Introduction

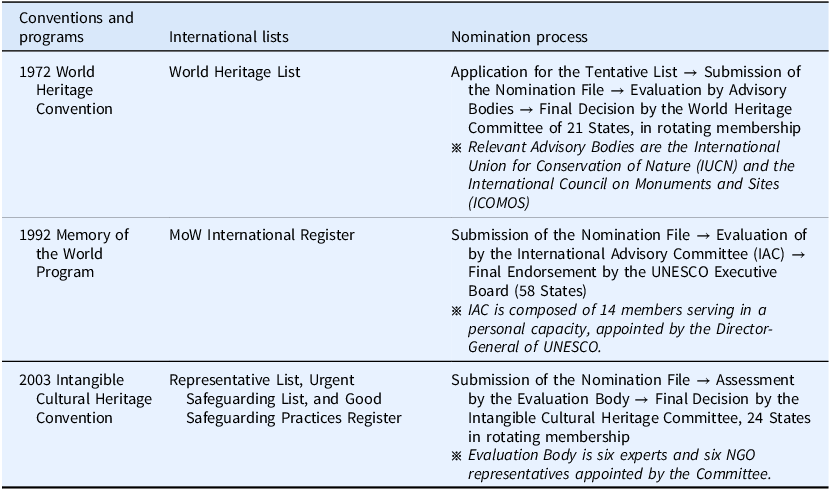

Established in 1945, UNESCO is an agency of the United Nations with a constitutional mandate to build peace through cooperation in the fields of education, science, culture, and communication. As the only UN agency dealing with cultural issues, UNESCO has, from its inception, focused on protecting cultural heritage. To this end, it has introduced several important conventions and programs. These established prestigious lists are managed by UNESCO (Table 1). Two of the best known are the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage adopted in 1972 (World Heritage Convention) and the Memory of the World Program started in 1992 (MoW).

Table 1. The UNESCO Heritage lists and their current nomination process

For many countries, inscription on these lists constitutes international recognition of their nation’s heritage. Unsurprisingly, the competition for inscription has become fierce, and the decision-making process for inscription is politicized.Footnote 1 When heritage nominations put forward by State Parties are associated with sensitive and disputed memories of history, they can produce fierce conflict, with at least one case of an actual firefight.Footnote 2 Although no bullets have been fired in East Asia, it is certainly the case that dissonant memories of imperialism, colonial rule and the wartime past remain major sources of social and political conflict among the Republic of Korea (hereafter, South Korea), Japan, and the People’s Republic of China (hereafter, China). Beginning in the mid-2010s, several memory struggles unfolded in the processes of heritage nomination: the 2015 nomination of Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution (hereinafter “Meiji Industrial Sites”, or “Sites”) to the World Heritage List; the 2015 nomination of Documents of Nanjing Massacre to the MoW Register; the 2017 nomination of Documents about Comfort Women to the MoW Register; and the 2024 nomination of Japan’s Sado Gold Mines to the World Heritage List. At present, only the Documents of Nanjing Massacre appear to be settled in official fora. Bilateral and multilateral negotiations concerning the other nominations are still ongoing.

Many scholars have written about these conflicts from the perspective of memory politics,Footnote 3 focusing for the most part on bilateral inter-state relations,Footnote 4 or in some cases looking at domestic politics to explain the stances of particular states.Footnote 5 However, many non-State actors have played roles in these heritage decision-making processes,Footnote 6 ranging from experts and NGOs to UNESCO Secretariats. In addition, perhaps because the World Heritage List and the MoW Register follow different procedures involving different actors, few studies have considered both lists together,Footnote 7 even though they are related in both bilateral and multilateral politics in East Asia and at UNESCO. This paper examines issues of both heritage systems concurrently and will consider the role of non-State actors.

This examination is also timely due to a significant shift in South Korea-Japan relations since conservative president, Yoon Suk Yeol, replaced his liberal predecessor in early 2022. Prioritizing harmonious relations with Japan, President Yoon pursued a “grand bargain” to reduce tensions in economic and security relations as well as historical understanding,Footnote 8 and in the spring 2023 the two governments announced a major political agreementFootnote 9 that changed the environment surrounding contested UNESCO heritage nominations. The impact of this very recent rapprochement has not been studied, and such hard power issues must be considered when analyzing the politics of UNESCO heritage inscriptions.

This paper offers a holistic picture of the tense politics of UNESCO heritage since mid-2010 among Japan, South Korea, and China. We look at both negotiations leading up to inscription and the aftermath of assessments and recriminations involving both states and non-state actors in a changing political, economic, and security environment, in particular between South Korea and Japan. We conclude with a look at future prospects and possible steps toward more constructive dialogue to achieve the peace building and educational goals of UNESCO’s heritage projects.

We have examined UNESCO legal and policy papers, academic publications, promotional materials from interested parties, and media accounts. One of the authors (Kim) also draws on more than 17 years of personal observations while attending official UNESCO meetings such as World Heritage Committee and Executive Board. Both authors interviewed government and UNESCO officials in Korea and/or Japan, and both visited relevant sites in Japan and interviewed key actors from various organizations.

Conflict over world heritage nomination

Japanese nomination for the Meiji Industrial Heritage Sites

In January 2014, Japan submitted the nomination dossier of the Sites of the Meiji Industrial Revolution for consideration at the summer 2015 session of the World Heritage Committee in Germany. This was a “serial nomination” of a cluster of 23 sites of mining, shipbuilding, and steel manufacturing in the 19th and early 20th century, mainly in Kyushu. Since 2006 this nomination had been strongly supported by key members of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), while the Ministry of Education’s Cultural Agency, which typically managed heritage policy, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, were less enthusiastic. Reflecting this political context, the Cabinet Secretariat eventually, and quite unusually, came to manage the nomination.Footnote 10 In 2014 the Japanese government put this nomination at the head of the line for presentation to UNESCO, leapfrogging the churches of the so-called “hidden Christians” in Nagasaki, which the Cultural Agency had set as the top priority the previous year.Footnote 11 The driving force in these efforts was Kato Koko, a passionate advocate for preserving and recognizing Japan’s industrial heritage. Kato also boasted powerful political connections: her late father had been one of the LDP’s leading politicians, very close to Abe Shintaro, the father of the late-Prime Minster Abe Shinzo, in office at the time.Footnote 12 Bolstered by strong national political ties, Kato won local support in the relevant cities and from foreign heritage experts who joined an Expert Committee to prepare the nomination.Footnote 13

