Introduction

Hand hygiene is a fundamental component of standard precautions in healthcare settings, helping to prevent the transmission of pathogens and healthcare-associated infections. 1 In neonatal intensive care units (NICU), where patients are particularly susceptible to healthcare-associated infections due to their immature immune system, high adherence to hand hygiene is essential. Despite the strong evidence of hand hygiene effectiveness, adherence was reported to be inadequate in NICUs. Reference Pasricha, Singh, Pasricha, Jimal and Khurshid2–Reference Erasmus, Daha and Brug5 For example, Lambe et al. reported an average adherence rate of 67% in 12 NICUs. Reference Lambe, Lydon and Madden4 Hand hygiene adherence in the neonatology department of the University Hospital Zurich (USZ) was also found to be improvable. Like other neonatology wards, the USZ neonatology has experienced outbreaks of pathogenic bacteria. Reference Wolfensberger, Schmid and Sax6–Reference Hosoglu, Hascuhadar, Yasar, Uslu and Aldudak8 Over the past years, inspired by the World Health Organization’s (WHO) multimodal hand hygiene improvement strategy, several interventions to increase hand hygiene adherence have been implemented. 1 Despite significant resource investment, hand hygiene adherence still had room for improvement, healthcare practitioners (HCP) were repetitively observed to be unfamiliar with hand hygiene indications and technique, and the transmission of pathogens continued.

Hand hygiene adherence as per WHO indications and rubbing technique are driven by the individual behavior of HCP. Several theories, models and frameworks aim to help explain individual behaviors. Two of these models are the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behavior model (COM-B), Reference Michie, van Stralen and West9 and the more granular Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Reference Michie, Johnston and Abraham10,Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie11 Understanding the drivers and influences of individual behavior can inform the development of interventions specifically tailored to address identified barriers and facilitators. Reference Baker, Camosso-Stefinovic and Gillies12 The Behavior Change Wheel with the COM-B model as its central component can guide and facilitate tailoring interventions.

While work has been done to investigate the drivers of individual behavior on hand hygiene in adult ICUs, little is known on such determinants in neonatal settings. Reference Nyantakyi, Caci and Castro13 Patient populations, though, are considerably different between NICU and adult ICU settings, which could affect risk perception. Settings vary in terms of equipment (e.g. incubators) and ongoing presence of family members. A study found that nurses in NICU (in comparison to adult ICU) spent more time physically caring for patients, but less time using monitors and devices. Reference Douglas, Cartmill and Brown14 Frequent alarms occur as patients often experience apnea and hypotonia/bradycardia episodes, requiring physical stimulation to stabilize them. Reference van Zanten, Tan and Thio15 These factors affect hand hygiene indications and likely influence the underlying determinants of hand hygiene adherence. This study therefore seeks to describe the specific drivers of hand hygiene behavior in the NICU with the aim to inform the development of tailored hand hygiene interventions in this setting.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in November 2022 in the Department of Neonatology of the USZ, Switzerland. The department has both a NICU and an intermediate care unit with a total of 32 places. The work force includes 113 nurses, 26 physicians, and four members of other professional groups (e.g., physiotherapists, and music therapists). The local neonatology infection prevention and control (IPC) team is supported by the hospital IPC team.

Hand hygiene indications, technique, monitoring, and past interventions

The USZ neonatology ward follows the institutional concept of the “four moments for hand hygiene,” which is an adapted version of the “WHO my five moments for hand hygiene” 1 (Appendix 1). Specific to the neonatology setting, HCPs disinfect the forearms in addition to hands before and after contact with the patient. Hand disinfectant is provided by mounted dispensers (a minimum of one dispenser at every patient’s bedside, entrance, sink, dressing and intubation trolley, and ward round trolley), and wearable pocket dispensers. Hand hygiene is monitored through unannounced observations and monitoring of hand disinfectant consumption.

