Background

The number of people forcibly displaced by conflict, violence and persecution reached a record high in 2020, estimated at 82.4 million (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2021). The mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of refugees, displaced persons and those affected by conflict or natural disaster is negatively impacted. It is estimated that more than one in five people in post-conflict settings have depression, anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, and that almost one in 10 people have a moderate or severe mental disorder (Charlson et al., Reference Charlson, van Ommeren, Flaxman, Cornett, Whiteford and Saxena2019). Although the prevalence of mental disorders and psychological distress is high and has known burdens, the expenditure is low (World Health Organization, 2017), and access to quality care in conflict settings is grossly inadequate. In 2005, the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) formed a task force that developed the Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings (IASC, 2007) which was a catalyst for addressing the wellbeing of communities affected by humanitarian crises.

MHPSS is increasingly seen as a critical, cross-sectoral component to effective and responsible humanitarian programming (Meyer and Morand, Reference Meyer and Morand2015) and continues to gain recognition as a core component of any response. However, MHPSS research has not always reflected what is happening in practice in humanitarian settings. Historically, MHPSS research has largely concentrated on identifying the rates of PTSD and depression (Moore et al., Reference Moore, Van Loenhout, De Almeida, Smith and Guha-Sapir2020). Non-specific forms of psychological distress and psychosocial problems have been less well-researched, despite being the target of most MHPSS programmes in emergencies. A number of systematic reviews have been conducted in recent years on MHPSS intervention research; these have tended to limit their scope to interventions targeting mental health ‘disorders’ (e.g. McPherson, Reference McPherson2012; Meffert and Ekblad, Reference Meffert and Ekblad2013; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a, Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon, Gordon, O'Callaghan, Papola, Peltonen, Punamaki, Richards, Staples, Unterhitzenberger, van Ommeren, De Jong, Jordans, Tol and Barbui2018b; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Vidgen and Roberts2018; Yohannan and Carlson, Reference Yohannan and Carlson2019) and/or to controlled or randomised controlled trials at the exclusion of other research designs (e.g. Brown et al., Reference Brown, de Graaf, Annan and Betancourt2017; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gross, Betancourt, Bolton, Bonetto, Gastaldon, Gordon, O'Callaghan, Papola, Peltonen, Punamaki, Richards, Staples, Unterhitzenberger, van Ommeren, De Jong, Jordans, Tol and Barbui2018b; Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Felix and Dickson2019). Reviews with a wider scope (e.g. Gouweloos et al., Reference Gouweloos, Dückers, Te Brake, Kleber and Drogendjik2014; Pedersen et al., Reference Pedersen, Kienzler and Guzder2015; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Pigott and Tol2016; Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Felix and Dickson2019; Dickson and Bangpan, Reference Dickson and Bangpan2018; Haroz et al., Reference Haroz, Nguyen, Lee, Tol, Fine and Bolton2020) have not combined their findings with an analysis of how this research has been taken up in policy and practice.

Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Barbui, Galappatti, Silove, Betancourt, Souza, Golaz and van Ommeren2011a) concluded that little of the research focused on MHPSS interventions generated between 2000 and 2010 had been translated to practice and there was an urgent need to understand approaches that were commonly used in practice and that target the broad MHPSS needs of those affected by humanitarian crises. This would require close collaboration between researchers and practitioners, attention to sociocultural context, and amplifying the voice of those directly affected by humanitarian crises. Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Patel, Tomlinson, Baingana, Galappatti, Panter-Brick, Sondorp, Wessells and van Ommeren2011b) subsequently defined a consensus-based MHPSS research agenda including 10 priority research questions to guide the field and advance research to inform practice.

The review presented here was subsequently commissioned by Elrha to examine the extent to which MHPSS research generated since 2010 has contributed to the public health evidence base and how this has influenced and impacted programming and policy in humanitarian settings. In this paper, we present findings from two areas of inquiry from this review: how knowledge on MHPSS interventions researched in humanitarian settings has advanced in the past 10 years and how the evidence has been adopted into policy and practice at various levels of the humanitarian system.

Methods

The review used mixed methods to identify the facilitating and inhibiting factors for the two areas of inquiry and to understand the broader context in which knowledge is generated and taken up.

Literature review

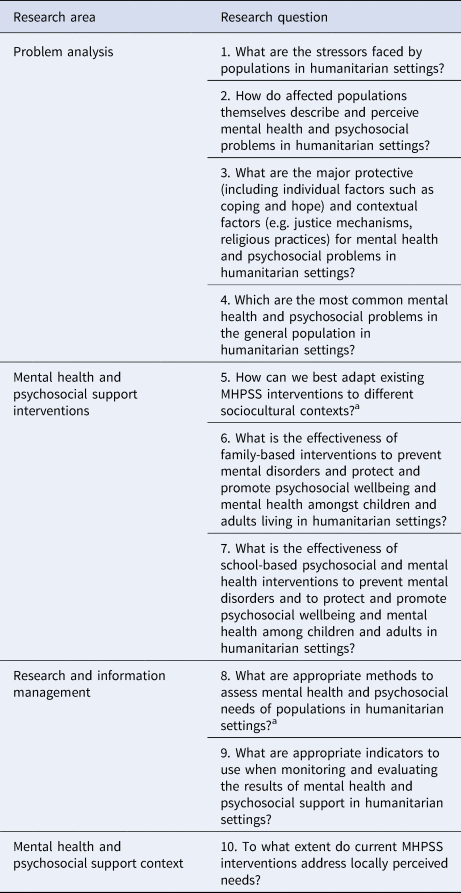

The team conducted a scoping literature review informed by the review questions in Table 1.

Table 1. Review questions

Selection criteria included studies published between January 2010 and April 2020 that described the testing, trialling or evaluation of MHPSS interventions delivered in humanitarian settings that were not focused on mental disorders (e.g. PTSD, depression). As noted in the introduction, in reality most MHPSS programmes do not target people with a diagnosable mental disorder. We wanted to understand the scope and range of research on MHPSS interventions that do not set out to treat mental disorders – e.g., those interventions that are used more in practice.

Studies were included on interventions that targeted non-specific psychological distress or wellbeing and other related psychosocial outcomes as their primary outcome measures (or, for qualitative studies, as their primary focus). In addition, studies were included on interventions that were explicit in not targeting people meeting criteria for a mental disorder, even if scales for mental disorders were included as outcome measures, as long as the study was not looking for clinical change on these measures.

Interventions included those integrated into basic humanitarian service provision, activities focused on community and family support, and psychological or social activities, provided in order to achieve MHPSS-related outcomes. Studies had to be based in lower-income countries or lower-middle income countries, in the context of a humanitarian response by governmental or non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to address the immediate impacts, aftermath or consequences of an emergency, including war, conflict, natural disaster and epidemic. The MHPSS interventions identified in the study targeted adults, children and/or adolescents. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Intervention outcome studies and studies focusing on participant experiences (including from process evaluations) were included. Where a purely quantitative design was used to measure outcomes, including experimental, quasi-experimental and prospective cohort studies, only controlled designs were included. Comparison groups could be those with no intervention, on a waiting list, other active interventions or usual care. Qualitative and mixed-methods studies were included even where the quantitative component had no pre-test or control group.

The following international databases were searched: PsycINFO (peer-reviewed), Medline, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library and Google Scholar. The search terms, as set out in Table 3, were adapted as appropriate to the syntax of each database (see Table 4 for example search strategy and tables of search terms; Nemiro et al., Reference Nemiro, Jones, Tulloch and Snider2021). When searching academic literature, the bibliographies of relevant studies were reviewed through ancestor searching and snowballing of sources. The reference lists of recent, relevant systematic reviews that included literature published since 2010 were hand-searched.

Table 3. Search terms

Table 4. Example search strategy

TS includes title, abstract and key words.

