Introduction

In the context of the current state and legal development of Kazakhstan, it is highly relevant to fulfil the tasks of preventing and combating crime. Compliance with the applicable criminal procedure legislation, including pre-trial investigation and determination of investigative tactics, all contribute to the achievement of the goal of fighting crime. Juveniles form a special group that differs from adult criminals both in the nature and degree of social danger of their actions and their characteristics. These features include insufficient social maturity and incomplete intellectual and volitional development, which in some cases are aggravated by inadequate protection of their rights. This specificity requires a special approach to solving practical issues related to bringing minors to criminal liability, imposing and executing punishment, as well as exemption from liability and punishment. Currently, interrogation as an investigative action is central to ensuring a full and objective investigation, as it is conducted in every criminal proceeding. Interrogations of minors are of particular relevance in this context. Therefore, it is necessary to address the interrogation of minors and juveniles, which requires the use of special tactical approaches.

The effectiveness of interrogations of minors largely depends on the investigator’s ability to account for the age and intellectual characteristics of the interrogated person, as well as to establish the necessary level of psychological contact. At the moment, the potential of the system for protecting the rights and legitimate interests of minors subjected to interrogation cannot be fully realized due to the insufficient level of legal regulation and the lack of legal clarity in several provisions of the national criminal procedure legislation. At the stage of pre-trial investigation, the interrogation of minors becomes a critical point, as it is at this time that violations of their procedural rights are most often observed. These violations can significantly affect the quality of the evidence collected and, consequently, the fairness of the trial. It is important that all procedural norms are observed during interrogations and that the psychological and social characteristics of minors are covered, which requires appropriate legal regulation and the use of special tactical techniques. Thus, the issue of juvenile suspects, witnesses and victims is characterized by certain peculiarities due to age and social, moral, psychological and tactical aspects. These features emphasize the need to conduct criminal procedural and forensic research on a range of issues related to the interrogation of minors in criminal proceedings.

One of the important aspects of this topic is to understand the specifics of the legal regulation of the interrogation of minors, which directly affects the observance of their rights and legitimate interests in criminal proceedings. In this context, it is worth mentioning the scholars who have studied this issue. Thus, Chistyakov and Naurzalieva (Reference Chistyakov and Naurzalieva2020), Smatlaev, Baimoldina, and Nagornov (Reference Smatlaev, Baimoldina and Nagornov2022) and Vasilievna and Galymovich (Reference Vasilievna and Galymovich2021) noted that legislative changes regarding the basis of criminal liability of minors in the Republic of Kazakhstan have led to qualitative transformations in the criminal law relations between juvenile offenders and State authorities, requiring a new scientific understanding. However, these studies do not fully address the issues related to the adaptation of interrogation techniques to the individual psychological characteristics of juveniles and also do not sufficiently cover the problems of law enforcement practice in this area.

Musabaev, Abenova, and Zhetpisov (Reference Musabaev, Abenova and Zhetpisov2023) drew a parallel between the inappropriate behaviour of parents and other legal representatives and the misbehaviour of children from disadvantaged families. They substantiate the need to introduce administrative liability for parents or other legal representatives for administrative offences or criminal offences committed by their children. Their research emphasizes that Kazakhstan is implementing a set of measures aimed at enhancing the authority of the family institution, promoting the best family traditions and recognizing the merits of the family in raising a physically and morally healthy generation. Taizhanova and Temirgazin (Reference Taizhanova and Temirgazin2024) analysed the forensic characteristics of criminal offences committed by minors. Their research included analysis of the traces at the crime scene, studying the environment in which the offence occurred, identifying motives and possible suspects, and analysing the social, psychological and educational conditions that contributed to the offence. However, these studies miss specific aspects of the tactics of interrogating minors. In particular, they do not sufficiently consider psychological techniques and approaches that can increase the effectiveness of interrogations while respecting the rights of minors. Moreover, the analysis of international experience and standards, which could enrich the law enforcement practice of Kazakhstan and other countries, is insufficient.

Therefore, the study aims to substantiate the theoretical and legal foundations of the tactics of interrogation of minors in Kazakhstan, as well as to identify promising areas for improving the legal regulation of interrogation of this category of participants in criminal proceedings in the Republic of Kazakhstan. The following tasks were formulated and addressed to achieve the set objectives:

-

1. Define the concept and essence of interrogation as a procedural investigative action in criminal proceedings involving minors;

-

2. Analyse the current state of criminal procedural support for the interrogation of minors in Kazakhstan and identify problems arising in law enforcement practice;

-

3. Consider the specific features of the tactics of interrogation of minors;

-

4. Identify common tactical techniques for interrogating minors;

-

5. Identify problems associated with the implementation of a system of tactical techniques aimed at establishing psychological contact with minors.