During the time of the interviews and in the preceding years, a number of interventions were carried out with the aim to improve hand hygiene adherence. These included, e.g., educational sessions in various forms, the use of a UV-Box with fluorescent hand disinfectant to train hand hygiene technique, institutionalization of peer feedback, and observation and feedback from hospital IPC experts and local IPC team.

Theoretical frameworks

We used the TDF with 14 theoretical domains, and the COM-B model with its higher-level structure as theory-based guiding frameworks for this study. For a detailed description of the two frameworks and their components, please refer to Appendix 2.

Study participants and data collection

All frontline HCP employed on the neonatology ward and all IPC experts (including the local neonatology IPC team and the hospital IPC experts responsible for the neonatology unit) were invited to participate in the study as interviewees. The HCPs were purposefully selected to ensure a representation of different professional groups, ages, genders, and years of work experience, ensuring a broad experience and knowledge. Interview participation was voluntary. The interviewees were informed about the reason for data collection (i.e., the planned tailoring of implementation strategies to increase hand hygiene adherence) and de-identification of collected data before analysis. Written informed consent from interviewees was obtained.

The interview guide of the semi-structured interviews was developed based on the TDF, pilot tested and refined based on feedback to ensure comprehension and coherence (see Appendix 3 for questionnaire). The IPC experts were asked to take a third-person perspective and report on the probable influences of hand hygiene adherence of the frontline staff.

Interviews took place on the neonatology ward and were conducted by a master medical student (TB), who was neither part of the department of neonatology, nor the hospital IPC team, and who received an in-depth training before conducting the first interview. The interviewer kept the discussion focused to the target behavior (i.e., hand hygiene adherence to indications and technique) and was committed to maintain an atmosphere of mutual trust and respect throughout the conversation. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Two researchers (TB, AW) conducted coding independently. The researchers maintained a high level of reflexivity throughout the data analysis process, Reference Patton16 continuously reflecting on their own perspectives to ensure the integrity and credibility of the findings. Coded segments were compared, and, in case of disagreement, consensus was reached by discussion, or by consultation of a third researcher (LC).

The interview transcripts were first coded deductively by assigning relevant segments to the 14 TDF domains (with two separate domains “intentions” and “goals” merged to one domain “intentions and goals”) and identifying each as either a barrier or a facilitator. At the TDF level, the frequency of codes was calculated both for barriers and facilitators and compared between professional groups using a two-sample test of proportions.

Then, an inductive thematic analysis was conducted to capture nuances in the data and build more granular and context-specific categories. Finally, determinant themes (hereafter: determinants) were created across TDF domains, but within COM-B domains. “High priority” determinants were defined as factors whose addressing as barriers or leveraging as facilitators was likely to improve hand hygiene adherence in a quality improvement intervention in the current setting, in comparison to non-priority determinants which did not require modification. Last, relationships between determinants were described based on interview segments that showed positive or negative influences among them.

No specific coding software was used but the commentary function of Microsoft Word and Microsoft Excel to organize the coded segments. Statistical analyses were conducted with Stata 16.1 17 .

Ethics

This context analysis was part of a quality improvement project, and formal ethical evaluation was waived by the Cantonal Ethics Commission (Req-2022-01325).

Results

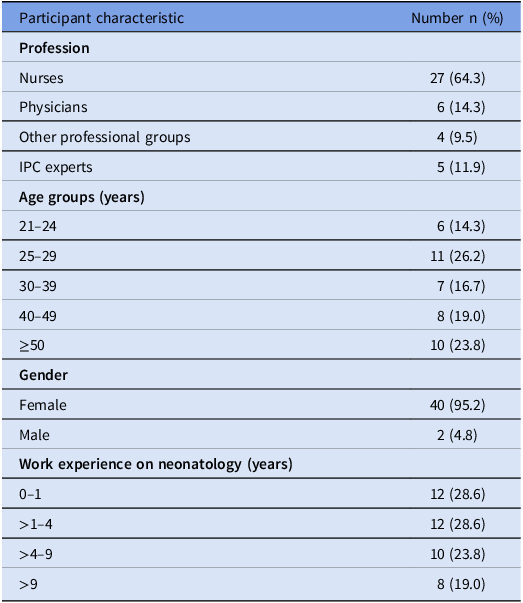

A total of 42 interviews were conducted, 27 (64%) with nurses, six (14%) with physicians, four (10%) with other professions, and five (12%) with IPC experts. Table 1 informs about the demographics of the interview participants. Median duration of the interviews was 21min (IQR 17 min–29 min).

