two panels of the altarpiece were stolen from the cathedral in 1934, one of which is still missing today. The theft informed Albert Camus’s novel The Fall, in which the protagonist harbors the panel of the Just Judges in his apartment while reflecting upon his own morality.Footnote 2

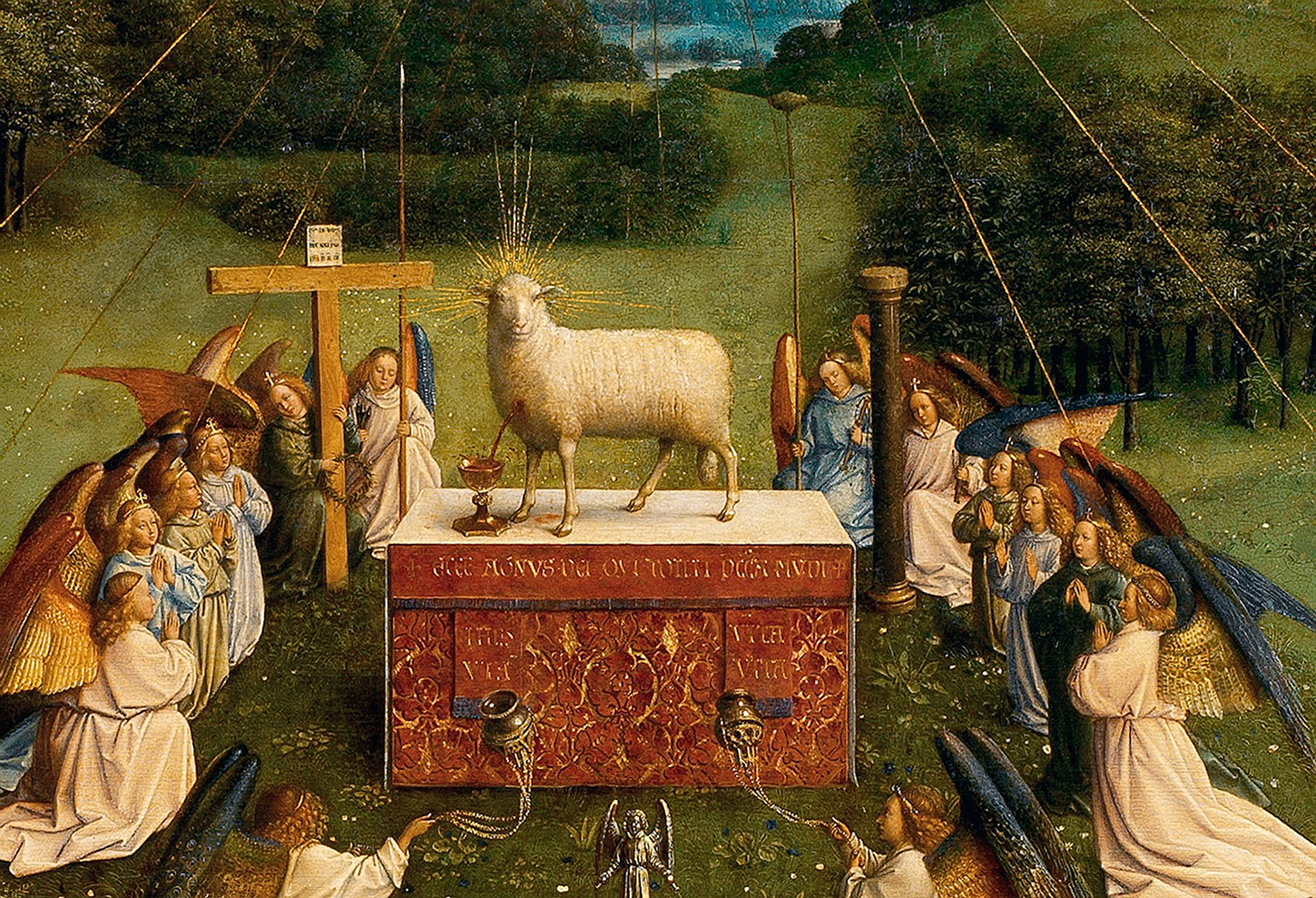

The Ghent altarpiece is a foundational work of art in the Western tradition (see Figure 1). A large polyptych made up of 20 individually painted panels, its wings open to reveal a scene in which groups of figures including saints, pilgrims, prophets, knights, and philosophers come forward to worship the Lamb of God, who stands upon an altar in a brightly colored meadow. The sacrificial Lamb, symbolic of Christ’s crucifixion, is framed by the colossal figures of the Virgin Mary, God the Father and John the Baptist, who are painted in lifelike material splendor on individual panels above. Images of music-making angel choirs and Adam and Eve complete the upper register of the inner view. Scenes of the Annunciation – the angel Gabriel’s visit to Mary, set in a vivid northern medieval cityscape – and the portraits of the donors, grace the outer, closed wings. The exquisite workmanship of the altarpiece, and its reputation as the earliest known landmark in the history of oil painting, has fostered admiration for it from its own day to the present. In 1521, the German Renaissance painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) recorded his visit to the painting, while two celebrated painters from the Low Countries, Lancelot Blondeel (1498–1561) and Jan Scorel (1495–1562) are reputed to have kissed the altarpiece “in many places” when they were entrusted with its cleaning in 1550.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Jan (c. 1390–1441) and Hubert (c. 1366–1426) van Eyck, The Ghent Altarpiece, Cathedral of Saint Bavo, Ghent, 1432 (courtesy of Lukas, Art in Flanders, VZW / Bridgeman Images).

The work’s great fame has also prompted repeated attempts to remove it, or parts of it, from its setting in Ghent and into the hands of covetous would-be owners. In 1578, protestant Calvinists took down the altarpiece with a view to presenting it to Elizabeth I, queen of England, whose agent made the journey to Ghent before the plan was curtailed. In 1794, the four central panels were taken by Napoleon’s troops to the Louvre palace in Paris for public display, only to be put back in place in Ghent, without the wings, in 1816. Next, the wings were sold the same year to an art dealer (without the Adam and Eve panels, which were removed into storage during the eighteenth century on the grounds of their nudity) from whom the wings passed into the collection of the king of Prussia. They were only returned from the Berlin Museum to Ghent with the Treaty of Versailles in 1920.Footnote 4 We now know that Adolf Hitler intended to “return” the altarpiece to the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin for this reason.Footnote 5 It is usually assumed that the altarpiece was destined for the Linz Museum along with the other high quality works of art hidden at Altaussee. The Sonderauftrag (special commission) Linz was Hitler’s project to erect a vast “super-museum,” which was planned but never realized, in his birth town on the Danube. His was not the only shopping list. Prior to World War II, during the 1930s, the American collector Andrew Mellon (1855–1937) reputedly offered 10 million dollars for the altarpiece.Footnote 6 Mellon was the donor behind the founding of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, which opened in 1941.

While much has been written on the altarpiece from the longue durée perspective,Footnote 7 this article will examine instead the little-known story of what happened to the Ghent altarpiece on its return to Belgium after World War II. Particular emphasis will be placed on the run up to the major conservation of the work led by Paul Coremans (1908–65) in 1950–51, when the altarpiece became the focus of a picture-cleaning controversy on its removal from Ghent to the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels. The article will trace the painting’s elevation to cultural icon in Belgium in the aftermath of the war and its particular significance for those in the north of the country. Making a close examination of the newspaper coverage of the proposed restoration in 1950, the article seeks to demonstrate that even the most instrumental care of artworks is rarely divorced from nationalist and political ideologies.