Materials and Methods

The tactics of interrogation in criminal cases involving minors is one of the most significant and complex tasks in criminal procedure. The study analysed the legal acts regulating the interrogation of minors in criminal cases under the current legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan, which was used to assess the current state of the problem and identify possible ways to improve it. To comprehensively understand and substantiate the issues under study, the rules of various legal sources were used, including the following: Criminal Procedure Code (CPC) of the Republic of Kazakhstan;Footnote 1 Normative Decision of the Supreme Court of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 6;Footnote 2 Law of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 591;Footnote 3 United Nations General Assembly Resolution No. 45/113;Footnote 4 United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice (The Beijing Rules);Footnote 5 and United Nations Guidelines for the Prevention of Juvenile Delinquency (The Riyadh Guidelines).Footnote 6

In defining the theoretical and legal foundations of the tactics of interrogation of minors in Kazakhstan, the study formulated the general forms, properties and key features of interrogation under the current legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan. A comparative analysis of the literature identified problematic issues that need to be addressed. The use of the principles of comprehensiveness and complexity identified ways and forms of improving the current legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan to update the legal provisions relating to the interrogation of minors.

The study of the place of interrogation among other investigative actions in the investigation of a crime committed by a minor has set out different concepts of its understanding and legal nature. The study also identified the factors influencing the regulation of interrogation of this category of criminals in criminal proceedings, as well as the current problems in this area at the present stage. The key legal acts regulating the protection of the rights of minors as key participants in interrogation under the legislation of the Republic of Kazakhstan were organized and systematized. This was used to assess the current state of the problem and identify possible areas for improving legal regulation in the face of global challenges. The analysis of law enforcement practice and existing legal regulation problems was used to formulate key conclusions and recommendations for improving the effectiveness of investigations of such crimes in the context of interrogations.

The study of interrogation tactics in criminal cases involving minors has revealed significant areas for improving legal and forensic practice. An analysis of the legal aspects of interaction between law enforcement agencies and forensic experts in this area identified the main needs and structures that ensure effective interrogations. The use of various scientific and legal methods, such as systematic, formal legal, formal logical and descriptive analysis, provided a comprehensive understanding of the current state of the legal regulation of the interrogation of minors. This identified potential problems and proposed ways to solve them, contributing to the improvement of law enforcement practice and the level of legal protection of minors.

The study of the legal aspects of interrogation tactics for minors identified key needs, such as improving the legal framework, training investigators and ensuring access to specialized interrogation techniques. In addition, the analysis showed the importance of creating specialized units within law enforcement agencies and active cooperation with international organizations to share best practices and technologies.

Results

Currently, criminal activity committed by or involving minors is a widespread phenomenon. Statistics show a significant number of offences involving minors (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Juvenile delinquency in 2020–2022 (number of cases).

Statistics demonstrate the frequency and types of crimes committed by juveniles, which is directly relevant to this study. This data determined the prevalence of various categories of offences among juveniles, which identified the main directions in the tactics of interrogation. The specifics of interrogation with different categories of juveniles can vary depending on the type of offence. For instance, when questioning minors for property crimes, a detailed questioning about the motives and circumstances of the crime is required. It is equally necessary to account for the social environment and peer influence. A psychologist is involved in the interrogation of violent offences to provide emotional support. More care should be exercised in dealing with traumatized minors, both suspects and victims. In each of these categories of crimes, interrogation tactics should be adapted to the age and psychological characteristics of the minors, as well as to the specifics of the crime itself (Bureau of National Statistics, Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan 2023). In addressing this issue, it is necessary to account for the fact that the psychological state of minors is particularly vulnerable, and their understanding of criminal offences and legal consequences is often not unambiguous and critical. In this regard, in criminal proceedings, the protection of the rights, freedoms and legitimate interests of minors requires increased attention from the State, as well as the international and European communities.

Notably, the concept of interrogation as an investigative action is not defined at the legislative level, and the purposes of its conduct are not formulated, unlike the regulation of inspection or search. Given the above, interrogation should be considered as one of the forms of obtaining evidentiary information through recording testimony, a procedural means of forming and verifying evidence. Interrogation is carried out following the requirements of Articles 208–218 of the CPC of the Republic of KazakhstanFootnote 7 and is a form of communication between people strictly regulated by procedural norms and social roles. This form excludes the possibility of psychological closeness between the participants, which creates additional communication barriers and does not contribute to the achievement of truth in criminal proceedings. These obstacles are particularly common when dealing with suspects, due to their defensive attitude. Analysing the provisions of Article 371 of the CPC of the Republic of Kazakhstan,Footnote 8 it should be noted that interrogation of minors cannot be conducted without the presence of a defence counsel. At the same time, an important gap is the lack of a legislative definition of the concept of interrogation of minors. This gap and related issues can be addressed by introducing a clear definition of interrogation.

Following the analysed studies, it is proposed to address the interrogation of minors as a procedural act, which is an information and psychological process of communication with minors regulated by the criminal procedure rules, aimed at obtaining information about facts or events relevant to establishing the truth in criminal proceedings. Such a definition of interrogation of minors most fully reflects the essence of this procedural action. According to the proposed definition, the purpose of interrogation of a minor is to obtain and record facts of direct relevance to criminal proceedings. In any case, the procedure for obtaining testimony from minors must be carried out following the procedure and within the time limits established by the CPC of the Republic of Kazakhstan.Footnote 9 When conducting an interrogation, a psychologist may recommend adjustments to the interrogation plan and draw attention to circumstances relevant to the study of the psychology of the interrogated person. The qualified assistance of a teacher (psychologist) can assist the interrogating official in assessing the relevance of the juvenile’s testimony to mental development. This is highlighted by many judges (Eshpanova Reference Eshpanova2017; Karagaev Reference Karagaev2018; Muldagaliev Reference Muldagaliev2017).

