Most theories claim that extreme right parties cannot win in post-Second World War Europe (e.g. Art Reference Art2011; Carter Reference Carter2005; Hainsworth Reference Hainsworth2008). Fascist ideas associated with the authoritarian regimes of inter-war Europe are largely discredited because of their violence, authoritarianism and opposition to democracy. The far right parties that have experienced electoral support in post-war Europe tend to be those that have disassociated themselves from fascism and racist violence (see e.g. Golder Reference Golder2003; Halkiopoulou et al. Reference Halikiopoulou, Mock and Vasilopoulou2013). However, in the context of the eurozone crisis that erupted after 2009, the previously marginalized neo-Nazi Greek Golden Dawn marked its electoral breakthrough in May 2012 when it gained 21 seats in a parliament of 300. This trend continued in the 2014 European Parliament (EP) elections and the January and September 2015 national elections. This indicates consistent Golden Dawn support despite the fact that its leading members were imprisoned at the time of the election, facing indictment, and the party did little campaigning.

The Golden Dawn is an extreme right party that may be described as a fascist or neo-Nazi group. This differentiates the party from other far right populist parties that have been successful in other Western European countries since the 1980s, both in terms of degree and in terms of kind. Not only does the Golden Dawn employ violence to pursue its extreme right ideological agenda, but most importantly this ideological agenda is premised on an alternative vision of democracy modelled on the principles of National Socialism.

If we were to attribute the rise of the Golden Dawn to the economic crisis, then this begs the question of why extreme right parties have not been successful in other countries which have experienced comparable crisis conditions and severe economic breakdown, including Portugal and Spain. In these countries recent elections have shown no increase in support for the already marginalized extreme right National Renovator Party (PNR), Spain 2000 and National Democracy (DN). This article addresses this variation through a controlled comparison (Doner et al. Reference Doner, Ritchie and Slater2005; Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013) of Greece, Portugal and Spain. We compare three cases which share a number of economic, political and cultural similarities but are exhibiting a variation in the dependent variable. This enables us to control for various explanations provided in the literature that may be held constant across our cases.

Our comparison of Greece, Portugal and Spain indicates that it is the nature rather than the intensity of the crisis that increases the likelihood of the rise of the extreme right at times of economic hardship. We argue that extreme right parties are more likely to experience an increase in their support when economic crisis culminates in an overall crisis of democratic representation. Economic crisis is likely to become a political crisis when severe issues of governability affect the ability of the state to fulfil its social contract obligations. This breach of the social contract is accompanied by declining levels of trust in state institutions, resulting in party system collapse. In these circumstances citizens may question the existing mechanisms of democratic representation, which opens space for parties that are anti-systemic and offer an alternative vision of representation.

If our argument is correct, economic crisis in itself is not enough to facilitate the rise of extreme right parties. This outcome is only likely if economic crisis is accompanied by severe problems of governability, resulting in a crisis of democratic representation. This article proceeds as follows. First, we contextualize the ‘puzzle’, focusing on the variation of extreme right party support in crisis-ridden Greece, Portugal and Spain. Second, we carry out a controlled comparison of the three countries. We show that Greece, Portugal and Spain share a number of demand- and supply-side conditions, including similar economic crisis dynamics, electoral systems, party competition dynamics, highly conservative right-wing competitors, history of right-wing authoritarianism and a fragmentation of the right, eliminating these variables as potential causal explanations. Third, we posit an argument that goes beyond these explanations and focuses on democratic representation and party system collapse. We conclude with a discussion of our argument’s theoretical contribution and avenues for future research.

The Extreme Right Puzzle

How may we define and understand the extreme right? This article places the extreme right within the overall umbrella term ‘far right’, which encompasses both radical and extreme right variants. The far right refers to a broad range of political parties and social groups whose common core ideological feature is nationalism (Eatwell Reference Eatwell2000; Hainsworth Reference Hainsworth2008) – that is, a strict definition of the boundaries between the native group and the other and an emphasis on maintaining the homogeneity of the nation (Smith Reference Smith1991). Within this umbrella, we may distinguish between the radical and the extreme right. The radical right designates the ‘new’ parties that have emerged in Europe (Ignazi Reference Ignazi1995) since the 1980s. These parties have adopted a modernized discourse that abandons outright references to race and claims a distance from fascism (Halikiopoulou et al. Reference Halikiopoulou, Mock and Vasilopoulou2013). They are characterized by a populist rhetoric that differentiates between the ‘good people’ and the ‘corrupt elite’. The extreme right, on the other hand, designates parties and groups which have not distanced themselves from fascism; they tend to advocate a large state and employ violence in their tactics in an attempt to cleanse the homogeneous nation from internal and external enemies. The extreme right may be defined as the antithesis of democracy (Mudde Reference Mudde2010): a rejection of procedural democracy and the idea that popular sovereignty may be exercised in accordance with electoral principles. While the extreme right variants are also populist, their use of this concept differs in their ideology and agenda. They understand themselves primarily as movements from below that embody the will of the people rather than represent or speak on its behalf.