Restitution

The altarpiece was given special treatment almost immediately during the evacuation of Altaussee by the Allied Forces and the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives division (MFAA or Monuments Men). It was the first work of art to be repatriated to its country of origin through the Munich Central Collecting Point, from where it was flown by airplane to Brussels on 21 August 1945.Footnote 8 Popular accounts of the altarpiece’s theft and return, permeated with the language of a rescue narrative, treat the altarpiece’s status as a natural fact – as a form of natural selection even – as if the restitution took place in unspoken acquiescence with some universally recognized hierarchy of greatness. According to newspaper reports, however, the truth was more political and involved a strong intervention by the American ambassador to Belgium under Franklin D. Roosevelt, Charles W. Sawyer (1887–1979), who exerted pressure on behalf of the Belgians for the altarpiece’s prompt return.Footnote 9

Certainly, we know that the operation was carried out under instruction from Dwight Eisenhower as Allied commander, with the transportation costs funded by the US government. Thus, the altarpiece was the first object to be returned as a “token restitution” to the countries occupied by Germany during the war.Footnote 10 Group shipments of other objects from the Munich Central Collecting Point to Belgium, France, and the Netherlands followed in September and October 1945.Footnote 11 The second restitution to Belgium – a delegation that took place this time by road, leaving Munich on 22 September 1945 – contained other looted works such as Michelangelo’s sculpture, the Bruges Madonna (1501–4), 11 paintings from the Church of Our Lady in Bruges, and Dieric Bouts’s triptych of The Last Supper (1464–68) from Leuven. This handing back of property to Belgium marked another “first” – namely, the first instance where a home nation came to the Munich Central Collecting Point to receive its property.Footnote 12 Belgium’s delegate was the head of the laboratory of the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels, Paul Coremans, who will be discussed in more detail later in this article.Footnote 13 Coremans set a precedent. France and Holland followed suit, sending their own representatives to Munich on 27 September.Footnote 14 Already, however, a special relationship between Belgium and America was forming around the symbolic power and ownership of art.

The Ghent altarpiece was delivered by the Americans to the Royal Palace in Brussels on 22 August 1945. After the Belgians signed a receipt for it,Footnote 15 and it was examined by the art restorer Jef Van der Veken (1872–1964),Footnote 16 the painting was ceremonially displayed in a lavish reception room with piles of laurel leaves gathered below it to denote a status of the highest order (see Figure 2). The visual language of the display was grand in gesture, heaping its own layers of meaning upon the work of art. The symbolism of the laurel – of victory and, in Christian iconography, of the resurrection – evoked a script perfectly suited to an artwork that had undergone its own apotheosis through its safe delivery from the Nazis by the largely American personnel of the MFAA. An official handover was held in front of the altarpiece on 3 September 1945, when the American ambassador Charles Sawyer formally returned the work into the safekeeping of the regent, Prince Charles (1903–83), Belgium’s royal head of state.

Figure 2. Photograph of The Ghent Altarpiece on display in the Palais Royal, Brussels, September 1945 (courtesy of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, Brussels / KIK-IRPA).

A further Americanist gloss was added to the proceedings by the delegation to Brussels for the event of three of the most senior figures of the MFAA responsible for art restitution. These were Lieutenant Colonel Mason Hammond (1903–2002), Captain Calvin S. Hathaway (1907–74), and Major Louis Bancel LaFarge (1900–89), the chief of the MFAA for the Office of Military Government in the American Zone, who oversaw the operations of the Monuments Men in the field.Footnote 17 Of all of these agents, LaFarge’s presence at the handover of the altarpiece was particularly important because he had been instrumental – alongside commanding officer George L. Stout (1897–1978), who was the real “Frank Stokes,” George Clooney’s character in the film The Monuments Men (2014) – in the evacuation of Altaussee and the creation of the Munich Central Collecting Point.Footnote 18

Official photographs in the archives of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Brussels (Koninklijk Instituut voor het Kunstpatrimonium [KIK-IRPA]) show that a few days later, on 6 September 1945, the altarpiece provided a backdrop in the Palais Royal for an event of even more symbolic significance, a chapter in the altarpiece’s history not hitherto recorded. A reception was held in front of the painting by the Belgian government to mark the visit to Brussels of General Eisenhower and his military chief-of-staff in Europe, General Walter Bedell Smith (1895–1961).Footnote 19 In front of the picture, Smith was decorated with the Belgian Order of the Crown by Leo Mundeleer (1885–1964), the minister for national defence, in the company of Charles Sawyer, Belgium’s American ambassador, and Achille Van Acker (1898–1975), the Belgian prime minister (see Figure 3).Footnote 20 Eisenhower had already been awarded Belgium’s War Cross in July 1945. The altarpiece was not merely scenery in this context, then, but a highly resonant receptacle endowed with multiple meanings and representations regarding Belgian national identity and pro-American relations in the aftermath of World War II. Once a symbol of Nazi appropriation, the reclaimed altarpiece now functioned as a sign not just of restitution but also of reparation – of Belgian payback for the horrors of war and the blood spilled during the Nazi occupation.

Figure 3. Photograph of the reception in the Palais Royal, Brussels, 6 September 1945 (from the Van Eyck Dossier, KIK-IRPA, courtesy of the Belgian Ministry of Information [INBEL]). From left to right: Charles Sawyer, American Ambassador; Leo Mundeleer, Minister for National Defence; General Dwight D. Eisenhower; Achille Van Acker, Belgian Prime Minister in 1945; and General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s military chief-of-staff in Europe.

The staging of Eisenhower’s presence beside the rescued panels overlaid them with a further narrative, of the American liberation of Belgium, with the altarpiece as its cipher. The depth of this symbolism should be seen in the context of the scale of American blood shed on Belgian soil during the war. US army reports remind us that the Americans suffered over 89,000 casualties (including those missing or killed) during the Battle of the Bulge in the Ardennes region of Belgium under German attack in the winter of 1944–45.Footnote 21 The American cemetery and memorial at Ardennes, where many of those casualties are buried, holds the graves of 5,162 servicemen in over 90 acres of ground.Footnote 22

It is worth considering that the iconography of the altarpiece took on added significance in this postwar setting. One sees in this light the peculiarly apt nature of the Ghent altarpiece as a symbol following the war, in which the sacrificial lamb that stands bleeding upon the altar at the center of the painting becomes a sign not just of the crucifixion, in art-historical terms, but also of the sacrifices of war (see Figure 4). There are precedents for this kind of reading, and it would not be the first time in twentieth-century culture that the symbolism of a medieval altarpiece came to stand for war losses. During World War I, Germany’s wounded soldiers were encouraged to identify with the bleeding body of Christ in the famous Isenheim Altarpiece (circa 1512–16) by Grünewald when it was temporarily removed from its home in Colmar, Alsace, to the Munich Pinakothek. As Anne Stieglitz has argued, “the altar’s very presence in Munich … “bore witness” to the suffering of Germany’s people.”Footnote 23 Likewise, in postwar Belgium, the Ghent altarpiece became a potent emblem not only of the country’s suffering during the war but also, more specifically, of its rise again following the Allied liberation. Certainly after World War II, the newspapers in Belgium referred routinely to the altarpiece in the shortened form of “The Lamb” or the “Mystic Lamb.” Official press photographs of Eisenhower’s visit issued by the Belgian Ministry of Information also affirm that the altarpiece was no mute decoration but, rather, a crucial actor in the heroics being staged. As the official typescript on the reverse of one photograph states, “General Eisenhower points out to his entourage one of the panels of the Mystic Lamb” (see Figure 5).Footnote 24 Two months later, at the altarpiece’s formal repatriation service in the Ghent Cathedral on 30 October 1945, special places were reserved for Allied troops still stationed in Belgium.Footnote 25

Figure 4. The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb from The Ghent Altarpiece, detail of lower half of central panel, Cathedral of Saint Bavo, Ghent, 1432 (courtesy of Lukas, Art in Flanders, VZW / Bridgeman Images).

Figure 5. Photograph of General Dwight D. Eisenhower at the reception in the Palais Royal, Brussels, 6 September 1945 (from the Van Eyck Dossier, KIK-IRPA; courtesy of INBEL).

