To the Editor—The world at large lacks disaster readiness. The history of humanity includes narratives of how we have faced and overcome challenges and difficulties, both natural and human made, both large and small.Reference Ricciardi, Palmer and Yan1,Reference Adger, Hughes, Folke, Carpenter and Rockström2 In parallel to a racial pandemic,Reference Su, McDonnell and Ahmad3 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has also been linked to social inequality in its many forms and is another test of humanity’s resolve.4 Despite the depth of knowledge and experience with challenges that humanity has accumulated over time, the showcase of incompetence in response to COVID-19 is profoundly concerning.Reference Renda and Castro5 From the chronic and consistent shortage of medical supplies to the moral crossroad of deciding who should be given a ventilator,Reference White and Lo6 the lack of disaster readiness has effectively caused health organizations and government agencies to regress into institutions of despair.

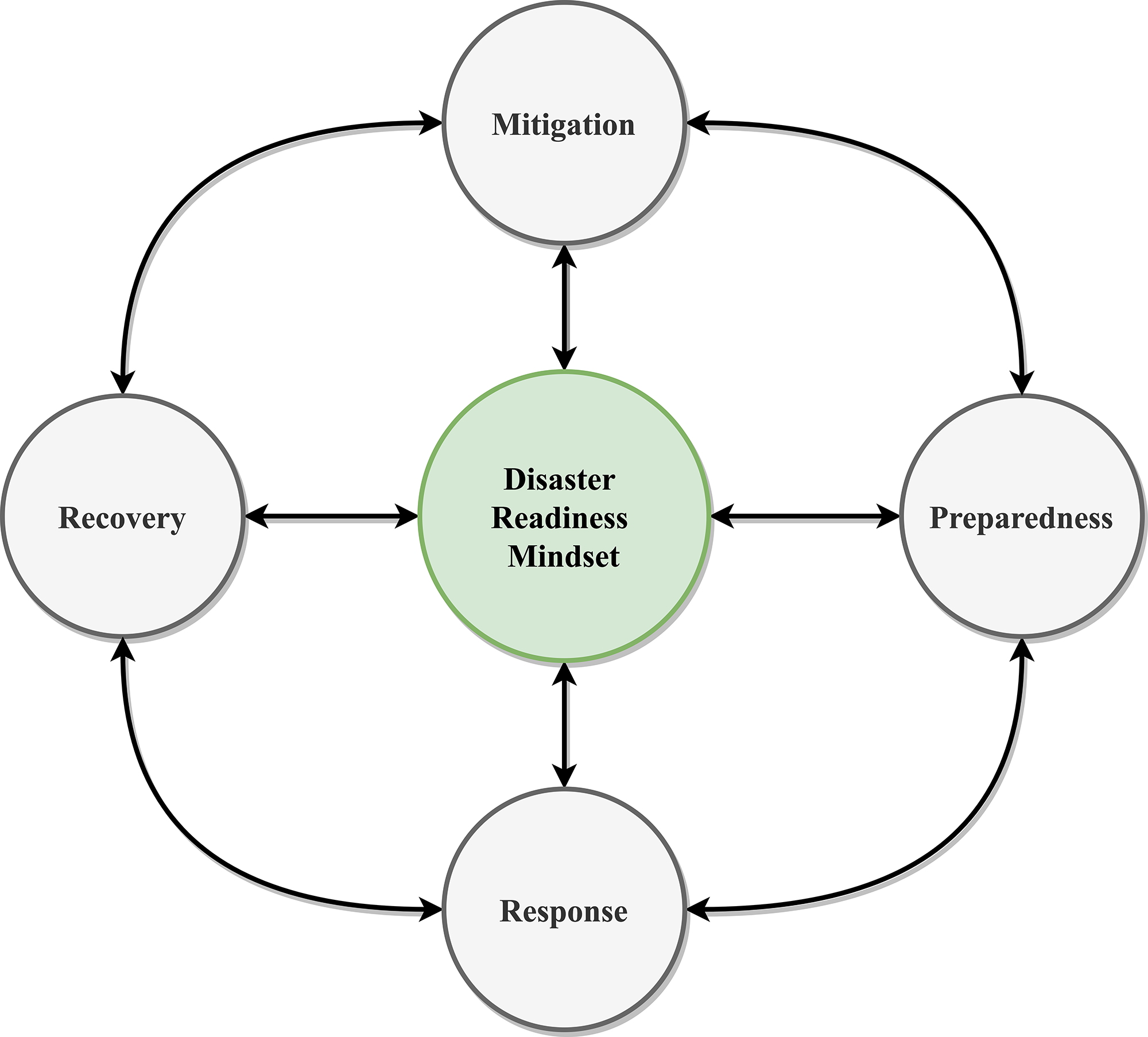

Worldwide, the lack of adequate response and emergency management in governments amid COVID-19 has upended the lives and livelihoods of individuals, has all but destroyed gross domestic products (GDPs), and has created avoidable vulnerabilities and ‘ground zeroes’ across continents.Reference Renda and Castro5 Despite the bleak situation, incompetence in the face of any disaster is not a permanent trait; instead, a more transient position improves with preemptive thinking and well-thought disaster preparation, such as a disaster readiness mindset. Disaster readiness is a state in which individuals or governments have both the plan, resources, and psychological prowess needed to mitigate or offset the potential adverse effects of disasters. This mindset involves the foresight and capability to effectively mitigate, prepare, respond, and recover amid and beyond disasters promptly (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. A schematic model of disaster readiness mindset.

Overall, a disaster readiness mindset is a preemptive, proactive, and people-centered philosophy that individuals and organizations need to ensure survival during and thriving after disaster outbreaks with tamed fear and uncertainty. A disaster readiness mindset may also be what is needed for organizations to mitigate effectively, prepare for, respond to, and recover from potential adverse impacts of disasters. It has the potential to help key stakeholders take into consideration most, if not all, of the factors that determine how disasters disappear in news feeds and appear in textbooks. With a disaster readiness mindset, insights from preemptive efforts and numerous disaster mitigation solutions in place, disasters can be more easily predicted, predicted, and controlled.