The grey literature search included the resources or publications section of the websites of 27 organisations and agencies working on MHPSS in emergencies (Nemiro et al., Reference Nemiro, Jones, Tulloch and Snider2021), the Intervention Journal website and four other specialist research websites (socialprotection.org, MHPSS.net, mhinnovation.net and the Regional Psychosocial Support Initiative). The resource pages of all websites were searched for ‘mental health’, ‘psychological’, ‘psychosocial’.

Sources were imported into a citation management software to facilitate inventory, cross-checking, removal of duplications and for further screening. The review team screened titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria, to identify potentially eligible studies for which the full paper was retrieved. One reviewer screened titles and abstracts to select full papers and a second reviewer checked the abstract of papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria and reviewed the full paper if it was not clear from the abstract. Full papers were screened and identified for inclusion by one reviewer, and a second reviewer independently screened 25% of papers. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved.

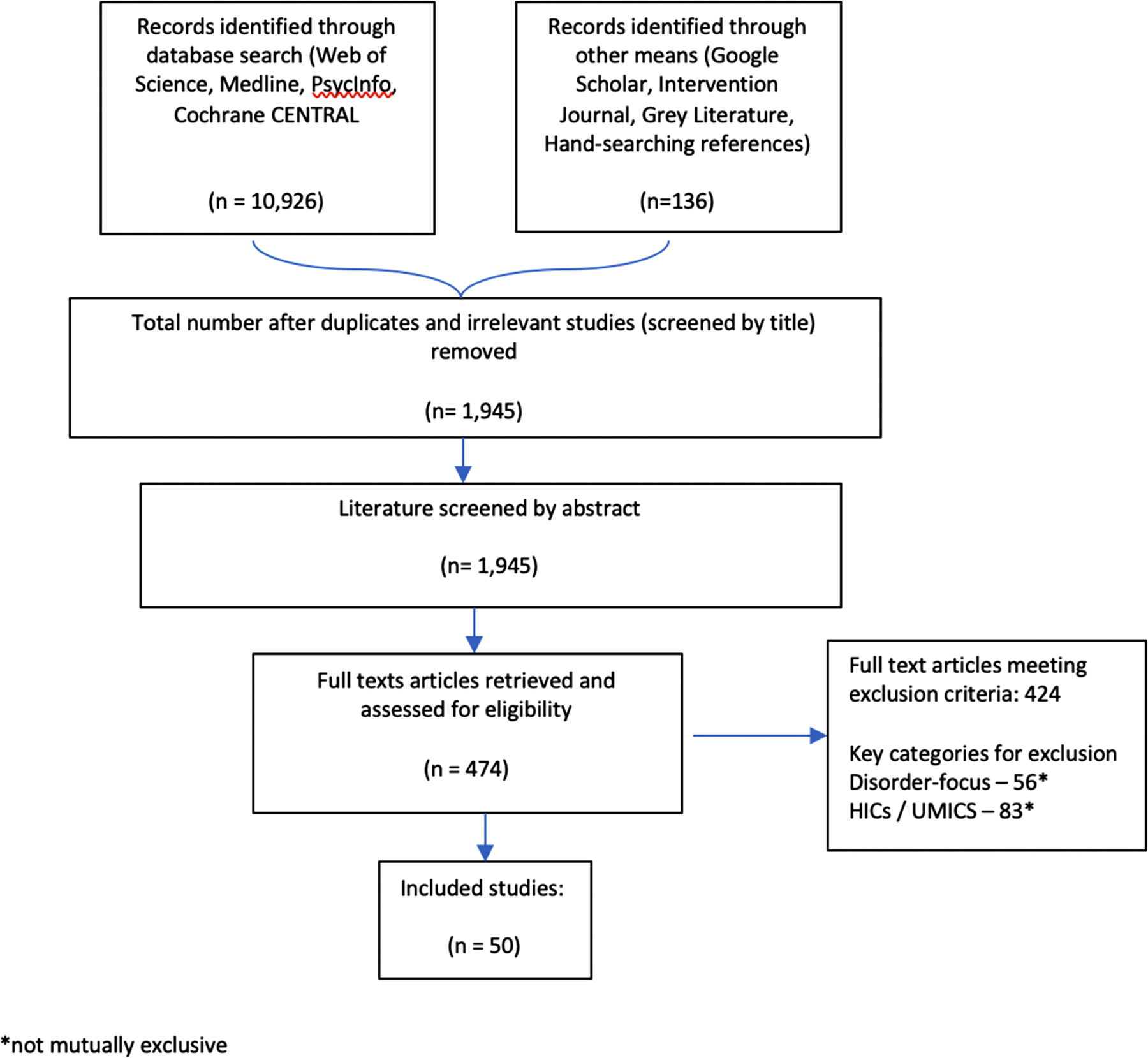

A data extraction matrix was developed based on the review questions in Fig. 1 and was piloted using a random sample of five articles and revised accordingly. The data of all pre-selected full-text sources were extracted. Data were synthesised into summary data tables to help illustrate the results of individual studies. A narrative synthesis of the findings was structured according to the study aims and review questions.

Fig. 1. Flow of studies.

The review aimed to capture a broad landscape of existing evidence, which meant including studies that may be excluded from formal systematic literature reviews. Nevertheless, a quality appraisal process was applied to all selected studies. The rigour of studies exploring participants experiences and perspectives using qualitative methods was assessed according to the methodological criterion used by Bangpan et al. (Reference Bangpan, Dickson, Chiumento and Felix2017) who re-purposed EEPI-Centre tools (Hurley et al., Reference Hurley, Dickson, Walsh, Hauari, Grant, Cumming and Oliver2013; Brunton et al., Reference Brunton, Dickson, Khatwa, Caird, Olivers, Hinds and Thomas2016; Hurley et al., Reference Hurley, Dickson, Hallett, Grant, Hauari, Walsh, Stansfield and Oliver2018) to assess the quality of study designs in a large-scale MHPSS systematic review process. Risk of bias was assessed in the RCTs and controlled before-and-after studies, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., Reference Higgins, Altman, Gotzsche, Juni, Mher, Xman, Savoic, Schulz, Weeks and Sterne2011). For the studies using a cohort design, an adaptation of the Newcastle-Ottowa Scale (Wells et al., Reference Wells, Shea, O'Connell, Peterson, Welch, Losos and Tugwell2019) was used to review quality.

Consultation

The consultation process included key informant interviews and an online survey. It aimed to assess uptake of the studies reviewed; to contribute to analysis of the status of current MHPSS intervention research; to better understand knowledge transfer, use and impact; to analyse new dimensions for research; and to produce user-centred recommendations for research to better support humanitarian practice.

Based on the literature review and overall study objectives, the research team drafted a topic guide (Nemiro et al., Reference Nemiro, Jones, Tulloch and Snider2021) as a platform for designing specific interview and survey tools for data collection. The tools were also informed by Elrha R2HC programme's four research impact areas: conceptual impact, instrumental impact, capacity and enduring connectivity (Tilley et al., Reference Tilley, Ball and Cassidy2018). The research tools were designed to be cross-cutting, include key profession-specific questions and tailored to the context of the research sites and the target groups being engaged. Key informant interviews followed a semi-structured interview guide. Questions were reviewed and refined during data collection in response to themes arising during the interviews. An online survey was created using Google Forms, with check boxes to record the majority of answers, although certain questions allowed for more detailed qualitative responses.

The sampling of interview participants was purposive and designed to reflect various professional, geographical and gender configurations that well represent this group of informants. The online survey was shared widely through platforms and resource hubs with MHPSS researchers and practitioners (e.g. through MHPSS.net and mhinnovation.net) with the aim of capturing a cross-section of these two participant groups. The final sample included 19 key informant interview participants, which took place between May and June 2020 (two key informants requested to be interviewed together), and 52 survey respondents (see Table 5 for full listing).

