How should one write, what words should one select, what forms and structures and organization, if one is pursuing understanding? (Which is to say, if one is, in that sense, a philosopher?) Sometimes this is taken to be a trivial and uninteresting question. I shall claim that it is not. Style itself makes its claims, expresses its own sense of what matters. Literary form is not separable from philosophical content, but is, itself, a part of content—an integral part, then, of the search for and the statement of truth.

(Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum1992, 3)The impersonal tradition in philosophy

This is a paper about philosophical methodology. In particular, it is about the ways in which we analytic philosophers write—and don’t write—about ourselves. I’ll start with a story. A few summers back, I was working as a teaching fellow for a philosophy course. When the time came for students to write final papers, most students answered a standard prompt, but one petitioned to write about a topic of her own: cochlear implants. When physicians decide whether or not to perform surgery, normally they rely on the informed consent of the (potential) patient. Cochlear implants, however, work best when implanted in young children—children too young to decide for themselves. So who should choose? In class, we had read an article that proposed a simple response: physicians should defer to parents, and parents, in turn, should always opt for the surgery. My student wanted to push back. She agreed that cochlear implant surgery had benefits, she said, but she also thought it had costs—costs that the article failed to adequately appreciate. I agreed to let her write on her own prompt on the condition that she come to office hours regularly to discuss her progress. We had been working together for almost a week before I thought to ask how she had gotten interested in the topic. I had not bothered to ask sooner because I assumed, in a vague way, that I already knew the answer: she picked the topic because she thought she could say something clever enough to get an A. But instead, she blinked and said, “Well, because I’m Deaf.”

She tucked her hair behind her ear to reveal a hearing aid that I had failed to notice. I was thrown. The two of us had been talking about Deafness for days—workshopping outlines, dissecting drafts—yet her personal connection to the topic had never once come up.

Once she got started, she spoke about her experiences eloquently. Easily. She explained that she had been born with partial hearing loss, and although she herself had never been a candidate for cochlear implants, she identified with those who were. Throughout her childhood and teenage years, she had spent a great deal of time thinking about the liminality of being part Deaf. She said it felt like standing on the border of the Deaf community, one foot in and one foot out. As she told her story, I felt more forcefully the claims that she had been trying to make in her paper. More than that: I understood the claims more clearly. The argument she had been trying to make finally clicked into place.

I asked if she wanted to write a bit about herself in her paper, to use her personal experiences as a kind of philosophical evidence. She thought for a long time before answering, “I didn’t know we were allowed to do that.”

My fellow teachers and I had not intended to ban personal writing. To be honest, we had not given the matter any thought. But my student, I realized, had drawn a perfectly reasonable inference. Like any good student, she was imitating the professional papers we had been reading in the course—and those papers contained nothing like the kind of writing I proposed.

As analytic philosophers, in one sense, we write about ourselves all the time: we use first-personal pronouns like “I” and “me” and “us” and “we” liberally. In her survey of 50 recently published philosophy papers, rhetoric scholar Helen Sword found that 92% used first-personal pronouns (Sword Reference Sword2012, 16). In my own survey of 46 papers, I found that 100% used them.Footnote 1 Whatever the exact number is, it is very high.

In another, deeper sense, however, philosophy papers tend to be reticent about the personal. The way we write about ourselves tends to be quite thin. The typical paper is grammatically first-personal, so to speak, but not substantively first-personal. In his classic “Guidelines on writing a philosophy paper,” Jim Pryor tells students: “You may use the word ‘I’ freely, especially to tell the reader what you’re up to (e.g., ‘I’ve just explained why… Now I’m going to consider an argument that…’)” (Pryor Reference Pryor2012). And that is precisely how professional philosophers tend to write. Consider this passage from Julian Savulescu’s “Genetic interventions and the ethics of enhancement of human beings,” a typical representative of the papers that my students and I had been reading that summer. (I am concerned not with what Savulescu writes: my interest is how he writes.)

Should we use science and medical technology not just to prevent or treat disease, but to intervene at the most basic biological levels to improve biology and enhance people’s lives? By “enhance,” I mean help them live a longer and/or better life than normal … In this paper I will take a … provocative position. I want to argue that, far from being merely permissible, we have a moral obligation or moral reason to enhance ourselves and our children. (Savulescu Reference Savulescu and Steinbock2009, 417)

In this passage and throughout the paper, Savulescu uses the first-personal “I” for Pryor-style signposting: “In this paper, I [take such-and-such position].” “By [technical term], I mean [definition].” And he uses the plural “we” to make universal moral claims: “We have a moral obligation or moral reason to [do so-and-so].” But what about the particularities of Savulescu’s own life? How did he arrive at his view? Has he gotten biomedical enhancements himself? Has he gotten them for his children? Does he have children? On such questions he remains silent. Despite all the first-personal pronouns, the writing reveals little about the life of its author.

As Annette Baier observes, “The impersonal style has become a nearly sacred tradition in moral philosophy” (Baier Reference Baier1995, 194; see also Brison Reference Brison2002, 28).Footnote 2 (No wonder my student thought she was “not allowed” to write about herself!) Strictly speaking, the impersonal tradition does not deny that the scholar has a particular body or a particular history or a particular social position. That would be absurd. Instead, it denies such particularities have any legitimate relevance to the scholar’s work. Philosophical writing occasionally contains what I will call incidentally personal elements—elements that involve particularities of the scholar’s life, but not in a way that makes any meaningful difference to the argument. Such incidentally personal elements can be compatible with impersonal tradition. Here’s a simple example. In a paper on risk, Johanna Thoma presents the following case:

Take my choice of whether to cycle to work or take the train. Cycling always takes about the same amount of time, and I can be certain that I will make my first appointment on time. The train is less reliable, such that I may either end up late or even have time for a coffee before my appointment. (Thoma Reference Thoma2019, 240)