Table 1. Summarizing the characteristics of the interview participants

Abbreviations: IPC, Infection Prevention and Control.

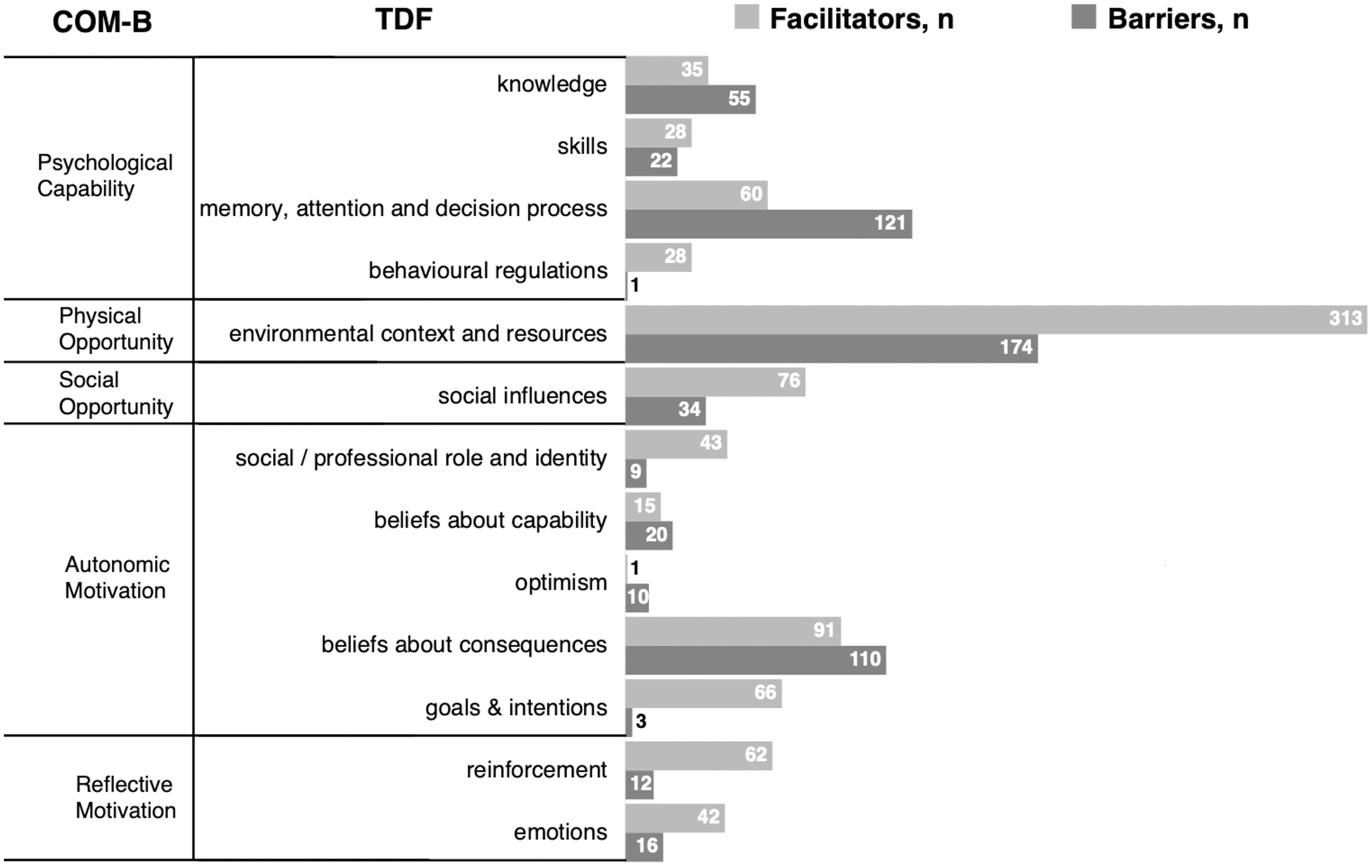

TDF barriers and facilitators

A total of 1173 interview segments were coded and 1447 TDF codes were assigned, with 860 (59%) identified as facilitators, and 587 (41%) as barriers. The TDF domains most commonly coded as facilitators were “environmental context and resources,” “beliefs about consequences,” and “social influences.” Together, they represented more than half of the facilitators. The TDF domains most coded as barriers were “environmental context and resources,” “memory, attention and decision process” and “beliefs about consequences.” Together, they represented two-thirds of all barriers (Figure 1 and Appendix 4). Two of the three most mentioned determinants were consistent across the four professional groups, but IPC experts less often mentioned “beliefs about consequences” than the three other groups (each P < 0.01) (Appendix 5).

Figure 1. Frequency of barriers and facilitators according to the TDF and mapped to the COM-B model. Number of interview segments assigned to the specific domains of the TDF Reference Michie, Johnston and Abraham10,Reference Cane, O’Connor and Michie11 and COM-B, Reference Michie, van Stralen and West9 grouped in barriers and facilitators. Abbreviations: “COM-B”, Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behavior model; “TDF”, Theoretical domains framework.