In the years immediately after the war, the altarpiece continued to serve the internationalist agenda. The painting became a focus in the rebuilding of Belgian identity at home and abroad at a time when the country faced particular challenges regarding unity. The war had only intensified the country’s divisions between north and south – between the Dutch-speaking Flemish and the French-speaking parts of Belgium. These tensions had deep historic roots that went back to the eighteenth century when French became the official language of the ruling classes in matters of science, culture, and the law, even in Flanders. The resulting inequality of the Flemings gave rise to the Flemish Movement in the nineteenth century, whereby the art, literature, and politics of the northern cities, and their local Dutch-language dialects, were “boosted by resentment towards the central power in Brussels,” as Reine Meylaerts and Maud Gonne have put it.Footnote 26 Spats in the newspapers over the Ghent altarpiece’s care after World War II reflected these residual tensions toward the center (even though many of the authors continued to write in the French language). Meanwhile, those in Brussels promoted the work as a “national” symbol. A particular realization seems to have taken place post-1945 that “Belgium” as a unified country did not exist and that it remained as fractured as ever. Where the nation could not be brought together around language, and deep rifts remained, visual culture – especially that designated as cultural “treasure,” with all the hegemonic associations the term implied – had a role to play as a peg on which to hang an externally projected image of a unified Belgium. The altarpiece became a piece of cultural sovereignty that it was hoped everyone could get behind regardless of regional difference. The painting’s essential characteristics – it was ancient, monumental in scale, painted by the nation’s best-known artist in jewel-like color, and, above all, Christian – made it particularly suitable for its postwar elevation to cultural icon.

More precisely, one can trace how the painting became bound up with Belgium’s public relations at precisely the moment when the Socialist government in Brussels was pushing internationalism as the direction in which to go amidst continuing internal disharmony and making the most of its good relations with the United States. This was the phase in Belgium’s modern history when it embraced the idea of “Europe” by signing up along with Luxembourg and the Netherlands to the Benelux Economic Union in 1948 and to the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951, a precursor of the European Union. Belgium was also proactive in the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military alliance with North America, which was established in 1949, and joined NATO that year in support of American nuclear power. Eisenhower became the first supreme commander of NATO in 1951.

More generally, pro-American politics in Belgium were boosted after the war by the country’s marked economic recovery fostered by the continuing presence of the American military between 1944 and 1946Footnote 27 and by financial support from the Marshall Plan, which provided funds to Belgium from 1948 onwards.Footnote 28 Belgium became “a fabulous island of plenty,” as it was dubbed by one American traveller that year, who was writing for the College Art Journal. Footnote 29 Historians today still speak of the American “cult of abundance” in postwar Belgium, an increase in prosperity that was fostered by the mass importation of American products – from chewing gum and tobacco to motorcars, spirits, and soft drinks. In 1947 alone, 10 million pairs of expensive nylon panty hose were imported to Belgium from the United States.Footnote 30

Culturally, too, Belgium was making its mark on the American imagination because of the uniquely preserved atmosphere of the past that lingered in its ancient streets. In part because the country had remained under German occupation for much of the war, the medieval towns of Bruges, Ghent, and Malines remained untouched by bomb damage. Postwar Belgium promised the American tourist a magical experience, noted the College Art Journal correspondent, in a gentle satire of fifteenth-century Flemish art, “from the moment he holds his new passport in his hands with the sweet self-confidence of a saint with an attribute.”Footnote 31

If the cultural and political contexts outlined above shed light on the background to the rising profile of the Ghent altarpiece after the war, the wealth of press cuttings in the archives of KIK-IRPA in Brussels tells us just how purposefully conducted was its use as part of the Belgian international effort in that period. The endeavor culminated in the ultimate goal – the removal of the altarpiece from Ghent to Brussels for major conservation between October 1950 and November 1951. The main actor was the head of the central laboratories in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels, Paul Coremans, already mentioned, who was fast becoming a leading figure internationally in the field of museum conservation. However, the legal ownership of the altarpiece as church property, which helped to expedite its restitution in 1945, now worked against Coremans’s objective.

The altarpiece’s case posed a particular challenge because its care did not fall under the jurisdiction of a museum, and the specialist environment that this entailed, but, rather, of the cathedral chapter in Ghent.Footnote 32 Thus, Coremans’s fight to get the altarpiece the expert treatment it needed had to be political from the outset – explicitly outward facing and rooted in the language of cultural patrimony. Necessarily, it had to win over the favor of the conservative naysayers among the clergy at Ghent who opposed the removal of the altarpiece, most notably canon Gabriel Van den Gheyn (1881–1961), who was the warden of the cathedral’s treasures during both World War I and II and the archivist for the Diocese of Ghent.Footnote 33 After repeated canvassing of the authorities, however, Coremans was eventually granted 300,000 francs by the Belgian Parliament on 5 October 1950, when the chamber of representatives voted in favor of subsidizing the restoration.Footnote 34 With the reluctant agreement of the church and support from the Ministry of Public Instruction, which funded the laboratory of the Royal Museums, the altarpiece was disassembled and removed from the cathedral to Brussels on 13 October 1950.Footnote 35

Restoration

The archives of KIK-IRPA provide important insights into how Coremans’s campaign was won. A landmark on the road toward the restoration was the publication in November 1948 of a large-scale volume of high resolution photographs of the altarpiece, co-edited by Coremans and his deputy, the head of department of the archives and laboratory of the Royal Museums, Aquilin Janssens de Bisthoven (1915–99).Footnote 36 This corpus of some 200 details taken in black-and-white photographs, in extreme close up, together with an essay on the history, interpretation, and condition of the altarpiece, was a politically astute use of the best of the scientific images taken in the Brussels laboratory during the painting’s documentation in October 1945 before it was returned to Ghent.Footnote 37 With the acknowledged support of Charles Sawyer, the former American ambassador to Belgium who had acted for the painting’s restitution in 1945, and a preface by Camille Huysmans (1871–1968), the minister of education and recent prime minister (1946–47), who was successor to Achille Van Acker, the volume’s diplomatic agenda was clear.

Accordingly, the claims made for the book’s significance at a press conference on 4 November 1948, when the publisher Albert Pelckmans addressed the gathering, were overtly nationalist. As it was reported by Antwerp’s leading Liberal newspaper Le Soir, Pelckmans was keen to emphasize the important “spiritual and cultural mission” at stake in disseminating knowledge of “this important piece of Belgium’s artistic heritage” following its recovery by the Allies.Footnote 38 Going forwards, it was envisaged, the book would be an indispensable intermediary between elite and popular audiences – “from the poet or the man of science on one hand and the public on the other.”Footnote 39 Thus, a broader “imagined community” of Belgian compatriots united by art, to borrow Benedict Anderson’s well-known term for the social construction of “the nation,” was already being conceived of during this formative period in both the altarpiece’s history and Belgian identity politics.Footnote 40 All those involved in the book’s publication, concluded the report in Le Soir, were to be praised for a remarkable contribution to the domestic industry and for this new claim to fame for Belgium.Footnote 41

The book was promoted at another press conference on 24 November 1948, this time in Rome, by the Belgian ambassador André Motte.Footnote 42 The guest of honor was the Italian minister for foreign affairs, the anti-fascist Italian diplomat Count Carlo Sforza (1872–1952), who had lived out part of his wartime exile in Belgium. Sforza was another internationalist who, following his appointment as Italian foreign minister in 1947, supported Italy’s pro-European policy and the country’s joining of the Council of Europe.Footnote 43 Nor was it irrelevant that Sforza, like his colleagues in the Belgian Foreign Service, was fervently pro-American and a vociferous advocate for the Marshall Plan and NATO.Footnote 44 The occasion of the press conference was the opening of an exhibition in the Venetian Palace of the history of Belgian art and illustration through the medium of the illustrated art book, itself a genre that was growing with the improvement of photography and the rise of art documentation after World War II.Footnote 45 Center stage was given to the new Van Eyck edition. Making explicit the link between the book, the altarpiece’s wartime history, and its rise again in the aftermath, the Belgian socialist newspaper Le Peuple was quick to point out the irony of admiring this fine volume about “the famous Ghent altarpiece, returned from the salt mine in Tyrol where the Germans had taken it,” in the very building that Benito Mussolini had made his headquarters.Footnote 46 The book was described simultaneously as a “marvel” and a “monument” – unsurprisingly, the Belgian foreign correspondent for Le Peuple waxed lyrical on the opportunity to showcase the national heritage, and in Rome of all places, with its rich artistic associations.Footnote 47

