Impact statement

Migrants face multiple stressors before, during and after migration, increasing their risk of mental health difficulties. However, accessing psychological support remains a challenge due to structural, cultural and practical barriers. Scalable, low-intensity interventions, such as the World Health Organization (WHO)’s Doing What Matters in Times of Stress (DWM) and Problem Management Plus (PM+), offer promising solutions to address these challenges, particularly when delivered through a stepped-care approach.

This study presents a process evaluation of a stepped-care mental health program for migrants in Italy, highlighting key factors that influence its implementation and effectiveness. Findings indicate that cultural perceptions of mental health, digital accessibility and the role of community leaders are critical in shaping engagement. While many participants found the interventions beneficial and accessible, some faced challenges related to digital literacy and stigma. Importantly, the flexibility of helpers, trust-building through community involvement and gradual engagement in mental health strategies emerged as key facilitators of intervention uptake and adherence.

These insights provide valuable guidance for policymakers, mental health practitioners and organizations aiming to scale up psychological support for migrants. The study underscores the importance of culturally sensitive adaptations, digital literacy support and collaboration with community leaders to maximize intervention reach and impact. By addressing these factors, stepped-care psychological interventions can be effectively integrated into migrant mental health services, ensuring that support is both accessible and sustainable for diverse populations.

Introduction

According to the latest estimates from the United Nations, there are approximately 281 million international migrants worldwide, representing 3.6% of the global population. This increase is part of a broader trend where more people are displaced, both within their own countries and across borders, due to factors like conflict, violence, political and economic instability and, increasingly, climate change and natural disasters. Italy remains a key entry point for migrants arriving in Europe, with 34.000 new arrivals recorded in 2020 and nearly 60,000 in 2021. While migration can offer new opportunities, it is also associated with significant challenges that can adversely affect mental health, particularly among forcibly displaced populations such as refugees and asylum seekers (McAuliffe and Oucho, Reference McAuliffe and Oucho2024).

Migrant populations can be exposed to various stressors throughout the migration trajectory, spanning pre-migration, migration and post-migration phases. Pre-migration challenges often include traumatic experiences such as conflict, violence, persecution and displacement. The migration journey itself can involve unsafe travel conditions, exploitation and legal uncertainties. In the post-migration phase, migrants may face challenges such as discrepancies between expectations and achievements, lack of social support, acculturation difficulties, discrimination, as well as financial or legal instability (Jurado et al., Reference Jurado, Alarcón, Martínez-Ortega, Mendieta-Marichal, Gutiérrez-Rojas and Gurpegui2017). These stressors contribute to an increased risk of common mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Patanè et al., Reference Patanè, Ghane, Karyotaki, Cuijpers, Schoonmade, Tarsitani and Sijbrandij2022). Addressing the mental health needs of migrants is, therefore, an urgent public health priority.

Psychological interventions have shown promise in reducing symptoms of depression, anxiety and somatization among migrants, with a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) highlighting their efficacy in improving these conditions (Sambucini et al., Reference Sambucini, Aceto, Begotaraj and Lai2020), while mixed-methods studies suggest that they can also enhance mental health outcomes and social functioning (Apers et al., Reference Apers, Van Praag, Nöstlinger and Agyemang2023). However, there are barriers to implementing traditional psychological interventions in resource-constrained and culturally diverse settings (Costa et al., Reference Costa, Olson, Mescouto, Setchell, Plage, Dune, Creese, Suleman, Prasad-Ildes and Ng2025). These include the need for extensive training, time-intensive delivery models, reliance on mental health specialists and face-to-face individual sessions.

To overcome these challenges, scalable psychological interventions such as Doing What Matters in Times of Stress (DWM) (World Health Organization, 2020) and Problem Management Plus (PM+) (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Bryant, Harper, Kuowei Tay, Rahman, Schafer and van Ommeren2015) have been developed by the World Health Organization. Both interventions are designed to be transdiagnostic, addressing a broad range of symptoms across mental health conditions, and task-shifting, enabling delivery by non-specialist providers to reduce costs and overcome workforce shortages, making them suitable and accessible for diverse populations. DWM is a self-help intervention based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) principles, providing practical strategies for stress management, while PM+ is a brief, structured psychological intervention designed for individuals experiencing significant distress, incorporating problem-solving and behavioral activation strategies to address psychological distress. It integrates cognitive-behavioral and problem-solving strategies to address psychological distress. Combined as part of a stepped-care program, a model that offers patients the least intensive intervention required for their mental health needs, advancing to more intensive treatments only as necessary, these interventions aim to provide tailored support based on individuals’ mental health needs, starting with DWM, and then offering PM+ to those who continue to experience persistent and significant psychological distress, while optimizing resource use (Jeitani et al., Reference Jeitani, Fahey, Gascoigne, Darnal and Lim2024).

While the efficacy of the DWM and PM+ interventions has been demonstrated in various populations, such as healthcare workers (Riello et al., Reference Riello, Purgato, Bove, Tedeschi, MacTaggart, Barbui and Rusconi2021; Mediavilla et al., Reference Mediavilla, Felez-Nobrega, McGreevy, Monistrol-Mula, Bravo-Ortiz, Bayón, Giné-Vázquez, Villaescusa, Muñoz-Sanjosé, Aguilar-Ortiz, Figueiredo, Nicaise, Park, Petri-Romão, Purgato, Witteveen, Underhill, Barbui, Bryant, Kalisch, Lorant, McDaid, Melchior, Sijbrandij, Haro and Ayuso-Mateos2023) and individuals affected by adversity (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Leku, Lakin, Carswell, Augustinavicius, Adaku, Au, Brown, Bryant, Garcia-Moreno, Musci, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2020; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Carswell, Tedeschi, Acarturk, Anttila, Au, Bajbouj, Baumgartner, Biondi, Churchill, Cuijpers, Koesters, Gastaldon, Ilkkursun, Lantta, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Papola, Popa, Roselli, Sijbrandij, Tarsitani, Turrini, Välimäki, Walker, Wancata, Zanini, White, van Ommeren and Barbui2021; Acarturk et al., Reference Acarturk, Uygun, Ilkkursun, Carswell, Tedeschi, Batu, Eskici, Kurt, Anttila, Au, Baumgartner, Churchill, Cuijpers, Becker, Koesters, Lantta, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Popa, Purgato, Sijbrandij, Turrini, Välimäki, Walker, Wancata, Zanini, White, van Ommeren and Barbui2022; Schäfer et al., Reference Schäfer, Thomas, Lindner and Lieb2023), independent participant data analysis across studies indicates that many people are still symptomatic following these interventions (Akhtar et al., Reference Akhtar, Koyiet, Rahman, Schafer, Hamdani, Cuijpers, Sijbrandij and Bryant2022). This has led to calls for stepped-care approaches that offer interventions of increasing intensity for people who do not initially respond to the initial intervention (Bryant, Reference Bryant2023).

An RCT conducted in Italy evaluated the effectiveness of guided DWM and PM+ delivered as a stepped-care program to reduce anxiety and depression symptoms among migrants, with the interventions demonstrating effectiveness in improving mental health outcomes (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Tedeschi, Turrini, Cadorin, Compri, Muriago, Ostuzzi, Pinucci, Prina, Serra, Tarsitani, Witteveen, Roversi, Melchior, McDaid, Park, Petri-Romão, Kalisch, Underhill, Bryant, Mediavilla Torres, Ayuso-Mateos, Felez Nobrega, Haro, Sijbrandij, Nosè and Barbui2025).

