I. The WorkFootnote 1

Genizah scholars have been conditioned by necessity to collect fragments of a work scattered in several different libraries to reconstruct them, to the degree possible. Exceptional in this regard is the Karaite Genizah in St. Petersburg, which was transferred there almost intact by Abraham Firkovich. This accounts for the appearance of continuous, nearly complete works in the Firkovich collections of the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg. One such work is a new additional and different vision of Daniel from the St. Petersburg Genizah, the subject of this article. The article includes the first complete transcription and translation of the Vision of Daniel as it survived, albeit incomplete, in a sole manuscript from the St. Petersburg collection. The article includes a comparative study of related versions of a parallel work, enabling a reconstruction of its missing part.Footnote 2

A. Physical Characteristics, Date, and Provenance of the MS

The copy of the Vision under discussion, written in Hebrew in a Byzantine script, was made in the fourteenth century. The beginning is fragmentary, and its content is reconstructed herein based on a detailed comparison with another vision attributed to Daniel, similar in many respects to this Vision. After the Vision, the copyist of this manuscript copied a story about a child and the Book of Genesis (three pages)Footnote 3 and a chapter on the fast days (seven pages).Footnote 4

This fragmentary copy of the Vision has no title, but it should be described as a Vision of Daniel since Daniel is mentioned three times as having heard (Appendix, f. 2b, ll., 1,3; f. 4a, l.7) things from an angel. The author of this work concludes with a passage that indicates that he viewed the work as a vision that Jeremiah, Elijah, and Zerubbabel instructed him to write down, and which he revealed to Ezra the Scribe.

The Vision was written originally in typical medieval literary Hebrew. The main part of the Vision was composed in the mid-ninth century in the borderlands between Muslim Syria and Byzantium. Both time and place are established on the basis of historical figures and events described in detail within the Vision.

B. Contents and Outline

The missing parts of the Vision of Daniel can be reconstructed with a high degree of probability by comparing it with parallels in other visions, chief among them being chapters 7–12 of the biblical Book of Daniel. Several versions of redemption have a similar structure, including a prophetic introduction, in which: 1) an angel brings tidings of the eschaton to the visionary; 2) a prophetic-historical section relates to events that transpired and to characters who were active as a “prophecy after the event” (vaticinium ex eventu); 3) the apocalyptic vision is described.

In general, the visions, including the names of rulers, are written cryptically and allusively. The era and events of their rule are encrypted in code-names, numerological calculations, and oblique references, if only to give them the aura of prophecies about future events. The writer foretells the future, and the reliability of the vision extends from historical figures and past events to descriptions of the eschaton.Footnote 5

The structure of the Vision of Daniel is similar to that of biblical Book of Daniel, and, as will become evident in the discussion below, it is likely that the content of the Vision is almost identical to that of the Judeo-Persian vision named Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl,Footnote 6 where, as in the Vision of Daniel, an angel reveals to Daniel a portrait of the end of days, including the rise to power of a series of rulers and an accounting of the duration and features of each of their respective reigns. There, the first rulers in the series are Persian Zoroastrians. Afterward there is a gap of four centuries, whereupon the list continues—as in The Vision—with Ishmaelite rulers, the first of whom is Muḥammad. This information about the rulers is likewise part of the vaticinium ex eventu whose realization, as it were, gives greater validity to prophecies about the future.

We will content ourselves with a study of the introduction to the list of rulers in Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl, as it is presumed to be similar to the missing introduction of the extant Vision of Daniel fragments.Footnote 7

As will be proposed in greater detail below, the close relationship between these two works makes it likely that their similarity extends to their respective openings. Thus, the first part of the Vision of Daniel presumably recounts, as does Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl, how Daniel prayed to God for salvation, as Jerusalem had been destroyed. God sent him an angel to illuminate for him the redemptive process, with reference to historical events. Dan Shapira has shown that the Judeo-Persian text of this part of the work is an abbreviated translation and reworking of sources that the author of Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl had before him.Footnote 8

Outline of the Vision of Daniel:

[I. The revelation of the word of God to Daniel reconstructed from Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl

1. Daniel’s prayer to God for salvation

2. God sends an angel to illuminate for Daniel the historical-redemptive process

3. The angel brings tidings of the eschaton to Daniel]

II. Signs of the messiah: vaticinium ex eventu; the prophetic-historical section; events and characters

1. The “exact” Umayyad list of the kings of Ishmael

2. Early Abbasid caliphs

3. The “vague list” of the kings of Ishmael

III. Pre-messianic pangs

1. The son of Levi’s daughter with Gog and Magog

2. Armilus, son of the She-Statue

3. Messiah, son of Joseph

4. The flight to the desert

IV. Redemption

1. Extermination of the remaining evildoers

2. Resurrection of the dead

3. Rebuilding of Jerusalem

4. Ingathering of exiles

5. The age of the messiah: eternal life; the banquet of messiah; kingship; and priesthood

V. Conclusion

1. Daniel finds the vision comforting and uplifting

2. Elijah, Zerubbabel, and Ezra instruct Daniel to write down the prophecy

3. The angel instructs Daniel to seal The Vision until the time of Israel’s salvation.

II. The Prophetic-Historical Sections of the Vision of Daniel

A. The Vision of Daniel and Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl

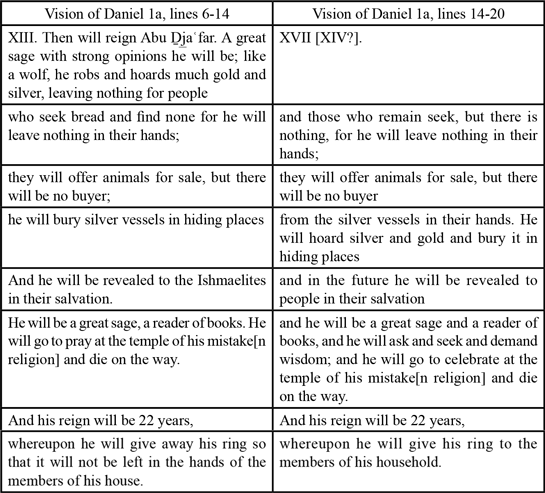

The vision of the future that begins with a list of rulers constitutes a return to the pattern established in the visions of the biblical Book of Daniel chapters 7 and 11.Footnote 9 Our Vision of Daniel is easier to read than most other visions, because its author details each ruler by number, name, years of activity, and deeds. It stands to reason that this level of detail was provided by a later redactor-interpreter who incorporated the identifications and made explicit what the earlier writer left vague. This can be seen from the description of the reign of the Abbāsid Caliph Abu Ḏj̲aʿfar al-Manṣūr, a description that appears twice in the Vision of Daniel, one after another, with the second interpreting the first:

Both versions include the same details, using almost identical terminology; the author interpreted one text by means of a similar variant. Perhaps the text from which the copyist worked contained the other variant in the margins or between the lines, and the copyist of our manuscript then incorporated it, with all its mistakes, into the main flow of the text. Alternatively, perhaps he was not careful and simply copied these sections twice.