The year 1948 marked a turning point in support for Coremans’s project in other ways. It says a great deal about the political sensitivity still surrounding the Ghent altarpiece that even though the authorities would not permit the removal of the Van Eyck for treatment, the restoration of another artwork returned from Altaussee – Dieric Bouts’s triptych of The Last Supper was carried out in the Brussels laboratory in 1948. The procedure, which included the development of sophisticated micro-chemical analysis of the paint surface, expanded Belgian expertise in the scientific treatment of artworks and paved the way for the restoration of the Van Eyck altarpiece.Footnote 48 It was also in 1948 that Coremans recorded during February and March of that year, as part of a permitted monitoring of the polyptych in situ at Ghent, that it showed signs of serious deterioration even since the end of the war. The varnish, he observed, was becoming dull and powdery and had lost its transparency. The paint layers were lifting and peeling.Footnote 49 This evidence can be identified as the moment of leverage that Coremans needed to exert renewed pressure on the authorities. “Let’s review the thinking in the months leading up to the painting’s arrival in Brussels on 13 October 1950,” he later wrote:

A few years ago – in September 1945, to be precise – the Mystic Lamb was back from its war wanderings. Its stay in very different physical conditions of temperature and humidity had taken their toll on the health of the paint layers and varnishes. First, we thought of an immediate response. However, the laboratory offered to wait, in the hope that the altarpiece would readapt to the atmosphere of Saint Bavo, a hope which initially seemed to materialize.Footnote 50

By 1948, however, it was Coremans’s view that the church must be persuaded to act. The care of the altarpiece could no longer be left to the church alone or, even worse, to chance. Instead, it ought to be handled by the international community:

What to do? Should one let the damage grow until its consequences became glaring for all and requiring of a response which was more serious and more risky? This was, no doubt, an easy solution but tantamount to granting the masterpiece a new and longer period of decay. Was it better, on the contrary, to declare bluntly that any delay meant a consolidation of the damage and exposing the polyptych to risks that a timely intervention could still prevent? … Public opinion, which, fortunately, is interested in the conservation of the national heritage, could hardly admit that the fate of an illustrious patient was confined to one doctor, who would refrain from consulting his colleagues!Footnote 51

Coremans had played his international card at the right moment, and it was agreed that the time had come to call in the experts. Although things did not proceed for many months, Coremans had made his point. Between 27 and 29 March 1950, the church granted him a special examination of the altarpiece, which was temporarily dismantled and placed in the Bishop’s Palace for this purpose.Footnote 52 Next, the Ministry of Public Instruction approved the restoration project based on the laboratory’s assurance that it would bring together an international commission of specialists from a variety of backgrounds to advise on the altarpiece’s conservation.Footnote 53

Thus, Coremans appealed to the specific mood of the time regarding the protection and treatment of cultural objects after the war and to the explicitly transnational thinking that produced bodies such as the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1945 and the International Council of Museums (ICOM) in 1946, with both of which he was involved. These organizations were formative in promoting the importance of cultural heritage, and not just political and economic recovery, for the moral and intellectual life of nations following the war. They also identified ethical issues and codes of conduct for museum professionals in a newly conceived of global context. After the war, the preservation of “cultural goods” – specifically, those in “international circulation” – was seen to be key,Footnote 54 and it is striking that high-ranking officials from both UNESCO and ICOM sat on the first expert committee set up by Coremans to advise on the treatment of the Ghent altarpiece.Footnote 55

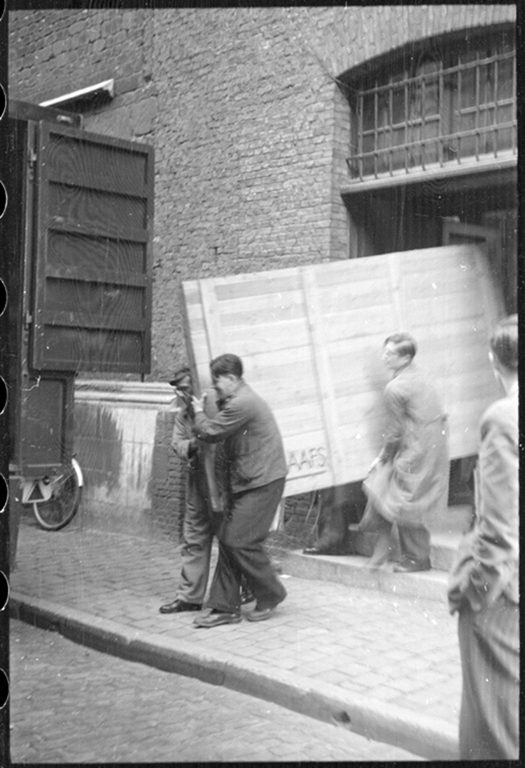

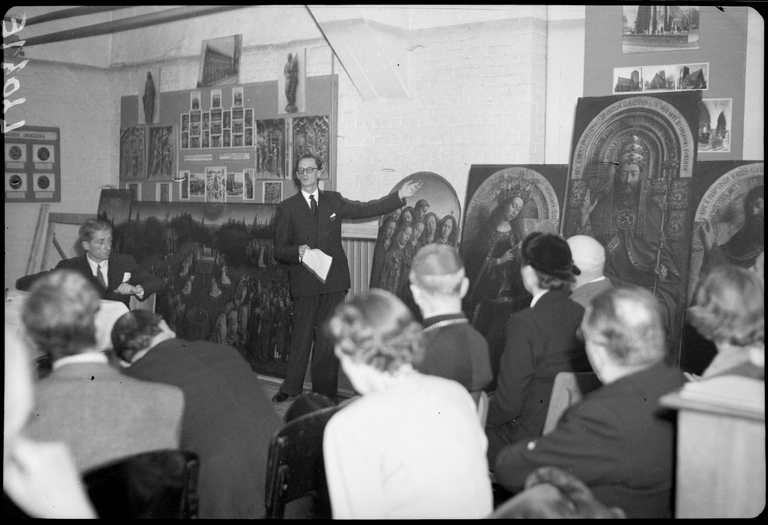

The altarpiece left the Cathedral of Saint Bavo on 13 October 1950 (see Figure 6). Following its arrival in Brussels under armed guard,Footnote 56 the first international advisory committee took place on 10 November in the laboratory of the Royal Museums, which was actually in the basement of the building. Archival photographs show the meeting taking place in front of the altarpiece panels, which were propped up against the walls and pipework (see Figure 7). If this was not remarkable enough, the caliber of the invited guests was yet more so in one sense but not in another. As it has already been noted, Coremans was held in high regard by this time in the field of conservation science, which was developing rapidly in response to the war. Numerous handwritten correspondences in the archives of KIK-IRPA demonstrate that Coremans enjoyed highly cordial international relations with peers in museums across Europe and the United States.Footnote 57 One of the most interesting of these relationships was with the commanding officer of the MFAA, George Stout, who was mentioned at the start of this article. Coremans was himself a “Monuments Man” of a kind, whom, during the war, had coordinated the documentation of art and cultural heritage all over Belgium.Footnote 58

Figure 6. Photograph of panels from The Ghent Altarpiece leaving the Cathedral of Saint Bavo, Ghent, 13 October 1950 (from the Van Eyck Dossier, KIK-IRPA; courtesy of KIK-IRPA).

Figure 7. Photograph of panels from The Ghent Altarpiece at the first international meeting of experts in the laboratory of the Royal Museums, Brussels, 10 November 1950. Paul Coremans can be seen addressing the convention (from the Van Eyck Dossier, KIK-IRPA; courtesy of KIK-IRPA).