RCTs are widely considered the gold standard for assessing the effectiveness of interventions; however, they often provide limited insights into the underlying processes of how and why an intervention achieves its outcomes (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Audrey, Barker, Bond, Bonell, Hardeman, Moore, O’Cathain, Tinati, Wight and Baird2015). In this context, process evaluations are essential for interpreting trial results, as they delve into the complexities of implementation, exploring how interventions appeal to and are delivered, received and experienced by end users. Additionally, they illuminate the broader context in which the intervention operates, including the social, cultural and systemic factors that may influence its success or limitations (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Audrey, Barker, Bond, Bonell, Hardeman, Moore, O’Cathain, Tinati, Wight and Baird2015). Process evaluations are particularly crucial for hypothesizing potential mechanisms of impact and determining whether observed effects are directly attributable to the intervention or to external influences. Beyond their role in interpretation, these evaluations provide insights for the broader dissemination and scaling-up of interventions by examining their functionality, acceptability, perceived usefulness and replicability across different settings (Skivington et al., Reference Skivington, Matthews, Simpson, Craig, Baird, Blazeby, Boyd, Craig, French, McIntosh, Petticrew, Rycroft-Malone, White and Moore2021). This is especially important for complex interventions like the DWM and PM+ stepped-care programs, which often require careful adaptation to meet the unique needs of different populations and contexts.

Against this background, the present study consists of a process evaluation of the RCT, which analyzed the stepped-care program combining DWM and PM+ WHO interventions. The program was delivered in English or Italian to migrants resettled in Italy who exhibited elevated psychological distress. Using the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Audrey, Barker, Bond, Bonell, Hardeman, Moore, O’Cathain, Tinati, Wight and Baird2015; Skivington et al., Reference Skivington, Matthews, Simpson, Craig, Baird, Blazeby, Boyd, Craig, French, McIntosh, Petticrew, Rycroft-Malone, White and Moore2021), this evaluation explored the context, implementation and possible mechanisms of impact of interventions to provide insights that can inform the adaptation and scalability of psychological interventions for migrant populations.

Methods

This study is a process evaluation nested within an RCT conducted in two Italian cities, Verona and Rome, examining the effectiveness of DWM and PM+ interventions delivered as a stepped-care program in reducing anxiety and depression symptoms in a sample of migrants with elevated psychological distress. DWM was implemented as a guided intervention with 15-minute weekly support calls, while PM+ was delivered through individual one-hour weekly sessions via videoconference. A detailed protocol for this process evaluation was registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/exj7w/).

We adopted a mixed-methods approach guided by the MRC framework for process evaluations of complex interventions to structure data collection and analysis (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Audrey, Barker, Bond, Bonell, Hardeman, Moore, O’Cathain, Tinati, Wight and Baird2015). The methodology includes the consideration of three main components: (a) the context in which the stepped-care program was delivered; (b) the assessment of key implementation outcomes (such as feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness and fidelity); (c) the formulation of hypotheses on the possible mechanisms of impact through which the interventions may operate. Specifically, we aimed to explore key barriers, facilitators and mechanisms influencing the intervention’s delivery and efficacy within the Italian context, providing insights into the real-world feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness of stepped-care psychological interventions for migrant populations. These three components guided the development of research questions and informed our interview guides and focus group topic outlines. The thematic analysis was structured around the same domains, ensuring consistency and depth in data coding and interpretation.

Proctor’s Implementation Outcomes Framework (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011), developed for mental health interventions, guided the evaluation of implementation indicators, which were explicitly reflected in both the quantitative implementation outcome questionnaire and the qualitative coding framework. In parallel, we employed Bronfenbrenner’s Socioecological Model (Sadownik, Reference Sadownik, Sadownik and Višnjić Jevtić2023) to interpret the findings across multiple levels of influence, ranging from individual interactions to broader systemic and temporal factors. This model helped contextualize the results within the broader environmental and structural conditions that shape intervention engagement and outcomes.

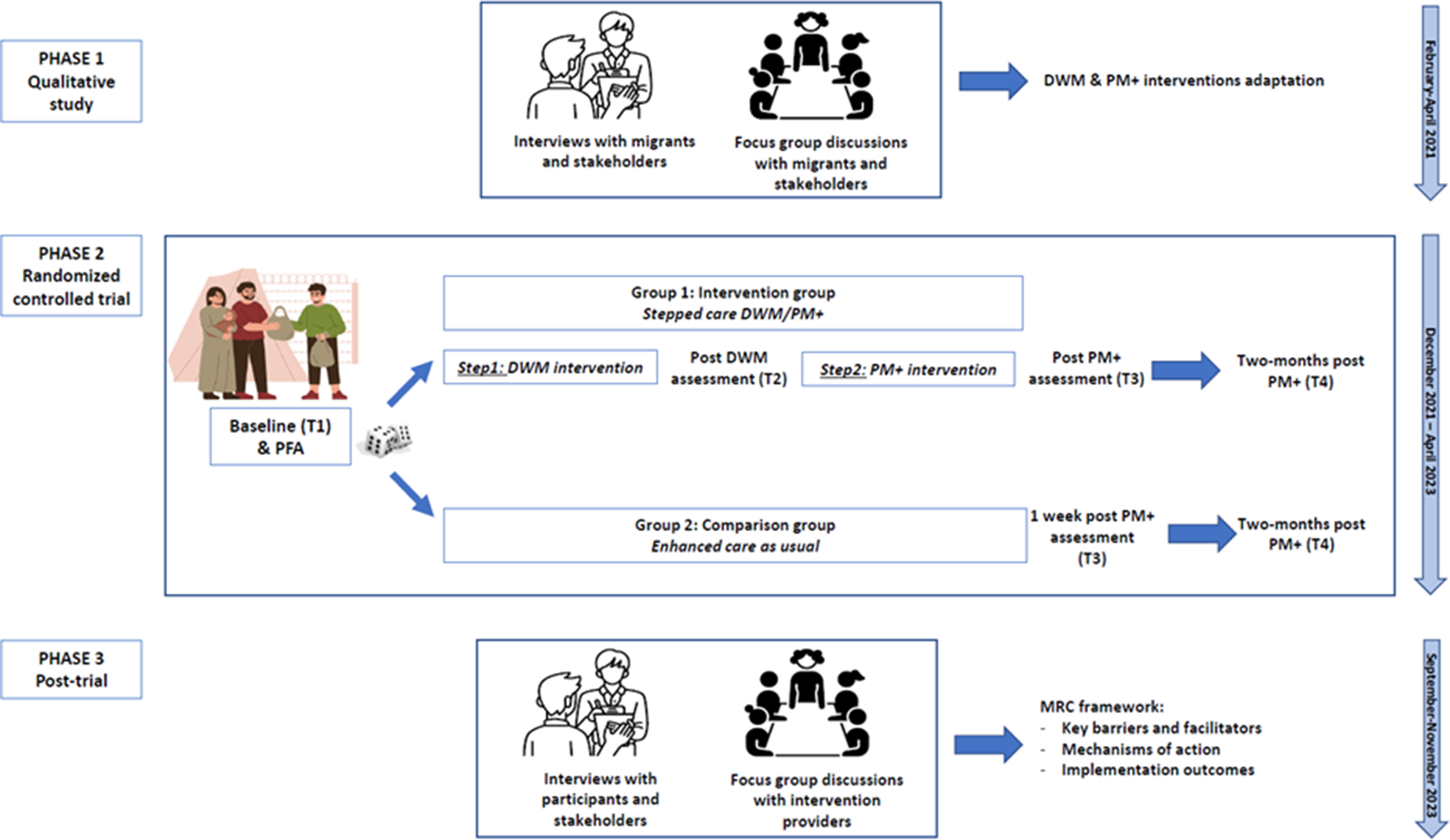

We collected qualitative and quantitative data before (February–April 2021) and during the RCT (December 2021–April 2023), and additional qualitative data at trial completion (September–November 2023) (Figure 1). For this process evaluation, we integrated the post-trial qualitative data with the qualitative and quantitative data already collected during the pre-trial and trial phases. The RCT took place in the communities of Verona and Rome, but data from its final phase were only available in the former.

Figure 1. Trial phases.