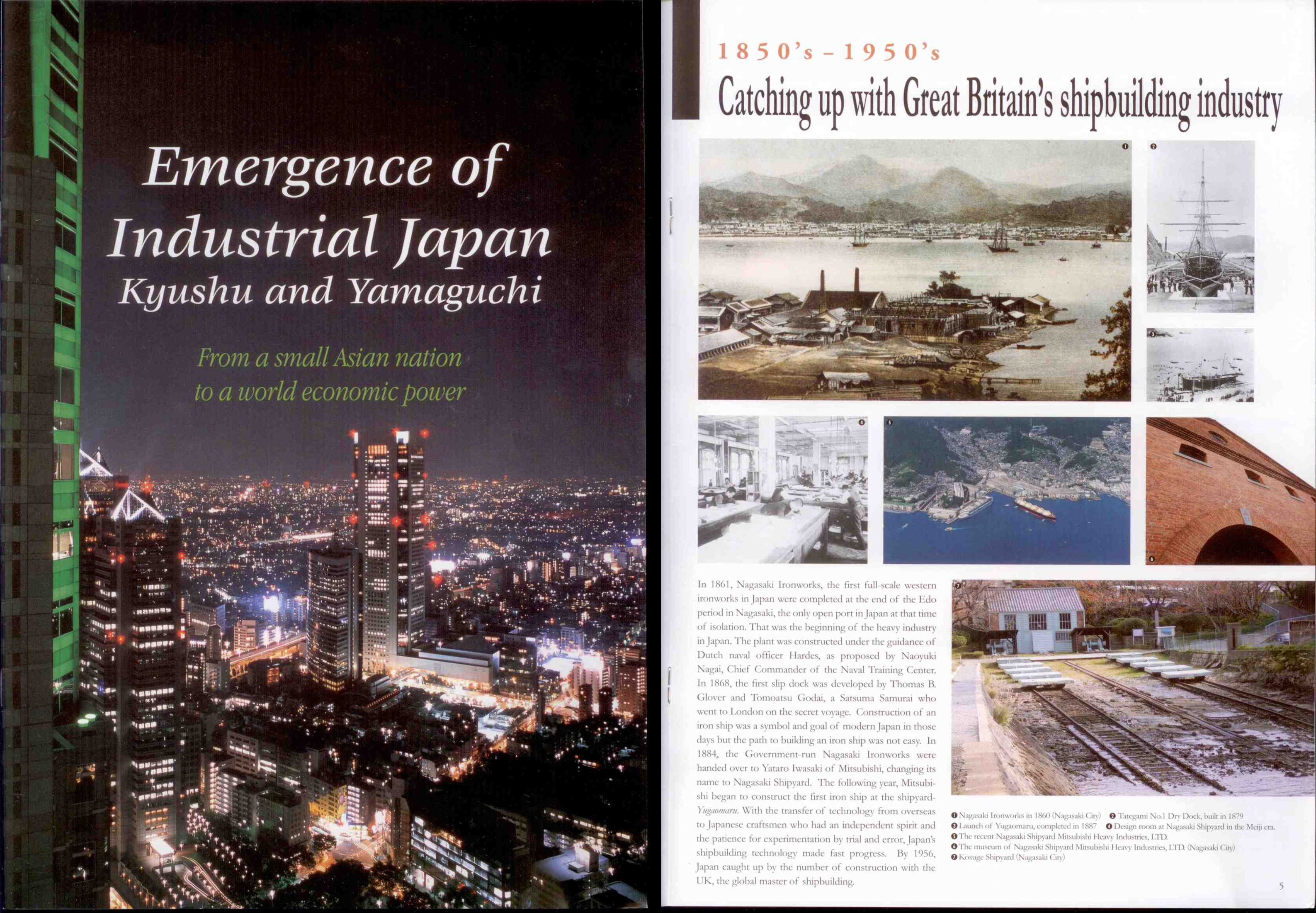

In some of the government’s promotional materials, the nomination covered a full century, from the 1850s to 1950s (Fig. 1). And indeed, these were sites of industrial production of great importance throughout this entire span, and beyond. However, the Japanese government, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA), and all supporters including Kato were well aware that some of the nominated sites employed the conscripted or forced labor of tens of thousands of Koreans, Chinese, and Allied POWs during WWII. A nomination covering the entire century would be expected to discuss the exploitation of these workers, some of whom (the workers from Korea), the Japanese government viewed as mobilized by legitimate means. In part to tell a story with a clean narrative arc focused on technological flows and adaptations in the early decades of Japan’s modernization, but also clearly to avoid the need to address wartime history, the Japanese promoters eventually decided to limit the time span of relevant industrial heritage to the decades from the 1850s to 1910, the year of the Japanese annexation of the Korean peninsula as a colony.Footnote 14

Figure 1. Brochure cover (left) and contents (right, p. 5) disseminated at the 2012 session of the World Heritage Committee (Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation) shows the time scope of the nominated sites to be 1850s to 1950.

Upon receipt of the nomination dossier, ICOMOS, the relevant advisory body under the World Heritage Convention, conducted its standard evaluation. In March 2015 it recommended the Sites for inscription, based on criteria (ii) and (iv) on the list of needed elements for World Heritage Sites. Criterion (ii) required a nominated site to “exhibit an important interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology.” Criterion (iv) required a site “to be an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble…which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history.”Footnote 15 The recommendation was made public in May 2015.Footnote 16

Backlash and negotiations

From the moment Japan submitted its nomination dossier in 2014, other countries, especially South Korea, began to fiercely criticize it. Not only the government but also a South Korean NGO, the Center for Historical Truth and Justice, mobilized opposition in cooperation with other international NGOs, including a Japanese civil society Network to Investigate the Truth of Forced Mobilization which had worked with the Center for decadesFootnote 17 and a Dutch NGO, the Foundation of Japanese Honorary Debts, which wrote to UNESCO and World Heritage Committee (WHC) member states describing the abuse of Allied POW forced laborers at some of the nominated Sites.Footnote 18 Some American politicians also raised objections. Six members of Congress, led by Michael Honda, wrote to the Chair of the WHC calling attention to the omitted history of POW abuse.Footnote 19 Mindy Kotler, a director of an American think tank, Asia Policy Point, seeking recognition and compensation for American POWS contributed an article to The Diplomat lamenting Japan’s omission of this history.Footnote 20

In this context of civil society and media pressure, in the run-up to the summer 2015 WHC meeting the South Korean and Japanese governments separately and vigorously lobbied the UNESCO Secretariat and the other 19 member states in numerous bilateral meetings. The two sides also met face to face in meetings sometimes moderated by the German chair of the impending Committee meeting and the Director of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre. The South Korean government continued to insist that the Japanese nomination should recognize that forced labor took place at some of the Sites, and the Japanese side continued to refuse. Unusually, negotiations continued even during the July 2015 WHC meeting itself. With mediation by Maria Boemer, that year’s WHC chairperson, the two sides finally reached an agreement just before the issue was to come to the floor, with the Japanese moving some distance toward the South Korean position.Footnote 21 The Japanese Ambassador to UNESCO, Kuni Sato, told the Committee that “Japan is prepared to take measures that allow an understanding that there were a large number of Koreans and others who were brought against their will and forced to work under harsh conditions in the 1940s at some of the sites.” The WHC requested that Japan prepare an interpretive strategy for the presentation of the sites to allow an understanding of their full history, and Japan promised to take follow-up actions including measures to honor the memory of the victims.Footnote 22 Believing Japan would follow through on its new commitments, South Korea agreed to support the inscription of these sites. Unlike Japan and South Korea China was not one of the 21 WHC member states at the time, so it had no vote at the meeting. However, China was present as an observer and criticized the nomination by distributing a letter of objection.Footnote 23