Table 5. Consultation data collection method, number of respondents

Two researchers conducted the qualitative key informant interviews via Zoom, one leading the interview using the voice function (i.e. without video), and a second taking detailed notes of the interview content (also without video). Questions and answers were transcribed during the interview, cross-referenced with the sound recording to ensure clarity and annotated with comments and analysis.

The quantitative survey data were analysed using descriptive statistics on Excel software. Thematic analysis was used for the qualitative data. A coding scheme was developed based on the broad themes of the topic guide and from the initial hand coding of the interview data. This involved systematically sorting through the data, labelling ideas and phenomena as they appeared and reappeared. The researchers trialled the coding scheme to isolate discrepancies and revised the scheme accordingly. All interview data were coded and analysed, with the coded transcripts being reviewed by a second researcher. The trends that emerged were critically analysed according to the study's aims.

Ethics approval

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Board of the London School of Economics (#2090). Informed consent was obtained from key informants and survey respondents, including the consent to use anonymised quotes in reporting and publications.

Results

A total of 11062 references were generated from the searches. After excluding duplicates and screening from title and abstract, the full-text reports of 737 remaining citations were retained and screened. A total of 50 research studies were included in the final review, of which one contributed to two study reports from two different data pools (Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, Brennan, Weisz and Hansen2014; McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Kellie, Kamara, Solomon, Kim and Betancourt2015). Of the studies included, 20 presented data on participant experiences/perspectives (including from process evaluations) using mixed-methods and qualitative data, and 30 were focused on outcomes, using primarily quantitative data. See Fig. 1 for the flow of studies through the review.

The majority of studies looking at participant experiences and perspectives (including process evaluations) (Barron and Abdullah, Reference Barron and Abdullah2012; Walstrom et al., Reference Walstrom, Operario, Zlotnick, Mutimura, Benekigeri and Cohen2012; Richters et al., Reference Richters, Rutayisire and Slegh2013; Eyber et al., Reference Eyber, Bermudez, Vojta, Savage and Bengehya2014; Hogwood et al., Reference Hogwood, Auerbach, Munderere and Kambibi2014; Lilley et al., Reference Lilley, Atrooshi, Metzler and Ager2014; McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Kellie, Kamara, Solomon, Kim and Betancourt2015; Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Snider and Sammour2015; Aldersey et al., Reference Aldersey, Turnbull and Turnbull2016; Eiling et al., Reference Eiling, Van Diggele-Holtland, Van Yperen and Boer2016; El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Cartwright, Redmond and Calam2016; Hechanova et al., Reference Hechanova, Waelde and Ramos2016; Hugelius et al., Reference Hugelius, Gifford, Ortenwall and Adolfsson2016; Asghar et al., Reference Asghar, Mayevskaya, Sommer, Razzaque, Laird, Khan, Qureshi, Falb and Stark2018; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Leku, Adaku, Brown, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White, Kogan, Bryant and van Ommeren2018b; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Rees, Likindikoki, Bonz, Joscelyne, Kaysen, Nixon, Njau, Tankink, Tiwari, Ventevogel, Mbwambo and Tol2019; King, Reference King2019; Koegler et al., Reference Koegler, Kennedy, Mrindi, Bachunguye, Winch, Ramazani, Makambo and Glass2019; Ordóñez-Carabaño et al., Reference Ordóñez-Carabaño, Prieto-Ursúa and Dushimimana2019; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Thorn, Amin, Mason, Lue and Nawzir2019) were scored as either ‘high’ or ‘medium’ for reliability and usefulness. Across the RCTs (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe and Tol2010; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, Brennan, Weisz and Hansen2014; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013; Lykes and Crosby, Reference Lykes and Crosby2014; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, Branham, Shannon, Betancourt, Dempster and McMullen2014; Aber et al., Reference Aber, Starkley, Tubbs, Torrente, Johnston and Wolf2015; Blattman et al., Reference Blattman, Jamison and Sheridan2015; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Green, Chase, Sim, Zayzay, Friis, Garcia-Rolland and Boone2015; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Puvimanasinghe and Price, Reference Puvimanasinghe and Price2016; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani and Awan2016; Hallman et al., Reference Hallman, Guimond, Özler and Kelvin2018; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Dherani, Chiumento, Atif, Bristow, Sikander and Rahman2017; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Leku, Adaku, Brown, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White, Kogan, Bryant and van Ommeren2018b; Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Horn, Esliker, O'May, Reiffers, Ruttenberg, Stam, de Jong and Ager2020; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Ager, Bizouerne, Byrant, Chammay, Colebunders, Gracía-Moreno, Hamdani, James, Jansen, Leku, Likindikoki, Panter-Brick, Pluess, Robinson, Ruttenberg, Savage, Welton-Mitchell, Hall, Shehadeh, Harmer and van Ommeren2020a, Reference Tol, Leku, Lakin, Carswell, Augustinavicius, Adaku, Au, Brown, Bryant, Garcia-Moreno, Musci, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2020b), there was a predominance towards a low risk of bias for each of the domains scored, except for allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, and allocation concealment, which were more ‘unclear’. There was a much higher risk of bias and a greater lack of clarity amongst the 12 controlled before-and-after studies (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Akesson, Stark, Flouri, Okot, McCollister and Boothby2011; Sonderegger et al., Reference Sonderegger, Rombouts, Ocen and McKeever2011; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Jones, Berrino, Jordans, Okema and Crow2012; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Tol, Ndayisaba and Komproe2013; Mpande et al., Reference Mpande, Higson-Smith, Chimatira, Kadaira, Mashonganyika, Ncube, Ngwenya, Vinson, Wild and Ziwoni2013; Mercy Corps, 2015; Uyun and Witruk, Reference Uyun and Witruk2017; Akiyama et al., Reference Akiyama, Gregorio and Kobayashi2018; Veronese and Barola, Reference Veronese and Barola2018; Metzler et al., Reference Metzler, Diaconu, Hermosilla, Kaijuka, Ebulu, Savage and Alger2019a, Reference Metzler, Jonfa, Savage and Ager2019b; Ziveri et al., Reference Ziveri, Kiani and Broquet2019). Aside from risk of bias, six of the RCTs and controlled before-and-after designs (Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Tol, Ndayisaba and Komproe2013; Blattman et al., Reference Blattman, Jamison and Sheridan2015; Puvimanasinghe and Price, Reference Puvimanasinghe and Price2016; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani and Awan2016; Veronese and Barola, Reference Veronese and Barola2018; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Dherani, Chiumento, Atif, Bristow, Sikander and Rahman2017) had an additional qualitative component which increased their usefulness. Amongst the two cohort studies (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Stark, Olsen, Wessells and Boothby2010; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Veale, Worthen and Wessells2011), one received an overall fair quality score, and another received a poor-quality score.

Synthesised findings from the review and consultation

These findings are synthesised from the literature review and insights from the consultation process to answer two broad questions: (1) How has knowledge on MHPSS interventions researched in humanitarian settings advanced in the past 10 years? And (2) How has MHPSS intervention research been taken up in policy and practice at various levels of the humanitarian system? To answer these questions within the frame of the data collected, the results are structured around seven core themes that emerged from the literature and the consultation process. The core themes that emerged to answer question one include (1) an unbalanced evidence base, (2) a broadening in scope, but with mismatched outcome measures and (3) the influence of the RCT. The core themes that emerged to answer question two include (4) some progress in policy and practice, (5) a geographic divide between decision-making and locally perceived needs, (6) a disconnection of country-level MHPSS practitioners and (7) hindrances to uptake.