The above example is, as far as I can tell, taken from Thoma’s real life: she really does face a daily choice between the high-risk, high-reward option of taking the train and the slower-but-more-reliable option of riding her bike. But the fact that it is a real example—her example—does not make any real argumentative or epistemic difference. She could just as easily have used a hypothetical about her life: “Suppose I had to choose whether to cycle to work or take the train …”Or a hypothetical about the life of somebody else: “Suppose Person P must choose whether to cycle to work or take the train … ”Such changes would not alter the argumentative function of the example at all. Indeed, Thoma immediately slips from the real-life “bike vs. train” example to a made-up example without seeming to notice: “Or suppose that I have two options for lunch, one of which reliably produces bland food, whereas food at the other varies, with a 50 percent probability of either great or unpleasant food … [I]t does not seem unreasonable to go for the safe option in these cases” (Thoma Reference Thoma2019, 240, emphasis added). As this casual slip from the real to the hypothetical shows, the “bike vs. train” example is “personal” only in the barest, most technical sense.

In this paper, I want to explore substantively personal writing in philosophy—writing whose “personal” elements go beyond the grammatical or the merely incidental. By the time I started my investigation, I already knew from experience that writing norms varied dramatically from one subdiscipline to another. Feminist philosophers embraced substantively personal writing. So too did philosophers of disability and critical philosophers of race. Everywhere else, it was vanishingly rare. All I had was an impressionistic picture, however, and I wanted something more precise, so I decided to undertake a systematic survey. I settled on studying papers published recently in four high-ranked philosophy journals. The first pair of journals, Ethics and Philosophy and Public Affairs, I took as representatives of mainstream analytic philosophy; the second pair, Hypatia and Feminist Philosophy Quarterly, I took as representatives of feminist philosophy. (And critical social philosophy more generally: in addition to feminist philosophy, both Hypatia and FPQ regularly publish papers in philosophy of disability and critical philosophy of race.) My procedure was straightforward: I read two issues—six months of papers—from each journal, starting around 2018.Footnote 3 I ended up with a total sample of 46 papers.

If I had been interested only in the grammatically first-personal, the task of classifying these papers would have been quick. I could have simply skimmed each paper until the author used an “I” or a “me,” usually no more than a couple paragraphs; a tech-savvy researcher could easily automate the task. But I wanted to go beyond mere grammar. I wanted data on substantively personal writing, and those data, it turns out, are more challenging to collect. There are no hard-and-fast rules about when or how philosophy papers get personal. Among papers that get personal, for example, most do so within the first few pages—but it would be a mistake to assume that they all follow this pattern. For example, in her paper “Religious faith and the unjust meantime,” Theresa Tobin spends most of the paper keeping her topic—clergy sexual abuse—at arm’s length. It is only in the final two pages that she opens up about its intense personal significance for her. In a closing paragraph, she writes:

Many expressions of spiritual violence are forms of gender-based violence, and for many gender and sexual minorities, religious faith or spirituality is partially constitutive of their sense of flourishing, and it is a great loss when spiritual engagement seems forever tarnished, out of reach, or oppressive. I am one such person. Religious faith is central to my identity and sense of meaning and thriving, but I live this faith in the unjust meantime as someone who has experienced gender-based spiritual violence as a barrier to faith. (Tobin Reference Tobin2019, 25)

She goes on to describe how she negotiates tensions between her Christian faith and her commitment to feminism. If I had read only the start of the paper, I would have completely missed this important personal turn.

Given the unpredictability of when and how philosophy papers get personal, in order to collect the data that I wanted I had to read (or at least skim) each paper in its entirety. The task was time-consuming, but it also proved interesting. Usually when one does philosophical research, one traces the line of some particular topic or question or debate. Reading a journal cover to cover is a totally different experience, like learning about a species by studying a cross-section of tissue under a microscope or learning about geology by drilling straight down into the earth and extracting a core sample.

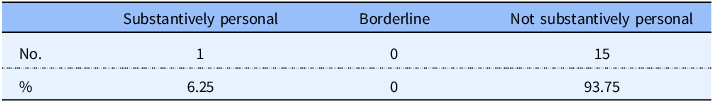

As I mentioned earlier, all 46 papers in my sample used first-personal pronouns like “I” and “me.” (No surprise there.) More important, I confirmed that, when it came to substantively personal writing, there was indeed a striking difference between the feminist philosophy journals and the mainstream analytic journals. Of the papers published in mainstream journals Ethics and Philosophy and Public Affairs, only one revealed anything about the life of its author. The other 15 were all silent about the personal (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of survey data from Ethics and Philosophy and Public Affairs (for details see Appendices 1 and 2)