Ultimately, the disaster readiness mindset entails the following: (1) the foresight to develop a comprehensive disaster readiness plan that can help individuals and governments better cope with disasters cost-effectively; (2) the ability to locate and secure critical resources before a disaster that are needed for the society to survive and possibly thrive despite the adverse effects of the potentially catastrophic events; and (3) the agility, mobility, and flexibility required to execute the plan and deliver optimal results in an evolving situation. Finland, for instance, owing partly to the country’s ingrained awe towards its extensively bordered neighbor, arguably has the world’s most well-prepared and resource-abundant bunker systems.Reference Grove7 In the event of urgent disasters, these bunkers can host all of Finland’s population and protect its people from natural or human-made disasters. The bunkers are 18 m underground, span >124 miles, and can facilitate population-wide contamination mitigation procedures (eg, showers in the event of a chemical attack). They are equipped with food, bedding, medical facilities and supplies, and a wide selection of evening entertainment.Reference Grove7 In the wake of COVID-19, by repurposing resources, Finland is among the few countries reportedly unaffected by a shortage of medical supplies due to its disaster readiness mindset.Reference Anderson and Libell8

The example of Finland shows that disaster readiness mindset can give a government the ability to identify antecedents to potential disasters, detail the potential risks a disaster might engender, and correspond with proactive strategies that either offset or minimize those risks. Disasters are a fact of life that can be prepared for but not avoided. Health organizations and government agencies across the world must develop a disaster readiness mindset so that even though COVID-19 is mutatingReference Grubaugh, Hanage and Rasmussen9 and the looming possibility of future pandemics is constant,Reference Honigsbaum10 the damage of these disasters can become better predicted, prevented, and controlled.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and reviewers for their constructive input.

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.