Among the details copied is the number XVII, which originally designated the next ruler (XIV), or the fourth ruler after Abu Ḏj̲aʿfar (XVII). Either way, this interpolation and the consequent disruption of the text’s linear flow caused the omission of the rulers’ ordinal numbering. This narrow window into the modus operandi of the author or copyist of the Vision indicates later stages of correction and redaction of the original text, including the apposition of ordinal numbers to the names of rulers. Abu Ḏj̲aʿfar al-Manṣūr indeed ruled for twenty-two years. He founded Baghdad and built the new official residence of the caliph, Madīnat as-Salām, around which the city developed. He did much to cultivate the city as the capital of the Islamic empire. The historian al-Ya‘qubi describes Abu Ḏj̲aʿfar’s accumulation of gold and silver.Footnote 10 As for the ring mentioned in the Vision, it may allude to his naming of a successor before his death. Abu Ḏj̲aʿfar died in 775 while making a religious pilgrimage to Mecca. He was buried at an unknown site on the road to Mecca.

Not all the descriptions of rulers in the Vision of Daniel fit the known historical facts about the duration and features of their reigns. Sulaymān ibn ‘Abd al-Malik was the seventh Umayyad caliph and the eleventh caliph after Muḥammad. He reigned for two years (715–717), not ten. Here he is listed as the tenth caliph, and there are several ways to account for this discrepancy. For one, some Syrian and Syrian-influenced apocalypses and histories do not list Ali as even having been a caliph. Another possibility to consider is that Sulaymān is called the tenth because Mu‘awiya II, who died as a child, is omitted from this list, though included in other official lists.

The brief description in the Vision of Daniel can fit with his reign, which is characterized by military campaigns in the east and west, against various powers, including the Byzantine Empire, Djurdjān, and Ṭabaristān, which were then part of the Persian sphere. The number of years and the description of his deeds fit better with the tenth caliph, Sulaymān’s brother, Al-Walid I, and “head to the sages” is a more apt description of their father, Abd al-Malik ibn Marwān (685–705), who was considered a learned ruler.

The two sources, Vision of Daniel and Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl, are juxtaposed below according to the order of rulers, so as to clarify the connection between them.

A close study of the two traditions about the order of Ishmaelite kings whose reigns precede the redemption indicates that they both derive from a single tradition. The Vision of Daniel is more polished and orderly, not only because it gives names and ordinal numbers for each ruler, but because it provides details about the reigns of most of the rulers.

B. Time, Place, and Language of the Vision

In both traditions, the lists of Muslim rulers do not end with the heirs of Hārūn al-Ras̲h̲īd in the ninth century. They continue to other rulers, though their identification is not as obvious, and the contents of the two traditions are not as similar. Likewise, the contents of the last, apocalyptic sections of the two traditions differ. The differences with respect to later Muslim rulers and the apocalyptic section indicate that the war of the three brothers and their reigns marked the endpoint of the tradition. The works were written soon after those events, and the events and rulers that appear afterward, in both works, are the updates of authors-copyists. They updated the time of the beginning of the eschaton to their own days.

Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl stops in the middle of the period of strife between the three sons of Hārūn al-Ras̲h̲īd. It gives a brief description of the reign of al-Amin (809–813) and adds a sentence that summarizes the brothers’ struggle. From there it goes on to describe a Shia revolution in the caliphate.Footnote 12

The Vision of Daniel goes on to describe, with a continuity and clarity that are similar to the earlier descriptions, another brief period: the reigns of al-Maʾmūn (813–833) and his brother al-Muʿtaṣim (833–842). Al-Maʾmūn ruled the caliphate for twenty turbulent years. The Vision of Daniel describes them thus:

After him, his brother will reign in his place: And after him will reign an officer from his family, Muḥammad by name, and people will change his name. God will bring success to his kingdom, and his enemies will be given in his hands; he will strike and stir up the city of the South, and they will bring him much money from everywhere. And the land will be desolate, and he will die. In his life he will change many things in his kingdom, and he will love building; all his days he will be involved in building. (1b ll. 15–20)

The reign of Abu al-ʿAbbās Abdallah al-Maʾmūn, the eldest son of Hārūn al-Ras̲h̲īd, is characterized by a flourishing of science and culture. During his reign, many places of study and learning were established, including the Bayt al-Hikmah, a center for scientific study that included a large library. Shortly before his death (October 8, 833), he named his brother Ḳāsim as his successor, under the name al-Muʿtaṣim.

Al-Muʿtaṣim first ruled the eastern regions of the caliphate, and afterwards he mounted a successful military campaign against Egypt even while al-Maʾmūn still reigned. Al-Muʿtaṣim’s entire nine-year reign (833–842) was filled with revolts and wars, in the east and the west: Hamadan, Khurasan, Iraq (against the Khwarezmians and against the Zutt, who, after their defeat, were paraded through Baghdad and then sent to fight against the Byzantines). The description of the nineteenth ruler in the Vision of Daniel fits the career of al-Muʿtaṣim:

After him another king from the East will come with a large force and will reach the country of Babylon. He will capture it and shed much blood. And from there he will go to the West, and against him will stand the He-Goat whose name is Ẓafini/Ẓufyani, and they will both do battle, and he will kill the He-Goat, and the Easterner will come to Egypt, and lay it waste. He will shed an inestimable amount of blood therein. And he will turn back and come to Damascus and shed blood in it like water. (1b–2a)

The “He-Goat” is the description given to the king of Greece in the biblical Book of Daniel (8:5, 8). Indeed, al-Muʿtaṣim and his army waged a series of battles against the Byzantine Emperor Theophilos (829–842). The war began with the Byzantine attack on several ʿAbbāsid fortresses along the border between the two realms. The ʿAbbāsid army defeated Theophilos at the Battle of Anzen on July 21, 838. Ankara fell to the ʿAbbāsids, who went on to conquer other Byzantine territories, including Amorium, the cradle of the dynasty to which Theophilos belonged. The battles between al-Muʿtaṣim and Theophilos involved vast territories due to the alliances that Theophilos had made with regions abutting the ʿAbbāsid Caliphate and because the outcome of the battles varied each time.