Note: DWM: Doing What Matters in Times of Stress; PM+: Problem Management Plus; T1: baseline; T2: post DWM intervention assessment; T3: post PM+ intervention assessment; T4: 2-month PM+ intervention assessment (primary outcome); PFA: Psychological First Aid; MRC: Medical Research Council. Phase 1: qualitative data collected before the randomized controlled trial (RCT). Phase 2: RCT. Phase 3: new qualitative data collected at trial completion.

To examine the context, in the first phase of the RCT, local experienced psychologists conducted individual interviews and focus group discussions (FGD) with key stakeholders (i.e., mental health professionals, non-governmental organization (NGO) staff and cultural mediators) and migrants to understand the specific needs and contextual challenges faced by migrants in Italy. These qualitative findings, presented elsewhere (Lotito et al., Reference Lotito, Turrini, Purgato, Bryant, Felez-Nobrega, Haro, Lorant, McDaid, Mediavilla, Melchior, Nicaise, Nosè, Park, McGreevy, Roos, Tortelli, Underhill, Martinez, Witteveen, Sijbrandij and Barbui2023), revealed numerous mental health and psychosocial difficulties among the migrant population. Adaptation ensured cultural and contextual relevance and tailoring of the interventions to the realities of migrants’ lived experiences (Lotito et al., Reference Lotito, Turrini, Purgato, Bryant, Felez-Nobrega, Haro, Lorant, McDaid, Mediavilla, Melchior, Nicaise, Nosè, Park, McGreevy, Roos, Tortelli, Underhill, Martinez, Witteveen, Sijbrandij and Barbui2023). After the end of the trial, two local psychologists conducted in-person individual interviews with participants who completed or discontinued the interventions, as well as with local stakeholders (i.e., NGO staff, healthcare professionals). They also conducted an FGD with the intervention providers (also referred to as “helpers”) to explore the barriers and facilitating factors influencing intervention implementation.

To assess how the programs were implemented, focusing on the resources and processes used to deliver the intervention and the quantity and quality of delivery, we relied on key implementation indicators such as acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility and fidelity (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011). For this purpose, we gathered quantitative data from the trial phase using Castor Electronic Data Capture (EDC) software (Castor, 2019). This included recruitment and participation rates, adherence to intervention protocols and quality of delivery, measured through an ad hoc reporting form, structured observation and listening to at least 10% of DWM and PM+, as well as supervision sessions. At trial completion, quantitative data were also collected, and three implementation outcome measures were administered to assess the acceptability, appropriateness and feasibility of DWM/PM+ interventions from the participants’ point of view. Specifically, the following measures were used: Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM), Intervention Appropriateness Measure (IAM) and Feasibility of Intervention Measure (FIM) (Weiner et al., Reference Weiner, Lewis, Stanick, Powell, Dorsey, Clary, Boynton and Halko2017). In addition, the analysis of implementation indicators was also performed using data from individual interviews with trial participants and stakeholders, as well as the focus group with the intervention providers. All implementation outcomes were described and analyzed following Proctor et al. guidelines (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011).

Mechanisms of impact were explored during the individual interviews with trial participants on how intervention activities and participants’ interactions with them and with the intervention providers triggered change, using constructs such as participants’ responses and adverse events.

Analysis

The qualitative and quantitative data were analyzed separately. Quantitative data were obtained through routine monitoring conducted during the RCT, as well as from structured observation checklists used by supervisors and listening sessions. Descriptive statistics such as means and standard deviations or percentages were employed to describe the results.

Qualitative data collected at trial completion through individual interviews and a focus group discussion were recorded, transcribed and coded using NVivo software. We adopted a hybrid thematic analysis approach, combining inductive methods with deductive elements based on the MRC’s framework. The analysis was conducted at a semantic level, following a realist perspective to ensure that themes emerged directly from the participants’ data (Proudfoot, Reference Proudfoot2022). Code words or phrases were applied to sections of text to reliably represent the concepts described by the participants. This process was iterative, involving multiple readings of the data to refine emerging themes. Data saturation was assessed by continuously analyzing the material until no new themes or insights emerged, ensuring a comprehensive representation of participants’ perspectives. This analysis was conducted independently by the two interviewing researchers on original data (Italian) and then translated into English. The lists of codes were subsequently shared, and ambiguities and discrepancies in coding the qualitative data were discussed and resolved in consultation between both data analysts. Then, similar codewords and phrases were regrouped together and renamed into themes, following Braun and Clarke’s guidelines for thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Results were then organized using the final coded themes, with representative quotations used for illustration, and using the MRC’s framework components (context, implementation and mechanisms of impact) as the coding frame. This methodology ensured that participants’ thoughts, words and experiences remained central to the findings and enhanced the study’s relevance.

To evaluate implementation indicators, we applied Proctor’s Implementation Outcomes Framework, ensuring that key constructs such as acceptability, feasibility and appropriateness were systematically examined. The three implementation outcome measures administered to trial participants at trial completion ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater acceptability, appropriateness or feasibility (Weiner et al., Reference Weiner, Lewis, Stanick, Powell, Dorsey, Clary, Boynton and Halko2017).

To interpret the findings across multiple levels of influence, we employed Bronfenbrenner’s Socioecological Model, allowing for an in-depth understanding of how individual, interpersonal, community and systemic factors shaped the intervention’s implementation and impact (Sadownik, Reference Sadownik, Sadownik and Višnjić Jevtić2023). The Socioecological Model assumes that an individual’s well-being and behavior are influenced by interactions across different levels. The microsystem, which is closest to the individual, includes influences, interactions and relationships within the immediate surroundings. The second level, the mesosystem, examines interactions between different areas such as work, school, church and neighborhood. The exosystem does not directly affect the individual but has an indirect impact through factors such as community contexts and social networks. The macrosystem includes broader social, religious and cultural values and influences. Finally, the chronosystem considers the internal and external elements of time, reflecting how changes over time affect an individual. The interviews and the analysis were conducted by two female clinical psychologists, both with extensive experience working with culturally diverse populations, including migrants (i.e., asylum seekers, refugees and economic migrants). While neither researcher had a migration background, they were aware of the influence their professional and cultural positions might have on the research process. To minimize personal bias, the interviewers adopted a reflexive approach throughout each phase of the project. This included regular supervision sessions where the researchers reflected on how their experiences, identities and subjectivities shaped and informed their interactions with participants. Activities such as project meetings, group reflection and contemporaneous feedback processes were employed to refine thinking, analysis and writing. To further mitigate bias, the semi-structured interview guides were used to encourage open-ended responses, and non-directive questioning was emphasized. Discrepancies in interpretation were resolved collaboratively, and findings were triangulated with input from helpers and stakeholders to ensure a balanced and comprehensive understanding.

Ethics

Participants completed an information sheet and signed an informed consent form. The Comitato Etico per la Sperimentazione Clinica delle Province di Verona e Rovigo reviewed and approved the study, Approval ID 46725 of 10/08/2021.