Theories of the far right postulate that in general terms extreme right parties are not electorally successful (e.g. Betz Reference Betz1998; Kitschelt with McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995) in post-war Europe. The success of a far right party is inversely related to its proximity to fascism. The association of fascist ideals with totalitarianism, mass violence, racial extermination and an all-encompassing state has questioned the legitimacy of these parties. In essence fascism rejects liberal representative democracy and ultimately seeks regime change. Since the 1980s, the far right parties that have been electorally successful are those that operate within the confines of liberal democracy and seek change from within. While also nationalist, these parties define ‘otherness’ not in strict racial terms but rather through ideological criteria (Halikiopoulou et al. Reference Halikiopoulou, Mock and Vasilopoulou2013). Exclusion is not justified on bloodline or birth traits, but rather on worldviews and systems of belief. Parties that have enjoyed electoral support in their respective countries, such as the Swiss People’s Party, the Dutch Party for Freedom and the True Finns, reject the fascist label, have been careful to disassociate themselves from such ideals and have centred their discourse on a rhetoric of toleration: excluding not those who are different by birth but those who because of their ideological beliefs are intolerant of the ideals of ‘our’ nation.

If we accept this premise, the dramatic rise of the Greek Golden Dawn constitutes an anomaly. Other far right parties have enjoyed electoral success in Greece, for example the Popular Orthodox Rally (LAOS) and Independent Greeks (ANEL). However, these fall within the radical right category (Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou Reference Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou2015) and their support is more consistent with the predictions of existing theories. By contrast, the Golden Dawn falls into the extreme right category. This is an ultra-nationalist and racist party that most resembles traditional Nazism both in terms of degree and in terms of kind: in its espousal of what Mann (Reference Mann2004) identifies as defining criteria of a fascist group, including nationalism, statism, paramilitarism, transcendence and cleansing. The party’s ideology emphasizes the principles of National Socialism. It opposes democracy on a number of grounds, for example that it cannot be applied in practice, that it was not actually approved by the Ancient Greeks and that it gives power to any layman, who may not endorse nationalist ideals (Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou Reference Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou2015). The party’s organizational structures also resemble those of the Nazi system, stressing violence, discipline and ultimate respect for the leader. Although it was openly extreme, the party received support from over 400,000 Greek citizens during the May and June 2012 national elections, when it received 6.97 and 6.92 per cent of the votes cast respectively, gaining 21 and 18 parliamentary seats out of 300. It sustained its electoral base in the May 2014 European Parliament elections, receiving 9.39 per cent of the vote and gaining three seats in the European Parliament. While in the January 2015 general election support for the party dropped, the Golden Dawn still managed to attract 6.28 per cent of the votes cast, occupying third place in the Greek Parliament with 17 seats. The party increased this percentage slightly in September 2015, receiving 6.99 per cent of the votes cast and increasing its number of seats to 18. Within the context of the imprisonment and pending indictment of its leading members, this is a significant result in itself and indicates that the Golden Dawn accommodates a substantial percentage of Greek voters. It is notable that the party did not even participate in the election campaigns.

This might urge us to attribute the electoral rise and persistence of the Golden Dawn to economic crisis and draw parallels with other countries that have experienced comparable crisis conditions. But this begs the question: why have extreme right parties in Spain and Portugal remained marginalized? In Portugal, the extreme right National Renovator Party received 0.2 per cent of the votes cast in 2009, which it raised marginally to 0.3 per cent in 2011, indicating static and low levels of support. In Spain this was the case for Spain 2000 – which although active in organizing various community services such as soup kitchens which, modelled on the Nazi winterhilfswerk, are also used by the Golden Dawn – and National Democracy, which despite its strong anti-immigrant agenda actually lost support (see Table 1).

Table 1 Percentage of the Vote Received by the Extreme Right in Greece, Portugal and Spain

Note: DN=National Democracy; EP=European Parliament; PNR=National Renovator Party.