(1) An unbalanced evidence base

There was a geographic emphasis in the literature towards East, West and Central Africa, where two-thirds of the studies reported were located (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Stark, Olsen, Wessells and Boothby2010, Reference Ager, Akesson, Stark, Flouri, Okot, McCollister and Boothby2011; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Veale, Worthen and Wessells2011; Sonderegger et al., Reference Sonderegger, Rombouts, Ocen and McKeever2011; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Jones, Berrino, Jordans, Okema and Crow2012; Walstrom et al., Reference Walstrom, Operario, Zlotnick, Mutimura, Benekigeri and Cohen2012; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Tol, Ndayisaba and Komproe2013; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013, Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Richters et al., Reference Richters, Rutayisire and Slegh2013; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, Brennan, Weisz and Hansen2014; Eyber et al., Reference Eyber, Bermudez, Vojta, Savage and Bengehya2014; Lykes and Crosby, Reference Lykes and Crosby2014; Hogwood et al., Reference Hogwood, Auerbach, Munderere and Kambibi2014; Aber et al., Reference Aber, Starkley, Tubbs, Torrente, Johnston and Wolf2015; Blattman et al., Reference Blattman, Jamison and Sheridan2015; McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Kellie, Kamara, Solomon, Kim and Betancourt2015; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Green, Chase, Sim, Zayzay, Friis, Garcia-Rolland and Boone2015; Aldersey et al., Reference Aldersey, Turnbull and Turnbull2016; Eiling et al., Reference Eiling, Van Diggele-Holtland, Van Yperen and Boer2016; Hallman et al., Reference Hallman, Guimond, Özler and Kelvin2018; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2018a, Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Leku, Adaku, Brown, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White, Kogan, Bryant and van Ommeren2018b; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Rees, Likindikoki, Bonz, Joscelyne, Kaysen, Nixon, Njau, Tankink, Tiwari, Ventevogel, Mbwambo and Tol2019; King, Reference King2019; Ordóñez-Carabaño et al., Reference Ordóñez-Carabaño, Prieto-Ursúa and Dushimimana2019; Koegler et al., Reference Koegler, Kennedy, Mrindi, Bachunguye, Winch, Ramazani, Makambo and Glass2019; Metzler et al., Reference Metzler, Diaconu, Hermosilla, Kaijuka, Ebulu, Savage and Alger2019a, Reference Metzler, Jonfa, Savage and Ager2019b; Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Horn, Esliker, O'May, Reiffers, Ruttenberg, Stam, de Jong and Ager2020; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Ager, Bizouerne, Byrant, Chammay, Colebunders, Gracía-Moreno, Hamdani, James, Jansen, Leku, Likindikoki, Panter-Brick, Pluess, Robinson, Ruttenberg, Savage, Welton-Mitchell, Hall, Shehadeh, Harmer and van Ommeren2020a, Reference Tol, Leku, Lakin, Carswell, Augustinavicius, Adaku, Au, Brown, Bryant, Garcia-Moreno, Musci, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2020b). Despite considerable humanitarian work occurring in the Middle East and in Asia (the latter generally characterised by natural disasters), these settings had relatively limited representation in the literature.

The most commonly researched interventions were at the group level (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Stark, Olsen, Wessells and Boothby2010, Reference Ager, Akesson, Stark, Flouri, Okot, McCollister and Boothby2011; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe and Tol2010; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Veale, Worthen and Wessells2011; Sonderegger et al., Reference Sonderegger, Rombouts, Ocen and McKeever2011; Barron and Abdullah, Reference Barron and Abdullah2012; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Jones, Berrino, Jordans, Okema and Crow2012; Walstrom et al., Reference Walstrom, Operario, Zlotnick, Mutimura, Benekigeri and Cohen2012; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Tol, Ndayisaba and Komproe2013; Mpande et al., Reference Mpande, Higson-Smith, Chimatira, Kadaira, Mashonganyika, Ncube, Ngwenya, Vinson, Wild and Ziwoni2013; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013, Reference O'Callaghan, Branham, Shannon, Betancourt, Dempster and McMullen2014, Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Richters et al., Reference Richters, Rutayisire and Slegh2013; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, Brennan, Weisz and Hansen2014; Eyber et al., Reference Eyber, Bermudez, Vojta, Savage and Bengehya2014; Hogwood et al., Reference Hogwood, Auerbach, Munderere and Kambibi2014; Lykes and Crosby, Reference Lykes and Crosby2014; Lilley et al., Reference Lilley, Atrooshi, Metzler and Ager2014; Aber et al., Reference Aber, Starkley, Tubbs, Torrente, Johnston and Wolf2015; Blattman et al., Reference Blattman, Jamison and Sheridan2015; McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Kellie, Kamara, Solomon, Kim and Betancourt2015; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Green, Chase, Sim, Zayzay, Friis, Garcia-Rolland and Boone2015; Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Snider and Sammour2015; Mercy Corps, 2015; Aldersey et al., Reference Aldersey, Turnbull and Turnbull2016; Eiling et al., Reference Eiling, Van Diggele-Holtland, Van Yperen and Boer2016; Hechanova et al., Reference Hechanova, Waelde and Ramos2016; Uyun and Witruk, Reference Uyun and Witruk2017; Akiyama et al., Reference Akiyama, Gregorio and Kobayashi2018; Hallman et al., Reference Hallman, Guimond, Özler and Kelvin2018; Asghar et al., Reference Asghar, Mayevskaya, Sommer, Razzaque, Laird, Khan, Qureshi, Falb and Stark2018; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2018a, Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Leku, Adaku, Brown, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White, Kogan, Bryant and van Ommeren2018b; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Rees, Likindikoki, Bonz, Joscelyne, Kaysen, Nixon, Njau, Tankink, Tiwari, Ventevogel, Mbwambo and Tol2019; King, Reference King2019; Ordóñez-Carabaño et al., Reference Ordóñez-Carabaño, Prieto-Ursúa and Dushimimana2019; Koegler et al., Reference Koegler, Kennedy, Mrindi, Bachunguye, Winch, Ramazani, Makambo and Glass2019; Metzler et al., Reference Metzler, Diaconu, Hermosilla, Kaijuka, Ebulu, Savage and Alger2019a, Reference Metzler, Jonfa, Savage and Ager2019b; Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Horn, Esliker, O'May, Reiffers, Ruttenberg, Stam, de Jong and Ager2020; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Ager, Bizouerne, Byrant, Chammay, Colebunders, Gracía-Moreno, Hamdani, James, Jansen, Leku, Likindikoki, Panter-Brick, Pluess, Robinson, Ruttenberg, Savage, Welton-Mitchell, Hall, Shehadeh, Harmer and van Ommeren2020a, Reference Tol, Leku, Lakin, Carswell, Augustinavicius, Adaku, Au, Brown, Bryant, Garcia-Moreno, Musci, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2020b) with individual (Blattman et al., Reference Blattman, Jamison and Sheridan2015; Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Snider and Sammour2015; Puvimanasinghe and Price, Reference Puvimanasinghe and Price2016; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani and Awan2016; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Rees, Likindikoki, Bonz, Joscelyne, Kaysen, Nixon, Njau, Tankink, Tiwari, Ventevogel, Mbwambo and Tol2019; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Thorn, Amin, Mason, Lue and Nawzir2019) and school-wide (Aber et al., Reference Aber, Starkley, Tubbs, Torrente, Johnston and Wolf2015; Akiyama et al., Reference Akiyama, Gregorio and Kobayashi2018; Veronese and Barola, Reference Veronese and Barola2018) interventions the least researched. Interventions predominantly targeted adults, with limited direct evidence on outcomes for children and adolescents and no specific attention to whole family approaches. Where family-focused interventions were used, the interventions were primarily directed at parents and caregivers (e.g. parenting skills) and did not engage the whole family.