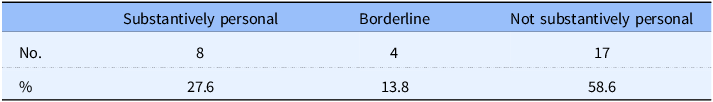

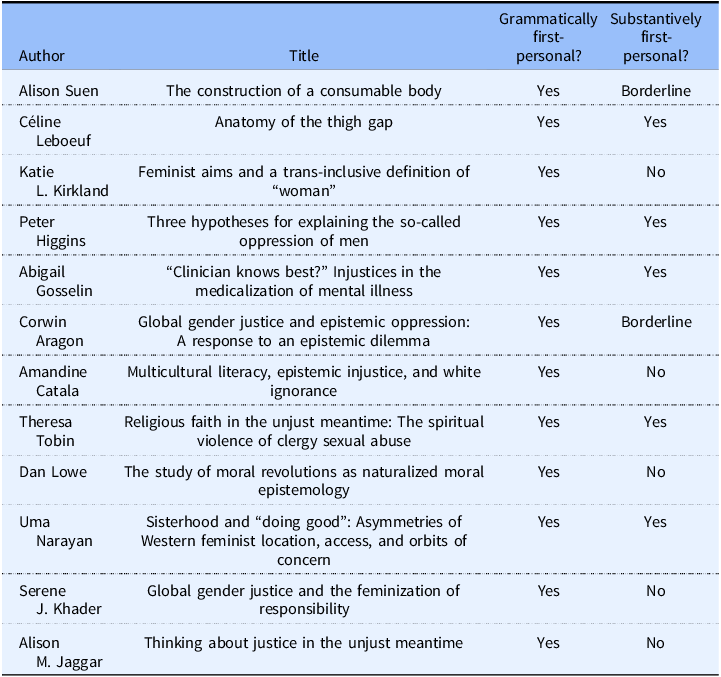

In the feminist philosophy journals Hypatia and Feminist Philosophy Quarterly, in contrast, many authors defy this “nearly sacred” impersonal tradition (Table 2). In my survey I found that, depending on how you count some border cases, roughly one in three feminist philosophy papers has a substantively personal element.

Table 2. Summary of survey data from Hypatia and Feminist Philosophy Quarterly (for details see Appendices 3 and 4)

As these data show, although personal writing may not be universal among feminist philosophers, it is widely practiced and widely accepted.

2. Understanding the impersonal tradition

How should we understand this divergence between mainstream analytic philosophy and critical social philosophy? Following feminist philosophers Susan Brison and Eva Kittay, I argue that there is far more at stake here than mere style; the divergence is a deep ideological one. The different patterns of writing track different underlying epistemologies, different conceptions of what it means to do philosophy. I have yet to find a direct defense of the impersonal tradition. (A hallmark of ideology is that it tends to make itself invisible to those who accept it.) As Brison points out, however, we can find an indirect defense in a Bertrand Russell essay called “The value of philosophy.” Russell writes:

The free intellect will see as God might see, without a here and now, without hopes and fears, without the trammels of customary beliefs and traditional prejudices, calmly, dispassionately, in the sole and exclusive desire of knowledge—knowledge as impersonal, as purely contemplative, as it is possible for man to attain. Hence also the free intellect will value more the abstract and universal knowledge into which the private accidents of history do not enter, than the knowledge brought by the senses. (Russell Reference Russell2001, 93; for further discussion, see Brison Reference Brison2002, chapter 2)

Building on Brison, I would add that this preoccupation with transcending “private accidents of history” is not unique to Russell: it is a recurring theme in analytic epistemologies, especially empiricist epistemologies. Philosophers of science Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison offer the following definition of objectivity: “To be objective is to aspire to knowledge that bears no trace of the knower—knowledge unmarked by prejudice or skill, fantasy or judgment, wishing or striving. Objectivity is blind sight, seeing without inference, interpretation, or intelligence” (Daston and Galison Reference Daston and Galison2010, 17). Similarly, Louise Antony writes that empiricism

immediately gives rise to a certain ideal (some would say fantasy) of epistemic location—the best spot from which to make judgments would be that spot which is least particular. Sound epistemic practice then becomes a matter of constantly trying to maneuver oneself into such a location—trying to find a place (or at least come as close as one can) where the regularities in one’s own personal experience match the regularities in the world at large. A knower who could somehow be stripped of all particularities and idiosyncrasies would be the best possible knower there is. (Antony Reference Antony, Louise and Charlotte2018, 123–24, original emphasis)Footnote 4

Kristie Dotson argues that one of the most devastating ways for a philosopher to dismiss a paper is by questioning its place in the discipline: “How is this paper philosophy?” (Dotson Reference Dotson2012). As Dotson points out, other disciplines are less preoccupied with such gatekeeping: “One does not call a bad short story a collection of words, except in a tongue in cheek fashion, because it is a bad short story” (Dotson Reference Dotson2012, 18). But we remain quick to dismiss papers as not even philosophy. All of this suggests a story about why philosophers tend to be so deeply committed to the impersonal tradition. The whole point of philosophy, according to the Russell tradition, is to transcend contingent particularities of birth and circumstance. Philosophers write impersonally because the “free intellect,” as Russell calls it, pursues impersonal knowledge—“knowledge that bears no trace of the knower” (Daston and Galison Reference Daston and Galison2010, 17). It seeks that epistemic position which is “least particular” (Antony Reference Antony, Louise and Charlotte2018, 123). It takes “the point of view of the universe” (Nagel Reference Nagel1989) or “the view from nowhere” (Sidgwick Reference Sidgwick1981). Personal writing is, almost by definition, unphilosophical.

We can gain further insight into philosophy’s impersonal tradition through an analogy to philosophy of science. According to a model popularized by Hans Reichenbach, philosophers of science should be concerned with the context of justification, not the context of discovery. To illustrate this “context distinction,” consider the development of penicillin. In 1928, bacteriologist Alexander Fleming left his lab for a two-week holiday in Scotland, leaving his petri dishes of Staphylococcus unattended. When he returned, he found that one of the petri dishes had been contaminated with mold and, to his surprise, the mold seemed to be killing the Staphylococcus. It turned out that a Penicillium spore had drifted into the lab—perhaps down the stairs, perhaps through an open window—and settled in the unattended petri dish. Thanks to this serendipitous chain of events, Fleming and his colleagues were ultimately able to harness the antibacterial power of penicillin, saving millions of lives and launching a new era of medicine. According to the Reichenbach model, context of discovery is the particular path that happened to lead Fleming to his discovery: the trip to Scotland, the messy lab bench, the mold spore drifting on the breeze. Context of justification, on the other hand, is the work that Fleming and his colleagues did after the initial discovery. It’s the systematic work they did to investigate the nature of penicillin and harness its power: the follow-up studies, the clinical trials, the scientific journal articles. According to Reichenbach and his followers, philosophers of science should concern themselves only with the neat, systematic work of justification. Discovery, they argued, is messy, contingent, non-rational—perhaps even a little mystical—and therefore unsuited to philosophical analysis. For any given discovery, there are countless different paths that could potentially lead to it. A scientist’s synesthesia might help her see patterns which others tend to miss, say, or an answer might come to her in a dream. But according to Reichenbach, philosophy of science should not concern itself with accidents of history or quirks of personal psychology. It should not concern itself with the contingencies of how one happens to stumble upon a scientific claim. Instead, it should focus on the rational practices that we all use (or should use) to validate such claims. Does the product work? Does the mathematical proof stand up to scrutiny? Do the data support the hypothesis?