These parties are comparable to the Golden Dawn in terms of their ideology, organization and rejection of parliamentary democracy. They have a similar nationalist agenda emphasizing anti-immigration premised on the need to maintain the homogeneity of the nation and a return to traditional values. The Portuguese National Renovator Party celebrates ‘Salazar as the greatest twentieth-century Portuguese statesman’ (Marchi Reference Marchi2013: 139). The party has been unsuccessful in its attempts to modernize, remaining in what scholars categorize as the ‘old’ extreme right. Similarly Spain 2000 and National Democracy may be termed neo-Francoist or neo-fascist. Although these parties have attempted to put forward a more moderate image and attract mostly conservative right-wing voters, they ‘keep alive the historical memory of Spanish fascism, the Civil War and the Franco regime’ (Rodriguez Jiménez Reference Rodríguez Jiménez2012: 117).

This variation brings us back to our central questions: Why has an extreme right party with clear links to fascism experienced such a rise in Greece, defying all theories that claim that a neo-Nazi party is unlikely to win in post-Second World War Europe? And, if we accept that economic crisis is an explanation for this, why has such a phenomenon not occurred in other countries that have similar conducive conditions, such as Portugal and Spain?

Comparing Greece, Portugal and Spain

This article employs the most similar systems research design (Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013) in order to identify the conditions which have facilitated the rise of an extreme right party in Greece but not in Portugal and Spain. These countries share a number of political, cultural and economic similarities that allow for a meaningful comparison (Hartlapp and Leiber Reference Hartlapp and Leiber2010; Zartaloudis Reference Zartaloudis2013). In terms of their political landscapes, Greece, Portugal and Spain are all characterized by a strong left–right divide and have experienced civil war and right-wing authoritarianism in their recent histories. All three became democracies during the third wave of democratization and joined the EU in the 1980s. They are all European peripheral countries with similar levels of socioeconomic development and were the main beneficiaries of the EU’s structural and cohesion funds prior to the eastern enlargement of the EU. These countries have been affected by the eurozone crisis more than any other eurozone members. They were identified as the three most at-risk European economies during the European sovereign debt crisis, they all received external financial assistance and experienced severe austerity measures and public sector cuts. Yet only Greece has experienced the rise of an extreme right party. Taking this variation into account, this article is concerned with the comparative dimension of extreme right party support.

The second step in carrying out a meaningful comparison is to identify potential explanatory variables, as discussed in the literature. Scholars have identified a number of factors as possible explanations for the rise of the far right understood in the broad, umbrella sense. These may be categorized in terms of demand (Bell Reference Bell1964; Golder Reference Golder2003; Lipset Reference Lipset1960; Ramet Reference Ramet1999) and supply (Mudde Reference Mudde2010; Norris Reference Norris2005). Demand-side explanations postulate that ‘“structurally determined pathologies” triggered by “extreme conditions” (i.e. crises)’ result in the rise of far right parties (Mudde Reference Mudde2010: 1171). Such parties ‘appeal to the disgruntled and the psychologically homeless, to the personal failures, the socially isolated, the economically insecure, the uneducated, unsophisticated, and authoritarian persons at every level of the society’ (Lipset Reference Lipset1960: 173). External triggers such as economic crises, globalization and other societal changes create societies of winners and losers in which the dispossessed and unemployed will express their protest by opting for a far right party (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). Far right parties are able to capitalize on the insecurities of downward social mobility. For example, the inter-war economic crisis and the wide social discontent it generated have been closely linked with the rise of Nazism and fascism in Europe (Lipset Reference Lipset1960). Supply-side explanations focus on the opportunities and constraints offered by the political-institutional context within which parties operate. The existence of political space for far right parties may depend upon the electoral system (Carter Reference Carter2002); party competition (Mudde Reference Mudde2007), the presence of a mainstream right-wing competitor and its ability to absorb far right voters (Chhibber and Torcal Reference Chhibber and Torcal1997; Ellwood Reference Ellwood1995), and the fragmentation of the right into various factions that are unwilling to coalesce (Marchi Reference Marchi2013).

We proceed by applying each of these explanations to the context of Greece, Portugal and Spain. The logic of comparison eliminates a number of the above demand- and supply-side variables as causal explanations. Our first step is to compare certain demand-side indicators relevant to the eurozone crisis as the external trigger, given that all three countries have experienced the worst of the crisis. We compare Greece, Portugal and Spain against a number of ‘misery indicators’ (Pappas and O’Malley Reference Pappas and O’Malley2014). These include government deficit as percentage of GDP across the eurozone, levels of unemployment and youth unemployment as well as real GDP growth rate to measure recession. We define recession in terms of two consecutive quarters of negative growth (Keely and Love Reference Keely and Love2010). Our three cases have the highest rates of government deficit as percentage of GDP across the eurozone. In 2009 with the onset of the crisis, Greece had a government deficit of −15.2, Portugal had −9.8 and Spain −10.9. This similar trend of high government deficit continued up to 2013. Unemployment rates are also very high and dramatically increased since the onset of the crisis in all three countries. Similarly youth unemployment is particularly high across all three countries and well above the EU average. Measuring the dynamics of economic development, real GDP growth rate shows a similar picture: economic recession over consecutive years among all three countries (see Table 2). This indicates that economic indicators alone are not enough to explain the variation in extreme right party support across the three cases.