Life in the battle zones was prone to both Christian and Muslim propaganda, which accompanied the battles that seemed as though they would determine the fate of the world. Such a historical setting is liable to become an incubator of eschatological visions for each warring party and for minorities in the war-torn regions. Some of them, like the northern Danube and Bulgaria, were forcibly dragged into military campaigns. It is easy to see the appearance of a Byzantine king and the recurrent battles against the ʿAbbāsid Empire as the realization of the vision of the beasts in the biblical Book of Daniel and the requisite defeat of the king of Greece as a stage that heralds the end of days. This is likely the reason for calling the king of Greece in the Vision of Daniel by the moniker by which he is called in the biblical book, “the He-Goat,” and this is the “historical” endpoint of the Vision of Daniel’s composition—after the winter of 842, when Theophilos died.Footnote 13

To the military and political tension in the ʿAbbāsid realms during the reign of al-Muʿtaṣim we may add an episode of revolt that occurred in the margins of the main events in the caliphate, in Transjordan and Palestine. This episode bothered the caliph and generated a great deal of interest among residents of the area near the revolt, and especially the residents of Jerusalem, Ramle, and Nablus. In 841, the revolt of Abū Ḥarb Tamīm broke out in those regions, the latter known as al-Mubarḳaʿ (“the Veiled One”; he covered his face so he would not be recognized). It was said that al-Mubarḳaʿ was from a Yemeni tribe (al-Yamānī), and according to some sources he went up to Jerusalem and put its population—Muslims, Christians, and Jews—to flight. Those same sources say that he burnt down mosques and churches, was about to burn down the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, and dealt a terrible blow to the Samaritan community in Nablus. Abū Ḥarb attracted a group of adherents through his preaching and moralizing; his band of believers found refuge in the highlands of Urdunn (around the Sea of Galilee). His charismatic leadership earned him renown, and some ascribed to him the authority of a messiah-rebel against the ʿAbbāsids, who would restore the throne of the caliphate to the Umayyads. Indeed, his conquests reached as far as Damascus, which he flooded with the blood of his victims.

A messianic figure to whom are attributed designs to restore the Umayyad caliphate was known in Muslim tradition as “al-Sufyānī.” The demonic characteristics of an enemy of the messiah and the world were ascribed to him; this sometimes included an unnatural, fearsome visage.

Perhaps the author of the Vision of Daniel refers to al-Sufyānī among the enemies of al-Muʿtaṣim when he writes, “the He-Goat (Ẓefir ‘Izim) whose name is Ẓafini,” for the Hebrew “Ẓafini” (צפיני) can be vocalized as Ẓ/Sufyānī (צֻפְיַנִי/סֻפְיַנִי). Abū Ḥarb, like Theophilos, waged war against al-Muʿtaṣim, and eschatological feelings could have developed around his campaign, particularly in connection with the devastation that occurred in Jerusalem and Nablus. It follows that the combination of the He-Goat and al-Sufyānī could have become a generic name for all of al-Muʿtaṣim’s enemies.Footnote 14

The information that we have accumulated thus far demonstrates the writer of the Vision of Daniel’s familiarity with Muslim history. The time of its composition and the events that underlie the determination that the time of redemption had arrived indicate that the work may have been composed in the area where al-Muʿtaṣim battled Theophilos: the areas of northern Syria and Anatolia bound by Aleppo, Antioch, Tarsus, and Edessa. Alternatively, it could have been composed in the region where the agents of al-Muʿtaṣim battled Abū Ḥarb Tamīm, known as al-Mubarḳaʿ, namely, in Palestine. Both took place in the year 842.

We can also determine the language in which this tradition was written and the stages of revision it underwent before arriving at the extant versions. The fluency of the text of the Vision of Daniel and its integration of certain turns of phrase attest to its composition in Hebrew. Aharon Maman of Hebrew University’s Department of Hebrew Language confirmed this conclusion after a meticulous reading of the text. He concluded his note: “On balance, the work is of a high Biblical stylistic register, riven with quite a few Rabbinic expressions and a few medieval ones. The work seems to have been composed in Hebrew originally, though there are a few instances where foreign influence, like Arabic, might be detectable. In general, the language is clear and typical of medieval literary Hebrew.” The prophetic style of the Vision draws on the biblical Book of Daniel to present itself as prophecy and cites Scripture passim as a proof to its direct revelation, even if by means of an angel.Footnote 15

Shapira proposes that the middle part of Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl, which describes the gentile kingdoms, is an independent work based on the Vision of Daniel. Shapira maintains that Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl is not an original composition. He further proposes that there is a connection between the middle part of the work and Shia Iranian apocalypses of the type known as “malāḥim, Malḥamat Dāniyāl.”Footnote 16

C. “Updating” the Vision

At the endpoint of the Vision of Daniel, after the winter of 842, when Theophilos died, the author goes on to describe the massive battles that portend the eschaton, marking them with a new introduction: “After all of these.”

At some point between the 840s and the late-tenth century, someone attempted to “revive” the Vision and add another bit of prophecy around the year 1000, a century-and-a-half after the age of al-Muʿtaṣim and Theophilos. The addition of a short passage foretells the rise of the Fāṭimids:

Then the sons of Fāṭima will crown 5 kings: The name of the most senior among them is Mahdi, and his reign will be 3 years. In their days, there will be sword, pestilence, and famine: and they will be erased and pass from the world as though they never were. (2a ll. 1–4)

Thus, the author concludes the list of twenty rulers who will reign before the eschatological vision transpires. Al-Mahdī, ʿUbayd Allāh, 909–934, was indeed the founder of the Fāṭimid dynasty, but he reigned for 24 years, not 3, as recorded in the Vision. Of the first five Fāṭimid kings, none ruled only three years, bringing the eschatological moment of the Vision to the proximity of year 995. We could hypothesize that this addendum was written in that time, when the confluence of world events could have led the one who updated the Vision to the conclusion that he was witnessing both the end of the Fāṭimid dynasty and the imminent unfolding of the eschatological moment. The events, dates and acute messianic expectations that the author of the addendum probably had in mind or could be influenced by include:

1. The death of the fifth Fāṭimid king al-‘Aziz in 996 bringing the five Fāṭimid kings scenario to a close.

2. A series of major revolts; the Tyre revolts, aided by a number of Byzantine attacks against Egypt and Syria, led by Emperor Basil II, took place in 996.Footnote 17

3. A major earthquake in the Damascus area and the Ba‘lbak region, where a village got swallowed up by the earth in 991.

4. A plague of locusts in 993 and a major famine in Egypt in 997.Footnote 18

5. The easterner, “the king from the east,” could hypothetically have been seen (by that time) as the Qarmatians, since they did come from the east, shed plenty of blood, waged multiple battles in Syria, and terrorized Syrians all the way through the third part of the tenth century.Footnote 19

6. This time was just before the year 400 AH and close to the end of the millennium CE, thus producing messianic fervor among Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike.Footnote 20