Determinants of hand hygiene adherence

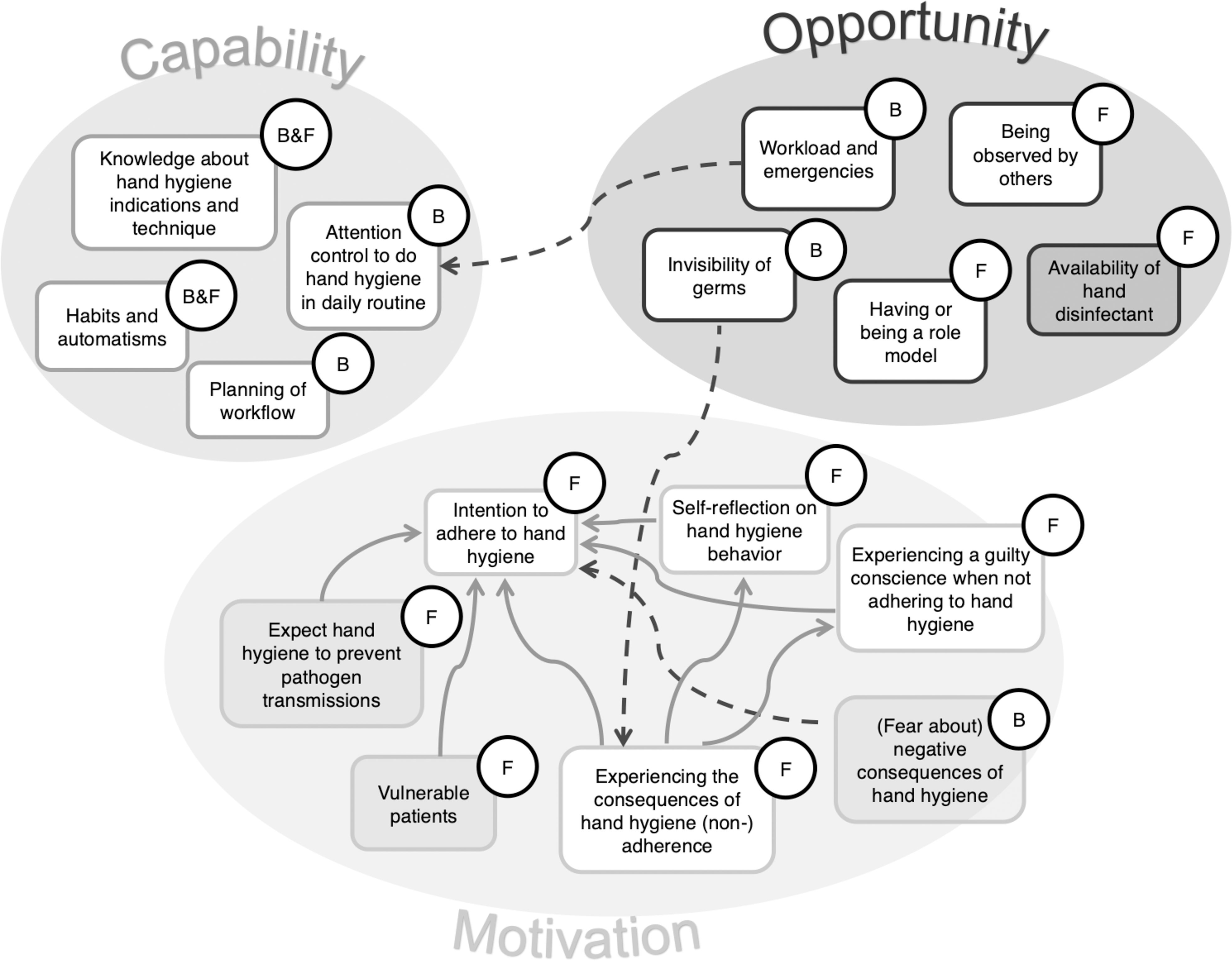

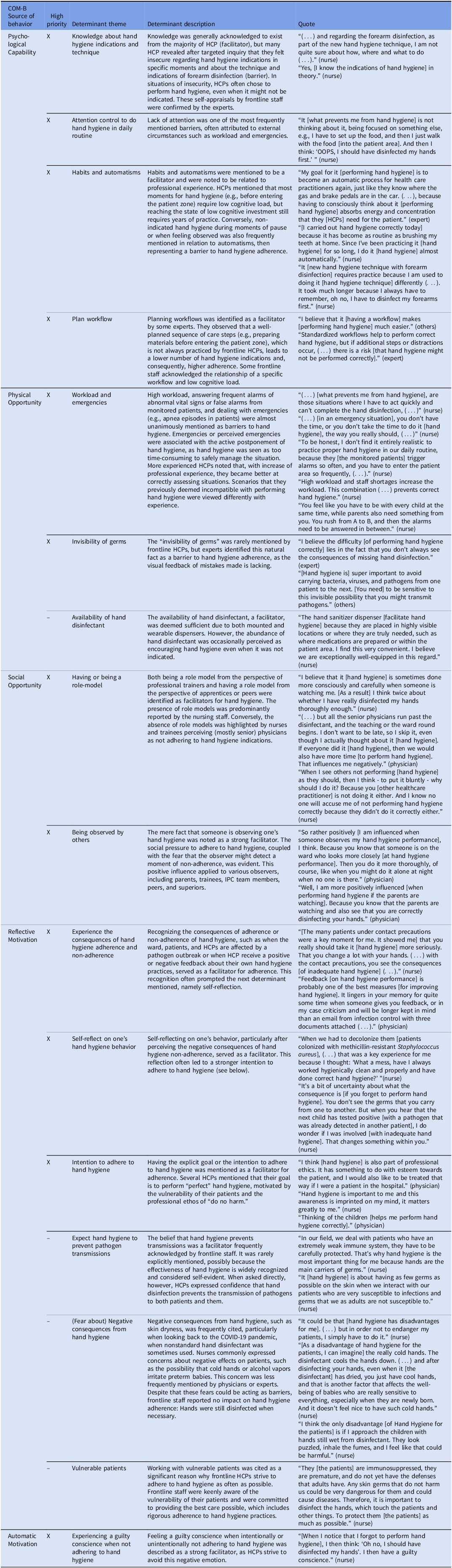

Inductive thematic analysis led to identification of 16 determinants, twelve of which were deemed high priority, and four non-priority. Figure 2 visually summarizes the high-priority and non-priority determinants, the connections between them, and if they were mentioned mainly as facilitator, barrier, or both. Table 2 gives an in-depth overview and description, including illustrative quotes of interviewees.