Table 2 Economic Indicators

The logic of comparison also eliminates a number of supply-side variables. First, we examine the electoral system. Because proportional electoral systems tend to favour representation of smaller parties, we might expect electoral system variation to play a role in the success of far right parties (Alonso and Kaltwasser Reference Alonso and Kaltwasser2015; Norris Reference Norris2005). Greece, Portugal and Spain, however, all have similar electoral systems. They all adopt a list-proportional electoral system, either closed or open. Despite this proportional element, all three adopt the D’Hondt formula, which favours large parties; in Greece and Spain the electoral system tends to have a majoritarian effect, creating a party system where power tends to alternate between two main competitors (Freire Reference Freire2005; Hopkin Reference Hopkin2005; Pappas Reference Pappas2003). The majoritarian effect is less prevalent in Portugal. The same pattern holds for European Parliament election results, where the electoral system is even more standardized across cases (Hix and Hagemann Reference Hix and Hagemann2009). Despite having a closed ballot structure and large district magnitude, the three countries show a variation in extreme right party support.

This is consistent with a number of theories that have found that the electoral system is not necessarily causally related to the rise of far right parties (Arzheimer and Carter 2006; Carter Reference Carter2005; Van der Brug et al. Reference Van der Brug, Fennema and Tillie2005). Therefore it makes sense to proceed by examining a related issue – party system dynamics prior to the eurozone crisis. Theories posit that multiparty systems are more conducive to far right party success than two-party systems or systems characterized by bipolarity. All three cases exhibit bipolarity in their party system dynamics. Two mainstream parties, a centre-left and a centre-right, are the most relevant actors and have tended to alternate in power. In Greece the centre-right New Democracy and the centre-left Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), which, until 2012, together occupied the vast majority of the 300 parliamentary seats (Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou Reference Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou2013), have dominated the political scene in the post-dictatorship era. In Portugal, competition takes place primarily between the centre-left Socialist Party (PS) and the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSD), often in coalition with the right-wing CDS-People’s Party, which have constituted the main political actors in the system (Freire Reference Freire2005). And in Spain, the state-wide vote has been concentrated around the centre-right People’s Party (PP) and the centre-left Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) (Hopkin Reference Hopkin2005).

The logic of comparison illustrates that it is also problematic to attribute the low support for far right parties in Portugal and Spain to the existence of a mainstream right-wing competitor able to appropriate potential demand for far right ideas (Ellwood Reference Ellwood1995; Chhibber and Torcal Reference Chhibber and Torcal1997). This is because the presence of a highly conservative mainstream competitor is constant across our cases: all three have a strong centre-right party or bloc which could absorb such voters (see Table 3). The Greek New Democracy, the Portuguese CDS-People’s Party and the Spanish People’s Party all score very highly on various dimensions that capture traditional authoritarian party positions (the GAL/TAN dimension) (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015), including law and order, social lifestyle, religious principles in politics, immigration policy, integration of immigrants and asylum seekers, nationalism and position towards ethnic minorities. While the Portuguese Social Democratic Party scores lower compared with the Greek New Democracy and Spanish People’s Party, the more authoritarian space is occupied by the CDS-People’s Party, which often runs jointly with the Social Democratic Party.

Table 3 Party Positions on the GAL/TAN Dimension

Source: Chapel Hill Expert Survey 2010 (Bakker et al. Reference Bakker, de Vries, Edwards, Hooghe, Jolly, Marks, Polk, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2015).

In addition, Greece, Portugal and Spain share a legacy of right-wing authoritarianism, so if we make the claim that the right is discredited because of its historical association with right-wing authoritarianism, this should be true across all three. Greece experienced right-wing authoritarianism during the Metaxas dictatorship (1936–41) and the Colonels’ junta (1967–74); Portugal during the 1926–33 military dictatorship, followed by the Estado Novo period (1933–74); and Spain during the restoration period under Primo de Rivera (1923–30) and the Franco regime (1939–75).