In analysing the above, it is worth emphasizing the importance of ensuring proper protection of the rights and legitimate interests of minors during interrogations and other investigative actions. Hence, such a provision is possible subject to a detailed definition of the specifics of the removal and replacement of the legal representative. Amendments to Article 371 of the CPC will lead to an improvement in the legal regulation of the interrogation of minors, and therefore the following changes are necessary:

-

Mandatory presence of a psychologist or teacher during the interrogation of minors should be ensured;

-

Special interrogation techniques adapted to the age and psychological characteristics of minors should be introduced;

-

Control over the observance of the rights of minors during investigative actions should be improved;

-

Provisions on the inadmissibility of pressure and the use of methods that can negatively affect the mental health of minors should be included.

These amendments will create a more humane and fair treatment of minors in criminal proceedings, contributing to the protection of their rights and legitimate interests.Footnote 10 In this context, it should be noted that the constitutions of foreign countries provide for special measures of legal protection of the rights of minors. For instance, Article 56 of the Constitution of the Republic of SloveniaFootnote 11 states that children are entitled to special protection and care. Human rights and fundamental freedoms are applied to children according to their age and maturity. Children are guaranteed special protection from economic, social, physical, mental or other exploitation and abuse. Another positive solution of legislative consolidation of special protection of minors in criminal proceedings, following international legal acts, can be seen in the example of Georgia. In particular, the CPC of GeorgiaFootnote 12 contains a separate Chapter XXVIII “Proceedings in Cases of Juvenile Delinquency”, which regulates the procedure for conducting criminal proceedings against this category of persons. According to Article 315 of the CPC of Georgia, the procedure for juvenile proceedings applies to persons whose criminal prosecution was initiated before they reached the age of 18 years. Upon reaching the age of 18 years, criminal proceedings against them will be conducted following the general procedure established by the CPC of Georgia. Additional attention should be devoted to the provision of Article 316 of the CPC of Georgia, which states that minors should be treated with special attention at all stages of the process.

It is necessary to account for the age of minors and special interest in re-socialization, as well as the promotion of re-education. In the course of criminal proceedings against minors, full compliance with the norms of international legal acts guaranteeing the rights of minors is mandatory. Thus, the legislation governing criminal proceedings against minors requires compliance not only with the provisions of the CPC of the Republic of KazakhstanFootnote 13 but also with international legal guarantees for the protection of the rights and freedoms of minors. The process of humanization and improvement has also affected the national legislation of Kazakhstan. As a result, the issue of child protection is reflected in the State policy implemented by central and local executive authorities, local self-government bodies, agencies, organizations and public institutions. An example of this is the implementation of the national programme “Children of Kazakhstan”, adopted by Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 1245,Footnote 14 which has now been repealed. The main areas of this programme were the prevention of crime, drug addiction, alcoholism and smoking among children.

An important step in this direction was the adoption of the Decree of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 646.Footnote 15 This Concept outlines the key areas for the development of criminal justice concerning juveniles. Particular attention is devoted to strengthening the responsibility of families, society and the State for the upbringing and development of children, as well as ensuring the observance of the rights and freedoms of minors in conflict with the law. This is achieved by improving their legal and social protection. The expected result of the implementation of the Concept is the creation of a fully fledged juvenile justice system in Kazakhstan capable of ensuring the legality, validity and effectiveness of every decision concerning juvenile offenders, as well as their re-education and social support.

Given the aforementioned, it is possible to conclude that compliance with all regulations in criminal cases involving minors is important not only from the point of view of procedural actions but also from the point of view of re-education and re-socialization of minors. In other words, criminal proceedings against minors should be educational, minimizing the negative impact on the formation of their personality. Interrogation tactics should be regarded as one of the most effective methods of obtaining full and objective testimony. The effectiveness of this method is determined by the thoughtful formulation of questions, presentation of material and written evidence, disclosure of testimony of other persons, interrogation at the scene, explanation of the consequences of the crime and persuasion of the need to cooperate with the investigation authorities. The peculiarities of the tactics of interrogation of minors require a special approach of investigators, given their special procedural position. Interrogation involves the use of various tactical techniques recommended by forensic tactics and methods of investigation of specific types of crimes. These techniques are aimed at activating memory, recalling events, detecting and exposing lies, and eliminating distortions in testimony caused by errors in perception and interpretation of events. Recommended tactics include targeted questions and presenting evidence.