I propose that philosophy’s impersonal tradition can be understood as a kind of “context distinction” applied to the domain of philosophy itself. In philosophy too, the thought goes, context of discovery is at best a distraction. A good argument is good, a bad argument is bad: either way, biographical details about the person who happened to write it are philosophically irrelevant.

For many years, Reichenbach’s “context distinction” defined the boundaries of philosophy of science. By the 1960s, however, the consensus had started to erode. (Some of the context distinction’s most vocal critics were feminist philosophers of science—no coincidence, in my view.) Is the distinction between “discovery” and “justification” really as tidy as Reichenbach and his followers make it out to be? Is the discovery process really as non-rational as they say, and is the justification process really as rational? By dismissing the discovery process as “unphilosophical,” do we needlessly impoverish our understanding of the world? “By the late 1980s,” write philosophers of science Jutta Schickore and Freidrich Steinle, “the context distinction had largely disappeared from philosophers’ official agendas” (Schickore and Steinle Reference Schickore and Steinle2006, ix).

3. Critiquing the impersonal tradition

In the section above, I argued that philosophy’s impersonal tradition is tied to a specific epistemic ideal. In this tradition, the philosopher aspires to occupy “that spot which is least particular” (Antony Reference Antony, Louise and Charlotte2018, 124). The philosopher aspires to occupy a “view from nowhere,” to see the world “as God might see” (Russell Reference Russell2001, 93). What should we think of this epistemic ideal? Some philosophers think we can and should attain a “view from nowhere.” Let’s call this first attitude strong optimism about the “view from nowhere.” Some think it is difficult or impossible to attain, but even so, it is a good regulative ideal: even if we fall short, striving to attain a “view from nowhere” is the best available epistemic strategy. Let’s call this second attitude weak optimism about the “view from nowhere.” Still others deny that we should even try. Let’s call this third attitude pessimism about the “view from nowhere.”

Like many women and people of color, I find myself in the pessimist camp. Here is what motivates this pessimism. Our society has a long, troubling history of trying to survey the world from a God’s-eye view and failing. These epistemic failures are not random or neutral: they tend to track—and reinforce—patterns of social power. All too often, we mistake the white for “raceless.” We mistake the male for “gender-neutral.” We think we are occupying a “view from nowhere” and fail to notice that really, we are occupying a view from a hegemonic social position. In her book Waking up white, Debby Irving offers a helpful description of this pattern as it relates to race. For most of her life, she writes,

I didn’t think I had a race … The way I understood it, race was for other people, brown- and black-skinned people. Don’t get me wrong—if you put a census form in my hands, I would know to check “white” or “Caucasian.” It’s more that I thought all those other categories, like Asian, African American, American Indian, and Latino, were the real races. I thought white was the raceless race—just plain, normal, the one against which all others were measured. (Irving Reference Irving2014, xi, quoted in Mills Reference Mills2018, 22)

In his book La pensée blanche, French soccer player and racial justice activist Lilian Thuram recounts a strikingly similar story:

One evening, I decided to call a childhood friend, Pierre.

“Hello, Pierre? How’s it going?”

“Hey Lilian, I’m good. You?”

“Listen, can I ask you a question?”

“Go for it.”

“Pierre, do you think of yourself as white?”

I sense hesitation on the line.

“What? I don’t understand what you mean.”

“Pierre, you know that I am a Black man?”

“Well, yes.”

“And if I am Black, then what are you?”

“I mean … I’m normal.”

I burst out laughing. (Thuram Reference Thuram2020, 8–9, my translation)Footnote 5

This pattern of mistaking hegemonic social positions for “neutral” or “normal” shapes all kinds of disciplines. Take journalism, for example. In 2017, trans journalist Lewis Raven Wallace published a post on his private blog called “Objectivity is dead (and I’m okay with it).” In the blog post, Wallace declares:

Neutrality is impossible for me, and you should admit that it is for you, too. As a member of a marginalized community (I am transgender), I’ve never had the opportunity to pretend I can be “neutral.” After years of silence/denial about our existence, the media has finally picked up trans stories, but the nature of the debate is over whether or not we should be allowed to live and participate in society, use public facilities and expect not to be harassed, fired or even killed. Obviously, I can’t be neutral or centrist in a debate over my own humanity. (Wallace Reference Wallace2017)

At the time, Wallace was working for the media outlet Marketplace. The blog post went viral, and his managers gave him an ultimatum: delete it or lose his job. When he refused to delete the post, they said that he clearly “didn’t want to do the kind of journalism we do at Marketplace” and fired him on the spot (Wallace Reference Wallace2019, 3). Instead of looking for work at another outlet like Marketplace, Wallace spent the next two years researching and writing The view from somewhere, a book tracing the history of journalistic norms like neutrality and objectivity and exploring the ways in which they are deployed today. His research reaffirmed his sense that, while such norms might sound innocent, they are, in practice, politically charged. Consider for example the 1990 LA Times headline “Can women reporters write objectively on abortion issues?” It’s part of a whole genre of articles debating whether or not women can be appropriately objective on the topic. Wallace points out, however,