A small number of the studies reviewed integrated MHPSS within other technical areas; the most common were MHPSS-child protection (McKay et al., Reference McKay, Veale, Worthen and Wessells2011; Eyber et al., Reference Eyber, Bermudez, Vojta, Savage and Bengehya2014; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Asghar et al., Reference Asghar, Mayevskaya, Sommer, Razzaque, Laird, Khan, Qureshi, Falb and Stark2018; Mercy Corps, 2015; Hallman et al., Reference Hallman, Guimond, Özler and Kelvin2018; Metzler et al., Reference Metzler, Diaconu, Hermosilla, Kaijuka, Ebulu, Savage and Alger2019a, Reference Metzler, Jonfa, Savage and Ager2019b), MHPSS-economic support (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Stark, Olsen, Wessells and Boothby2010; Lilley et al., Reference Lilley, Atrooshi, Metzler and Ager2014; Aldersey et al., Reference Aldersey, Turnbull and Turnbull2016; Hallman et al., Reference Hallman, Guimond, Özler and Kelvin2018; Koegler et al., Reference Koegler, Kennedy, Mrindi, Bachunguye, Winch, Ramazani, Makambo and Glass2019) and MHPSS-GBV (Gender-Based Violence) (O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013; Richters et al., Reference Richters, Rutayisire and Slegh2013; Hallman et al., Reference Hallman, Guimond, Özler and Kelvin2018; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Rees, Likindikoki, Bonz, Joscelyne, Kaysen, Nixon, Njau, Tankink, Tiwari, Ventevogel, Mbwambo and Tol2019; Koegler et al., Reference Koegler, Kennedy, Mrindi, Bachunguye, Winch, Ramazani, Makambo and Glass2019). The nature of what counted as ‘integration’ varied across these studies and included those that incorporated programmatic components usually seen in another sector into their intervention design (e.g. the MHPSS-economic support studies integrated cash, economic support and group fund-shares into the interventions). Key informants also noted a lack of research on longer-term integrated MHPSS programming that addresses the most pressing and urgent humanitarian priorities (e.g. cash, shelter, food distribution and livelihoods).

Apart from a number of interventions for Child/Youth Friendly Spaces (Eyber et al., Reference Eyber, Bermudez, Vojta, Savage and Bengehya2014; Mercy Corps, Reference Meyer and Morand2015; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Metzler et al., Reference Metzler, Diaconu, Hermosilla, Kaijuka, Ebulu, Savage and Alger2019a, Reference Metzler, Jonfa, Savage and Ager2019b), there were minimal replications of the same approach in different settings in the literature reviewed. A relatively low proportion of the studies examined long-term impacts of the interventions with follow-up data collection or, if the follow-up did occur, this was not reflected in the literature. However, a significant proportion of interventions were adapted to the specific sociocultural context before being tested. Most of the studies reviewed used adapted assessment tools, actively adapted assessment tools or created new assessment tools to fit the setting and context, while a number of the studies described the development of locally relevant tools and incorporated these into their assessment processes.

Amongst the two research priorities developed by Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Barbui, Galappatti, Silove, Betancourt, Souza, Golaz and van Ommeren2011a, Reference Tol, Patel, Tomlinson, Baingana, Galappatti, Panter-Brick, Sondorp, Wessells and van Ommeren2011b) that were observable in the scope of this study (see Table 6), the literature review highlighted encouraging progress on research that adapts interventions to the sociocultural context (priority 5). However, the literature review and consultation process emphasised a continued lack of studies focusing on family-based interventions that measure family-oriented outcomes (priority 6) and school-based interventions to prevent, protect and promote psychosocial wellbeing and mental health among children and adults (priority 7). The body of MHPSS intervention research reviewed also did not consistently measure the appropriateness of its methods of assessing need (priority 8), nor did it show how interventions were explicitly responding to locally perceived needs (priority 10).

(2) A broadening in scope, but with mismatched outcome measures

Table 6. Priority research questions (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Patel, Tomlinson, Baingana, Galappatti, Panter-Brick, Sondorp, Wessells and van Ommeren2011b)

a Indicates the research priority was observable in the scope of this study.

The conclusions of key informants pointed to a broadening in scope and range of research over the last 10 years. Moving from a focus mostly on mental disorders and ‘dysfunction’ to using more positive outcome measures of mental health and psychosocial wellbeing that give greater attention to context. The literature review found that a total of 23 of the interventions studied were described as purely focused on promoting wellbeing/resilience (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Stark, Olsen, Wessells and Boothby2010, Reference Ager, Akesson, Stark, Flouri, Okot, McCollister and Boothby2011, Reference Aber, Starkley, Tubbs, Torrente, Johnston and Wolf2015; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Veale, Worthen and Wessells2011; Eyber et al., Reference Eyber, Bermudez, Vojta, Savage and Bengehya2014; Hogwood et al., Reference Hogwood, Auerbach, Munderere and Kambibi2014; Mercy Corps, 2015; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Green, Chase, Sim, Zayzay, Friis, Garcia-Rolland and Boone2015; Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Snider and Sammour2015; Hechanova et al., Reference Hechanova, Waelde and Ramos2016; McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Kellie, Kamara, Solomon, Kim and Betancourt2015; Eiling et al., Reference Eiling, Van Diggele-Holtland, Van Yperen and Boer2016; Akiyama et al., Reference Akiyama, Gregorio and Kobayashi2018; Asghar et al., Reference Asghar, Mayevskaya, Sommer, Razzaque, Laird, Khan, Qureshi, Falb and Stark2018; Hallman et al., Reference Hallman, Guimond, Özler and Kelvin2018; Veronese and Barola, Reference Veronese and Barola2018; King, Reference King2019; Koegler et al., Reference Koegler, Kennedy, Mrindi, Bachunguye, Winch, Ramazani, Makambo and Glass2019; Ordóñez-Carabaño et al., Reference Ordóñez-Carabaño, Prieto-Ursúa and Dushimimana2019; Metzler et al., Reference Metzler, Diaconu, Hermosilla, Kaijuka, Ebulu, Savage and Alger2019a, Reference Metzler, Jonfa, Savage and Ager2019b; Sijbrandij et al., Reference Sijbrandij, Horn, Esliker, O'May, Reiffers, Ruttenberg, Stam, de Jong and Ager2020), 18 were described as focusing on both promoting wellbeing/resilience and reducing suffering/dysfunction (Sonderegger et al., Reference Sonderegger, Rombouts, Ocen and McKeever2011; Barron and Abdullah, Reference Barron and Abdullah2012; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Jones, Berrino, Jordans, Okema and Crow2012; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Tol, Ndayisaba and Komproe2013; Mpande et al., Reference Mpande, Higson-Smith, Chimatira, Kadaira, Mashonganyika, Ncube, Ngwenya, Vinson, Wild and Ziwoni2013; Richters et al., Reference Richters, Rutayisire and Slegh2013; Lilley et al., Reference Lilley, Atrooshi, Metzler and Ager2014; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, Branham, Shannon, Betancourt, Dempster and McMullen2014; Aldersey et al., Reference Aldersey, Turnbull and Turnbull2016; El-Khani et al., Reference El-Khani, Cartwright, Redmond and Calam2016; Puvimanasinghe and Price, Reference Puvimanasinghe and Price2016; Hugelius et al., Reference Hugelius, Gifford, Ortenwall and Adolfsson2016; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Dherani, Chiumento, Atif, Bristow, Sikander and Rahman2017; Uyun and Witruk, Reference Uyun and Witruk2017; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2018a, Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Leku, Adaku, Brown, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White, Kogan, Bryant and van Ommeren2018b; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Rees, Likindikoki, Bonz, Joscelyne, Kaysen, Nixon, Njau, Tankink, Tiwari, Ventevogel, Mbwambo and Tol2019; Ziveri et al., Reference Ziveri, Kiani and Broquet2019), and nine were focused on only reducing suffering/dysfunction (Walstrom et al., Reference Walstrom, Operario, Zlotnick, Mutimura, Benekigeri and Cohen2012; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, Brennan, Weisz and Hansen2014; Lykes and Crosby, Reference Lykes and Crosby2014; Blattman et al., Reference Blattman, Jamison and Sheridan2015; Rahman et al., Reference Rahman, Hamdani and Awan2016; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Dherani, Chiumento, Atif, Bristow, Sikander and Rahman2017; Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2018a; Sullivan et al., Reference Sullivan, Thorn, Amin, Mason, Lue and Nawzir2019). Key informants also noted an increased interest in research on the determinants of mental health and psychosocial wellbeing (e.g. poverty, GBV, marginalisation). This shift in research focus was felt to mirror the shift in practice at the global level and was expected to continue.