When interrogating a minor, careful preparation for this process is an important factor, including familiarization of the investigator with the available data on the identity of the minor being interrogated. It should be noted that the peculiarities of studying information about a minor are in the probabilistic nature of the data obtained since the information is based on complex reasons for the person’s treatment, which cannot always be established (Karagaev Reference Karagaev2018). Consequently, if the interrogation of a minor may lead to repeated trauma to the psyche and affect health, judges refuse to satisfy requests for interrogation. Equally important is the choice of the place and environment for interrogation, which should contribute to the comfort of the interrogated person and ensure the effective conduct of the procedure. Analysing the content of Article 591 of the CPC of the Republic of Kazakhstan,Footnote 16 it is worth noting that interrogation is conducted at the place of pre-trial investigation. The person conducting the pre-trial investigation has the right, if necessary, to inspect the location where the person being interrogated is situated. In this case, the investigation is carried out by the investigator of the pre-trial investigation body under whose jurisdiction the place of commission of the criminal offence is located. As a general rule, the place of interrogation is the investigator’s office located in the relevant pre-trial investigation body.Footnote 17

For interrogation in other places, the CPC requires the consent of the person to be interrogated. First, the investigator conducting the interrogation needs a separate office. Second, it is worth compiling a plan for questioning the juvenile, indicating the data to address, the range of participants and the main questions to be asked in sequence. Third, it is highly relevant to establish psychological contact, including the creation of a favourable psychological atmosphere conducive to providing full and truthful testimony (Eshpanova Reference Eshpanova2017). Agreeing with the above, it should be noted that in conducting any investigative action involving a minor, investigators need to establish strong psychological contact and consider the personal and individual characteristics of the minor for a successful investigation and prevention of violations of their rights. Based on the above, it is possible to outline the authors’ definition of the tactics of interrogation of minors as a set of tactical techniques used by the investigator in conducting this procedural action. To achieve maximum effectiveness, this tactic requires diversity and flexibility, based on the full range of interrogation techniques. The effectiveness of interrogation is greatly enhanced if the investigator, when presenting evidence, refers to the positive qualities of the interrogated person and uses techniques to activate the juvenile’s feelings related to the offence committed or role as a witness or victim.

However, there are serious difficulties in overcoming the attitude of the interrogated, especially after they have given false testimony and become withdrawn, refusing to make contact and ignoring the significance of the evidence presented. This problem is especially relevant in the case of minors, whose psyche is not yet fully formed, and the situation requires concentration, care and maturity. At the same time, the use of “direct” arguments that directly implicate the dissemination of false information often fails to produce the desired result. It is also inadmissible to violate the requirements of the CPC when interrogating minors. To bring the interrogated person out of the state of withdrawal, it is advisable to start by discussing topics not directly related to the subject of interrogation and to show a sincere interest in the circumstances. Gradual involvement of the minor in the dialogue can be used to proceed with the interrogation questions, focusing on details that do not directly refute the false testimony, but cast doubt on some aspects of the testimony. As a rule, the investigator should not interrupt the free flow of the narrative with remarks or questions. Only if the investigator notices that the interviewee is deviating significantly from the topic, and such deviations do not contribute to the recall of relevant facts, should the interviewee be requested to stick to the topic. After the free-flowing narrative is completed, the investigator uses questions to clarify and supplement the testimony, identifying new facts not mentioned in the free-flowing narrative. This helps to verify the testimony and recall forgotten details. To consolidate the effect, the investigator may ask the juvenile to re-describe certain events, which sometimes leads to the mention of previously omitted facts (Muldagaliev Reference Muldagaliev2017).

The choice of interrogation tactics is based on an understanding of the emotional state of the interrogated person, which determines the success of the process. The beginning of the interrogation is a critical moment when the interrogated person determines their attitude towards the investigator. It is worth keeping respect for the position of a representative of the State authorities, observing ethical standards, and being polite in dealing with interrogated persons and other participants in the process. A key quality of an investigator is the ability to listen carefully to the person being questioned. An investigator using ironic smiles or defiant looks indicates a low professional level. The investigator should allow the interrogated person to speak fully without interruptions or expressions of doubt. Interruptions should only be made if there are diversions from the subject. Excessive formality, distrust or arrogance can hurt the interrogation process. The interrogator should strive for conciseness, clarity and simplicity of expression. It is undesirable to show familiarity or focus on knowledge of the criminal environment if this is not appropriate to the situation. Instead, one should strive to establish psychological contact with the interrogated person to ensure successful interrogation, depending on emotional state and preparedness. When recording the testimony of minors, tactical approaches should be used that stimulate the active thinking of the interrogated person, ensuring the full and objective recording of their testimony and the use of technical means. This may include asking controlling and clarifying questions, requests for a more precise statement of opinion, the opportunity to record testimony independently, and the opportunity to read and sign the interrogation report. Tactical methods should be flexible and consistent, forming a chain of actions with a common goal.