Equally problematic is the attempt to attribute the lack of support for extreme right parties in Spain and Portugal to the fragmentation of the right. If one of the reasons that Portugal and Spain have not experienced a rise in extreme right parties is the unwillingness of the various extreme right-wing factions to coalesce (Alonso and Kaltwasser Reference Alonso and Kaltwasser2015; Marchi Reference Marchi2013: 133), then we should expect the fragmentation of the right to have similar effects in Greece. However, a number of extreme right parties have competed for elections since the 1980s, including Front Line, the Hellenism Party, the Hellenic Front, the National Coalition, the Patriotic Alliance and the Golden Dawn.

In short, we have shown that Greece, Portugal and Spain share a number of demand- and supply-side conditions, including similar economic dynamics, electoral systems, party competition dynamics, highly conservative right-wing competitors, a history of right-wing authoritarianism and a fragmentation of the right. Therefore our comparison illustrates that these variables fall short of accounting for the variation in extreme right party support across the three cases. This does not necessarily mean that demand- and supply-side dynamics are irrelevant to the variation, but rather that we need to nuance and reconceptualize the theory of interdependence between demand and supply through a different prism: the broader implications of economic crisis in the institutional, political and democratic spheres. We proceed to construct our argument below (see Table 4).

Table 4 Demand- and Supply-side Variables

The Rise of the Extreme Right: A Crisis of Democratic Representation

We argue that extreme right parties are more likely to experience an increase in their support when economic crisis culminates in a crisis of democratic representation. Our logic is as follows: economic crisis is likely to become a political crisis when there are severe issues of governability. In turn this may acquire an ideological dimension when the state is less able to mediate the effects of the crisis and fulfil its social contract obligations. This challenges not simply the legitimacy of individual parties but also the legitimacy of the system itself. This results in low levels of trust in state institutions, undermining the social basis of the main competitors in the system (Morgan Reference Morgan2011). Large parts of society protest against their perceived inability to influence decision-making and hold politicians accountable. The dominance of the old established parties is challenged, resulting in party system collapse as ‘citizens do not believe that representatives are acting on behalf of their constituents or of some vision of a public good’ (Mainwaring et al. Reference Mainwaring, Bejarano and Pizarro Leongomez2006: 15). In these circumstances citizens question the existing mechanisms of democratic representation, which opens space for parties that are anti-systemic and offer an alternative vision of representation. These parties on the margins of the system offer this alternative vision while at the same time – precisely because of their fringe status – remaining disassociated from the ‘old discredited’ system. Therefore, economic crisis is not by itself sufficient to facilitate the rise of an extreme right party. This is not a question of intensity of economic crisis. Rather it is the nature of the crisis – economic versus overall crisis of democratic representation – that facilitates the rise of the extreme right.

In order to illustrate our argument we draw on literature on democratic representation and party system collapse (Mainwaring et al. Reference Mainwaring, Bejarano and Pizarro Leongomez2006; Mann Reference Mann2004; Seawright Reference Seawright2012; Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou Reference Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou2015). The starting point is the extent to which economic crisis is accompanied by problems of governability, thus acquiring a political dimension. Perceptions of state capacity are the link between political crisis and ideological crisis. This refers to the perceived inability of the state to mediate the effects of the crisis and to deliver services based on the redistribution of the collective goods of the state (Slater et al. Reference Slater, Smith and Nair2014). Thus the political and ideological dimensions of the crisis are the defining factors: the strength of democratic institutions (Pappas Reference Pappas2013), state capacity (Slater et al. Reference Slater, Smith and Nair2014) and the ability of the state to meet its social contract obligations (Wimmer Reference Wimmer1997) and to continue the provision of basic services and redistribution (Pappas and O’Malley Reference Pappas and O’Malley2014). When state capacity is limited or perceived to be limited, the result is the delegitimization of the party system as a whole. This is because the system is perceived as incapable of addressing the crisis and mediating its socioeconomic effects. The result is low levels of trust and party system collapse. One of the major differences between Greece, Portugal and Spain is the extent to which the crisis triggered the breakdown of the political system itself because of the perceived limited ability of the state to address the crisis. In Portugal and Spain, the state was perceived as better able to limit the socioeconomic impact of the crisis on individual citizens.