A key informant (Re 5) stated,

‘I anticipate a big shift…[to continue] over the next 10 years. The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health was clear on that. Taking a full spectrum approach, moving away from the dichotomy of disorder versus non-disorder, but I think we are at the beginning of that. I think the research domain, if you aware of looking at MHPSS as a continuum, has been dominated by the ‘MH’ part…In fact, we are now putting a number of proposals together that are looking at issues of social connectedness, much more mechanistic outcomes, for example understanding the interplay between social determinants and mental health. That is part of the shift we are all in.’

However, a disconnect was identified in many of the studies reviewed, whereby the interventions were broad, community-based and geared towards positive outcomes, but the outcome measures used focused only on changes in symptoms of mental disorder. In several cases, there was a mismatch between the stated intervention aims and the focus of the research (including selected outcome measures). For example, in 12 studies (Eyber et al., Reference Eyber, Bermudez, Vojta, Savage and Bengehya2014; Aber et al., Reference Aber, Starkley, Tubbs, Torrente, Johnston and Wolf2015; Mercy Corps, 2015; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Green, Chase, Sim, Zayzay, Friis, Garcia-Rolland and Boone2015; Schafer et al., Reference Schafer, Snider and Sammour2015; Asghar et al., Reference Asghar, Mayevskaya, Sommer, Razzaque, Laird, Khan, Qureshi, Falb and Stark2018; Hallman et al., Reference Hallman, Guimond, Özler and Kelvin2018; Veronese and Barola, Reference Veronese and Barola2018; Koegler et al., Reference Koegler, Kennedy, Mrindi, Bachunguye, Winch, Ramazani, Makambo and Glass2019; Metzler et al., Reference Metzler, Diaconu, Hermosilla, Kaijuka, Ebulu, Savage and Alger2019a, Reference Metzler, Jonfa, Savage and Ager2019b), the intervention was described as purely focused on promoting wellbeing/resilience, and yet the research design included a focus on suffering/dysfunction. Key informants explained the previous focus on symptoms and disorders as related to the historical roots of MHPSS from medicine and psychiatry; the existing, validated measurement tools being mostly disorder-focused, which lend themselves better to RCTs; and the primary biomedical paradigm of certain high-impact academic journals.

(3) The influence of the RCT

Having RCTs that demonstrate the effectiveness of MHPSS interventions was seen by key informants as advancing the field: ‘everyone loves an RCT, it adds an extra level of credibility to interventions’ (Pr 1). Indeed, amongst the new interventions that have been adopted into MHPSS practice (see below), many have been researched through RCTs, indicating the influence of these research designs. The limitations of this research design were also acknowledged by key informants, for example, being less readily applied to community-focused interventions that address difficult-to-measure changes and complex social dynamics. The literature review confirmed that person-focused psychological interventions have been disproportionately studied through RCTs, whereas community-focused interventions, including reintegration programmes, reconciliation and healing interventions, community-led support and community support groups, were less likely to have a controlled design. A risk associated with this was noted by one global coordinator:

‘RCTs are good for studying certain sorts of problems and interventions. This creates a bias around what studies are included in systematic reviews, which skews your view of what works.’ (Co 1)

Although key informants agreed that RCTs are important to demonstrate effectiveness, given the controlled conditions required for an RCT, many felt that other types of research design are required to understand how an intervention works in real-world programme implementation. MHPSS evidence generated more recently was acknowledged to include ‘a greater range of methods’, and key informants also concluded that the global MHPSS community was increasingly placing greater ‘legitimacy’ and value on qualitative research. The literature review was able to capture this broader range of designs, including controlled before-and-after studies, mixed-methods and qualitative designs.

(4) Some progress in policy and practice

The consultation process indicated that MHPSS intervention research conducted over the last 10 years has influenced programmatic changes and uptake for several interventions, particularly scalable psychological interventions and a smaller number of broader, community-based interventions. Although not all intervention research has led to continued change or new programming, the following examples identified in the literature review and by key informants have been instrumental: (1) contextual refinement and implementation of newly developed scalable psychological interventions [e.g. Self Help Plus (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Augustinavicius, Carswell, Brown, Adaku, Leku, García-Moreno, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2018a), Problem Management Plus (WHO, 2018) and Interpersonal Psychotherapy-Group (WHO and Columbia University, 2016)], (2) further development of existing interventions [e.g. Advancing Adolescents (Panter-Brick et al., Reference Panter-Brick, Dajani, Eggerman, Hermosilla, Sancilio and Ager2017) in Jordan and Syria], (3) influencing uptake and scaling of various interventions because of a supporting evidence base [e.g. informants reported that the fact that Psychological First Aid (PFA) is an ‘evidence-informed’ approach encouraged its wide uptake], and (4) re-evaluating and improving existing approaches [e.g. multi-country evaluation of child-friendly spaces (Hermosilla et al., Reference Hermosilla, Metzler, Savage, Musa and Ager2019) led to a critical re-evaluation of the approach and greater attention to quality safeguards in its implementation].

Practitioner survey respondent reported that MHPSS intervention research has also influenced their choice of specific components of MHPSS approaches (e.g. the use of lay mental health workers, a focus on coping strategies and engagement with families), even when a component was not delivered in the context of the overall intervention in which it was originally studied. Key informant practitioner key informant confirmed that research had influenced their choice of overall intervention, although they often placed greater value on locally produced information, including the routine data they collected from needs assessments, lessons learned reports, and routine monitoring and evaluation activities to influence programming. The importance of being seen to be basing programmes on evidence was also raised, and one global MHPSS coordinator (headquarter-based) key informant noted: ‘there is an urgency and desire to say we are evidence-based’ (Co1). Yet, despite progress, programmes not being based on evidence were described as the reality in many contexts: ‘a lot of NGOs run MHPSS programming that has no evidence-base’ (Re1).

At the level of global MHPSS policy, research was thought by key informants to have influenced the shift from ‘critical incident stress debriefing’ to broad endorsement of PFA, and the shift from a single focus on trauma counselling and PTSD-focused interventions to transdiagnostic and community-based interventions. Global Child Protection policy has also shifted in response to a multi-country intervention study on child-friendly spaces. There was also a reported increased focus on and allocation of resources for adapting interventions based on rigorous needs assessments, consultations with end users and engagement with community-based stakeholders. However, amongst a body of 24 global MHPSS guidelines and strategy documents reviewed as part of the literature review process, only seven of the selected studies were cited once (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Stark, Olsen, Wessells and Boothby2010; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe and Tol2010; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Jones, Berrino, Jordans, Okema and Crow2012; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013; Puffer et al., Reference Puffer, Green, Chase, Sim, Zayzay, Friis, Garcia-Rolland and Boone2015; Eiling et al., Reference Eiling, Van Diggele-Holtland, Van Yperen and Boer2016) or twice (2). In addition, 11 studies (Ager et al., Reference Ager, Stark, Olsen, Wessells and Boothby2010, Reference Ager, Akesson, Stark, Flouri, Okot, McCollister and Boothby2011; Jordans et al., Reference Jordans, Komproe and Tol2010, Reference Jordans, Tol, Ndayisaba and Komproe2013; O'Callaghan et al., Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon, Rafferty and Black2013, Reference O'Callaghan, Branham, Shannon, Betancourt, Dempster and McMullen2014, Reference O'Callaghan, McMullen, Shannon and Rafferty2015; Betancourt et al., Reference Betancourt, McBain, Newnham, Brennan, Weisz and Hansen2014; Blattman et al., Reference Blattman, Jamison and Sheridan2015; McBain et al., Reference McBain, Salhi, Hann, Kellie, Kamara, Solomon, Kim and Betancourt2015; Eiling et al., Reference Eiling, Van Diggele-Holtland, Van Yperen and Boer2016) were cited indirectly through their inclusion in systematic reviews which were referenced in the MHPSS guidelines and strategy documents.