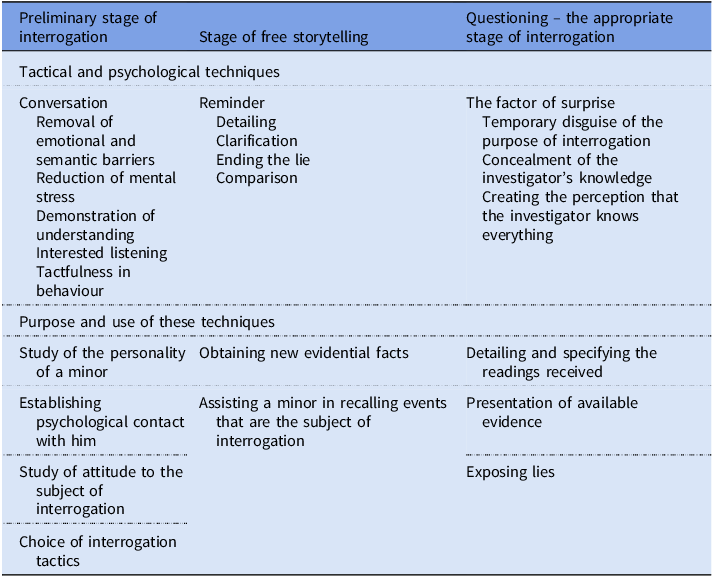

Approaches to the interrogation of juveniles are aimed at helping them to accurately recall information relevant to the resolution of the case. The investigator and the interrogated person seek to uncover the truth. It is necessary to employ tactics that account for the characteristics of a minor as a person with an unformed psyche to avoid any psychological damage (Table 1).

Table 1. Tactical features of interrogation of minors

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Consequently, the effectiveness of the interrogation of minors depends entirely on the professionalism and tactfulness of the investigator, who must competently combine various techniques to achieve the goal of establishing the truth in the case. Tactical methods during the interrogation of minors should be interrelated, logical and aimed at adequate interaction with the interrogated person, considering the peculiarities of position in the process. When using verbal tactics, investigators should observe two main principles: first, the wording should be such that it does not mislead the interrogated person or create threats or pressure (for example, blackmail, threats and other types of psychological pressure are unacceptable); second, the content of the statements should be understandable to the interrogated person, avoiding the use of legal terms or other specific vocabulary that may not be understood by an ordinary person. When using tactical techniques aimed at establishing psychological contact with the interrogated person, there is a certain scale of mistakes in building communication that can be placed between two extremes: from approaching too quickly and establishing too friendly a relationship to avoiding conversation or creating a barrier of inaccessibility, which does not meet the goals of effective communication on an equal footing.

To ensure psychological contact, the investigator should avoid meaningful statements, excessive demonstrative confidence, categorical statements without the possibility of criticism, and the desire to dominate the dialogue. Instead, a conversation should be carried out as an equal communication, without demonstrating the investigator’s knowledge and qualities. Another important aspect of the use of tactical techniques is the question of the appropriateness of remote interrogation to obtain and verify the testimony of the interrogated person. Some scholars note that remote interrogation with the use of modern technical means can be a positive innovation that does not cause additional stress to the minor and can help to quickly obtain information for the investigation without violating the rights of participants in the investigative process. The introduction of democratic changes in the new CPC of the Republic of Kazakhstan is aimed at improving the investigation process, speeding up interrogations and improving the protection of victims. However, practice shows that the use of video conferencing and technical means for interrogating minors is accompanied by practical difficulties in establishing psychological contact. New opportunities, such as interrogations via video link or from another room, are intended to overcome social barriers but may cause difficulties in establishing trust, especially in the case of interrogations of minors. For example, in the presence of parents or teachers, the investigator may become a “stranger” to the juvenile, which complicates the psychological atmosphere. However, the virtual format can ease the tension, especially if the investigator explains the benefits and purposes of such an interrogation in advance. For example, if a person is unable to attend in person for health reasons, a remote interrogation may be more comfortable for the interrogated person and facilitate more open communication.

The practical use of psychological influence during the interrogation of minors causes ambiguous reactions in terms of its legality. This is determined by the fact that the transition from psychological influence to psychological violence can occur when a person’s right to free choice of behaviour during interrogation is restricted. However, the question of whether psychological influence is violence when the investigator uses it to obtain information or reveal false testimony remains controversial. Furthermore, psychological violence is manifested when a person is deprived of the possibility of free choice of lawful behaviour following the law. In this context, the investigator should address both objective and subjective factors of psychological influence. Objective factors may include the existence of convincing evidence of the juvenile’s guilt, the apprehension of the person at the scene of the crime, and the availability of modern forensic techniques. Subjective factors, such as the mental characteristics of the person being questioned, attitude to law and order, and interaction with the investigator, are also significant. Interaction and understanding on the part of the investigator can have a significant impact on the course and outcome of the interrogation.

In the context of the interrogation of minors, particular attention is devoted to psychological impact, which plays a key role in shaping the answers of the interrogated person. Different tactics may include intellectual influence, which is aimed at providing information that may stimulate the story or the mention of additional details. Emotional impact, in turn, can evoke certain emotions, contributing to more open communication. In addition, volitional influence is also relevant, as it is aimed at manipulating the willpower of the interrogated person to achieve certain goals. An experienced investigator needs to address the individual characteristics of each juvenile being interrogated to use tactical techniques effectively. This includes analysing personality traits, understanding motivation and the ability to quickly navigate the information received. At the same time, the investigator must observe the limits of the admissibility of tactical techniques, excluding the use of violence, threats or other illegal methods to obtain testimony. These restrictions are defined by the criminal procedure legislation and are aimed at protecting the rights and legitimate interests of participants in criminal proceedings.