This agreement was significant for being reached in July 2015, because August 15 marked the 70th anniversary of Japan’s surrender to end World War II in Asia. Citizens, scholars, and media around the world – especially in East Asia – focused much attention on the sort of statement the Japanese government might issue and the degree to which it might constitute an apology or not. In this context, the agreement suggested a measure of accord on disputed historical understanding might be possible. Also significant was that Japan made some compromises despite its strong influence on the World Heritage Committee due to its huge financial contribution.Footnote 24

How was this compromise reached? One factor was a shift in the delicate balance among Japan’s domestic policy elites. A second was the mediation of UNESCO leadership, reinforced by pressures from international civil society. First, on the Japanese negotiating team, tension between the Cabinet Secretariat and MoFA continued throughout the nomination process.Footnote 25 Although not a government official, Kato Koko played a key role in the Cabinet secretariat, criticizing what she called South Korean “propaganda”Footnote 26 and opposing any compromise. Concerned about the bilateral relationship with its neighboring country, MoFA was more willing to compromise.Footnote 27 In the end, the MoFA position won the day within the Japanese delegation.Footnote 28 Second, not only Maria Boemer, chair of the WHC meeting and a Minister of State in the German Foreign Office but also Kishore Rao, the Director of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, actively mediated, in part by forwarding to the Japanese delegation the many appeals they received from around the world.Footnote 29 Decisions of the WHC are conventionally made by unanimous agreement. These external appeals and petitions made clear that a global audience was watching to see how the Japanese side would deal with this contentious nomination. In addition, Boemer reportedly referred to the fact that German industrial heritage sites inscribed on the World Heritage List such as Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex and Völklingen Ironworks presented information on victims of WWII forced labor.Footnote 30 As meeting chair, until the last moment, Boemer actively mediated the tense conflict between Japan and South Korea. In her summary comments, she expressed gratitude to both parties. She called the decision an “outstanding victory for diplomacy” that “demonstrated the strength and spirit of the Convention to bring people back together.”Footnote 31

Continuous confrontation and recent change

Unfortunately, before the ink was dry on the inscription, the Japanese side started to argue that Sato’s statement did not constitute recognition of “forced labor.”Footnote 32 The official and binding English version of the agreement used the phrased “were forced to work.”Footnote 33 The Japanese version translated this as “hatarakasareta (働かされた). The Japanese delegation had insisted on this phrase rather than the stronger term “forced labor,” which carried a meaning in international law that could support ongoing lawsuits demanding compensation to Korean wartime laborers or their survivors.Footnote 34 The Japanese negotiators probably hoped as well that this softer expression would arouse less domestic opposition from those who denied the wartime system used Korean “forced labor.” But even with the agreed upon wording, Japan clearly had a duty to comply with the WHC request that its new interpretation strategy allow an understanding of the context in which people “were forced to work.”

After the meeting, the Japanese government established a section within the Cabinet Secretariat to prepare the interpretation of the newly inscribed sites and appointed Kato as a special advisor to the Abe Cabinet in charge of this project. From this perch, she shaped the follow-up process in accord with her political vision.Footnote 35 The Japanese team made no public statements about its actions to address the history of forced labor at these sites until its State of Conservation report submitted to UNESCO at the end of November 2017 (revised in January 2018). That report used the term “industrial workers” and referred to a wartime “policy of requisition” of labor, but made no reference at all to laborers being “forced to work against their will.”Footnote 36 This was a clear retreat from the commitments made in July 2015. At its annual meeting in 2018, the WHC recognized this in its cautiously worded but nonetheless clearly displeased response to Japan’s report. It “strongly encouraged” Japan to make further efforts to establish a proper interpretation strategy following best international practices and encouraged continuing dialogue among the concerned parties. In the world of UNESCO statements, “strongly encourage” is unusually strong wording.Footnote 37

Then, in 2021, prompted by strong protests from South Korea at the lack of Japanese follow-through on its 2015 commitments, a team from UNESCO and ICOMOS inspected the newly opened Industrial Heritage Information Center in Tokyo. The mission of the Center was to put in place the basic interpretative framework for the Meiji Industrial Revolution World Heritage Sites, including discussion of wartime “labor that was forced.” The UNESCO-ICOMOS mission produced a report that, again by UNESCO standards, was unusually critical of the failure of the Japanese side to tell the full story of wartime labor. The WHC accepted the report and issued its own blunt statement, noting that it “strongly regrets” Japan’s interpretation and urging the government to honor its 2015 promises.Footnote 38

This stalemate reflected the continuing confrontation between Japan and South Korea over history issues. In December of 2015, less than six full months after the compromise reached at the WHC meeting, the leaders of the two countries had tried to boldly deal with one of the most vexing of these issues the “Comfort Women” Agreement.Footnote 39 But the agreement backfired. It was reached by Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and President Park Geun-hye in large part due to security concerns of the United States. The closed negotiations and lack of significant new support for victims inflamed public opinion in Korea, thus aggravating rather than smoothing the bilateral relationship.Footnote 40 When the South Korean government in 2017 changed from rule by the conservative party to the liberal Democratic Party, the newly elected President Moon Jae-in further changed the bilateral relationship by denouncing the 2015 Agreement.Footnote 41 From the end of 2018, tensions became even greater when the Supreme Court of Korea made a judgement requiring present-day Japanese companies to compensate Korean victims of forced labor at their wartime facilities.Footnote 42

The tension from these historical issues spilled over to other bilateral matters. Japan initiated economic sanctions against South Korea, deleting the country in August 2019 from a “white list” of nations with fast-track trade status offering preferential treatment for the import of sensitive Japanese-made goods.Footnote 43 South Korea responded tit-for-tat, tightening import restrictions on Japanese food, allegedly because of radioactive contamination from the 2011 Fukushima nuclear meltdown.Footnote 44 In addition, Korean civil society started a “No Japan” movement to boycott popular Japanese products and cease travel to Japan.Footnote 45 This action spread nation-wide and received strong support, especially from younger Koreans, continuing until the end of 2020.Footnote 46 Japanese companies saw sharp drops in sales, and major Japanese companies including Nissan, Uniqlo, and Olympus eventually closed their Korean operations. However concern also grew in South Korea over the negative impact of these shutdowns on local employment and economies.Footnote 47