The same questions aren’t asked about the men in Washington who attend private dinners with politicians, the Midtown Manhattan reporters who are drinking buddies with Wall Street guys, the small-town beat reporters whose dad and brother and uncle are all cops. And in fact, the same questions aren’t asked about men and abortion: clearly, a man can get someone pregnant, so shouldn’t he have a stake? Maybe conflict-of-interest questions ought to be asked of everyone, but the point is, it’s complicated. If women can’t report on abortion because they have too much personal stake in it, who can report on anything? (Wallace Reference Wallace2019, 127)

Instead of clinging to the myth of objectivity, Wallace argues, journalists should focus on norms like rigorous sourcing, factual accuracy, and transparency.

Wallace is not alone in his critique of mainstream journalistic norms. In June 2020, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Wesley Lowery published an op-ed in the New York Times titled “A reckoning over objectivity, led by Black journalists.” Lowery argues that news organizations struggle to give Black communities the coverage they deserve for a pair of related reasons. First, Black journalists remain underrepresented in the newsroom, especially in positions of power. Second, their work is subtly undermined by journalistic norms like objectivity. Objectivity, Lowery insists, has always been an impossible ideal, disconnected from realities of how journalism is practiced.

[N]eutral “objective journalism” is constructed atop a pyramid of subjective decision-making: which stories to cover, how intensely to cover those stories, which pieces of information are highlighted and which are downplayed. No journalistic process is objective. And no individual journalist is objective, because no human being is. (Lowery Reference Lowery2020)

Not only is journalistic objectivity impossible to attain, it also tends to perpetuate racial injustice. Newsroom discussions of objectivity “habitually focus on predicting whether a given sentence, opening paragraph or entire article will appear objective to a theoretical reader, who is invariably assumed to be white” (Lowery Reference Lowery2020). Challenging such practices can be professionally risky: “The views and inclinations of whiteness are accepted as the objective neutral. When black and brown reporters challenge these conventions, it’s not uncommon for them to be pushed out, reprimanded or robbed of opportunities” (Lowery Reference Lowery2020). Nevertheless, an increasing number of journalists have started taking such risks. If good journalism requires having no social location—no stake in the stories which one reports—then good journalism is impossible. After all, as Wallace reminds us, “We all have a race and a gender and a sexuality” (Wallace Reference Wallace2019, 125).

In philosophy, countless marginalized and minoritized scholars have made similar arguments. There are far too many voices in this chorus to include them all, but I’ll share a few. Virginia Held writes: “The philosophical tradition that has purported to present the view of the essentially and universally human has, masked by this claim, presented instead a view that is masculine, white, and Western” (Held Reference Held1993, 19, quoted in Brison Reference Brison2002, 24). Uma Narayan writes:

Historically, those in power have always spoken in ways that have suggested that their point of view is universal and represents the values, interests and experiences of everyone. Today, many critiques of political, moral and social theory are directed at showing how these allegedly universal points of view are partial and skewed and represent the view points of the powerful and the privileged. (Narayan Reference Narayan1988, 38)

Lauren Fournier writes: “women and racialized people have been historically overdetermined by their bodies—in contrast, always, to the supposedly neutral standard of the white, cisgender man” (Fournier Reference Fournier2021, 43). Kristie Dotson writes that professional philosophy is a context “where appeals to false objectivity carry more authority than positions that acknowledge the situatedness of perspectives” (Dotson Reference Dotson2013, 41). Susan Brison writes that, after being raped and nearly murdered, they turned to philosophy to help make sense of the traumatic experience, but they found that the existing philosophical literature was disappointing:

It occurred to me that the fact that rape was not considered a proper philosophical subject, while war, for example, was, resulted not only from the paucity of women in the profession but also from the disciplinary bias against thinking about the “personal,” against writing in the form of narrative. (Of course, the avowedly personal experiences of men have been neglected in philosophical analysis as well. The study of the ethics of war, for example, has dealt with questions of strategy and justice, and not with the wartime experiences of soldiers or with the aftermath of their trauma). (Brison Reference Brison2002, 26, Original emphasis)

Building on the work of such feminist philosophers, Charles Mills argues that we must acknowledge what he calls “the whiteness of philosophy.” Most obviously and uncontroversially, philosophy is demographically white. People of color remain dramatically underrepresented in the discipline: in the American Philosophical Association’s 2018 survey of philosophy PhD students and recent graduates, for example, only 1.5% of participants identified as Black (Dicey Jennings et al. Reference Dicey Jennings, Regino Fronda, Hunter, Johnson King and Wilson2018). But Mills also makes another, more controversial claim: philosophy is conceptually white (see Mills Reference Mills2020). As he writes,

the pretensions of the discipline are to illuminate the human condition as such, and to be typically pitched at a level of abstraction from whose distance race and gender are supposedly irrelevant. Philosophy just deals with Man and the World—oops!, I mean Person and the World. And that, of course, is the giveaway. For as feminist philosophers have been arguing for the past three decades, to the extent that these supposedly genderless “persons” are conceived of by abstracting away from the specificities of women’s experience, they will indeed be males. One simple way of thinking about my project, then, is as attempting to do for race what feminist philosophers have so successfully done for gender, showing the difference that it makes in philosophy once its implications are not evaded. (Mills Reference Mills, Valls and Ithaca2005, 169)

Thus, according to Mills, the discipline is trapped in a vicious cycle. The conceptual whiteness of philosophy persists partly because of its demographic whiteness; the demographic whiteness, in turn, persists partly because people of color are alienated by the conceptual whiteness.