7. Another apocalyptical text, found in the Cairo Genizah and reconstructed and edited by Moshe Gil, refers, according to Gil’s reconstruction, to the 990s. This text is an updated version of the Apocalypse of Zerubbabel.Footnote 21

8. In historical and apocalyptical writings of these years one can find, again, al-Sufyānī.Footnote 22

With regard to the dating and the relationship of the Sufyānī snippet at the end of the earlier section of the apocalypse, and then to the Fāṭimid update, one might consider that while the identification of Al-Sufyānī in the original apocalypse was with al-Mubarqa‘, the fact is that there was a whole series of Sufyānī appearances in Syria, all the way up to the 1400s. Perhaps the removal of such a key figure was taken as a sign that the dynasty was at a close. The writer of the Fāṭimid section was living in greater Syria (because it does not seem likely that many outside of Syria would know about Al-Sufyānī or care about him by the late 990s), and there was another Sufyānī appearance at that time, just as there were a whole series of revolts against the Fāṭimids. Someone in Syria looking for the apocalypse at that point might note the bloodshed, followed by Al-Sufyānī’s appearance and the end of the Fāṭimids. Although one could say that such disasters are always occurring somewhere, apocalyptic predictions are so often sparked by a confluence of events where each confirms the others as being significant. During the last decade of the tenth century, the apocalypse might very well have seemed to be coming to pass, so the visions predicting it were worth updating. Thus, contrary to the statement of the Vision, the dynasty was not destroyed after five rulers. Another nine Fāṭimids reigned in Egypt until 1171. The abbreviated, mistaken, and deficient update indicates that it was a late addition to the text. The author of the updated part of the Vision estimated that the dynasty would have five rulers in order to keep to the pattern from chapter 7 and the beginning of chapter 11 of the Book of Daniel: There will be three kings in Persia, the fourth will have great wealth, and the fifth will be a warrior. After the fifth king, the eschaton will come to fruition.Footnote 23 If the Vision of Daniel was indeed before the author of Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl, then the latter described the Fāṭimids as conquerors who arrived to remove the most identifiable sign of the ʿAbbāsids—black clothes—and replace them with white garments.Footnote 24

The descriptions of the end of days in the Vision of Daniel and Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl are also similar in most of their details, and both resemble a collection from the descriptive tradition of the apocalyptic literature. This has been described and discussed at length in the scholarly literature. Its components, many already detailed in Sefer Zerubbabel, are: the appearance of a terrible giant with clearly physical features, named Armilus; Armilus kills those among the gentiles and Israel; Gog and Magog arrive, and the people of Israel are persecuted; the nations of the north, south, and west gather together; decrees against religion are propagated, and Armilus claims to be the messiah; Armilus is tested in the performance of signs and wonders, and he partially succeeds; Messiah ben Joseph, arrives, wages war against Armilus, and is killed; the remnants of Israel flee to the desert; Daniel prays for Israel in its distress; the angel appears and foretells a turning of the tides for Israel—they will prevail; Messiah ben Joseph will be resurrected and will successfully battle Armilus; the dead will be resurrected; Israel’s diaspora will be gathered to Jerusalem; Jerusalem and the Temple will be rebuilt; the Temple will function once again.Footnote 25

These details do not appear in every work, nor do they appear in the same order. The order of events, the names of the people associated with the messiah and the process of redemption, the details of the redemption of the people, the redemption and rebuilding of Jerusalem—these all vary from vision to vision. However, with respect to all of these elements, the Vision of Daniel and Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl are almost completely identical.Footnote 26 Nevertheless, the Vision of Daniel has several singular details that do not appear in Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl. They primarily relate to the two enemies of the messiah: the Son of the Daughter of Levi and Armilus.

In two apocalyptic sources, apparently written in Syria, the Son of the Daughter of Levi appears as a figure preceding the advent of the savior-enemy, the antichrist or Dajjāl. The Syriac Apocalypse of Daniel and the Syriac Apocalypse of Small Daniel (first third of the seventh century) state:

It will be in those days; a woman will bear a son from the tribe of the house of Levi. And there will appear on him these signs: something will be represented on his skin like weapons of war, the details of a breastplate, a bow, and a sword, a spear, an iron dagger, and chariots of war. His countenance will be like the countenance of a burning furnace, and his eyes like burning coals. Between his eyes, he has a horn whose tip is broken off, and something, which has the appearance of a serpent, is coming out of it. (89, v.2)

A similar Syrian Muslim tradition, the apocalyptic work of Nuʿaym b. Ḥammād al-Marwazī (pre-844), reported that before the appearance of the Dajjāl it is said that a son will be “born in Baysan from a tribe belonging to Levi ibn Yaʿqub. In his body are the signs of a sword, a shield, a lance and a knife.”

In a separate discussion, dedicated to the enemies of the redeemer, I propose that the Vision of Daniel is a Jewish inversion of the Christian and Muslim anti-messianic concept. Jesus will reveal himself again in the future, but not as a messiah (christos), rather, as an “anti-messiah” (antichrist). This procedure, in which one group’s messiah is deemed the antichrist by another group, is common in Jewish, Christian, and Muslim apocalyptic literature. The Vision of Daniel internalizes both the Qur’anic view that identifies the first Moses with the second Moses and the Christian concept of Jesus’s second coming at the end of days, thus turning it on its head. To the description of the two figures of the messiah’s enemies in the Vision of Daniel, based on the two principles that are most fitting for inverting the description of the figure of Jesus in Islam and Christianity—miracle-working and the messiahship—demonic elements are added. These demonic elements are found in ancient Christian and Jewish traditions that describe Gog and Magog and Armilus.

The uniqueness of the Vision of Daniel lies in the image of the Son of the Daughter of Levi. The combination of these two figures in the Vision reflects the shifting of the identities of those who are considered messiahs who will reveal themselves once again (Parousia) in Christian and Muslim literature; they become demonic antichrists in the eyes of the author of the Vision. In the Vision of Daniel, one of the two is the inversion of the Christian image of Moses/Jesus, whereas the second antichrist is the canonic Armilus, charged with significance.Footnote 27

III. Redemption in the Vision of Daniel and Other Visions

Among the visions of redemption composed by Jews in the medieval era, few have survived, and these were attributed primarily to Zerubbabel and Daniel. This contrasts sharply with other genres of writing from that era—works of law (halakhah), philosophy, legends and stories, liturgical and lyrical poetry, and linguistics—of which many works have survived. Nevertheless, the relative rarity of this genre does not indicate the importance of hope for redemption and the interest it held for people of that era. The presence of hope for redemption and the end of days is discernible, in varying levels of tension and activism, in exegesis and matter-of-fact statements in most conventional literary genres.Footnote 28