Figure 2. Determinants for hand hygiene adherence grouped by COM-B domains. All determinants are depicted in boxes with either white or gray background, grouped according to the three COM-B domains. Determinants in boxes with white background are high-priority, those with gray background are non-priority. The letters B and F indicate if the determinant was mostly mentioned to be present as a barrier (B) or a facilitator (F) for adherence. If Barriers and Facilitators both were mentioned equally, they were referred to as B&F. Solid arrows indicate positive interference, dashed arrows indicate negative interference between determinants. Abbreviations: “B”, barrier; “COM-B”, Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behavior model; “F”, facilitator.

Table 2. Summarizing the determinants themes (third column) identified in this study, mapped to the six COM-B domains (first column) and rated regarding priority (second column, X = high-priority). The fourth column describes the determinants in more detail, the fifth column provides some informative quotes from the interviews

Abbreviations: COM-B, Capability, Opportunity, Motivation and Behavior model; HCP, healthcare practitioner; IPC, Infection prevention and control.

Four determinants were found in “psychological Capability,” all of them considered high-priority: “knowledge about indications and technique” of hand hygiene and “habits and automatisms” were mentioned as being present as both facilitator and barrier. The lack of “attention control to perform hand hygiene in daily routine” and “planning of workflows” were described as barriers.

Three determinants were assigned to “physical Opportunity.” “Workload and emergencies” and the inherent “invisibility of germs” were considered high-priority and were mentioned as barriers. The “availability of hand disinfectant” was classified as a non-priority facilitator as hand disinfectant is sufficiently available in the USZ. Two determinants assigned to the “social Opportunity” source, namely “role-models” and “being observed by others,” were deemed high-priority facilitators.

Six determinants were assigned to “reflective Motivation” and three thereof were high-priority facilitators: The “intention to adhere to hand hygiene,” was central, with “perceiving the consequences of (non-)adherence,” and “self-reflect on one’s hand hygiene behavior” that influence adherence via this determinant. “Expect hand hygiene to prevent transmissions” was considered a non-priority facilitator as it was deemed so obvious that no further addressing was necessary. The same was true for caring for “vulnerable patients,” a strong facilitator for adherence. The barrier “negative consequences from hand hygiene,” like dryness of hands, has improved after return to the usual hand hygiene product that was temporarily replaced during the COVID-19 pandemic and thus deemed non-priority. The only high-priority facilitator that was assigned to “automatic Motivation” was “having a bad conscience” when not adhering to hand hygiene.

Discussion

In this paper, we report the findings of an in-depth and theory-based analysis of the behavioral determinants of hand hygiene adherence in neonatology. With this qualitative study, which allows a deeper understanding of HCP perceptions and drivers compared to quantitative methods, we identified 16 determinants. Twelve were considered of high priority to increase hand hygiene adherence in our setting. Four high-priority determinants were identified in each of the COM-B domains “psychological Capability,” “environmental and social Opportunity,” and “reflective and automatic Motivation.” While themes from “Capability” and “Opportunity” were both facilitators and barriers, high-priority “motivational” determinants exclusively were facilitators.