These disputes over historical understanding also spilled over to trilateral security cooperation. In August 2019 South Korea announced it would terminate its intelligence-sharing agreement with Japan, the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA).Footnote 48 The United States had pushed for GSOMIA in 2016 to enable a coordinated response to North Korea’s military threat, and the US successfully pressured South Korea to conditionally extend the agreement,Footnote 49 while Japan announced it would resume negotiations with South Korea over export controls.Footnote 50 Even so, the bilateral relationship remained deadlocked until newly elected president Yoon Suk Yeol sought a dramatic breakthrough in 2022. This materialized in March 2023 with a historic summit between Yoon and the Japanese Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida. Yoon called for a bilateral “grand bargain” addressing issues of security, economy, and history.Footnote 51

After a series of follow-up meetings, the Korean government became less vocal about historical issues including forced labor and Comfort Women. Notably for our inquiry, the substance and tone of discussions at UNESCO concerning the Meiji Industrial Revolution Sites changed significantly. At the September 2023 annual WHC meeting in Saudi Arabia, the Committee acknowledged “the new set of measures” undertaken by Japan as well as “several additional steps” in response to the Committee’s previous strong requests. It “underline[d] the importance for the State Party [Japan] to continue the implementation of its commitments in order to enhance furthermore the overall interpretation strategy of the site,” and then in a neutral tone it encouraged continuing dialogue between the concerned State Parties.Footnote 52 Compared with the previous decisions, which spoke of “strong regrets” at recent Japanese action or “strongly encourage[ing]” further Japanese efforts, this statement reflected much less protest from Korean side.Footnote 53 That said, the report does not specify what the new measures were, nor do we see evidence of any significant change in the Japanese interpretation of the history of wartime labor.

Conflict in the memory of the world (MoW) nomination

Chinese nomination of the documents of nanjing massacre

As of this writing in 2024, the bilateral confrontation over Japan’s industrial revolution World Heritage Sites had abated. The situation is one of suspended and latent conflict. However conflict over historical understanding among Japan, South Korea, and the PRC continues in another UNESCO arena, the Memory of the World (MoW) program, launched in 1992 in the wake of the Yugoslavian war to preserve vulnerable documentary heritage of global significance recorded in various forms.Footnote 54 This program has played an important role in making the documentary heritage of human rights more visible.Footnote 55 However, and inevitably given the structure of UNESCO, since its inauguration the International Register of the MoW program has come to be considered an official, international recognition of the historical narrative of particular nations.Footnote 56

In 2014, China nominated “Documents of the Nanjing Massacre” from December 1937 into January 1938 for inscription on the MoW Register. The nominated records documented the massacre of many tens of thousands (perhaps hundreds of thousands – the number is disputed) of Chinese people by Japanese soldiers in Nanjing. The Japanese government protested loudly, criticizing what it called obvious problems with the integrity and authenticity of the documents and condemning the PRC for politicizing UNESCO.Footnote 57 Yet the International Advisory Committee (IAC) charged to evaluate MoW nominations recommended inscription, and with the endorsement of the UNESCO Director General in October 2015 the documents were added to the International MoW Register. This decision was possible despite Japanese opposition because, unlike the World Heritage Sites, at that time the expert committee made recommendations to the UNESCO Director, not to an intergovernmental body like the World Heritage Committee.

Japan’s contradictory position and push for the reform of MoW program

Although the Japan government was unhappy with this result, that same year it benefited from the expert-driven structure of this program when it submitted a MoW nomination dossier consisting of drawings and written records of the internment and repatriation experiences of Japanese from the Soviet Union from 1945 to 1956. Along with the Nanjing Massacre documents, in 2015 these were inscribed in the MoW Register as the Return to Maizuru Port Documents over the strenuous objection of Russia. Its government very differently interpreted the status of these men, claiming the Japanese soldiers were lawfully detained prisoners of war. The Russian objection failed, and the Documents of Return to Maizuru Port were added to the MoW Register.Footnote 58

UNESCO’s expert evaluators deemed the Maizuru Documents a unique collection of materials offering evidence of the abusive experience of internment and the repatriation, which contributed to a more comprehensive understanding of wartime and post-World War II history.Footnote 59 Given that “historical importance” is a primary criterion for MoW nomination,Footnote 60 UNESCO’s decisions to inscribe both the Nanjing and Maizuru Documents in the MoW register strike us as well-grounded and desirable. Both sets make clear the brutality of war and deliver messages that such atrocities must not be repeated. The Japanese government objecting to the Nanjing inscription, and its blame of China for politicizing UNESCO, while it simultaneously supported the Maizuru nomination, is inconsistent at best.Footnote 61

But inconsistency did not stop Japan from escalating its financial and political pressure on UNESCO. Immediately upon the inscription of the Documents of Nanjing Massacre, fearing the nomination of additional documents related to Japanese wartime aggression, Japan suspended its regular annual contribution to UNESCO and requested that UNESCO reform the MoW selection process. At the time, Japanese funds accounted for 11 percent of UNESCO’s budget,Footnote 62 making it the biggest donor since the United States had halted its contribution to UNESCO in protest at the 2011 admission of Palestine as a UNESCO member. With the hard power of money, the Japanese government sought to align UNESCO with its view of the history of imperialism and war.Footnote 63

The Director General of UNESCO, Irina Bokova, followed the expert body recommendations and endorsed the Nanjing and the Maizuru inscriptions but faced criticism in both cases. Critics claimed she supported the Nanjing documents to win China’s backing for her effort to become a future UN Secretary-General.Footnote 64 And UNESCO’s financial difficulties forced her to concede to Japan’s call for reform of the MoW program. At the end of 2016, pleased that the reform process had begun, the Japanese government resumed annual contributions to UNESCO.Footnote 65

Indeed, Japanese pressure led to a significant transformation of the MoW program, which until this time had been well known for its openness to non-State actors. Any individual or organization could nominate dossiers for inscription, which were assessed only by the expert International Advisory Committee (IAC), and finally endorsed by the UNESCO Director-General.Footnote 66 The contrast to the World Heritage List, whose inscriptions were decided by a World Heritage Committee of 21 State Parties (to be sure, guided by the recommendation of expert advisory bodies) was clear: member states could not intervene in the MoW process. The Japanese government argued this system lacked transparency: MoW expert advisors might be too reliant on the perspective of the nominator.Footnote 67 Japan also argued that the expertise of the IAC members, mostly library and archival experts and not professional historians, was insufficient to allow them to make valid judgments.Footnote 68