Visions of redemption are unique in that they present a concrete, detailed picture of how redemption will play out, relying on the significant authority of the visionary and premised on a solid, “factual” basis, namely, the fulfillment of prophecies specified in the vision. The apocalyptic discourse that followed the withdrawal of the Fourth Empire—Rome—was copied into an examination of the history of the Arabic Caliphate. That is, a schema that had already been fixed into consciousness had to undergo a paradigm shift. However, the intensity of the Persian and Arab conquests was such that it required an update to this paradigm, and this was settled long before the composition of the Vision of Daniel under discussion.Footnote 29

As a class, visions of Daniel are common in Christian apocalyptic visions and several Muslim ones as well, because the Book of Daniel is the only book in the Hebrew Bible that contains an apocalyptic vision, making Daniel a convenient attribution for pseudepigraphic writers. To this unique feature we can add the fact that the vision in the Book of Daniel is opaque, leaving plenty of room for later writers of visions to use his name and the central motifs of his book in their own works, expanding on his descriptions, projecting his writings and their knowledge of their own times onto a “past future” that is being realized before their eyes, and continuing from there to an apocalypse that conforms to the patterns that had crystallized in the apocalyptic literature. This class of “Visions of Daniel” includes many dozens of works, written in various languages from late antiquity until the late medieval era.Footnote 30

In positioning the Vision within the larger contexts of post-rabbinic apocalyptical works and the re-emergence of robust early mediaeval apocalyptic speculation during the seventh through ninth centuries, one sees similarities in motifs and events that have been mentioned already above, all in the context of major events that took place in the Middle East while empires clashed with one another. The time and spiritual climate were ripe to accept such writings and update them to fit with their agonies and hopes. Focusing on several motifs from the “scenery” of the redemption can indicate certain commonalities:

A. The Burning of the Wicked

Towards its end, the Vision describes the ultimate punishment of the enemies of the redeemer:

And the son of Jesse will burn all the wicked ones with the breath of his lips, and he will cast their carcass to the earth, where the fowl of the sky will eat them, as will the beast of the earth. And for seven years the Israelites will not need wood for kindling in their ovens, for they will burn stakes of broom shrubs from the peoples. (3b)

This tradition, based on Ezekiel 39:9, the third prophecy about Gog and Magog, is discussed in the Book of Elijah,Footnote 31 which states:

And then the Holy One, blessed be He, will raise up Gog and Magog and all of its branches, and then all of the peoples of the earth will gather and surround Jerusalem, to wage war against it. And the messiah will arrive, and with the help of the Holy One, blessed be He, will wage war against them.. . . And the Holy One, blessed be He, will gather all the birds of the heaven and the beasts of the land to eat of their flesh and drink of their blood for twelve months…. And Israel will use their weapons for kindling for seven years, as it is said (Ezek 39:9), “Then the inhabitants of the cities of Israel will go out and make fires and feed them with the weapons—shields and bucklers … ; they shall use them as fuel for seven years.”

The Vision of Daniel specifies that the kindling will be stakes made of broom-wood due to a tradition about how long they burn; this traces back to another Jewish tradition, from the sixth century:

And not just any coals, but the coals of broom-wood (Ps 120:4); all other coals, if they are extinguished outside, are also extinguished inside. However, coals of broom-wood, even if they are extinguished outside, they still burn on the inside…. It happened with one broom shrub that they lit a fire with it and it remained lit for eighteen months, a winter, a summer, and a winter. (Gen. Rab. 98:19)

B. Heavenly Jerusalem

The full redemption detailed in the Vision describes the miraculous rebuilding of Jerusalem and resumption of the Temple service: “And the Living God will lower Jerusalem already built, from heaven, with chains of iron, and He will set it upon four [mountains]: Tabor, Carmel, Hermon, and the Mount of Olives: And the heavens and the earth will be renewed and they will build Jerusalem with precious stones and gems.” (3b)

These lines reflect several biblical passages from Isaiah, Zechariah, and Ezekiel that describe the greatness of the future Jerusalem. “Heavenly Jerusalem” was a dominant motif in the scenery of the redemption and is mentioned in other apocalyptical works. The tradition about the descent of the Temple from heaven and the links between this tradition and Christian traditions have been discussed in their historical context. The tradition intensified after the Muslim conquest in response to the development of Muslim traditions about Muḥammad’s ascent to the heavens from the site of the Temple. Thus, the same description is found also in the Syriac Vision of Daniel: “Then the New Jerusalem will be built, and Zion will be completely inhabited. The mighty Lord will build Zion, and his holy Christ will shine in Jerusalem. Mighty men will build her walls, and holy angels will complete her towers.”Footnote 32 In commenting on this passage, Henze states that, “in the Syriac Apocalypse of Daniel … no connection is made between the earthly and the New Jerusalem. The Heavenly Jerusalem is not like a model of the Jerusalem of David and Solomon but is the locus of intense angelic activity.” As with other motifs, we find a similar description in the Vision, following other examples of Jewish and Christian apocalypses.

C. The Flight to the Wilderness and “Flexible Time”

Part of the eschatological portrait in several apocalyptic works is a flight into the wilderness from the antichrist. In the Vision of Daniel, there are three flights from the antichrist into the wilderness: 1) The flight of the Ishmaelites from the Son of the Daughter of Levi into the wilderness of Paran (where the biblical Ishmael grew up); 2) the flight of Israel, together with Messiah ben Joseph, into the wilderness from Armilus; 3) the flight of Israel into the wilderness of Judah after the killing of Messiah ben Joseph.

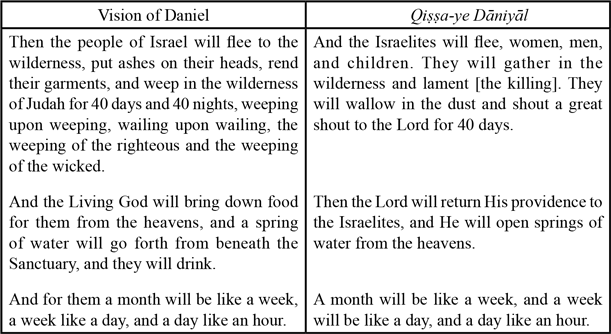

The last flight, into the wilderness of Judah, is unique in that it is specified by a different, flexible time period of forty days and forty nights. They represent a different temporal rhythm. The way that the stay in the wilderness is described is unique to the Vision of Daniel and Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl:

A flight into the wilderness is also mentioned in one of the two aforementioned Syriac apocalypses of Daniel from the seventh century:

All the ends of the earth will be terrified and agitated, and [fear will fall] upon all peoples, nations, and tongues (after Dan 3:31), and upon those who dwell by the seas and those who live in the wilderness, and great fear will fall upon them and trembling will seize them.