In November 1945, Coremans visited Austria and Germany where he assisted with the repatriation of works of art at the Munich Central Collecting Point.Footnote 59 Even before this visit, Coremans was part of an international network of curators and museum directors who were active in the exchange of scientific and technical information for the protection of art objects during the war, experiences that Coremans wrote up as a short book in 1946.Footnote 60 In June 1945, Coremans was in London to learn more about the measures taken by the British Museum and the National Gallery to safeguard their collections in wartime. Although he acknowledged the help of the directors of these museums – Sir John Forsdyke (1883–1979) and Sir Kenneth Clark (1903–83) – Coremans’s real interest lay in the expertise of Harold Plenderleith (1898–1997), the head of the research laboratory of the British Museum, and Francis (F. I. G.) Rawlins (1895–1969), the scientific advisor to the Trustees of the National Gallery.Footnote 61 Like Coremans, their research training was in chemistry. Together with Stout, whose expertise also lay in the chemical treatment of art, Coremans, Plenderleith, and Rawlins were instrumental in establishing the discipline of scientific conservation that we recognize today. As the initial examinations of the Ghent altarpiece showed, the new conservation was radical because it used physico-chemical analysis to understand the raw materials of paintings and the causes and effects of deterioration and to develop material techniques to halt or repair damage.Footnote 62 This was a considerable step forwards when most museum conservation was limited to retouching and repainting, usually carried out by part-time picture restorers whose principal qualifications were more often than not as expert forgers.Footnote 63

Coremans and Stout had worked closely in a transatlantic partnership for several decades, quite aside from Stout’s mission with the MFAA. As early as 1937, Coremans visited the laboratory of the Fogg Art Museum, where Stout had been head of the department since 1933.Footnote 64 Founded in 1928, the Fogg’s research facility was the first of its kind in the United States, while the creation of Coremans’s laboratory in the Royal Museums in Brussels was not far behind it in 1934. To put these innovations in context, the conservation department of the National Gallery was not established until 1946. This development came about as the result of a controversial period of picture cleaning at the National Gallery between 1936 and 1946, which led to a government enquiry in 1947.Footnote 65 At stake in the discussions surrounding what became known as the National Gallery cleaning controversy, when 70 newly brightened “Old Masters” went on show in 1947, was the removal of discolored varnish from paintings, often referred to at the time as the “patina” of a work of art. Critics of the National Gallery, including the distinguished art historian and director of the Warburg Institute, Ernst Gombrich (1909–2001), and the head of the Istituto Centrale del Restauro in Rome, Cesare Brandi (1906–88), deplored the removal of even the uppermost varnish layers of a picture, which they considered tantamount to losing the master’s touch.Footnote 66

Sensing no doubt that those in the vanguard of the new conservation would be more sympathetic to the march of progress, the committee of enquiry sought the views of two international experts – Coremans and Stout – who reported to the historian and president of Trinity College at Oxford University, J. R. H. Weaver (1882–1965).Footnote 67 It is important to note the enquiry found that no damage to the paintings had taken place, and, despite the controversy, the gallery’s new director, Philip Hendy (1900–80), who was the successor to Sir Kenneth Clark, remained in his post. In many ways, the National Gallery was in the vanguard of conservation methods. The controversy, however, remained current and came up again frequently in the Belgian press in the lead up to the international convention on the restoration of the Ghent altarpiece.

In 1950, during the same year that the campaign for the restoration of the Ghent altarpiece was being fought, Coremans and Stout further consolidated the standing of the new conservation by founding the International Institute for the Conservation of Museum Objects (IIC), another body that remains the primary professional society for conservators internationally.Footnote 68 London was chosen for its headquarters, as a hub between Europe and the United States, and George Stout was named president. Coremans, Plenderleith, and Rawlins were fellows, and the IIC shared its premises with the trustees of the National Gallery until 1968. From the outset, the IIC’s aim was to make transparent the decisions that conservators made and the treatments they applied in knowable, scientific ways. In short, in a highly evocative turn of phrase, the IIC was founded to put an end to “the secrets of the Old Masters,” and to challenge those curators who held the line against conservators by claiming to protect the “original” work of art. The new conservation was highly skeptical about even the possibility of returning artworks to their earliest state following the march of time and pioneered methods of stabilization instead. This shift in thinking marked a crucial juncture in modern attitudes toward conservation and was one that came strongly to the fore in the treatments proposed for the Ghent altarpiece.

Indeed, the international commission for the restoration of the “Mystic Lamb” and the ensuing press coverage mirrored exactly the personnel, philosophies, and divisions between the different camps described above. Present in Brussels for the first international convention on 10 November 1950 were George Stout; Philip Hendy, the director of the National Gallery; Neil Maclaren (1909–88), supervisor of the National Gallery’s conservation department; René Huyghe (1906–97) of the Louvre; Georges Salles (1889–1966), director of the French Museums; and Arthur Van Schendel (1910–79), head of conservation at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.Footnote 69 Notably, Rome’s Cesare Brandi, the National Gallery’s strongest critic, was only invited at the last minute at the insistence of the Ministry of Public Instruction after the Italian ambassador intervened. Hendy attended the first meeting, only narrowly avoiding the cancellation of his invitation by the Ministry of Public Instruction to the second gathering on 12 January 1951 when Coremans intervened on Hendy’s behalf. The issue was Hendy’s association with the National Gallery cleaning controversy, and, to circumvent negative publicity, Hendy was replaced at the third meeting on 23 February 1951 by Harold Plenderleith.Footnote 70

No amount of advance publicity for the first meeting in November 1950 or the prestigious list of international delegates, however, could stem the public outcry over the proposed restoration of the altarpiece and the hostility with which the plans were met by the newspapers in Belgium. The arguments against Coremans’s project included the commonly expressed view that the artwork, with its long history of looting and theft – most recently, by the Nazis – had been through enough. The emotional tenor of these objections was reinforced by the articulation of specific and well-informed concerns about the further damage that could result from the restoration process itself. As we have seen, the field of scientific conservation was undergoing both an enlightened renaissance and a moment of intense opposition at this time. Frequent reference was made to the National Gallery in London and other picture cleaning controversies of the day. And, if one follows the subtext, it is also possible to discern concerns in some quarters that, if the altarpiece were to leave Ghent for Brussels, it would never be returned and would instead be given a new home in the capital at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts.

Redemption

A sample of the newspaper reports in Belgium in 1950–51 conveys a strong sense of the new controversy that was growing around the case of the Ghent altarpiece. Le Peuple, Le Soir, Grenz Echo, Het Volk, La Wallonie, Le Matin, La Nation Belge, and La Flandre libérale spoke respectively of “The Misadventures of the ‘Mystic Lamb’: A Delicate and Disturbing Experience”; “A National Problem: The Restoration of the ‘Adoration of the Mystic Lamb’”; “Disease of the ‘Mystischen Lammes’”; “A Hospital Visit to the ‘Lam Gods’”; “To Save the Mystic Lamb”; “A Thorny Question: The Restoration of the ‘Adoration of the Mystic Lamb’”; “Sickness of the Mystic Lamb”; “A Delicate Affair: Is the Mystic Lamb in Danger?” and “The Quarrel of the Mystic Lamb.”Footnote 71 An additional and recurrent theme was the near-providential nature of the altarpiece’s survival in the face of its many ordeals. This script emerged in the press in the form of an implicit redemption narrative in which the altarpiece had been saved – up to then – by miraculous means rather than by circumstance. The divine or supernatural language employed in these accounts suggests a larger popular internalization of the altarpiece’s visual content whereby the image of the “Lamb” had entered the general consciousness as a mystical symbol of its own fateful journey. Such a script also drew sharp attention to the perceived new danger posed by the controversial restoration project.

“Leaving Ghent for the fourth time!” announced De Nieuwe Gids, the Dutch-language Catholic Belgian newspaper,Footnote 72 making reference, no doubt, to the previous removals of 1794, 1816, and 1940 – the taking of the central panels to Paris during the Napoleonic wars; the sale of the wing panels to the art dealer L. J. Nieuwenhuys (1777–1862) from whom they were sold on to the German art world; and the removal of the whole polyptych to Pau in France for safekeeping during World War II before it was confiscated by the Nazis in 1942.Footnote 73 “The odyssey of the Mystic Lamb begins again,” grumbled the satirical magazine Pourquoi-pas?. Footnote 74 La Nation Belge spoke of the altarpiece’s “adventurous destiny,” likening its survival to that of a burning flame, always rising from the ashes.Footnote 75 Grenz Echo, Belgium’s only German-language daily newspaper, serving the country’s region on the eastern border with Germany (and banned during World War II for its anti-Nazism), focused on the altarpiece’s narrow escape from being blown up altogether at the close of the war when an over-zealous SS officer laid bombs in the salt mines of Altaussee.Footnote 76 These were disabled by the mine’s operatives. Le Matin thought the fresh apprehension about the altarpiece directly proportionate to the dangers it had already overcome, a history that “only added to its aura.”Footnote 77 La Métropole similarly observed that “so many dangers have perhaps made [the altarpiece] even more dear to us.”Footnote 78 The word “miracle” was commonly used – La Nation Belge declared it “a miracle that its precarious existence could have continued through so many vicissitudes”; according to the Grenz Echo, disaster in the mines was averted only “by a kind of miracle.” Le Matin thought “the miracle – because it is a miracle” was “that the Mystic Lamb is still there,” while La Métropole contemplated “by what miracle do we find [the altarpiece] still so complete today?”Footnote 79