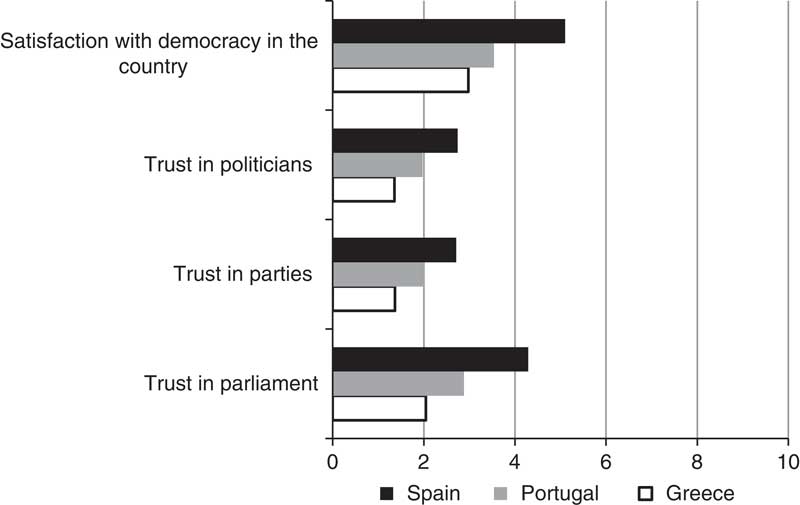

We may measure this through the use of a number of indicators that measure trust, good governance and the perceived efficacy of the state (Kopecky et al. Reference Kopecky, Mair and Spirova2012; Transparency International 2011; World Bank 2012). Trust in institutions may include measuring trust in the national parliament, trust in political parties and trust in politicians. An examination of these indicators illustrates that Greece scores very poorly both in stand-alone terms and compared with Portugal and Spain. We measure trust in institutions and satisfaction with democracy through citizens’ responses in the European Social Survey. We choose to report citizens’ responses for the 2010 wave because it is the most recent study that includes all three countries since the outbreak of the crisis. While there is a general trend in Europe of low levels of trust in institutions and low satisfaction with democracy, on average Greece scores much lower than Portugal and Spain (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Average Trust in Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy Source: European Social Survey (2010).

Governance refers to the ability of institutions to control their societies (Peters Reference Peters1995). The World Bank (1992: 1) defines governance as ‘the manner in which power is exercised in the management of a country’s economic and social resources for development’. Good governance is expected to increase satisfaction and trust. Thus such indicators tend to be used as proxies for good governance (Kaufmann et al. Reference Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi2010). Failing performance of the state may be measured with: (1) perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality and impartiality of the civil service, and the credibility of the government in terms of policy formulation and implementation (government effectiveness); (2) the ability of the government to regulate the private sector (regulatory quality); (3) confidence in the rules of society, in particular the quality of contract enforcement (rule of law); and (4) the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain (control of corruption/corruption perceptions index). In terms of these state performance and perceptions of quality of state services, Greece also ranks poorly compared with the other two cases and showed a notable decline in its governance score – i.e. the estimate of governance measured on a scale from approximately −2.5 to +2.5, between 2004 and 2014 (see Table 5).

Table 5 Performance of Greece, Portugal and Spain on Good Governance Indicators

Sources: World Bank (2015).

Note: Estimate of governance measured on a scale from approximately −2.5 to +2.5. Higher values correspond to better governance.

Failing performance may also be measured in terms of party patronage and clientelism (Afonso et al. Reference Afonso, Zartaloudis and Papadopoulos2015) and the extent to which political parties are able to exercise direction over appointments within state institutions (party patronage index). Party patronage tends to be understood as a ‘form of linkage politics’ whereby parties and/or politicians (patrons) distribute benefits to voters (clients) in exchange for electoral support. Kopecky et al.’s (Reference Kopecky, Mair and Spirova2012) conception of patronage as an organizational resource instead focuses on the ability of parties to build organizational networks and distribute jobs within the state, thus obtaining institutional control of the latter. In accordance with the Corruption Perceptions Index constructed by Transparency International (2011), which ranks countries on a scale of 0 to 10 where 0 means that a country is perceived as highly corrupt and 10 means that a country is perceived as very clean, the contrast is sharp. Greece is ranked 80th with a score of 3.4 on the corruption scale, while Portugal is ranked 32nd with a score of 6.1 and Spain 31st with a score of 6.2. On Kopecky et al.’s (Reference Kopecky, Mair and Spirova2012) index of party patronage, Greece is by far the highest of our three countries and above the EU average at 0.62, whereas Portugal and Spain score much lower at 0.29 and 0.40 respectively. This is significant in light of the dynamics of the Greek political system, which is traditionally based on patronage and clientelism (Mitsopoulos and Pelagides Reference Mitsopoulos and Pelagidis2011; Pappas Reference Pappas2003). In this case, Greece constitutes the paradox vis-à-vis Portugal and Spain given its ability to sustain a democratic institutional system during the post-dictatorship era ‘while not progressing beyond the entrenched and deeply embedded clientelistic and rent-seeking networks that permeate Greek political culture’ (Vasilopoulou et al. Reference Vasilopoulou and Exadaktylos2014). The crisis challenged this clientelistic system at its core, discrediting the main actors and resulting in low levels of trust in democratic institutions.