Then from the west they will flee to the east, and from the east to the west, and from the north to the south, and from the south to the north. (98, v.26)

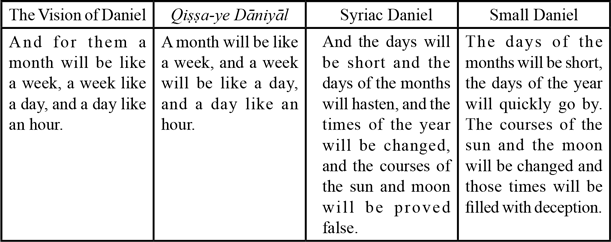

The wilderness is the locus of an interim stay during messianic pangs as well as a target for rebuilding normal civilization in redemption times in all four visions of Daniel. There is, however, a unique calculation of the time, a “Flexible Time,” in these works:

Other apocalypses, like the Book of Elijah, have a tradition about the fixed dates of the future redemption. The Book of Elijah concludes: “Then will come the last day, which is as long as forty days.” Like other time periods in the Book of Elijah, this, too, is a fixed time period, the source of which may be a tradition that relates to the day on which humankind is judged.Footnote 33

The different and unique temporal rhythm of the end of days was already written about in Daniel 9:25–27, where several figures of weeks (7, 62, 1, ½) are mentioned and left for readers to decipher.Footnote 34

“Flexible time,” like “encrypted time,” is a vital component of apocalyptic visions. The damage caused to the faithful upon the dashing of hopes connected to a concrete time can bring about the denial of future redemption. Indicating the possibility that the times of redemption will be “flexible” creates an opening for the hope that the times will not only extend but also be shortened, compressed. “Flexible time” is a moderate expression of the cosmic changes found in eschatological works. Prima facie, its use does not require the upheaval of nature and the world order. Therefore, the redemptive processes can appear suddenly, with an abbreviation of the bad years, like those described in connection with the flight to the wilderness. The description of “return” appears in apocalyptic visions, in the sense of a return to the mythic time after the exodus from Egypt, with all its formative components, including: redemption, lawgiving, and the formation of a people. The joining of “mythic time” with “apocalyptic time” is expected, for in both cases, rules prevail that are different from the rules that govern normal times: They are concrete times with a beginning and end, which entail events; they need not be consecutive or develop according to the normal course of our world. They are dramatic, dangerous times; they contain enchantment and are pregnant with possibility; when such times flow, their heroes are not subject to any temporal influence. Rather, they control time by giving direction to regular events.Footnote 35

In the four visions of Daniel as well, up until the time of redemption, processes unfold within the normal temporal and world order. The “prophesied” events that happened and were still happening, traumatic as they may have been, occurred within a normal natural and temporal framework. It was therefore sufficient for the author to include them as part of the divine plan. Transitional, liminal “flexible time” is deployed for the transition to the eschatological era, the age of redemption. At the beginning of the eschatological era, the mythic figures of messiahs and their enemies become active, and they, too, will perform deeds that conform to the normal functioning of the world order. They will wage large-scale wars and perform great acts of artifice that seem miraculous. The true miracle—the resurrection of the dead—remains to signify the truth of the ultimate redeemer, Messiah ben David.

D. The Conclusion of the Vision

Immediately following the forty days and nights in the wilderness comes the conclusion of the main part of these visions, even though redemption and vengeance are not complete even after the disappearance of the Son of the Daughter of Levi and the killing of Armilus by Messiah ben Joseph. Alongside the extermination of the remaining evildoers, this final redemptive process also lays the (positive) foundation for renewal and rebuilding, including: the resurrection of the dead, the ingathering of the dispersed of Israel, the construction of Jerusalem and the Temple, and the restoration of the prescribed service of God in the Temple. These tasks are assigned, in part, to Messiah ben David. The final sequence of the ultimate salvation is initiated by God, independent of Israel’s cries or conduct.

The conclusion of the Vision seeks to imbue its author, Daniel, with the authority of the vanguard of the new world. It returns to the conclusion in the twelfth chapter of the biblical Book of Daniel and uses its methods and terminology to conceal the time of redemption.Footnote 36 Yet Daniel’s encounter with Jeremiah, Elijah, and Zerubbabel, and his report to Ezra about the salvation of Israel, Messiah ben David, and the secrets of the Vision offer some slight indication about the contents of the lost beginning of the text. Jeremiah, Ezra, and Zerubbabel are mentioned several times at the beginning of Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl. The Judeo-Persian version of the vision opens with Jeremiah: “I am Daniel, of the sons of King Jeconia of Judah, who was in Jerusalem, in the Temple. There was a man with us named Jeremiah ben Hilkiah who was always obedient to the Lord.” Jeremiah is the authority figure who initiates Daniel on his path, just before the destruction of the Temple, just as Ezra and Zerubbabel appear a bit later, after the Jews were permitted to return and rebuild the Temple. Concluding the Vision with Jeremiah, Zerubbabel, and a report to Ezra returns the reader to figures familiar from the beginning of the Vision. Thus, it stands to reason that the Vision of Daniel’s opening was similar to that of Qiṣṣa-ye Dāniyāl.

IV. Concluding Comments

The Vision of Daniel is thus a Hebrew eschatological work composed in the late-ninth century and relating to contemporary events, in an area under Muslim control where the caliphate battled the Byzantine Empire. The work draws from Scriptural, midrashic, and especially apocalyptic Jewish sources but also interfaces with Christian and Muslim theological realms, especially in those parts devoted to enemies of the messiah and the world, which invert and incorporate non-Jewish eschatological images. During the era of the Vision’s composition, several Jewish false messiahs appeared, offering alternative models of Jewish leadership and worldviews that altered the natural and temporal order. The Vision is true to the legacy of tradition both in the behavior it expects from the Jewish public and in the conception of time, it proposes. In its view, the persecutions, crises, and pressures faced by the Jews are part of a larger image of the world that assures ultimate redemption, irrespective of repentance. Miracles—direct divine intervention in wars, ingathering of exiles, the lowering of the Temple, the resurrection of the dead, and the end of death—occur only at the end of the redemptive process; the only condition of the fulfillment of the redemption is loyalty to tradition and commitment to this historical worldview.

V. Appendix: The New Vision of Daniel

MS St. Petersburg National Library, Firkovich Collection, Series A 293 (formerly 22), folios 1a–4a

Pages 1–8: A Collection of Stories and Midrashim

[1a]

1. X. Sulaymān. A great commotion will be in the East and in the West,

2. and the king of Babylon will reign and be a head to the sages,Footnote 37 and the king of the West will die

3. in his days. His reign will last for 10 years: XI. Umar. In his days will be peace

4. in the world and serenity among people. And he will reign 3 years: XII. Yazīd.