Thus, the tactics of interrogation of minors are conditioned by their special status in criminal proceedings, which undoubtedly affects the approach of investigators during their interrogation. State legislation explicitly prohibits the use of mental violence, especially in the context of interrogation of minors. In this regard, investigators should use tactical methods of psychological influence during interrogation, observing the legal framework. The main purpose of such an impact is to influence the internal processes of the interrogated, forming the correct position and attitude to cooperation, which contributes to better activation of their memory and improvement of the quality of information received.

Discussion

The interrogation of minors in criminal proceedings is one of the most complex and controversial topics among scholars and practitioners. Different approaches to the definition of interrogation and the methods of its conduct reflect the multifaceted nature of this problem.

Scholars continue to debate the definition of interrogation. Some, such as Hessert (Reference Hessert2021), Tenorio (Reference Tenorio2020) and Beachy (Reference Beachy2024) define interrogation as a procedural action in which the investigator obtains information from the interrogated person about the event of the crime, its participants, the nature of the damage caused, the conditions of the crime and other circumstances important for criminal proceedings. Others, such as Bettens and Warren (Reference Bettens and Warren2023) and Polito (Reference Polito2022), define interrogation as an investigative action where the participants exchange information about facts relevant to establishing the truth in a criminal case. Pollack and Weiss (Reference Pollack and Weiss2022) note that interrogation is a means of obtaining evidentiary information through the recording of testimony and verification of evidence. Addressing different points of view, interrogation can be defined as a procedure for obtaining evidential information and verifying facts. At the legislative level, the concept of interrogation as an investigative action does not have a clear definition and objectives, unlike, for example, inspection or search.

Mindthoff, Malloy, and Höhs (Reference Mindthoff, Malloy and Höhs2020) and Mindthoff and Meissner (Reference Mindthoff, Meissner, Fox and Verona2024) highlight several aspects of the importance of interrogating minors: procedural, psychological, ethical, pedagogical, educational and tactical. These aspects include compliance with legal requirements during interrogation, consideration of the psychological characteristics and temperament of the interrogated person, attention to moral aspects, individual approach and tactics adapted to the psycho-emotional state of minors (Musabaev et al. Reference Musabaev, Abenova and Zhetpisov2023). However, the criminal procedure legislation creates some contradictions regarding the right of the investigator or prosecutor to interrogate minors not only after they are recognized as suspects. On the one hand, this gives the investigator or prosecutor a certain degree of autonomy in choosing interrogation tactics. On the other hand, this may limit the rights of the juvenile suspect and representative to full protection of rights. This approach is not consistent with the scientific position of Kaplan and Cutler (Reference Kaplan and Cutler2021), who note that untimely or distorted testimony of minors may violate their right to defence.

When analysing the scientific literature on the importance of the participation of representatives of juvenile suspects in interrogation, different points of view should be highlighted. For instance, Wu, Liu, and Huang (Reference Wu, Liu and Huang2024) express a negative attitude towards the participation of unauthorized persons in interrogation, arguing that investigators can establish psychological contact and obtain truthful testimony from juvenile suspects without the help of others. At the same time, while supporting the position of Yu (Reference Yu2021), it is worth noting that the participation of those present at the further interrogation of a juvenile suspect will be effective and contribute to the establishment of the truth in criminal proceedings. The opinion of Dinata et al. (Reference Dinata and Satoto2023), who emphasize the importance of consulting a psychologist to explain the psychological aspects of the interrogation process, is also noteworthy. Consultation with a psychologist allows one to deepen the understanding of the psychological characteristics of the interrogated person, determine the best way to establish psychological contact and effectively plan the investigative action.

However, the opposite side of scholars and proceduralists, who categorically deny the need to involve legal representatives during the interrogation of minors and in criminal proceedings in general, should also be noted. Kovalenkovienė and Šemiotienė (Reference Kovalenkovienė and Šemiotienė2022) determined that summoning parents to participate in the interrogation of a juvenile defendant is inappropriate in most cases. In some cases, the accused will experience feelings of fear, shame and so on in the presence of parents, will react sensitively to the emotions of their father and mother, watch their facial expressions, movements, and smiles and give answers accordingly. This position may not be entirely valid, since the feelings of shame and guilt that a minor may experience in the presence of legal representatives (father, mother) will only help the defence counsel to establish the circumstances to be proved in criminal proceedings of this category, to verify the veracity of the testimony received, and to find out the behaviour of the minor in such circumstances.