Low levels of trust, the weakness of the state and its perceived lack of efficacy to moderate the effects of the crisis resulted in a crisis of representation which brought about the collapse of the party system in Greece, whereas in the other two cases this did not take place. The Greek May and June 2012 elections were characterized by the highest levels of volatility since the restoration of democracy in 1974. Not only did the elections result in the implosion of the incumbent PASOK which received a mere 33 seats compared with the 160 seats it had received in 2009; but the main opposition party also suffered great losses and the Coalition of the Radical Left (SYRIZA), a radical party with an agenda opposing the austerity measures agreed with the EU, formerly on the fringes of the party system, emerged as the main contender. Beyond punishing the incumbent, Greek voters punished the two main parties, which were perceived as the main source of the inefficiency and corrupt nature of the system, indicating that the two main contenders had lost their social base (Verney Reference Verney2014).

This trend was sustained during the 2014 European Parliament elections and the January and September 2015 national elections, which both resulted in SYRIZA becoming the leading party in parliament and the Golden Dawn third. The result was the emergence of a new cleavage in Greece, expressed through strong support for anti-systemic and anti-memorandum parties (Dinas and Rori Reference Dinas and Rori2013; Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou Reference Vasilopoulou and Halikiopoulou2013). In other words, the crisis of political representation opened up a space for parties beyond the confines of the system – parties that offered an alternative vision of representation and more broadly an alternative solution to the crisis – such as the Golden Dawn.

Because levels of trust, state capacity and perceptions about the efficacy of the state to handle the crisis were higher in Portugal and Spain, the crisis did not result in a crisis of democratic representation. In those two countries, voters blamed the incumbent party for its inability to manage the economy. This, however, did not translate into the implosion of the incumbent, nor in a major restructuring of the party system itself (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2011; Martín and Urquizu-Sancho Reference Martín and Urquizu-Sancho2012). Electoral competition took place along familiar divisions with no emergence of systemic/anti-systemic or pro-austerity/anti-austerity divisions. While in Spain new parties did enter the system, overall competition dynamics did not change dramatically, and in both cases resulted in the main opposition party emerging as the winner.

In Portugal, party dynamics remained broadly similar to previous years. In 2011, elections resulted in a clear victory for the centre-right Social Democratic Party, gaining approximately 10 per cent. The party received 105 seats while the centre-left Socialist Party received 73 seats, compared with 78 and 96 in 2009 and 72 and 120 in 2005 respectively. Anti-system parties were not able to capitalize on the crisis; in fact, ‘in absolute terms, the PCP [Portuguese Communist Party] lost 6,000 votes and the BE [Left Bloc] lost almost half of its electoral base’ (Fernandes Reference Fernandes2011: 1300). Classic dynamics of alternation between the two main contenders in the system continued during the 2014 European Parliament elections, in which the Socialist Party came first.Footnote 1

Similarly in the 2011 Spanish national elections voters punished the incumbent centre-left Socialist Workers’ Party, instead granting the mandate to govern to its main centre-right opposition party, the People’s Party. The Socialist Workers’ Party suffered a sharp electoral decline, losing a large number of seats. It received 110 seats in 2011, compared with 169 in 2008, lowering its support from 43.9 per cent to 28.8 per cent. But unlike in Greece, no fundamental restructuring or collapse of the party system took place in Spain. Competition remained concentrated around the centre-right People’s Party and the centre-left Socialist Workers’ Party, while the latter still remains a potent contender, unlike the Greek PASOK, which became replaced by SYRIZA as the main opposition party. In Spain the campaign focused on competence in handling economic issues and overall it was of low intensity (Martín and Urquizu-Sancho Reference Martín and Urquizu-Sancho2012). This trend continued during the 2014 European Parliament elections, where the People’s Party came first. During these elections both the People’s Party and the Socialist Workers’ Party lost some of their vote share, while a new contender, the far left PODEMOS came fourth with 7.98 per cent. The impending 2015 national elections in Spain are expected to produce a level of fractionalization in the party system and an increase in support for small parties, including PODEMOS and Ciudadanos. However, neither of these two parties is extreme. Although critical of the status quo, these parties operate within the existing system of representation rather than putting forward an alternative vision altogether.