5. A wolf of the desert he will be,Footnote 38 robbing people, and then he will die;

6. he will reignFootnote 39 8 years and 2 months. XIII. Then will reign Abu Ḏj̲aʿfar. A great sage

7. with strong opinions he will be; like a wolf, he robs and hoards much gold

8. and silver, leaving nothing for people who seek bread and find none

9. for he will leave nothingFootnote 40 in their hands; they will offer animals for sale

10. but there will be no buyer; he will bury silver vessels in hiding places

11. And he will be revealed to the Ishmaelites in their salvation.Footnote 41 He will be a great sage, a reader

12. of books. He will go to pray at the temple of his mistake[n religion] and die on the way.

13. And his reign will be 22 years, whereupon he will give away his ring so that it will not be left

14. in the hands of the members of his house XVII [XIV?], and those who remain seek, but there is nothing, for

15. he will leave nothing in their hands; they will offer animals for sale, but there will be no

-

16 buyer from the silver vessels in their hands. He will hoard silver and gold and bury it

17. in hiding places; and in the future he will be revealed to people in their salvation

18. and he will be a great sage and a reader of books, and he will ask and seek

19. and demand wisdom; and he will go to celebrate at the temple of his mistake[n religion] and die on the way

20. And his reign will be 22 years, whereupon he will give his ring to the members of his household.

21. After him will reign [XIV] Mahdi his son. He will be wise, and a lover of harlotry

22. he will be; he will profligately spend silver and gold in the world. There will be peace, and falsehood

23. will proliferate in the world. He will go to the land of the East and die there, and his reign

24. will last 10 years: [XV] And after him will reign Musa, his youngest son; he will be fluid

25. of mindFootnote 42 and his desire will be to destroy the world. His reign will be

26. one year and five days. [XVI] And after him will reign Hārūn his son; he will be a roaring lion and a harsh judgeFootnote 43

[1b]

1. who upholds his designsFootnote 44 and kills all the officers of the land and the sons of Ishmael; his desire

2. will be to destroy the world in its entirety, and all his days he will shed blood. He will judge with

3. truth, and he will rove and wander from East to West and from West to East:

4. And he will capture cities and towns from the King of Edom and take a great many captives from them,

5. And he will return to his place in peace. And a man from the East will rise against him and stirFootnote 45 up the

6. whole world against him all day long. He will shed blood,Footnote 46 but not by his own deed [?].Footnote 47 He will call

7. them heretics and pursue the people of the East but not overtake them. He will divide

8. his kingdom in his lifetime among his three sons: Muḥammad in Babylon, the West to Ḳāsim

9. and the East to Ma’mūn: And he will die in exile, and his reign will be 23 years: After him will reign [XVII] Muḥammad

10. his son; he will be wicked in deed but generous, and in his day everybody will earn a living.

11. And in his day tumult and sword will dwell among brothers, and his brother will send against him

12. a great general. He and his sons and brothers will abuse each other and both will kill

13. many soldiers: His spurned brother will come to the country of Babylon and wage war

14. with him. He will kill his brother, loot much, and plunder his treasuries. His reign will be

15. 4 years and 6 months. [XVIII] After him, his brotherFootnote 48 will reign in his place:

16. And after him will reign an officer from his family, Muḥammad by name, and people will change

17. his name. God will bring success to his kingdom, and his enemies will be given in his hands;

18. he will strike and stir up the city of the South, and they will bring him much money from everywhere.

19. And the land will be desolate, and he will die. In his life he will change many things

20. in his kingdom, and he will love building; all his days he will be involved in building: [XIX] After him

21. another king from the East will come with a large force and will reach the country of Babylon.

22. He will capture it and shed much blood. And from there he will go to the West, and against him will

23. stand the He-Goat whose name is Ẓafini/Ẓufyani and they will both do battle,

24. And he will kill the He-Goat, and the Easterner will come to Egypt, and lay

25. it waste. He will shed an inestimable amount of blood therein. And he will turn back

[2a]

1. and come to Damascus and shed blood in it like water. Then the sons of

2. Fāṭima will crown 5 kings: The name of the most senior among them is [XX] Mahdi, and hisFootnote 49 reign

3. will be 3 years. In their days, there will be sword, pestilence, and famine: and they will be erased

4. and pass from the world as though they never were: After all of these,

5. the Daughter of Levi will become pregnant and give birth to a son; his stature will be fifteen cubits

6. higher than the mountains; the Ishmaelites will be killed beforehand, and those who remain

7. will flee to the wilderness of Paran.Footnote 50 The Son of the Daughter of Levi will grow stronger, and all the

8. Northerners along with him. And he will pitch his tent from East to West, which is the country of

9. Babylon. In it they will kill three thousand and a thousand until the waters of the Tigris become

10. dried and turn to blood. Those who come or go will have no respite from the drawn sword,

11. looting, and much plundering: The living will say to the dead, Fortunate are you

12. for you are in graves.Footnote 51 And the Son of the Daughter of Levi will go forth with a large army, and everyone

13. who sees him will flee from before him. And he will have many signs:

14. He will be a hundred cubits tall and ten cubits wide;

15. the length of his noseFootnote 52 will be one cubit. His hair will be long and blond:

16. His eyes will be small,Footnote 53 his teeth long, his beard long,

17. his beard 3 cubits long. Woe and miseryFootnote 54 betides all the people of the world from him

18. and from dread of him. The whole world will say that he is Messiah, but he will not be:

19. And with him will be all Northerners, and the Easterners and Westerners as well, except

20. for the Southerners, who will flee from him; and a remnant of the Ishmaelites

21. will flee with them, and survivors of the sword along with them. And he will spread his net

22. over all the inhabitants of the earth: Then Gog and Magog will hear and come

23. to meet him; their signs are: each of them has four eyes,

24. two in front of them and two behind them, and they pressure the whole world.

25. He chases Israel to destroy them, but the Holy One, blessed be He,Footnote 55 will save them; and He will fight

[2b]

1. them and destroy them: And I, Daniel, upon hearing these words

2. from the mouth of the angel, I shuddered, I spoke rashlyFootnote 56 and said to the angel

3. of God: What will be with my children, my people? He told me: Daniel incline your ear,

4. open your eyes,Footnote 57 and understand all that I speak to you, and all the words

5. I have said to you are truth.Footnote 58 And I further tell

6. you that the offspring of the Female Figure will join with the Son of the Daughter of Levi; his name is Armilus,

7. a son of Belial, bleary-eyed.Footnote 59 He will also speak riddles. They will gather to him—

8. all the wicked men and sons of Belial and a ruthless nation of spillers

9. of blood who permit their wives to one another.Footnote 60 They will say that

10. serving him is greater than serving any of the peoples.Footnote 61 They will go to him,

11. to the West, and believe in him and tell him: You are Messiah.