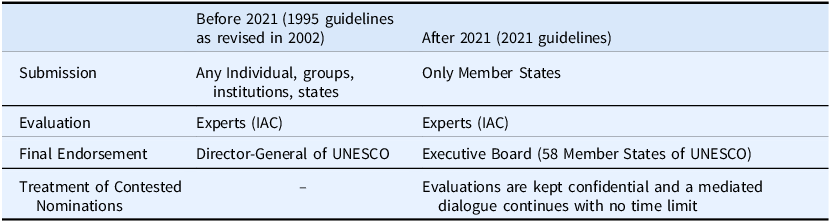

In November 2015, at the request of the UNESCO General Conference, a group of experts reviewed the General Guidelines of the MoW program and in October 2017 presented its conclusions to the UNESCO Executive Board. Tension between South Korea and Japan over the MoW program was high at that time due to the Comfort Women document nomination discussed below. This fraught context led UNESCO to move very slowly.Footnote 69 It suspended new MoW nominations and in consultation with member states undertook a comprehensive review and report on the MoW program. Not until September 2019 did an open-ended working group including IAC experts finally present its report to the UNESCO Executive Board. And in a setback for transparency, the Executive Board decided to carry forward this effort with a new closed working group. In April 2021, the Board finally accepted the recommendations to dramatically revise the MoW Guidelines (Table 2).Footnote 70

Table 2. Comparison of the guidelines of the MoW program before and after 2021

Three key changes are clear: applicant eligibility narrowed dramatically, excluding individuals, NGOs or any non-state institution unless they first presented the nomination to a national government body, which would forward the nomination; the final decider was changed from the UNESCO Director to the Executive Board of member states; contested nominations were further discussed behind closed doors with no time limit. Only Member States could now apply for the Register through their National UNESCO Commissions, for the most part, government bodies of Member States, or through a National MoW Committee.Footnote 71

This reform aligned the MoW program with other UNESCO programs such as the Man and Biosphere Reserve and Geoparks, whose international lists are endorsed by the UNESCO Executive Board of Member States. Probably the most controversial change was the new treatment of contested nominations.Footnote 72 Japan had pushed strongly for the mechanism of ongoing dialogue with no time limit. Critics reasonably claimed that this new process allowed “a nomination [to be] rejected purely because an objecting party dislikes it.”Footnote 73 No such procedure — giving de facto veto power to states – exists for any other UNESCO program of authorized lists.Footnote 74

Competing nominations for the comfort women documents and their negotiations

In 2014, along with Nanjing Massacre documents, China submitted “Archives about “Comfort Women” for Japanese Troops” to the MoW program. The expert committee (IAC) deferred the application until 2015, calling for multiple countries to join the nomination.Footnote 75 In late 2014, a South Korean NGO, Asia Peace & History Institute, swiftly mobilized NGOs in eight countries with records related to the Comfort Women. Fourteen organizations from South Korea, China, Indonesia, Japan, the Netherlands, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Timor-Leste established an international committee to pursue a joint nomination.Footnote 76 Since this joint nomination, led by a Korean NGO, was submitted, the issue of the Comfort Women nomination has increasingly become a matter of bilateral relations between South Korea and Japan. Although the Korean government under President Park sharply reduced financial support for this effort upon reaching agreement with Japanese Prime Minister Abe to “irreversibly” settle the Comfort Women issue in December 2015,Footnote 77 this group managed to submit an application for MoW registration in 2016. In early 2017, the expert Register Sub-Committee (hereinafter, RSC) of ICA deemed this submission to be an “irreplaceable and unique” application.Footnote 78

Meanwhile, four Japanese and American NGOs submitted a rival application it called “Documentation on “Comfort Women” and Japanese Army Discipline.” Their documents overlapped somewhat with the those in the competing joint nomination,Footnote 79 but their interpretation of the documents different fundamentally, arguing that the documents showed the Comfort Women contracted voluntarily as prostitutes for the Japanese military between 1938 and 1945.Footnote 80 The Japan-led group, supported by right-wing politicians, requested that UNESCO mediate between the nominations.Footnote 81 The Japanese government, on guard due to the inscription of Nanjing documents, lobbied forcefully on behalf of a principle of “dialogue” to both experts in the IAC,Footnote 82 and the Executive Board of UNESCO.Footnote 83 This pressure of course aligned with the Japanese government push to transform the MoW program into a state-driven system. In the end, the IAC referred both nominations to the Director-General, asking that office to facilitate dialogue among the nominators.Footnote 84 South Korea and China both expressed disappointment at this decision and expressed their wish for further steps toward successful nomination.Footnote 85

Since the end of 2017, however, there have been no bilateral meetings between the parties concerned with these opposing nominations. Although the Documents on Comfort Women were submitted in 2016, five years before the revision of the MoW Guidelines, the ongoing negotiations over these documents are following the new guidelines, with no time limit in place. Since 2017, facilitators have held only a few meetings to discuss possibilities for a joint nomination and the conditions for any bilateral meetings that might be held.Footnote 86 With the defensive Japanese attitude and no active role by the UNESCO Secretariat, no dialogue took place for seven years, until a first bilateral meeting was scheduled to be held in Paris within 2024 (however, as of this writing in February 2025, the meeting has yet to take place).Footnote 87 Given the far more positive WHC assessment of the Meiji Industrial Sites in 2023, reflecting the Japan-South Korea “grand bargain,” some compromise might be reached on this standoff. However, given the current political situation, discussed below, further backlash is likely if the South Korean government pressures domestic NGOs advocating for the MoW listing of the Comfort Women documents to adopt a more conciliatory approach toward Japan. Consequently, such an outcome appears unlikely.

Observation and analysis

Clearly the conflicts among Japan, South Korea, and China over the World Heritage and MoW nominations Register reflect profound unresolved differences in the understanding of the legacies of colonial rule and war in the first half of the twentieth century among states and civil society actors. Given the role of state parties in the UNESCO heritage programs, it is inevitable that nomination processes reflect the conflicting interests – both international and domestical-- of different actors. We now turn to discuss this wider context.

The limits to UNESCO’s role in international state politics

It is no secret that the governments of East Asian nations have conflicting views of their shared modern history. It is also important to recognize that these views, and the way they have been mobilized to serve national interests, change over time. For many years the government of China played down its historical experience as a victim of Japan, instead emphasizing China’s ultimate victory in a heroic War of Resistance.Footnote 88 This began to change from the 1980s; the official Chinese line shifted to a policy of boosting patriotism by depicting the nation as the victim of foreign imperialism.Footnote 89 In the 2010s, China began using this perspective to strengthen its ties with South Korea and weaken the US-South Korea-Japan alliance.Footnote 90 Thus, during his visit to Seoul in July 2014, President Xi Jinping stressed that “China and South Korea have similar experience in history and shared interest on the issue of history related to Japan.”Footnote 91 In 2015 this shared understanding led China to join the multi-national nomination of Documents on Comfort Women.Footnote 92 That same year, the PRC sided with South Korea to oppose the inscription of the Meiji Industrial Revolution Sites.