Conclusion

Why has an extreme right party with clear links to fascism experienced a rise in Greece, defying all theories that claim that such a party is unlikely to win in post-Second World War Europe? And, if we accept that economic crisis is an explanation for this, why has such a phenomenon not occurred in other countries that have similar conducive conditions, such as Portugal and Spain? This article has addressed this puzzle by: (1) eliminating potential explanatory variables through a systematic comparison of Greece, Portugal and Spain; and (2) showing that the rise of the extreme right is not a question of intensity of economic crisis. Rather it is the nature of the crisis – that is, economic versus overall crisis of democratic representation – that facilitates the rise of the extreme right.

Our argument centres on the impact of economic crisis on democratic representation. Economic crisis is likely to have a political dimension when severe issues of governability impact upon the ability of the state to mediate the effects of economic hardship. This breach of the social contract is accompanied by declining levels of trust in state institutions, resulting in party system collapse. In these circumstances citizens may question the existing mechanisms of democratic representation, which create a space for parties that are anti-systemic and offer an alternative vision of representation. In Portugal and Spain, on the one hand, the economic crisis did not result in an overall crisis of democratic representation. Rather than party system collapse, the incumbent political parties bore the political responsibility for the crisis in a typical power alternation fashion. In Greece, on the other hand, the economic crisis led to a major discrediting of the two main actors in the system and the delegitimization of the system itself, altering party system dynamics and opening up space for smaller parties that offered an alternative vision of democratic representation.

Our theoretical contribution is twofold. First, we build on existing literature which argues that economic crisis will not necessarily lead to the rise of extreme right parties (Art Reference Art2011; Mudde Reference Mudde2007), and we illustrate that in fact it is the rarest outcome. We arrive at this conclusion through a comparative logic. An interpretation of the increase in support for the Golden Dawn as a direct product of the eurozone crisis would constitute a fallacy resulting from an endeavour to study Greece as an outlier or a single case study. Such an approach lacks the potential to control for alternative explanations and to construct a theory of extreme right party support at times of crisis that will have applicability beyond one particular case study. Our controlled comparison establishes that institutional factors such as electoral system, party competition, highly conservative right-wing competitors and the fragmentation of the right – treated in most of the literature as explanatory variables – do not explain the rise of extreme right parties at times of crisis.

Second, we show that what allowed the emergence of the anti-systemic Golden Dawn in Greece was not the economic crisis per se, but rather its political dimension, the perceived inability of the state to mediate the crisis, resulting in a crisis of democratic representation. By taking into account issues of governability, perceptions of state capacity and the extent to which an economic crisis becomes translated into a political crisis with systemic consequences (Mann Reference Mann2004; Slater et al. Reference Slater, Smith and Nair2014), we apply theories that focus on democratic representation and party system collapse in other regional contexts. In doing so we differentiate the rise of the Golden Dawn in Greece from the general phenomenon of the rise of far right populism in Western Europe during times of affluence and economic stability.

Greece, Portugal and Spain have offered us an ideal platform upon which to test the impact of economic crisis on extreme right party support. We have not included Ireland in our comparison. Despite having experienced similar crisis conditions, Ireland is dissimilar to Greece, Portugal and Spain in terms of a number of historical, political and institutional variables, and could thus skew our controlled comparison. The Irish party system is not defined by a left–right cleavage. Unlike parties in other European countries, Irish parties are not directly linked to a specific class. Fianna Fail and Fine Gail have been divided on a number of historical and identity issues, including religion, the Irish civil war, and between 1969 and 1986 the question of Northern Ireland. The country has not experienced right-wing authoritarianism and has never witnessed the considerable political presence of an extreme right party. Hence we have confined our universe of cases to three countries that share a number of similarities that could be potentially causal, thus allowing for a controlled comparison.

These important similarities have allowed us to control for – and therefore eliminate – a variety of existing explanations and posit our argument on democratic representation and party system collapse. However, the comparative method is limited by its design for a specified universe of cases. While our application of this method has shown that our findings apply to Greece, Portugal and Spain, the question arises whether these findings may be generalized beyond our sample. If we are right and our argument has external validity, countries that are experiencing economic crisis and extreme right party support are more likely to exhibit low or declining levels of trust in state institutions, declining perceptions of state capacity and severe problems of governability. Based on the findings obtained here, future research could examine other countries that have experienced economic crisis in greater detail, looking at the relationship between the rise of right-wing extremism and crises of democratic representation. For example, the rise of Jobbik in Hungary could provide a good platform for testing our argument. Future research could also identify limits or additional circumstances that may alter dynamics in different settings; for example, explaining the limited support for the Cypriot National Popular Front (ELAM), which is a sister party of the Golden Dawn. Finally, future research could focus on an analysis of the strategies and discourses of extreme right parties in order to nuance the ways in which these parties may themselves shape their own electoral fortunes when structural conditions are ripe.