Perhaps sometimes, people intentionally cast their values, interests, and experiences as universal. Perhaps it is sometimes a conscious attempt to gain or retain power. I choose to believe that more often, it is a genuine mistake. But whether intentional or unintentional, this pattern of treating hegemonic perspectives as “neutral” renders the “view from nowhere” tradition counterproductive, both epistemically and politically.

In her work on feminist standpoint epistemology, Donna Haraway refers to the (impossible) trick of occupying a neutral and universal “view from nowhere” as the god trick. She argues that people who tend to be the cockiest about their ability to successfully pull off “the god trick”—the people most likely to underestimate the importance of their own positionality—are the privileged. In contrast, “the subjugated,” as she calls them, “have a decent chance to be on to the god trick and all its dazzling—and, therefore, blinding—illuminations” (Haraway Reference Haraway1988, 584).

For the purposes of this paper, I don’t think the particulars of my own life matter much: what matters is their general shape. It doesn’t specifically matter that I grew up in a mixed racial and religious household—my mother a white woman and a lapsed Catholic, my father a Black man and a practicing Buddhist. It doesn’t specifically matter that I was assigned female at birth, or these days, depending on context, I identify as a woman or as nonbinary—queer, at any rate, and not a man. What matters is the fact that I have never had much opportunity to mistake myself for “human neutral.”

When I was a junior in high school, I decided to study abroad in France. I wanted to deepen my language skills; I had been studying French in school and I was an ambitious student. I was sent to the Nord-Pas-de-Calais, a beautiful region deep in the countryside of northern France. They didn’t get many visitors that far out in the country; when the local lycée announced that an American was coming to stay, everybody buzzed with excitement. When I showed up, however, the excitement turned to puzzled disappointment. Not long after I arrived, an older boy, almost charming in his bluntness, confronted me about the disappointed expectations. “Les américains, ils sont grands et blonds et forts,” he declared. “Toi, t’es petite et douce et brune.” Americans are big and tall and noisy and blond. You are little and quiet and dark-haired. Brown.

The boy’s words were somewhere between a question and an accusation; I was young and painfully shy, and I had no idea how to respond. “I know,” I said, shrugging helplessly. “Sorry.” This paper is informed by a lifetime of experiences like that.

4. A note on intersectionality

Throughout this paper, I move freely back and forth between categories like sex and race and disability. This is not mere inattentiveness on my part. For one thing, in practice, the boundaries between “feminist philosophy” and “philosophy of disability” and “critical philosophy of race” are blurry at best. Eva Kittay, for example, is a leading theorist in both feminist philosophy and philosophy of disability. Similarly, Charles Mills writes often about how his critical philosophy of race is indebted to the work of feminist philosophers. To insist upon artificially sharp divisions between “feminist philosophy,” “philosophy of disability,” and “critical philosophy of race” would be to ignore the reality that many scholars who work in one area of critical social philosophy also work in, or at least draw inspiration from, other areas too.

There is also a more fundamental point. As Black feminists like Kimberlé Crenshaw and Patricia Hill Collins (as well as predecessors like Sojourner Truth) have argued persuasively, race and gender are mutually constituting. (For classic texts on intersectionality, see for example Truth Reference Truth1851; Collins Reference Collins1990; and Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991.) Gender cannot be fully understood in abstraction from race. Nor can race be fully understood in abstraction from gender. For those of us who take this intersectionalist insight seriously, there can be no sharp line between feminist philosophy and critical philosophy of race: the difference is merely one of emphasis. When I call this paper a “feminist” perspective on philosophical methodology, I mean “feminist” in this intentionally loose, expansive sense.

5. Two kinds of personal writing

I want to distinguish two kinds of personal writing. Some critical social philosophers treat their lived experiences as an epistemic resource, a starting point for what they do know. Consider for example the way that Lori Watson locates herself in a paper on the metaphysics of gender. In response to those who would exclude trans women from the ambit of feminist concern, Watson describes her own experience as a cis woman:

more often than not, I am identified by others, who do not know me, as a man; I would conjecture that in everyday interactions with strangers, I am taken to be a man over 90 percent of the time. This identification started happening regularly about sixteen years ago when I cut my hair very short. (I had always dressed in “men’s clothing” since my teenage years. Add to this that I am nearly six feet tall and have broad shoulders and a “healthy” frame. This is the body I was given.) Perhaps having experienced my gender/sex so uniformly and routinely confused has allowed me to “see” things, to understand the experience of living in a world in which your body is interpreted one way and your authentic self entirely rejects that other imposed identification. I am not a man. I don’t want to be a man, trans or otherwise. I am a woman, but the overwhelming majority of humankind, men and women alike, does not yet recognize my womanhood as a way of being one. (Watson Reference Watson2016, 247, footnotes omitted)

Throughout the paper, Watson weaves theoretical analysis together with poignant personal stories—struggling daily to decide which bathroom is safest, for example, and being mistaken for her brother at a funeral. (“Imagine standing over the coffin of your dead grandfather’s body, while the funeral director turns to your father and says, ‘This must be your son, I have heard so much about,’ and all your father can say in response is a quiet ‘no, this is my daughter.’” Watson Reference Watson2016, 248). Watson’s personal writing allows her to accomplish two things. First, it gives readers a vivid sense of what it’s like to be systematically misgendered. Watson’s experiences let her “see” truths about gender that are obscure or invisible to most people; by writing about those experiences, in turn, she lets readers “see” those truths too. Second, Watson’s personal writing allows her to make an unusual and, I think, powerful move in the debate between trans-inclusive and trans-exclusive feminists. Watson’s political interests are closely aligned with the interests of trans and nonbinary people; unlike her trans and nonbinary counterparts, however, Watson can make demands on trans-exclusive feminists that they themselves recognize (or at least should recognize) as legitimate. Her argument goes something like this. I am a (cis) woman. That makes me one of your constituents. It makes me one of you. As a (cis) woman, I suffer systematic gender injustice which threatens to undermine my flourishing; that is precisely the kind of problem about which you, as feminists, should be most concerned. But the injustice I suffer is the very same injustice that my transgender sisters suffer. You cannot exclude trans women from the ambit of feminist concern: my liberation is bound up with theirs. Through her combination of personal and theoretical writing, she leverages her privilege as a cis woman to make a compelling argument for trans inclusion.