Furthermore, only one example of an instrumental change in national government policy was reported by key informants, resulting from research conducted on the Advancing Adolescents programme in Jordan. The consultation process identified that other programme and/or policy change may have occurred without being documented or tracked as 45% (n = 9) of researchers surveyed noted that they do not systematically gather information on the changes that result from their research.

(5) A geographic divide between decision-making and locally perceived needs

Academic researchers reported being under pressure from university requirements to secure publications in highly rated academic journals (‘that does change my focus quite a bit’, Re 1), and from funders who can act as ‘arbiters’ over the final topic of research. A geographic divide was identified in the hierarchy of ideas of the ‘global north’ over the ‘global south’ and supported by structural inequalities in research funding. One national government focal person described ‘ideas coming from the North and [being] sold to professionals in the South’ (NaGov 2). The survey asked researchers for the single most important reason behind their choice of current/most recent MHPSS intervention research topic out of five options and found that 40% (n = 8) reported that personal interest/continuation of previous research was the most important influence. Key informants recognised that MHPSS intervention research topics still need to be better ‘driven by needs in the field’ and not just ‘a good idea from a researcher behind the table’ (Co 2). A shift in research being informed by local need was partially observable from the literature reviewed; however, a theme emerged from the consultation process that MHPSS intervention research still remains top-down.

(6) Disconnection of country-level MHPSS practitioners

During the interview process, the country-level based MHPSS practitioners described feeling ‘not very familiar’ (Pr3) with global research and research generated in country settings beyond their own, and none had heard of the 2010 MHPSS research priorities. This extended into a wider theme of ‘fragile knowledge’ and the disconnection of country-level based MHPSS practitioners from formal MHPSS intervention research findings. Country-level based MHPSS practitioners felt particularly disconnected from certain types of research, for example, research published primarily in academic journals: ‘Another thing – who has access to journals? Field-based practitioners don't have access’ (Co1). Although this lack of access to journals may be true for many country-based practitioners, headquarter-based key informants still reported that practice has been impacted by research, and this was further supported by survey findings.

The survey results demonstrated that 80% (n = 8) of practitioners surveyed who were based in Europe and North America rated their familiarity with MHPSS intervention research from the past 10 years as either four or five out of five, but only 36% (n = 2) of practitioners based outside of Europe and North America did so. When asked how easy it is to access MHPSS research, 60% (n = 6) of practitioners in Europe and North America reported a four or five out of five, compared to only 27% (n = 6) of those based outside Europe and North America. Ninety-four per cent (n = 30) of all practitioners agreed somewhat or very much that information is expensive or in difficult-to-access closed communities or portals. The findings indicated that the pathway that research travels through organisations and into practice is multi-layered involving several different actors at different levels, each likely engaged in their own preferred channels.

(7) Hindrances to uptake

Country-level practitioners interviewed raised concerns about their ability to interpret and think critically about MHPSS intervention research. Not possessing these skills and knowledge was thought to risk under-appreciating the significance of research generated, misreading or over-stating the significance of research generated, and mis-applying findings and recommendations.

A further limit to the knowledge brokering process was that practitioners and policymakers lacked the time to access and become familiar with research. Ninety-four per cent of the practitioners surveyed agreed somewhat or very much that they lacked time to search for and engage in research learnings. As noted by one policymaker who was interviewed, this can present a ‘Catch-22’:

‘Maybe we are also at fault as policymakers in the sense that we don't read much. We are bogged down with issues of administration, planning, but with planning we need to plan with evidence.’ (NaGo2)

The step of actively transforming and translating evidence from knowledge to practice was raised across all the stakeholder groups interviewed as being critical to the knowledge brokering process. The majority suggested that evidence products should be digestible, practical and focused on the end user, without losing the nuance of the findings. The following quotes are representative of the different stakeholder groups engaged.

‘How research findings can be digested in a way that is easy to understand and see how it related… How evidence can lead to higher quality, more effective programming.’ (Co3)

‘Key challenges with research projects and findings is the communication of them and that often they are not targeted to who needs to receive them.’ (DoG1)

‘We need to simplify the information. One-page policy brief, giving infographics if there is a need for that.’ (NaGo2)

Discussion

This study sought to answer how MHPSS interventions researched in humanitarian settings have advanced in the past 10 years and how the evidence has been adopted into policy and practice at various levels of the humanitarian system. The study was unique in that it focused on MHPSS interventions delivered in humanitarian settings that were not focused on mental disorders which allowed for a broader perspective more likely to capture interventions commonly implemented in MHPSS programming.

The literature review identified a rapidly growing evidence base that has evaluated a range of MHPSS interventions, and that gives greater attention to adapting interventions to the sociocultural context, which was one of the key research priorities identified by Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Barbui, Galappatti, Silove, Betancourt, Souza, Golaz and van Ommeren2011a, Reference Tol, Patel, Tomlinson, Baingana, Galappatti, Panter-Brick, Sondorp, Wessells and van Ommeren2011b) (priority 5, Table 6). However, there remains limited direct evidence on outcomes for children and adolescents and whole family approaches which were two further research priorities identified by Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Barbui, Galappatti, Silove, Betancourt, Souza, Golaz and van Ommeren2011a, Reference Tol, Patel, Tomlinson, Baingana, Galappatti, Panter-Brick, Sondorp, Wessells and van Ommeren2011b) (priority 6 and 7, Table 6). Few studies examined long-term impacts of interventions and there were minimal replications of the same approach that could test efficacy across settings and population groups. Key informants also noted a lack of research on longer-term integrated MHPSS programming that addresses the most pressing and urgent humanitarian priorities (e.g. cash, shelter, food distribution and livelihoods).

A general shift was identified in the consultation process away from a focus on disorder and towards the more positive aspects of wellbeing. However, there remained a mismatch in many studies included in the literature review, whereby the interventions were broad, community-based and geared towards positive outcomes, but the outcome measures used still focused on changes in symptoms of mental disorders. A number of the published studies excluded from the literature review for focusing on a clinical population reflected that they had delivered interventions with preventative or promotive objectives, but measured mental disorder symptoms and (perhaps unsurprisingly) found minimal or no change on these outcomes (e.g. Bass et al., Reference Bass, Poudyal, Tol, Murray, Nadison and Bolton2012; Kohrt et al., Reference Kohrt, Burkey, Stuart and Koirala2015; Jani et al., Reference Jani, Vu, Kay, Habtamu and Kalibala2016; Dhital et al., Reference Dhital, Shibanuma, Miyaguchi, Kiriya and Jimba2019). This mismatch has been observed in other reviews of MHPSS intervention research (Haroz et al., Reference Haroz, Nguyen, Lee, Tol, Fine and Bolton2020; Purgato et al., Reference Purgato, Gastaldon, Papola, van Ommeren, Barbui and Tol2018a ). Sometimes this may be appropriate, but more often it fails to capture the breadth of outcomes that could be generated by these types of interventions (e.g. social cohesion, social connectedness, functioning, agency) and thus restricts potential learning for programming and policy. These constructs may be more difficult to measure given the paucity of available validated scales, however progress is being made. For example, the IASC MHPSS Common Monitoring and Evaluation Framework, Version 2.0 (IASC, 2021) includes qualitative and quantitative means of verification for each impact indicator. Lessons can also be learned from research conducted in high-income countries, which have made more progress in this regard, and applied to research conducted in humanitarian settings.