It is also well-known that divergent interpretations of Korea’s experience under Japanese colonial rule have undermined Japan-South Korea economic and security cooperation. Since decolonization, political parties in South Korea have taken different approaches to conflict with Japan over history issues. Especially in the last decade-plus, changes of presidential administrations in South Korean have shaken bilateral relations. Although President Park Geun-hye (February 2013–March 2017) tried to strike a balance between South Korea’s relations with China and Japan, the Korean criticism of the Meiji Industrial Sites nomination was fierce. This criticism became even harsher when President Moon of the Korean Democratic Party came to power (May 2017–May 2022). On his watch, disputes over the history embedded in heritage nominations spilled over into economic and security conflicts. But most recently, with the return of a conservative government under President Yoon (March 2022–present), and in part due to American pressure, the intensity of historical disputes has diminished, and the two governments are working more amicably on security and economic relations.

The Japanese position on some of the history issues at stake in these nominations, especially concerning the Comfort Women, was more conciliatory in the early 1990s (although not before). But since the early 21st century when it first began discussing and pushing for these heritage nominations, the government of Japan has been quite consistent in its stance concerning colonial and wartime history, including its positions put forward to UNESCO.Footnote 93 Reflecting long-held beliefs, Abe Shinzō made historical revisionism a central part of his domestic and international policy, including public diplomacy at UNESCO.Footnote 94 He expressed doubts about the 1993 Kono Statement which apologetically recognized the Japanese government’s responsibility for the comfort woman system, and on his watch, the Ministry of Education minimized discussion of the Comfort Women in secondary school textbooks.Footnote 95 His visits to Yasukuni Shrine, where the war criminals convicted in the occupation era International Military Tribunal for the Far East were enshrined, provoked South and North Korea and China.Footnote 96 The “Japan is Back” slogan aligned with his government’s campaign against China and South Korea over historical issues such as the Comfort Women and Nanjing Massacre.Footnote 97 At UNESCO, as we have seen, his administration pushed hard against South Korean and Chinese MoW nominations related to the colonial and wartime past concerning Comfort Women and the Nanjing Massacre.

Discord between Japan and South Korea worried the United States as their trilateral alliance grew more important in the face of a rising China. In 2015, the United States welcomed the Japan-South Korea compromise agreement that allowed the Meiji industrial sites to win world heritage status.Footnote 98 But when Korean courts found Japanese companies liable for reparations to wartime drafted laborers, a new round of even deeper tension unfolded between Japan and South Korea spilling over into the trade and security realms, leading the US to press the two governments to lower the temperature of their history disputes.Footnote 99 It was in this context that the three countries signed a trilateral agreement in August 2023 putting aside contention (at least for the time being) over their disputes over shared history.Footnote 100

Amidst tensions over history, economy, and security, the UNESCO secretariat could not play a consistently active role as a peace-builder, its chartered mission.Footnote 101 In the case of the Japanese Meiji Industrial Revolution Sites nomination, initially the UNESCO secretariat working closely with the German chair of the WHC clearly conveyed to the Japanese delegates the pressure from international society. These mediation efforts contributed to the compromise agreement. But that same year, the inscription of the Documents on Nanjing Massacre led Japan to suspend its financial support for UNESCO, forcing UNESCO to compromise with Japan so as to prioritize financial stability. An additional factor was a 2017 change of leadership in UNESCO, from Irina Bokova, former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Bulgaria, to Audrey Azouley, former Minister of Culture and Communication of France. Bokova had acted decisively, for instance to bring Palestine into UNESCO, but she had been criticized for losing first US and then Japanese financial support due to UNESCO actions. Those who elected Azouley hoped that her prestige as a French person would help her mitigate political confrontations within UNESCO.Footnote 102 However the weak role of the UNESCO secretariat in the process of reforming the MoW system makes clear she did not play an active role in moderating East Asian heritage disputes.Footnote 103

Domestic political agenda limiting heritage interpretation

Japan’s nationalistic narrative in various UNESCO forums has been mirrored in the governance of heritage at the local level. A recent example is the decision of the Gunma prefectural government to tear down a cenotaph mourning the deaths of Korean wartime laborers at a military facility in that region.Footnote 104 When a government brings a domestic historical narrative into the international arena it is all the more likely that the dark aspects of that history are ignored. Governments, and many citizens, want to show the world the bright, glorious side of heritage. Japan’s nomination of the Meiji Industrial Revolution Sites paid virtually no attention to the widespread use of convict labor in the late 19th century,Footnote 105 and none at all to the frequent labor struggles at these sites.