Likewise, the word used by more than one newspaper to describe the altarpiece’s protracted movements was “pérégrinations” (wanderings)Footnote 80 a term with religious associations of the arduous journey taken by a pilgrim to a place of spiritual respite. For most people in Belgium, as even America’s Time magazine observed from a distance in 1951, the altarpiece had suffered through “500 years of wars, fires, thefts and the ministrations of countless well-meaning artist-restorers,”Footnote 81 and its safekeeping was not to be risked again by removing it from its sacred home in Ghent. The most evocative expression of the spiritual dimension to concerns about the altarpiece in the contemporary imagination came from La Nation Belge on 22 October 1950, nine days after the altarpiece had left Saint Bavo’s for Brussels. Here, the mystical link between the holy iconography of the central panel of the altarpiece itself – where groups of saints, pilgrims, martyrs, and prophets come forward in worship toward the Lamb of God – and the altarpiece’s own recent near sacrifice, was made explicit. What spell is attached to an old painting, 500 years old, the newspaper asked, so that the attention of its readers is diverted from the problems of the world to “the anxious expectation of its health bulletin?” The answer, continues the article,

is that, suddenly, the idea that [the altarpiece] might be lost makes us feel in our physical being, in our flesh and in our mind, all that it represents to us. It materializes the best of our spiritual heritage. The high flame that it projects, at more or less long intervals, has always continued to spring from the ashes that have constantly accumulated over the ages and it is always this [flame] which smoulders on the altar where the members of the sacred race come to revive their torch. Is it not an extraordinary phenomenon that so many things are tied to a wooden board or continue to dissolve, a little colour and varnish, into dust?Footnote 82

The writer of the piece was the Antwerp-born art critic Charles Bernard (1875–1961) from the northern, Flemish region of Belgium, an eminent literary figure well known for his writings on the visual arts for the Antwerp newspaper Le Matin as well as for La Nation Belge. Bernard’s was one of a number of dissenting voices on the matter of the imminent restoration treatment, which came from two groups of journalists in particular: those in the north or those who wrote for newspapers in the north (along with their fellow separatists in Wallonia in the south) and those who were artists or art critics. Chief among these names were the Ghent writer Gontran Van Severen (1905–88) in La Flandre Libérale; Richard Dupierreux (1891–1957), chief art critic of Le Soir and teacher of cultural history at the Institut supérier des Beaux-Arts in Antwerp; the Wallonian politician and writer Louis Piérard (1886–1951) in Le Peuple; and the artist Henri Kerels (1896–1956) for La Lanterne and La Meuse.

Moreover, these objections to Coremans’s project came not from a rogue group of radicals but from the very center of the arts establishment. Bernard was a leading member of the Belgian Royal Academy of French Language and Literature, to which Dupierreux was later elected in 1956. Both served as presidents of different branches of the Belgian Press Unions, while Dupierreux had been chief-of-staff to the Belgian minister of arts and sciences, Jules Destrée, during the 1920s and was closely involved in the work of the International Museums Office.Footnote 83 Van Severen was a member of the Association des Ecrivains de Belgique and the Royal Commission for Monuments and Sites.Footnote 84 Piérard was a distinguished parliamentarian, ardent socialist, and leading figure in literary society in Belgium, which led to his election, like Bernard and Dupierreux, to the academy in 1949. He was also more interested than most in the altarpiece, having published “a romance” based on the unsolved theft of the Just Judges panel in 1934, which was “part crime novel, part history of art,” as he described it.Footnote 85

The newspapers of Ghent and Antwerp were among the most vocal in their concerns about the conservation project. Behind their unease over the restoration lay another, almost unspoken fear that the work of art could be removed from Ghent for good. As several newspapers pointed out, the question of ownership remained an unsettled one. The polyptych was not quite the church property of Saint Bavo’s Cathedral in its entirety because the Adam and Eve panels had been transferred to the Belgian state in 1861 in exchange for copies of the wing panels that were then in Germany.Footnote 86 Writing in the Ghent newspaper La Flandre Libérale on 14 October 1950, Van Severen hinted at the problem, calling the issue of ownership “delicate and complex.” The Ghent people had been given a guarantee that the altarpiece would be returned to them in time for Easter 1951, he reported. His article disclosed a deeper fear, however, when he added: “There can be no question, nor can it be evaded under any pretext, that this jewel of artistic patrimony and cultural tourism is the heritage of Ghent; or of its importance to the city of Ghent.”Footnote 87 Likewise, Pourquoi-pas? noted that the chapter of Saint Bavo was known for its “extreme sensitivity … for all that concerns the famous painting, and which is explained all the better because the question of co-ownership is still pending, between the State and Ghent, of certain parts [of the altarpiece].”Footnote 88 Piérard, in Le Peuple, urged the state to have a say regarding the impending treatment,Footnote 89 while Dupierreux, in Le Soir for 18 October 1950, acknowledged that even before the war there had been concerns about “the questionable conditions of conservation” at Saint Bavo’s Cathedral among museum curators, who felt that the work should be in the care of specialists in one of Belgium’s state galleries.Footnote 90

Dupierreux’s comment was accurate – one such opinion can be found in print by Thomas Bodkin, former director of the National Gallery of Ireland and founding keeper of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham. In his wartime report on internationally displaced works of art, Bodkin had written pointedly of the unsuitable atmospheric conditions to which the altarpiece was exposed in Ghent, citing a lack of adequate heating, lighting, and security in the church setting:

The city of Ghent can scarcely be said to have deserved … the van Eyck altarpiece … The ecclesiastical authorities had not proved themselves worthy custodians of this treasure in the past. … Though in most cases it is eminently desirable that monumental pictures should hang in their original site, the van Eyck altar-piece, if it survives the war, might be made an exception to the rule. Were it sent to the Royal Museum at Brussels it could be displayed to much greater advantage, be better preserved and looked after, and be seen by far more people than at Ghent.Footnote 91

Concerns raised by such views rumbled on in the north throughout the duration of the conservation project. In December 1950, the Antwerp newspaper La Métropole printed an apparently reassuring comment from the chief curator of the Royal Museums in Brussels, Paul Fierens (1895–1957), whereby he was quoted as saying: “The people of the north hold the altarpiece at Ghent as the Bible and four gospels of their artistic life.”Footnote 92 The paper was quick to downplay his remark, however, as a hollow understatement of the “extraordinary aura of this celebrated work, which is, in reality, one of the most important artistic reference points of the culture of the whole world.” The altarpiece was a “universal treasure,” the newspaper argued, and although beauty lovers of all kinds were interested in it “as if it was their kin,” it was “Ghent’s treasure.”Footnote 93 In February 1951 when the Easter deadline for the altarpiece’s return was looming, the same newspaper printed an interview with Gabriel Van den Gheyn – the aged Ghent cleric who had kept the altarpiece safe during World War I – in which he too referenced the anxieties about the artwork staying in the capital. Despite the desire expressed in certain quarters of the press for the work to remain in Brussels, he cautioned, the altarpiece “is and remains the artistic heritage of the Ghent people.”Footnote 94

Those in the north were equally skeptical when it came to the question of the restoration itself in the run up to the meeting of experts in Brussels on 10 November 1950. In Antwerp, Paul Vaucaire in Le Matin observed on 28 October how the case of the Ghent altarpiece had reignited animosity between the public and picture restorers. The “problem is thorny, and we cannot be careful enough,” he professed in the case of the “Van Eyck,” urging caution, hesitation, even, on the part of Coremans’s team. “Is the cleaning really essential?,” asked Vaucaire, and “to what extent should it be carried out?”Footnote 95 On the day of the first international commission, Le Matin launched a more pressing alert. Concerned by the number of international scandals caused by “over-cleaning” paintings in recent years, and by the unpredictability of how the physical make-up of the Van Eyck altarpiece might itself react to such a treatment, now Yves Bourdon sounded a warning:

The alarm call is given. If [a newspaper article] makes less noise than exploding bombs or other such incendiary sounds [no doubt referencing the bombs laid in Altaussee in 1945], too bad, but we must not remain indifferent. The Mystic Lamb is a universally recognized masterpiece. It constitutes a capital piece of our artistic patrimony; its conservation directly concerns us.… We are not indifferent that this afternoon the experts are gathering in Brussels to take a decision.… We must do what we can to preserve a work of art in danger. But not by threatening it with another danger!Footnote 96

Since the bulk of these editorials came from prominent figures in the arts who were well versed in the postwar debates around conservation, the newspapers were also able to identify quite precisely the nature of the “danger” they feared in relation to the Van Eyck. Coremans’s plan was threefold – to inject a soft wax into the rear supports of the panels to increase the wood’s flexibility and ability to adapt to variations in temperature and humidity; to stabilize the deteriorating paint layers by the application of a composition of wax and resin to the surface of the panels; and to remove the old varnish that covered the paint layers, especially where it was lifting and threatening the oil paint beneath. It was also proposed that areas of later over-painting would be removed.Footnote 97

The majority of the debate focused on these last propositions – the ones involving physical removal – because it was this kind of “picture cleaning,” necessarily involving the use of solvents, that had caused such outcry with regard to the National Gallery’s cleaning controversy in London. There, the issue had been the re-introduction to the public of familiar faces – Diego Velasquez’s Portrait of Philip IV of Spain (circa 1656) or Peter Paul Rubens’s Portrait of Susanna Lunden (1622–25) – sporting much brighter hues than previously, without the top layer of historic, discolored varnish to mellow their intensity. In Belgium, news of the proposed restoration sparked fears that the altarpiece would be similarly and irreversibly altered.

Writing for La Lanterne Brussels on 16 October, three days after the polyptych’s arrival in Brussels, the artist Henri Kerels was among the first to get specific about the risks associated with the scientific removal of varnish in old paintings. Velasquez’s Portrait of Philip IV of Spain in London had become “a nothing work, after scraping,” he wrote, while, closer to home, the very restorer to whom it seemed the altarpiece would be entrusted, Jef Van der Veken, had already incited controversy in the 1930s by removing a skin lesion from the face of the cleric in Van Eyck’s The Virgin and Child with Canon Joris Van der Paele in the Groeninge Museum at Bruges.Footnote 98 In the case of the Ghent altarpiece, where the line between the brilliant oil colors of the painting and their suspension in other mediums was as yet undetermined, commentators like Kerels feared that, once the process was begun, the work would “eventually undergo such a transformation that it will end up little more than a ghost.”Footnote 99 Similarly, Louis Piérard in Le Peuple likened the stripping back of Rubens’s Susanna Lunden at the National Gallery to an “assassination,”Footnote 100 while in Le Soir on 18 October 1950, Richard Dupierreux questioned the right of scientists to assume authority in the treatment of ancient works of art.Footnote 101

No doubt in response to these protests, Coremans organized two press conferences – on 19 and 26 October 1950 – in which he offered access to the journalists, addressing them directly in the laboratory.Footnote 102 These events prompted more fears than they allayed, however, provoking complete astonishment, on the part of Henri Kerels, writing for La Meuse on 31 October 1950, that Coremans’s team had already gone ahead with treatment upon one panel – the Holy Hermits – without waiting for the approval of the international panel of experts. Surely, the application of wax to the wood – a substance Kerels thought would never dry – was a fire hazard, he added, musing on the near loss of the altarpiece to the fire caused by a falling cinder in 1822 that landed on the painting in the cathedral at Ghent.Footnote 103 Richard Dupierreux’s pieces for Le Soir also became more hostile, culminating in an impassioned plea on 20 October 1950 for museum keepers and curators, not the men of science, to have the final say in matters of conservation. Referring to the larger fight between international gallery professionals over conservation being played out in UNESCO’s journal Museum International the same year, Dupierreux urged that the school of “totalitarian” restorers, intent on removing whole layers of varnish, be stopped. Where the varnishes are removed like so, he wrote, “one flinches from the physical assault, as if the painting were flesh, skinned alive.”Footnote 104

Thus, metaphors of illness and the body were another common leitmotif in the newspaper coverage of the Ghent altarpiece’s conservation treatment. On 20 October 1950, Pourquoi-pas? quipped that the altarpiece panels were to undergo “a facelift, by the clever hand of Mr. Van der Veecken [sic], the Voronoff of the old canvasses.”Footnote 105 Since Serge Voronoff (1866–1951) was a widely discredited doctor of skin grafting active during the 1920s, this comparison played upon the fact that now Van der Veken’s reputation was on the line. As we have seen, his heavy-handed cleaning of Van Eyck’s The Virgin and Child with Canon Joris Van der Paele – with its removal of Van Eyck’s rigorously painted skin defect on the canon’s face – was being dredged up again by the sharp-eyed press. Shortly after the first international meeting of experts at Brussels, Van der Veken was removed from the project.Footnote 106 On 20 October, Het Volk wished the “‘sick’ Lamb of God a prosperous treatment” in the hands of its “surgeons,”Footnote 107 while, on 4 November, a double-page spread by Charles Bernard for La Nation Belge was savage on the matter of contemporary cleaning controversies. “Too many unfortunate experiences have been made and disasters caused … when doctors are called to the bedsides of [pictures],” he wrote. The new school of totalitarian restorers, with their mission to scour back to the “original” colors beneath the varnish was more likely to “remove all blood flow from their skin, reducing them to a cadaverous pallor.”Footnote 108 This was the context in which Bernard even sought the opinion of a medical doctor, printing a lengthy interview with Jules Desneux (1885–1962), a dermatologist and part-time writer on questions of art and science who urged the same caution in treating the epidermis of the Ghent altarpiece as one would exercise in the treatment of human skin.Footnote 109

This anthropomorphism of the painting as a living entity ran counter to the opposite image – to the unfeeling sterility of science and the laboratory perceived by the art press. Indebted to another expert opinion in print appearing in the journal Flambeau, Richard Dupierreux quoted the words of the distinguished Belgian art historian Suzanne Sulzberger (1903–90) who had commented on the debate. Sulzberger wrote that “the machine cannot register beauty or rarity” in a work of art nor “prestige and the crowning glory of age”; in other words, the delicacy of the patina.Footnote 110 Charles Bernard, in La Nation Belge on 4 November 1950, once again stressed the limits of a scientific approach, writing that it may never quite be known how Van Eyck laid down his colors in relation to his varnishes: “[N]o wonderful devices, measurers of wavelength, will tell us, for example, in what vehicle Jean Van Eyck crushed his colours.”Footnote 111 Here, the journalists had hit upon the crux of the problem that would be debated at length at the meeting of the international commission on 10 November. How was the laboratory to know exactly where the varnish ended and the painting proper began since it was likely that the painted surface of the altarpiece panels was not topped by one simple coat of varnish but, rather, a number of delicate glazes in which the Van Eycks had suspended luminous films of oil-painted color. By all means remove the old “‘gallery tone’,” declared the Grenz Echo on 18 October 1950, but do not let the restorers “take the picture from the picture!”Footnote 112

The main personalities called to the international commission were well known to the press in Belgium. The contrast between the cautious approach of Cesare Brandi in Rome and René Huyghe at the Louvre and that of Stout and Coremans – because they had publicly supported the National Gallery in its more radical “total” cleaning – was repeatedly drawn. Certainly, the press exerted no small influence in the decisions made to quietly remove the restorer Van der Veken and the National Gallery’s Philip Hendy from the expert panel and to ensure that Brandi, who was associated publicly with the criticism of the National Gallery, was invited to take part. Both Brandi and Huyghe had contributed in January 1950 to UNESCO’s special issue of Museum International that aimed to address the growing crisis dividing the international community of conservators. In one article, Huyghe described how “[t]he ‘total’ cleaners, strong in their faith in their own thesis, use quick radical methods, designed to remove all the varnishes relentlessly.” This method, he argued, did not allow for the stopping of the treatment in stages where the picture’s safety required it and “may even alter or ruin it or what remains of it.”Footnote 113