Several newly implemented, scalable psychological interventions have been studied through RCTs suggesting the influence of research design on uptake. Conducting RCTs has built important credibility in the field, and this continues to be a high priority, but should not lead to exclusion of research on the types of interventions practitioners are actually implementing or want to implement. RCTs tend to focus more on person-centred interventions and individual mental health outcomes and exclude broad-based community interventions which are used more in practice (Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Dickson, Chiumento and Felix2017; Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Felix and Dickson2019). Such research can help to better understand and address the social determinants of mental health and psychosocial wellbeing such as poverty, interpersonal relationships, family dynamics and access to education (Bangpan et al., Reference Bangpan, Felix and Dickson2019). Moreover, integrated MHPSS programming that addresses the social determinants of mental health and psychosocial wellbeing is much harder to fit to an RCT mould. RCTs can also exclude more positive outcome measures of psychosocial wellbeing (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Barbui, Galappatti, Silove, Betancourt, Souza, Golaz and van Ommeren2011a, Reference Tol, Patel, Tomlinson, Baingana, Galappatti, Panter-Brick, Sondorp, Wessells and van Ommeren2011b). A balance needs to be made between rigorous research and relevant research, or we risk increasing divisions between research and practice or implementing what is measurable through an RCT, rather than what is most appropriate to the context. Key stakeholders reported the need for other types of research designs, including those which can help to understand how an intervention works in complex humanitarian settings with the myriad challenges and instability that arises. Implementation research could be one way to achieve greater reach of research to practitioners, by exploring ways to understand the realities of day-to-day roll out, the cost-effectiveness of interventions and the various approaches to measuring and maintaining quality and fidelity.

MHPSS intervention research generated in the past 10 years has informed and influenced programming in humanitarian settings, especially around the implementation of newly developed scalable psychological interventions. Survey respondents reported that MHPSS intervention research also influenced their choice of specific components of MHPSS approaches, e.g. the use of lay workers, a focus on coping strategies, etc. Over the last few years, there has also been increased focus and allocation of resources for adapting evidence-based interventions with key community stakeholders. Instrumental change was reported at the level of global MHPSS policy; however, change was rare at the level of national government policy. Considering our finding that the impact of MHPSS intervention research has not been well tracked or documented, there may be other notable changes which have not been captured (e.g. the length of time it takes for research to result in notable programmatic changes). Supporting and tracking change should be the responsibility of all parties involved in generating and using evidence-based interventions; this especially pertains to the resources allocated by donors. Adequate time and funds are needed for uptake activities on research projects, and for monitoring and evaluation of these activities against specified outcomes, to ensure tangible change and demonstrable impacts for people and communities.

Researchers may find it challenging to isolate the changes which result from their research projects in emergency environments and monitoring the results of knowledge uptake is not a routine part of many research project or funding cycles. Supporting and tracking change should be the responsibility of all parties involved in generating and using evidence-based interventions; this especially pertains to the resources allocated by donors. Adequate time and funds are needed for uptake activities on research projects, and for monitoring and evaluation of these activities against specified outcomes, to ensure tangible change and demonstrable impacts for people and communities.

Despite the programme and policy changes reported, the study identified a general disconnect between country-level MHPSS practitioners and MHPSS intervention research. These findings have been highlighted previously (Tol et al., Reference Tol, Barbui, Galappatti, Silove, Betancourt, Souza, Golaz and van Ommeren2011a; Ventevogel, Reference Ventevogel, Morina and Nickerson2018). Decisions regarding MHPSS research topics appeared to remain more top-down than collaborative. The study noted a hierarchy of ideas that are supported by structural inequalities in research funding, and academic pressures placed on researchers. While this is not unique to the field of MHPSS and tends to be ubiquitous in humanitarian research (Leresche et al., Reference Leresche, Truppa, Martin, Marnicio, Rossi, Zmeter, Harb, Hamadeh and Leaning2020), it is imperative that effort is placed to ensure research is responsive to needs on the ground – in particular because this disconnection appears to be a major impediment to the uptake of research. Tol et al. (Reference Tol, Ager, Bizouerne, Byrant, Chammay, Colebunders, Gracía-Moreno, Hamdani, James, Jansen, Leku, Likindikoki, Panter-Brick, Pluess, Robinson, Ruttenberg, Savage, Welton-Mitchell, Hall, Shehadeh, Harmer and van Ommeren2020a, Reference Tol, Leku, Lakin, Carswell, Augustinavicius, Adaku, Au, Brown, Bryant, Garcia-Moreno, Musci, Ventevogel, White and van Ommeren2020b) highlight that the most studied MHPSS interventions are still not those that are widely utilised in humanitarian programming, and suggest that to minimise the disconnection, continued interactions amongst researchers and practitioners who are also decision makers are necessary.

Strong and inclusive researcher–practitioner collaboration can facilitate both higher quality and more relevant intervention research design, as well as support the interpretation and contextualisation of findings in ways that are most useful to the lived realities of practitioners and their programmes (Wright, Reference Wright2020; UNICEF, 2021). From inception onwards, engaging with local practitioners on the development of research empowers them to be active participants for the entirety of the process, and this, in turn, supports advances in programming.

Useful collaborations can include a range of stakeholders such as researchers, global- and country-level MHPSS practitioners, local and national governments, and community stakeholders. Strong collaborations were seen by those engaged in this consultation process to result in: (1) mutual learning for all parties involved, (2) improved quality of research through the insights of partners, (3) buy-in for the intervention from key stakeholders and (4) more direct avenues for programme and policy change.

Greater investment in collaborative research by funders, researchers, practitioners and their organisations, policy makers and people with lived experience would build the capacity and competencies of those involved, increase the likelihood of sustained buy-in from key stakeholders, and generate direct avenues to influence programming and policy change.

Limitations

The literature review was a scoping review rather than a systematic review, and in its balance of rigour and realism some relevant studies may not have been captured. By including only English language studies, relevant studies from non-Anglophone settings may have been omitted. Also, studies that focus on mental disorders were not included, but defining whether or not research is ‘disorder-focused’ is complex. Despite the robust rationale and rigorous selection process, another research team may have yielded different results. Using the search term ‘evaluation’ and ‘stress reduction’ v. (‘stress’ AND ‘reduction’) might have yielded different results.

Due to constraints from the COVID-19 pandemic, interviews were conducted remotely. As a number of potential key informants from national governments were engaged in their emergency response capacity, only two were interviewed. Fortunately, other key informants provided data on their interactions with national government actors, particularly senior practitioners and coordinators who work closely with this cohort. The same problem may have limited the number of respondents to the survey. The response to the survey was positive considering these circumstances; however, it was too small to disaggregate findings to a very granular level, e.g. comparing answers of community-based organisation staff with those working for international NGOs. The sample size was not large enough to provide statistically significant findings but was adequate for its intended purpose of triangulation with the qualitative interview data and considering the depth and detail of the form, the number of responses was judged to be satisfactory.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Leslie Jones and Ingrid Gercama who contributed to the literature search and quality review processes, and Tamara Roldán de Jong, Kelilah Liu and Sarah Meyer supported different stages of the project. We extend our sincere thanks to Elrha for providing funding and their high level of engagement with the project throughout, including constructive feedback on the framing of the work. We particularly thank all the interviewees and survey respondents for sharing their insights and giving their time so willingly.

Financial support

This work was supported by Elrha, who designed the scope of the review and published the full report.