When preparing for the interrogation of a minor, it is important to address the influence of parents on their behaviour and awareness. A minor may be subject to negative influence from their parents, which may lead to distortion of testimony. As noted by Aizpurua et al. (Reference Aizpurua, Applegate, Bolin, Vuk and Ouellette2020), parents should be invited to the interrogation only if their influence on the minor is not related to the crime committed and if the relationship with them is respectful. Therefore, the defence counsel should carefully check this information and, if necessary, obtain explanations from other relatives, friends or teachers of the minor. As for the place of interrogation, it is necessary to address tactical aspects. The place of interrogation should be chosen accounting for the convenience and effectiveness of the investigative action. As noted by Crusto (Reference Crusto2024), the choice of location depends on the specific circumstances of the investigation. Although the interrogation of minors usually takes place in the investigator’s office, sometimes it is necessary to conduct it at the place of residence. In any case, the correct choice of the place of interrogation contributes to the effective and productive conduct of investigative actions.

As noted in the previous section of the study, when interrogating minors, the investigator uses a variety of tactical techniques adapted to the characteristics of this category of interrogated persons. The choice of these techniques depends on several factors, including the characteristics of the juveniles themselves and the specifics of the interrogation situation. In this context, it is reasonable to agree with Scott (Reference Scott2023) on the necessity of employing a wide range of tactical techniques in an integrated manner rather than in isolation, allowing these techniques to interact within a systematic approach, which involves pre-evaluation and adaptation to specific situations. The use of tactical techniques during the interrogation of minors has its peculiarities and requires compliance with the law and protection of their rights and interests. The main purpose of tactical techniques is to collect and evaluate evidence. However, their use must strictly comply with the law, scientific validity and moral standards. The criteria for the admissibility of techniques are determined by the essence of the law, scientific validity and ethics. The choice of a particular technique depends on the experience of the interrogator, the situation of the interrogation and psychological state. Considering the questions posed during interrogation, Miron et al. (Reference Miron, Tolan, Gómez and Castillo2021) emphasize the importance of formulating questions that should stimulate the interrogated person to think logically and lead to obtaining the necessary testimony without prompting answers. This requires the investigator not only to prepare thoroughly for the interrogation but also to be able to adapt the questions to the psychological characteristics of each interrogated person.

Studying interrogation tactics, Boman and Gallupe (Reference Boman and Gallupe2020) emphasized that the investigator, using tactical techniques and methods of influencing the interrogated person’s psyche, records in the protocol the information necessary for subsequent identification. Notably, the working stage of interrogation can be divided into four stages. The first stage involves establishing psychological contact with the minor, which depends on the situation, the investigator’s manner of behaviour, and emotional tone, and includes the participation of third parties (teachers and psychologists). This is followed by the stages of free narration, asking questions and familiarization with the protocol and notes. The main essence of the tactical techniques used in the interrogation of minors is to influence them to obtain truthful testimony. Maloku, Jasarevic, and Maloku (Reference Maloku, Jasarevic and Maloku2021) emphasize that these techniques are based on strict adherence to the law, are aimed at obtaining reliable testimony and are not decisive, but important. To establish rapport with minors, it is necessary to be calm, responsive, compassionate and understanding. It is important to notice and resolve any tension, to engage in neutral conversations and to understand the reasons for refusing to testify (Geovani et al. Reference Geovani, Nurkhotijah, Kurniawan, Milanie and Nur Ilham2021). The free narration of minors facilitates the reproduction of information and helps the investigator to gain a more complete picture of the situation and the relationship of the interrogated person (Włodarczyk-Madejska and Ostaszewski Reference Włodarczyk-Madejska and Ostaszewski2021).

The effectiveness of an interrogation is inextricably linked to the quality of the investigator’s training and actions. A modern investigator needs to be able to systematize important information, predict situations and make decisions in the interests of law and order. The opinion of Geovani et al. (Reference Geovani, Nurkhotijah, Kurniawan, Milanie and Nur Ilham2021), supporting the importance of assessing the situation during interrogation, can be considered relevant. Assessment of the situation and tactical direction of the investigation are key aspects of the investigator’s targeted work and informed decision-making. The choice of tactical techniques for interrogation directly depends on the psychological contact and experience of the investigator, especially when involving minors. A correct assessment of the situation requires an in-depth analysis of all factors, including the state of the interrogated person and the conditions of the interrogation. The effectiveness of the use of tactical techniques is closely linked to the study of tactical risk, which covers extreme situations in the case and possible outcomes. Before making tactical decisions, the investigator carefully analyses the available information and assesses the risks.

The implementation of a system of tactical techniques is the result of the thorough preparation of investigators for interrogations. The forensic literature contains several recommendations and developed techniques and rules for preparing for investigative actions (Powers and Hayes Reference Powers and Hayes2022). These include:

-

Systematic investigation of the investigative situation, including analysis of all components of the situation, their interaction, connections, structure and functionality of the elements;

-

Forensic analysis of the crime and the object of tactical action;

-

Analysis of the events of the crime, the behaviour of its participants, the investigation process and individual investigative actions taken;

-

Forensic forecasting, including the behaviour of interrogation participants, the actions of the investigator and changes in the situation;

-

A social and biographical study of the individual;

-

Developing algorithms for investigative actions, including researching options for the development of the situation and selecting a programme of action;

-

Creating models of investigative situations in the future using the techniques of stage play;

-

Impact on the thought processes of the interrogated person;

-

Consulting on the development of interrogation situations with other investigators or specialists;

-

Analysis and filtering of publicly available or operational information about the events of the crime and its participants;

-

Use of reflection by imitating the thinking and actions of suspects;

-

Formation and analysis of possible consequences of actions.