Results

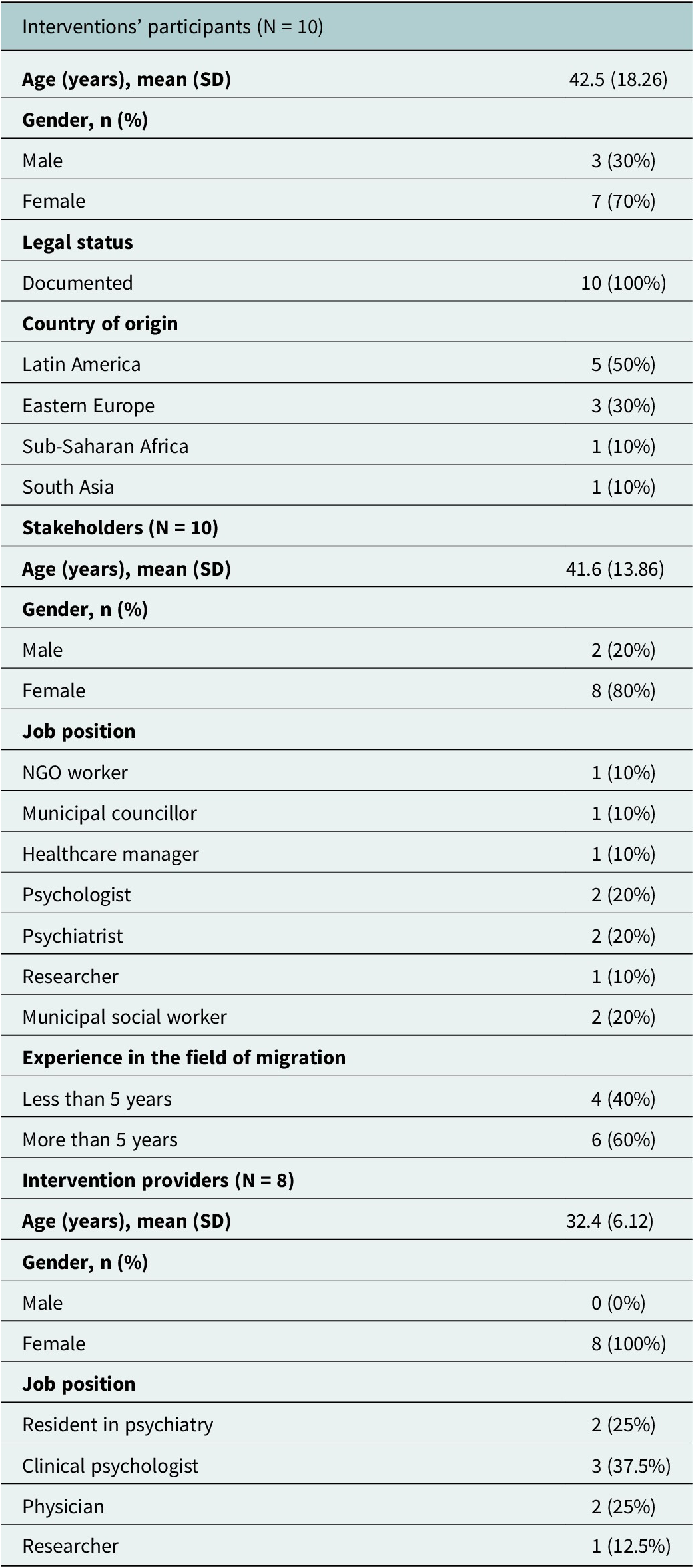

As part of the post-trial phase, individual interviews were conducted with participants in the intervention group who voluntarily decided to participate and included those who (a) completed the DWM intervention only (n = 4), (b) completed the whole DWM/PM+ intervention (n = 4) and (c) did not complete the DWM or PM+ sessions (n = 2). Among these, seven were women and three were men, with an average age of 42.5. They came from diverse backgrounds, including Latin America (n = 5), Eastern Europe (n = 3), Sub-Saharan Africa (n = 1) and South Asia (n = 1).

Additionally, ten stakeholders were interviewed, including three psychiatrists, two psychologists, one researcher, an NGO worker, a municipal councillor, a healthcare manager and a municipal social worker. Eight were women, and their average age was 41.6.

Furthermore, a focus group discussion was conducted with eight helpers, all of whom were women with an average age of 32.4. The helpers included two residents in psychiatry, three clinical psychologists, two physicians and a researcher, all closely supervised by senior mental health practitioners (Table 1).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics

Note: SD = standard deviation; NGO = non-governmental organization.