Similarly, consider the way that Eva Kittay locates herself in a paper on the philosophy of disability:

In casting doubt on some central tenets of disability theory, it is important to situate myself in this discussion. It is first as a parent that I have encountered the issue of disability. My daughter, a sparkling young woman, with a lovely disposition is very significantly incapacitated, incapable of uttering speech, of reading or writing, of walking without assistance, or, in fact, doing anything for herself without assistance. She has mild cerebral palsy, severe intellectual disability, and seizure disorders … I have been learning about disability from the perspective of one who is unable to speak for herself; and it is from her and her caregivers that I have come to have a profound appreciation of care as a practice and an ethic. (Kittay Reference Kittay2011, 51–52)

Kittay’s personal writing helps her establish her epistemic authority in several ways. For one thing, relative to the norms that prevailed in disability activism at the time she published the paper, Kittay’s stance was unorthodox, even politically incorrect; she really was “casting doubt on some central tenets of disability theory.” By describing her relationship with her daughter, she reassures people with disabilities and their allies that her (admittedly unorthodox) account is written not from a place of ignorance or indifference but rather from a place of solidarity and deep personal knowledge. For another thing, her loving portrait of her daughter gives a human face to the otherwise abstract category “people with disabilities.” All too often, philosophers theorize about people with disabilities without understanding what the lives of such people are actually like. In doing so, they risk building moral arguments on a foundation of empirical assumptions that Kittay knows first-hand to be false. Personal writing helps Kittay explain what she knows and how she knows it.

Whereas Watson and Kittay write about their lived experiences to explain what they do know, other critical social philosophers write about their experiences to be transparent about what they don’t know. They use personal writing as an exercise in epistemic humility. Consider for example a disclaimer Sara Ruddick gives at the start of her paper “Maternal thinking.”

I will be drawing upon my knowledge of the institutions of motherhood in middle-class, white, Protestant, capitalist, patriarchal America as these have expressed themselves in the heterosexual nuclear family in which I mother and was mothered. Although I have tried to compensate for the limits of my particular social and sexual history, I principally depend on others to correct my interpretations and to translate across cultures. (Ruddick Reference Ruddick1980, 347, my emphasis)

As Ruddick is acutely aware, second-wave feminists had a bad habit of extrapolating too far from their own lives. All too often, they took themselves to be theorizing the experiences and political interests of women as such when really, what they were doing was theorizing the experiences and political interests of middle-class cis white women. Their project was important, but less universal than they tended to recognize. It systematically failed to capture the experiences and political interests of women of color, colonized women, trans women … This pattern of over-extrapolation was the defining failure of second-wave feminism. Determined to avoid making the same mistake, third-wave feminists have embraced this style of disclaimer as a way of exposing their own potential biases and blind spots.

I think that moves to epistemic humility—moves like Ruddick’s—are a good idea for pretty much everybody. I recommend them, other things being equal. (I’ll say a bit about the “other things being equal” caveat later.) This kind of move is epistemically responsible, and it’s easy to implement: it can be as simple as adding a couple extra lines to an otherwise-traditional analytic philosophy paper.

On the other hand, I take moves to epistemic authority—moves like Watson’s and Kittay’s—to be fully optional; I don’t think anybody needs to make that kind of move. But still, I think it’s worth drawing attention to it. The impersonal tradition is so deeply entrenched that philosophers often censor the personal out of their work without stopping to ask themselves why. As I share drafts of this paper with my fellow philosophers, I keep having conversations that echo that first exchange with my Deaf student: “The way I think about such-and-such project has always been rooted in personal experience, but I forgot that I could just come out and say it. I forgot that we were allowed to do that.”

Watson- and Kittay-style moves are valuable largely because, compared to the hyper-abstract moves that analytic philosophers usually make, they offer so much particularity and richness. But stories from one’s own life are not the only sources for this particularity and richness. It can also be found in stories from the lives of friends and family, in memoirs and interviews and diaries—even in fiction, if it is sufficiently grounded in the real world. Even when your story matters for some philosophical argument, it is a further question whether it matters that the story is yours. I think the answer varies from case to case. In some cases, it does matter that the story is yours. In others, it matters that the story belongs to somebody, but being yours makes little difference. Even in the latter kind of case, however, I don’t think it does any harm to claim the story as your own. The instinct to obscure that ownership is a mere vestige of the impersonal tradition.