Since journalists in Belgium were familiar with these articles – cited as we have already seen by Richard Dupierreux in Le Soir Footnote 114 – Coremans was careful, in opening the international meeting, whose minutes are preserved in the archives of KIK-IRPA, to both acknowledge the heated debate and to call for a balanced discussion from a number of perspectives, with the politics of conservation set aside.Footnote 115 A similar sentiment had already been expressed in the foreword to the Museum International volume by Theodore Rousseau (1912–73), a former Monuments Man and curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Ten months before the restoration of the Ghent altarpiece, Rousseau had outlined UNESCO’s hopes of obtaining a statement of agreement among specialists in the face of what he called “the most vital problem for the museum profession.” His recommendation is worth quoting in full:

Yet there is no more vital problem for the museum profession. The safety, in fact, the continued existence of the masterpieces entrusted to it is at stake. … It is therefore necessary and urgent that this problem be fully examined and that all its elements be analyzed with extreme care. The experts must come forward to define their beliefs, explain the points on which they agree and those on which they disagree, in short make a fundamental statement of the knowledge which is available.Footnote 116

It could be argued that the international commission on the Ghent altarpiece offered just that opportunity. Where other restorations in Paris and Rome passed by unnoticed in all but the most specialist of journals (the National Gallery cleaning controversy not withstanding), the symbolic load placed on the Ghent altarpiece in Belgium after the war meant that it was brought front and center into public debate. A comparably high-profile symposium was needed to reach a workable agreement for the treatment program. As Coremans was all too aware, the altarpiece’s case was unprecedented, not only because of the object’s great age and size but also because, as he announced in his address to the delegates, the project would effectively have to deal with what he saw as 19 individual paintings rather than a harmonious whole.Footnote 117

Although it is beyond the scope of this article to deal in depth with the hearing of the international commission and the four succeeding meetings that took place up to October 1951, it is worth summarizing the discussions that took place and the agreements that were made in the first meeting, with reference to the main themes of the controversy that emerged in the last months of 1950. Evidently, the newspapers had exerted a genuine influence upon what followed on 10 November. Indeed, 46 pages of minutes tell a story of next steps, rather than of going over old ground, with much that was controversial having been aired already in the press. Instead, the ensemble engaged in a frank, but patient, exchange in which questions about the wax impregnation of the panels; about damp and humidity; and, above all, about how far to go in the removal of old varnishes were fully explored. Far from developing further divisions within the field, the chance to put questions to Coremans, who answered each one with knowledge and candor, seems to have united the formerly disparate group of experts. This was a test case in action for the principles of international cooperation advocated by UNESCO.

The most pressing issues were necessarily those of chemical science, the field that was shared by Coremans and most of the gathering. Absent were the well-worn divisions over whether or not to treat pictures at all, and business turned crisply to specific questions posed by the altarpiece’s case. What if the panels contained salt after their wartime stay in the salt mines of Altaussee, asked Baron P. Descamps (1884–1965), who was president of the Consultative Commission for Historic Art of the Royal Museums of Fine Art in Brussels. Would the paintings behave differently over time? To which Coremans was able to confirm that 50 separate samples taken from the panels showed that no trace of sodium chloride had penetrated them. And the new wax layers, pressed Descamps? Surely, these would lock any moisture and humidity into the wood, much like “letting a wolf loose in the sheep pen?” Should the wood not be allowed to breathe?Footnote 118 The existing varnish was more of a barrier than wax, rejoined Coremans, since wax was a neutral material that also remained stable as well as flexible.

And what about the varnish layers, insisted Oscar Joliet (1878–1969), the church representative from the Cathedral of Saint Bavo? Varnish would only be removed where it threatened the original paint layers beneath, relayed Coremans. Even repaints from the sixteenth century would not be touched, it was confirmed, and the group agreed that an old but well done restoration was better than a new one that would have to be adapted to the whole “from scratch.” Stout was vocal on exactly this point. How would the color harmony of the complete altarpiece be preserved if each part was tackled, as it must be, separately? Here, Coremans was perhaps the most candid of all. It was not possible to predict what would be uncovered until the project was underway, he returned, which was why it was important to receive the agreement of the church and the state to work without restrictions on the nature of the treatment to be given. The kinds of horror stories deplored by Cesare Brandi and René Huyghe, Coremans affirmed, concerned what was fast becoming a “historic” and totalizing way of working. He would not risk a disaster. Most significantly of all, when asked for his view, Huyghe, usually of the opposite faction to Coremans, responded that the Belgian chemist knew exactly what he was doing and exactly where each potential problem lay. Thus, quietly and peaceably, two schools were brought together around one iconic work of art. The middle way in conservation – the “do-no-harm” school of thought that has become standard – had found an early and powerful expression in Belgium during a decisive moment in the reaffirmation of its cultural identity.

Yet the shared custodianship of the altarpiece between the north and south while it was in Brussels remained an uneasy one. Once started, the conservation project prompted new areas of concern, chief of which was the (more than anticipated) highly varied extent to which different panels required removal of old varnish and overpaint.Footnote 119 The balancing act needed to preserve the coherence of the altarpiece as a whole – both regarding an even color tonality and the preservation of essential detail where the relationship between the original painting and later retouching was not straightforward – was delicate and time-consuming. An extension to the cathedral’s deadline of Easter 1951 had to be agreed upon, and the altarpiece was not returned until 19 November of that year. Its health and brighter appearance, however, was regarded by all parties as much improved. This followed the treatment of the most urgently discoloured, darkened or damaged areas, especially in the opened view of the polyptych where the team had concentrated their efforts. Above the Lamb in the central panel, the dove of the Holy Spirit now descended in a golden blaze of light after its glowing semi-circular nimbus was uncovered beneath an old layer of over-painting Dubois Reference Streeton2018, 764. In a neatly discernable way, although few may have thought about it in such terms, the renewed symbolism of the dove, with its message of hope and more usual association with the baptism of Christ, mirrored the reblessing of the altarpiece as it emerged from its latest challenge. For Coremans and his team, the restoration, carried out during such a relatively short timescale, amounted to little more than the application of a band-aid. Yet despite the concerns of the press, the project not only improved the condition of the much-loved artwork, but set a landmark in the understanding of what the critics feared would never be understood - the chemical properties of the Van Eyck medium. Knowing well that their time with the altarpiece was strictly limited, Coremans and the laboratory presciently took more than 230 paint cross-sections for subsequent analysis, from which they were able to isolate individual chemical elements in the Van Eycks’s many-layered painting technique.Footnote 120 The research yielded the watershed study, L’Agneau mystique au Laboratoire, published by Coremans in 1953, a definitive volume that was still a major point of reference for the recent conservation of the altarpiece in 2012–2018.Footnote 121 Such questions, it was proved after all, could be answered by science.

Conclusion

Involving an international community of voices and opinion, the Van Eyck restoration project offers a contemporary insight into the detail and complexities of picture cleaning and conservation in the aftermath of World War II. The particular case of the Ghent altarpiece not only tapped into and provided a new focus for long-standing divisions between north and south in Belgium but also provided a forum, especially through the international meeting of experts in November 1950, for the working out of a much larger fight between two schools of conservation in the postwar context. In the newspapers – for a generation of public intellectuals in Belgium, many of whom had lived through two world wars – the familiar face of the altarpiece, as a symbol of restored Flemish stability and postwar healing, was not to be gambled upon by modern science. Forced to work together, however, through a collaboration fostered by Coremans’s own outward-facing embrace of internationalism, the leading museum professionals of the day moved a step closer to a shared agreement on non-interventionist custodianship. Preservation had become the order of the day rather than an old-fashioned restoration.

Acknowledgments

My sincere thanks are due to Julie Mauro in the documentation department of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage at Brussels (KIK–IRPA); to Harry Bennett, Bianca Gaudenzi, and Les Parsons for their invaluable help and advice in the completion of this article; and to my father, Ian Graham, with whom many small conversations amounted to a significant whole.