Several other study groups have investigated drivers for (non-)adherence in hand hygiene, some in neonatology, Reference Pasricha, Singh, Pasricha, Jimal and Khurshid2,Reference Pessoa-Silva, Pfister, Touveneau, Perneger and Pittet18 but the majority in non-neonatal settings. Similar to the present study, most investigations identified a range of barriers and facilitators rather than just one or a few. Reference Boscart, Fernie, Lee and Jaglal19,Reference Yehouenou, Abedinzadeh and Houngnihin20 Fuller et al., who investigated reasons for hand hygiene non-adherence on ICUs and acute care units by interrogating HCP immediately after hand hygiene observation, identified “memory/attention/decision making” and “knowledge” as the main determinants for hand hygiene noncompliance. Reference Fuller, Besser, Savage, McAteer, Stone and Michie21 Similarly, Pasricha et al. who assessed barriers through questionnaire and thus with a greater distance from the action, identified “forgetfulness,” “lack of awareness,” and “lack of knowledge.” Reference Pasricha, Singh, Pasricha, Jimal and Khurshid2 Such determinants categorized under the COM-B “Capability” domain, are per definition intrinsic to HCPs, and were confirmed by several other authors. Reference Dyson, Jackson and Cheater22–Reference Le, Lehman, Nguyen and Craig25 While our interviewees also mentioned some of these as barriers (i.e., “lack of attention control” or “planning of workflows”), initially they expressed confidence in their knowledge and ability to perform hand hygiene. However, upon further questioning, some acknowledged knowledge gaps. On the contrary, the IPC experts, who were conducting hand hygiene interventions and adherence observations in the past, mentioned “knowledge” as one of the most common barriers in frontline staff. This could be attributed to individuals either not recognizing their own knowledge gaps or feeling hesitant to admit them in an interview situation. While “knowledge,” “attention control,” “planning of workflow” sure all are important for hand hygiene adherence, they all require active investment of HCP. Ideally, hand hygiene is performed automatically as a habitual behavior. As such, hand hygiene habits developed through years of work experience were often cited as facilitators.

The most frequently mentioned determinants in our study were those lying outside of the HCP’s perceived own influence, in the COM-B “Opportunity” domain. The high workload and patient emergency situations were often cited as barriers. This appears to be a common hindering factor in various hospital settings worldwide, Reference Pasricha, Singh, Pasricha, Jimal and Khurshid2,Reference Song, Stockwell, Floyd, Short and Singh3,Reference Dyson, Jackson and Cheater22,Reference Deshommes, Nagel and Tucker26–Reference Lambe, Lydon and Madden28 likely linked to the high cognitive load, distraction, and competing priorities such situations bring along. On the other hand, the “availability of hand disinfectant” was perceived to be sufficiently present in our setting and thus was seen as non-priority determinant. In other hospitals, both in resource-limited countries, where there might be fewer hand disinfectant dispensers, and in higher resource settings, where dispensers were e.g., reported to be empty, non-availability of hand disinfectant was identified as one of the most relevant barriers. Reference Deshommes, Nagel and Tucker26,Reference Bezerra, Valim and Bortolini29–Reference Vaughan-Malloy and Sandora31 In our neonatal setting, social influences, such as “having role models” or “being observed by others,” particularly parents, were important facilitators. This was also shown in an interview study with HCPs from ICUs that describes the sense of “being watched” and “reminders and encouragement from peers” to improve adherence, Reference Lambe, Lydon and Madden28 and a questionnaire study that found that the “opinion of important others” influences hand hygiene behavior. Reference Pessoa-Silva, Pfister, Touveneau, Perneger and Pittet18 These findings encourage the use of peer feedback and the fostering of a speak-up culture.