6. Personal writing: risks and rewards

In this paper I have argued that philosophers have good reason, both epistemic and political, to abandon the impersonal tradition. However, I do not claim that these are always decisive reasons: in some cases, they might be outweighed by other considerations. Consider a comment Simone de Beauvoir makes at the start of The second sex:

I used to get annoyed in abstract discussions to hear men tell me: “You only think such and such a thing because you’re a woman.” But I know my only defense is to answer, “I think it because it is true,” thereby eliminating my subjectivity; it was out of the question to answer, “And you think the contrary because you are a man,” because it is understood that being a man is not a particularity; a man is in his right by virtue of being a man; it is the woman who is in the wrong. (Beauvoir Reference Beauvoir2009, 5)

The assumption that Beauvoir identifies in her audience—that womanhood is a “particularity” while manhood is “not a particularity”—is, of course, nonsense. But she is savvy enough to know that if she pressed the issue, she would lose. Her already-hostile male audiences would dismiss her outright. And so, begrudgingly, she retreats away from her own subjectivity, back to the “view from nowhere.” I want to make it clear that I understand Beauvoir’s retreat. For those underrepresented in the discipline—those who do not look like the typical philosopher—making an active effort to talk and write like the typical philosopher can be a way of fitting in. Stylistic and methodological conservatism can be a method of self-protection. I have no interest in criticizing minoritized philosophers who choose this path.

Similarly, consider the situation of an early-career scholar: a student applying to graduate school, say. The grad school applicant might have good pragmatic reasons to construct her writing sample in the style of a mainstream professional paper. Obeying disciplinary conventions can be a way of making one’s work legible as philosophy. It can be a way of saying: I understand the norms of this academic community. I am one of you. The more professionally established one gets, however, the less weight such conventionalist considerations should carry. At a certain point, your role is not simply to obey the conventions of your discipline: it is to help shape them. Suppose a junior scholar asks a well-established colleague, “Why should we do things this way?” To simply answer “because we’ve always done things this way” would be conservative to the point of absurdity.

While I understand the professional risks, at this point in my career, I have lost interest in obeying the conventions of detachment and impersonality. I’ve lost interest in writing like a Russellian “free intellect.” I no longer pretend to see moral and political questions from “the point of view of the universe.” Now that I have stopped stripping myself out, my work feels more exciting and more authentic to the way I think. If writing this way puts me outside the philosophical mainstream, fine. I can live with that. In the words of Kittay (Reference Kittay2009), the personal is philosophical.

Acknowledgments

For generous and incisive feedback on drafts of this paper, I owe thanks to many people, including Ido Ben Harush, Carolin Benack, Giacomo Berchi, Stephen Bloch-Schulman, Susan Brison, Stephen Darwall, Robin Dembroff, Jill Drouillard, Max Duboff, Brian Earp, Adam Ferner, Abigail Gosselin, Dan Greco, Austen Hall, Allison Raven, Matt McWilliams, Lewis Raven Wallace, Adam Waters, and Gideon Yaffe, and to audiences at the following conferences: The Great Lakes Philosophy Conference, The Mark L. Sanders Graduate Philosophy Conference, The Society for Philosophy in the Contemporary World, The British Society for Ethical Theory, The CUNY Graduate Philosophy Conference, and the APA Eastern. I am also grateful to the members of my 2021 Feminist Ethics seminar: Mafalda von Alvensleben, Mina Caraccio, Sonnet Carter, Isabel Coleman, Claire Donnellan, Joy Liow, Eliza Lord, Angel Nwadibia, Darcy Rodruiguez Ovalles, Gabby Servillano, and Sarah Teng. Finally, thank you to Hypatia editor Aness Kim Webster and two anonymous referees.

Appendix 1

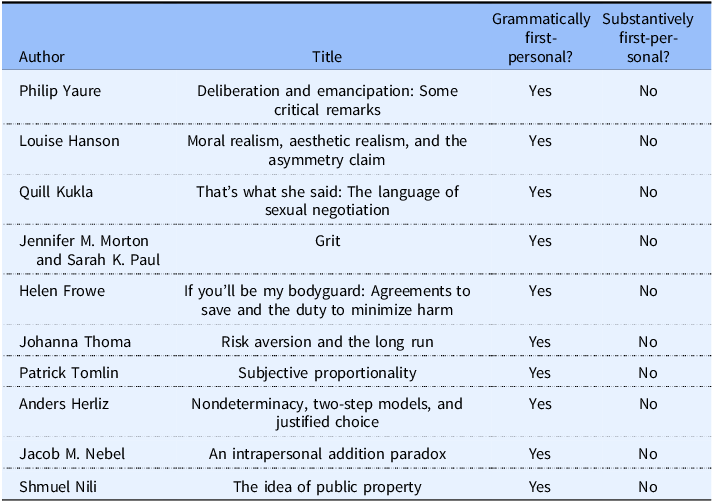

Survey results from Ethics 129 (1 and 2) (Fall 2018–Winter 2019)

Appendix 2

Survey results from Philosophy and Public Affairs 47 (1 and 2) (Summer 2019–Fall 2019)

Appendix 3

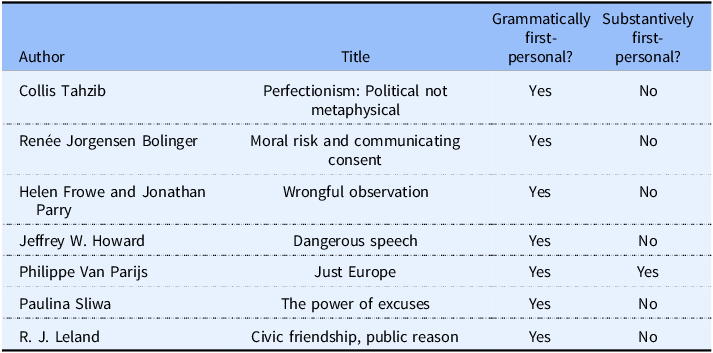

Survey results for Hypatia 34 (1 and 2) (Winter and Spring 2019)

Appendix 4

Survey results for Feminist Philosophy Quarterly 5 (1 and 2) (Spring and Summer 2019)

Moya Mapps received their PhD from the Yale Philosophy Department in 2023. They are currently a Postdoctoral Fellow at Stanford’s McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society. Their work explores moral, social, and political philosophy.