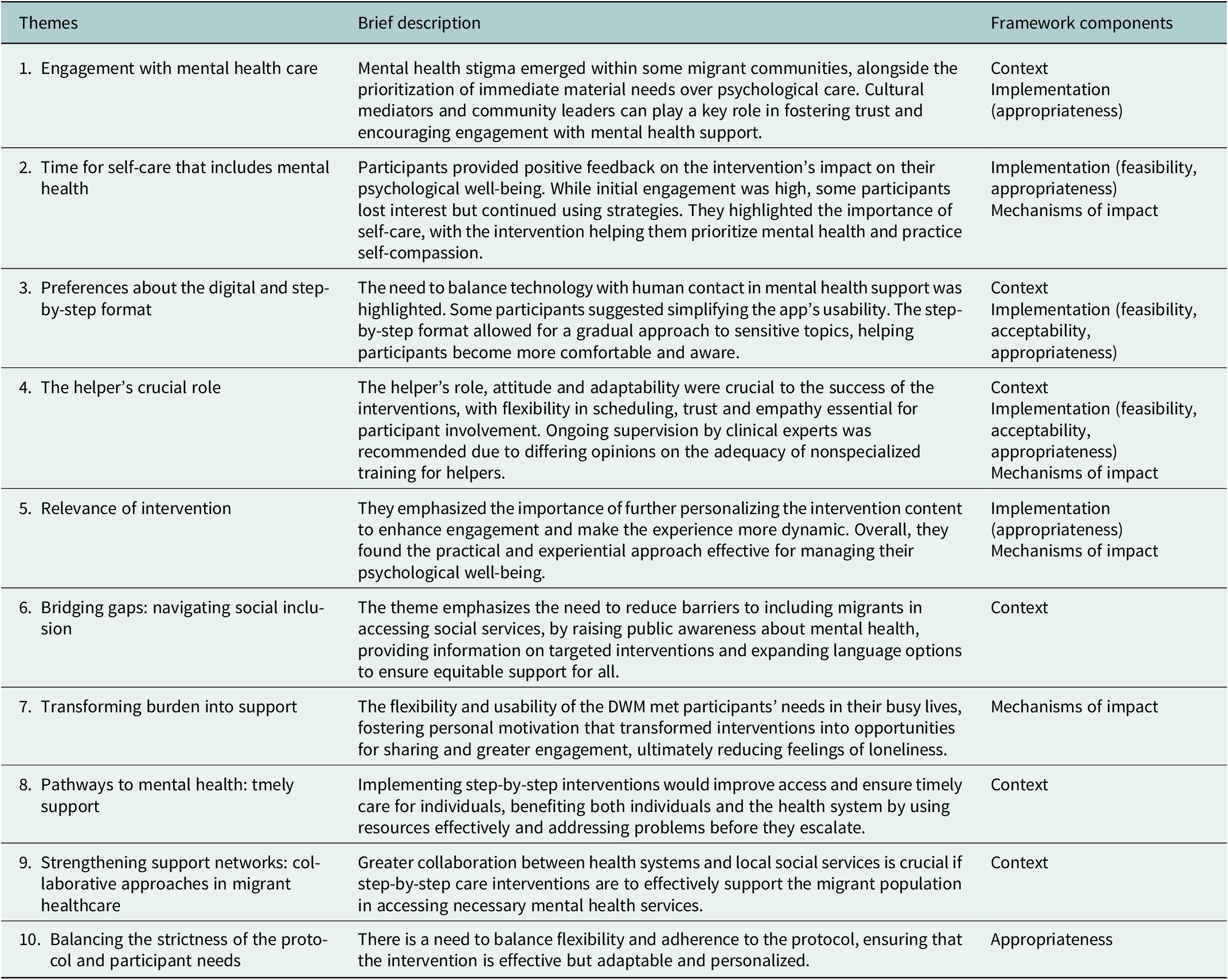

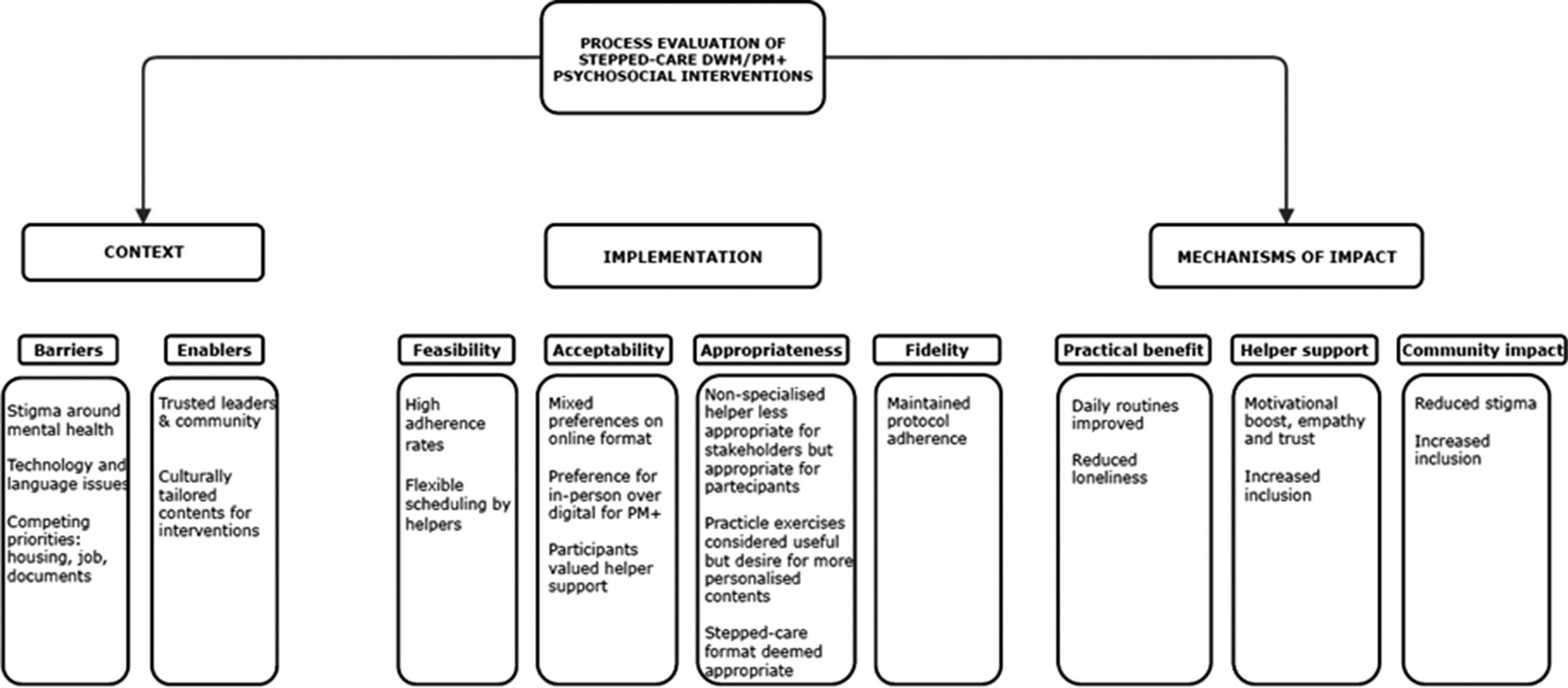

The themes in Table 2 emerged from codes from the thematic analysis of interviews with participants, stakeholders and focus groups with intervention providers conducted during the post-trial phase. These themes have been classified according to the three components of the MRC framework: context, implementation and mechanisms of impact (Figure 2).

Table 2. Key themes identified from one-to-one interviews with participants and stakeholders and focus groups with intervention providers

Figure 2. Integrative model of context, implementation and mechanisms of impact.

Context

Participants identified barriers and enabling factors for the implementation of DWM and PM+. A primary barrier identified by both stakeholders and interviewed participants was the mental health stigma present within some of the migrant communities involved in the study, which influences attitudes toward mental health and help-seeking (Theme 1). [“Culturally, mental health is a taboo (in Albania); everything is discussed except mental health. As soon as this topic is raised, you are considered crazy or perceived as something wrong.” P1, female].

Another contextual barrier, often mentioned by stakeholders, was the migrant population’s prioritization of practical concerns such as employment, securing documents and housing. As a result, mental health and psychological distress were often perceived as lower priorities compared to these immediate material needs, making psychological interventions more likely to be viewed as an additional burden rather than an opportunity. (Theme 1)

[A person who arrives in our country, or specifically in our city, wants to secure a place to stay, documents, and a job. These young people prioritise work to send money home, and mental health is not a priority. They are very practical and have concrete needs like housing, work, and money for food. S1, female].

Another issue reported mainly by stakeholders, but also by some of the participants, is the mistrust that migrants have toward psychological interventions and providers. This resulted partly from a lack of familiarity with such interventions and partly from fear. They reported that this could happen especially among those dealing with complicated bureaucratic processes and think that opening up could lead to negative consequences (Theme 1). This leads to a lack of trust and reluctance to rely on such initiatives. According to stakeholders, this obstacle could be overcome with the help of a cultural mediator or a community leader (Theme 1). [“Migrants naturally have to defend themselves because, from departure to arrival, the world can be hostile: the smugglers, those who receive them, the work environment. It’s clear that people who migrate often develop a greater sense of mistrust compared to Italian citizens.” S2, male]. The presence of trusted people and community leaders who promote initiatives aimed at psychological well-being would allow for greater awareness of mental health issues. This would reduce the stigma surrounding mental health and the perception of marginalization and exclusion among the migrant population regarding access to these types of services (Theme 6). This would increase a sense of inclusion and community. [“In my opinion, mediators or community leaders are essential. In my personal experience, without them it would be a huge task that would not even be worth undertaking, because it becomes extremely difficult. So, basically, it is necessary to have them.” S3, male].

Furthermore, this would allow a larger number of people to be reached, with resulting benefits both at the individual and societal levels (Theme 8). [“Reaching more people by making the approach accessible and specific could attract those who wouldn’t typically seek psychiatric help, thereby increasing participation and outreach.” S4, female].

On the other hand, the issues primarily raised by participants concerned technology, remote delivery and the need to find a private space within their homes or other accommodations. Another issue is the language barrier, which may have decreased motivation. Technology was sometimes seen as a barrier for different reasons: partly because of the older generation’s difficulty in using it, and partly due to a preference for in-person meetings and face-to-face relationships (Theme 3). [“I wasn’t so enthusiastic about online sessions, especially when discussing personal matters, because sometimes you might be speaking and the connection drops…” P2, female].

On the other hand, some participants considered technology as a facilitator to intervention participation (Theme 3) and also believed it provided greater flexibility, according to some of the interviewed stakeholders (Theme 4). [“The distance in that case helped me because at the time I was in Romania for a few weeks… If it hadn’t been like that, I might have missed 3 weeks of meetings.” P3, male].

Another aspect that, according to participants, may have facilitated good compliance with the proposed intervention seems to have been the first in-person explanatory meeting (Theme 3) and the relational approach of the helpers in following up and motivating participants to continue practicing the skills learned for their own well-being (Theme 4).

[The relational aspect is crucial. Without the initial calls, the experience would have been tedious, and I might have lost interest and stopped using it. The calls, including the video ones, provided extra motivation. Knowing that someone is reaching out and paying attention encourages you to keep going and use the app. P1, female].

Similarly, the focus group with the intervention providers highlighted aspects similar to those mentioned above. Some helpers noted that the cultural issue, characterized by a lack of familiarity with mental health topics, the concept of mental health itself and the priority given to other life aspects, sometimes made the intervention implementation more challenging. This made helpers feel that participants sometimes perceived the proposed program as a burden rather than an opportunity for self-care (Theme 1).

[In my view, the challenge was shifting from seeing it as a commitment to viewing it as an opportunity. I also reflected on what E. (a helper) said about taking an hour each week for oneself. It depends on our perspective—if I view it as a commitment rather than as something for myself, as a chance. I think the challenge lies in changing that perspective a bit. H1, female].

Other aspects mentioned by intervention providers include the difficulty some participants had in understanding the explained concepts, mainly because they are not part of their own cultural background (Theme 6).