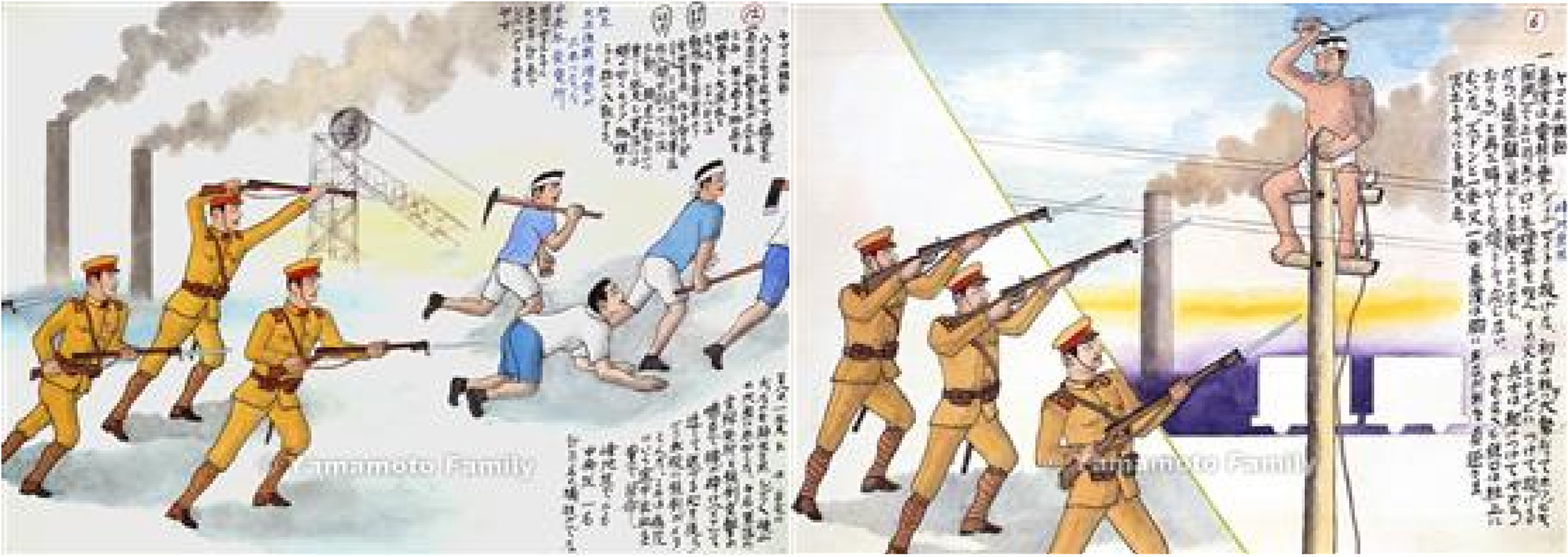

Ironically, the Sakubei Yamamoto Collection, separately and earlier (2011) inscribed in the MoW Register, includes scenes of the 1918 rice riots by coal workers in Kyushu (Fig. 2),Footnote 106 but these were not included in the Meiji sites nomination file, although the Japanese nomination used other images from the Yamamoto Collection. Moreover, by limiting the time span to the Meiji Era, the nomination also overlooked the largest labor dispute in Japanese history, at Mitsui Miike in 1959–60.Footnote 107

Figure 2. (left) Rice Riot in Yahata Pit (catalog no. 556) and (right) Rice Riot in Mineji Pit (catalog no. 561). (Source: Tagawa City Coal and History Museum).

Bringing a narrow view of national heritage to international attention risks mobilizing the prestige of UNESCO to marginalize alternative local narratives. That said, in the Japanese case, outside the official narrative at the World Heritage Sites, negative aspects of industrial heritage have been presented clearly to the public. Nearby the Miike coal mine, separately from but close by the official world heritage sites, one finds memorials for Meiji era convict laborers and Korean and Chinese wartime forced laborers, commemorations of the 1959–60 labor dispute, and a cenotaph mourning the many hundreds who died in a 1963 explosion. Established by civil society organizations, these memorials predated the World Heritage Site designation.Footnote 108 Throughout Japan, well over 100 cenotaphs honor the memory of Korean wartime laborers, erected by coalitions of Korean residents in Japan and Japanese supporters.Footnote 109 Some of these groups worked with South Korean victims of forced labor to bring lawsuits and organize commemorative events.Footnote 110 These initiatives continue.

That said, the divisive politics of the World Heritage system can lead to backlash against such projects. For example, a person apparently connected to a right-wing political group sprayed the words “All a lie” on a cenotaph for Koreans who died under the forced labor regime in the Miike coal mine in 2015.Footnote 111 This graffiti was removed, and the cenotaph still stands. But the possibility remains that a top-down, centralized, and nationalistic process of defining heritage will limit more inclusive and diverse heritage interpretations and reduce prospects for reconciliation.

Prospects and the way forward

Unchanged narratives and suspending contested nominations

With the revitalized South Korea-Japan-US alliance and increasing rivalry between China and US, the heritage war among these three East Asian countries, in particular between Japan and South Korea, has entered a new phase. A clear sign of this came at the September 2023 WHC meeting, where the confrontation over the Meiji Industrial revolution sites was far less intense than before. It is also possible that negotiation over the Documents on the Comfort Women may resume in a less confrontational way. The PRC is no longer playing an active role. It seems to have abandoned its 2014 agreement for bilateral cooperation on these issues with South Korea.

However, the revisionism in Japan that downplays or denies the existence of forced labor or the trafficking inherent in the Comfort Women system will likely be persistent in both domestic and international politics. Dissenting voices will continue to be ignored in heritage interpretations put forward by the central government. For example, the State of Conservation report Japan submitted to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre in December 2022 presented no substantial change from previous reports written when Japan-South Korea relations were under the greatest strain.Footnote 112 That report’s phrasing notes that laborers were “requisitioned” rather than “forced to work” (although by definition “requisition” is mandatory). It further notes that victims included “all nationalities,” that conditions of work were the same for all, and that there was “no slave labor.”

Also, it remains the case at the Industrial Heritage Information Center – opened in Tokyo in 2020 as Japan’s response to the WHC request for heritage interpretation allowing an understanding of the “full history” in the sites – that one finds no testimonies from foreign laborers themselves, whether Korean, Chinese, or Allied POWs, who in the words of the 2015 inscription, “were forced to work against their will.” The exhibit presents a one-dimensional narrative, focused almost exclusively on Hashima (Battleship Island) with testimonies denying that forced labor happened, from Japanese residents who at the time were too young to have held any authority or too young to have actually been workers.Footnote 113 A plaque on the wall at the entrance to the exhibition center uses the term “forced to work against their will,” and QR codes at the center in Tokyo allow visitors to read the 2015 Japanese statement to the World Heritage Committee promising a fuller interpretation strategy, but the Center’s basic stance is denial and omission.

The Japan-South Korea confrontation over UNESCO nominations is thus ongoing. Further backlash is likely if President Yoon pressures the domestic NGOs seeking MoW listing for the Comfort Women documents to take a conciliatory approach to Japan, as occurred after the 2015 Park-Abe Comfort Women Agreement. In November 2023, South Korea was elected one of the 21 members of the WHC again after leaving in 2019, and Japan is a continuing member (2021–2025). South Korea was also re-elected a Member State of the Executive Board that has the final say in the MoW Register, where it joins Japan, China, and the US. In the meantime, Japan nominated the Sado Gold Mines for World Heritage status, for consideration at the 2024 WHC. Some of these mines also used wartime conscripted (forced) labor, but the Japanese nomination of Sado focused solely on the early modern era (seventeenth through mid-nineteenth century), thereby not addressing wartime labor.Footnote 114

In June 2024, ICOMOS deemed the Sado mines worthy of World Heritage status, with two contradictory reservations that placed the nomination on hold. First, in some of the nominated areas the only authentic elements were from the modern era, so ICOMOS made a primary recommendation to exclude these areas. Second, ICOMOS made an “additional” less binding recommendation that the “whole history…throughout all periods of mining” be presented to visitors.Footnote 115 Japan swiftly implemented a series of measures to satisfy the primary recommendation, removing the exclusively modern sites from the nomination. It took partial steps to satisfy the “additional” recommendation. Most notably, and in sharp contrast to the statements about wartime foreign labor at the Meiji Industrial Revolution sites and the Tokyo Information Center, the revised nomination acknowledged that the Korean workers faced discriminatory treatment. It asserted these workers were assigned to more dangerous jobs than their Japanese counterparts, that they were required to work as many as 28 days each month, that they engaged in labor disputes, and that they frequently tried to escape and were imprisoned if caught. The Japanese delegation also announced that an exhibit (tucked away on the third floor of the historical museum in the town of Aikawa, about 2 kilometers from the World Heritage Site itself) had already been changed to make these points. It also promised to hold an annual ceremony on the island to honor the sacrifices of all the Sado miners.