While our study identified several determinants in the COM-B “reflective and automatic Motivation” domain, such determinants were only rarely reported by other authors. Reference Lambe, Lydon and Madden28,Reference Squires, Linklater and Grimshaw32 We hypothesize that the relevance of the motivational determinants is linked to the neonatal setting where patients are highly vulnerable and dependent, and the frontline staff feel a particularly high obligation to protect them from adverse events. Additionally, in neonatology, pathogen transmission events are frequently detected due to high microbiological screening activity. The determinants we identified in the “motivational” domain included active cognitive processes and reflections that – similar to the behavioral model of the “theory of planned behavior” Reference Ajzen33 – all ultimately influenced the “intention or goal to adhere” to hand hygiene. Most motivational determinants were positive influencers, leading to an increase of the “intention to do hand hygiene.” However, how much the “intention to perform hand hygiene” predicts actual hand hygiene adherence is unclear, and was questioned by O’Boyle et al., who postulated that hand hygiene behavior may be more sensitive to external factors than to internal motivational factors. Reference O’Boyle, Henly and Larson34

As several other study groups, we perceived the use of the TDF to guide our analysis as useful. Reference Yehouenou, Abedinzadeh and Houngnihin20,Reference Fuller, Besser, Savage, McAteer, Stone and Michie21 Assigning the determinant themes also to the COM-B model will later facilitate the tailoring of implementation strategies using the Behavior Change Wheel, a comprehensive framework that guides the design of behavior change interventions. In the process of introducing behavior change, prioritization of determinants – i.e., identifying important determinants – is one of the crucial steps to be carried out. In our setting, four determinants were indeed found but their addressing was perceived not necessary, either because the concepts or circumstances were well understood, obvious, or had already been addressed in the past. While “importance” is one prioritization criterion, “changeability” – the ease or difficulty of changing a factor – could be another. Reference Green, Gielen, Peterson, Kreuter and Ottoson35 Highly changeable determinants, often termed as low-hanging fruits, could be initially targeted in behavior change interventions, especially when they are also considered important. Notably, not only the determinants themselves but also their classification based on importance and changeability can vary across settings, based upon specific contexts and priorities.

While this study has several strengths such as the theory-based approach, that facilitated comparison of our results with other papers, and the cumulative 16 hours of interviews with purposefully selected HCP, it also has some limitations. First, as in all interview studies, a social desirability bias cannot be excluded. Interviewees might have answered the questions in a way they believed to be more acceptable or favorable rather than expressing their true thoughts and behaviors. To mitigate this potential bias, we selected an interviewer who was not part of the IPC or the neonatology team, and who made efforts to create an atmosphere of openness and trust. We also included IPC experts as interview partners, who, based on their experience and close contact with frontline HCP, were able to provide a likely more objective perspective on the frontline staff’s hand hygiene behavior. Second, there is a risk of selection bias, as the interviews were conducted on a voluntary basis and employees with a positive attitude towards hand hygiene might have been more likely to participate. Third, the interviews were conducted in German, which might have led to employees with German as a second language being less likely to participate, potentially leading to reduced diversity of interviewees. Lastly, this was a single-center study conducted in a high-resource setting, and the findings may thus not be transferable to all other settings.

In conclusion, this qualitative interview study identified several determinants influencing hand hygiene adherence in a neonatology setting. Some are well-known, lying inside an individual HCP such as knowledge about indications or automatisms, or outside of HCP such as high workload and being watched by others. Others are new and likely particularly specific for the neonatal setting, such as the motivational determinants of self-reflection on hand hygiene behavior or the very strong intention to adhere to hand hygiene. Our findings can now inform hand hygiene interventions that are tailored to the needs of HCPs in the neonatology wards, optimizing the use of time and personnel resources. A study comparing the determinants of hand hygiene adherence in both adult ICUs and NICUs is needed to confirm and further elucidate the hypothesized differences between these settings.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2025.82

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all healthcare professionals and infection prevention and control experts who participated in this study for their collaboration, time, and trust.

Author contributions

TB and AW designed the study and created the interview guide. TB acquired the data. TB, AW, and LC analyzed and interpreted the qualitative data. TB and AW drafted the manuscript, and CW, JF, LC, MTM, WZ, and YS provided critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors agree with the content and conclusions of this manuscript.

Financial support

No funding was provided for this study.

Competing interests

None to declare for all authors.