Other aspects mentioned by intervention providers include the need to adapt to participants’ schedules and preferences for calls (Theme 4). [“For example, some participants needed to speak outside regular hours and often requested unconventional times. I had many calls with one participant on Sundays, and handling 15-minute calls was easier. However, longer calls required a more protected and organized space, especially when I had two in the same week.” H2, female].

Finally, we asked stakeholders how this type of intervention could successfully be implemented in Italy. They suggested that for effective scalability, it would be necessary to move away from culturally centralized conceptualizations of mental health, shaped by the norms, values and practices of the dominant culture and adopt a more inclusive approach that takes into account the diverse cultural beliefs and experiences of migrant populations. They also emphasized the need for a deeper understanding of the participant’s cultural background and migration process, which would improve overall comprehension of the individual (Theme 1).

[We often think within our own culture without stepping outside of it, which limits our understanding of what others may have experienced and where they come from. Ultimately, it is always a communication issue and a gap in cultural knowledge of the person in front of you. I notice that I tend to bring everything back to this. S3, male].

Stakeholders agreed on the need for preventive interventions, such as DWM and PM+ in our society, in response to increasing psychological distress (Theme 8). To scale up effectively, stakeholders proposed strengthening preventive pathways for psychological distress that involve local or regional community efforts, fostering synergy and cooperation. They also suggested ensuring direct links with specialist services when needed. Finally, they proposed the possibility of providing participants with booster sessions to maintain the efficacy of the intervention over time (Theme 9). [“I think it is useful to have a step-by-step structure because the first step can promote broader prevention, aiming to reduce costs for the national health system by avoiding frequent hospitalisations or visits due to worsening conditions.” S5, female].

Implementation

We analyzed the intervention’s feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness and fidelity, according to Proctor and colleagues’ guidelines (2011) (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Silmere, Raghavan, Hovmand, Aarons, Bunger, Griffey and Hensley2011). The three implementation measures (AIM, IAM and FIM) filled out by trial participants after the interview revealed that 90% of participants found the interventions acceptable, appropriate and feasible.

Feasibility Over a 17-month recruitment period, 238 potential participants were reached via key stakeholders, community organizations offering legal, social or psychosocial support, and through social media and word of mouth. Out of these, 217 were randomized. Eight individuals affiliated with the University of Verona were invited to participate as intervention providers (helpers) for the study. They were selected based on their interest in psychosocial support and their willingness to undergo training in delivering the intervention. All of them chose to participate in the training, which was conducted through in-person sessions between September and October 2021: eight full days for PM+ and four full days for DWM. Clinical psychologists and psychiatrists provided intervention supervision, addressing their questions and offering debriefing after sessions. Additional training and consultation were available as needed. The total supervision time required for all sessions of DWM and PM+ was 3 hours per helper on average (approximately 12 hours in total).

Opinions were mixed regarding the role of the helpers and their nonspecialized mental health training. While there was recognition of the need to optimize available resources, concerns were raised that nonspecialized helpers may not fully grasp critical clinical aspects. All stakeholders pointed out the necessity, for scalability purposes, of implementing tools to guarantee the quality of the intervention, such as role-playing and ongoing supervision from specialists (Theme 4).

[I think we should use tools like EQUIP for quality, which are already in place. Providing feedback, role-playing, and ongoing supervision are crucial, emphasising basic helping skills because that’s ultimately their main role—knowing how to interact, empathise, and what not to do… I believe it would also be important to dedicate more time and space to assessment and supervision. S5, female].

During the focus group, intervention providers highlighted the overall feasibility of the intervention for participants. Both intervention providers and participants emphasized that the flexibility of the helpers was crucial in ensuring the continuity of the intervention and adherence to protocols. This flexibility involved accommodating participants’ schedules and adapting to their needs (Theme 4). [“Every time we organised ourselves. Everything was perfect. We easily found a common moment. We agreed, you can call me when I’m more available. I’m calmer in the evening.” P3, male].

In terms of long-term feasibility, participants expressed a decline in active engagement with the app over time. While some stopped using the application directly, many continued to apply strategies like breathing exercises and listening to audio sessions autonomously (Theme 2). [“I do not listen to the audio anymore because I’ve already learned the strategies, but I used to listen to them, especially when I forgot a step.” P4, female].

However, the decline in consistent use of the app highlighted potential challenges in maintaining long-term engagement. [“I think the issue might be maintaining the use of the tool over time.” P5, male].

Finally, a suggestion from the intervention providers was to convert the web page into a full-fledged app to improve accessibility and usability (Theme 3).

Acceptability

The attrition rate for the complete stepped-care program was low: 13 out of 108 completed less than 3 DWM sessions (12%), and 12 completed less than 4 PM+ sessions (20%). Overall, DWM participants preferred synchronous support (i.e., 15-minute weekly phone calls) over asynchronous contact (i.e., weekly messages through the DWM website), with only four participants opting for the latter after the initial DWM welcome call.

Regarding the acceptability of the proposed intervention, all participants provided positive feedback, including the two who discontinued the intervention sessions. According to the interviewed participants, the role of the helper was very important and seen as an essential and nonintrusive resource (Theme 4). [“In my opinion, the phone calls were very positive because I felt wanted and listened to, as she showed interest in what I was doing. (…) Through the phone calls, I felt more heard and more important. My relationship with her made a difference.” P4, female].

The helpers’ calls were seen as necessary, both by participants and intervention providers, crucial for motivational support, technological assistance, as a listening space and also for a better understanding of some concepts and strategies of the proposed intervention (Theme 4). [“If there hadn’t been the helper’s role (…) if they had to do it alone, it would have been a bit complicated.” H3, female].

Almost all participants also appreciated and accepted the online format and the stepped-care delivery. Overall, the online format received positive feedback, especially for DWM. By contrast, for PM+, several interviewees expressed a preference for in-person sessions, given the potentially more sensitive topics addressed. They acknowledged the convenience of being able to attend sessions from home, but emphasized the preference for face-to-face interaction (Theme 3). [“If it had been in person, it would have been better… I always prefer face-to-face contact; I feel like express myself better in person; For these things, it’s better to do it in person.” P5, male].

Appropriateness

Positive feedback emerged from the participant interviews regarding the proposed intervention despite the low familiarity with mental health and its prevention (Theme 1).

The participants liked the guided audio exercises, the practical exercises and the action plan the most, which was evaluated as very useful. This program structure greatly encouraged the practice of the strategies, leading participants to use them even long after the end of the program (Theme 2). [“I remember there were goals to write down, and I would print them out and put them in my bag, because we often get caught up in all we do. I still use it today to help me sleep when I have difficulties.” P5, male].

Regarding the proposed content specifically aimed at the migrant population, the overall feedback was positive from participants, stakeholders and intervention providers. [“Then I called all my friends, my sister-in-law. I told them, ‘Go there, go get the treatment because we are foreigners, we have that depression inside, the thought of going home, we are sick inside because we are not in our own home… we always have our home on our mind. At least it’s a way to relax.’” P6, female].

However, during individual interviews, participants expressed some criticisms. They noted that the content was not fully personalized, sometimes redundant and not very engaging (Theme 5). [“It seemed like each module was always a bit the same. I felt like I was doing the same things multiple times. The questions within the same module were repetitive.” P3, male].

Intervention providers also agreed with some of these observations, such as the need for more individualized interventions. For instance, they reported that a female participant had a negative experience with the audio exercises, as she felt uncomfortable with the male voice used in the recordings. This issue may have been influenced by cultural factors (Theme 5).

Some participants found the online delivery less appropriate due to reduced personal interaction with the helper. Indeed, some participants suggested increasing the number of weekly calls or extending their duration to meet the need for more relational contact during DWM. They emphasized the importance of calls with the helper to feel supported, as the strategies provided alone were insufficient for everyone, highlighting the strong need for a supportive relationship (Theme 3). [“The call was good: I felt important, as if you were saying ‘I’m here, I see you.’ It made a difference for me.” P4, female].