This revised nomination won unanimous approval (including from South Korea), at the July 2024 meeting of the World Heritage Committee in New Delhi. Although the Japanese recognition of the discriminatory harsh treatment of Korean workers was a significant shift, the Korean side also made a major concession, dropping its insistence that Japan’s official interpretation use the words “forced labor” or even the slightly softer phrasing of “brought against their will” and “forced to work,” as used at the Meiji sites. The public reaction in each country was divided in predictable ways. Supporters of President Yoon welcomed the resolution; opponents blasted the retreat from insistence on the term “forced labor.”Footnote 116 The Japanese right-wing media lamented that the Japanese side addressed wartime conditions at all for a nomination focused on the early modern era, while the liberal press gave the result high marks.Footnote 117 The issue remains unsettled. As promised Japan did hold a ceremony at the Sado Gold Mines in November 2024, which recognized that Japanese and Koreans lost their lives, but did not describe the Korean victims as forced labor.Footnote 118 But in advance of this ceremony, the Japanese government representative was reported in the Japanese media (this later turned out to be incorrect) to have visited the Yasukuni Shrine to Japanese war dead in 2022. In protest, the Korean delegation held its own separate memorial service.Footnote 119

Further, Japan’s latest State of Conservation report of the Meiji Industrial Sites, submitted to the UNESCO World Heritage Centre in December 2024, remains largely unchanged from previous reports. It continues to assert that all individuals were treated equally and endured hardships together, without acknowledging discriminatory treatment of Korean, Chinese, or POW forced labor.Footnote 120 This lack of recognition has intensified criticism of President Yoon’s diplomatic approach toward Japan, particularly regarding historical reconciliation. In addition, as of March 2025, President Yoon faces a significant domestic political crisis, with the possibility of impeachment following his unexpected declaration of martial law in the previous month.Footnote 121 This political instability further complicates the prospects for future diplomatic engagement between South Korea and Japan on UNESCO heritage issues. The US may once again try to persuade both allies to check China at UNESCO. However, the success of this effort is uncertain as well, particularly given the possibility that President Trump’s engagement with UNESCO might wane, considering his 2018 decision to withdraw the US from the organization.Footnote 122

The way forward: possible contributions by different non-state actors

The simple way to resolve these conflicts over UNESCO heritage nominations is to acknowledge multiple memories based on facts that allow for different interpretations. This approach worked for the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, nominated for world heritage status in 1996. At that year’s WHC meeting, the US objected to the lack of a discussion of the causes of the war, without which the context for the dropping of the bomb would not be fully understood. The Chinese objected that Japan’s role as the aggressor was not mentioned; the sole focus was on the Japanese as victims.Footnote 123 In response, the Japanese curators tried to introduce the complex historical context. For example, the exhibition panels note the presence of about 20,000 Korean laborers killed by the bomb: “these [victims] included tens of thousands of Korean workers and their families who, due to the labor shortage, were brought by force to Japan to work in military factories.”Footnote 124 In addition, as far back as 1970 a group of Korean residents in Japan and local Japanese volunteers erected a cenotaph for these laborers just outside the Park and in 1999 this monument was moved inside the Park.Footnote 125

The Hiroshima example demonstrates that multiple memories can co-exist in official and unofficial contexts through the participation of multiple stakeholders. Grand political bargains can also provide pivotal momentum to resolve these disputes, but high-level agreements can fail to gain civil society support. To present varied narratives to the public, the ongoing involvement of civil society is crucial. At both Miike and Hiroshima, steadfast local civil society action complemented state-driven, institutional heritage-making and countered one-sided historical interpretations.

In addition, civil society can contribute to dialogue over history that transcends politics by supporting joint research on historical issues, leading to mutual understanding and cooperation. A good example is the collaboration between South Korean and Japanese groups working to repatriate the remains of wartime Korean laborers.Footnote 126 Civil society cooperation began in 1997. State-level cooperation began later, in 2005. Research by civil society groups can bring to light additional evidence and point the way to more balanced historical interpretations at heritage sites. According to the foremost South Korean expert on wartime forced labor, even now both Japanese and Koreans have uncovered only one-third of this tragic history.Footnote 127

These actions can influence UNESCO – which tends to stay quiet in the face of conflicts among big donors – to act. When NGOs petition UNESCO, relevant State Parties need to respond, and UNESCO becomes better aware of the issues at stake. If UNESCO leaders summon the will, they can provide strong mediation during confrontations over heritage nominations among its member states, as happened during the conflict over the inscription of the Meiji Industrial Revolution Sites. While mechanisms to encourage further UNESCO involvement are needed,Footnote 128 UNESCO National Commission, whose mandate is to facilitate dialogue between civil society and government and the government and UNESCO,Footnote 129 can also be an effective coordinator.

In the East Asian UNESCO heritage nominations analyzed in this paper, the state parties politicized historical disputes, which spilled over to hard power issues of economy and security. In addition, changes in political relations among countries shaped the outcome of these cases. As heritage contests unfold among States, memories and voices from civil society can easily be ignored, making it difficult to understand the full history at stake. More involvement of civil society is needed, and UNESCO needs to play a more active role by listening to these voices and mediating state-led negotiations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Fulbright Korea and the U.S. Institute of International Education (IIE) for providing us with the valuable opportunity to conduct this joint research. We are also deeply grateful to the Harvard University Asia Center, particularly Tenzin Ngodup and Jorge Espada, whose support was instrumental in hosting Kim. Our appreciation extends to attendees of the Harvard University Asia Center’s seminar in December 2023, where Kim presented and Gordon moderated, for their valuable feedback in shaping this paper. Finally, we sincerely thank the anonymous reviewers for their time and insightful comments, which have significantly enhanced the quality of our work.

Author contributions

Dr. Jihon Kim is a Visiting Scholar at the Harvard University Asia Center and a former Fulbright Postdoctoral Fellow at the Center (2023–2024). She also serves as the Chief of Policy at the Korean National Commission for UNESCO and as an Adjunct Professor at the Graduate School of World Heritage Studies at Konkuk University. As a Research Fellow at the Institute of International Studies at Seoul National University, she conducts various research focused on international cultural heritage law and policy, with a particular emphasis on historical disputes between states and the role of non-state actors in heritage governance.

Prof. Andrew Gordon is Lee and Juliet Folger Fund Professor in the Department of Department of History, Harvard University. He has written books on the history of labor in Japan, as well as a general interest textbook, A Modern History of Japan. He is currently working on a study of the public history of Japanese modern industry, giving particular attention to coal mining and the wartime exploitation of foreign labor.

Competing interests

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the organizations to which they belong. This manuscript was written based on personal observation and research.