12. He then calls for fish from the sea, and they emerge and are given to him; he calls for the beast

13. of the field and the bird of the sky and they come to him. They take them

14. and slaughter them. And many of your people will follow him,

15. believing and not believing in the covenant of our God. And people from among the children

16. of Israel who believe in our God’s covenant join.

17. And He will take them—one per town and two per familyFootnote 62 —and lead them to the Holy Place.

18. And the living God will send a righteous man from the children of Ephraim, who will go and gather

19. the sages of Israel and bring them to Armilus the Edomite, the wicked son of Belial,

20. and they will ask him: Are you Messiah?

21. And he will say to them: I am Messiah, and I am your king and your redeemer. They will say

22. to him: We ask for three signs from you. If you tell us,

23. we believe you that you are Messiah. He will say to them:

24. What are the signs that you ask? And they will say: The Staff

25. of Moses, son of Amram, with which he performed signs in Egypt and turned

[3a]

1. the rivers to blood. And he will bring them a staff that resembles the Staff of Moses

2. and it will bud flower and yield almonds. And they will also tell him: Bring us

3. the Jar of Manna, and he will bring it to them. And so will do the righteous Ephraimite

4. and the sages of Israel who will be with him: They will go to the desert and wear sackcloth

5. and sit on the ashes and dress the Torah scroll in sackcloth and sprinkle

6. dustFootnote 63 on their heads and they will come and weep in a loud voice and say: Our God, God of

7. our fathers, God of Abraham, God of Isaac, and God of Jacob: Overlook our stubbornness,

8. our wickedness, and our sins;Footnote 64 and have mercy on us, and hear our prayers and cries

9. and pleas,Footnote 65 and do not deliver us into the hand of this son of Belial. And the Living GodFootnote 66

10. will answer them: My people! Do not fear him, for I will not deliver you

11. into the hand of this son of Belial. Go to him and say to him: Resurrect for us

12. the dead. Immediately, that righteous Ephraimite, together with the righteous of Israel,

13. say to him: Resurrect the dead for us. He immediately becomes angry at

14. the righteous Ephraimite, kills him, and burns him in fire. Then the people of Israel

15. will flee to the wilderness, put ashes on their heads, rend their garments,

16. and weep in the wilderness of Judah for 40 days and 40 nights, weeping upon weeping,

17. wailing upon wailing, the weeping of the righteous and the weeping of the wicked:

18. And the Living God will bring down food for them from the heavens, and a spring

19. of water will go forth from beneath the Sanctuary, and they will drink. And for them a month will be like a week,

20. a week like a day, and a day like an hour: And the Living God will remember Israel

21. and redeem them from the hand of the enemy. The Holy One, blessed be He, will give permission to Messiah,

22. the son of Joseph, so that he may go out and fight with them. He will kill the son of Belial, the son of the Female Figure,

23. and all those nations will gather together and come upon Israel until their roots are

24. uprooted from the land. And those who remain, who did not gather

25. and did not come against Israel will struggle with one anotherFootnote 67 until

[3b]

1. they destroy each other, as it written: “Nation was crushed by nation and city by city,

2. for God stirred them to panic with every kind of trouble:”Footnote 68 And the Living God will remember

3. Israel, and a great darkness will come upon those who remain of the nations that will fall by the sword

4. and He will shine a light upon Israel as He didFootnote 69 for them in Egypt. And the Holy One, blessed be He,

5. will watch over them from the heavens and have mercy on them; He will stand on the Mount of Olives

6. and the mountain will split in dread of Him.Footnote 70 And the scion of Jesse will be on His right and Zerubbabel, son of Shealtiel

7. to His left, and Elijah the Prophet with them. And the son of Jesse will burn all the wicked ones

8. with the breath of his lips,Footnote 71 and he will cast their carcass to the earth, where the fowl of the sky will eat them,

9. as will the beast of the earth. And for seven years the Israelites will not need wood for kindling

10. in their ovens, for they will burn stakes of broom shrubs from the peoples:Footnote 72

11. And Zerubbabel, son of Shealtiel, will blow a great shofar and gather

12. all of My people, Israel, from the four corners of the earth. And the son of Jesse will wake

13. those who dwell in the dust. He will go forth from below the Mount of Olives, and the righteous among them

14. will be carried on wings of eagles, and the remaining saints

15. on the clouds of heaven: And the Living God will lower Jerusalem.

16. And God will lower Jerusalem, already built, from heaven, with chains of iron,

17. and He will set it upon four [mountains]: Tabor, Carmel, Hermon, and the Mount

18. of Olives: [And the heavens] and the earth will be renewed,Footnote 73 and they will build Jerusalem with precious stones

19. and gems, and they will bring Israel up [to Jerusalem] with acclaim, rejoicing, song, and praise:

20. And Abraham will sit on the right [of the son of Jesse], and Moses will sit to the left,

21. and they will all enter Jerusalem joyfully, and they will say to Moses: Look! This

22. is your people, the flock you pastured! And Abraham and Moses will walk before you,

23. and the Living God will bring down the manna for them, as of yore: Death will be swallowed up

24. forever. And Messiah, the son of David, will arise after all the wars of Messiah,

25. son of Joseph; he will appear as a king, and he will draw out the Leviathan with a hook and raise it

[4a]

1. from the sea. And the Behemoths that he pastures on a thousand mountains, Messiah will slaughter

2. all three of them severely (?).Footnote 74 And they will eat and rejoice a great joy,

3. unlike any other that has been made from the day the world was created

4. until this day. They will bow and give praise to their Creator with thanks,

5. with songs, and with ecstasy. High Priests and Levites will sing,

6. Aaron the High Priest and the Priests will offer sacrifices and slaughter them,

7. for all time (?): And I, Daniel, upon hearing these words,

8. rejoiced greatly; I honored, extolled, and praised

9. the Supreme King of kings,Footnote 75 and I said to the angel: When will these visions

10. [be fulfilled]? He told me: Lie with your forefathers and arise to accept your fate

11. at the end of days.Footnote 76 Thereupon Jeremiah and Elijah and Zerubbabel, son of Shealtiel, came to me

12. and said: Write down this vision. I revealed it to Ezra

13. the Scribe, and it uplifted me; and I revealed the redemption of Israel, and about the scion,

14. the son of [Jesse],Footnote 77 so that [Ezra] reveals these secretsFootnote 78 to the sages, for it will remain hidden until

15. the time of Israel’s salvation. Written and sealed.