The stepped-care model was deemed appropriate by participants, stakeholders and intervention providers. This positive evaluation stemmed from its gradual building of a relationship with the helper, progressively increasing familiarity with such interventions and topics. (Theme 3).

[It’s a good combination—gradual and completing the journey. The second part, through a video call, in my opinion, gave a more comprehensive meaning to the process. It’s very important because if you go through it without preparation, it’s very difficult. It’s not easy to do those exercises, understand them, and reflect on those things. P7, female].

On the key role of the helper and their nonspecialized training in mental health, opinions varied among participants, stakeholders and intervention providers. Participants’ evaluations indicate they found the helpers who supported them to be appropriate, without perceiving their lack of specialized training. They emphasized the helpers’ social and supportive skills, which they considered very adequate (Theme 4). [“She was well-prepared and perfect for the role—competent. I never felt uncomfortable… the tone of voice, how she spoke to me, how she approached me… all non-judgmental.” P8, male].

Stakeholders shared various opinions. They appreciated the nonspecialized helper for providing a gradual introduction to mental health, countering an overly medicalized system. However, there is a concern about their ability to identify situations needing more structured support. Overall, they considered the helper role more suitable for DWM than for PM+, suggesting the possibility of having a former participant trained as a helper (Theme 4).

During the focus group with intervention providers, some of them expressed a feeling of discomfort and frustration related to the fear of not having the right skills to help participants and the difficulty in sticking to the intervention protocol (e.g., timing of sessions) or the temptation to give advice (Themes 4 e 10). [“My sense of discomfort wasn’t related to DWM or PM+, but rather to not having the right tools to respond adequately to certain problems.” H3, female].

Fidelity

Fidelity was checked by the intervention supervisor, a clinical psychologist who observed at least 10% of DWM sessions and listened to at least 10% of recorded PM+ sessions. The fidelity of over 10% of intervention sessions was nearly perfect. Only a few DWM calls were longer than 30 minutes. Minor deviations from the PM+ protocol were identified, primarily due to cultural adaptations and content that only partially applied to participants’ problems and/or experiences.

Mechanisms of impact

The mechanisms of impact primarily emerged from individual interviews conducted with trial participants. One identified mechanism of impact was related to the specificity of DWM activities and the weekly action plan. This means that participants perceived the benefits of the proposed practices, finding them useful in their daily routine. As a result, the program allowed participants to focus more on their mental health by helping them recognize and prioritize their emotional well-being. It encouraged them to listen to their own needs, reflect on their feelings and dedicate intentional time for self-care. This approach enabled them to connect with themselves on a deeper level, fostering a sense of emotional awareness and self-compassion (Theme 2), facilitated by the exercises, particularly those emphasizing mindfulness and living in the present moment (Theme 5). [“Carving out a little space for ourselves, as individuals, goes beyond basic needs; it’s also about how I feel and taking better care of myself. For example, there are times when I’m a bit stressed, working a lot, and the app’s questions help open up my mind." P3, male].

The intervention’s second mechanism of impact was the relationship with the helper, who provided a motivational boost to continue. This relationship proved crucial not only as an encouragement to put into practice the strategies learnt but also for its capacity to welcome, listen and support the participant (Theme 4).

[I never felt uncomfortable… the tone of her voice, the way she spoke to me, her attitude… all non-judgmental. It was clear she understood me when I talked about my experiences, and she was very patient, so I trusted and relied on her easily. I found someone who truly listened to me and cared about my well-being. P4, female].

Moreover, the constancy of the weekly appointments strengthened the motivation to continue the program, even when the tiredness of daily life could hamper continuity. Telephone calls and exercises proved useful for some participants in dealing with moments of loneliness (Theme 7).

[I saw the consistency of the appointments as a good thing. I couldn’t wait to start the programme, even though it lasted a long time. I was sorry when it ended. During that time, my husband was working and away from home all day, so I was home alone. The programme helped me manage my time. P6, female].

We did not find any serious adverse events during the RCT.

The socioecological perspective

The migration experience emerged as a prolonged and multifaceted process with significant psychological implications for migrants, aligning with the concept of the chronosystem in Bronfenbrenner’s Socioecological Model.

At the microsystem level, the psychological interventions we implemented positively impacted psychological well-being, demonstrating their benefits across diverse cultural backgrounds. Some participants chose not to share their participation in the project with their families due to concerns about stigma, while others, from different cultural contexts, actively involved their family members.

Within the mesosystem, the community played a crucial role in the success of the interventions. The increased recognition of the importance of psychological support within migrant communities helped boost acceptance and participation, often spread through word of mouth and supported by community leaders. From the interviews and direct experience, it became clear that greater awareness and the positive role of community leaders were essential in overcoming scepticism and promoting mental health.

Implementing psychological interventions falls within the exosystem, indirectly affecting migrants through institutional frameworks. These interventions have been shown to alleviate some of the pressures on overburdened healthcare systems, particularly by emphasizing the prevention of mental health conditions. The stakeholders we interviewed highlighted that providing migrants access to preventive care could significantly reduce the need for more intensive interventions.

At the macrosystem level, psychological interventions such as DWM and PM+ can challenge the cultural stigma surrounding mental health, promoting it as an essential component of overall well-being. Among those we interviewed, younger individuals expressed a stronger need to prioritize their mental health, making them more likely to seek out such support.

Discussion

We conducted a process evaluation of the DWM and PM+ interventions, delivered as part of a stepped-care program to address psychological distress among migrants in Italy. Our findings complement those focused on the outcome evaluation, showing that the stepped-care approach was perceived as beneficial in alleviating psychological distress and symptoms while also being appropriate and well-received by participants. The interventions complied with the WHO manuals, achieving high adherence rates and positive feedback from participants and stakeholders. This evaluation, structured around the context, implementation and mechanisms of action, provides critical insights into the scalability and impact of DWM and PM+ for migrants, informing future implementation efforts in different settings.

The analysis showed that cultural attitudes toward mental health and practical priorities, like employment and housing, shaped migrants’ engagement with interventions. Mental health topics were often perceived as taboo in some migrant communities, creating difficulties in the engagement with the interventions, but community leaders and mediators helped to build trust, raise awareness and encourage participation. Most participants and stakeholders found the interventions feasible and acceptable, noting high adherence and positive feedback on their flexibility and relatability. Helpers were praised for their empathy, adaptability and motivational support, which fostered engagement. However, reliance on digital tools yielded mixed results, offering accessibility for some but challenging for those with low technological literacy or limited private spaces. The stepped-care model was well-received for its pacing, although some people suggested it could benefit from more personalization. Weekly action plans and mindfulness exercises were perceived to effectively promote self-care and reduce stress, while the supportive, nonjudgmental relationships with helpers were seen as key to sustaining motivation. These findings underscore the importance of structured, relational support in driving behavioral change and improving mental health outcomes.

The findings from our process evaluation significantly expand on the results from international research demonstrating the effectiveness of WHO’s scalable interventions in improving mental health outcomes among populations facing adversity, including migrants and other vulnerable groups (Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Carswell, Tedeschi, Acarturk, Anttila, Au, Bajbouj, Baumgartner, Biondi, Churchill, Cuijpers, Koesters, Gastaldon, Ilkkursun, Lantta, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Papola, Popa, Roselli, Sijbrandij, Tarsitani, Turrini, Välimäki, Walker, Wancata, Zanini, White, van Ommeren and Barbui2021; Acarturk et al., Reference Acarturk, Uygun, Ilkkursun, Carswell, Tedeschi, Batu, Eskici, Kurt, Anttila, Au, Baumgartner, Churchill, Cuijpers, Becker, Koesters, Lantta, Nosè, Ostuzzi, Popa, Purgato, Sijbrandij, Turrini, Välimäki, Walker, Wancata, Zanini, White, van Ommeren and Barbui2022; de Graaff et al., Reference de Graaff, Cuijpers, Twisk, Kieft, Hunaidy, Elsawy, Gorgis, Bouman, Lommen, Acarturk, Bryant, Burchert, Dawson, Fuhr, Hansen, Jordans, Knaevelsrud, McDaid, Morina, Moergeli, Park, Roberts, Ventevogel, Wiedemann, Woodward and Sijbrandij2023). These studies consistently highlight the potential of these interventions to reduce psychological distress and improve well-being across diverse cultural contexts. Even though testing effectiveness is critically important, this qualitative study further extends evidence toward implementation and cultural adaptation. It highlights the perceived value of a stepped-care approach tailored explicitly to the needs of migrants, a population often underserved due to various cultural, systemic and structural barriers, such as mental health stigma, limited access to care and language or communication difficulties (Nosè et al., Reference Nosè, Turrini and Barbui2015). Our findings demonstrate that scalable, low-intensity interventions are seen by participants to address these challenges and significantly improve the mental health of migrant populations.