These recommendations should be considered as the primary tasks for the investigator or judge in preparing for interrogation. The solution to these problems is closely related to the definition of a system of tactical techniques to be used during interrogation. Some of the proposed rules raise questions and require further clarification. For instance, the rule of “studying social typification” does not specify based on which methods the investigator should conduct the study. The categories of “sifting through circulating information” and “brainstorming” also need to be clarified, as their use may be controversial.

The correct use of tactical techniques to establish psychological contact allows the investigator to present evidence and convince the interrogated person of the need to give truthful testimony without degrading human dignity. The investigator seeks to determine the confusion of the interrogated person’s thoughts, encouraging cooperation. This approach fosters an emotional connection and motivates the interrogated person to give truthful testimony. There are various groups and systems of tactical techniques for establishing psychological contact in the literature, but more attention should be paid to the analysis of their effectiveness and implementation.

Conclusions

At the legislative level, there is no clear definition of the process of interrogation of minors. This leads to an ambiguous understanding of this procedure at both the practical and theoretical levels. To address this problem, the authors propose an authors’ definition of interrogation of minors as an information and psychological process carried out within the framework of criminal procedure legislation. The main purpose of this process is to obtain and record information about events which are relevant to the resolution of criminal cases and the determination of the truthfulness of testimony. This definition addresses the procedural position of minors and ensures that their rights in criminal proceedings are respected.

The purpose of interrogating minors is to obtain and record their testimony following the law, which should reflect real events and important details for the criminal investigation. The peculiarities of the tactics of interrogation of minors are determined by their status in criminal proceedings, which requires a special approach by investigators when conducting interrogations with this category of person.

Tactical methods in the interrogation of juveniles are aimed at maximizing the recall of important information necessary to reveal the truth in a criminal case. In this process, the investigator and the interrogated person cooperate to achieve a common goal – to establish the truth. The effectiveness of interrogation depends on how the investigator skilfully applies tactical techniques, accounting for the peculiarities of the psychology of a minor who does not yet have fully formed thinking and may react inadequately to certain situations. The success of the interrogation is directly related to the professionalism and sensitivity of the investigator, who correctly combines various tactical methods. All techniques should be logical, interconnected and aimed at revealing the truth.

The choice and use of tactical techniques during interrogation are closely related to the unique aspects of forming psychological contact in specific situations of investigative (or judicial) actions, especially when it comes to interrogating minors. Assessing such a situation requires a high level of professionalism and experience on the part of the investigator (or judge), including a careful analysis of all criminal proceedings, as well as consideration of the role and position of each participant, including the interrogated person, analysis of the current conditions of the interrogation and consideration of all positive and negative factors affecting the process and its results.

The recommendations arising from the study of interrogation tactics in crimes committed by juveniles are based on the identified peculiarities of legal regulation and the results obtained. It is necessary to strengthen the training of investigators and judges in the field of juvenile psychology, methods of establishing psychological contact and interrogation tactics, addressing their specific characteristics. More detailed interrogation techniques should be developed, including algorithms for establishing contact, asking questions, and analysing testimony, addressing the age and psychological characteristics of the interrogated. Further research could focus on the psychological mechanisms of interaction between the investigator and the juvenile, including an analysis of the impact of the emotional state, and verbal and non-verbal communication on the results of the interrogation. It is equally important to develop standards and recommendations on interrogation tactics for minors to ensure a unified approach and respect for the rights and interests of the interrogated.

Limitations of the study may include limited access to real interrogation situations, possible distortions in the testimony of interrogated persons due to their psychological state, and restrictions on the use of certain methods due to ethical and legal constraints. The results of the study may depend on other external factors, such as changes in legislation or the socio-cultural environment.

Competing interests

No potential competing interests were reported by the authors.

Nurlan Apakhayev, PhD, is a Professor at the Department of Law, Q University, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan. His research interests include legal theory, criminal law and the development of national legal systems.

Zhanna Sadykanova, PhD, is an Associate Professor and Head of the Department of Jurisprudence, Sarsen Amanzholov East Kazakhstan University, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Republic of Kazakhstan. Her research focuses on constitutional law, legal education and human rights protection.

Gulmira Bairkenova, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the Department of Jurisprudence, Sarsen Amanzholov East Kazakhstan University, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Republic of Kazakhstan and is a candidate of legal sciences. Her academic interests include civil law, legal regulation of property relations and legal culture.

Indira Smailova, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the Department of Jurisprudence, Sarsen Amanzholov East Kazakhstan University, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Republic of Kazakhstan and is a candidate of legal sciences. Her research areas include administrative law, public governance and legal aspects of public administration.

Ainur Ramazanova, PhD, is an Associate Professor at the Department of Jurisprudence, Sarsen Amanzholov East Kazakhstan University, Ust-Kamenogorsk, Republic of Kazakhstan and is a candidate of legal sciences. Her work focuses on environmental law, legal policy and sustainable development legislation.