A particularly notable aspect of our findings is the positive role of community leaders in enhancing intervention uptake, which is consistent with the findings of studies on migrants’ mental health. These studies underscore the significance of engaging culturally embedded helpers in facilitating access to mental health services. Apers et al. (Apers et al., Reference Apers, Van Praag, Nöstlinger and Agyemang2023) highlight the importance of community figures in bridging the gap between service providers and migrant communities, mainly by reducing stigma and discrimination, building trust and fostering engagement.

Our study also reflects broader challenges associated with the digital delivery of mental health interventions. While remote delivery offered advantages such as accessibility and convenience, it also presented barriers for some participants, particularly those with limited technological literacy or inadequate private spaces for participation. These challenges mirror broader concerns highlighted in the literature regarding the accessibility of eHealth interventions. As noted in several studies, varying levels of digital literacy, infrastructure and privacy concerns can significantly impact the effectiveness and uptake of online interventions (Mabil-Atem et al., Reference Mabil-Atem, Gumuskaya and Wilson2024). Despite these barriers, digital tools have demonstrated significant potential in expanding mental health care access, particularly among underserved populations. For instance, digital platforms have been shown to improve mental health literacy, reduce stigma and facilitate engagement, as seen in interventions targeting immigrant populations (Marchi et al., Reference Marchi, Laquatra, Yaaqovy, Pingani, Ferrari and Galeazzi2024). While challenges persist, the potential of digital tools to reach and support hard-to-reach groups remains substantial, emphasizing the need for continued research and adaptation of these technologies to overcome existing barriers.

Finally, the emphasis on preventive care in this study resonates with global mental health priorities, particularly the goals of task-shifting and resource optimization. Task-shifting, which involves delegating mental health care to nonspecialist providers such as trained community leaders or peer support workers, has become a key strategy in expanding mental health services in low-resource settings (Patel et al., Reference Patel, Saxena, Lund, Thornicroft, Baingana, Bolton, Chisholm, Collins, Cooper, Eaton, Herrman, Herzallah, Huang, Jordans, Kleinman, Medina-Mora, Morgan, Niaz, Omigbodun, Prince, Rahman, Saraceno, Sarkar, De Silva, Singh, Stein, Sunkel and UnÜtzer2018). Our study’s focus on prevention and early intervention aligns with these priorities, demonstrating the potential for scalable, low-intensity interventions to address mental health issues before they become more severe, thereby reducing the long-term burden on mental health systems. This approach is critical in the context of migrants, who may face additional barriers to accessing traditional mental health care services due to factors such as language and stigma. The transdiagnostic nature of the interventions proves valuable in addressing the diverse mental health needs of migrants, who often face a range of stressors, from trauma and displacement to socioeconomic challenges. By offering a flexible and comprehensive approach to mental health care, these interventions can more effectively meet the varying needs of migrant populations. Additionally, the task-shifting aspect enables nonspecialist providers, such as community helpers or lay counselors, to deliver psychological support, enhancing engagement and ensuring that interventions are both relevant and effective within migrant communities.

While the study demonstrated that migrant populations and stakeholders perceived DWM and PM+ as acceptable and feasible strategies for improving psychological health, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the evaluation relied on a relatively small sample of participants, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to larger or more diverse migrant or helper populations. Additionally, qualitative data collected at trial completion were exclusively from participants in Verona, while trial participants were recruited from both Verona and Rome, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings across sites. Second, the process evaluation focused mainly on qualitative data, which, while rich in detail, may be subject to biases. In this sense, we do not draw causal conclusions regarding these factors but note that the qualitative insights provide important indications on how implementation may be improved to reflect cultural and contextual differences. Third, recruitment for the trial also presented several challenges such as language barriers, gender imbalance and difficulties in reaching more marginalized subgroups, potentially introducing biases in the composition of the study sample. Additionally, the reliance on digital tools also posed challenges in terms of accessibility, with some participants facing difficulties related to technological literacy, internet connectivity and privacy concerns. These barriers may have influenced the overall engagement. Finally, while a potential personal bias related to the professional and cultural positions of the researchers could have influenced the interpretation of participants’ contributions, a reflexive approach was adopted at each stage of the project to mitigate this risk.

The findings of this study contribute to a growing international evidence base supporting the scalability of low-intensity stepped-care interventions like DWM and PM+ in vulnerable populations. They underscore the importance of adapting these interventions to address the unique cultural and logistical challenges faced by different vulnerable populations (World Health Organization, 2024). Key factors such as community involvement and digital accessibility are critical for successful implementation. In conclusion, these findings provide valuable insights into the scalable and culturally sensitive delivery of mental health interventions for migrants, highlighting both challenges and opportunities that should be considered in future research and program design.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10024.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2025.10024.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Author contribution

BC, GT and MP contributed to the study’s conceptualization, methodology, data analysis and interpretation. RB, PC, JMH, RK, VL, DM, KMG, RM, MN, ALP, PPR, AR, MS, AT, ABW and CB contributed to data interpretation and provided critical intellectual input. BC and GT drafted the manuscript, with substantial revisions from all authors. CB supervised the study, providing overall guidance and oversight. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for its accuracy and integrity.

Financial support

This work was supported by the European Commission, Horizon 2020 (grant no.101016127 - RESPOND).

Competing interests

None.

Ethical standard

The Comitato Etico per la Sperimentazione Clinica delle Province di Verona e Rovigo reviewed and approved the study, Approval ID 46725 of 10/08/2021.

Comments

Verona, 17 March 2025

Dear Editor,

I wish to submit the attached manuscript titled: “Context, implementation, and mechanisms of impact of a stepped-care WHO psychological intervention for migrants with psychological distress”, to be considered for publication in Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health. This study presents a comprehensive process evaluation of a stepped-care psychological intervention combining Doing What Matters in Times of Stress (DWM) and Problem Management Plus (PM+), developed by the World Health Organization (WHO), for migrants experiencing psychological distress in Italy.

Our findings highlight the feasibility, acceptability, and appropriateness of the stepped-care approach, while also providing valuable insights into the mechanisms of impact and contextual factors influencing the intervention’s success. The findings offer important insights into the scalability and adaptation of these interventions, underscoring the importance of cultural sensitivity, digital accessibility, and community engagement to enhance mental health support for migrant populations.

We believe this manuscript aligns well with the scope of Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, as it contributes to the growing body of evidence on the implementation and scalability of psychological interventions in diverse settings. The study’s mixed-methods approach, guided by the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework, offers a nuanced understanding of how psychological interventions can be adapted to meet the unique needs of migrant populations, with implications for global mental health policy and practice.

This manuscript is original, has not been published elsewhere, and is not under consideration by any other journal. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with its submission to BMC Health Services Research. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

I look forward to receiving your response.

Giulia Turrini

WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Training in Mental Health and Service Evaluation, Department of Neuroscience, Biomedicine and Movement Sciences, Section of Psychiatry, University of Verona, Italy.

Piazzale Scuro 10, 37134 Verona, Italy.

Tel +39-045-8124884

Fax +39-045-8027498

E-mail: giulia.turrini@univr.it